§ 4 Export Ceramics in Philippine Societies: Historical and Ethnographic Perspectives

Introduction

Ethnohistory has become an increasingly viable approach for telling the story of significant parts of the planet, especially of those areas and peoples that have been marginalized in one sense or another by the onslaught of capitalism in the past several centuries. As a methodology, ethnohistory has been used to examine historical consciousness as constructed through mortuary rituals (Oakdale 2001), the telling of tales about important group events such as traumas (Salomon 2002), and even how individual societies weave narratives about their own geographic inclusiveness in the broader patterns of human contact (Carson 2002). Scholars who use material culture practices as an index of these conceptions have been particularly adept at advancing the agendas of ethnohistory, whether this has been from ethnographic, psychoanalytic, or Marxist points of view (Silverman 1990; Berger 1992: 63—84).1 Indeed, it may not be an exaggeration to say that anthropology and history have often mingled best in the realm of material culture complexes and their readings, or what Jean-Christophe Agnew blithely calls “History and Anthropology: Scenes from a Marriage” (Agnew 1990).

One global arena where this union has undoubtedly been effective has been Southeast Asia, as an inordinate number of first-rate ethnohistorical investigations have been conducted in this part of the world. Clifford Geertz and Edmund Leach may be the most noted practitioners of this boundary-crossing approach to scholarship in the region, but in reality they are only two of several important investigators who have used Southeast Asia to advance ethnohistorical programs in new and sophisticated ways.2 In the Philippines in particular ethnographers have used history to great effect in describing upland trade routes (Conklin 1980; but see also Rutherford [Chapter 3 in this volume] more generally on markets), the longue durée of headhunting (Rosaldo 1980), and the morphing of Christian ritual (Cannell 1999: 1–9). Not to be outdone, historians of the Philippines have also been sensitive to the possibilities of anthropology, whether this has been in the examination of early missionization and conversion (Rafael 1993) or maritime journeying in the Muslim seas of the southern archipelago (Warren 1981). The advice offered so many years ago by scholarly proponents of disciplinary fusion like Bernard Cohn (1987) seems to have been heeded, at least in research field locales such as the Philippines.

I wish to thank Harold Conklin, Emeritus Professor of Anthropology at Yale University, who read and critiqued an earlier version of this chapter. I am also grateful for audience comments at the Johnson Museum of Art at Cornell, where this chapter was presented as a talk on April 27, 2003.

The present chapter attempts to explore the relationship between export ceramics and societies in this Philippine context, both from historical and ethnographic points of view. Curling out in an arc from the Chinese mainland, Chinese porcelain and celadon can be found embedded in a variety of cultures: as heirlooms and burial jars in Philippine villages, adorning mosques and wats in Javanese and Thai religious buildings, and even as centerpieces on the tops of East African pillar tombs. Traveling the entire length of Asia’s maritime trade routes for more than a millennium, porcelain became part of the fabric of all of these societies in locally determined ways. Nowhere was this more true than in the Philippines. Incorporated into a bewildering array of rituals and local practice, they were used as bride-price items and as musical instruments; as a wealth-index and in magic; as child coffins and as wine jars. Few local peoples were unaffected by their export, and their legacy is still felt today in the more remote areas of the archipelago. In this chapter I will examine some of the histories and ethnographies of trade ceramics in the Philippines and how they have entered local societies in a variety of contexts. I contend that this narrative can be best understood through the observations of both historians and anthropologists, who together have left us a wealth of information on this important and understudied topic crucial to the story of Philippine societies.

Trade Ceramics: Histories of Movement

Before we begin the search for historical references as to how these interactions first started (and the scope of their diversity), it is useful to briefly sketch the circumstances around the earliest arrivals of these tradewares from abroad. The international maritime routes previously mentioned funneled all sorts of goods between highly centralized kingdoms like China and the many port-polities of Southeast Asia—not the least of which was porcelain.3 Porcelain entered this nexus from the T’ang (618–907) and Sung (960–1279) dynasties onward and became a major Chinese export industry by the Ming (1368–1644), usually finding its way into the monsoon countries in exchange for tropical forest products (Kamar Aga-Oglu 1961: 243; Laufer 1908: 248–251; Locsin and Locsin 1970: 4–5). In times of turmoil in China, as when the Sung Dynasty collapsed and was replaced with Mongol horsemen from the Central Asian steppes, other states were also able to enter this market. During the Mongol interregnum, Japan, Siam, and Vietnam flooded the region with their own wares at handsome levels of profit.

Aside from being a purely economic commodity, export ceramics were also a ritual one as well, as they symbolized (by the very nature of their manufacture) the differences between highly centralized societies and smaller, less multifunctional ones. Porcelain and celadons were prized (alongside gongs, bells, and high-fire beads) as nonperishable goods by indigenous Filipinos, items that were resistant to the monsoon climate and impossible to make at Filipino levels of technology.4 They therefore became important in local patterns of culture at a very early date. Solheim (1964: 376–381) has shown how existing “Malayo / Polynesian” pottery networks in Insular Southeast Asia started to give way to these material newcomers during the Sung Dynasty, while Beyer (1947: 211) has identified jar burials as a Philippine culture-trait—which nevertheless started to be performed with export wares around this time—in Batanes, Sulu, and Rizal. Tenazas (1984: 157) has also shown how entire settlements could be geographically situated around this trade, as with the site of Magsuhot in Negros Oriental, which seemed to serve as an expanded forest-products collection center geared toward exchange for trade ceramics.

By the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, high-fired Asian porcelain and celadons were being traded very far away from their initial production centers in China, Siam, and Vietnam. Chinese export wares in particular were being carried across global oceanic spaces—as far away as East Africa—in the early fifteenth century (Carswell 2000: 101, 126). From surviving shipwrecks we have an idea of the mechanics and dispersal patterns of many of these voyages, including the methods of shipment and quantities of cargo involved (Ridho and McKinnon 1979). Chinese data on the varieties, science, and motifs of these export wares is voluminous; researchers have documents and detritus that provide information on glazes, kilns, firing techniques, and artistic renderings of a startling amount of porcelain.5 The Philippines quickly became an important destination for a significant amount of this material, as the archipelago was relatively close to manufacturing centers in China and Vietnam and boasted a ready market for the products of this developing export trade.6

Historical Sources on Ceramics in Philippine Society

Although the earliest knowledge on the uses of ceramics in the Philippines comes to us through archaeological reports, it is with written documents that many of these practices become fleshed out for the very first time.7 Commentary written through hearsay—or more usually through eyewitnesses—describes local Philippine customs vis-à-vis ceramics as the pieces themselves were being used. In this first section of the chapter I present a cross-section of what these many uses were and how they reflect not only individual Philippine societies but their methods of innovation and change. Often the descriptions reveal as much about the viewers as they do about historical communities of Filipinos. The sources of these observations range from Chinese port attendants and dynastic records8 to Spanish friars and administrators, all of whom seemed to find these varied practices fascinating. As a whole, they give us a feeling for the many ways in which export ceramics had not only penetrated local societies but in turn helped shape them, both in the realms of utilitarian, everyday use and in the realm of ritual.

First and foremost on this historical list, interestingly enough, is an anthropological insight delivered by an external Chinese: Zhao Ru Gua (Chau Ju Kua), the harbormaster at Ch’uan-zhou port in the coastal province of Fujian. A keen listener and compiler of facts on the outside world, Zhao’s book Zhu Fan Zhi (written in 1225) is a combined ethnography / economic commentary on the nature of Sung Dynasty commerce. In his capacity as a regulator of the coastal city’s trade, Zhao was able to speak to many traders—both Chinese and foreign—who had eyewitness knowledge of the length of the maritime routes. It is therefore as a mix of reportage and tall tales that we can examine his section on the Philippine islanders, of which he says the following:

On each island lives a different tribe. Each tribe consists of about a thousand families. As soon as a foreign ship comes in sight the natives approach it to barter. They live in rush huts.... In the most remote valleys there lives another tribe called Hai-tan (the Negrito). They are of small stature, have brown eyes and frizzled hair, and their teeth shine between their lips. They live high up on the tops of trees, where they dwell in families of 3 to 5 individuals. Crawling through the thickets of the forest, they shoot from ambush at passersby, wherefore they are most dreaded, but if a porcelain bowl is thrown towards them they rush on to it, shouting with joy, and escape with their spoil. (Chau Ju Kua 1966: 161)

What is immediately interesting about this account is the dichotomy set up between larger (presumably coastal) groups, numbering up to a thousand families, and forest-dwellers, who live in much smaller units of five or less. The former, Zhao says, approach Chinese ships calmly and regularly when they want to trade, while the latter lurk just out of reach, trying by any means possible to get their hands on the jars. This is nascent ethnography, to be sure: two populations are described, each with a different ecological niche and size, but what further classifies them as separate are their attitudes toward ceramics. Solheim (1965: 265) has argued that one of the primary linkages between interior and exterior peoples in the Philippines was the “status-quest” for jars, but this Chinese account speaks to even larger patterns of Southeast Asian exchange, such as the overarching, modular thesis posited by Bronson in Karl Hutterer’s 1977 volume (p. 39). Zhao Ru Gua’s “ethnography” seems to be a direct corroboration of their upland / lowland hypothesis, which asserts a division of peoples in a pan–Southeast Asian context based on the remoteness of their geography. The unifying (and separating) bond in this instance was the entrance of the export wares, bringing groups together for trade and keeping them separate based on their frequency of dealing with such high-status imports.

A second important insight delivered by the historical sources concerns the transvaluation of external Philippine diplomacy. By the early sixteenth century porcelain not only appears in Chinese and Spanish writings as a highly valued item coming into the archipelago, but also as a stock tributary gift from Filipinos paying obeisance to external powers. In the Mingshih (Records of the Ming Dynasty), notices recorded that a power struggle was erupting in the seas of the “Southern Ocean” (or Nanyang) in the early 1400s: Maguindanao and Sulu were on the losing end of the contest at that point in time and were bringing gifts of semi-vassalage—including Chinese porcelain—to their nominal overlords at Brunei (Roxas-Lim 1987: 44). A century and a half later, a Spanish notary, Hernando Riquel, wrote to the Crown that two ships were embarking for Spain filled with the tribute of Philippine rulers and that among the jewels and items of gold were porcelains, “many rich and large jars” (Riquel 1903: 249), as a token of local respect for the king. Finally, by the late eighteenth century Taosug datus (princes) residents in the lowland reaches of northern Borneo were also bringing jars to local Kenyah chiefs, partly in exchange for forest produce (which was then shipped out into the world market via Sulu) and partly as delicate political protection in a region renowned for its headhunting (Warren 1981: 76). All of these cases are interesting as they reveal a change in the nature of Philippine embassies over time; at one point only able to provide items of the environment to show their respects, Filipinos had now entered porcelain into the “language of obeisance” in their external relations, rerouting them into other parts of the region.

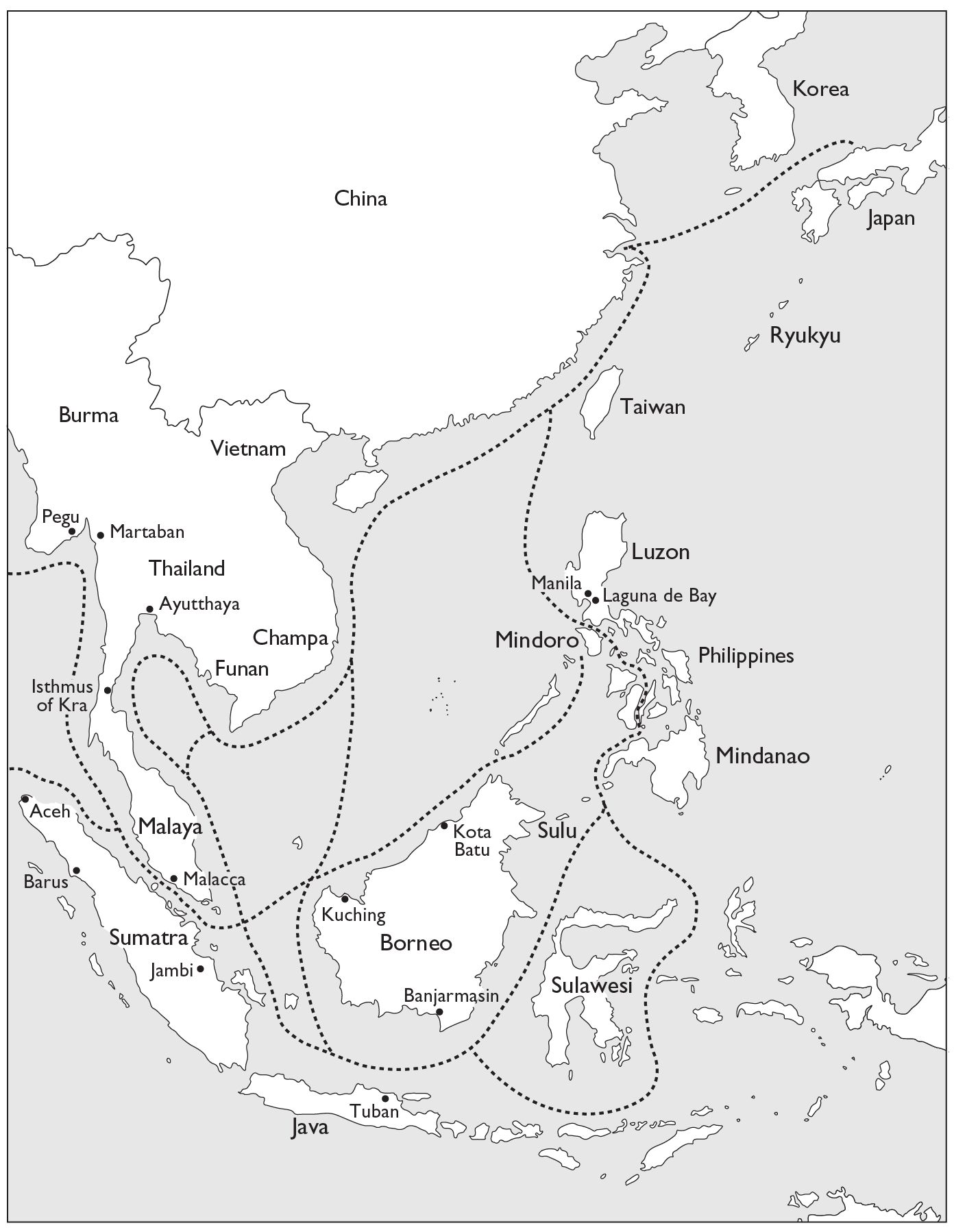

MAP 4.1: Map of the Philippines and attendant ceramic routes.

Yet it would be wrong to assume that these export ceramics only served such ceremonial functions. The literature of the earliest Spanish contacts also depicts these tradewares as entering the mainstream of Philippine societies, reaching a range of Filipinos in very utilitarian ways. Pigafetta was wined and dined in Leyte by a group of local villagers, who presented him with two porcelain dishes full of rice and pork (Pigafetta 1903: 119). Later (in Cebu) he chronicled another description of local hospitality, which included a gourmand chief who received his party favorably:

When we reached the city we found the king in his palace surrounded by many people. He was seated on a palm mat on the ground, with only a cotton cloth before his privies, and a scarf embroidered with a needle about his head, a necklace of great value hanging from his neck, and two large gold earrings fastened in his ears set round with precious gems. He was fat and short, and tattooed with fire in various designs. From another mat on the ground he was eating turtle eggs which were in two porcelain dishes, and he had four jars full of palm wine in front of him covered with sweet-smelling herbs and arranged with four small reeds in each jar by means of which he drank. (Pigafetta 1903: 149)

Ceramics seem to have been preferred not only because of their exotic provenance but also based on other reasons: they were more hygienic than coconut or wooden vessels, and they were also easier to clean and did not affect the taste of food (Janse 1944: 37; Hobson 1962: 92; Honey 1954: 95–96). By this time they were also making inroads into all sorts of local activities and industries: as liquid and dry-foods containers, in the processing of foods such as preservation and pickling, and in manufacturing processes like tanning and the extraction of dyes (Roxas-Lim 1987: 9). The majority of these pieces were the sturdy stoneware jars known as martabans or tempayans, not the blue-and-whites or the pale green celadons currently seen in museums. These latter types were more often reserved for ritual functions, of which early sources tell us a great deal.

Pigafetta’s notices of communal wine drinking from special jars in Cebu is not the only example of ceramics making their way into local Philippine culture. In fact, from the earliest Spanish explorers onward, a long list of such observations begins to enter the literature, as Europeans came face to face with ritual uses of porcelain on a wide geographic scale. Pigafetta also recounted seeing small tradewares being used as receptacles for the burning of incenses (benzoin, storrh, and myrrh) in Cebu funerals, while other pieces were used as betel-nut containers to house the areca before ceremonial consumption (Roxas-Lim 1966: 230). In 1601 Father Chirino saw jars being erected on promontories in the western extremities of Panay, offered to the spirits as supplications for safe voyages (Chirino 1903: 267), while four years later he saw them utilized as “charm-containers” in Bohol, the contents of which determined the precise times for sacrifices to cure local sickness (1903: 81). By mid-century Father Aduarte was contributing to these accounts, noting with astonishment that Filipinos placed valuable jars in places of “ritual power” alongside gold and gems, none of which was ever stolen by inhabitants of the region (either inside or outside of the village). The local inhabitants were too afraid of the sanctity of the location to ever attempt such a taboo, but when the jars were brought back to the village, they had evidently accrued the power of the place, for people then sought to eat off of them (Aduarte 1903b: 289). This last practice seems analogous to practices still undertaken in Northern Luzon, where some indigenes of Mountain Province continue to bury jars of rice wine in ritually powerful places, the wine then only being drunk (from these same export porcelains) on ceremonial occasions (Solheim 1965: 256).

Yet both of these Fathers (Aduarte and Chirino) also serve as conduits of a more debatable kind of information on ceramics in early Philippine society, namely of their destruction under the pressure of Spanish Christianization. The conflict between missionization and the survival of indigenous ritual was played out in many shapes and forms, and ritual paraphernalia—including porcelain and other “magically-invested items”—were a very material part of this battleground. In some cases, as in Pangasinan in 1640, the destruction of tradewares used in local rites seems to have been a voluntary act of conversion: Aduarte mentions that several local chiefs willingly brought their jars of quila libations to one resident Father, who then destroyed the contents with the help (and consent) of the local villagers (Aduarte 1903b: 243). Yet this cooperative approach seems to have been the exception rather than the rule. Chirino gives a long narration of a Father Sanchez in Bohol, who came to the problem with a different line of action: pouncing on the local stores of ceramics and magical horns, he trod and spat on the items—without the help of his native assistants, who were too afraid to join him—and then threw the entire cache into the river (Chirino 1903: 81–82). Another Father (Pedro de la Bastida), this time back in Pangasinan, “upset everything and broke the dishes and bowls and other vessels which (the villagers) used in their rites,” finally ending his rampage by burning the robes of the priestesses and the huts in which they lived. Aduarte was incredulous at his survival as “many were thus aroused to Christ and undeceived, but others, and not a few, were angry so that it was a wonder he was not slain” (Aduarte 1903a: 145). What is important for our purposes is less the heavy-handedness or insensitivity of conversion in these narratives, but more the ritual place ceramics occupied in the clash of different cultures: one aggressive and proselytizing, demanding faithful converts, the other an exposed, almost cornered one, simply trying to survive.

Yet there is one Philippine practice concerning tradewares that stands out strongest in the historical sources, mentioned more frequently and with greater interest than any other ritual: the custom of jar burial. Beyer (1947: 115) reports that evidence of this practice has been found in Northeastern Luzon, Southern Tayabas, Sorsogon, Samar, Mindanao, Marinduque, Mindoro, and Palawan, though further excavations have been conducted since the time of his writing.9 The so-called Boxer Codex of 1590 is perhaps the first in-depth notice of such rituals, in which bones were described as being placed in jars in the midst of Luzon houses, and jarlets and plates were interred with corpses in the lower Cagayan (Quirino and Garcia 1958: 432). Again, Father Aduarte transmits the feeling of these discoveries most forcefully, as he narrates in this episode from his shipwreck in the “Babuyones”:

Now that our supplies were cut off, we were obliged, since food is necessary, to take it by force wherever we could find it, since they (the local inhabitants) would not sell it willingly; so for several mornings a troop of our Indians went out under escort of our soldiers, gathered what they could from the fields, and brought it back as food for all. At one time when they were engaged in this way they thought they had discovered a great treasure; for they found some porcelain jars of moderate size covered by others of similar size, and inside they found some dead bodies dried, and nothing else. (Aduarte 1903a: 115)

The use of the term treasure here is instructive, as evidently many Spaniards started to plunder these sites after learning of their potential value. Janse (1944: 41) also records burials in Batangas where ceramics were placed over the thorax, mouth, and feet of the dead, indicating a definite method to placement of the objects, while Fox discovered in his own excavations near the same site (Catalagan) that the largest number of porcelains were actually associated with children (Fox 1959: 345). The larger picture presented by all of these records—archaeological and historical—is one of a pervasive incidence of the custom. Ceramics were in use throughout the archipelago as objects essential to the afterlife.

Ethnography on Ceramics in Philippine Society

Contemporary ethnologists in the Philippines have been interested in trade ceramics, the culture complexes surrounding them, and general issues of material culture and movement for quite some time. These studies have focused on porcelain in Mindoro (Lopez 1976: 4–5), ceramic distribution networks in Kalinga (Stark 1994: 169–198), and pottery wealth indices in Mountain province, Northern Luzon (Trostel 1994: 209–223), among many other issues.10 It was only in the beginning of the twentieth century that serious empirical studies about the nature of Philippine society began to be written from anthropological perspectives. The local uses and traditions involving export porcelains fit into this evolving literature, as researchers catalogued ceremonies and practices with new attention to detail. Ethnographic theory also started to be applied toward these relationships, as explanations were sought for the mechanics of certain communal rites. The study of ceramics in Philippine culture continued to be undertaken along historical lines, but with a much greater emphasis now on how Filipinos were still using these pieces and how these customs had changed.

One practice that did not substantially change in the years connecting historical and ethnographic inquiry was the practice of value-creation involving ceramics as an index of social hierarchy. It is no accident that a 1574 report of the Spanish Crown spoke of Chinese junks bringing earthenwares to trade with commoners and “silks and fine porcelains” as barter goods for chiefs; a distinction was already being made by this date, one which was perpetuated by the new owners of such objects (Riquel 1903: 245). In the early twentieth century, Christie (1909: 56) found solid evidence of a continuation of these value-perceptions among the Subanuns of Zamboanga, who competed within the peninsula to attain as many large drinking vessels (tempayan) as physically possible. Solheim (1965: 258) even points out that these tendencies still exist to the present day in many parts of the Philippines, as families engaged in important rites of passage (e.g., weddings, christenings, and circumcisions) still display their feasts in the best porcelains they can afford before the food is eaten by the guests. In this respect, the hierarchy-producing capacity of pottery as an index of wealth and prestige appears to be similar to the heirlooms shown by Wong (1978: 92) to be part of seventeenth-century St. Ana society: plates and saucers being bought for 1,500 guan, while a horse cost a mere 800.11

The survival of porcelains in a wide range of magical and religious practices is also confirmed by twentieth-century ethnographic literature. Cole (1912: 12–13) in particular cataloged a tremendous variety of these uses, perhaps most impressively among the Tinguian of Abra. The Tinguian had incorporated jars into a fantastic web of stories and oral literature by 1912: informants spoke of jars that could talk and went on solo journeys, and one was even reported to have gotten married and begotten children with a female piece in Ilocos Norte. A second folktale recounted fields full of jars trembling with their tongues hanging out, demanding to be fed betel on pain of devouring the local villagers. Yet one does not merely have to enter the realm of local mythologies to see these relationships acted out: spirit-mediums in the same area never sold their porcelains during their own lifetimes, opting to hand them down instead to the inheritors of their ritual powers, local female acolytes. In Rizal and Pampanga, tradewares were still considered to reveal the presence of poisons (through discoloration of the plate) as late as the 1960s (Roxas-Lim 1966: 229), while churches in Northern Luzon used them as receptacles for holy water, sometimes cementing them into the structure of the religious building itself (Solheim 1965: 261). A final, revealing example of the continuing belief in the efficacy of such pieces comes back to the funerary complex and its hold on Philippine life—this time in Sagada, Mountain Province. While excavating at the site, Solheim (1959: 129) heard stories of a local couple asking the resident priest if they could bury their dead child in a jar and still hope to have the baby receive Christian grace. The priest (who was known to be a moderate man) felt that this would be stretching doctrine a bit too far and therefore dissented; the child was buried in a coffin, and the matter was thought closed. Only a short time after, however, the parents of the child disinterred the corpse, cut up the body, and transferred it to a very old jar, which they then put back into the ground. Occurring right before World War II, the incident shows the continuing power of these local beliefs up until quite recent times—a hedging of bets, as it were, between Catholicism and far older customs still current in the countryside.12

Ceramics have also survived as an element of another age-old Philippine rite—the arrangement of bride-price. As late as the early twentieth century, the custom was very much alive in the interior regions of Mindanao, Palawan, and Luzon, with jars being part of exchanges at the unions of families or as partial or full payment for the acquisition of a wife. Among the Subanun of Sindangan these transactions developed into a complicated dialectic: the prospective bridegroom had to possess, among other things, a certain amount of tradewares—which were then belittled by the family of the girl, who demanded more—and so on and so on, the haggling sometimes lasting for days (Christie 1909: 114). In other areas the number of jars for bride-price were reckoned in equivalencies of carabao, with renowned pieces equaling certain numbers of the animals and less important types a corresponding amount (Locsin and Locsin 1970: 258). Tinguian youths even had to haul large Chinese jars on their backs to the houses of their new fathers-in-law, whom they were never again able to address by name once the gifts had been presented (Cole 1912: 14). The place of tradewares in these rituals of course managed (as a corollary) to also penetrate local mythology. The same Abra folktales that recounted jars marrying and flying also reinscribed bride-price customs in the collective memory, telling of balaua spirit-houses filled nine times over with porcelains, all as gifts to a beautiful maiden’s family (1912: 13).

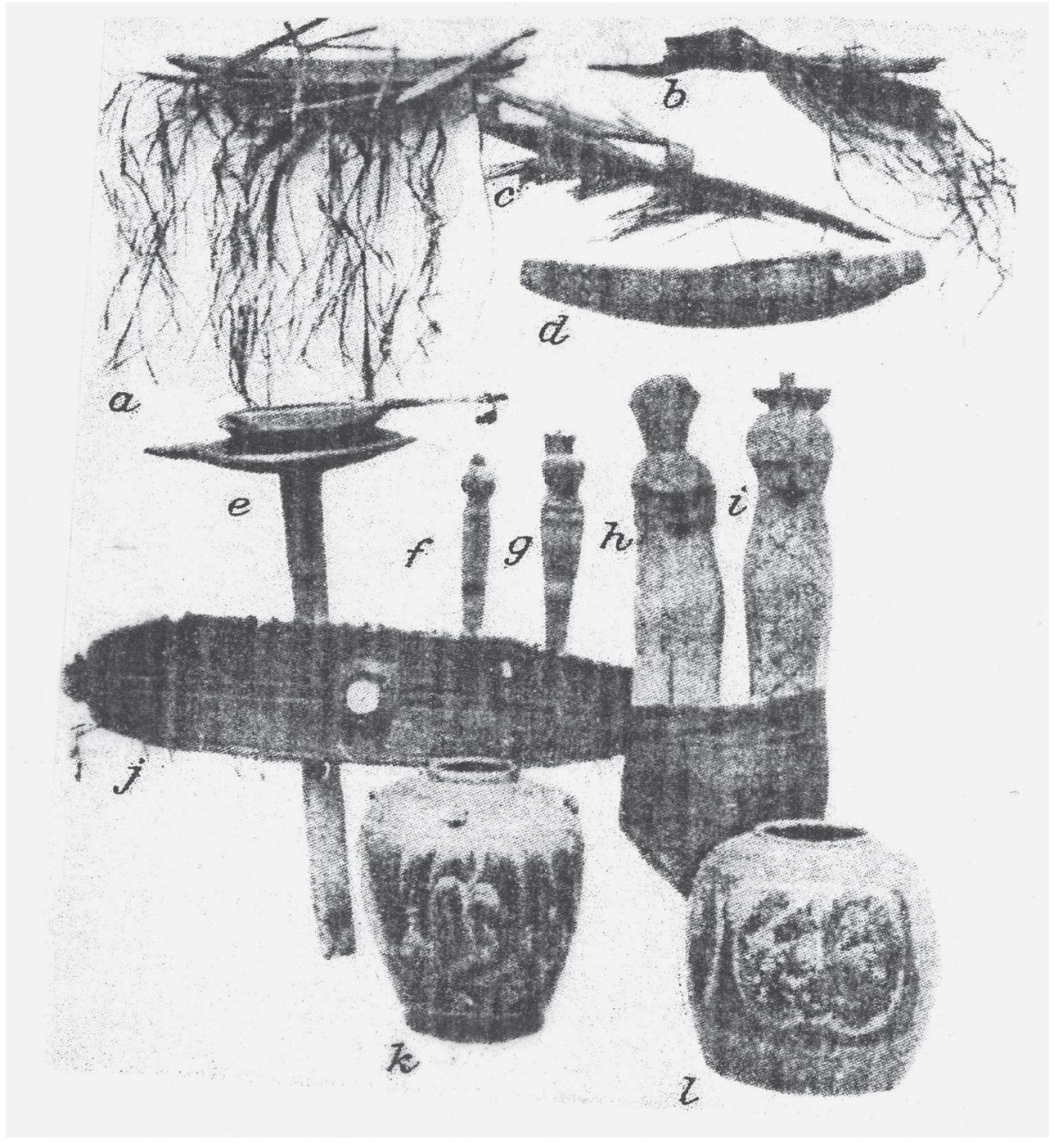

FIGURE 4.1: Manobo ceramics. Source: Garvan (1929). Reprinted with permission from the National Academy of Sciences, Washington, D.C.

Not all of these aspects of ceramics entering Philippine societies were so peaceful, however. The gradual extension of first Spanish and then American authority to remote areas caused certain changes, one of which had important ramifications for the position of these tradewares. By the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, headhunting was starting to be seriously suppressed in the more remote parts of the archipelago, as the colonial administrations tried to bring local peoples into what they called the “orbit of civilization” (Rosaldo 1980: 31 passim). This disrupted local patterns of equilibrium in a fundamental manner, as often one tribe would take heads from another in a raid and then make amends—“pay the balance”—by substituting the heads of their own members with an equal number of jars. Both heads and jars were religiously invested, powerful items; from the scattered evidence that we have, the exchange was seen to be an equitable one by both sides, though it may seem somewhat lopsided to Western sensibilities.13 Fay-Cooper Cole went on one of these conciliation missions with an Apayao group to a neighboring village and witnessed the distribution of eleven Chinese jars as compensation for a recent attack (Cole 1912: 15). Yet as headhunting was slowly phased out of the rhythms of these rural areas, items like gongs and charms—and especially esteemed porcelains—became correspondingly more important. As indicators of status and prestige between rival villages, export ceramics took on much of the slack created by the void of disappearing heads, which were increasingly rare goods as American influence expanded. In this case the intersections between political history, material culture, and rural ritual become immediately apparent; each acted on the others to mutate systems of exchange, with ceramics in a central place to help chart these metamorphoses.

Another fascinating incorporation of porcelains that stands out in the ethnographic literature involves their use as musical instruments. Ethno-musicologists have noticed this widespread culture-trait from Northern Luzon (among the Kalinga, Igorot, and Ifugao) to Palawan (among the Tinguian and Tagbanuwa), with the ceramics generally being utilized as summoners of spirits (Wilson 1988: 38). Robert Fox has given eyewitness descriptions of this practice among the Tagbanuwa, in which a spirit-medium (usually female) will place betel and husked rice into an old bowl or plate, lift it over her head while tapping the container five to seven times, and then chant for the ancestors to come partake in the offering (Fox 1959: 364). It was essential, Fox says, that the receptacle be of true porcelain: the spirits could easily hear the difference in the clarity of the ring, so precious fifteenth-century vessels were the preferred item of choice. In his Tagbanuwa: Religion and Society (1982: plate V) Fox publishes a photograph of the usual proffered arrangement, which shows a forest platform of bamboo resplendent with Chinese bowls, betel, and sacrificial chicks. Fay-Cooper Cole also gave descriptions of these ceremonies, chronicling women sitting on special “spirit-mats” and covering their faces with their hands, shaking violently, and then calling the spirits by striking the ceramics with strings of seashells (1912: 15). The invocations were apparently successful: the ringing sound attracted the ancestors, the women were soon chanting and rocking, and the spirits spoke to the assembled villagers, all through the medium of the priestess.

Yet how did Filipinos decide which porcelains were to be used for which ceremonies and why certain pieces were more valuable or desirable than others? These locally constructed indices are a vital part of the story, and fieldwork conducted during this century reveals that the choices were made along complicated lines. Solheim (1965: 266) noticed that different groups in Mountain Province seemed to prefer different types of jars, usually based on the texture or color of the outer glaze—not the provenance of the pieces (i.e., very valuable fifteenth-century Annamese wares could equal much less valuable eighteenth-century Swatow Chinese ones). Other authors also commented on the fact that local groups made no distinction between such histories, choosing instead to focus on the physicality of the piece (Fox 1959: 364–365; Cole 1912: 15; Evangelista quoted in Roxas-Lim 1966: 235). What has apparently emerged is completely indigenous, locally specific gradients for selecting such preferences: decisions made by Filipinos about foreign wares as to their new value in Philippine society. Surface attributes have often been at the forefront of these considerations, with the hardness or relative fragility of a piece, its smoothness or shiny texture, or the color of the glaze deciding its worth. But function has played a large part in these decisions as well, with ceramics often being integrated into uses that best fit their physical attributes: jarlets for oils and perfumes, spouted teapots for pouring, and large martabans for communal wine-drinking.14 In cases in which a village possessed enough different pieces, these varying delineations along ritual and utilitarian lines could be made easily. Ceramic-poor peoples, however, more often had to combine functions into single specimens: for example, a plate serving as a percussion instrument in a sickness exorcism might also be utilized in the payment of bride-price (Roxas-Lim 1966: 233). Many of these pieces were even given proper names, based along these same lines of function and physical appearance.

A final aspect of the incorporation of trade porcelains that needs to be mentioned briefly concerns the diffusion of stylistic attributes. Many ethnographers have commented on the ways iconographies travel along trade routes, with a symbol in the country of commodity manufacture metamorphosing into a different meaning after reaching its destination.15 This definitely seems to have taken place in the Philippines, with ceramics contributing substantially toward enriching the traditions of local artistic systems. The geometric patterns surrounding the lips and bases of Chinese jars have reappeared on Philippine textiles and embroidery, while also showing up on decorative carvings and in tattoos. Perhaps the most famous example of this transfusion, however, has been a zoomorphic one—the Chinese dragon of Ming Dynasty “dragon jars” bearing remarkable similarities to indigenous renditions of crocodiles. Yet a further aspect of this stylistic movement has been more technologically oriented than artistic, as Filipinos have also constructed a vast array of paraphernalia to complement the appearance of these ceramics. There are many examples of this category of material culture (i.e., mesh jar-holders and dish-protection amulets), but perhaps the best is the simple plank preserved in Yale University’s Peabody Museum, which was carved and installed to suspend heirloom pieces that a host’s guests could then see (Peabody Collection #7025, Item #229650). Projected social status here rode the combined artistic/ technological wake of innovation, as Filipinos found new ways to exclaim the importance of their jars—and thus of themselves—to their neighbors and acquaintances. Without the importation of such tradewares, the stimulus for such a display would no doubt have been different—and most likely channeled into some other form.

Conclusions

The flood of porcelain that started to inundate the Philippine archipelago from A.D. 1000 onward caused a variety of ripple effects on local cultures and societies. Archaeological data posits the entrance of such goods into a wide spectrum of ritual, with the first and most notable of these practices concerning the variable cults of the dead. Tradewares played an increasingly important part in these rites, as jar and secondary burials entered the cultural lives of generations of Filipinos. With the start of written notices about the Philippines by Chinese and early Spanish explorers, other customs involving porcelains were chronicled for the first time, indicating ceramic-use in an expanded array of ceremonial functions. Given in tribute and utilized in everyday life, they were also a measure of social hierarchy and used in local ritual. The advent of Christianity and the missionization process endangered these practices but never fully destroyed them. Some Filipinos bowed to these pressures as a sign of their conversion, while others continued to revere the heirlooms handed down by their forefathers. By the time ethnographers began systematically cataloguing these rituals in the early twentieth century, ceramics had spread into almost every corner of the islands, from Batanes to Sulu and Palawan to Mindanao. More than perhaps any other material culture object imported from abroad, they were grafted into local systems on an extremely diverse scale, holding their place in the minds of generations of Filipinos.

Studying the histories and cultural uses of export ceramics in the Philippine context allows us to see them as markers of a particularly complicated social terrain. In Janet Hoskins’s elegant terminology, trade ceramics have been “biographical objects,” or “things that tell the stories of people’s lives” (Hoskins 1998).16 More than acting as simply indices of social value or of the relationships between various human actors (Dant 1999: 40–59), these tradewares literally allow researchers to see the nuanced spaces where sociality and history meet in discrete, bounded societies. Though some theorists of material culture have used the data collected about such objects to make narrow, scientific observations about culture and society (Tite 1996: 231–260; Corn 1996: 35–54), there are signs that material culture is increasingly being used to say larger things about broad, global spaces.17 This has certainly been the case in arenas such as Oceania, where Malinowski famously did so with shells and the orbit of maritime kula networks, but this approach can also be mapped on to the Philippines as well. As items that allow us a nuanced glimpse into the ethnohistorical past of an archipelago of 7,000 islands, trade ceramics should hold a similar place of honor in blurring the boundaries between history and anthropology.

Notes

For three further studies along Marxist lines, see Miller (1998, 2005) and Apter and Pietz (1993). For a phenomenological reading, see Munn (1986a, 1986b).

See, for example, Stoler (1985), Siegel (2000), and Hickey (1982).

An extremely useful statement of the various actors and routes involved in getting Chinese (and other) porcelain into the Philippines is provided by Long (1992: 44–60).

For the influence of particular Chinese kilns involved in the export trade to the Philippines, and problems of dating through their manufacture, see Chinese and South-East Asian White Ware Found in the Philippines (1993: 10–11) and Evangelista (1989: 15–28).

Three excellent sources that contain a broad spectrum of data on all of the above-mentioned aspects of ceramic production and aesthetics are the Oriental Ceramic Society of Hong Kong (1979), Shanghai Institute of Ceramics (1986), and Penkala (1963: 89–124).

Because high-fire ceramics were produced in Siam, Vietnam, and Burma, but not in the Philippines, the latter archipelago is actually fairly underrepresented in literature on ceramics in Southeast Asian societies. See, for example, Rooney (1987), Guy (1989), and Brown (1988), three standard reference works on porcelain and celadons in Southeast Asia, none of which devote significant space to the history of these objects in the Philippines.

For two good sources on indigenous Filipino ceramic traditions, see Main (1982) and Scheanes (1977: 182).

Addis (1976: 1–20) and Gotuaco, Tan, and Diem (1997) provide useful summaries of the Chinese data on export ceramics in the Philippines.

A useful list of Filipino peoples participating in jar burial complexes, which supplements the data of this earlier source, is Barbosa (1992: 70–94).

For the larger structures of trade, movement, and alliance through which export ceramics traveled, see Casino (1976: 26–30) and Bacdayan (1967: 43–50).

Further data on the Santa Ana site, and other regional caches, can be found in Evangelista et al. (1981: appendix 5) and SEAMEO Project in Archaeology and Fine Arts (1985): 11–13.

For another early discussion of sacred jars further to the south in Mindanao, see Garvan (1929: 1–265).

It is difficult to ascertain if this would have been the case in all of these transactions; very likely this would have been continually negotiated over time by different communities.

Function was important but by no means the only gradient for making these decisions.

Rena Lederman’s article on Highland New Guinea is invaluable here, as it traces (through the wonderful example of a Mendi boy who always wore a single sneaker) how this process can unfold in different contexts. See Lederman (1986: 168).

Of course, some of this notion had been articulated just previously to Hoskins by Arjun Appadurai (1986); it is safe to say that the reverberations of his volume were seismic, both in anthropology and in other disciplines, including history.

See, for example, the entire issue of History and Anthropology fairly recently devoted to these questions across the wide ethnohistorical expanse of Austronesia in Jolly and Mosko (1994).

Bibliography

Addis, J. M. 1976. “Early Blue and White Excavated in the Philippines.” Manila Trade Pottery Seminar: Introductory Notes 4: 1–20.

Aduarte, Diego. 1903a. “Historia de la Provincia del Santo Rosario de Filipinas, 1693.” In Emma Blair and James Robertson, eds., The Philippine Islands 1493–1803 (Translations from the Primary Documents), vol. 31. Cleveland: Arthur Clarke Company.

———. 1903b. “Historia de la Provincia del Santo Rosario de la Orden de Predicadores, 1640.” In Emma Blair and James Robertson, eds., The Philippine Islands 1493–1803 (Translations from the Primary Documents), vol. 30. Cleveland: Arthur Clarke Company.

Agnew, Jean-Christophe. 1990. “History and Anthropology: Scenes from a Marriage.” Yale Journal of Criticism 3(2): 30–46.

Appadurai, Arjun, ed. 1986. The Social Life of Things: Commodities in Cultural Perspective. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Apter, Emily, and William Pietz, eds. 1993. Fetishism as Cultural Discourse. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

Bacdayan, Albert. 1967. “The Peace Pact System of the Kalingas in the Modern World.” Doctoral thesis, Anthropology Department, Cornell University.

Baradas, David. 1995. Land of the Morning: Treasures of the Philippines. San Francisco: Craft and Folk Art Museum.

Barbosa, Artemio. 1992. “Heirloom Jars in Philippine Rituals.” In Cynthia O. Valdes, Kerry Nguyen Long, and Artemio C. Barbosa, A Thousand Years of Stoneware Jars in the Philippines. Makati City, Philippines: Vera Reyes, 70–94.

Berger, Arthur Asa. 1992. Reading Matter: Multidisciplinary Approaches and Perspectives on Material Culture. London: Transaction Publishers.

Beyer, H. O. 1947. “Outline Review of Philippine Archaeology by Islands and Provinces.” The Philippine Journal of Science 77: 3–4.

Boxer, C. R. 1958. “A Late Sixteenth-Century Manila Manuscript, Translated by C. Quirino and M. Garcia, ‘The Manners, Customs, and Beliefs of the Philippine Inhabitants of Long Ago.’ ” The Philippine Journal of Science (Manila) 87.

Bronson, Bennet. 1977. “Exchange at the Upstream and Downstream Ends: Notes Toward a Functional Model of the Coastal State in Southeast Asia.” In Karl L. Hutterer, ed., Economic Exchange and Social Interaction in Southeast Asia: Perspectives from Prehistory, History, and Ethnography. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Southeast Asia Program, 39–52.

Brown, Roxanna. 1988. The Ceramics of South-East Asia: Their Dating and Identification . Singapore: Oxford University Press.

Cannell, Fenella. 1999. Power and Intimacy in the Christian Philippines. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Carson, James Taylor. 2002. “Ethnogeography and the Native American Past.” Ethnohistory 49(4): 769–788.

Carswell, John. 2000. Blue and White Chinese Porcelain Around the World. London: British Museum Press.

Casal, Gabriel et al. 1981. The People and Art of the Philippines. Los Angeles: UCLA Museum of Cultural History.

Casino, Eric. 1976. The Jama Mapun: A Changing Samal Society in the Southern Philippines. Quezon City: Ataneo de Manila Press.

Chau Ju Kua. 1966. His Work on the Chinese and Arab Trade in the Twelfth and Thirteenth Centuries. Friedrich Hirth and W. W. Rockhill, trans. New York: Paragon Book Reprint Company.

Chinese and South-East Asian White Ware Found in the Philippines. 1993. Singapore: Oxford University Press.

Chirino, Pedro. 1903. “Relacion de las Filipinas, 1604.” In Emma Blair and James Robertson, eds., The Philippine Islands 1493–1803 (Translations from the Primary Documents), vol. 12. Cleveland: Arthur Clarke Company.

Christie, Emerson Brewster. 1909. The Subanuns of Sindangan. Manila: Bureau of Printing.

Cohn, Bernard. 1987. An Anthropologist Among the Historians and Other Essays. New Delhi: Oxford University Press.

Cole, Fay-Cooper. 1912. Chinese Pottery in the Philippines. Chicago: Field Museum of Natural History.

Conklin, Harold. 1980. Ethnographic Atlas of Ifugao: A Study of Environment, Culture, and Society in Northern Luzon. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Corn, Joseph. 1996. “Object Lessons, Object Myths? What Historians of Technology Learn from Things.” In David Kingery, ed., Learning from Things: Method and Theory of Material Culture Studies. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution Press, 35–54.

Dant, Tim. 1999. Material Culture in the Social Word: Values, Activities, Lifestyles. Philadelphia: Open University Press.

Evangelista, Alfredo. 1989. “The Problem of Provenance in Manufacture of Chinese Trade Ceramics Found in the Philippines.” In Roxanna Brown, ed., Guangdong Ceramics from Butuan and Other Philippine Sites. Singapore: Oxford University Press, 15–28.

Evangelista, Alfredo, et al. 1981. “Country Report for the Philippines.” In SEAMEO Project in Archaeology and Fine Arts, SPAFA Final Report: Technical Workshop on Ceramics. Kuching: SPAFA.

Fox, Robert. 1959. “The Catalagan Excavations.” Philippine Studies 7 (August).

———. 1982. Tagbanuwa: Religion and Society. Monograph no. 9. Manila: National Museum.

Garvan, John. 1929. “The Manobos of Mindanao.” Memoirs of the National Academy of Sciences 23: 1–265.

Geertz, Clifford. 1980. Negara: The Theatre State in Nineteenth-Century Bali. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Gotuaco, Larry, Rita C. Tan, and Allison I. Diem. 1997. Chinese and Vietnamese Blue and White Wares Found in the Philippines. Makati City, Philippines: Bookmark Books.

Guy, John. 1989. Ceramic Traditions of South-East Asia. Singapore: Oxford University Press.

Hickey, Gerald. 1982. Sons of the Mountains: Ethnohistory of the Vietnamese Central Highlands to 1954. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Hobson, R. L. 1962. The Wares of the Ming Dynasty. Rutland, VT: Charles Tuttle and Co.

Honey, William Bowyer. 1954. The Ceramic Art of China, and Other Countries of the Far East. New York: Beechhurst Press.

Hoskins, Janet. 1998. Biographical Objects: How Things Tell the Stories of People’s Lives. New York: Routledge.

Hutterer, Karl L., ed. 1977. Economic Exchange and Social Interaction in Southeast Asia: Perspectives from Prehistory, History, and Ethnography. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Southeast Asia Program.

Janse, Olov. 1944. “Notes on Chinese Influence in the Philippines in Pre-Spanish Times.” Harvard Journal of East Asiatic Studies 8.

Jolly, Margaret, and Mark Mosko. 1994. “Special Issue: Transformations of Hierarchy: Structure, History, and Horizon in the Austronesian World.” History and Anthropology 7: 1–4.

Kamar, Aga-Oglo 1961. “Ming Porcelain from Sites in the Philippines.” Asian Perspectives 5.

Laufer, Berthold. 1907. “The Relations of the Chinese to the Philippine Islands.” In Smithsonian Miscellaneous Collection 1, Part 2. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution.

Leach, Edmund. 1974. Political Systems of Highland Burma: A Study of Kachin Social Structure. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Lederman, Rena. 1986. “Changing Times in Mendi: Notes Toward Writing Highland New Guinea History.” Ethnohistory 33(1): 1–30.

Locsin, Leandro, and Cecilia Locsin. 1970. Oriental Ceramics Discovered in the Philippines. 2nd ed. Rutland, VT: Charles E. Tuttle.

Long, Kerry Nguyen. 1992. “History Behind the Jar.” In Cynthia O. Valdes, Kerry Nguyen Long, and Artemio C. Barbosa, A Thousand Years of Stoneware Jars in the Philippines. Makati City, Philippines: Vera Reyes, 25–69.

Lopez, Violeta B. 1976. The Mangyans of Mindoro: An Ethnohistory. Quezon City: University of the Philippines Press.

Main, Dorothy. 1982. The Calatagan Earthenwares: A Description of Pottery Complexes Excavated in Batangas Province, Philippines. Manila: National Museum of the Philippines.

Miller, Daniel, ed. 1998. Material Cultures: Why Some Things Matter. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

———. 2005. Materiality. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

Munn, Nancy D. 1986a. The Fame of Gawa: A Symbolic Study of Value Transformation in a Massim (Papua New Guinea) Society. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

———. 1986b. Walbiri Iconography: Graphic Representation and Cultural Symbolism in a Central Australian Society. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Oakdale, Suzanne. 2001. “History and Forgetting in an Indigenous Amazonian Community.” Ethnohistory 48(3): 381–402.

Oriental Ceramic Society of Hong Kong. 1979. South-East Asian and Chinese Trade Pottery. Hong Kong: Hong Kong Museum of Art.

Otley Beyer, H. 1947. “Outline Review of Philippine Archaeology by Islands and Provinces.” Philippine Journal of Science 77 (July–August): 3–4.

Penkala, Maria. 1963. Far Eastern Ceramics: Marks and Decoration. The Hague: Mouton and Company.

Pigafetta, Antonio. 1903. “Primo Viaggio Intorno al Mondo, 1525.” In Emma Blair and James Robertson, eds., The Philippine Islands 1493–1803 (Translations from the Primary Documents), vol. 33. Cleveland: Arthur Clarke Company.

Quirino, Carlos, and Mauro Garcia. 1958. “The Manners, Customs, and Beliefs of the Philippine Inhabitants of Long Ago: Being Chapters of ‘A Late 16th Century Manila Manuscript,’ ” translated, transcribed and annotated. Philippine Journal of Science 87(4) (December): 389–445.

Rafael, Vicente. 1993. Contracting Colonialism: Translation and Christian Conversion in Tagalog Society Under Early Spanish Rule. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

Ridho, Abu, and E. Edwards McKinnon. 1979. The Pulau Buaya Wreck: Finds from the Song Period. Jakarta: Ceramic Society of Indonesia.

Riquel, Hernando. 1903. “Las Nuevas Quescriven de las Yslas del Poniente, 1573.” In Emma Blair and James Robertson, eds., The Philippine Islands 1493–1803 (Translations from the Primary Documents), vol. 3. Cleveland: Arthur Clarke Company.

Rooney, Dawn. 1987. Folk Pottery in South-East Asia. Singapore: Oxford University Press.

Rosaldo, Renato. 1980. Ilongot Headhunting, 1883–1974: A Study in Society and History. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

Roxas-Lim, Aurora. 1966. “Chinese Pottery as a Basis for the Study of Philippine Proto-History.” In Alfonso Felix Jr., ed., The Chinese in the Philippines 1570–1770, vol. 1. Manila: Solidaridad Publishing House.

———. 1987. The Evidence of Ceramics as an Aid in Understanding the Pattern of Trade in the Philippines and Southeast Asia. Bangkok: Chulalongkorn University Asian Studies Monographs.

Salomon, Frank. 2002. “Unethnic Ethnohistory: On Peruvian Peasant Historiography and Ideas of Autochthony.” Ethnohistory 49(3): 475–506.

Scheans, Daniel. 1977. Filipino Market Potteries. Manila: National Museum of the Philippines.

SEAMEO Project in Archaeology and Fine Arts (SPAFA). 1985. SPAFA Final Report: Technical Workshop on Ceramics. Bangkok: SPAFA.

Shanghai Institute of Ceramics, Academia Sinica. 1986. Scientific and Technological Insights on Ancient Chinese Pottery and Porcelain. Beijing: Science Press.

Siegel, James. 2000. The Rope of God. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

Silverman, Eric Kline. 1990. “Clifford Geertz: Toward a More ‘Thick’ Understanding?” In Christopher Tilly, ed., Reading Material Culture: Structuralism, Hermeneutics and Post-Structuralism. Oxford: Basil Blackwell, 121–159.

Solheim, W. G. 1959. “Notes on Burial Customs in Near Sagada Mountain Province.” Philippine Journal of Science 88: 123–133.

———. 1960. “Jar Burial in the Babuyan and Batanes Islands, and Its Relationship to Jar Burial Elsewhere in the Far East.” Philippine Journal of Science 84(1): 15–148.

———. 1964. “Pottery and the Malayo-Polynesians.” Current Anthropology 5(5) (December): 368–375.

———. 1965. “The Functions of Pottery in Southeast Asia: From the Present to the Past.” In Frederick Mason, ed., Ceramics and Man. New York: Wenner-Gren Foundation for Anthropological Research, 254–273.

Stark, Miriam. 1994. “Pottery Exchange and the Regional System: A Dalupa Case Study.” In William Longacre and James Skibo, eds., Kalinga Ethnoarchaeology: Expanding Archeological Method and Theory. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution Press, 169–198.

Stoler, Ann. 1985. Capitalism and Confrontation in Sumatra’s Plantation Belt, 1870–1979. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Tenazas, Rosa C. P. 1973. “Notes on a Preliminary Analysis of Cremation Burial.” Philippine Quarterly of Culture and Society 1(2).

———. 1984. “Evidences of Cultural Patterning as Seen Through Pottery: The Philippine Situation.” In Studies on Ceramics. Jakarta: Proyek Penelitian Purbakala.

Tite, Michael. 1996. “Dating, Provenance, and Usage in Material Culture Studies.” In David Kingery, ed., Learning from Things: Method and Theory of Material Culture Studies. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution Press, 231–260.

Trostel, Brian. 1994. “Household Pots and Possessions: An Ethnoarchaeological Study of Material Goods and Wealth.” In William Longacre and James Skibo, eds., Kalinga Ethnoarchaeology: Expanding Archeological Method and Theory. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution Press, 209–223.

Warren, James Francis. 1981. The Sulu Zone: The Dynamics of External Trade, Slavery, and Ethnicity in the Transformation of a Southeast Asian Maritime State. Singapore: Singapore University Press.

Wilson, Elizabeth. 1988. A Guide to Oriental Ceramics in the Philippines. Manila: Bookmark Books.

Wong, Grace. 1978. “Chinese Blue and White Porcelain and Its Place in the Maritime Trade of China.” In Chinese Blue and White Ceramics. Singapore: SEACS, 175–182.