Subjectivism as content: knowledge

In recent years the economics of knowledge has received considerable attention. It is not our purpose to retrace its development. Instead, we shall concentrate on a number of critical issues that have not been explored in this literature. The neglect of these issues stems from the nonsubjectivist perspective adopted by most information theorists. Our analysis will stress precisely those subjectivist themes that tend to be absent in the conventional approaches. Specifically, we shall divide our discussion into four subsections: (1) the context of the individual’s knowledge; (2) the nature of learning; (3) the division of knowledge in society; and (4) the difference between scientific and nonscientific knowledge.

The context of knowledge

An individual’s knowledge always arises in the context of a problem situation (Popper, 1979b). The static version of “situational analysis” consists simply of a precise statement of a problem, the background to that problem, and the framework of its solution. From the economic perspective, the problem situation is interpreted as focusing around a means-ends relationship. Consider, for example, the problem of want satisfaction. The background to this is knowledge of the relationship between commodities or courses of action and want satisfaction. The framework is the assumed motivation of utility maximization and the price-income constraints. Thus, from the point of view of situational analysis, the task of the economist is to reconstruct the situation of the actor in terms of achieving the rational solution to a problem as the actor saw it.

The emphasis on the rational solution to a problem differentiates this form of analysis from a psychological subjectivism that often appeals to notions of “irrationality.” In addition, our approach differs from that of individual psychology insofar as there is no real-world individual-by-individual investigation of perceptions. Instead, there is only a conjecturing of the perceptions of an ideal-typical individual or mind construct. More generally, because no direct observation of what the individual “sees” is possible, the problem situation must be hypothesized in the context of the overall outcome the analyst wishes to explain.

Situational analysis need not imply, however, that the behavior of the individual be determinate as the solution of a mathematical problem would be. We must clearly allow for dynamic or nondeterministic situational analysis (Popper, 1979b, p. 178). Fundamentally, the problem-solving logic is a rationalization or reconstruction of a situation. “When we speak of a problem, we do so almost always from hindsight. A man who works on a problem can seldom say clearly what his problem is (unless he has found a solution)…” (Popper, 1979a, p. 246). The indeterminism inherent in the actual situation is thus evident when we try to reconstruct matters as the actor saw them ex ante. From that perspective, the statement of the problem will not be very precise, and, hence, an exact solution cannot be determined in advance.

The nature and process of learning

Merely to confine ourselves to rational reconstruction of problem situations does not tell us anything about how the individual sets up the problem context. Learning is thus not usefully explained in terms of the logical working out of a given, carefully specified problem. Recall that the consumer’s problem under static conditions is reduced to mere computation of a constrained maximum. Because economic agents are assumed always to be rational, they don’t even take time to compute such solutions. “True” learning involves more than mathematical computation; rather it consists of the setting up of the problem situation itself or the movement from one problem situation to another. This is analogous to Hahn’s distinction between different solutions to the same learning function (as the data change) and different functions themselves. Learning takes place when the individual’s framework of interpreting external “messages” or stimuli has changed over time (Hahn, 1973, pp. 18–20). At present, we do not have a theory that enables us to say something significant about the move from one problem context to another. Nevertheless, we can go beyond Hahn’s remarks and say something about how such a theory might look.

Theories about genuine learning cannot be deterministic. If we try to force learning into such a mold, we shall lose any notion of creative response. We have already seen the inconsistency involved in constructing deterministic theories of processes. In addition, because individuals undoubtedly perceive a nondeterministic element in their learning experiences, this must affect how and why they act. Nevertheless, to claim that learning is not deterministic is not thereby to assert that it is purely random. Popper has elucidated, at least in general terms, the idea of a “plastic control” (Popper, 1979a, p. 240) standing between mechanical determinism on the one hand and blind chance on the other. While the details of this idea are based on a theory of scientific progress that we do not entirely share, it is nonetheless important to model the learning process in a way that attempts to formalize Popper’s intuition.

Learning in this Popperian sense is evident in the Austrian theory of entrepreneurship. In that theory we assume only the “tendency for a man to notice those [facts] that constitute possible opportunities for gainful action on his part” (Kirzner, 1979a, p. 29; emphasis added). In addition, “human action involves [merely] a posture of alertness toward the discovery of as yet unperceived opportunities and their exploitation” (Kirzner, 1979a, p. 109; first emphasis added). The process of entrepreneurial learning is neither determinate nor random. With respect to this “in-between” world of plastic control, two important points can be made. First, although what individuals will learn is not determinate, that they will learn something may well be. In fact, this is the fundamental assumption of the theory of entrepreneurship. We are willing to say a priori that learning will take place. Second, given the overall context of a change in knowledge, we can show how the move from framework1 (F1) to framework2 (F2) is intelligible, in the sense that a metatheory can be constructed in which a loose dependency on F1 is shown. F2 is more likely (though not necessarily highly likely or probable) given F1 than it would be given some other F′1. On the other hand, we might say that, given F1, many possible alternative frameworks can be ruled out and that only a class of subsequent frameworks (which includes F2) can be determined.

The division of knowledge

One of the criteria for the type of knowledge we can attribute to the mind construct is whether it is plausible (intelligible) that the knowledge would have been acquired in the postulated context. Fundamentally, this context is the individual’s system of relevances (Schutz and Luckmann, 1973, pp. 182–229) – what he deems important. This, in turn, is dependent on his goals, the perception of opportunities, etc., or, in short, on the problem situation he faced in the previous period. Primarily because different people face different problems, there is a division or distribution of knowledge in society (Schutz and Luckmann, 1973, p. 306). It is not plausible to argue that, regardless of the situation, individuals find that they will ultimately learn the same things. Further, even if all individuals faced the same problems, they would probably not all have the same ability to acquire knowledge. There would still be a distribution of knowledge, although the “stock” of knowledge would be equally useful to everyone. Merely because people faced different problems does not mean, however, that all of the knowledge acquired by one individual is irrelevant to the others. Hence, knowledge must be communicated.

Consider the case of a reduction in the supply of steel. Those in the industry itself may know that a rise in the price of coal is partly to blame for the increased cost of production and therefore the reduced supply. But the causes of supply reduction may be irrelevant or, at least, less relevant to the builders of houses. They need know only a part of what the steel producers know: merely that steel has become relatively more scarce. Thus, some knowledge will remain uncommunicated while other bits of knowledge will be transmitted. For our purposes there are two important ways for knowledge to be communicated: through prices and through institutions.

Prices In the previous example, the price of steel would rise, thus conveying information about the relative reduction in supply (Hayek, 1940). But price signals need not always be correct. Suppose the same steel producers mistakenly believe that there has simultaneously been a decrease in the demand for products using steel as an input. They might actually attempt to lower the price.1 The issue is not, however, the accuracy of the price signal relative to some external standard of perfection. Prices, we admit, can and will be incorrect. The crucial point is that, overall, more information is conveyed through a market price system than without one (Hayek, 1937a, 1935a, 1935b). Further, even “incorrect” (i.e., nonequilibrium) prices convey information by revealing inconsistencies and plan discoordination (Kirzner, 1984).

Institutions Information is also conveyed outside the price system through patterns of routine behavior. Institutions may transmit knowledge in two senses. First, if people can rely on others to fulfill certain roles then their expectations are more likely to be coordinated. If, for instance, an individual knows that the sanitation department will pick up his garbage in the morning, then he can make use of the knowledge of garbage disposal that is possessed by others. What is transmitted to him is not that knowledge itself but the knowledge of how to make effective use of skills he will never possess (Sowell, 1980, pp. 8–11).

Second, some have argued (e.g., Hayek, 1973) that institutions also convey knowledge, in the sense that the routine courses of action they embody are efficient adaptations to the environment. A vague Darwinian process is postulated which weeds out institutions with inferior survival properties. There are several problems with the view. Unless the nature of these survival properties is made clear, the whole “theory” is little more than a tautology. Survival properties are, by definition, those attributes that enable an institution to survive. Hence in any “conflict” among institutions those with inferior survival properties must necessarily give way to those with superior properties. Unfortunately, as the theory now stands, a careful specification of what makes societies survive has not been achieved. The second problem with the “Darwinian” view of institutions arises out of indivisibilities. The routine courses of action that comprise an institution are not all independent; the Darwinian process cannot eliminate all but the very best routines and combine them into a consistent or coordinated whole. Some clearly inferior routines must be maintained in order to permit those clearly superior (but dependent) to exist. Furthermore, nature does not throw up an infinite number of institutions out of which only the best will survive. The choice set, so to speak, is normally quite limited. The implication of these considerations is that, in the absence of a clear conception of the nature of survival properties, we cannot know whether any given institution or course of action is the most adaptive. In fact, we know that many institutions will not be the most adaptive possible because of indivisibilities in the evolutionary process.

Are prices and institutions objective knowledge?

The transmission of knowledge through prices and institutions does not mean that subjectivity is no longer important and knowledge has in effect, become objectified. It is a misconception of subjectivism to assume that it deals with only elements of the individual psyche that can never be intersubjectively communicated. The social world is preeminently an intersubjective world (Schutz, 1954), and the phenomena in which we are ultimately interested rest on this fact. To say that knowledge has been transmitted from A to B means that where there was initially only one mind there are now two. Subjectivism is now more, not less, important than before. The nature of what is transmitted – the thoughts of individuals – is subjective. Similarly, the modes of transmission must be interpreted by those who receive the signals. A price or an institutional code of behavior must mean something in order to be an effective communication device. A rise in the price of a given commodity, for example, will have different meanings depending on the “elasticity of expectations” of the receiver. A price rise may signal higher or lower future prices when the subjective context of the date is taken into account.

Although the process of transmission enables individuals to make use of widely dispersed knowledge, it does not eliminate the heterogeneity of individual stocks of knowledge. Because people misinterpret signals, communication is imperfect. What the sender sends is often not what the receiver receives. Furthermore, information transmission is costly. At the very least, individuals must pay attention to prices, and they must recognize or understand how institutions function. Thus, there is an optimal amount of transmission and hence a degree of heterogeneity of knowledge that is irreducible.

But even when it pays to communicate, the sequence or order of knowledge acquisition will probably not be the same for all actors (Schutz and Luckmann, 1973, p. 307). If, for example, the individual who directly acquired bits of information a1, a2, a3, a4 did so in that order, another individual might acquire this same information in reverse order, a4, …, a1. This means, however, that their stocks of knowledge will ultimately be different. The “meta-” knowledge of relationships among these elements can depend upon the order in which they are apprehended. It is also the case that the nature of communication itself makes it impossible for all heterogeneity to be eliminated. So long as knowledge is communicated rather than directly acquired, the context of its original acquisition will be unknown to some. As a consequence, not all individuals will understand the full context and hence the full meaning of the “communicated” knowledge.

Because of (1) differences in the problem situations that individuals face and (2) the very nature of the communication process, there exists no presumption that knowledge will be uniformly distributed: it will always be divided. Even in equilibrium,2 then, not everyone will know the same things.

To talk of a “social stock of knowledge” is therefore merely a shorthand way of referring to its distribution across society. This social stock, however, bears no simple relationship to the individual stocks. It is both less and more than their summation. It is less because not everything that is relevant to each individual taken separately is in their common interest (Schutz and Luckmann, 1973, p. 289). It is more because new knowledge arising out of combinations of the old “isolated” elements is now possible.

The relationship between the two stocks of knowledge is compositive. An initial social stock is built up from the individual stocks on the basis of common relevances. Then the individual is able to increase his knowledge still further by establishing interconnections among the now-collected bits. By so doing, the social stock on which individuals can draw is expanded as this new derivative knowledge spreads. The process can continue even if underlying objective conditions remain unchanged. There is no end to the enrichment of the social stock of knowledge except the largely unexplored limitations of the human mind. Thus we must reject any notion of a final “equilibrium” state of knowledge.

Scientific knowledge

In the previous section we explored some fundamental aspects of the individual and social stock of knowledge as “data” of economics. In this section we wish to emphasize the important differences between the subjectivity of the subject matter and the subjectivism of our method of investigation. Subjectivism as a method is perfectly consistent with objective science. In order to see this, we must consider two component issues: first, the difference between scientific knowledge and knowledge of the mind construct; second, the possibility of having an objective science of subjective meaning.3

The key to the difference between the level of knowledge of the scientist and that of the economic actor or mind construct lies in the different problem situation faced by the two. The typical scientific question investigates the overall, frequently unintended, consequences of individual action. Individuals, on the other hand, are not always interested in those consequences.

Consider, for example, the well-known scientific question, does capital, labor, or the consumer bear the burden of the imposition of a corporate income tax? For the individual actors this issue can be decomposed into several subissues: savers must decide whether to continue the same rate of saving; investors must decide whether to reshuffle their portfolios; laborers must decide whether to shift jobs in response to any change in wage rates; and, finally, consumers must decide whether to shift product mixes. Each of these actors makes his own marginal adjustments without necessarily understanding the interaction and overall result of those adjustments. If, on the other hand, they are faced with the political question of whether to support the corporate income tax, the overall result or net burden may be a part of their problem situation.

This does not mean, however, that the actors understand the relevant scientific theory. A further argument must be constructed that will show that this knowledge can be communicated from scientists to nonscientists. More importantly, actors are normally faced with several models of an economic problem. They must choose among scientific theories. The proponent of the “correct” theory has no assurance that actors will believe his theory instead of an “incorrect” one. There is no reason to think that nonscientists will settle on just that theory adopted by the scientist. In the first place, even scientific standards of theory acceptance or rejection are controversial and highly ambiguous (Feyerabend, 1975; Kuhn, 1970; Lakatos, 1970). So there is a large range of indeterminacy that will surround the choice of theories. In the second place, scientific standards do not necessarily coincide with those of the actors. Suppose, for example, that a model explains the effects of a tax on X and Y. Because of the problem in which the actor is interested, he may be more concerned about inaccuracies in the explanation with respect to X alone. The scientist, on the other hand, may be interested in minimizing the sum of the errors with respect to X and Y. Hence, each may be led to select a different theory on the basis of different standards of performance.

The second issue concerns the status of an objective science of subjective meaning. The possibility of such a science rests on the method of idealized rational reconstruction (whether deterministic or nondeterministic) of a problem situation. At the most abstract level, the problem situation need not embody reference to any concrete goals or constraints. Instead, we may be content to work out merely the formal implications of purposiveness. The law of diminishing marginal utility, for example, says a great deal about the structure of action in a static context, while completely abstracting from the content of individual ends. Objective science at this level is the development of a logic of choice that transcends the context in which particular individuals find themselves.

On an applied level, however, the economist cannot abstract from the typical contents of actors’ minds. He must incorporate these into explanations of real-world phenomena. Although direct observation of subjective contents (tastes, expectations, etc.) is not possible, applied economics can still have intersubjective validity. The knowledge attributed to the mind construct must bear an “understandable” relation to the behavior under study. Therefore, our attribution of subjective states is always “controlled” by the real-world actions they are meant to illuminate. In addition, the contents of the actors’ minds must be assumed to be consistent with one another in the specific sense that no one will knowingly believe contradictory things or have contradictory values. Finally, the usefulness of particular subjective states in understanding behavior outside of the immediate context of investigation is important. If, for example, we wish to explain why the price of soybeans has risen, we may want to invoke expectations that the government will impose a general price-increasing regulation on commodities. This specific attribution of content to individuals’ expectations will carry greater scientific weight the more independent evidence that there is for it. Thus, if the behavior of the prices of other commodities, the information-gathering activities of individuals and the announcements of the government are all consistent with our expectational hypothesis, then we can assign it some measure of scientific corroboration. At no time, however, do we directly “see” expectations; rather, we merely observe that there are more and more phenomena consistent with the same subjective state.

The objectivity of the subjectivist method ultimately rests both on the level of analysis pursued by the scientists and on the “controlling” effect of the individual’s behavior. In the first instance, although the knowledge of the scientist incorporates the subjective contents of the actor’s mind, it goes beyond that to a higher level of generalization. This level often concerns the overall unintended consequences of individual actions. Furthermore, even at the individual level, objectivity in the method can be maintained. The imputed knowledge of the mind construct must bear an understandable relation to the behavior we seek to explain. Hence our imputations are controlled at least partially by that behavior.

Subjectivism as weighing of alternatives

For many economists subjectivism means little more than the subjective theory of value. As we have already seen in this and the previous chapter, the nature and implications of subjectivism spread farther and wider than this. Nevertheless, even within the domain of value theory subjectivism has been only partially understood. While value is admittedly subjective, cost has inexplicably been viewed as objective. Thus, the Marshallian blades of the scissor were invented to symbolize the neoclassical fusion of subjective and objective factors. In our view, however, this dichotomization of the value process fails to understand the fundamental principle of subjectivism: valuation is nothing but the mental weighing of alternatives. None of these alternatives is a realized event because choices can be made only between images or projections of the outcomes of various courses of action. When an alternative is realized it is already too late to choose (Buchanan, 1969, p. 43). Subjectivism, then, must suffuse both the theory of value and the theory of cost; both blades of the scissor are made of the same material (Schumpeter, 1954, p. 922).

Utility background

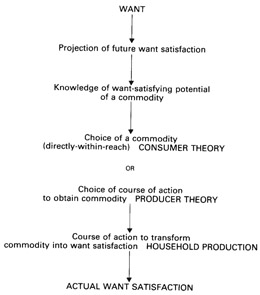

Figure III.1 illustrates in schematic form a thoroughly subjectivist view of value theory. The foundation of all value is a basic human want. In the sense originally conceived by Menger (1981, pp. 52, 139) and more recently developed by Becker (e.g., 1965) and Lancaster (e.g., 1966), wants are not directly for observable goods. Instead, they are for the satisfaction of some more basic desire: music (Stigler and Becker, 1977, p. 78), comfortable indoor temperature, health and delicious meals (Becker, 1971, pp. 47–8) are all examples of basic wants.4

With a background of these wants, the individual projects an image of future want satisfaction. These projections are the immediate motivating source of his activity. Because individuals choose among directly observable goods or observable courses of action that produce these goods, there must be some link between the projected want satisfaction and these observables. This link is the individual’s knowledge of a commodity’s want-satisfying potential, i.e., the perceived production function. The relationship between market commodities and projected want satisfaction is not automatic but depends on the undertaking of a specific course of action to transform the commodity into actual satisfaction. This is the essence of the household production idea, originated by Menger and developed by Becker.

As we have just seen, the relationship between wants and choices of market commodities is not a simple one. “There is many a slip betwixt cup and lip.” The individual may incorrectly attribute want-satisfying potential to a good (Menger, 1981, p. 53; “imaginary good”), or he may ignore such potential when it is actually there. Furthermore, he may find that the costs involved in engaging in a particular plan of household production (in addition to the direct commodity costs) make the achievement of a particular want satisfaction prohibitively expensive.

Utility in this framework refers to the rank ordering of projected want satisfactions. An individual may value the prospective satisfaction of his desire for an additional unit of comfortable indoor temperature more than that of his desire for an additional unit of delicious meals. Strictly speaking, he does not rank the wants themselves, because they are mere deprivations and are not valued. Similarly, he does not rank the market commodities themselves, because they are wanted not for their own sake but only for the satisfaction they indirectly produce.

It is true that if we viewed the link between commodities and satisfaction as automatic, then little is gained by this separation. The subjectivist view of utility theory must allow, however, for the erroneous perception of such a link. Hence the distinction between commodities and satisfaction is important. Finally, realized (as opposed to projected) want satisfactions cannot be objects over which utility is defined because ex post magnitudes occur too late to motivate behavior. It is only projected satisfaction of wants that can provide the motivating force in decision-making.

In a static equilibrium world, the distinctions, on the one hand, between commodities and the projected satisfactions they can create and, on the other hand, between realized and projected want satisfaction lose much of their force. In the first case, no economically relevant error would enter into the perception of a commodity’s want-satisfying potential. In the second, images or projections of satisfaction would never deviate from the realized event. Thus, one might quite reasonably invoke Occam’s Razor and define utility over market commodities, omitting the intermediate steps.5 However, in a world of disequilibrium, individuals cannot proceed directly and immediately from goods to want satisfaction. In such a world the distinction made in our utility scheme can be quite useful in highlighting the complexities of the decision process.

Cost in consumer decision-making

Cost theory is not really a separate subject from utility theory. The concept of cost follows immediately from the way in which utility is defined. In a subjectivist framework, the cost of choosing any commodity is the highest ranked projected want satisfaction that is perceived to be sacrificed. Cost, just like utility, is defined over projected want satisfaction and not directly over the commodities themselves. The relevant sacrifice cannot be merely the perceived commodity displacement, for the same reason that the relevant motivation for choice cannot be the chosen commodity itself. Commodities are only way stations to the ultimate satisfaction of basic wants. It is these projected satisfactions that constitute both utility and cost.

The only sense in which cost can influence choice is the perception at the very moment of choice of the satisfactions foregone (Wicksteed, 1967, p. 391). Thus, cost is tied to choice and apart from it has no economic meaning (Buchanan, 1969, p. 43). After a choice is made, retrospective calculations of what the relevant costs “really” were (in the sense of what the actor would have perceived if he had had certain superior knowledge) cannot, of course, be relevant to that prior choice situation. To the extent that conditions are expected to remain the same, however, such calculations can inform future choice situations. Nevertheless, even these historical estimates cannot demonstrate unambiguously what would have happened if the individual had chosen another commodity or course of action. It is quite possible that the projected satisfaction associated with a rejected alternative would have never materialized. Thus, even ex post, costs cannot be realized. They must remain forever in a world of projecting, fantasizing or imagining.

Although cost is inextricably bound to the individual’s choice context, it is nevertheless possible for one individual to affect the costs of another. If A pollutes the water (a completed act of choice), then the cost to B of obtaining clean water to drink will increase. The nature of B’s cost is still subjective: the highest ranked projected want satisfaction that he perceives must be sacrificed in order to obtain drinkable water. Nevertheless, this perception is affected by individuals making choices outside of the context in which B’s cost itself affects behavior. This is not the same thing as saying that other individuals strictly “determine” or “impose” costs on any decision-maker. While other people can surely affect the environment of choice, it is still the choosing individual who must ultimately perceive the alternatives sacrificed and bear the costs of his choices. In perfectly competitive equilibrium, the three quantitative magnitudes (foregone revenue, outlay cost and consumers’ valuation) are equal at the margin. This equality at the margin does not imply that the conceptual differences disappear but that they are not manifest in competitive markets in equilibrium.

Cost in the theory of the firm

For heuristic purposes, cost takes on a somewhat different meaning in the theory of the firm. Here, the relevant meaning depends entirely on the imputed objective function of the firm’s decision-maker. If the firm seeks to maximize profits, then cost must be defined in terms of foregone revenue and not in terms of foregone want satisfaction. This is because it is analytically convenient to separate the process by which the firm makes its decisions (theory of the firm) from the process by which the decision-maker buys market commodities and transforms them into want satisfaction (consumer theory). To combine the two in every case would make our efforts to understand market phenomena enormously more complicated without yielding any increased insight. Nevertheless, we must always remember that the ultimate motivation for all choices is want satisfaction. Profit-maximization, sales maximization and other imputed firm goals are only means to the attainment of more basic ends. Thus any assumed motivation should not be viewed as a constant.

For the profit-maximizing decision-maker, cost is the revenue that the decision-maker perceives he could have obtained with the same resources in the best alternative line of endeavor (Thirlby, 1973, p. 277). In contrast to this notion of cost, there are at least two conventional nonsubjectivist concepts. The first is direct outlay cost: this amounts to the expenditures incurred in acquiring the necessary factors of production. The second is a species of “social cost” (Thirlby, 1973, p. 278), referring to the consumers’ valuation of the alternative products that other decision-makers might have produced had a different course of action been undertaken. In perfectly competitive equilibrium, all three notions of “cost” collapse into each other. Assuming that a decision-maker is not restricted to any given industry, his costs will be equal at the margin to the market prices of the resources that he employs.6 This follows because, under competitive conditions, these prices will be bid up to the value of the resources in their best alternative use, regardless of where in the economy that might be. The decision-maker’s costs will also equal the consumer’s valuation of the alternative product because the total value of a commodity on the output market will be the same as its value on the resource market.

In disequilibrium, however, these notions of “cost” need not bear any systematic relation to one another. Therefore, the analyst’s choice of which one he will use is of paramount importance. To understand the decision-making process of the firm, only the first, thoroughly subjectivist, view of cost (the firm’s anticipated foregone revenue) will be useful. Only costs as perceived by the decision-maker in terms of his own options are relevant to understanding his behavior. Direct outlay cost in conjunction with the implicit market value of factors owned by the decision-maker will, on the other hand, be useful in calculating entrepreneurial profit. The difference between total revenue and these expenses represents profit from the market point of view. Finally, a comparison of the consumer valuation of alternative products and the costs as perceived by the firm tells us something about how well the market is satisfying consumer demands. When firm decision-makers view alternative A as preferable to B, and consumers favor B over A, then we have imperfect market coordination.

The three concepts that are conventionally lumped together as “cost” are really very different in analytical function outside of competitive equilibrium. As a consequence, it would seem better to allocate different names to these ideas, reserving the term “cost” for the concept that arises directly from the theory of choice. Implicit or explicit expenses (outlays) and consumer valuations are unambiguously handled by these other terms, and calling them “cost” only creates confusion.