MANY READERS OF THIS BOOK WILL BE LOOKING INTO THE DISCIPLINE OF PROCESS IMPROVEMENT FOR the first time. But even if this area is new to them, most readers should be pretty much experts in more than one realm of information technology, perhaps programming, project management, or quality control; maybe architecture, design, or implementation; or, still yet, management, strategic planning, or performance analysis. Those kinds of backgrounds are invaluable when it comes to understanding the roles process improvement can play in organizational success. And they are essential for making the case for process improvement.

In fact, if you are what might be called the "typical" reader of this book, you may well understand more about the potential for process in your organization than most. The reason is simple. Process improvement is about improving the way the organization works. When it comes to that work, you're a pro.

Process is not (or should not be) about adopting new "things" blindly and then hoping that those things do whatever it is they're supposed to do. It should not be a series of new practices that represent what the "industry" says you should be doing. That is the antithesis of the process improvement philosophy. Process is about taking your approach to work and formalizing it into a program others can follow.

At its heart, process improvement is about four basic activities:

Looking at what you do

Focusing in on the things you do well (or want to do well)

Setting tools in place to help everyone do it similarly well

Keeping an eye open for ways to make that approach better over time

Those four steps are about as basic as you can get, but they bring me to an important point. Your expertise as a programmer, a manager, an analyst—these are all keys to the success of your organization's process improvement efforts. Your knowledge, experience, and insight should be the crucial components that will form the foundation of your improvement program. Without those, the program has nothing to stand on. And in their absence, even the most recognized of programs—like ISO 9001, CMMI, and Six Sigma—are just words on paper.

Those who do not seek to take advantage of what the organization already does well (its habits, knowledge, experience, and insight)—those people who prefer to wipe the slate clean—are missing a critical element to process improvement success.

Given that, I can now take a first step toward making the case for process in any technology organization. And the first point toward that goal is that you are the process.

In a book like this, it can be tempting to focus solely on what's wrong with the technology industry. After all, there are lots of tools we can use to make IT more effective. So why not point out all the holes that need to be filled? Any serious observer would agree that there are lots of things wrong with how we structure, manage, and execute IT in this country. Plenty. But in my view, that's looking at bent nails. It's handy, but it doesn't tell you much that's helpful.

A better view—the more informative view—is to focus on what the industry does right, to remember that American IT is a story of unparalleled success. In the span of only 30 years or so, it has achieved a level of saturation and sophistication no other industry in history can match. In fact, the main reason we are able to spot so many issues with IT is because of its runaway success. It's taken off in all directions. Look at these 2005 numbers:

Global IT industry spending: $1.3 trillion

Revenue of the U.S. Software 500: $311 billion

Number of electronic cash cards in circulation: 40+ million

Number of MRI scans: 20+ million

Dollar volume of online shopping: $38.3 billion

Number of global Internet users: 1,022,863,307

Number of wireless cell phone subscribers: 194,500,000

Number of iPods in use: 10+ million

Number of cities that went berserk at 12:01 a.m., January 1, 2000: 0

Number of emails you really didn't get that your cohorts insist they sent you: _____

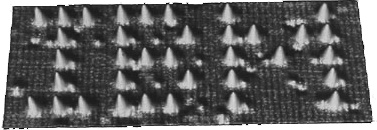

And if a picture is worth a thousand statistics, Figure 2-1 is a great picture for you.

Figure 2-1. Technology is an unparalleled American success story. Not only are cell phones, email, and laptops de facto ways of life, IBM scientists have been able to harness the attractive properties of atoms to line them up in an impressive, albeit tiny, billboard.

Figure 2-1 is not a promotion for International Business Machines. It's a picture of the result IBM scientists got when they trained a bunch of atoms to line up in a row. And not only were they able to get them to line up, they were able to build a camera sensitive enough to take a picture of it. So any way you look at it, the success story is there.

The idea behind process improvement then is to capitalize on that success, to institutionalize as much if it as we can.

In the previous section, I mentioned that a good first step in making the case for process is to remember that you are the process. Here's what I mean by that. Most IT professionals know what they are doing. They follow a general routine when they work. They have a process, even if it's a personal process.

The real issue then, the Big Issue, is not about personal competence; the talent pool in American IT is pretty competent. The issue is more about coordination, consistency, synchronicity, and predictability within and across groups. An organization is not an individual. So for an organization to operate efficiently, it helps for the groups that make up the organization to work along similar lines, to approach the issues of business in a consistent way. When the organization can do this regularly and predictably, it can synchronize its energies in a focused way. Not only that, it can now begin to observe the way it works so that it can improve the way it works.