The commercial exploitation of children … is particularly egregious. Recognizing that children are not fully mature with regard to making informed decisions, we control the promotion of alcohol, firearms, and tobacco. Yet we assume that young children can rationally decide about food choices that have important health consequences, and we expose them to intense marketing of products that are largely devoid of nutritional value but replete with calories.

—WALTER WILLETT, HARVARD NUTRITION RESEARCHER1

Your brain sorts through thousands of images and sensations each minute. Memory discards most of this input but stores what gets through the filters.

Advertisers must compete with all else going on (what they refer to as clutter) just to get your attention, much less have their jingle or slogan stored away so you don’t forget. Let’s see how well the food companies do.

Take a moment to jot down which food is associated with the slogans listed below.

(a) Melts in your mouth, not in your hand

(b) Break me off a piece of that ________ bar

(c) It’s the real thing

(d) They’re magically delicious

(e) No one can eat just one

(f) The best part of waking up is _________ in your cup

(g) Silly rabbit, ________ are for kids

(h) He likes it! Hey, Mikey!

(i) We love to see you smile

(j) Have it your way

(k) M’m, M’m good

(l) They’re Grrrreat!

(m) I go cuckoo for ________

(n) Taste the rainbow

(o) Do the Dew

(p) Finger lickin’ good

(q) Obey your thirst

(r) Snap! Crackle! Pop!

(s) The other white meat

(t) Billions & billions served

Answers2

Advertising Age magazine listed the top 100 ad campaigns, jingles, slogans, and icons of the century. Coke, McDonald’s, and Pepsi were in the top fifteen campaigns of all time.3 Among the top ten jingles of the century were:

1. You deserve a break today (McDonald’s)

3. Pepsi Cola Hits the Spot (Pepsi)

4. M’m, M’m good (Campbell’s)

6. I wish I were an Oscar Meyer Wiener (Oscar Meyer)

9. It’s the real thing (Coca-Cola)

Food captured seven of the ten top advertising icons:

2. Ronald McDonald

3. The Green Giant

4. Betty Crocker

7. Aunt Jemima

9. Tony the Tiger

10. Elsie

Both the food industry and its critics can agree that massive money is spent on food advertising and that food slogans, jingles, and advertisements have become fixtures in American culture. But here the agreement stops.

Industry claims that advertising is only effective at moving people toward brands of products they will use anyway: a child might be tugged by General Mills to eat Count Chocula or by Kellogg to want Disney Buzz Blasts, by Pepsi to want Gatorade or by Coke to want Powerade. Such advertising, so the industry says, does not compel children to want sugared cereal or soft drinks more than they would otherwise.

On the other side are those who believe that images of unhealthy food are implanted in the American brain and that it defies common sense (and now research) to say that food advertising does not increase consumption.

The resolution of this argument is important. If the nation’s consumption of sugared cereals, soft drinks, and fast food is unaffected by advertising, getting stirred up about food advertising makes no sense. Who cares if a child eats Count Chocula rather than Lucky Charms? If the assumption is wrong, however, reining in food advertising becomes logical, with special protection afforded to those least capable of protecting themselves (children). About one-third of the $30 billion spent each year on food advertising is targeted at children.

Television is the leading means of persuasion for the food industry. The average American watches 1,567 hours per year, or 3-4 hours per day.6 America’s children spend more time watching television than doing anything but sleeping. At least 96 percent of American homes have one TV; 65 percent of eight- to eighteen-year-olds and 32 percent of two- to seven-year-olds have a TV in their bedroom. By age seventy, the average person has spent seven to ten years watching TV.

The Better Business Bureau noted that children watch the equivalent of a fifty-day “marathon” of television each year, most of which occurs on weekday afternoons and Saturday mornings, when parents may not be supervising.7 The Boston Globe reported that African American households watch 10.5 hours of TV daily (76 hours/week) versus 54 hours a week in other households. The National Assessment of Education Progress found that 34 percent of people with poor reading skills watched six hours or more of TV daily, compared to 6 percent of the best readers. And most of the children watching six hours or more were African American.8 One study found that 17 percent of children eleven months old or younger, 48 percent of those ages twelve to twenty-three months, and 41 percent of those ages twenty-four to thirty-five months watch more TV than recommended by the American Academy of Pediatrics. These early viewing habits persist into later childhood.9

Major networks show between 8.5 and 10.3 minutes of commercials per hour of programming, many for food.10 In 1997, food advertisers spent $1.4 billion to promote food on network television and $1.2 billion to promote restaurants and drive-ins. On syndicated television, food advertisers spent $369 million on ads for snacks and soft drinks, followed by $144 million on restaurants and drive-ins. Restaurants and drive-ins were the largest advertisers on local TV, spending $1.3 billion. Food stores and supermarkets ranked fifth, spending $336 million for local advertising.11

Some parts of the food industry are especially aggressive with advertising. The advertising budget for soft drinks in 1998 was $115.5 million, for popular candy bars it was $10-$50 million, and for McDonald’s the budget was more than $1 billion. Compare that with the National Cancer Institute’s $1 million budget for its 5 A Day campaign or the $1.5 million for the National Cholesterol Education Campaign of the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute.12 A UK-based magazine ranked McDonald’s the most prolific advertiser in the world in 1997.13

TV advertising is convincing. Forty-nine percent of American adults view television as the most authoritative advertising medium, followed by 24 percent for newspapers. Almost three-fourths vote television as the most exciting medium. Sixty-six percent find it the most persuasive, and 78 percent believe it to be the most influential.14

Critics of regulating food advertising say that parents can turn off the TV, but TV only begins the onslaught. Ads on billboards; product placements in movies; food logos in schools; splashy signs on vending machines; and ads on buses, taxis, and even police cars contribute to the blitz. Every child is exposed.

Children were identified as a separate market for advertisers in the 1960s.15 The concept developed quickly, and now there are conferences, books, and ad agencies all focused on children as consumers. Marketing handbooks encourage businesses to target children and provide strategies to “unlock the secrets to children’s hearts.”16 As a result, marketing to children has doubled since 1992.17

Targeting children is partly to develop the next generation of adult customers, but what children spend right here, right now is remarkable. American children ages five to fourteen spend $20 billion each year and influence the spending of about $200-$500 billion annually.18 Children ages four through twelve had access to $31.3 billion in 1999 from allowances, jobs, and gifts, and they spent 92 percent of it.19

The average American child sees 10,000 food advertisements each year, just on television. Children watching Saturday morning cartoons see a food commercial every five minutes. The vast majority are for sugared cereals, fast foods, soft drinks, sugary and salty snacks, and candy; few promote foods children should eat more frequently such as fruits and vegetables.21 Between 1976 and 1987, the ratio of high- to low-sugar ads increased from 5:1 to 12.5:1.

Researchers complained about advertisements for unhealthy food as early as 1973,22 but the situation has worsened. One study found only ten nutrition-related public service announcements versus 564 food advertisements during 52.5 hours of Saturday morning TV23

Companies offer meals with toys and characters to entice children. In one holiday season, three fast-food companies competed for children with major promotions. Burger King featured the Rugrats, McDonald’s had A Bug’s Life, and Taco Bell used the Taco Bell Chihuahua. When asked who would win, an analyst stated, “Maybe in the end, they all win. … I can easily see kids wanting stuff from all three promotions—and especially around the holidays, if the kids want it, it’s hard for parents to say no.”24

Keebler used aggressive marketing to make their Chips Deluxe brand the company’s top-rated cookie in 1997. Promotions included a Chips Deluxe “Create Your Own Cookie Contest” and the introduction of “Dude,” an animated character in Chips Deluxe ads to make the brand relevant to children. Revenues increased by 25 percent.25

Given the $30 billion per year spent on food advertising, we must assume it works and that people buy more of the advertised food. The core question, though, is whether advertising changes the overall diet, especially in children.

Children view television with less skepticism than adults and therefore are particularly vulnerable to advertising.27 Research with fifth- and sixth-graders showed that more than half believed every commercial they viewed in the study. Children have difficulty distinguishing between advertising and programming and before age eight do not understand that the intent of commercials is to sell a product.28

Advertisers employ many methods to get attention, but chief among them is the use of easily recognizable characters and cartoon figures. The hope is that children will transfer the emotional attachment they feel about a character to a product. A study of 229 preschoolers showed that even very young children recognize and remember brand logos.

In a study of children ages nine through eleven, 94 percent knew that Tony the Tiger sells cereal and 81 percent knew that frogs sell beer. Slogans were also well recognized; 80 percent knew the “What’s up Doc?” Bugs Bunny slogan, 73 percent recognized the “Bud-weiser” frogs’ slogan, and 57 percent the Tony the Tiger “They’re Grrrreat” slogan.30 Thirty percent of three-year-olds and 91.3 percent of six-year-olds were able to match Joe Camel to a cigarette.31 An experiment with eight-year-olds asked, “Who would you like to take you out for a treat?” Tony the Tiger and Ronald McDonald were more popular choices than the children’s parents.32

Figure 5.1 Banned

Ads also change attitudes. In children ages two through ten, a single exposure to an advertisement produces more favorable attitudes toward the product.33 Ten- to thirteen-year-olds who are aware of beer commercials hold more favorable beliefs about drinking, have greater knowledge of beer brands and slogans, and show increased intent to drink as adults.34 TV watching has been linked to unhealthy nutrition perceptions in fourth and fifth graders.35

Awareness and attitude changes notwithstanding, the ultimate test is whether advertising affects behavior. Poor eating practices are correlated clearly with the amount of TV a child watches. A study with three- to five-year-olds found that TV time is linked to the purchase-influencing attempts of the children at the grocery store. Cereal and candy are two of the most requested items and two of the most advertised foods.36 First graders watching ads for high-sugar foods choose more sugary foods, both advertised and nonadvertised.37

As discussed in Chapter 2, watching TV is linked to increased snacking and caloric intake and decreased nutrient quality among children. The number of hours of TV viewed each week is correlated with what children ask their parents to buy, what parents do buy, and calorie intake.38 Children whose families watch TV during mealtimes have poorer diets than those who do not.39 Although one study of tenth to twelth graders found no association between viewing commercials and snacking,40 other studies continue to find a relationship.

Figure 5.2 Embraced (Permission granted by the photographer, Evan Johnson.)

While generally consistent, these studies can only take us so far in understanding how food advertisements affect diet. There is only circumstantial evidence that the ads cause poor eating. It is possible that some third factor, say level of education or parents’ nutrition knowledge, drives both the amount of TV seen and the diet of a child. One could also argue that something about watching TV other than the food ads leads to weight problems, with physical inactivity the logical candidate. An interesting way to address these issues would be to compare children who watch commercial TV to those who spend the same amount of time watching videos or public TV. This would control for the effect of activity and would help isolate the effect of food ads. Some experts, however, believe the question has been answered—TV promotes increased consumption.41

We can conclude that more TV means more food ads, and with more ads comes deteriorating diet. It is hard to imagine that the barrage of ads children see from their earliest years does not create desire for the foods they see. Children should not be fair game for the food companies.

Partnerships have evolved between the food industry and companies involved in the fantasy and play world of children. Movie figures have been in fast-food children’s meals for many years, but the phenomenon is spreading far beyond. There are now dozens of food products associated with the most popular children’s television and movie characters.

A colleague told us of her four-year-old daughter at the supermarket seeing Betty Crocker’s Disney Princess Fruit Snacks with Cinderella, Snow White, and the Little Mermaid on the box.

Daughter:“I want that.”

Mother:“What is it?”

Daughter:“I don’t know.”

Such anecdotes underscore the obvious—that for these partnerships to be so pervasive, foods must help promote TV shows and movies, and the characters help sell food. The four-year-old child probably had faith that whatever was in the box would taste good (would be high in sugar, fat, or both).

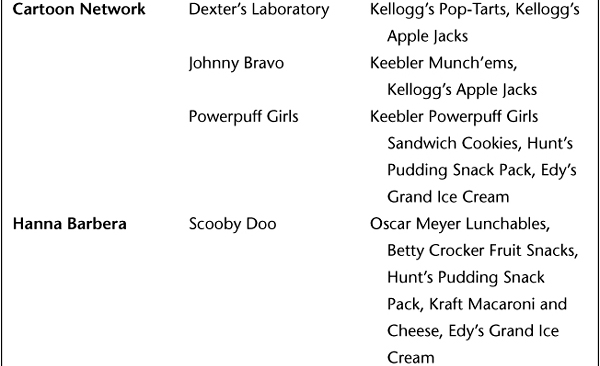

In order to get a snapshot of the TV/movie and food pairings, one of us (KB) made a field trip to the nearest supermarket with two expert observers (a boy age eight and girl age fourteen).45 We examined all food items and made note of each instance of a character/food pairing (see Figure 5.3).

Figure 5.3 Television and Movie Characters Used to Promote Food

The table does not include food products associated with sports stars and organizations (NASCAR paired with pudding, Kobe Bryant paired with Nutella), movie actors (Scorpion King characters paired with Reese’s Bars), bands (O-Town paired with Frosted Cheerios), or one food paired with others (Nestle Crunch in Yoplait yogurt, M&M’s in ice cream sandwiches).

Most items we found would not be on lists of foods children should be encouraged to eat. After finding these 59 products in a single store, it seems clear that selling unhealthy foods with TV and movie characters is common practice and that using them to sell healthy foods is rare.

Many companies (thirteen in our local tally) negotiate the rights for their characters to the food industry, but Nickelodeon and Disney appear to lead the way. Each owns characters immensely popular among children.

Disney has a long history of helping sell fast foods, sugared cereals, and more. Its clout, reach, reputation, and creativity are what make parents believe Disney can be trusted. You can take young children to Disney movies and count on them seeing reasonable content. This trust might be threatened as the public objects to food alliances.

Children’s meals at McDonald’s or Burger King often include Disney characters as toys, and characters are used to sell pudding, snack chips, fruit snacks, ice cream, and more. Disney has established a relationship with Kellogg’s in which prominent Disney characters become icons used to sell cereals. The cereal boxes have “Kellogg’s—Disney-Pixar” in bold letters across the top of the box, with the Tinkerbell character flying above. The Kellogg-Disney portfolio includes Buzz Blasts (with Buzz Lightyear the icon), Hunny Bs (Winnie the Pooh and other Pooh characters), and Magix (Mickey Mouse), all highly sweetened cereals. The Kellogg-Disney partnership is important to both companies:

“We’re excited about the possibilities with this alliance,” said Kellogg spokesman Neil Nyberg. Kellogg’s co-branded goods will be served at Disney’s theme parks and resorts as well as promoted through its entertainment properties, which include radio stations, film production companies, and television stations.

For Disney, it is an opportunity to partner with a company that connects with children and parents, said Andy Mooney, president of Disney Consumer Products, which licenses the Burbank, Calif-based company’s characters.

“Clearly in the case of cereal, Kellogg is a global leader in their category the same way Coca-Cola is a leader in carbonated beverages,” Mooney said.

Mooney said his goal is to put Disney products in front of consumers on a daily basis.47

The mating of Disney characters with food happens in a carefully choreographed way. For instance, the Buzz Lightyear character (from Toy Story) was in McDonald’s Happy Meals. Then the movie was released and Kellogg’s—Disney-Pixar placed Buzz Blasts cereal on supermarket shelves. McDonald’s helps promote the movie and its spin-off products like pajamas, toys, lunchboxes, and bedding, and Buzz draws kids to McDonald’s. Kellogg’s then gets a boost from both Disney and McDonald’s. Everyone wins.

A three-way partnership was established between Disney Interactive, General Mills, and EarthLink (an Internet provider).48 Netactive created a CD game to help Disney promote Toy Story 2. The CD provided three hours of free play and was packaged in five million boxes of Frosted Cheerios and Cinnamon Toast Crunch cereals. Consumers playing the game could then buy the software online for $9.99 or receive it free if signing on with EarthLink. General Mills had growth as high as 63 percent during this period, which was more than double the growth of Toy Story cereal without the premium. General Mills, through its subsidiary Betty Crocker, also pairs with Disney in selling fruit snacks.

It is common practice for companies to pay for their products to appear in movies and on television. Products sometimes appear by happenstance, but in many cases, money changes hands and products get featured. This practice began many years ago, but is now so common that there are more than 100 product placement agencies and even a professional organization to represent them, the Entertainment Resources Marketing Association (ERMA). ERMA notes:

The greatest home run in product placement since E.T. scarfed up a pack of Reese’s Pieces came with BMW’s launch of its Z3 roadster last fall. When the car became James Bond’s preferred ride in the 007flick Goldeneye, the hype and glitter surrounding this placement became an event unto itself, generating hundreds of millions of dollars worth of exposure worldwide. The deal won BMW and its marketing partners a Super Reggie as the top promotion of the year. Beyond the accolades and the press clips, though, the placement helped drive BMW’s business as discounts for the Z3 vanished and waiting lists stretched out for months.50

One leading firm, Feature This!, with offices in six countries, notes how powerful placement can be, especially when celebrity endorsements are implied: “The cost of celebrity endorsements is usually exorbitant and many celebrities refrain from such activities. However, product exposures act as implied celebrity endorsements.”51

The tobacco companies were early adopters of product placement. In 1980 Rogers & Cowan, a Beverly Hills public relations company representing RJR Tobacco Company, sent this memo to RJR:

The Cannonball Run—To be released by 20th Century Fox. Through special arrangements with producer Al Ruddy, we have arranged important visibility for several R.J. Reynolds products in the film. This comedy stars Burt Reynolds, Farrah Fawcett, Roger Moore, Dean Martin, Sammy Davis, Jr., Dom DeLuise, Bert Convey, Terry Bradshaw, Bianca Jagger, Mel Tillis, and others. In the film, there will be numerous scenes showing cigarette smoking in a most favorable light and in some of these scenes we will actually see one or more of our brands. Additionally, Burt Reynolds plays scenes wearing a Winston jacket and Winston racing cap.52

Similarly, food is featured prominently in movies and TV, perhaps by accident, but perhaps not. A few examples, featuring just one food company:

• Sleeper (1973). Woody Allen awakens from an operation to be 100 years in the future. Allen walks in front of McDonald’s.

• Bye, Bye Love (1995). Three divorced men struggle with custody and raising children. The movie begins with mother and father exchanging children at a neutral location, McDonald’s. McDonald’s is shown many times in the movie as parents exchange children.

• George of the Jungle (1997). George is transported from the jungle to San Francisco. He lands on top of a taxi with a McDonald’s placard and goes to a McDonald’s drive-thru. A McDonald’s representative was on location for the shooting to attend to the company’s interests.53

• The Flintstones (1994). The movie shows a prehistoric shopping center with a “Roc Donald’s.”

This just begins the list. An anti-drug soldier comes across a Quarter Pounder wrapper from McDonald’s in Clear and Present Danger with Harrison Ford, and Macaulay Culkin in Richie Rich has a McDonald’s in his house.

The latest advance is virtual placement. An article in Los Angeles Magazine explains how this happens.54 Products are inserted into program reruns as if they were there originally. For instance, Jerry Seinfeld might be eating cereal in an original episode but have a Cap’n Crunch box inserted electronically into the rerun. The food company is charged what a thirty-second commercial would cost.

You may also notice virtual advertisements on televised sporting events. A computer inserts what looks like a billboard on a stadium wall, scoreboard, and so on. While a pitcher peers at the catcher’s signal in the World Series, there to the left of the catcher and umpire is a prominent product sign created by the computer.

Marketing products to children is big business, with many people profiting. Most obvious is the food industry, but there are others including ad agencies and public relations firms who help promote the foods, the media who sell advertising space, consultants who establish deals between food companies and other enterprises (movies, schools, etc.), and, of course, all the places that sell food (supermarkets, convenience stores, drugstores, gas stations, schools, etc.). Add these together and you have powerful financial interests opposing change.

A number of organizations, publications, meetings, and marketing businesses exist to help companies sell products to children.

• Kidscreen magazine, in addition to covering children’s marketing in its articles, convenes conferences such as one in New York City on “Advertising and Promoting to Kids.”55

• Golden Marble Awards are given each year for the most effective advertising campaigns directed at children. Winners have included ads for Hostess snack cakes, Mountain Dew, Gatorade, Burger King, and McDonald’s.

• A group called Kid Power Xchange is “the ultimate knowledge resource for youth marketers.”56 It holds the Kid Power Food & Beverage Marketing Conference. Workshops have included “Excitement in the Beverage Aisle—Taking Disney’s Magic to the Grocery Store,” “From Supermarkets to Soccer Fields: Kids’ Wants, Moms’ Behavior,” and “Targeting Soft Drinks to Kids.”

• Selling to Kids magazine publishes articles such as “The Best In-School Marketing Campaign” and “The 3 P’s of Food and Beverage: Promotions, Premiums, and Partnerships,” saying things like “With kids spending about a third of every dollar on things they can put in their mouths, your product’s image and sales can benefit from associations with brands in this segment.”57

That these groups and activities exist is a sign that the business world, government leaders, and the general public believe that it is legitimate enterprise to sell products to children.

Take the Golden Marble Awards. On occasion these are given to companies who use marketing for good causes. For instance, a 2001 award was given to Campbell Mithun for an antismoking campaign. What is more common, though, is for a company such as Leo Burnett to win for a McDonald’s ad using Britney Spears. Leo Burnett then lists its Golden Marble Awards among its accomplishments in order to sell itself to potential clients and employees.59

Some people and organizations believe that children’s advertising is harmful and should not be permitted at all. In a position statement, the American Academy of Pediatrics declares that “Advertising directed toward children is inherently deceptive and exploits children under eight years of age.”61

Stop Commercial Exploitation of Children (SCEC), a coalition of many child advocacy organizations, believes that marketing to children is exploitive and harmful to the nation’s youth.62 SCEC notes that the United States regulates advertising to children less than most other democratic nations.

The Center for Media Education (CME, formerly Action for Children’s Television, ACT) was founded in 1991 as a national nonprofit organization to bring about federal change in children’s television. The organization has been active in testifying to the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) and in creating the 1992 Campaign for Kids’ TV that involved parent, education, and advocacy groups in the cause. In 1996, the CME was instrumental in persuading the FCC to require a minimum of three hours each week of educational children’s programming.63 The CME takes the approach that the media can be used for constructive causes and that political leaders should be urged to protect children from negative influences and harness the media to have positive impact.

The Center for Science in the Public Interest (CSPI) started an organization called “Kids Against Junk Foods” to raise health awareness among children. The CSPI has targeted major corporations in the fight to protect children. An example is the “Save Harry” campaign to protest Coke’s exclusive global marketing rights to the Harry Potter movie.64

When the country’s main pediatrics association, a broad coalition of organizations concerned with child welfare, an organization for media and children, a leading nutrition watchdog group, and a top medical journal65 conclude that advertising practices are deceptive, exploitative, and harmful to the health and well-being of our children, there is reason for the nation to take notice. Our nation takes strong offense at the exploitation and harm of children, but only recently has the nation begun to view food advertising in this way. The food industry is concerned and is fighting back.

In the 1970s, the food industry was threatened by the possibility that the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) would regulate children’s advertising. It fought off this threat in part by establishing its own self-policing group, the Children’s Advertising Review Unit (CARU). Founded in 1974, CARU reviews advertising directed at children less than twelve years of age, but it has no legal recourse and seeks change only through voluntary cooperation with advertisers when claims are found to be misleading, inaccurate, or inconsistent with CARU guidelines. CARU supporters, including M&M Mars, Inc., Nabisco Foods, Hershey Foods, General Mills, and Frito-Lay, Inc., pay a fee to belong to the organization.66

Whether CARU is having an impact is difficult to assess. Children are bombarded more than ever by advertisements to eat unhealthy food, so from this perspective CARU either is not working or has minimal effects. One could argue, we suppose, that the situation would be worse if CARU guidelines were not in place. One thing is certain—what is being done currently is insufficient.

Balancing the right of companies to market their products with the need to protect the public has always been tricky, but in some cases the government has taken decisive action—with tobacco, for example. This has not occurred with food. Two case studies illustrate this point.

Case Study 1. A physicians group in Australia, the Australian Divisions of General Practice, met with food manufacturers and asked for a ban on junk-food ads during afternoon television programming. Prior to the meeting, Robert Koltai, speaking for the Australian Association of National Advertisers, promised that his group and others would be aggressive in countering the perception that advertising contributes to poor diet.

What’s alarming about this sort of challenge to advertising is that it proceeds on the basis that no one has control any more over their own behavior. It’s nannyism, which says that as individuals or families we have no responsibility for what happens to us.67

Instead of working with medical authorities, the industry fights, using the familiar call for personal responsibility. Time will tell whether Australia enacts such a regulation, but denying and fighting, a failed strategy for the tobacco industry, is a clear approach being taken by some segments of the food industry.

Case Study 2. In 2002, Coke and Pepsi distributors met with Governor Angus King of Maine about a state-sponsored media campaign initiated a month earlier by the Bureau of Health.68 The “Enough Is Enough” campaign used radio and TV ads and letters to parents to warn young people about soft drinks.

The soft drink industry was represented by Dennis Bailey, owner of a Portland public relations firm and, conveniently, former press secretary to Gov. King. Also present at the meeting was Guy Johnson, from Johnson Nutrition Solutions in Kalamazoo, Michigan, who writes and testifies widely on behalf of the National Soft Drink Association.69 Testifying before the NewYork State Assembly on soft drinks in schools, Johnson had said, “There is no nutritional reason why soft drinks, water, teas, sports drinks, and juices should not be made available to students and faculty”.70 Bailey said, “We object to being singled out. There is no scientific evidence that soda consumption causes obesity, and these ads draw that link.”71

As Chapter 7 explains, there is scientific evidence linking soft drink consumption to childhood obesity. So, did Gov. King dismiss the self-serving lobbyists and use his influence for the state’s children? Not exactly. The Governor’s spokesperson announced that the “governor listens and understands” the soft drink lobbyists. The Bureau of Health reworked the campaign, with components scheduled to be used later (on increasing physical activity) being moved up.

The FTC regulates advertising in America, focusing largely on false advertising and misleading statements (in representation or omission of facts deemed to be material).72 The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) share jurisdiction over claims made by food manufacturers. The FTC primarily regulates food advertising, while the FDA regulates labeling. The FTC may issue a temporary restraining order or preliminary injunction for suspected violation of its regulation. The penalty for violation of FTC provisions is a fine of up to $5,000 and/or a prison term of up to six months. Repeat offenders face a fine limit of $10,000 and imprisonment for up to one year.73

Current policies are inadequate. We agree with groups such as the American Academy of Pediatrics that children are being exploited by advertising and that change is necessary. The industry is not policing itself and the government falls short. The public health ramifications of poor diet are enormous, so it is time to declare current policies inadequate and take action to defend the nation’s children.

One might expect that lessons learned from promoting unhealthy foods could be used to encourage consumption of better foods. If true, it would be wise to use this information to improve the nation’s diet.

Research shows that children can be persuaded to eat healthy foods and can be taught to differentiate between persuasion and information in commercials.74 One study found that children who watch public service announcements focusing on nutrition choose more vegetables, fruits, and other nutritious foods.75 In another study, positive comments by an adult observer, along with pro-nutrition messages and ads for foods without added sugar, reduced three-to six-year-olds’ selection of foods with added sugar.76 A Canadian study found that children ages five through eight picked more candy than fruit following a candy commercial, but showing fruit commercials or public service announcements while eliminating candy commercials encouraged children to choose fruit.77

Simple reduction of time at the television can be effective as well. Thomas Robinson at Stanford used a school-based intervention to reduce TV, video, and video game use among children. Robinson found a significant reduction in weight among children in the intervention group compared to controls, along with decreased TV time and frequency of meals eaten while watching television.78

Parents have the power to shape children’s TV viewing habits. One study showed that the most important factor related to a child’s TV watching habits was the attitude of parents.79 The American Academy of Pediatrics recommends limits on media exposure for children, skills to help children view TV critically, and discussion of media content with children.80

Studies have also shown that rules at home can modify physical activity and TV viewing. When television watching is made contingent on pedaling a stationary bicycle, for example, children exercise more and lose body fat.81

Michael Jacobson, Margo Wootan, Bonnie Liebman, and others at the Center for Science in the Public Interest (CSPI) have devoted years to educating the public and policy makers about key nutrition issues, attending to issues such as labeling, packaging, and advertising of foods. CSPI publishes an excellent newsletter called the Nutrition Action Healthletter (www.cspitnet.org).

CSPI also has developed a nutrition site for children (www.Smart-Mouth.org).82 Among its features is a character named Gus, whose Trust Gus quiz helps children learn about the food industry. For example, a child is asked whether the following statement is true or false: “Food companies encourage people to eat even if they’re not hungry.” The answer: “The more often you eat, the more money food companies make. Check out their ad slogans like ‘don’t just stand there, eat something’, ‘;crunch all you want, we’ll make more,’ or ‘once you pop, you can’t stop.’”

Sweden has been very active in lobbying within the European Union to ban television advertising to children. Making such an effort on a broad scale is a success by itself. If Sweden prevails and the European Union develops a ban, it could lead the way for other countries to do the same.

The Province of Quebec, Canada, enacted the Consumer Protection Act in 1978, which stated that “no person may make use of commercial advertising directed at persons under thirteen years of age.” To determine whether advertisements are aimed at children, officials consider the nature and intended use of the advertised goods, the content of the advertisement, and the time and place it is shown.83

A grassroots campaign in 2001 by Stop Commercial Exploitation of Children was mounted to encourage Scholastic, Inc. to withdraw its sponsorship of the Golden Marble Awards. Scholastic publishes the Harry Potter books and is the nation’s leading educational publisher. Scholastic withdrew its support, with CEO Richard Robinson saying, “We wanted to let you know that Scholastic will not be a sponsor this year for the Kidscreen Conference. We appreciate your recognition that Scholastic has a long tradition of providing high quality products and services to teachers, children, and parents.”84

Greece bans toy ads until 10 P.M., while Belgium prohibits commercials five minutes before, during, and five minutes after children’s programming. Norway and Sweden ban advertising directly to children under twelve.85

A number of steps are possible to protect children from commercial exploitation in general and food marketing in particular.

A Roper Poll found that 80 percent of adults believe that marketing and advertising exploit children by convincing them to buy things that are bad for them, and a marketing report found that 85 percent of adults believe that children’s TV should be free of commercials.86 Legislators, by yielding to pressure from the food industry, are out of step with public opinion. If a few courageous legislators can resist the pressure and start the nation thinking about banning children’s advertising, public support could swell. It has been done elsewhere in the world.

It is a national priority to reduce obesity in children, improve their diets, and encourage them to be active.87 Standing in the way is the tremendous imbalance of promotion for unhealthy versus healthy food. Parents want their children to be healthy, educators want their children to be alert, and national leaders want the next generation of Americans to be vital, energetic, and fit. The unlevel playing field makes this unlikely.

If the food industry prevails in the political arena and the heavy promotion of unhealthy food continues, the nation must mount an effort to counter it. This would require considerable resources, because what must be countered are years of persuasion and trillions of dollars spent by the industry to change attitudes and eating behaviors.

In the 1960s, the Fairness Doctrine from the FCC was interpreted in a way that mandated television stations to run antismoking spots if they ran commercials from tobacco companies. The antismoking ads worked. The tobacco industry decided it was not cost-effective to advertise on television any longer and voluntarily ceased TV advertising in implicit exchange for being permitted to advertise elsewhere.

The Fairness Doctrine has been repealed, but something similar applied to food advertising may be beneficial. Requiring advertisements for healthy foods or spots discouraging consumption of unhealthy foods may help counteract the effects of existing advertising. It would not make sense to confine the rule to advertising on television.

For pro-nutrition and physical activity messages to be powerful, compelling, engaging, and frequent enough to make a difference, funds will be necessary to generate and then disseminate material. Professional time might be available as pro bono work from advertising and public relations firms. Media outlets might also agree to use public service space for nutrition and activity programming. This may help, but would only be a start.

Generating funds to promote nutrition might be done in several ways. In Chapter 6 we recognize that schools may lose money if they cease the sales of snack foods and soft drinks. A way to replace this funding would be to enact a small state or national tax on soft drinks, snack foods, and fast foods, earmarking the money for schools. Revenue from such a tax might also create a “nutrition superfund” that would be used to support healthy eating campaigns for children.

Placing an assessment, fee, or tax on advertisements that occur for unhealthy foods would also be a way of supporting a nutrition superfund. Many states are using tobacco settlement money to establish antismoking campaigns, so there is a precedent for having an industry help counter the problems it creates. The food industry might be willing to pay now in hopes of avoiding paying a higher penalty later if held accountable for health damages.

The public has divided opinion on food taxes (see Chapter 9). More people support taxes if assured that the revenue will be used for a related, constructive purpose such as programs to promote healthy eating.88 Support is likely to grow as the public becomes more aware of obesity as a national and world crisis and sees that so many people are affected.

The Children’s Television Act of 1990 mandated that broadcasters are required to have instructional programming/children’s educational shows. Groups such as the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Center for Media Education note that the law’s intent is violated routinely.89 Among the problems are that monitoring is done only at the time of license renewal and that stations list public service announcements, short vignettes, and even cartoons as educational programming. Insuring that the educational environment on each station is consistent with the law’s intent could be an important step forward.

One possible means of discouraging unhealthy eating would be to encourage media companies, such as Disney, Nickelodeon, the Cartoon Network, and Hanna Barbera, to cease connections with unhealthy foods. Using popular characters to promote healthy foods should be encouraged.

Disney does not associate its characters with cigarettes, probably because the damage to its reputation would be too great and questions arise on legal liability for promoting damaging behavior.

We cannot say that Buzz Blasts and Cinnamon Toast Crunch are the same as cigarettes. Cigarettes are illegal to sell to minors; the cereals are legal. Nicotine is an addictive drug, but whether foods can be addictive is not yet clear. Yet, a common principle might apply. If Disney helps increase sales of unhealthy foods, and children then increase consumption, can the case be made that Disney is harming the children? If parents begin to see things this way, Disney’s reputation will suffer.

A company such as Disney might stage a public relations coup by announcing its products will only be used to promote healthy foods. The benefit could be considerable, and other companies might be forced to follow.

The food industry, being the powerful economic force it is, can afford even the highest paid celebrities to endorse its products. Michael Jordan for McDonald’s, Shaquille O’Neal for Burger King, and Britney Spears for Pepsi are examples. Perhaps there is a way to harness their visibility and power in the service of improving diet.

Some Celebrities Endorsing Fast Foods and Soft Drinks

Both carrot and stick approaches may help. Celebrities would not endorse a product, no matter how great the reward, if public outrage were the consequence and future endorsements would be compromised. Hence, it is unlikely that Michael Jordan would promote Marlboro or that Britney Spears would promote Camel. If public sentiment turned against celebrities who endorse certain foods, the celebrities might take their endorsements elsewhere.

Some celebrities are civic-minded and embrace a wide array of social causes. Examples are soccer stars Mia Hamm and Kristine Lilly working with Safeway Supermarkets on the Eat Like a Champion program. If more such people take on healthy eating (or childhood obesity prevention) as their favored cause and then entice their celebrity peers to join in, tremendous change might be possible. These efforts would probably be seen quite favorably by the public, making such celebrities even more valuable in the endorsement marketplace.

The food industry claims that parents must take more responsibility if children are to develop healthier eating patterns. So fine, what would they suggest be done? Create massive education programs for parents? Design advertising campaigns to provide parents with the skills to work with their children? Devise penalties for parents who do not comply? Parental responsibility sounds good, but does not lead to helpful action.

Our nation has created an environment that makes it much too hard for parents to raise children who eat well and are active. Parents are subject to the toxic environment themselves, and even those who resist find it difficult to shield their children. Helping parents do their job is good policy.

Any means possible should be explored to assist parents. Websites, books, videotapes, and the like might be useful if they convey good information, can be distributed widely, get used, and affect the behavior of both parents and children. Creative programs through groups such as parent-teacher organizations might be helpful. Prenatal counseling for expectant mothers might work. There are many ideas to explore, most of them untested. They should be pursued, but we emphasize again that this can only be part of the solution.

Some schools have media literacy programs designed to help children become educated consumers, identify themes used to sell products, and resist being exploited. Smoking prevention programs have used this approach for years to show children how tobacco companies glamorize smoking.

Food also is important to target in media literacy programs. How food is advertised, product placements in movies, and even how schools deal with foods (vending machines, fund-raising events, etc.) could all be subject to analysis. As long as children are exposed to food advertising, they deserve education that allows them to place what they hear in the context of good health.

Advertising aimed at children is powerful in presentation, overwhelming in amount, and pernicious in outcome. Many children do not recognize the purpose of advertising and cannot separate advertising from programming.90 The Flintstones, for example, are TV and movie characters, but are also toys, vitamins, and cereals. Children find advertisements fantastically engaging because of fast-paced animation, clever story lines, and the use of captivating characters.

Groups with a strong interest in protecting children call for a ban on children’s advertising. The food industry opposes any change. For the sake of public health, for the common good, and for the welfare of our children, which side deserves your support?91