An adaptable body of knowledge

Key points

■ What a project is and isn’t

■ Four interdependent project constraints

■ Defining project management

■ Comparing management and leadership

■ Delegating by degrees

■ Previewing four popular project management methodologies

■ Navigating the project management life-cycle

■ Factors behind project success and failure

■ The Project Management Body of Knowledge (PMBOK)® knowledge areas

In practice

Why, these days, is nearly everyone working on one or more projects? Everything we do appears to be a project of one sort or another. People aren’t simply working on tasks, files, activities or just ‘work stuff’ anymore—they are all, increasingly, on things called ‘projects’ for some reason.

Job advertisements are regularly populated with project management positions, while position descriptions are quickly being rewritten (sadly, not always well, despite the intent) with more of a project management focus to them. Business and industry are rushing to develop project management methodologies, processes, templates and software aligned to things called PMBOK®, PRINCE2®, Agile, Project PRACTITIONER (my own methodology), Microsoft Project, Primavera, along with a raft of other popular methodologies and tools. Academic qualifications, industry certification and public training in project management are increasingly in high demand.

Why the interest, why the focus, why the growing preoccupation with things loosely (and often incorrectly) called projects? Why is it that all this work will be (allegedly) better planned and managed with (allegedly) better outcomes merely by re-labelling it a project? Why is it that people believe everyone will become more committed and motivated to do the work because it is now called a project?

At the same time, look at what project work offers the organisation and the individual: strategic justification, executive mandate, operational prioritisation, not to mention a phased, controlled and approved evolution of performance, output and, one would hope, outcome. For the individual, it provides an opportunity to complete challenging work, to work with and or manage diverse stakeholders while also being part of a change initiative impacting the business. Perhaps the true question should be: Are they really projects at all? Further, having made this distinction, what actions does this then trigger? What benefits will be identified and measured? What deliverables will be planned, managed and handed over? How do organisations then begin to balance both these strategic initiatives with the constantly changing and competing operational priorities?

Chapter overview

Project management means different things to different people. For some, it represents a growing body of global knowledge, methodologies and best practice; for others, it is a borrowed set of methods, techniques, tools and tips modelled from the cornerstones of professional disciplines of accounting, risk, finance, human resources, total quality management, or industry and business, and/or the government with its policy, regulatory and compliance frameworks.

Are projects strategic initiatives thought up by boards, CEOs and executive management? Are they initiatives that will drive the organisation forward in response to the challenges of global competition, market pressure, tight deadlines, limited budgets, contractual conditions or a heightened need for compliance, transparency and accountability? Or are they workplace priorities populated in the operational plans of the organisation? Clearly, projects are no longer the sole domain of construction, engineering and other capital works infrastructure projects. Projects have literally flooded into management, customer service, hospitality, sales, marketing, IT, operations, finance, legal, healthcare, banking, community services, economics, sport, real estate, logistics, education, manufacturing, tourism, aviation, insurance and administration, to cite just a few ‘growth’ areas across the private, public and not-for-profit sectors.

Should we embrace particular methodologies: the Project Management Body of Knowledge (PMBOK), PRINCE2 (projects in a controlled environment), Agile, Project PRACTITIONER (my proprietary methodology), or the myriad other options and solutions actively promoted to respond to the differing degrees of uncertainty, complexity, risk and value? Or does the solution rest with a raft of technical, people and conceptual management skills that will underpin the success of the project? Some projects will range from the ambitious to the mundane, from those sired and protected by ‘sacred cows’ to those that are underfunded, from projects that never should have been approved in the first place and those that should have had the ‘plug’ pulled on them a long time ago (if only the brave would step up!) to projects with unlimited funding (yes, unlimited funding still does exist in some commercial and government corridors—perhaps you know it as contingency funding). Some projects will require enormous resources, while others need only one or two people at most. Some projects will be political hot potatoes, attracting considerable publicity and controversy, while others will barely appear on the public radar. Some will have organisation-wide impacts; some will be driven by markets and competitors; others will be generated by external regulatory authorities demanding compliance. Some will be risky, some complex, others perhaps straightforward and still others perhaps mediocre in design, execution and management.

In recent times, the evolution of projects has increased exponentially to the point where the discipline, methods and tools behind projects (and their management) have reached giddy heights of application, sophistication and popularity. What is driving this modern-day development and interest in projects? Is it due to:

■ the constant cycle of change within which business operates

■ time-poor business driven by tight (sometimes impossible) deadlines

■ advances in technology

■ the increasing influence of market pressures

■ global competition and the need to remain competitive

■ greater rates of (financial) return required

■ higher degrees of transparency, accountability and consistency

■ an increased interest in measured outcomes (benefits accruing from the project)

■ increased attention on legal and contractual obligations

■ the need to deliver products or services meeting benchmarks, quality assurance or best-practice guidelines

■ greater emphasis on businesses producing cost-effective solutions?

Perhaps the answer can be found in each of the points cited above, and the reason should be obvious. Projects have transformation at their heart as they create and deliver change of one type or another—small, easy, large, complex and over time—that must be managed effectively if the project is to succeed. In other words, projects provide the structure, the framework, the process—the perfect vehicle if you like—within which a change process is created and managed—however that change was initiated (a point that will be discussed in detail in later sections of this chapter). This is not to argue, though, that every change activity is in fact always a project.

However, irrespective of the known (and at times unknown) drivers and constraints behind each project, the project organisation will need to be clear about whether they are undertaking operational work (business as usual [BAU]) or strategic project work (change). Think about this crucial distinction for a moment because which would you do first: everyday operational routine work or time-specific project work?

Organisations are rapidly becoming focused on a number of critical issues driving their continued success:

■ the timing of decisions

■ the costs driving the decisions

■ the impact that change will have on these decisions.

To deal with these issues, project management has grown both in academic stature and commercial acceptance as a technique, method or tool for successfully dealing with time-, cost- and change-driven decisions and their impacts. It is the perfect tool to deal with these issues. So the obvious question now is: What is project management? Let’s start with a simple explanation. Think about any ‘apparent’ project (big or small) with which you are involved, with reference to the following:

■ the work required to be completed (scope)

■ who would be doing that work (resources)

■ the cost of the work being performed (cost)

■ how much time it would take to complete the work (time).

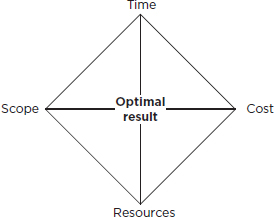

Now we can begin to bring our initial thoughts together. Project management in its rawest form essentially involves bringing together two over-arching and disparate (and at times conflicting) pieces of information—scope and resources—both of which have implications for costs and schedule. Put simply, something has to be done by someone within the constraints of time and budget. In other words, by combining all four, project management can be defined quite simply in terms of scope, resources, cost and time. Collectively, they represent the fundamental boundaries of the project (and ‘boundaries’ is a really great word that you will come to appreciate in all your projects), with each one intertwined tightly to the other three. That is, collectively they determine and communicate the project’s configuration at any point in time as reflected in Figure 1.1. This point will be expanded on later in this chapter.

Figure 1.1 Getting the equilibrium

The scope: More than just the work required

All projects involve delivering something (often referred to as an ‘output’, ‘outcome’, ‘benefit’, ‘asset’, ‘deliverable’ or ‘solution’) to someone (often referred to as the ‘client’, ‘sponsor’ or perhaps ‘business owner’). To achieve this ‘something’, a range of work first needs to be identified and then performed. But (and it is a big but), consider some of the additional information you need before you ‘go live’ on the project:

■ Will all this work be performed simultaneously or will some follow earlier completed work?

■ What other projects and/or work will impact on this work?

■ How long will each component of work take (commonly referred to as effort, sometimes mistakenly as duration or elapsed time)?

■ How accurate will these estimates be and how will this be communicated?

■ What impact will this work have on the planning, execution, management and completion activities of the project?

■ Can all the required work easily and correctly be identified, resourced and scheduled?

■ What risk factors might impact on the start or finish of the scheduled work?

■ Does the completed work comply with the required specification or standard?

The resources: More than just the team

Let’s now bring in the remaining component of our early definition of project management: the resources. A considerable amount of resource information is required concerning the work needed to complete the project. Again, consider the following to start with:

■ Exactly what resources are required? (Remember that the word ‘resources’ in a project management sense is not limited to the subject-matter experts (SMEs) and other skilled people. Equipment, meeting rooms, vehicles, laptops, funding, materials, reference manuals, intellectual property and even a high-speed internet connection are all examples of project resources.)

■ Are these resources available (not to mentioned motivated) to be assigned to the project tasks?

■ Have these resources got the required skills, authority and power (if people), and the right technical features (if materials)?

■ Do any of the human resources need training and development in particular skills?

■ How much do these resources cost, and who will bear these costs—existing functional overheads or the project cost centre?

■ Are there any substitute resources available if and when required?

■ How will competing functional (operational) and project work conflicts be managed and by whom?

■ What will indicate resource performance and achievement once the project starts?

■ Will risk be a factor in assigning and tracking the performance of these resources?

■ What impact will these resources collectively have on the planning, execution, management and completion activities of the project?

Going back to where this section started, project management essentially involves bringing together two components: work and resources. While we now know that work and resource information can contain myriad subsets and certain challenges, it still provides a valid and defensible starting point in understanding (and practising) project management. It does this by ‘chunking’ (or ‘limiting’, if you prefer) the underlying information and ultimate decision-making required by the project. The work must get done—and it must get done by someone (or something).

This is not to say that we should ignore other project considerations and issues, including stakeholders, risk, procurement, quality and communications (these will be explained in greater detail in later sections). Rather, it is an attempt to give the creation and management of projects a simple initial structure that enables senior management, project managers, teams and other internal/external stakeholders to ‘sign on’ to an immediate appreciation and understanding of two of the critical success factors underlying the key stages of the project’s evolution—creation, planning, execution and completion (often referred to as the ‘project life-cycle’).

Let’s now ‘beef up’ our tentative (and changing) definition of project management. To achieve this, we will briefly examine the words ‘project’ and ‘management’ separately, then bring them together into a couple of meaningful definitions and explanations.

To some people, projects are a little like a puzzle—too many pieces and not enough clues as to where they all fit in, how they interact and interrelate and who is responsible for piecing it all together. A project should be able to be defined in terms of a number of generally accepted criteria, which collectively distinguish it from an everyday activity performed by an individual or organisation. The criteria in Table 1.1 should be used as an illustrative guide.

So now you know what a project is (and, more importantly, isn’t): a sequence of tasks with and without dependencies that deliver on the client’s expectations within an agreed timeframe and budget. Sadly, far too many people rush to use the ‘project’ word for pretty much everything they do, while at the same time failing to implement the vast array of knowledge, skills, techniques and tools offered by projects.

Identifying the project boundaries

Much has already been said about project variables (often called constraints). They are the key criteria discussed above for identifying the essential differences between projects (in the true sense of the word) and recycled activities. Each variable is examined in greater detail in Table 1.2.

Table 1.1 Essential characteristics of a project

| Criteria | Explanation |

|---|---|

| Scope | The work performed on a project will not be completed ‘on a whim’. It will comply with a standard, a performance measure or a benchmark of some kind that explicitly defines and clarifies the exact nature of the work to be performed. |

| Cost | In most projects, cost is a finite resource. While contingent funding (in case the estimates fall short of true costs) should be available, the greater majority of projects will be constrained by funding (believed to be adequate). |

| Stakeholders | All projects are owned by their ultimate client, business owner or sponsor (the party to which the final deliverable is handed over) and all the other parties who either contribute to or are impacted by the project (e.g. staff, contractors, professional advisers, management, suppliers). |

| Resources | Projects require a pool of resources to achieve agreed deliverables. These could include any of the following: people, materials, equipment, facilities, tools, information, systems, policies, procedures, techniques, finances and knowledge, among others. These resources are often deployed on other projects and/or their normal work duties, which brings another degree of complexity and management to the project. |

| Time | Projects (must) have target start and finish dates that define (and constrain) the project window. That is, the project has a finite lifespan that is monitored, reported and (in many cases) amended. |

| Dependencies | All the required work will probably not be performed at the same time. Some work will precede other work, some might occur concurrently, while other work will follow earlier work. Again, this sequence must be planned and managed if the project is to succeed. |

Think of it like this: nothing happens in a project that isn’t related to one or more of these four constraints, as depicted in Table 1.3. Clearly, there is a direct and immediate dependency between these four project variables. Changes in one will potentially affect one or more of the other variables. And it is this ‘effect’ that has to be analysed, communicated and agreed (in writing would be good) before the project moves forward. In other words, every time one or more of these variables change, the project should have a ‘time-out’ until a detailed assessment can be carried out to discover what has triggered the change, what the impacts will be and what resulting changes are required. These four variables (now you might see why they are sometimes called constraints) are that important.

Table 1.2 Common project variables/constraints

| Variable | Key points |

|---|---|

| Time |

■ Each project will probably have a prescribed (fixed) window from the initial idea stage through to the completion stage during which all stages and project work must be completed successfully. ■ If there is no latitude or freedom in this time window, the project is said to be over-determined (in this constraint). ■ The amount of time available will determine the schedule of work for the project. ■ Projects can be completed ahead of time/schedule, on time/schedule or behind time/schedule. ■ The amount of time available for the project can have a direct and often immediate effect on the project’s other constraints. |

| Cost |

■ Each project should have a budgeted and approved cost to fund the required work to the required standard during the required time allowed. ■ Some projects are under-funded, some excessively funded, while others are adequately financed. ■ Remember too that the finance available will impact on the other three project constraints. |

| Scope |

■ Each project should specify exactly what work is, and is not, required. ■ There should be no vague terms, ambiguity or missing requirements. ■ The scope should state the standard of the end products whenever possible in quantitative terms, including tolerances, performance finish, reliability and maintainability. ■ As with the two earlier constraints, the scope can also impact on time, cost and resource constraints. ■ The scope will sometimes change once the project is underway, causing delays and increases in costs, or acceleration and/or decreases in cost. |

| Resources |

■ Finally, each project requires that an appropriate range of resources be assigned to complete the scheduled work. ■ Some human resources might require additional training. ■ Resources are often over-allocated, causing scheduling conflicts, delays and cost overruns. |

Table 1.3 Contrasting variable interdependencies

| Variable | If increased… | If decreased… |

|---|---|---|

| Time |

■ Resources could be reassigned to other projects. ■ Scheduled tasks could be delayed. ■ Costs could increase due to prolonged work activities. ■ More time could prove the catalyst in fine-tuning the specification. |

■ Increased resources will be required to compress the work timeline. ■ More costs will be incurred to fund the compressed schedule. ■ The specification may come under review as the project team looks for ways to save time. |

| Cost |

■ Higher skilled resources could be deployed. ■ More resources could be assigned, which could shorten completion times. ■ Additional funding could allow for the upgrading of the original specification. |

■ One immediate way to save money is to shed resources. ■ Another way is to downgrade the specification. ■ With less money, the timeline might shorten if less work is now required, or it may lengthen if the resources now require additional time to complete all the work. |

| Scope |

■ Additional finance could be required to fund the new features and/or the resources required. ■ Better skilled resources may be required. ■ More time may be needed to complete the project. |

■ Money could be saved through the downgraded specification. ■ Resource assignments could be changed to allow less skilled resources to complete the tasks. ■ Time may be saved by taking less functionality from the project, although in some cases the less skilled resources might add time to the project. |

| Resources |

■ With more resources, more money might be required. ■ Completion times could be shortened. ■ With the greater number (and diversity) of resources, opportunities might exist to upgrade the specification. |

■ If resources are removed, the time required to complete the project will probably increase. ■ Money might appear to be saved, although the additional completion time may well erode any savings. ■ The agreed specification may not be completed to the same high level with fewer resources available. |

Worse still, many projects begin their lives with one or more of these constraints already set (that is, not discussed and agreed with everyone involved) independently of the other constaints, and not amended following any changes in the other constraints. The following are typical examples that should strike fear and trepidation into the hearts of many project managers (be aware—they are all real examples):

■ A financial year budget surplus (which must be spent or it will be lost) is suddenly allocated to a project.

■ Finish dates are locked in, due to operational, regulatory and/or other calendar constraints.

■ Contractual arrangements are concluded before the project is fully understood.

■ Assumptions are made about existing resource availability and capability.

■ Reliance is placed on historical data that have not been properly assessed.

■ Inaccurate provisional estimates are made that are not reassessed and revised.

■ The scope of the project is poorly understood (e.g. we require the following [but not limited to] services…).

Critical reflection 1.1

I continue to be astounded at the number of (alleged) projects that organisations are creating, one on top of the other, with mixed results regarding how they are planned and managed adequately over time.

■ What is driving the increase in the number of projects your organisation creates?

■ Are all these ‘projects’ genuine projects?

■ How well are project terms like ‘scope’, ‘time’, ‘cost’ and ‘resources’ understood by your organisation?

■ How would you seek to engage with and persuade your superiors that not all their nominated projects are in fact projects (if this were the case)?

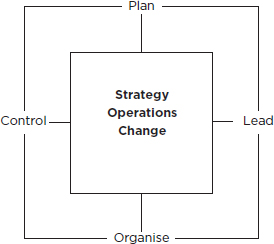

Having distinguished a project from other work activities that are commonly ‘recycled’ (remember that a project is done once), let’s now explore management. Much has been written about the need to manage the project. That responsibility falls to the project manager: the person appointed to bring the project in ‘as scheduled’, as ‘specified’ and/or ‘on budget’ or better. In achieving this goal, the project manager performs a variety of functions, roles and/or tasks, some of which might be far removed from direct management of the project (Wysocki, Beck and Crane, 1995). Traditionally, these planning, leading, organising and controlling functions—as depicted in Figure 1.2—help the (project) manager to achieve the organisation’s goals by working with and through other people. That is, managers get things done with and through other people.

Figure 1.2 Traditional functions of management

Planning

By necessity, project managers must spend a considerable amount of time planning related activities. These could include (but are not limited to) meeting with stakeholders, outlining and defining goals, designing plans and developing management strategies to achieve the project goals. During this ‘functional’ responsibility, the project manager needs to work closely with all stakeholders to correctly identify the business problem or opportunity facing the client. Alternatives should be canvassed comprehensively, with careful evaluation of each one. Delivery milestones and other key outputs, and their specific acceptance criteria, should be discussed, clarified, agreed and documented. Time could also be spent on developing a tentative ‘big picture’ project plan to capture all the macro detail of the project. During this planning phase, it is critical to involve as many of the project stakeholders as possible, thus preventing the exclusion of any key information and the decision-makers. Only with their initial help can the project manager hope to present indicative deliverables, timelines, budgets and resource requirements.

Leading

Every project manager must be able to demonstrate leadership to all project stakeholders. To do this, they will need to be able to inspire and motivate, issue instructions and directions, resolve conflicts and disputes, delegate effectively, communicate openly and honestly, recognise achievement, share the workload (if required) and manage performance. When working with the project team, they will need to influence (where they can) the selection of the team members, take steps to involve the team in planning and decision-making processes (where possible) to a level deemed acceptable, clearly define and communicate the individual roles, functions and skills required, establish agreed performance standards, liaise between the team and all other stakeholders, acknowledge and reward individual and/or team performance and manage performance issues between team members.

Organising

Plans are in place and leadership competencies are present. Now the project manager must identify and schedule both the work to be completed and the resources required. They will need to ensure that all reporting and communication channels are (and remain) open, that decision-making is timely and that the project and its requirements align with the project organisation’s corporate and business priorities, direction and strategies. Clear lines of authority, responsibility and accountability will also need to be established, acknowledged and maintained.

Controlling

This function can only be performed if the other three are in place. To control the project, the project manager will need to closely monitor all aspects of the project to ensure (and reinforce) completion to plan while also acknowledging significant deviations that might dictate a specific response. The project manager can demonstrate their controlling function by ‘walking through’ the project, conducting performance reviews against the agreed key result criteria, managing scope changes, regularly meeting with the team and ‘feeding’ information to all the stakeholders.

What exactly is project management?

Bringing the two words ‘project’ and ‘management’ back together, what progress have we made? Project management refers to the management of project activities that lead to the successful completion and output of a project. The project requires the application of underpinning management principles in planning, organising, controlling and leading the resources of the organisation to realise a one-off specific goal. The management process brings together and optimises the necessary resources to successfully complete the project as agreed, scheduled and reviewed.

Managing projects differs somewhat from conventional and general management assignments, with the key difference being that a project is a limited concept that is usually more narrowly focused than traditional management goals. Other ways to define project management could include any of the following ‘constructed’ definitions:

■ identifying, planning, scheduling and controlling the project requirements

■ negotiating the agreed tradeoff between time, budget, resources and scope

■ managing change initiatives over time

■ managing changing stakeholder expectations

■ scheduling an agreed solution to a specific need, problem or opportunity

■ balancing task and resource decisions (Microsoft Project)

■ creating a unique product or service through a temporary endeavour (PMBOK).

Let’s not get bogged down with definitions, though. Instead, understand what triggers the project, why it needs managing and what it delivers. Remember the four prime constraints that drive the project: time, cost, scope and resources.

So we have reached the point where you (hopefully) understand projects, project life-cycles and project management. The question now is: What do you do with it all? How can the information covered be transferred, applied and developed in the workplace to make any credible inroads into how you plan and execute your projects? Perhaps the answer lies in finally distilling for you what could be called the key principles of project management excellence. Consider the following suggestions:

■ identifying, analysing and communicating the real business need

■ direct involvement and input from all key stakeholders

■ commitment to planning the project in iterative and revised detail

■ defining, agreeing and measuring the targeted benefits

■ evidence of applied governance measures

■ developing explicit, iterative and version-controlled project documentation

■ allowing regular reviews, audits, adjustments and revisions (where appropriate and justified)

■ agreeing on specified and measured outputs

■ proactive decision-making involving all stakeholders (as required)

■ direction, guidance and mentoring from a senior management project group/committee

■ single point accountability with matching (and communicated) authority, along with visibility

■ open, honest, complete and timely communication

■ transparent processes, including roles, responsibilities and standard documentation

■ compliance with an auditable change-control process

■ cohesive and committed teamwork drawn from across the organisation’s expertise

■ balanced and demonstrable leadership from both the ‘dance floor’ and the ‘balcony’.

Wanted: The ideal project manager

Managing projects differs somewhat from conventional and general management assignments, with the key difference being that a project is a limited concept that is usually more narrowly focused than traditional management goals. Through managing, project managers are involved in the process of identifying, planning, scheduling and controlling the true requirements of the project. They ensure that agreed tradeoffs occur to enable project deliverables to be handed over on time, on budget, as specified and with the work being performed using appropriate resources. But over and above the acknowledged traditional functions of management, what other (project) management ‘stuff’ do these people perform? Consider the following suggestions:

■ They are appointed to manage the project throughout the life-cycle.

■ They develop and monitor the iterative project plan and associated documents.

■ They oversee the estimating tasks and scheduling activities.

■ They manage, negotiate and communicate the project scope (inclusions and exclusions).

■ They manage project resource assignments, training and reassignment.

■ They manage the project schedule and project budget.

■ They manage stakeholder expectations.

■ They manage procurement and contracts.

■ They manage quality requirements.

■ They direct and motivate project team morale and performance.

■ They manage all change requests and resultant impacts and approvals.

■ They initiate corrective action and/or reinforcement where required.

■ They track, document and communicate project performance, deliverables and outcomes.

■ They identify, assess and manage project risks.

■ They manage and report relevant issues.

■ They facilitate regular performance meetings:

□ kick-off when the project first gets authorised and registered (concept stage)

□ kick-in when the project is underway (execution stage)

□ kick-out when the project is finalised (completion stage).

■ They coach, mentor and support the project team and other stakeholders (as required).

Traditionally, the above functions have tightly prescribed what management should be. Today, while these anchored functions remain prevalent, the modern manager needs so much more: an active and logical understanding of their workplace systems, people and processes; to be technologically savvy with their information and communications platforms; commitment to continuous improvement and innovation; genuine empowerment of their teams; transparent performance management; and a participative leadership style.

Wanted: The ideal project leader

However, managing the project is not exactly the same as leading the project. To expand on this point, let’s start with a definition. Leadership simply means using your innate or learned skills to influence (and modify) the attitudes and behaviour of an individual and to get them to willingly do something they may not want to do. Table 1.4 provides a snapshot (if not an ‘extreme forced choice’) of the prime differences between managers and leaders. Note that these differences in both managers and leaders are required in projects, although to different degrees and at different times with different people and in a variety of situations.

Essentially, leadership is the ability to influence the behaviour of individuals and to ‘move them in a new direction’. While there are numerous theories of leadership, the collective wisdom of these can be summarised as follows:

■ Leaders require a range of personal traits deemed to be worthy of effective leaders, including energy, integrity, empathy, intelligence and honesty.

■ Leaders have two major ways to influence the behaviour of individuals. One is for the leader to focus on the task (getting the job done) while the other is for the leader to focus on the people (performing the tasks).

■ Leaders should respond to situations and/or contingent factors and variables, and adopt an appropriate leadership style. These factors could include the surrounding culture, the urgency, the experience and maturity of the team, and the nature of the task itself.

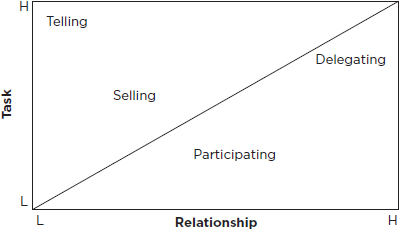

While these theories (and others, such as charismatic leadership, referent leadership, transformational leadership) continue to enjoy popularity, Figure 1.3 compares four different styles that have been identified under the situational leadership theory. The four styles are:

1 telling (autocratic, with no involvement of others)

2 selling (largely directive, with limited attempts to explain actions and/or to convince others that the leader’s actions are right)

3 participating (increasingly supportive, where ideas are called for and openly discussed with others)

4 delegating (highly democratic and supportive, where the direction and decision-making is left to the team).

In the situational approach, a ‘sliding’ leadership continuum ideally exists between the autocratic leader and the democratic leader. While a project manager needs both, the styles displayed are very different. Consider the comparison shown in Table 1.5.

Table 1.4 Separating managers and leaders

| Manager | Leader |

|---|---|

| Administrates, regulates | Innovates and creates ideas |

| Maintains, reinforces | Develops, encourages |

| Controls, contains | Trusts, experimental |

| Systems, process | People, capability |

| Bottom line, figures | Horizon, results |

| Status quo, procedure | Challenges, improvements |

| Hierarchy structure | Synergy structure |

| Short term, immediate | Long term, future |

| Task focus | Solution focus |

| Formal authority, ‘I’ | Interpersonal skills, ‘we’ |

| Does things right every time | The right thing, learning |

| Solves problems, takes charge | Involves, autonomy |

| Adheres to direction | Supports and guides |

| Us and them mentality | Us together |

| Blaming | Actively listens |

| Coercive power | Cooperation |

| Rewards work | Rewards creativity |

| Seeks compliance | Values performance |

| Superior, legitimate status | Mentor, coach |

| Directive, forcing | Lead, sharing |

Clearly, both management and leadership are required to plan and manage the project. Traditional functions of management should not be discarded too quickly as irrelevant in modern project management, nor should notions of leadership dominate the project landscape. The effective project manager needs to know when to manage and when to lead, as well as what management looks like in an operational context and what leadership looks like in a strategic context.

Figure 1.3 The continuum of situational leadership

Table 1.5 The leadership continuum

| Telling (task focus) | Delegating (relationship) |

|---|---|

| Dictatorial (autocratic) | Democratic (laissez-faire) |

| Highly directive | Highly supportive |

| Task takes priority | Relationship takes priority |

| One-way communication | Two-way communication |

| Achieves results through directives | Achieves results through consensus |

| Limited need for rewards | Opportunity for rewards |

Welcome to the dark side of leadership. While much of the positively biased literature supports developing effective leaders with an assortment of leadership theories, models and principles, there is another side of leadership prevalent within organisations of all shapes and sizes, including both project management and client organisations. With research suggesting that half of those in leadership positions fall short in leading others (not to mention the tenure of leaders is steadily dropping), the shortage of effective leaders in your projects should be a genuine concern for everyone involved. There is good news, though: the cause is not that hard to find, as it is a simple question of character. There is bad news too: character is one of the hardest things to accurately, precisely and individually define.

Recall that management and leadership are not synonyms for each other: they are different sets of knowledge and skills, making up the practices, behaviours and attitudes required when working with and through other people. So, as we focus on leadership, your understanding of leadership development (estimated to be worth well over $50 billion a year) and effectiveness will actually benefit from exploring the dark side of leadership failure, or the prevalence of bad leadership.

With Burke’s (2006) help, let’s jump straight in and reveal some of the common notions underpinning leadership failure, and see whether you are familiar with any of the ‘failed leaders’ described below. The leader:

■ is stupid with little talent, intelligence or industry-specific knowledge

■ has an inability (or lack of confidence) to execute direct and/or support plans

■ displays incompatible ethics, beliefs, moral compass and/or values

■ is resistant to working towards hard-to-achieve outcomes

■ is insular, as they ignore the needs and welfare of their followers

■ reveals that self-interest is the sole focus of everything they do

■ lacks self-control, and is self-indulgent and unreasonable

■ is unable or unwilling to adapt to new ideas and practices

■ engages in psychological or physical harm to others.

That was a little scary to say the least, as it wasn’t a great list of positive behaviours. But these descriptions are often accurate for leaders who simply do not, or cannot, actually do what their leadership role requires. Collectively, the above list simply categorises leaders as either unethical (failing to distinguish between right and wrong) or incompetent (failing to achieve the desired results), but you can work out which description belongs where.

Recall that leadership is very much about ‘owned’ behaviour: who people are, how they act and what they say; it isn’t about what they know or how bright they are. It shouldn’t be about intelligence tests, talented and gifted people and winning popularity contests. Below are some additional behaviours that historically have resulted in leadership derailment—or, to put it another way, seven habits of spectacularly unsuccessful people (Finkelstein, 2003). These leaders have:

1 an over-optimistic and over-estimated view of how much control they had over the organisation and believe the organisational success was due entirely to their efforts

2 a lack of any clear and transparent boundaries between their personal interests and their organisational interests, believing the organisation is a natural extension of themselves in all respects

3 a fixated belief that they have all the answers—much like a control freak who listens badly, ignores advice and pushes dissent underground

4 an intense dislike of criticism, seeking to eliminate anyone not 100 per cent behind them

5 an innate belief that they are always right

6 stubbornness in doing what they have always done in the past

7 they tend to be consummate organisation spokespeople, as they obsess over the organisation’s image in the public eye. They also under-estimate obstacles.

Clearly, dysfunctional leadership is prevalent in project management. And for some, the command and control mentality of some practitioners, along with overt pressure to adhere to the plan because the ‘plan is everything in project management’, may well contribute to leadership failure, among other contributing factors. Lombardo, Ruderman and McCauley (1988) believe that leadership should be more about exercising discretion, being organisationally savvy, dealing with organisational complexity, directing, motivating and developing subordinates, pursuing excellence, being self-confident, honourable and composed, and even being sensitive.

Just as when you identified the leaders who you knew had failed, go on to identify the successful ones, the effective ones, the leaders who combine business knowledge with personal awareness, who are open to feedback, take risks, build genuine interpersonal relationships and model leadership that supports both innovation and creativity.

Critical reflection 1.2

Think about what leadership (effective or otherwise) actually delivers to your projects.

■ What type of leader do you prefer to work with, and why?

■ How did you react as you read through the section on the dark side of leadership?

■ Were you mentally identifying different people in your project organisation?

■ Why are both management and leadership important to your successful project outcomes?

Developing management and leadership attributes

In more specific terms, what types of skills, knowledge and abilities (attributes) are required by a project manager/leader? Are they generic or particular to project management? Can they be acquired or does a person need to be born with them? Are they possessed by everyone?

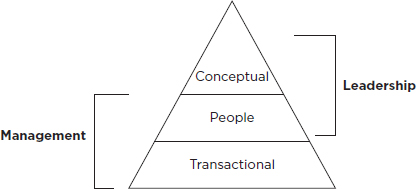

In many respects, the project manager does not have the time to become fully acclimatised to the job. In fact, they usually hit the ground running, with very little time—if any—to climb the ‘learning curve’. Remember, projects have a sense of urgency, are time limited, and have precise objectives and influential stakeholders all riding on the project ‘wave’. As depicted in Figure 1.4, the manager clearly needs to perform on a number of fronts. To do that, the following are of increasing and paramount importance:

■ conceptual or transformational attributes to allow them to see the big picture and avoid getting bogged down in the finer detail:

□ thinking strategically to drive organisational renewal

□ arousing a sense of excitement, purpose and adventure

□ creating and embracing change

□ building intelligent, learning and adaptable organisations

□ transforming ideas and visions into reality through words, behaviour or symbolism

□ investigating issues and problems, and initiating appropriate action

□ building and inspiring trust by being consistent, dependable and persistent

□ creating creative environments

□ encouraging an entrepreneurial spirit

□ managing the political agenda

□ instilling a passion and drive for excellence

□ understanding the operational systems and procedures within the organisation

□ collaborating with diverse stakeholders

■ interpersonal or people attributes to allow them to work with and through other people to get the job done (remember our earlier definition of management). These skills will allow the project manager to deal positively and effectively with project stakeholders:

□ using written and verbal communication

□ negotiating agreements

□ resolving conflict and disputes

□ seeking solutions through diplomacy and mediation

□ offering coaching and mentoring

□ giving individual attention

□ practising active listening

□ building trust

□ influencing others

□ facilitating consensus

□ overcoming resistance to change

□ being authentic, ethical and (intellectually) stimulating

□ demonstrating humility, honesty, integrity and respect

□ practising assertiveness and empathy

■ technical or transactional attributes to allow them some intimate knowledge or understanding of the project processes and their actual work. Remember, though, that the project manager is not there to ‘do the work’; they are there to ‘manage the doing of the work’. These skills will allow the project manager to work closely with the product, service and/or processes involved in the project:

□ knowing the standard operating system protocols

□ tracking, reviewing, reporting on and controlling performance (scope, time and cost)

□ proactively monitoring risk and treatment

□ communicating with stakeholders

□ promoting the project internally

□ ensuring all work, health and safety requirements are complied with

□ adhering to the required statutory and regulatory conditions

■ a demonstrated managerial ability to perform the traditional functions of management—planning, leading, organising and controlling

■ leadership to build and sustain a project vision for the team over time

■ an ability to see the future while working in the present and learning from past mistakes. Strategic expertise is not the same as operational expertise.

■ a background aligned with the desired project outputs

■ a high degree of business acumen, covering areas of finance, marketing, HRM, contracts, procurement, logistics or other relevant disciplines

■ a sense of entrepreneurial energy to drive and sustain the project through the change process

■ project management knowledge (PMBOK or similar) and application expertise (real-world experience and skills)

■ technological fluency with emerging technologies and platforms

■ a commitment to coaching and mentoring.

Collectively, these attributes have one thing in common: they identify a project manager who possesses a range of skills, knowledge and abilities to deliver the project on time, on budget, as specified and using the prescribed resources. They also do one more important thing: they confirm the status of the project manager—status from an authority context, not from celebrity. In my experience, far too many project managers get suddenly promoted (sometimes from obscurity, sometimes from the position of business analyst or a functional manager) and are made accountable for the project without also acquiring the mandatory, documented and disseminated authority to actually ‘manage’ the project. Without authority, there is no visibility or accountability.

And let’s be honest: a great many project organisations are yet to adopt detailed project management position descriptions that would help project managers achieve this status. The truth is that too many organisations still pretend that their projects are managed.

Figure 1.4 Management and leadership

The art of delegation

So managing and leading are both critical attributes required by the project manager (and associated roles). But what about the process of delegation? Delegation and dumping both start with the letter ‘d’, but are worlds apart in meaning and application from a managerial perspective, and should not be used as synonyms for each other.

Critical reflection 1.3

Traditional (linear or waterfall) project management is often criticised as involving too much command and control from those who manage the projects.

■ Having read about managers and leaders, think about your managers and whether they are guilty of this mindset. Is there a balanced approach to how they manage through their formal authority and how they demonstrate leadership through valuing capability, autonomy and performance, or do they favour one over the other?

■ How do their management and leadership practise impact your contribution on the project?

Clearly, project management is crying out for competent managers and leaders—ideally rolled into the one project manager.

Delegation is about empowering subordinates to carry out their assigned tasks to achieve the required results within their area of responsibility. It involves giving subordinates the (visible) authority they need to complete the tasks. And while some might disagree, the subordinate is responsible while the project manager remains accountable for the completed task.

But is delegation simply handing over everything that needs to be done in one massive task bundle, or is it more of a staged delegation process—or what is commonly referred to as degrees of delegation? Consider the following example adapted from Gido and Clements (2015), in which delegation expands over six different stages (and time periods) from the lowest degree of delegation (Level 1) through to the highest degree of delegation (Level 6). In this example, the task is to ‘investigate a problem’, although you will notice that the degree of delegated authority increases significantly with each level.

■ Level 1: ‘Report back all the information you collect and I will decide on the next step.’

■ Level 2: ‘Report back all the information you collect, let me know what the options are and recommend one for me to decide.’

■ Level 3: ‘Let me know what action you want to take and wait for my approval.’

■ Level 4: ‘Let me know what action you want to take and do it unless I say otherwise.’

■ Level 5: ‘Take action and let me know what you did.’

■ Level 6: ‘Take action and decide whether you need to tell me.’

See how the authority and responsibility increase from Level 1 through to Level 6. Imagine the empowerment, the trust and respect each party has for the other between Levels 1 and 6. Clearly, different degrees of delegation are appropriate for different people and in different (project-specific) situations. Never rush delegation or assume that everyone is ready for Level 6, as the reality will quickly show you otherwise.

In making these delegation decisions, you might also like to factor in someone’s motivation, confidence, availability and willingness to accept the delegated role, as their technical competence (knowledge and skill) to perform the allocated task should never be the sole determinant in the decision. Your project may well be full of competent people; sadly, this doesn’t mean everyone will step up when authority is delegated to them.

Competing project management methodologies

It is becoming increasingly difficult these days to work on any project, to read any project manager’s job advertisement (or position description for that matter) or to provide any project management consulting services without coming across some reference or requirement pertaining to ‘things’ called PMBOK, PRINCE2, Agile, Lean, Project PRACTITIONER or some other suite of institutionally endorsed, commercially marketed, proprietary IP or perhaps, in some cases, just generally (or loosely) accepted project management methods. While often project, industry or government specific, a methodology is a prescriptive way of conceiving, planning, executing, finalising and evaluating projects.

With new methodologies constantly being promoted, the choices are not only expanding but also possibly diluting the ‘sausage behind the sizzle’. And while it is true that some project management methodologies present as metaphors for on-time, on-budget and in-scope delivery, it is important to remember that they must offer more than merely an illusory fabric of control. If—and it is a big if—the methodology aligns with both strategic initiatives and operational realities (if required), adds value to the project and is underpinned by targeted professional development initiatives that address technical, social and strategic knowledge and skills, and it is also constantly reviewed and adapted to reflect the (changing) strategic direction of the organisation, then the methodology will serve the organisation and the project well.

The ‘right’ project methodology plays a crucial part in guiding the project’s success. Projects can’t be allowed to merely meander from start to finish: they need to be planned, directed, executed and managed in line with a workable, agreed and communicated approach. So, if the methodology itself is wrong, missing in action, copied from someone else’s website or an exact, unedited copy of PMBOK, PRINCE2 or another framework, then intuitive, siloed, fractional and disputed project management may well take over (sometimes, I should note, with incredible success!). Don’t get me wrong though: simply imposing the PMBOK predictive or plan-driven approach, PRINCE2, the adaptive Agile model, Project PRACTITIONER or another methodology will not, by itself, ensure project success either. Clearly there needs to be some alignment between what is being delivered, how that will be delivered and who will be doing the delivery.

The Project Management Body of Knowledge (PMBOK)

PMBOK (try to get the pronunciation right—‘pim-bock’) stands for the Project Management Body of Knowledge and is the de facto global standard for project management. Revised every four years by the Project Management Institute (PMI, 2013) of America Standards Committee, PMBOK ‘is an inclusive word that describes the sum of knowledge within the profession of project management and includes knowledge of proven, traditional practices that are widely applied, as well as knowledge of innovative and advanced practices’. So what effectively started out as a basic reference (acknowledged in the first 1996 edition as being neither comprehensive nor all-inclusive), a body of knowledge or applicable practices has grown to become (for some) an international mark of project management best practice and, ultimately, excellence.

While the ten processes in PMBOK are presented as separate concepts and chapters, they interact with each other continually throughout the project life-cycle from start to finish, and cannot be studied and applied in isolation. Within each project in which you are involved, all ten will require initial and ongoing investigation, discussion, agreement, documentation, dissemination, review and updating.

Further, as the project evolves throughout the project life-cycle, the amount of information required by each will vary in both quantity and impact as different decisions are made by the project stakeholders. And while some practitioners find this interdependent relationship between all ten domains difficult to manage, your project management success is predicated on integrating all ten repetitiously throughout your project as decisions in any one may cause immediate ripple effects in the remaining ones (without your consent, let alone without your awareness that changes have in fact occurred). Table 1.6 fleshes out what the ten processes involve and, more importantly, what some of the critical success factors are for each one.

To make sure your projects don’t get away from you (and regardless of your role on the project), remember that these are the ten ‘things’ that will either help or hinder your project management planning and delivery activities. While you don’t need to be the qualified or incumbent procurement manager, or the quality manager, finance manager, communications manager or risk manager for the project, you do need to understand how each of these knowledge areas impacts in your project.

PRINCE2

While PMBOK appears to dominate the project landscape, another contender is also well known and used. Known as PRINCE (PRojects IN Controlled Environments), it is a structured method dating back to its origins in 1996 for effective project management with information and communication technology projects, among others (Office of Government Commerce, 2005). Today, PRINCE2 is a de facto standard used extensively in the United Kingdom by both government and the private sector, and is also gaining recognition internationally.

As a methodology, PRINCE2 adopts a process-based approach to project management, with each process defining the minimum requirements for appropriate management activities and base components that must be carried out during the project. With its focus on aligning both projects and business, PRINCE2-style projects are always focused on delivering specific products to meet a specific business case. In this way, the definition and realisation of the business benefits continue to be the driving force behind the project.

PRINCE2 has eight distinctive management processes that cover all the project activities from beginning through to completion. They are:

1 directing a project

2 planning

3 starting up a project

4 initiating a project

5 controlling a stage

6 managing product delivery

7 managing stage boundaries, and

8 closing a project.

Table 1.6 PMBOK knowledge areas

| Knowledge area | Interdependent processes | Critical success factors |

|---|---|---|

| Scope management (requirements) | Scope management includes the processes required to determine and manage project expectations and deliverables, including planning, authorisation and controls throughout the project. |

■ Client engagement ■ Be realistic about your capability ■ Create a common understanding ■ Complete, unambiguous requirements ■ Formal change controls |

| Time-management (schedule) | Time management includes the processes required to determine and implement the project schedule and to manage the agreed timelines with appropriate intervention strategies throughout the project. |

■ Plan the work and work the plan ■ Activity is not the same as accomplishment ■ Measuring actual performance against planned performance ■ Report performance regularly ■ Authorising corrective action immediately |

| Cost management (budget) | Cost management includes the processes required to identify, analyse and refine project costs and to ensure project costs are managed, reported and controlled throughout the project. |

■ Realistic and reasonable estimates ■ Time-phased cumulative budget forecast (cash flows) ■ Earned value reporting ■ Contingency reserves |

| Quality management (technical excellence) | Quality management includes the processes required to manage the quality planning, assurance, control and improvement processes and policies throughout the project. |

■ Commitment to quality improvement ■ Regular monitoring, inspection and testing |

| Human resource management (performance) | Human management includes the processes required to determine the resource needs, assignment priorities, development needs, performance issues and evaluation throughout the project. |

■ Establish trust, allow participation and build commitment ■ Encourage diversity, respect and ethical behaviour ■ Clarify roles and expectations ■ Value team member contributions ■ Performance manage and celebrate success ■ Provide opportunities for professional development |

| Communications management (information) | Communications management includes the processes required to ensure that timely and appropriate information is collected, disseminated and evaluated through managing formal and/or semi-formal structures throughout the project. |

■ Established protocols for regular and open communication ■ Timely, concise, accurate, complete, free of jargon and not offensive ■ Establish a document control system (or communications register) |

| Risk management (probability and impact) | Risk management includes the processes required to manage the identification, assessment, treatment, monitoring, controlling and evaluation of positive and/or negative project risks throughout the project. |

■ Have a step-by-step way of dealing with risk ■ Be proactive in identifying risks ■ Address high-priority risks ■ Assign treatment strategies to people with the appropriate capability and delegated authority ■ Watch out |

| Procurement management (agreements and contracts) | Procurement management includes the processes required to manage procurement activities throughout the project. |

■ Realistic ■ Contract management |

| Stakeholder management (vested interests) | Stakeholder management includes the processes required to identify, plan, manage and control stakeholder engagement throughout the project. |

■ Identification, profiling and engagement strategies |

| Integration management (unified application) | Integration management includes the processes required to integrate and balance the project management knowledge areas—scope, time, cost, quality, communications, human resources, risk, procurement and stakeholders—throughout the project. |

■ Creating the project proposal ■ Developing the project plan ■ Directing and managing the work ■ Monitoring and controlling performance ■ Performing integrated change control ■ Closing down the project |

Impacting throughout each of these eight processes are a further eight components: the business case, organisation, plans, controls, management of risk, quality in a project environment, configuration management and change control. It is important to remember that neither methodology (nor other commercial offerings not cited here) will arrive in your project management office (PMO), meeting room, intranet, document management system or Gantt chart ready for immediate and exhaustive application.

The many proponents of PRINCE2 are quick to cite the many benefits the methodology provides as a comprehensive, consistent and repeatable set of best-practice protocols and practices that deliver project and business effectiveness and efficiency through:

■ best-practice guidance

■ a focus on business justification

■ a well-defined project support structure

■ manageable project stages

■ regular progress reviews

■ controlled decision gates

■ explicit stakeholder involvement

■ open communication channels.

Agile

As a popular methodology, Agile comes in different shapes and sizes, including:

■ Scrum (a term derived from the game of Rugby)

■ Dynamic Systems Development Method (DSDM)

■ Extreme Programming

■ Lean Development, and

■ Feature-Driven Development.

Agile differs from what could be termed ‘traditional’ project management, where the requirement or specification is a well-defined, mandated (technical) solution that is agreed and recorded as the scope baseline when the project starts. While there will often be some movement in the client’s expectations over time, the nominated deliverables remain (relatively) rigid in this traditional, plan-driven and sequential approach (also known as the Waterfall Model).

Popular with software developers, Agile supports the evolution of the client’s prioritised requirements (or features and scope) as the project unfolds over time, while the resources and time allowed remain fixed in this value-driven approach. Advocates would argue that the approach enables a closer relationship between the client and the developers, and fosters ongoing collaboration, creative input and less of the document-dependent and the command and control management style evident when the project is all about the plan, rather than the client’s evolving requirements and solution.

Given the iterative nature of Agile projects, planning is delayed as late as possible within each of the multiple phases (or releases), as there is an acceptance that the client’s requirements will change throughout the project and that these changes should be welcomed. To support these changes, client involvement in giving prompt feedback, making decisions, setting priorities and resolving problems is paramount. While some project practitioners may shy away from change, Agile projects focus on technical excellence, good design, continuous testing and quick results, with the client driving whether they have received enough functionality or benefit from the work completed to date.

Clearly Agile isn’t going to suit every project—be that software development or something else. It certainly works with small software development projects, multiple-phased delivery with a short timeframe, projects with small and dedicated teams, and projects requiring the full involvement of the client.

Finally, while Carroll and Morris (2015) highlight some of the alleged differences between both traditional and Agile projects in Table 1.7 (along with my contributions), they are not exhaustive and have been written from an Agile perspective. That said, it should help you analyse how effective your own methodology might be when referenced against these same criteria.

Lean

Lean can best be described as a revolutionary way of doing business—whether making decisions about operational priorities or strategic initiatives.

With a legacy dating back to the quality movements in post-World War II Japan, the 1980s and 1990s, and other continuous improvement efforts, Lean focuses on satisfying the client’s requirements through quality management measures that collectively reduce waste in the value stream (Kliem, 2016). By placing the client in the foreground, Lean changes how stakeholders interact and how materials are acquired, processed and delivered.

Table 1.7 Comparing traditional and Agile projects

| Traditional project | Agile project |

|---|---|

| Directed team | Self-organising team |

| Take directions | Takes initiative |

| Rewards the individual | Rewards the team contribution |

| Competitive environment | Cooperative environment |

| Adheres to process | Seeks continuous improvement |

| Reactive | Proactive |

| Plan driven | Value driven |

| Sequential delivery | Frequent delivery |

| Fixed requirements | Evolving solutions |

| Change averse | Change responsive |

| Gantt charts | Burn-down charts |

| Scope, time and cost progress measurement | Working products as progress measurement |

With globalisation one of the biggest drivers behind Lean (others include cost reduction, limited resources and information technology), clients want their expectations and requirements converted into competitive price and quality outcomes. As a customer-focused approach, Lean places the client in the centre of the project as it seeks to remove processes and operations that add little or no value.

So what does it take to manage and lead a Lean project? While the project manager doesn’t need to be a Lean expert, the following concepts, techniques and tools will serve as an introduction to where their focus should be.

■ Investigate the context (and the status quo) across both brownfield (existing) and greenfield (new) project environments.

■ Map both the current value stream process in delivering a product or service to a client and the future value stream process to gain valuable insights into continuous improvement opportunities, potential waste removal and increased quality.

■ Understand and define the client’s requirements with specifications or even a model to try to avoid scope creep, cost overruns, schedule delays and constant rework (among other factors).

■ Collect relevant and timely data in support of recommendations regarding future value streams.

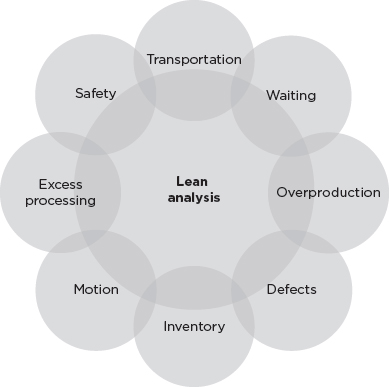

■ Perform detailed analysis to locate the interrelated sources of problems, non-value-added waste or muda (the Japanese word for waste) as shown in Figure 1.5.

■ Apply a variety of Lean techniques and tools to address one or more of the identified forms of waste. These could include increasing stakeholder motivation, defect prevention, safety enhancements and improved maintenance.

■ Formulate and present appropriate recommendations that are ‘mentally digestible’ to different levels of management to gain their explicit approval.

■ Develop and action the project management plan in which the client’s requirements, waste removal and quality improvement are the centrepiece.

Figure 1.5 Performing Lean analysis

Advocates of Lean, including Kliem (2016), are not shy about promoting the promised benefits, including:

■ understanding client values

■ improving cycle time

■ greater flexibility

■ reduced capital expenditure

■ leveraging technology

■ lessening fear

■ overcoming siloed mentality

■ reducing overhead costs, and

■ engendering creativity.

That said, Lean faces challenges (as with other methodologies) in creating and sustaining the value stream. These include:

■ dealing with entrenched bureaucracy

■ a lack of demonstrated management support

■ a history of past failures

■ legacy technology

■ standard operating procedures with traditional accounting practices

■ different management styles

■ protected operational processes.

Clearly, Lean is capable of delivering many benefits to any project, although it does not present a default position. Like any other methodology, Lean on its own will not guarantee project success. For some, it will present another layer of documentation, process and approvals which will only serve to overlay the project with added steps and responsibilities. For others, Lean will bring a clarity to their projects in delivering on client expectations by fully understanding the environment, the processes and the outcomes the client is wanting for the project to be successful.

Project PRACTITIONER

By now you should be becoming more familiar with a number of different internationally recognised and/or proprietary project management methodologies, frameworks, processes and procedures, not to mention the progress you have made in developing your own tailored approach to planning and managing your projects. While operational activities—known as business as usual (BAU)—will continue to drive and sustain routine, everyday work for many organisations, there is growing pressure to create and facilitate medium- to long-term change in order to remain not only viable, but commercially competitive.

This change process is now known as project management: an approach to planning, managing and delivering projects. Projects are a unique set of activities that sit outside of everyday operational activities, which need to be completed to achieve a certain objective and/or benefit within an agreed scope, timeframe, budget and resource allocation. The discipline and practice of project management provide an over-arching framework (methodology or process) that facilitates the logical progression of an idea (change) into a project and thus into a deliverable (final product or service) that someone wants and will accept. Part theory, part intuition, part process and part ‘what worked last time’, project management must be supported by scalable, simple and easy to follow documentation (no two projects are identical in their uncertainty and complexity), if consistency, transparency, accountability, professionalism and visibility are to be demonstrated across each project and everyone involved in it.

My proprietary methodology, Project PRACTITIONER, is founded on a simple and centralised electronic platform with supporting documentation and procedures. All project information can be captured, displayed, refined, filtered, reported, updated and communicated in a step-by-step, secure and scalable format, providing both oversight and insight into all aspects of the project’s performance against the plan. It offers:

■ contemporary industry best practice

■ practical and user-friendly documentation

■ uniform project management language and practice

■ a concise and scalable approach to planning, managing and delivering projects.

A raft of tools, templates, registers, training and support provides the foundation tools and a holistic approach for planning and managing the project from start to finish. Project PRACTITIONER integrates best practice drawn from a number of different competing methodologies, practical functionality and helpful tools to enable accurate and timely project tracking, reporting and controlling of schedule delivery, technical performance, budget allocation and contractual compliance.

Integrating all ten knowledge areas into a single document (which I call the project management plan, although its intent is far broader), Project PRACTITIONER enables the student and practitioner to create the following (with supporting evidence):

■ all ten PMBOK knowledge areas ‘on-a-page’

■ an A3 template for mapping your ‘life-cycle management approach’

■ an ideas register for all organisational-wide suggestions and thought bubbles

■ a business case with a complete assessment, justification and identified benefits, with supporting evidence

■ a project register to communicate the project’s official status

■ a project charter with supporting evidence

■ a work breakdown structure (WBS)

■ a risk register with supporting evidence

■ a project plan with supporting evidence

■ a change request form

■ a variation register

■ a performance report

■ a progress claim/payment form

■ a completion report

■ an evaluation (benefits realised) report

■ a lessons learned register

■ project management competency assessment maps

■ a professional development plan

■ a project management maturity self-assessment report.

These templates are not standalone templates that you complete once and in isolation from the other templates: each has some form of codependency or interdependency that must be maintained throughout the project from start to finish, as a change in one document may well produce a ripple effect (or something more serious) in other documents.

With Project PRACTITIONER, all the required documents live in the one place: the project management plan. Often misunderstood as simply the project schedule, this plan is an all-encompassing document that captures every original piece of information (perhaps known as baselines in some situations), all revisions, all performances and all outcomes. Formatted in conjunction with the life-cycle approach to project management, the Project PRACTITIONER project plan is a living document that will grow in detail exponentially (as it should) over the life of the project.

Choosing a methodology

So there is considerable choice when it comes to choosing one methodology over another. Each methodology clearly has its proponents, advocates, champions and hard-core users, with probably just as many unaware and potential users. Perhaps they all need to be reviewed in terms of what your specific business needs and then scaled (where appropriate) to your projects. However, they all provide a scalable set of tools, techniques, processes and components that you will need to closely and carefully tailor to your particular project needs and perhaps equally, if not more importantly, to the needs of the project organisation itself.

This aligns with the case put forward by Cleland and King (cited in Nicholas and Steyn, 2008) that there are five general criteria to consider when determining whether project management methodologies are in fact required by your project:

■ the degree of unfamiliarity with the project, as distinct from the ordinary and the routine (operational priorities)

■ the magnitude of the effort required to plan and manage the project (resources, capital, equipment, facilities, etc.)

■ the rapidly changing environment, due to client needs, innovation, shifting markets, consumer behaviour and many other factors

■ the level of interrelatedness required by the project to build lateral relationships between functional areas and organisation wide, as distinct from self-serving and independent functional areas

■ the potential loss of organisational reputation resulting from a project failure (financial ruin, loss of market share, damaged reputation, loss of future contracts, etc.).

Critical reflection 1.4

Much has been written about methodologies, what they are and what they offer project planning and management.

■ What is your understanding of the different methodologies and the alleged value they deliver to your projects?

■ Having read (and conducted further research) about linear, incremental or perhaps iterative methodologies for planning and managing your projects, which approach do you favour and why?

■ Rather than using one of these methodologies, are you more inclined to develop your own methodology (and if so, why)?

■ What genuine value will following your project management methodology deliver to your projects, and at what cost?

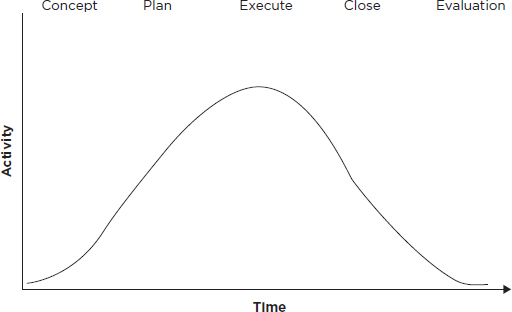

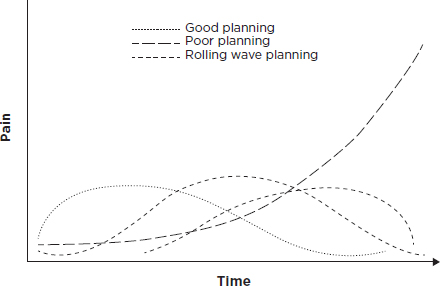

Navigating the project life-cycles