The world has changed tremendously since the first Blackwell edition of the book in 1985, and since the Routledge edition in 1996. There have been very important changes in the economy and in the discipline of economics. Paradoxically, these have made our book much more relevant than it was. The changes in the external world and in the economics profession have destroyed, or at least seriously weakened, many of the taboos that used to dominate economic thought. The passage of time and the growth of knowledge combined to bring about a new era.

It used to be the case that questioning the static nature of competitive theory was not fashionable, but clearly economists are more concerned now about dynamic issues. How could they not when innovations are springing up everywhere around us? The universal applicability of rigid and narrow axiomatic rationality assumptions (preference completeness, transitivity, and independence of framing, etc.) is under severe pressure from behavioral economics. The questioning of these opens the door to a greater appreciation of the pragmatic nature of economic rationality and to the subjective interpretation of economic “data.” We are also now permitted to question the intrapersonal stability of tastes. Economists are thus more willing to embrace the importance of change even at the level of the individual.

The financial crisis of 2007–08 and the associated Great Recession were extremely important economic events that have had a still difficult-to-evaluate impact on economic thinking. The general revival of Keynesian thought during the financial panic and the Great Recession and its aftermath brought with it a renewed appreciation of the old Keynes-Hayek debate as it became obvious that Keynes and Hayek were the true antipodes on the fundamental macroeconomic issues. We were extremely interested in this in our book – as well as in those areas in which we believe Keynes had valuable things to say.

The importance of Knightian and radical uncertainty has not gone unnoticed by economists in view of the financial crisis. We remember many neoclassical economists saying that the distinction between risk and uncertainty is not very important. Situations could be modeled, they said, as if they were merely risky, especially in light of subjective probability. However, insofar as the riskiness of new asset forms were judged by the “stable” data of recent history the possibility of structural change was ignored to the detriment of all.

The rule of law (a topic long of concern to Hayek) became an issue of renewed importance in understanding the policy response to the financial crisis, the Great Recession and other problems. Increasingly critics worried about the violations of the rule of law in Federal Reserve policy, in TARP and in the auto bailout.1

These developments naturally led to an accelerated appreciation of the importance of institutions. This was a development that had been gaining importance, perhaps ever since the work of Ronald Coase. But institutions become even more important – a matter of economic life or death – during rough patches.

Institutions cannot be fully understood except in the context of local knowledge, another Hayekian theme, as was seen in the still-limited recovery from Hurricane Katrina in New Orleans.2 In a development-economics context, the neglected importance of local knowledge became a critical point in analyzing what critics believe is the overall failure of World Bank policies.

Thus, the shifting and dissolution of scientific taboos and the recognition of certain “Austrian issues” promoted by recent events, even when they are not recognized as Austrian, have given the ideas in the book new and heightened relevance. We believe that our ideas provide, in many cases, an alternative to the increasingly obvious poverty of standard approaches.

The plan

In this new introduction there will be two main parts. In the first we sketch the impact of recent economic history on (mainly) the macroeconomic and monetary ideas that we sought to promote in this book. In the second we describe recent developments in behavioral economics that strengthen the case for our general approach.

I. The impact of economic crises

The financial crisis began with the Panic of 2007, and continued into 2008 with multiple crisis events involving, among others, mortgage giants Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac; failed investment banks like Bear Stearns (bailed out) and Lehman Brothers (not bailed out); and many financial firms whose solvency was in doubt at some point (e.g., Citigroup and Morgan Stanley).3 The Panic involved a great housing boom financed by innovative financial instruments. After the housing boom ended there was a crisis in housing finance involving actual or perceived insolvency of firms at the center of housing finance.

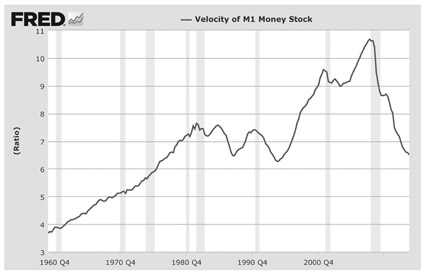

The crisis occurred in the midst of a period known as the Great Moderation (Taylor, 2009, pp. 34–46). It was a period in which the growth rates of monetary aggregates moderated. Macroeconomic flow variables, like real GDP, became less volatile. But it was also a period of a great expansion in the velocity of the M1 monetary aggregate.

The increase in velocity, or decrease in money demand, accompanied the rise of “shadow banking,” in which housing loans (and other bank lending) were securitized. Long-term debt, like home mortgages, was increasingly financed by short-term credit, even overnight funding as was so famously the case with Lehman Brothers. A credit pyramid was erected upon a narrow base of bank money. The possession of Treasury securities or other eligible collateral financed transactions in repo (overnight repurchase agreements) markets. Gorton succinctly described the process.

Another important feature of repo is that the collateral can be rehypothecated. In other words, the collateral received by the depositor can be used – “spent” – in another transaction, i.e., it can be used to collateralize a transaction with another party. Intuitively, rehypothecation is tantamount to conducting transactions with the collateral received against the deposit. There is no data on the extent of rehypothecation.

(Gorton, 2010, p. 44)

Traditional banking was increasingly being replaced by securities markets. Banks and thrift institutions continued to play a role in originating home mortgages (though origination was also done by mortgage companies). But they no longer held the mortgages, which were bundled with others and sold off as securities. Information about the underlying risk of each mortgage was lost in the process. Yet securitization only grew. Investment banks supplanted commercial banks, and repo markets grew in importance relative to the federal funds market.

During the crisis, the repo market dried up. But so, too, has the federal funds market. The Federal Reserve’s extraordinary monetary policy actions (quantitative easing or QE) have made it, and not interbank lending, the source of liquidity in banking. Today the Federal Reserve is increasingly operating in repo markets.4

The conventional modern analysis of risk was challenged by these developments in financial markets. The challenge has been analyzed in two, ultimately complementary, ways. One line of analytical criticism of standard risk models we will describe as immanent. It questions the properties of the distribution of risk. Standard risk analysis models risk with a Gaussian distribution. That is typically described as a normal or bell curve. The events in the recent financial crisis suggest “that financial returns are not Gaussian – or even remotely so” (Dowd et al., 2011, p. 14).

The Cauchy distribution is one “fat-tail” distribution, and it is reproduced here along with a normal distribution. The Cauchy distribution implies that “extreme losses are much more likely than under the Gaussian” (Dowd et al., 2011, p. 14). How much more likely? In August 2007, Goldman Sachs’ CFO David Viniar stated that “we were seeing things that were 25-standard deviation moves, several days in a row.”5 Dowd et al. estimate that a single 25-standard deviation event should occur only once every 10 (to the 137th power) years. They conclude that “to be plausible, risk models need to be based on alternative distributions to the Gaussian” (Dowd et al., 2011, p. 14).

Alternatively, one can view recent events as manifestations of Knightian uncertainty. Frank Knight argued there was (1) an absence of objective probabilities and (2) an inability to list, or determine beforehand, the complete set of possible outcomes. Risk managers extrapolated recent history to model the riskiness of new types of complex and bundled securities, especially mortgage-backed securities (MBS). In 2009, Edmund Phelps asked rhetorically, “why did big shareholders not move to stop over-leveraging before it reached dangerous levels? Why did legislators not demand regulatory intervention?” He went on:

The answer, I believe, is that they had no sense of the existing Knightian uncertainty. So they had no sense of the possibility of a huge break in housing prices and no sense of the fundamental inapplicability of the risk management models used in the banks. “Risk” came to mean volatility over some recent past. The volatility of the price as it vibrates around some path was considered but not the uncertainty of the path itself: the risk that it would shift down. The banks’ chief executives, too, had little grasp of uncertainty. Some had the instinct to buy insurance but did not see the uncertainty of the insurer’s solvency.

(Phelps, 2009)

The Knightian critique is more fundamental, since it questions whether there are discoverable distributions of risk in all instances. Knight certainly recognized that many risks are calculable. Modern risk analysis collapses Knightian uncertainty into quantifiable risk, and then assumes a normal distribution of risk. In the wake of the financial crisis, each of those steps must be questioned.

When the housing boom went bust, economists of the Austrian school saw it as a textbook example of malinvestment ending in a crisis. The Austrian analysis built on that of classical political economy – as Mises, Hayek and others long emphasized (Mises 1966, p. 204). Some financial analysts, economists and members of the public acknowledged the applicability of Austrian analysis. Many members of the economics profession busily defended theories that neither predicted nor accounted for what had happened.

The most surprising thing, however, was that the public policy response was to fall back on crude versions of Keynesian income-expenditure models. Hoary myths of fiscal-expenditure multipliers greater than one were resurrected, in some cases by advisers to President Obama whose own work undermined such beliefs. Of such beliefs, Milton Friedman observed more than 50 years ago that “they are part of economic mythology, not the demonstrated conclusions of economic analysis or quantitative studies” (Friedman, 2002, p. 84). In the ensuing 50 years, a large body of economic research – economic analysis and quantitative studies – debunked that mythology. Much of the work was done by Friedman, his colleagues and students. As this is written, we have just passed the fifth anniversary of the Obama “stimulus” program. No one, to our knowledge, has mounted a serious argument that it had concrete, measurable benefits.

An important conference put on in March 2009 by the Mont Pelerin Society focused on whether the Great Recession was best explained by Austrian economic analysis or that of another school, Keynesian or otherwise. In a seminal paper, Axel Leijohnufvud (2009) examined whether the downturn was one best analyzed by an income-expenditure model, i.e., in terms of economic flows. He concluded that it was not. Instead, he declared it to be a classic balance-sheet recession, and one best analyzed by Austrian analysis.

All of the macroeconomic policies implemented in the Great Recession ignored its character as a balance-sheet recession. When households and businesses are trying to restore their balance sheets and rebuild savings, creating massive new federal debt is counterproductive. But creating future tax obligations for households and businesses is precisely what the stimulus did. There were also other, deleterious microeconomic effects that put more of the burden of adjustment on the private sector. Much of the federal spending went to prop up state government spending on public-sector workers. That forced the private sector to bear more of the adjustment costs.

Many chide Austrian economists for not having a positive policy to cushion against the effects of the Great Recession. They did have a policy. It was to facilitate and not to impede the adjustments in asset markets.

First, do no harm. The macroeconomic response was largely harmful. In the second half of 2008, the Federal Reserve responded appropriately to provide more liquidity. After that, its various QEs were misbegotten. The economy was not suffering from a lack of liquidity, but the aftermath of a severe collapse in the prices of many assets. Financial institutions and other firms were insolvent, not illiquid. Additionally, the Federal Reserve policy of very low interest rates (negative in real terms) distorts capital allocation and creates new malinvestments.

Institutional reform?6

Since the financial crisis, the entire monetary and financial system has come under increased scrutiny and criticism.7 Relative to the recent past, the prospects for serious discussion of monetary reform are comparatively bright.

When discussing alternative reform proposals, the most basic distinction is between a regime of discretionary monetary policy and one governed by rules. It is difficult to conceive of a regime of pure discretion in which the monetary authority followed no rules or regularities in their actions. It would be a regime of pure randomness.

Axel Leijonhufvud (1984, p. 23) proposed viewing the modern fiat money regime as “a random-walk monetary standard.” David Fand, (1989, p. 325), elaborating on Leijonhufvud’s standard, said of the Federal Open Market Committee’s decision-making process: “[T]he only rule governing this process is that, at each point in time, those who are responsible for monetary policy choose the convenient and expedient thing to do.” Fand’s is a minimalist concept of rule-following behavior, and it is not unreasonable to designate such a regime as one of discretion.

The 100-year history of Federal Reserve policy is not an attractive one.8 Most studies of it start by writing off the Great Depression. The two wartime experiences are treated as exceptional periods (with justification). Periods of monetary stability get down to a relatively few years in the 1920s, the post-Accord period in the 1950s, and the Great Moderation in the mid-1980s to the mid-2000s. In each period, the Fed was rule-bound, though the rules differed – in the 1920s, the Fed was governed by the modified gold standard; in the 1950s there was a fiscal rule of balanced budgets (after the Korean War), imposed by President Dwight Eisenhower, a deficit hawk; and in the Great Moderation the Fed appeared to be following what is now called the Taylor Rule – a self-chosen and self-enforced rule.

It is conventional for the Federal Reserve’s good performance to be attributed to the Treasury Accord of 1951 and the central bank’s newly achieved independence from the Treasury. Cargill and O’Driscoll (2013, pp. 419–20) argue that the decade of the 1950s does not provide evidence that the Federal Reserve was independent, or that independent central banks provided superior inflation performance. Any central banker would have had a relatively easy job with the “Eisenhower Rule.” Once Eisenhower left office, the long-time Federal Reserve chairman of that era, William McChesney Martin, was willing to accommodate Kennedy-Johnson fiscal activism, and inflation ensued.

The brief periods of superior Federal Reserve performance support the findings of rule-based models. Moreover, the three episodes suggest that there may be a variety of rules consistent with monetary stability: a gold or commodity standard, a fiscal rule, and a modified monetarist rule. What is important is that a viable rule was in place. In each case, the rule constrained central bank policy-makers and helped insulate them from political pressures.9

Rules enable central banks to operate in a way that may be described as independent. As Adam Smith and the classical economists observed, it is the natural tendency of governments to spend in excess of revenues. Good rules help a central bank resist political pressures to inflate to pay for spending. Absence of a rule does not enhance, but rather erodes central bank independence (Cargill and O’Driscoll, 2013).

Public choice arguments are complemented by informational arguments. These were at the heart of the monetary work of both Milton Friedman and F. A. Hayek. They both argued that there are fundamental informational problems that render discretionary monetary policy impossible. Neither suggested that monetary policy actions had no effects. Quite the opposite. Both men believed that money had powerful impacts on the economy. But both argued we do not have sufficient information about the structure of the economy and agents’ expectations to improve economic outcomes in a systematic way. Friedman (1961, 1968) summarized these arguments most cogently. A brief quotation from an early monetary work of Hayek anticipates Friedman’s later, more thorough statement of the information problem. According to Hayek (1966, p. 23),

The one thing of which we must be painfully aware at the present time … is how little we really know of the forces which we are trying to influence by deliberate management; so little indeed that it must remain an open question whether we would try if we knew more.

We suggest, then, that the economic and financial crisis should lead to a reconsideration of risk analysis. The concept of Knightian uncertainty would help explain the extraordinary events in financial markets. Austrian monetary theory correctly characterized the credit-fueled housing boom, the accumulation of malinvestments, and the character of the panic and financial bust. The private sector, especially financial firms and households, experienced a collapse in asset prices and the necessity of deleveraging.

Finally, the time is ripe for consideration of monetary reform. The monetary regime is one of discretion, unconstrained by any rule except that of political expediency. Federal Reserve officials and monetary economists trumpet central bank independence. Instead, the central bank has become an enabler of fiscal excess. It is de facto once again bound by Treasury policy. It is back to the pre-1951 Accord era.

II. Challenge and opportunity of behavioral economics

Developments in behavioral economics over the past 30 years have provided both opportunities and challenges for Austrian economics. Behavioral economics is a curious mix of standard neoclassical economics and a fundamental critique of that economics. On the one hand, behavioral economics would be nowhere without standard economics. The research agenda seems to be to show why individuals do not behave in the way that standard models allegedly predict. In particular, behavioralists say people do not satisfy the standard rationality axioms for choice. These include a complete preference ordering that is consistent or stable over time, as well as transitive throughout the ordering. Experiments find that the violation of these axioms is ubiquitous. On the other hand, they say that people ought to satisfy these axioms (Berg and Gigerenzer, 2010). The axioms define rational behavior. Behavioral economists accept the normativity of the standard conception of rationality. Indeed, their policy prescriptions involve various degrees of incentivizing people toward rational behavior as it has been formally defined.

It is important to note, however, that in the historical development of the rationality axioms, the primary motivation of economists was not to show that following these axioms was a welfare-imperative for the individual. They were developed mainly to place utility function analysis, both under conditions of certainty and uncertainty, on a very general and abstract foundation. This was an effort to produce mathematical rigor rather than faithfulness to reality. They were not trying to isolate essential features of real individuals who, by some consequentialist standard, behaved correctly. Yet behavioral economists and many standard economists treat these analytical, constitutive norms as if they were prescriptions for well-being enhancing behavior.

In sharp contrast, the Austrian view of rationality has traditionally been of a minimalist sort. For example, Ludwig von Mises considers rationality to be synonymous with “human action” which is simply “purposeful behavior” (Mises 1966, p. 11). For our purposes, the details of Mises’ view are not important. What is important is that the Austrian conception opens the door to a pragmatic view of rationality. The individual’s purpose is to achieve his or her goals. The individual is interested in what works in the relevant context.

The challenge for Austrians is to contrast the standard and behavioral conception of rationality with the pragmatic (“praxeological”) view and to show the superiority of the pragmatic. The opportunity for Austrians is to encourage and participate in work that emphasizes the ecological rationality of behavior (Gigerenzer, 2008; Smith, 2008). Gerd Gigerenzer has developed an approach that conceptualizes heuristics as cost-saving methods of solving problems that are often superior to the application of formal systems of rational thought in the specific context in which individuals find themselves. Vernon Smith has emphasized the institutional structures that have grown up in society which produce results that are superior to those that isolated individuals could produce. For example, certain types of auction markets can produce results consistent with competitive equilibrium even where the agents are not individually well-informed.

Closely related to the concept of pragmatic rationality is attention to the meaning of problem situations to the agents themselves rather than to economists or other analysts. Before we can talk about the rationality of particular cases or types of behavior we must understand what problem the agent is attempting to solve. The importance of interpretation has been a key element in the subjectivist form of analysis. It is quite evident in all the writings of the earlier Austrian economists, especially Carl Menger, Friedrich Wieser and Eugen von Böhm-Bawerk. The characteristics of subjectivism were, however, most clearly elaborated in Hayek (1955). In Hayek’s analysis it is clear that before one can assess the conformity of individual decisions with rules it is important to understand the decisions subjectively:

So far as human actions are concerned the things are what the acting people think they are. … [T]he objects of economic activity cannot be defined in objective terms but only with reference to a human purpose … Unless we can understand what the acting people mean by their actions any attempt to explain them, i.e., to subsume them under rules which connect similar situations with similar actions, are [sic] bound to fail.

(Hayek, 1955, pp. 27, 31)

A convenient and much-discussed example in the behavioral literature will illustrate both the challenge and the opportunity. It is known as the “Linda problem” (Tversky and Kahneman, 1983). Experimental subjects were given the following description of a hypothetical Linda: “Linda is 31 years old, single, outspoken and very bright. She majored in philosophy. As a student, she was deeply concerned with issues of discrimination and social justice, and also participated in anti-nuclear demonstrations.” They were then asked to rank several propositions with respect to “probability” including the following three: Linda is active in the feminist movement (A); Linda is a bank teller (B); Linda is a bank teller and active in the feminist movement (A&B). Some 85 percent of subjects, including statistically sophisticated ones, rank A&B over B. This is considered an incorrect answer because the conjunction (A&B) is a narrower class than B. The class of bank tellers contains the class of bank tellers who are active in the feminist movement. So even if Linda is a bank teller active in the feminist movement she is also a bank teller. Thus the “correct” answer does not depend at all on the description provided of Linda.

An obvious question we should ask is: why are the experimental subjects being asked this question? The standard answer is to discover whether they know how to apply elementary principles of the probability calculus and, if they do not, to suggest an alternative explanation for their “deficient” behavior. The explanation most often given is that subjects are prone to a “representativeness bias.” The description of Linda is representative of a feminist in many people’s eyes and thus they choose “bank teller active in the feminist movement” over “bank teller.” Subjects decide on the basis of a representativeness heuristic rather than on the basis of the rational principles of the probability calculus. Rationality, in this behavioral experiment, is equated with adherence to a particular formal system of thought.

We should note, however, that the experimenters here are not acting cooperatively. By not acting cooperatively we mean that they are not satisfying ordinary conversational norms and expectations (Grice, 1989). It is reasonable for the subjects to expect that the information they are being provided is relevant to the correct answer. And yet it is not supposed to be.

One way in which the description provided will be relevant is if the term “probability” – which has an extremely broad meaning in everyday life10 – is interpreted as the degree to which a hypothesis is supported by the evidence (Linda’s description). This is the approach taken by Isaac Levi (2004, pp. 25–35). Such an interpretation is quite reasonable as it makes sense of the fact that the subjects have been presented with a description of Linda. Which of the two hypotheses (A&B or simply B), Levi asks, is given additional support by the evidence – that is, relative to what a person would have thought without the description? Clearly: “Linda is a bank teller active in the feminist movement” is the correct answer on this interpretation. The experimental subjects’ “rationality” has been rescued!

If the subject looks at the problem in this way, then he or she has not interpreted the problem in the same way that the experimenters do. In a sense this is an obvious point for us. No Austrian would simply assume that there is no difference between the analyst’s perspective and the actor’s. Each agent (experimenter and subject) has a particular perspective growing out of the context of his action. The experimenter is bringing a certain theoretical perspective to the situation. The subject is bringing a pragmatic perspective based on the ordinary norms of conversational expectation and the types of problems solved in everyday life. The theoretical and pragmatic perspectives are not the same (Gigerenzer and Hug, 1992).

Thus the behavioral economist’s analysis of the rationality of agents is hobbled by two factors: first, the narrow limitation of rationality to adherence to a single kind of formal system – the probability calculus; second, the assumption that individuals see the world the way the economist-analyst sees it. Interestingly, they are each failings that the behavioral economist shares with the standard neoclassical economist. The only difference is that the behavioral economist believes that these biases against rationality are pervasive and significant while the standard view is that they are not.

Regardless of whether the Linda problem has valuably pointed to a foible in human reasoning, certain points are clear. The interpretation of the agent is important and the correct solution depends on that interpretation. Rationality for economics should not be thought of as consistency with a formal calculus of some sort. It is preeminently instrumental or pragmatic. This depends on the context as the agent sees it.

Another related area in which behavioral economists have created a stir is on the issue of whether logically equivalent framings of problems result in the same decisions. People may react differently, for example, to different descriptions that are logically equivalent (Kahneman, 2011, pp. 363–74). They may be more likely to take a medicine if it is described as having a 40 percent (p) success rate than if it is described as having a 60 percent (1-p) failure rate. If so, then the subjective interpretation of the frame determines the outcome. The inference drawn by behavioralists is that if the mere description affects a person’s choice then he or she could not have had determinate mental preferences. Therefore, actual choice does not reflect the improvement of welfare in terms of an underlying stable mental preference. This is interpreted as if the decision is, to a large degree, arbitrary.11

The problem for standard and behavioral economists is the same. They each ignore the broader context of human communication. Abstract logical criteria are not sufficient to understand behavior either descriptively or normatively. In general, logically equivalent statements used outside of logic classes or logic textbooks do not have the same semantic content. There will be “information leakage” from the selection of the particular frame, which, in turn, can be received by those who interpret the frame (Sher and McKenzie, 2006).

The act of selecting or interpreting a frame is part of the process by which the individual determines what is relevant to the decision at hand. Do the logically equivalent statements about success and failure of the medical treatment mentioned above each convey the same information – are they informationally equivalent? In normal everyday contexts it appears that they are not. McKenzie and Nelson (2003) show that people select and interpret the different logically equivalent formulations when they are implicitly comparing the result relative to a norm or expected result. The p-description is more likely when the framer is conveying that the survival data are better than might be expected; it may be better still since certain structural features in the world may have changed, or if there is reason to believe that, in the case at hand, the degree of belief in a successful result is greater than the statistical frequency.12 The selection of frame by one party is an informational message to the other party.

The study of human action and choice is not an exercise in applying abstract logical relations or identifying logical equivalences. Before the rationality of choice can enter the picture, both actors and analysts must attend to the meaning attached to decision, to the objects of choice, to the ways in which choice is conceived or presented. This is part of a broader process of rational decision-making derived from the social context in which individuals act.

Framing is preeminently part of the process of rationality, that is, part of the process by which agents set up a decision problem in the first place (Kirzner, 1973). At that point, and only relative to that point, can we assess the rationality of their behavior.

All of these themes are familiar to Austrians and to readers of The Economics of Time and Ignorance. They have been made more relevant than ever before by the debates, challenges and opportunities generated by behavioral economics.

Conclusions

Ideas among economists often change under the influence of external events and shifts in intellectual paradigms. Our purpose in this Introduction is to show how developments in these areas have made the message of our book more, not less, relevant to contemporary economic thought. We obviously have not examined in depth the ways in which Austrian ideas can now insinuate themselves in the broader intellectual discussion. That would require a different book. But as we emphasized in the last chapter, our purpose, then and now, is to encourage readers to add their own research projects to the time-and-ignorance agenda.

Notes

References

Berg, N. and Gigerenzer, G. (2010) “As-If Behavioral Economics: Neoclassical Economics in Disguise?” History of Economic Ideas 18: 133–66.

Cargill, T. F. and O’Driscoll, G. P. Jr. (2013) “Federal Reserve Independence: Myth or Reality?” Cato Journal 33: 417–35.

Chamlee-Wright, E. (2010) The Cultural and Political Economy of Recovery: Social Learning in a Post-Disaster Environment New York: Routledge.

Dowd, K., Hutchinson, M., Hinchliffe, J. M., and Ashby, S. (2011) “Capital Inadequacies: The Dismal Failure of the Basel Regime of Bank Capital Regulation.” Policy Analysis no. 681, Washington, DC: Cato Institute.

Fand, D. (1989) “From a Random-Walk Monetary Standard to a Monetary Constitution.” Cato Journal 9: 323–44.

Friedman, M. (1961) “The Lag in Effect of Monetary Policy.” Journal of Political Economy 69: 447–66.

Friedman, M. (1968) “The Role of Monetary Policy.” American Economic Review 58: 1–17.

Friedman, M. (2002 [1962]) Capitalism and Freedom Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Friedman, M. and Schwartz, A.J. (1963) A Monetary History of the United States: 1867–1960 Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Friedman, M. and Schwartz, A. J. (1971) A Monetary History of the United States, 1867–1960 Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Gigerenzer, G. (1994) “Why the Distinction between Single-Event Probabilities and Frequencies Is Important for Psychology (and vice versa).” In G. Wright and P. Ayton (eds.) Subjective Probability Chichester, UK: Wiley.

Gigerenzer, G. (2008) Rationality for Mortals: How People Cope with Uncertainty New York: Oxford University Press.

Gigerenzer, G. and Hug, K. (1992). “Domain-Specific Reasoning: Social Contracts, Cheating, and Perspective Change.” Cognition 43: 127–71.

Gigerenzer, G., Hertwig, R., van den Broek, E., Fasolo, B. and Katsikopoulos, K.V. (2005) “‘A 30% Chance of Rain Tomorrow’: How Does the Public Understand Probabilistic Weather Forecasts?” Risk Analysis 25: 623–9.

Gorton, G. B. (2010) Slapped by the Invisible Hand: The Panic of 2007 New York: Oxford University Press.

Grice, H. P. (1989) Studies in the Way of Words Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press.

Hayek, F. A. (1955) The Counter Revolution of Science Glencoe, Ill.: Free Press.

Hayek, F. A. (1966 [1933]) Monetary Theory and the Trade Cycle New York: Augustus M. Kelly.

Kahneman, D. (2011) Thinking, Fast and Slow New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

Kirzner, I. M. (1973) Competition and Entrepreneurship Chicago: University of Chicago.

Leijonhufvud, A. (1984) “Inflation and Economic Performance.” In B. Siegel (ed.) Money in Crisis Cambridge, Mass.: Ballinger for the Pacific Institute.

Leijonhufvud, A. (2009) “Out of the Corridor: Keynes and the Crisis.” Cambridge Journal of Economics 33: 741–57.

Levi, I. (2004) “Jaakko Hintikka.” Synthese 140: 37–41.

McKenzie, C. R. M., and Nelson, J. D. (2003) “What a Speaker’s Choice of Frame Reveals: Reference Points, Frame Selection, and Framing Effects.” Psychonomic Bulletin and Review 10: 596–602.

Mises, L. v. (1966 [1949]) Human Action: A Treatise on Economics (3rd ed.) New York: Henry Regnery & Co.

O’Driscoll, G. P. Jr. (2014) “The Case for Monetary Reform.” Cato Journal 34.

O’Driscoll, G. P. Jr., White, L. H., Sumner, S., and Jordan, J. L. (2013) “The Federal Reserve at 100.” Cato Unbound Washington, DC: Cato Institute.

Phelps, E. (2009) “Uncertainty Bedevils the Best System.” Financial Times, April 15.

Samples, J. (2010) “Lawless Policy: TARP as Congressional Failure.” Policy Analysis, no. 660. Washington, DC: Cato Institute.

Sher, S. and McKenzie, C. R. M. (2006) “Information Leakage from Logically Equivalent Frames.” Cognition 101: 467–94.

Smith, V. (2008) Rationality in Economics: Constructivist and Ecological Forms New York: Cambridge University Press.

Taylor, J. B. (2009) Getting Off Track: How Government Actions and Interventions Caused, Prolonged, and Worsened the Financial Crisis Stanford, Cal.: Hoover Institution Press.

Tversky, A. and Kahneman, D. (1983) “Extensional versus Intuitive Reasoning: The Conjunction Fallacy in Probability Judgment.” Psychological Review 90: 293–315.

Zywicki, T. (2011) “The Auto Bailout and the Rule of Law.” National Affairs 7: 66–80.