Image A: Cemeteries contain a host of records that you can apply to your research.

Cemetery records offer a wealth of information for the genealogist and family historian. These burial records have been kept in some organized form since the mid-1800s, and church graveyards have kept track of their burials for much longer. These documents contain tidbits of vital information you won’t learn from other sources: a grave for a child who was never acknowledged, or an “extra” wife who was never spoken of. These little surprises can assist you in learning more about the deceased, their deaths, and their lives.

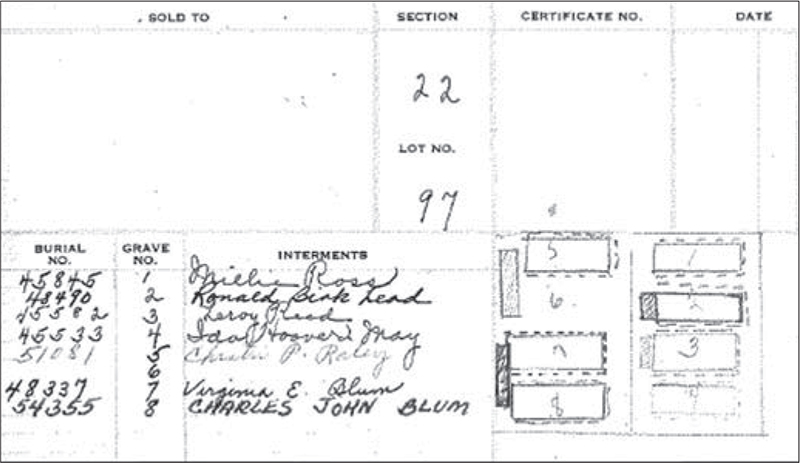

While you may only think about grave transcriptions (i.e., the carvings on grave markers), cemeteries contain several types of files that can reveal information about your departed ancestors, including sexton’s records, cemetery deeds, plot records, plat maps, and burial permits (image A).

Image A: Cemeteries contain a host of records that you can apply to your research.

Regardless of format and purpose, most cemetery documents contain the same or similar information: names, death dates, burial dates, plot locations, etc. But some forms may contain extra details—tidbits that can help you learn more about the deceased. Discovering the name of the informant who provided the final information for your deceased ancestor, and his relationship to the deceased, may introduce you to a new member of your family tree.

In this chapter, we’ll discuss each of the major kinds of cemetery records and what you can reasonably expect to find in each.

Also known as records of interment, the registry of burials, and “cemetery books,” sexton’s records are documents kept in the cemetery office. Today, all public cemeteries have superintendents and offices with certain hours of operation, or at least a phone number to call for assistance. Note these records are not necessarily written in a book and may be contained in ledgers or notebooks, on loose papers in filing cabinets, or even on index cards kept in boxes.

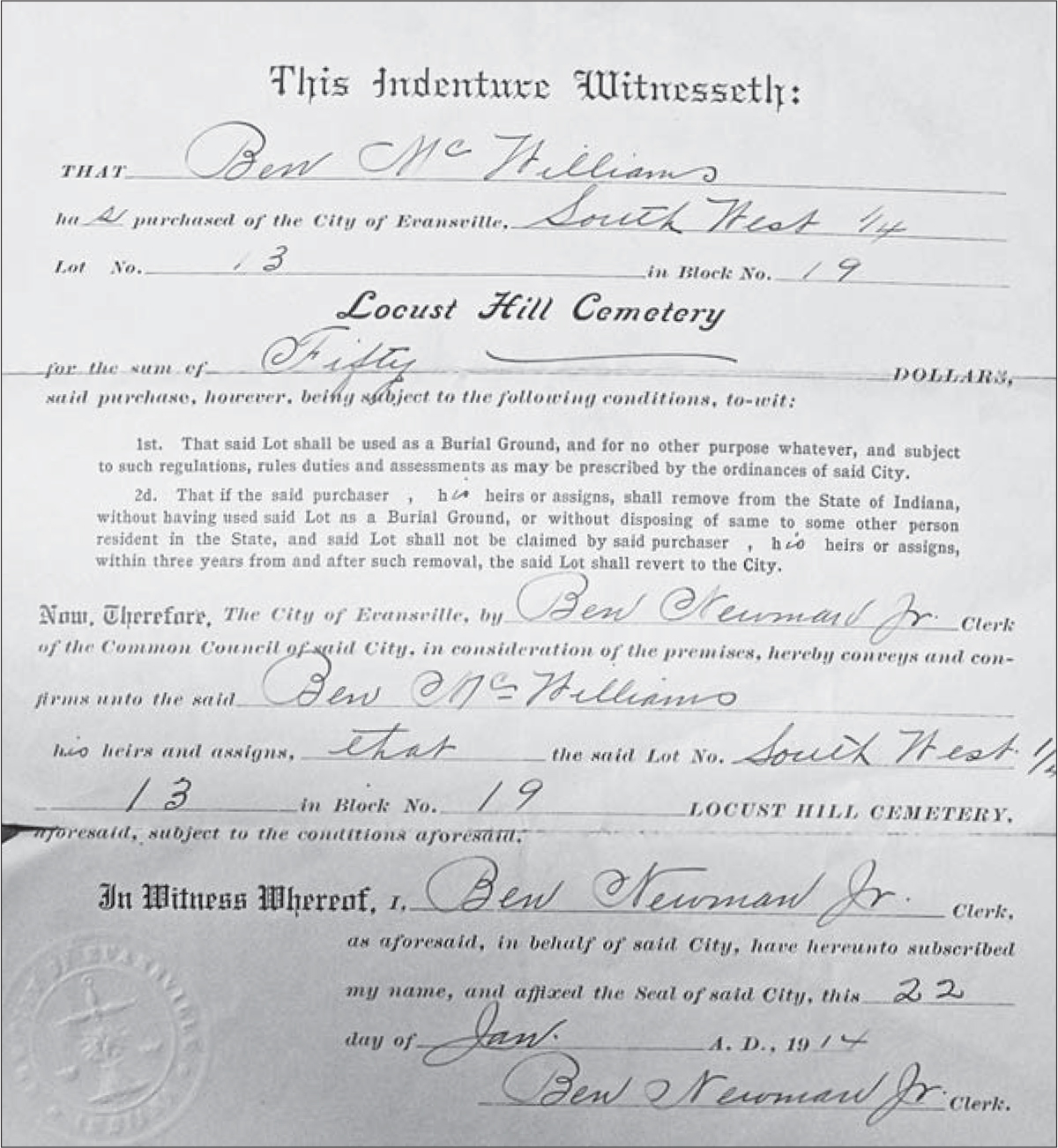

Older cemetery books (image B) contain three basic types of records: chronological records of burials, reports pertaining to where the graves are located, and cemetery deeds (see the next section). Burial records include the name of the person buried and the date of burial, but additional details (such as the name of the plot owner or how much was paid for the plot) will vary based on the sexton. Cemetery files may also include information on plots not sold, plus exact measurements of the lot.

Image B: Old cemetery books and ledgers contain a wealth of information.

Look for records online at DeathIndexes.com <www.deathindexes.com>, where you can search for obituaries, indexes, records, and cemeteries by state.

A cemetery deed, like any deed, is issued for the purchase of land, albeit a piece of real estate just large enough to bury the dead. The original deed is given to the purchaser, and the cemetery office keeps a copy for its files (image C). As with any other parcel of land, any transfer, sale, or inheritance involving this deed is recorded by the cemetery and the city or county recorder of deeds office where the cemetery is located. The deed includes the size and dimensions of the plot, name and address of the buyer and seller, amount paid, location of the burial lot (including section and plot number), and the name and address of the cemetery where the plot is located. By researching the cemetery deed, you might discover other plots that were also sold to the same buyer, dates of the purchase, how much was paid, if the plots were ever used, and who was buried there.

Image C: Cemetery deeds recorded the transfer of burial plots between people, giving you some information about your ancestors (often while they were still alive).

Before local governments became involved in overseeing cemeteries, no one put too much thought into diagramming or mapping out burial grounds. Those who died were usually buried in order of demise, grouped together as families, or buried wherever it was convenient. This can make it a challenge to locate graves in an older cemetery: There may be a record of who was buried where, but without an original plat map, the actual location of the grave may be lost to time. A visit to the cemetery’s office or a local genealogical society could provide you with the original plot records and/or plat maps.

Leave a Trail: Ask the cemetery superintendent if you can leave an index card in your ancestor’s file that has your name, address, e-mail address, phone number, and relationship to the deceased. This will allow others researching this person to connect with you, opening the door for future research collaboration.

Plot records contain information about the physical grave lot, usually the location or section, the plot or grave number, and a visual description of the site. You may also find the deed number, who the deed was issued to, when the plot was purchased, how much was paid, and if other plots were purchased at the same time. Plot records can be found in a “lot book.” These records will often include a description of the grave monument, including inscriptions and symbols.

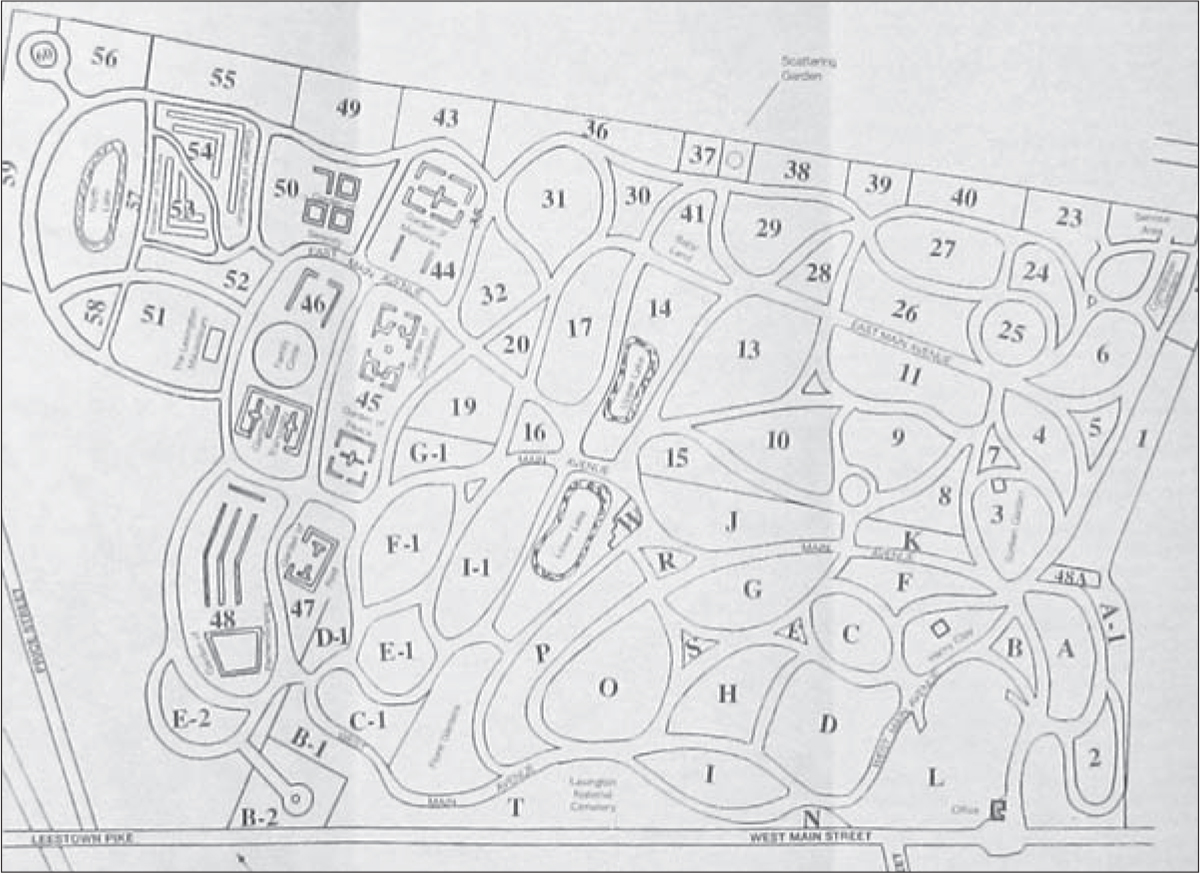

Plat maps (image D) are just that: maps that show the layout of all the graves in the cemetery. The plat book includes the burial section name and location number, the burial row number, and the grave or plot number. Additional details like who owns the grave and possible deed information may also be included. (These records can contain redundant information, but a change in one number or one letter can send you off on a new research adventure, so always pay attention and make sure the numbers correlate.)

Image D: Plat maps show you where individual tracts of land are within a cemetery.

Once you have found an ancestor’s grave on a plat map, pay attention to the names on the stones nearby. These could be family members, in-laws, close friends, or neighbors. Compare your findings to census records and see where these names fit into the scheme of things. Also, keep a list of the names to refer back to when you hit that inevitable brick wall.

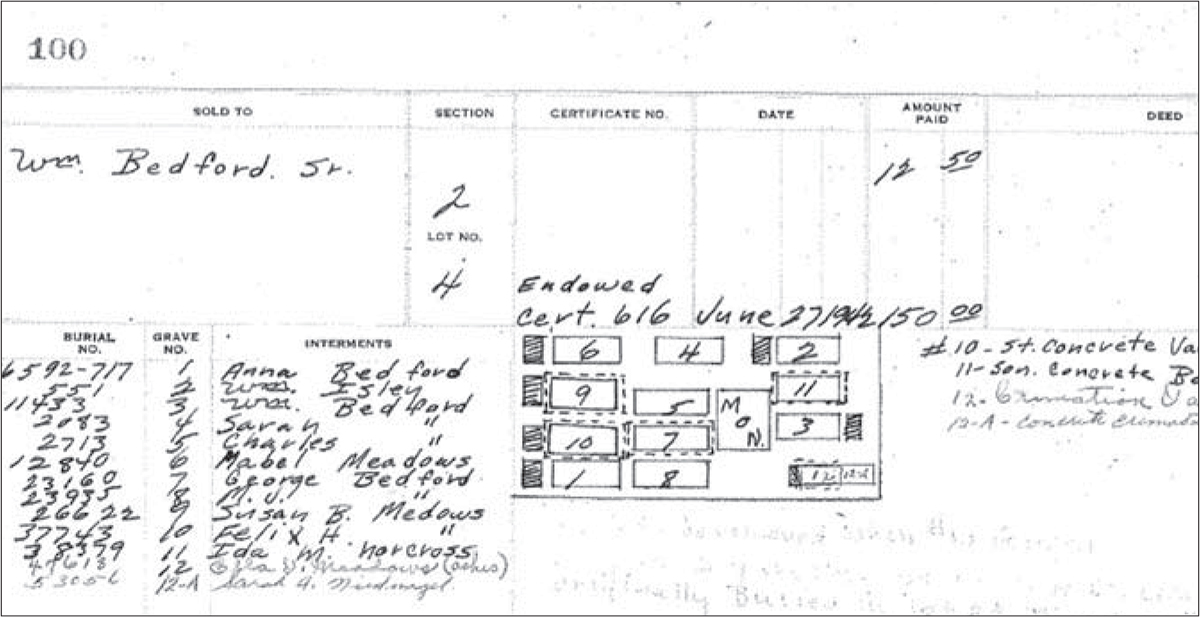

Let’s look at a couple examples to see what plot maps can tell us about our ancestors, and to see what doors they can open in our research. Plot maps are interesting in that they show the arrangement of burials in a family plot and how the cemetery ensured that everyone had adequate space. Notice the family plot in image E was sold to William Bedford, Sr., for $12.50. The location is in section two, lot number four. Notice, too, that burials 10 through 12A also reference what type of burial container was used: a concrete vault, concrete box, cremation vault, or concrete cremation vault. On June 27, 1942, someone paid $150 for “endowment care” for this plot, meaning regular maintenance and care of the plot (such as grass cutting and trimming, plant and tree care, road upkeep, and drainage of the cemetery).

Image E: This detailed plot record for the Bradford family plot provides valuable information, but also raises new research questions.

So what can we learn about the deceased? We see thirteen people were buried here, but not in a row as you might think. Anna Bedford was laid to rest first in the corner plot, followed by William Isley who was buried catty-cornered to Anna. William Bedford, the purchaser, was then buried next to the family monument (MON). As you read down the list, you can also see where the graves were placed and who was buried next to whom. Knowing the family genealogy can tell us which of these women was William’s wife and which were daughters or daughters-in-law. The name Meadows appears on four graves, and Norcross is listed on one. What was the relationship between these people, since all are interred in the Bedford family plot? The burial plot opens new lines of questions in your research.

In the next example (image F), Sarah Wiley purchased section 23 and lot number 11 for $60 on March 8, 1897, a spot large enough for four graves. Since Sarah bought the plot and her husband, Rudolph, is the first to be buried there, we can reasonably guess that her husband Rudolph’s death made buying a burial plot for the family necessary. The second to be laid to rest here was a woman named Madalina Stickmann. Could this be Sarah’s mother? Elizabeth Weley (notice the spelling change?) was the third to be buried in the plot, and she was placed next to Rudolph—possibly a daughter—followed by an Adam Stickmann, next to Madalina. But Sarah herself was not interred here.

Image F: Sarah Wiley purchased this four-grave burial lot, but she wasn’t buried in it. So who are the people who were buried there, and how are they related to her?

Know Your Vocab: The records we’ve discussed so far have been relatively straightforward, but the plot thickens as we move on to plat maps. The terms plot and plat are used interchangeably in many areas of the country, but there is a difference, and it pays to know what that distinction is. A plot is the actual grave lot, whereas plat refers to a geographical depiction such as a map.

Now we have unanswered questions. If Sarah were Rudolph’s wife, did she remarry? Was she buried with her next husband? Or was Elizabeth the wife, since she is resting next to Rudolph? This seems unlikely as, at that time, a woman would have been able to purchase a plot for her husband, but probably not a daughter. If she were married, her husband would have made the purchase for her. If she were too young to be married, a brother or uncle would have made the plot purchase. There are definitely plenty of questions that need answering, thanks to this plot listing.

One final example shows a communal plot (image G). Notice that most of the last names vary, and each person is buried in death order. This indicates these graves were sold independently, as needed. A listing to the side (not pictured) also tells us what type of container each person was buried in. Interestingly, lot number six was never filled; there is a double headstone—which indicates that Christina P. Roley’s spouse intended to be buried next to her but never was. Another clue to investigate in someone’s family tree.

Image G: Not all plots were owned by individuals. This one was a communal plot in which individuals were buried as needed. Note lot number 6 is empty.

Burial permits, known today as “disposition of remains” permits, are government documents allowing a body to be buried. They’re granted by a state’s local board of health or the town clerk in the town where the death occurred (even if the body is to be buried in another town). State and city health departments have been regulating burials since the beginning of the twentieth century.

A burial permit is issued to a funeral director or embalmer who is registered with the local board of health. The permit is then filled out by the funeral home handling the arrangements. A death certificate may be required to accompany the permit. Burial permits always include the name of the deceased and the date of death, but may also be issued as burial/removal permits that allow for the removal of the remains from the funeral home so they may be transported to the cemetery to be interred.

These permits can be as simple or as detailed as the department that issued them desired. A burial permit may also include the city in which the death occurred (not necessarily where the deceased had actually lived), the burial date, section and plot numbers in the cemetery, the name of the informant who provided information about the deceased, and that person’s relationship to the deceased. A burial permit will also sometimes list the manner of death, be it natural causes, accident, homicide, suicide, or undetermined circumstances (as well as if there is a pending investigation into the cause). The burial permit stays in the possession of the funeral director until after the burial has been completed.

Other records that are sometimes listed with a burial permit include burial transit permits, grave opening and closing orders, and information on disinterment of remains. In addition, our children and grandchildren will benefit from additional burial forms to use when researching more-recent burials: funeral order forms, on hold grave forms, and pinning forms.

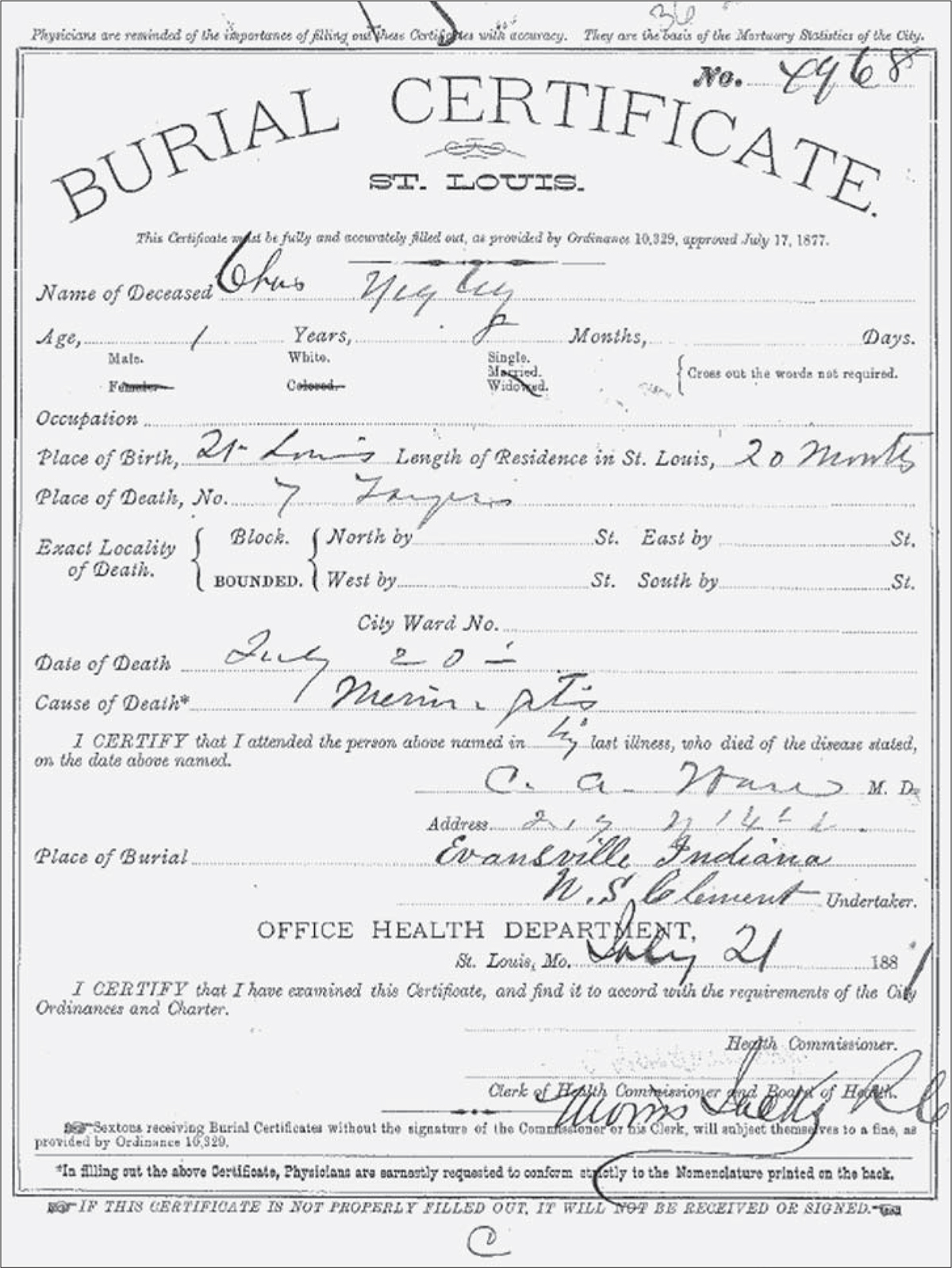

Let’s look at a couple of examples to learn what burial certificates can teach us. The St. Louis burial certificate for Charles Negley (image H) indicates he was one year, eight months old when he died. We also learn he was a white male who was born and died in St. Louis, although the exact place of death is hard to decipher. Charles died on July 20, 1881, of meningitis. Notice that he was buried in Evansville, Indiana, by an undertaker named W. S. Clement. Looking for files from Mr. Clement may help unravel why young Charles was buried more than 160 miles from his birthplace.

Image H: Burial certificates can provide tons of information about your ancestors: age, date and place of birth and death, cause of death, and more.

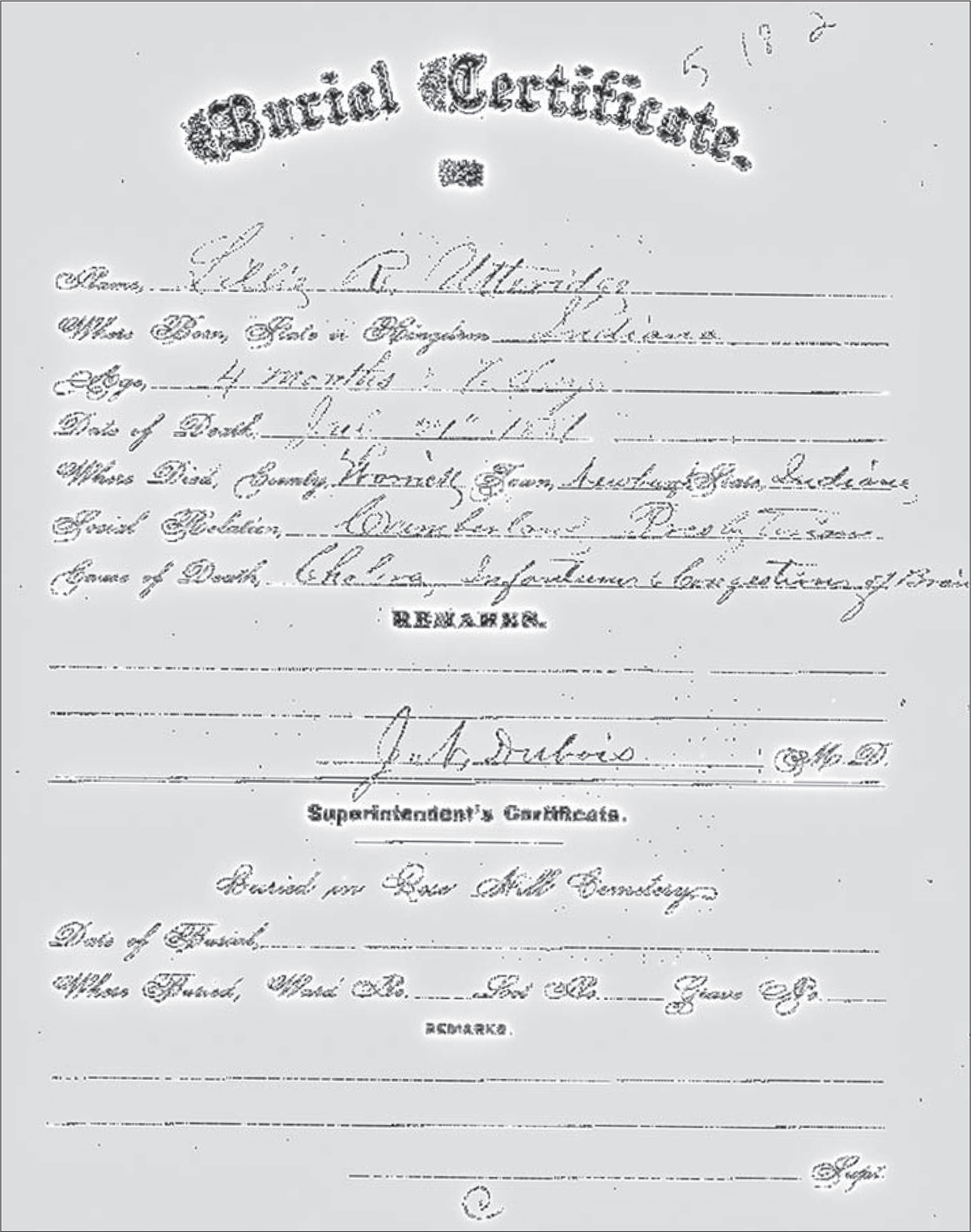

The burial certificate for Lizzie R. Utteridge (image I) was originally hard to read, but I can make out a little more by manipulating the image in iPhoto. I heighten the contrast to decipher more words, which lets me see Lizzie was born in Indiana and died at the age of four months on July 21, 1881, in Warrick County, Indiana. Her parent’s religion was Cumberland Presbyterian, which led me to research church records from that congregation. I found a website <www.cumberland.org/hfcpc> that hosts digitized Presbyterian records, and here I learned Lizzie’s cause of death was “cholera infantum” and “congestions of the brain.”

Image I: Not all records will be easy to read, but you can overcome this by scanning documents, then manipulating the images in photoediting programs. Consult other sources for even more insight.

By researching the two causes, we learn more about her death. Children in the United States were very susceptible to “cholera infantum,” a gastrointestinal illness that caused fever, vomiting, and diarrhea (Note: This is a separate, often deadly disease from cholera, a highly contagious disease that often manifested in outbreaks throughout the nineteenth century). At the time, the doctors believed this “summer complaint” (as it was sometimes called) to be caused by teething or hot weather, but it was more likely due to eating food that had gone bad.

“Congestion of the brain,” meanwhile, occurred when blood accumulated in the brain, possibly due to an infection. The brain would swell cutting off arterial flow to other parts, which could cause sudden death. Treatment at that time was to divert blood from the head by administering hot mustard footbaths, and by applying ice or cold water to the head (probably, in a cruel irony, the same water that could cause cholera).

At the end of the burial certificate, we see that Lizzie was buried in Rose Hill Cemetery in Evansville, Indiana, but the date of burial was not listed. While Rose Hill records are not plentiful, a walk in the cemetery may reveal not only Lizzie’s grave but also those of other family members, possibly names we didn’t know. And the search goes on …

Cemetery papers may also include funeral record (or funeral service) forms, created by the undertaker to glean pertinent information about the deceased’s burial.

In this example, the funeral record is for John Williams (image J) provides a lot of information to the family genealogist. From the record, we see that his daughter ordered the funeral after his death from tuberculosis. We also learn Mr. William was a retired merchant and a widower, and his parents were German and he was raised in the Catholic faith. The funeral service was to take place at 8 AM and would feature six pallbearers. The record even describes his casket: adorned with a cross and having six handles, along with a plate that read “Our Father.” He was laid to rest in a burial robe in St. Joseph’s Cemetery, and the record provides the lot number and section number given. Notice that seven carriages were hired to transport the funeral guests to the cemetery.

Image J: Funeral record forms were used as reference material for undertakers and can be valuable to researchers today.

Pay a Visit: If the cemetery you’re searching has no office, check with the folks at city hall. There’s usually a department that oversees local or county cemeteries, and a map of burials may be kept there. If not, visit the local genealogical or historical society and talk with area historians. A local library may also have books that pertain to burials in the region.

Today we have “grave opening and closing orders” that allow for the digging and filling in of the grave. These official orders granted permission for the cemetery to place the casket or remains into the grave, then seal it again. These records usually provide the name, gender, age, date and location of death, cause of death, burial place, and cemetery plot number, plus the undertaker’s name.

Death certificates may also be included in cemetery papers, depending on how detailed the superintendent was at the time. We’ll talk about death certificates in more detail in chapter 9, but for now we just want to note they may help us pinpoint an epidemic that ravaged the community at the time.

In image K, we see that Charles A. Plummer died on August 28, 1881. He was a white thirteen-year-old boy who was born in Indiana and lived in Evansville, Indiana, his entire life. Both of his parents came from New York State. Near the bottom of the form, we see that Charles died of typhoid fever, a bacterial disease that is contagious. It begins with an eruption of red spots on the chest and abdomen followed by a high fever, usually around 104 degrees, with abdominal pain, constipation, and headaches. By the third week, the infected person is emaciated and suffering from delusions and mental disturbances. If untreated, ten to thirty percent of those infected died of the disease, which was spread by eating or drinking food or water contaminated by the feces of an infected person. As the death certificate shows, Charles lasted four weeks after he contracted the disease.

Image K: Looking at death certificates for several people in a town can clue you into any major epidemics that may have affected the area.

From this death certificate, we can start an investigation to see if a rash of typhoid deaths were sweeping through Evansville, Indiana, during that period of time. Another Evansville-born preteen, fourteen-year-old Alleen Compton, contracted typhoid around the same time as Charles and died three days after Charles did. That information can lead us to search for other family members of these two boys to find out if others succumbed as well.

Many graves are marked with only the deceased’s name and death date, and some also include birth and marriage dates. But more detailed gravestone inscriptions can tell us a lot about the deceased: their lives, their families and their roles in them, their marital and economic statuses, their religions, their occupations, and information about any military service and any organizations and clubs they belonged to.

Inscriptions, or epitaphs, are short pieces of text or symbols inscribed on a tombstone that honor a deceased person, provide information about her, or act as a message (perhaps a warning) to the living. How someone is remembered can tell us a lot about who he was, his status in his family and community, and the period of time in which he lived. Many times the deceased selected her own epitaph. If not, a loved one or family member might do so.

As a result, epitaphs are as distinctive and varied as the people they honor. Many times epitaphs are heartfelt, informative, and enduring, while others are short and to the point. An epitaph can be descriptive, religious, thought-provoking, humorous, or an expression of grief or love. Some even contain poems, Bible verses, or inspirational quotes, giving some insight into the deceased’s values (image L). It all depends on the personality of the person who was buried there.

Image L: Some graves have more literary inscriptions, such as this one bearing the “Kiss of the Sun” poem.

But in addition to giving us clues about the deceased’s personality and values, epitaphs can indicate other key aspects of a person’s life. We’ll spend the rest of the chapter discussing how epitaphs can suggest different characteristics of a person’s life.

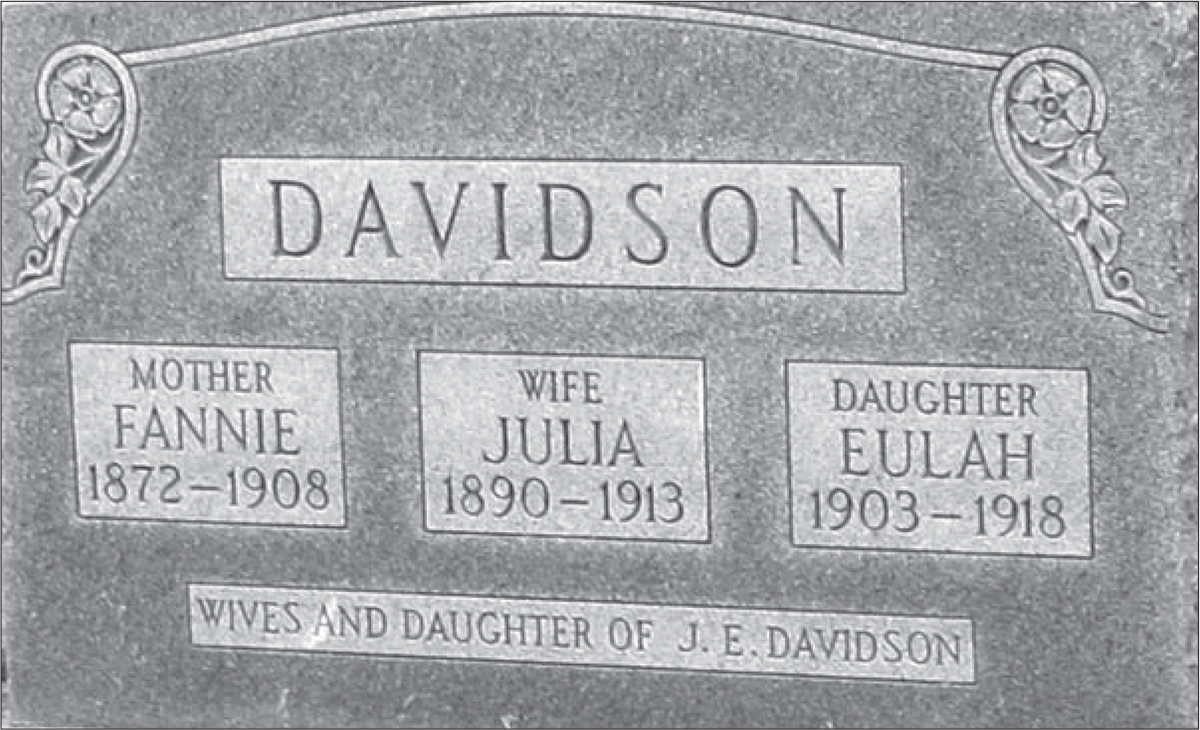

Relationships, even if only indicated by a single word (image M), can tell us who this person was and indicate further records to search: wife (the person was married), mother/father (the person had children), sister/brother (the person had siblings). Relationships also help us establish more ancestors in this line.

Image M: Titles and family relationships on tombstones can give you clues about what to research next.

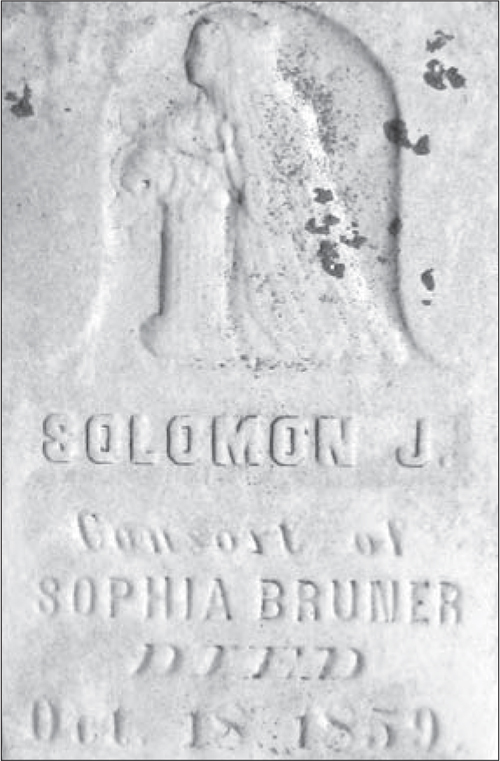

Wife and husband are easy enough to understand, but there are other marital terms you may not recognize that can be found on older stones. One such term is “consort,” which is used to describe the (non-ruling) spouse of a monarch—for example, Queen Elizabeth II’s consort is Prince Phillip. But when the word is found on a woman’s gravestone in the United States, it indicates that she was married and died before her husband. Similarly, the term is found on a man’s stone when he was married and passed away before his wife (image N).

Image N: “Consort” on a tombstone indicates that the deceased died before his spouse.

In a similar vein, the term “relict” describes a woman who was a widow at the time of her death. It may also indicate a widower, but it’s seldom seen on men’s graves of the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries—possibly because men remarried more often than women.

When you’re in the cemetery, always check the names on the graves near family members to see if there might be another spouse buried nearby (image O). Many times the husband will be buried between two wives, so check the dates and do some sleuthing to find out more.

Image O: People were sometimes buried with multiple spouses and family members.

A word or emblem carved on the stone or erected near the grave can indicate what faith your ancestor professed to. Crucifixes generally indicate Roman Catholicism (image P), for example, while plain crosses could refer to a wider variety of religious denominations.

Image P: Religious imagery on graves, such as a crucifix, can direct you to church records.

Keep in mind that cemeteries run by religious organizations were not always exclusive to adherents of that faith. For example, Grandma Matilda may be buried in a Baptist church’s cemetery, but that does not mean she really converted from Catholicism. In that case, you should check with both religious institutions when searching for her records.

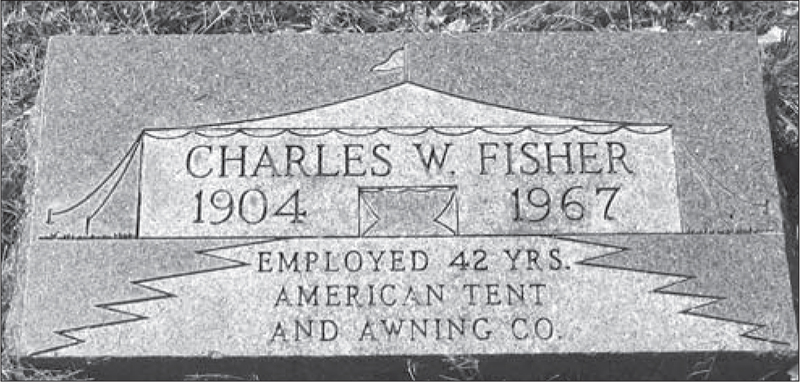

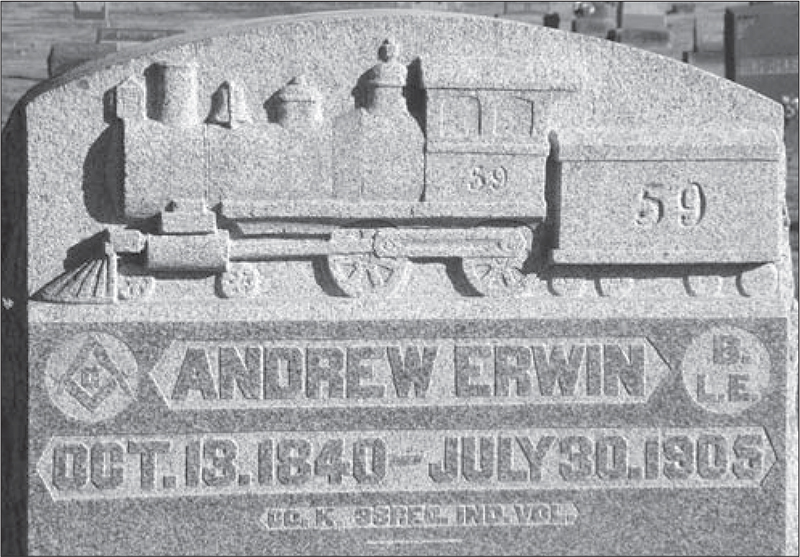

A job can be a status symbol, and many people were very proud of what they did for a living. Some were so proud they had it carved on their tombstones for the world to see, sometimes even including the company’s name (image Q). Others indicated their occupations with a symbol: a train carved on the stone of a railroad engineer (image R), or a cask for the local barrel maker.

Image Q: Some workers were so proud of the company they worked for that they mentioned it on their graves.

Image R: Andrew Erwin was a railroad engineer, and proud of it.

The size and shape of the stone/monument can also indicate the social status or economic position your ancestor held. A small concrete slab with painted letters tells a different story than a marble mausoleum, or a monument with the bust of the deceased carved on the front.

We are a nation proud of its military men and women, so military service is usually designated on a gravestone in some form. If the person died in a battle, the marker may list the unit he served in, rank held, and the war (image S). An emblem or plaque may also be located in front or on the back of the stone with more service details (image T).

Image S: Military graves are often marked by the symbol of the branch the deceased served in, or with a marker indicating the conflict(s) he served in.

Image T: Some gravestones provide more specific information about the deceased’s military service.

We have used symbols for thousands of years to convey our thoughts, feelings, and desires. Gravestones became more ornate in the mid-1800s during the Victorian era, and these carvings held special meanings and offer insight into a person’s life. This “silent language” was a way to honor a loved one and provide comfort to those left behind.

Several symbols can adorn a single stone, and the layers of meanings can tell the story, offering a glimpse into the deceased’s life and interests. Other symbols may be secret messages with the meanings known only to the family, the deceased, or the stonecarver. We’ll look at tombstone inscriptions and symbols in more detail in chapters 5 and 6.

• Seek out a variety of records at a cemetery (such as cemetery deeds, sexton’s records, and burial transit permits), not just tombstone inscriptions.

• Read and take note of everything that appears on a gravestone, as each symbol, word, and date has meaning. We’ll discuss tombstone inscriptions in more detail in chapters 5 and 6.

• Set defined goals for your trip to the cemetery. Outline who you’re searching for, the time period, who you will contact while you’re there, and why you are searching for this information.