Developing and maintaining individual and team performance

Key points

■ Elements of the HRM plan

■ Working with multi-generational project teams

■ Encouraging team diversity

■ Facilitating team evolution

■ Supporting the team ground rules

■ Appreciating personality differences

■ Professional development opportunities

■ Theories of motivation

■ Measuring, reporting and reinforcing team performance

■ Working with positive and negative conflict

In practice

The only way you will ever convert a project plan into a reality is with and through resources. And those resources are mostly people—the individuals, groups and teams working on the project.

Another reality concerns the (fluctuating) motivation, energy and commitment these assigned resources will display. And as we know from earlier chapters, different stakeholders each have different expectations that change throughout the project—as they should. Given this, and the enormity and potential complexity of other project variables, building and sustaining skills and commitment throughout a project constitute another (often ignored) integral component of project management.

Think about the people with whom you currently work on your projects. Are you simply a bunch of individuals who just happen to work together at times, in the same physical (or virtual) location? Or are you an active team member, part of a loyal and cohesive team working collaboratively together to achieve common goals? Perhaps you might work alone (either by decree or by choice), with little or no interaction with others.

What a dynamic mix each of the above scenarios presents if you have to manage, or even simply interact with, these people. How can we possibly balance the needs of the individual with the needs of the team, let alone with the over-arching needs of the project? How do you manage competing interests, two or more direct reporting relationships, diversity and disputes, not to mention motivation or power? Perhaps the better question to ask is: What could really be achieved if we built and sustained the team?

Chapter overview

Little gets done without people. Regardless of the language used—activity, task, stuff, work, actions, priorities or projects—human resource intervention will be needed on one level or another. And it will need to begin well before task performance is monitored or project results are achieved.

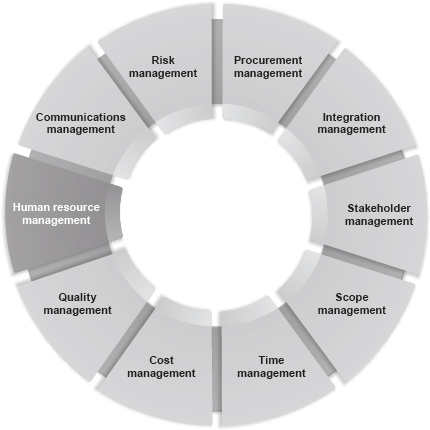

PMBOK (2013) suggests that human resource management (HRM) includes the processes that ‘organise, manage and lead the project team’. So does it pretty much come down to these three simple words, or is there more to it? Such a succinct sentence gives little, if any, clue to the myriad challenges and opportunities the project organisation, stakeholders, project managers and teams will face throughout the life of the project.

As with the other PMBOK processes, the management of human resources doesn’t happen without a plan that captures fundamental information about the people involved in the project, and their roles, responsibilities, skill set, reporting relationships and development needs. Once this information is documented, the project team can be confirmed, along with its members’ location, availability, experience, attitude, knowledge, skills and costs—all factors that drove their acquisition by the project.

So the team has been pulled together. Does it stop here, or will the individual and team (developmental) needs warrant some investigation along the lines of competency levels, interaction and the overall team environment? Remember that teams are often illusory: a bunch of people occupying the same floor space doesn’t make them a team (perhaps just a crowd). As part of this development, ongoing performance management will be crucial for enabling the team to perform at the level required by the project.

Planning for human resource management

Much of the emphasis in this book so far has been on the scope, schedule and cost baselines, and their interaction with other project management processes. While this emphasis is justified, no project can enjoy any measure of success without the application and commitment of the project’s human resources (on either a full-time, part-time or contract basis).

The best-laid project plans will quickly and comprehensively be derailed, if not destroyed, by resources that lack the energy, drive, focus and commitment to achieve the project’s output and outcomes. With the ‘wrong’ resources doing the ‘right’ work, the project will invariably be challenged—or worse, fail. And that failure will not occur overnight: it may be gradual or even invisible. There may be early warning signs (often missed, misread or mismanaged), followed by alarming danger signs, followed not too long afterwards by impending disaster that will seriously challenge even the best project managers.

While theory will suggest that these team members are actively involved in the project’s planning and decision-making activities, a strategy is required to prevent the project becoming ‘damaged’ by the escalation of these resource issues—be they about performance, personality or relationships. To keep the project team on track, the project manager needs to build courage, commitment and performance throughout the project’s life-cycle—from idea to completion.

The HRM plan establishes the baseline for identifying the prerequisite resource needs (and necessary skills) for the project’s success. In an operational climate characterised by different shades of competing priorities, functional manager reporting lines, downsizing, restructuring, job-sharing, outsourcing and contracting, the resource landscape has become increasingly competitive as resources are performing multiple roles in their operational positions (and only getting paid for one), well before they get acquired by the project. A well thought-out resource management plan could contain the following information:

■ internal or external acquisition strategy

■ roles and responsibilities

■ reporting relationships

■ acquisition and release timetables

■ identification of professional development needs

■ team-building strategies

■ plans for recognition and rewards

■ geographical location

■ resource calendars

■ performance management procedures

■ work, health and safety issues

■ dual reporting relationships (project and operations)

■ communication protocols

■ organisational structure and culture

■ standard operating administrative procedures

■ escalation procedures for resolving issues.

There is a wide-ranging array of generic tools and techniques useful for putting together the resource plan (many of which you will already be familiar with, although some perhaps not), including the following examples of text-based information and graphical formats:

■ organisational chart

■ stakeholder responsibility matrix

■ position (role) description

■ responsibility assignment matrix

■ training register

■ personnel files

■ contractor agreement

■ performance reviews

■ application forms

■ social media

■ résumés

■ aptitude tests

■ psychological tests

■ behavioural interviews

■ reference checks

■ employment contracts

■ organisational standard processes

■ lessons learned log.

Resource scarcity is becoming increasingly common as a finite number of resources are tasked to perform multiple, competing priorities—operational and project work. Add to this the increasing expectations that clients have towards the project’s objectives being met—in scope, on schedule and within budget—and it is evident that resource planning can never be an ad hoc activity. It remains fundamental to the project’s planning, implementation and finalisation stages as it endeavours to constantly match the right skill set with the right activity in the changing landscape of the project life-cycle.

Critical reflection 8.1

Getting resources on board your project involves much more than finding out who has what skill, who is available and what it will cost.

■ Review what process your project has used to resource the project: direct appointment or some merit-based system.

■ Does this always result in getting the best people for the required work?

■ Do you think the PMBOK resource management planning process is something you could create and implement in your projects for baselining their prerequisite resource needs?

Acquiring the multi-generational project team

In acquiring the right resources at the right time to be a successful team in delivering the project’s objectives, the project organisation and management need to assess their level of control and influence over the resources they require in the team. With operational priorities and reporting relationships driving the daily availability of nominated resources, collective bargaining agreements, subcontractor arrangements and other nuances of the modern workplace, a number of factors will need to be considered and planned for in the early stages of the project (and controlled in the later stages). These could include the following (adapted from PMBOK, 2013):

■ negotiating with operational managers to release or share resources for the project (this may also involve allocating a percentage of their time and cost)

■ investigating prevailing market conditions for availability and commercial rates for contractors

■ reviewing preferred supplier arrangements should these resources be used again

■ communicating potential consequences to stakeholders for failing to acquire the necessary resources (this may include scope, schedule, cost, risk and quality variations impacting client acceptance, project success and/or outright cancellation)

■ evaluating potential resources against the ambit of legal, regulatory, mandatory and/or other specific criteria covering their assignment

■ considering the professional development plans for the nominated resources and how this time and cost will be addressed by the project budget

■ factoring in the challenges of managing resources collocated in multiple locations, each with different time zones and communication protocols

■ determining how performance throughout the project will be measured and evaluated

■ reflecting on the manager’s ability to manage a group of diverse resources brought together for a finite time span.

The issue of diverse resources is paramount. With the project resource pool spanning the Traditionalists (‘silent generation’), Baby Boomers (‘Wrinklies’), Generation X, Generation Y and Generation Z (or ‘Next’ or ‘Millennial’), managing diverse project teams involves working with resources that are both diverse and ageing. With the majority of workers now 45 years and older, organisations need to hire, train and retrain people, while also retaining older workers (Cole 2010). With more than mere muscle tone and wrinkles fuelling the generational gap, the marked attitudinal differences between these generations often create potential problems in understanding each other (different attitudes, expectations, beliefs, motivation and skill sets), in dealing with issues and conflicts constructively, and in appropriate responses to behavioural performance problems as they arise. As Cole (2010) suggests, ‘The better you understand the combination of factors that motivates and drives each generation, the better you can lead them.’

Let’s review three of these generations, looking for ways in which the project organisation and project manager can bring together (and manage) a resource pool that develops courage, commitment and performance. Table 8.1 summaries some of the key characteristics for each generation, drawn from Cole (2010) and Kane (adapted from online resources).

With such a diverse multi-generational pool of resources, along with the flexibility of working conditions of the modern era (full-time, part-time and contract positions), project managers will need to ensure that everyone is task-ready to carry out their allocated activities. The following suggestions might help to get the best out of everyone involved:

■ Demonstrate empathy (where you genuinely can—this should never be faked).

■ Encourage continuous, open and honest feedback.

■ Give everyone an opportunity to ‘shine’ in what they are good at.

■ Identify what the common ground is.

■ Praise the effort, not just the result.

■ Avoid rushing in to rescue.

■ Don’t over-stimulate, as boredom often leads to imagination.

Table 8.1 The multi-generational project team

| Baby Boomers (1946–64) | Generation X (1965–80) | Generation Y (1981–95) |

|---|---|---|

| Live to work | Work to live | Work–life balance |

| Focused on position and prestige | Dislike routine | Respond to a sense of purpose and achievement |

| Defined by professional accomplishments | Well educated | Enjoy working with supportive management |

| Critical of gen X and gen Y work ethic | Independent, resourceful and self-sufficient | High positive self-belief |

| Confident, self-reliant | Value freedom and responsibility | Expectations of continuous and positive feedback |

| Strive to make a difference | Casual disdain for authority | Avoid following the traditional chain of command |

| Competitive in the workplace | Detest structured work hours | Excellent grasp of technology platforms |

| Believe in hierarchical structure, rank and power | Prefer hands-off management style | High education completion rate |

| Practise ‘face time‘ in the office | Comfortable with technology | Comfortable with change |

| Well established in their careers | Willing to change jobs for career advancement | Drivers of innovation |

| Loyal and cynical | Ambitious and eager to learn | Peer acceptance and recognition is important |

| Independent | Enjoy fun in the workplace | Socially conscious and environmentally aware |

| Not afraid of confrontation | Not intimidated by authority | Value corporate social responsibility |

| Resourceful and clever | Free agents | Sense of entitlement |

■ Develop capacity, not dependency.

■ Provide an environment where continual learning is encouraged.

■ Provide choices and pathways.

■ If mistakes are not terminal, focus on the lessons learned.

■ Focus on the project’s objectives (output and outcomes).

■ Call for volunteers (where you can, as opposed to always allocating jobs).

■ Be aware of personal differences.

■ Focus on skills, not age.

■ Develop appropriate recognition and reward programs.

■ Facilitate meet and greet sessions (off site).

■ Initiate a mentoring program.

Given that a number of key decisions will end up being made around resource capability, availability, experience, cost, attitude and other unique human factors, is this all that is required to bring resources together? Or is resource acquisition only a stepping stone to a bigger challenge—that of developing the project team? With predefined roles, known abilities and scheduled activities, many would think the hard work is over. Think again!

Henry Ford once said, ‘Coming together is a beginning; keeping together is progress; working together is success.’ His words provide an enlightened insight into the machinations of teams (and those who pretend to be part of teams). Perhaps the key word in his quotation is ‘together’, and the reason should be clear. When a group of people first come together under the project umbrella, are they:

■ really a team or a group of individuals occupying the same floor space

■ committed to the team (and the project objectives)

■ able to nominate/elect/support/follow a leader

■ clear about their specific roles

■ ready to share their ideas

■ ready to work together

■ open to constructive feedback

■ prepared to help each other?

The answer is ‘possibly not’ to many (if not all) of these questions. So what exactly is a team: what does it look like and how does it function? Perhaps the following characteristics (often used to describe a high-performing and conforming team, which is held up as the ideal) can be used as a guide. A team has:

■ clear, communicated and recognised long-term goals

■ clear, communicated and accepted objectives

■ unqualified opportunities for success

■ a tolerance for calculated risk

■ mutual appreciation of members’ individual and broad skills

■ defined, communicated and accepted roles

■ explicit, discussed and endorsed procedures

■ open, honest and continuous communication

■ supported leadership

■ a commitment to delegation and accountability

■ ongoing access to constructive feedback and support

■ appropriate, tailored and timely rewards

■ opportunities for regular performance reviews.

You may be familiar with terms like ‘dead wood’, ‘oxygen thieves’, ‘chair warmers’ or ‘whingers’. Sadly, terms like this can categorise the type (and standard) of human resources engaged in the project—just as easily as ‘champions’, ‘advocates’, ‘supporters’ and ‘volunteers’ can. In fact, one of the most frequent complaints issued by project managers from in-house projects is that they often cannot hand-pick the team they need, as they invariably inherit the established team or at least the key team members. Best practice would dictate that team members are recruited (either formally or informally) in line with the project’s initial objectives, agreed deliverables and ultimate success criteria. The following may serve as a useful guideline. Team members should have:

■ the technical competence required to perform the assigned work (or the ability to acquire this competence)

■ commitment to the project’s goal

■ the ability to work with, respect and trust other team members

■ demonstrated communication skills, particularly in issuing instructions, conducting meetings, resolving conflicts and writing reports

■ the ability to identify key issues, solve problems and implement the solution (while still being a team player)

■ the ability to work without constant or ongoing supervision

■ experience and knowledge of project methodology

■ the availability (time) to give to the project

■ the consent of their operational managers (if in-house).

So let’s get a positive out of inadvertently categorising resources with potentially unfair or discriminatory labels. Drawing on the DiSC® personality assessment, Cole (2010) suggests that another form of classification may be more appropriate when looking to maximise the different personalities and unique attributes that resources bring to a team environment:

■ conscientious thinkers: the detailed, checking, accurate, time management type

■ dominant directors: the focused on the end-game results type

■ interacting socialiser: the fun, enthusiastic, spirited and energetic type

■ steady relaters: the patient, willing, reliable and cooperative type.

Regardless of the classification used, the project manager will need to bring out and showcase the differences everyone has, and use those differences to build the team.

Valuing project team diversity

Project teams will consist of unique individuals drawn from a very diverse demographic pool. With these differences will come the need to acknowledge, understand and value these differences in the composition of your project teams, through respecting and harnessing those differences to deliver the project.

However, Gido and Clements (2015) point out that diversity can also generate different outcomes around mistrust, misunderstanding and miscommunication (to cite a few examples), leading to low morale, increased tension, suspicion and distrust, reduced productivity and a growing impediment to team performance. By refusing to embrace diversity through creating a shared sense of belonging and feeling valued, project teams can miss out on the unique ideas, perspectives, experiences and values that people from different ethnic backgrounds can bring to the project.

Valuing diversity creates an inclusive environment, which promotes equality, values diversity and maintains a working (and social) environment in which the rights and dignity of all team members are respected. So what might diversity look like in your project environment? Consider the following suggestions (and feel free to add to this list):

■ Ethnicity: different cultures may require their members to be tolerant and patient in the customs and behaviours shown by and to immigrants and/or their descendants. Language proficiency may also be a factor.

■ Age: different age groups bring different experiences, expectations, values and perspectives.

■ Appearance: facial features, tattoos, weight, jewellery and clothing (as examples) should not cloud assumptions about performance or competence.

■ Gender: non-discriminatory recruitment practices need to be followed.

■ Sexual orientation: an inclusive and diverse working environment should be created that encourages a culture of respect and equality for everyone, regardless of their sexual orientation or gender identity.

■ Health: physical mental and/or behavioural abilities will need to be accommodated and not used to discount real or potential capabilities.

■ Status: marital and/or parental status should not fuel assumptions about availability or competency.

■ Religion: religious practices need to be respected and accommodated.

Critical reflection 8.2

It is important that project teams do not exclude or lower their expectations of certain diverse groups, as differences do not imply inferiority or superiority.

■ Identify ways in which diversity can be encouraged and actively supported in your project.

■ What benefits would this inclusive practice deliver to your project?

Teams and their evolution

It is now time to examine, in some detail, a few of the more common and prevalent ‘team issues’ (and problems) that can impact on the team’s ability to deliver its assigned performance throughout the project. In a project, a number of individuals may come together under a common purpose (ideally) to form a team. Teams do not develop by themselves, though; nor do they remain energised, motivated, committed or ‘pumped’ by themselves. What does happen is that newly formed teams develop and evolve through a largely predictable cycle or stages of development on the road to maturity.

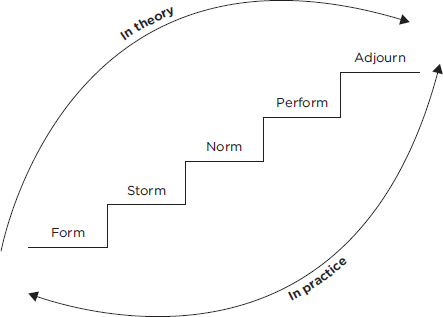

Tuckman (1965) proposed a model that is still endorsed today. It tracks the development of a team over five predictable stages, with the attainment of each level of development triggering each subsequent level. At each level, there are different characteristics, issues and pressures on the team members that must be managed skilfully by the project manager if the team is ultimately to perform its tasks. Table 8.2 outlines the five stages of team development, the more salient characteristics of each stage and the key tasks the project manager will need to action to ensure the team develops and reaches the required level of maturity (adapted from Cole, 2010; Tuckman, 1965 and others).

These different stages do not just happen—they have to be managed not only by the team leader and/or project manager, but also by all the team members themselves. Few teams, if any, perform effectively from day one—or overnight—and continue performing. Their evolution must be guided, instructed, coached or even redirected at times. Nor is their (implied) sequential development a given, as the team can fracture at any of the five stages. Should this happen, development will often revert to an earlier stage to enable the issues to be satisfactorily readdressed before development and performance continue, as reflected in Figure 8.1.

In essence, each team member must be a known capability and be made to feel valuable—they must see that they have an important role to play and that they will actively contribute and be involved in the project. Everyone involved will have a significant impact on the whole project—from concept to finalisation—and they may need to be guided, instructed, coached or redirected. While much has been said of the need for the team to evolve into a highly performing and conforming entity, there are disadvantages as well as advantages when using teams on a project (see Table 8.3).

Given the ongoing prevalence of teams and their known disadvantages, here are a number of timely suggestions for improving project team effectiveness:

■ Control the loud, the dominant and the opinionated, who often quash the passive, less confident and perhaps inexperienced team members.

■ Encourage the quiet and silent members to voice their opinions in a nonthreatening environment.

■ Protect the weaker members from ridicule, recrimination and destructive criticism.

■ Wherever possible, close on a positive note that recognises achievement, performance or contribution.

■ If required, address the most senior people last to limit their input, direction and influence on other (easily led) members.

■ Encourage the constant cross-fertilisation of ideas, alternatives and discussions.

■ Practise honesty, respect and integrity in all the team pursuits.

Table 8.2 The five stages of team development

| Stage | Characteristics | Required actions |

|---|---|---|

| Forming |

■ A room full of strangers ■ Obligatory introductions (attempts to ‘break the ice’) ■ Little common understanding (ambiguity in both goal and role) ■ Personal feelings are a priority ■ Low or absent group identity ■ Impersonal, polite and careful conversations (caution, anxiety) ■ Tentative relationships (little trust, hidden agendas, initial pecking order) ■ High need for approval ■ Dependent on leadership for structure and guidance |

■ Facilitate the ‘meet and greet’ ■ Build a common goal ■ Understand and moderate personal expectations ■ Clarify roles and responsibilities ■ Assess and acknowledge individual capability ■ Practise directive leadership for both objective and process |

| Storming |

■ Inevitable and natural conflict (personality, role or leadership clashes) ■ Cliques may form and silos be established ■ Power struggles and ‘turf’ wars develop ■ Exploration of values, working styles and aims ■ Disillusionment and frustration may surface |

■ Practise open communication, where everyone has a valid opinion ■ Enable issues, differences and conflict to be discussed and resolved ■ Re-clarify goals and roles ■ Discuss the project work and project management approach ■ Encourage collaboration |

| Norming |

■ Codes of acceptable behaviour, rules, customs and policies established ■ Work rhythms established ■ Close relationships develop ■ Renewed sense of hope ■ Individual difference accepted and appreciated ■ Trust and openness develops ■ Emerging team identity |

■ Encourage forums, workshops and other avenues to share information ■ Create appropriate feedback loops ■ Practise principled negotiation where required ■ Collate and circulate team rules ■ Revisit individual, team and task expectations ■ Discuss the technical decisions involved in completing the work |

| Performing |

■ Synergy, creativity and harmony develop ■ Close working relationships (independent, together or other combinations) ■ Balanced productivity (task) and cohesion (process) ■ Continuous improvement and innovation ■ Resolution of internal disputes ■ Strong team spirit (trust, open communication, resourcefulness) ■ High team autonomy and maturity |

■ Appraise performance and results against the project plan ■ Recognise and reward success ■ Sustain the close relationships within the team ■ Encourage initiative and innovation ■ Practise delegation where appropriate ■ Ascertain whether the team’s efficiency and effectiveness can be improved |

| Adjourning |

■ Project objectives realised ■ Performance is evaluated ■ Achievement is celebrated ■ Impending sense of loss of (team) identity ■ Team disbands and resources are redeployed |

■ Ensure all project objectives have been met ■ Celebrate performance and results ■ Reassign resources ■ Document the lessons learned ■ Close out all processes ■ Allow time to mourn |

Figure 8.1 Stages of team development

Table 8.3 What teams do and don’t deliver

| Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|

|

■ Greater knowledge and information sharing ■ Different approaches to the problem ■ Increased acceptance of the solutions ■ Better comprehension of the decision ■ Opportunities to match people’s abilities with those of others ■ The synergy displayed by the individual contributions ■ Shared achievement ■ Cross-fertilisation of ideas ■ Equal sharing of the workload |

■ Premature decisions ■ Individual domination ■ Conflicting alternative solutions ■ Prior commitments ■ Time taken to make decisions ■ Time taken to implement the decisions ■ Too many places to hide ■ Delays in organising and attending meetings ■ Domination by strong personalities |

■ Listen attentively (and completely) until you experience another person’s point of view.

■ Communicate your views assertively, free from guilt and aggression.

■ Closely examine your own motives (and those of others) within the team.

■ Be committed to resolving conflicts as soon as they have been identified.

■ Actively participate in meetings that are well managed and ultimately effective—that is, an outcome is reached.

Remember that the team members will need to feel a sense of personal achievement, accept responsibility for the work, make their own decisions in their delegated area and feel that their efforts are genuinely appreciated.

While the project manager may well carry much of the responsibility for making this happen on an ongoing basis, Kloppenborg (2015) proposes a dozen ground rules to further facilitate their development, six of which are relationship based and the remaining six process based, as depicted in Table 8.4.

Critical reflection 8.3

It is often stated that teams do not develop naturally; they have to be skilfully designed and executed if they are to perform as required.

■ What words (good or bad) would you use to describe your current project team?

■ What has led to the team being described in this way, and what impacts does this have on your project?

■ What is needed to reinforce or address the behaviour you have noted and what impacts would this have on your project?

A team that works well together will never be a chance event. With the explosion of multi-generational teams, globalisation, the information era, virtual teams and workplace and organisational diversity, the increased interdependence of different work teams, and the uncertainty of team members’ respective roles, project managers and team members must work together more effectively to align information and people if team goals are to be achieved. One of the most popular instruments to help team members align themselves is the Myers-Briggs Type Indicator (MBTI®) personality inventory, which describes the valuable differences between normal, healthy people. After more than 40 years of development, it is one of the most widely used psychological tools in the world today. It offers insight into how each person’s individual preference can be used to help the team to work more productively to accomplish common goals, and will often explain much of the misunderstanding and miscommunication between people.

| Relationship ground rules | |

|---|---|

| Encourage participation | Being prepared to be both a leader and a follower (at times) and ensuring everyone has, and can use, their voice and their ears. |

| Discuss openly | Avoid the cone of silence, secret squirrel societies and other rumour- and gossip-promoting devices. |

| Protect confidentiality | Be aware of sensitive issues and the rights of others, both under legislation and within the team expectations. |

| Avoid misunderstandings | Active listening and questioning techniques will reduce the likelihood of information being distorted or deleted, and provide the opportunity for everyone to be on the same page. |

| Develop trust | Trust doesn’t develop naturally, so team members must be open, honest and transparent with each other if respect and trust are to be developed and maintained. |

| Handle conflict | Is it conflict or is it creative discussion, a personal attack or something more destructive? Remain neutral and encourage an exchange of ideas without fear or favour. |

| Process ground rules | |

| Manage meetings | Have a reason for meeting, and know what the process will be, what has to be covered and what decisions are required. |

| Establish roles | Everyone needs a role and the necessary delegation of responsibility that goes with the role. A role is much more than just a title, so get the team members talking broadly about their role. |

| Maintain focus | Projects have a lot going on all the time, so focus, motivation and performance can begin to wane over time. Reaffirm the project objectives, deliverables, methodology and performance against the plan. |

| Consider alternatives | While no one wants unbridled dissent, putting forward options, alternatives and ideas is a great way to explore different ways of doing things. People contribute and feel valued, and authorised changes might be allowed. The sense of ownership this creates is priceless. |

| Use data | Information exists to be used, not just archived in boxes. Focus on the facts, not the fiction, and communicate how the information was used to make different decisions. |

| Make decisions | In the absence of decisions, not too much happens. So in order to maintain momentum in both the team and the project itself, timely decisions will need to be made, communicated and perhaps even ‘sold’ to the team. |

Source: adapted from Kloppenborg (2015)

The profile may help to uncover the team members’ strengths and unique gifts, their influence on other team members, how each member can contribute to team functioning and their individual ability to maximise team effectiveness. It is also useful as a self-affirming tool, while also enhancing cooperation and productivity (not to mention the way some team members can often annoy and irritate each other). The MBTI reports your preferences on four scales, each consisting of two opposite poles, as depicted in Table 8.5, along with the common characteristics of each type (adapted from Briggs Myers, 1997; Hirsh, 1992).

So how does all this information help with accepting people’s unique differences in project teams? See whether you know people who:

■ are constantly late, absent, or present but not participating

■ are unprepared and don’t follow up on tasks

■ are direct in dealing with everyone

■ are distracted by the lack of immediate results

■ complain, whine and negate everything

■ interrupt and talk too much

■ are overly emotional

■ get off the track easily

■ lack common sense

■ play the devil’s advocate

■ waste time and talk abstractly.

| Focusing your attention | |

| Extroversion (external) | Introversion (internal) |

|

■ Breadth of interests ■ Speaks first, reflects later ■ Social and expressive ■ Communicates by talking ■ Takes the initiative ■ Learns by doing ■ Enjoys working in groups ■ Extends into their environment ■ Shares thoughts freely |

■ Has depth of interest ■ Reflects before speaking or acting ■ Private and contained ■ Prefers written communication ■ Readily focuses ■ Learns by reflection (mental practice) ■ Enjoys working alone ■ Defends against external demands ■ Guards thoughts until (almost) perfect |

| Taking in information | |

| Sensate (practical) | Intuitive (creative) |

|

■ Focus on what is real and actual ■ Values practical applications ■ Has an interest in facts, concrete information ■ Remembers sequentially ■ Lives in the moment ■ Likes step-by-step instructions ■ Trusts experience ■ Seeks predictability ■ Sees difficulties as problems to overcome ■ Follows the agenda |

■ Focuses on possibilities (what might be) ■ Values imagination and insight ■ Has an interest in abstract, theoretical concepts ■ Sees patterns ■ Lives in the future ■ Prefers to jump around ■ Trusts inspiration ■ Desires change ■ Sees difficulties as an opportunity to explore ■ Departs from the agenda |

| Making decisions | |

| Thinking (objective) | Feeling (subjective) |

|

■ Analytical ■ Logical problem-solver ■ Cause–effect reasoning ■ Tough-minded ■ Prefers impersonal, objective truth ■ Reasonable and fair ■ Controls expression of feelings ■ Wants things to be logical ■ Questions first |

■ Sympathetic ■ Assesses impacts on others ■ Driven by personal values ■ Soft-hearted ■ Promotes harmony and compassion ■ Accepting ■ Openly expresses feelings ■ Wants things to be pleasant ■ Accepts first |

| Orientation to your environment | |

| Judging (logical) | Perceiving (flexibility) |

|

■ Scheduled ■ Organised ■ Systematic ■ Methodical ■ Likes to plan ■ Priority is closure ■ Avoids last-minute change and stress ■ Finishes tasks before deadline ■ Prefers to be conclusive ■ Focuses on results, achievements |

■ Spontaneous ■ Fluid ■ Casual ■ Flexible ■ Adaptable ■ Open to change ■ Energised by last-minute pressure ■ Finishes tasks right on deadline ■ Prefers to be tentative ■ Focuses on options, openings |

What about the great contribution the very same people can make through offering systematic, practical perspectives; creating morale, unity, harmony, energy and excitement; asking questions others don’t want to ask; providing ideas and insights; seeking unique possibilities; and being empowering and inspiring? While numerous different ‘versions’ of the MBTI profile (and other profiling instruments, inventories and tests) are now commercially available, it will still enable all team members to understand:

■ their natural preferences for focusing their energy, gathering information, making decisions and living a certain way

■ their preferred way to respond to team challenges

■ their style of interacting and communicating with others on the team

■ the unique way in which each member makes a distinctive contribution to the team

■ ways of reducing unproductive work

■ areas of strength and possible areas of weakness for the team

■ how to clarify team behaviour

■ how to match specific task assignments with team members according to their preferences

■ how to identify which team members handle conflict better

■ how different perspectives and methods can lead to effective problem-solving.

Finally, Robbins and Finley (1999) propose a version of the ten commandments for working in teams. These have been amended and updated (three have been added) to reflect the changing dynamic behind project teams:

1 Never create a team unless the task requires a team.

2 A team shall have only one primary goal.

3 When the goal is accomplished, the team should disband.

4 Disband the team when policies and procedures for which they were responsible have served their purpose.

5 People who do not wish to participate in the team should resign or be removed.

6 All members are leaders who must lead if the leader is not leading.

7 Keep the enemy outside the team.

8 Differences of opinions are to be encouraged.

9 When you break your word, trust will be ten times harder to rebuild.

10 Open up the channels of communication and information.

Critical reflection 8.4

Everyone has a personality. Sadly this doesn’t mean we all get on well and appreciate the unique differences each personality offers when we work together.

■ Do some additional research into profiling tools: MBTI, DiSC, Belbin® team Roles and others.

■ What have you learnt about your personality—the bits you like and perhaps the bits you don’t?

■ In understanding more about personality, how has your impression of others changed (if at all)?

■ What will an understanding of your own and others' personalities bring to the project team and the ultimate success of the project?

Learning and development for teams

The explosion of the internet, the flexibility now required in the workplace and the generational changes in learning have all driven changes to the training and learning environments and to the array of available professional development pathways and delivery modes.

Now, more than ever, there is a need for resources to be able to learn, unlearn and relearn—and not just the technical knowledge that so often prescribes their position description. The pool of knowledge, skills, insights, experience and information held by the team will need to be tapped into and developed throughout the project. And learning shouldn’t be limited to just plugging the gaps, as it should also be about ‘strengthening existing skills, identifying development opportunities and developing people for the future’ (Cole 2010).

With learning no longer limited to traditional delivery modes, personal, business, interpersonal or technical skills can now be addressed through any of the following:

■ taking on projects

■ online learning

■ coaching

■ webinars

■ formal study

■ job rotation

■ distance learning

■ internal courses

■ mentoring

■ seminars

■ private research

■ observation

■ professional reading

■ acting in higher positions

■ committee work

■ shadowing

■ delegated duties

■ discussions

■ work experience

■ special assignments

■ on-the-job experience

■ peer-assist programs

■ professional memberships

■ role models

■ conferences

■ evening classes

■ simulations.

Clearly, projects themselves are a form of professional development for many of those involved in them. In some cases, learning opportunities are limited, as it is believed that all the pre-existing operational expertise people possess will automatically be applicable and transferable to the project. To ensure that this learning opportunity is not lost, consider the following questions that could be asked by the project manager:

■ How well have I understood the team’s skills, knowledge and abilities?

■ How have I assisted the team to sustain and develop these?

■ How do I allow the team members to practise what they have learned?

■ How do I encourage the team member to share what they have learned with others?

■ How do I create an environment that enables the team to create and innovate?

■ How do I encourage the team members to contribute to their maximum potential?

■ How do I model the appropriate behaviour and actions that I want the team to develop?

■ How do I demonstrate that I value the team’s opinions?

■ How do I encourage the team members to learn from their mistakes and to help others learn from theirs?

■ How do I regularly assess the team’s competence?

Be wary, as training and learning regimes should not always be the default solution (ideal or otherwise) on everyone’s ‘to do’ list. Obviously, a lack of motivation, outdated and inadequate equipment, resource scarcity, personal crisis or resources ill-suited to the role to begin with would not be addressed by enrolling them in a training course.

The complex nature of the project resource pool requires project managers to effectively manage (and lead) traditional and non-traditional teams—merged, matrix, mixed and virtual teams—along with volunteers, casuals, contractors and part-timers. Effective management requires performance management to align the organisational project goals with the goals of the team members, and conflict management to deliver greater productivity and positive working relationships.

The innate driving force

All human behaviour and performance start with some form of internal detonation called motivation. People act the way they do because they are motivated to do so. However, it is impossible to motivate someone unless they want to be motivated. That is, all motivation is self-motivation and comes from within. It is an innate driver within each team member that is much like the ignition key on the car—it triggers action, the car starts and performance (safe motoring) follows.

Motivation is the force acting on or within an individual that will cause that person to behave in a specific, goal-directed manner. The motivation that drives a project team will affect their performance and productivity within the project, their ability to achieve the project’s deliverables and other related goals. Project managers are held responsible for completing a project; however, a manager alone cannot complete the task—it will require the sustained and committed efforts of the team members. What the manager must do is provide the environment that will allow (and stimulate) the team members to contribute their best efforts to the project. This is the challenge of motivation. Within the team, their collective motivation will:

■ energise the team members to complete their scheduled work (on time, on budget, as specified)

■ direct the team towards meeting deadlines, milestones and other constraints

■ draw the team together cohesively

■ enable the team to function in self-directed mode

■ allow the team members to self-correct much of their own work.

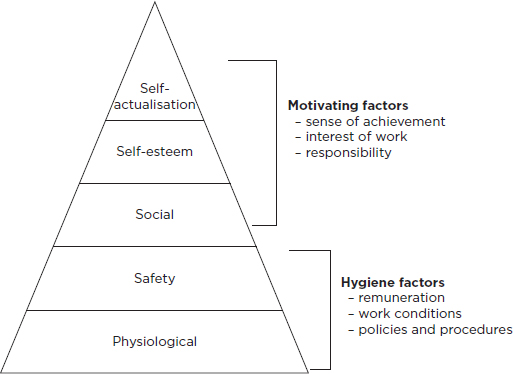

Everyone has a favourite theory of motivation. Two of the frequently cited examples are Maslow’s hierarchy of needs model and Herzberg’s motivators and hygiene factors. Both are expanded upon in Table 8.6. Irrespective of which model you embrace, the key learning should be that the project team must work within an environment that allows for motivation. Be it a hierarchy of needs, internal work factors or external factors impacting on the team’s satisfaction, the project manager must ensure that all avenues are actively pursued in order to motivate the team.

As organisations continue to restructure, downsize and increase the loading of their resources across both operational priorities and project work, motivation cannot be ignored—regardless of which theory is espoused. Figure 8.2 overlays both theories. Yes, you can buy their time on an hourly basis, but you cannot buy ‘their enthusiasm or loyalty, the devotion of their hearts, their minds and souls’ (Cole 2010). It is only through motivation that resources will be engaged (and not just satisfied) and productive in the workplace.

Critical reflection 8.5

Everyone these days has a theory about motivation, although I admit my preference for the earlier work of both maslow and Herzberg, both of whom offer practical insights into what our motivations are.

■ A simple question to start with: What motivates you in your current project role?

■ How do the people to whom you report know this is what actually motivates you?

■ Now look at the people you (might) manage and ask yourself the same questions you just answered.

■ What is the key to discovering someone’s true motivation.

■ How difficult is it to match rewards to motivation in every case?

Measuring team performance

Underpinning this management is a formal or informal process of deliberate and systematic measurement, assessment and feedback aimed at building performance, motivation and work satisfaction—in other words, a conversation discussing performance, and potential and professional development opportunities. By encouraging frank, open and honest discussion, realistic expectations can be negotiated, questions answered, doubts resolved and a pathway for continued learning and development agreed to.

With the focus on developing and sustaining peak performance, team performance assessments ‘are expected to increase the team’s performance, which increases the likelihood of meeting project objectives’ (PMBOK, 2013). While project performance could be assessed against any number of traditional organisational performance criteria (key performance indicators), within the project context these should be extended to include a number of results-oriented and agreed upon criteria, including:

■ performance against the objectives

■ performance against the schedule

■ performance against the budget

■ performance against the scope.

Table 8.6 Theories of motivation

| Maslow |

This model suggests that motivation exists on five different levels, with each level being a prerequisite for the next—that is, a bottom-up hierarchy of needs in which the lower level needs must be satisfied before the higher level needs. There are five different categories of needs that all individuals seek to satisfy. These are (starting at the bottom and with a few examples): 1 physiological (e.g. air, water, sex) 2 safety (e.g. shelter, clothing) 3 social (e.g. interactions, memberships) 4 self-esteem (e.g. ego, self-worth) 5 self-actualisation (e.g. autonomy, independence). |

| Herzberg |

This model examines the relationship between job satisfaction and productivity. It claims that some job factors lead to satisfaction (and increased productivity), while others can only prevent dissatisfaction (and lower productivity). It also argues that job satisfaction and dissatisfaction do not exist on a single continuum—that is, it is possible to be satisfied and dissatisfied at the same time. The model pivots around two central categories. Hygiene relates to factors external to the job or work, which parallel maslow’s lower level needs (physiological, safety, social): ■ company policies ■ administration processes and procedures ■ remuneration and other benefits ■ working conditions ■ interpersonal work relationships. Motivators relate to internal factors directly associated with the job itself, which parallel maslow’s higher level needs (esteem and self-actualisation): ■ the nature of the work itself ■ acting in another capacity ■ challenging work ■ recognition ■ feedback ■ advancement ■ acknowledgement ■ work variety ■ responsibility. |

Figure 8.2 Overlaying maslow’s and Herzberg’s theories of motivation

With some projects having a short life-cycle, the opportunity for the project manager to conduct a performance review is often not viable. In these cases, the operational manager must be made aware of the performance and development of staff throughout the project. Equally, on longer projects, project managers may not think that such a review is necessary, or even part of their own position description—so again the opportunity is lost, with everyone relying on the operational manager’s prescribed responsibility to conduct the performance assessment and review.

Research has confirmed two significant trends regarding project-based work and performance. First, there is a clear move from functional-based work to project-based work in organisational contexts (Baker 2013). In practical terms, this means that managers are more inclined to organise work around cross-functional projects rather than functions. This shift has resulted in matrix organisational structures. Project capabilities are therefore becoming more valued in the workplace.

The second conclusion is that performance management is being perceived as an ongoing process rather than being considered a once- or twice-a-year event. In other words, the performance appraisal is under critical review and is not valued to the same extent as it was in the twentieth century. This means that performance management ought to be a seamless process based on a series of short, focused conversations. Managing performance has moved from an evaluative process to one of employee development.

Consequently, with more project-based work and a shift to a developmental approach to performance management, project leaders need to put structured performance systems and processes in place. In practical terms, this means people’s project performance is an ongoing concern and not an episode conducted at the conclusion of the project. This implies that project leaders should be skilled in initiating timely and constructive dialogue with project members and stakeholders about performance. These performance conversations are often neglected in order to meet ambitious project management milestones.

There are numerous definitions out there for what performance management is and is not. In the context of project-based work, performance management is a process for establishing a shared understanding about what is to be achieved in the project. It is about aligning the project objectives with the project members’ agreed measures, skills, competency requirements and development plans, and with the delivery of results. The emphasis is on improvement, learning and development in order to achieve the overall project strategy and to create a high level of performance.

Baker (2013) proposes a new approach to performance management, referred to as the five conversations framework. The framework is based on five conversations over the course of five months between the project manager and their staff. This framework is outlined in Table 8.7.

Each conversation, lasting no more than 15 minutes, has relevance for project work. The climate review conversation can provide a temperature gauge for where project members are at and any remedial action that can be taken to improve satisfaction, morale and/or communication. Project managers can utilise the strengths and talents conversation to determine the extent to which peoples’ skills are best being utilised in the context of the current project. Conversations on opportunities for growth can consider areas that need developing. The learning and development conversation considers ways and means of assisting project members to capitalise on their talents and overcome their limitations. Innovation and continuous improvement conversations are designed to bring to the surface ideas for enhancing the project and all its components. Together, the five conversations are an effective performance-development methodology for project managers.

Table 8.7 The five conversations framework

| Date | Topic | Content | Key questions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Month 1 | Climate review | Job satisfaction, morale and communication |

■ How would you rate your current job satisfaction? ■ How would you rate morale? ■ How would you rate communication? |

| Month 2 | Strengths and talents | Effectively deploying strengths and talents |

■ What are your strengths and talents? ■ How can these strengths and talents be used in your current and future roles in the organisation? |

| Month 3 | Opportunities for growth | Improving performance and standards |

■ Where are there opportunities for improved performance? ■ How can I assist you to improve your performance? |

| Month 4 | Learning and development | Support and growth |

■ What skills would you like to learn? ■ What learning opportunities would you like to undertake? |

| Month 5 | Innovation and continuous improvement | Ways and means to improve the efficiency and effectiveness of the business |

■ What is one way you could improve your own working efficiency? ■ What is one way we can improve our team’s operations? |

Source: Baker (2013).

How hard can it be to have a conversation with a team member—to show an interest in their past performance, to provide constructive feedback that enables and empowers improvement and to discuss their aspirations? Is it the appraisal system (paper based or electronic) that lets everyone down? Is it the lack of management training in conducting appraisals that leads to cynicism and mutual indifference, or is it the cumbersome and time-consuming process that ticks over every six or twelve months that creates visible resentment, distrust and criticism? Perhaps it is the perceived judgemental nature of the process?

There are numerous performance management techniques available, some of which are previewed in Table 8.8. Review the list and feel free to experiment with the ones you are least aware of, or are least confident in, and take them for a ‘test drive’. And remember, each technique can play a part in improving understanding, trust, commitment and communications among management and team members, and can facilitate more productive teams throughout the project (PMBOK, 2013).

Remember that performance appraisal is carried out to provide feedback (constructive information) that will identify specific training, coaching, mentoring, assistance or changes required to improve the team’s performance—be that through personal skill development or increased team cohesion, leading to improved overall project performance (PMBOK, 2013).

Reinforcing the performance

Another related topic is rewards. Someone once said, ‘What gets measured and rewarded gets done’. Think about your project teams and the reinforcement and/or rewards they receive for performance. The following questions may help you to evaluate the suitability of your rewards:

■ Do people value the rewards (are they worth the effort)?

■ Is there equity in the rewards across the team?

■ How competitive are they?

■ Do the team members want them?

■ Have you asked the team members how they would like to be rewarded?

■ Are the right people being rewarded for the right reasons?

■ Have you considered that some good team members may be made to feel worse as a result of others receiving rewards?

■ Is the reward a ‘one off’, or is it a regular occurrence?

■ Are the rewards demonstrating ‘lazy management’?

■ Are the rewards conditional on performance, or are they a regular management practice?

■ Are the rewards handed out in a timely manner driven by task achievement, or do they exist for management’s convenience?

■ Are you rewarding success based on ability, effort, strategy, luck or task difficulty?

Table 8.8 Popular performance-management techniques

| Technique | Purpose |

|---|---|

| Structured interviews | Formal interviews with team members responding to the questions asked |

| Critical incidents | A record of both positive and negative important (critical) incidents during the review period |

| Written essays | Writing a couple of paragraphs detailing each team member’s behaviours and skills |

| Rating scales | Defined scales for each job-related skill, enabling quick comparisons between team members |

| Peer review | Team members review each other’s performance against key criteria |

| 360-degree feedback | Multi-rater anonymous feedback from people working with the team member |

| Balanced scorecard | A rating against a list of values, attributes and qualities deemed critical to success |

In some cases, reinforcement is not an automatic consideration, as the emphasis lies solely on taking corrective action through exception reporting. While performance deviations must be addressed, they cannot be focused on in isolation from other compliant performance. Nor does every deviation need corrective action. For the project manager to build and sustain team performance, they must learn (and learn quickly) how to balance both corrective action and reinforcement.

Critical reflection 8.6

Performance in a project is a given, isn’t it? So why measure and manage it? Don’t operational managers do that sort of thing?

■ Do projects require some form of performance management process? If so, why?

■ What could explain the different level of performance someone displays throughout a project as distinct from their everyday role?

■ How could you ensure that project performance is incorporated into any operational performance-review process?

In business, there will always be issues, complaints, delays, broken promises, false expectations, misinformation and misunderstandings. These will generate problems and complaints—some valid, some not. Some might get resolved, and some might not. Projects are no different. In every project, given stakeholder diversity and changing expectations, there is so much potential for conflict that many would suggest it is a growth industry. Conflict can arise from a multitude of issues, including:

■ working under extreme pressure to meet deadlines

■ mismatched task and skill sets

■ personality clashes within the team and/or with stakeholders

■ conflicting operational work priorities

■ performance issues within the team

■ feelings of role insecurity

■ degree of involvement in decision-making

■ changes to the project’s scope

■ reporting to two or more managers/supervisors

■ disagreements over alternative solutions proposed and/or actioned

■ degrees of delegation and autonomy

■ different expectations, needs and/or objectives not communicated and clarified

■ hidden agendas, self-interest and dishonesty (don’t forget these!).

Given the apparent popularity of conflict, should it be ignored? Should it be avoided at all costs? Should it be viewed as a destructive force paralysing the project’s outcomes or recognised as a way to constructively encourage and manage diversity? The answer is all of the above, because conflict can have both a negative and positive (yes, it is possible) outcome, depending on how it is handled.

For example, consider the following examples of positive outcomes:

■ exploration of new ideas

■ consideration of other people’s perspectives

■ adjustments, fine-tuning or modifications made

■ clarification of different positions and interests

■ postponed decisions (yes, this can be very positive)

■ time to reconsider, clarify and communicate a proposal to those yet to support it.

Of course, there are negative (and traditional) outcomes arising from conflict, including:

■ the breakdown in communication between project stakeholders

■ increased hostility among all parties

■ the cessation of work on the project

■ legal action taken for contract breaches

■ project personnel being replaced.

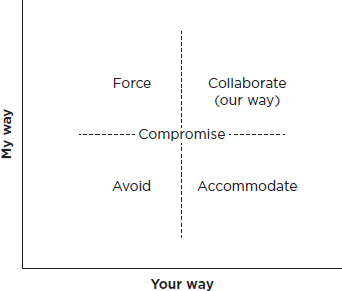

With so many opportunities for conflict during a project, a number of different and popular approaches have been developed over the years to enable conflict to be managed—if not resolved. These are illustrated in Figure 8.3 using a two-dimensional chart displaying a scale of ‘assertiveness’ orientation (an interest in your own outcome) on one axis and a scale of ‘cooperation’ orientation (an interest in the other person’s outcome) on the other.

Each of these five approaches, strategies or styles offers something different for resolving conflicts and disputes, as well as for negotiations. Using quadrant analysis, the model reflects individual behaviour in conflict situations measured across two dimensions: assertiveness (the degree to which individuals try to pursue and satisfy their own interests); and cooperation (the degree to which individuals try to pursue and satisfy the other person’s interests). At one end of the scale, you assert yourself as you compete (some would suggest force) and hold out for what you know is right (or what it is you want) with little, if any, regard for the other party involved. In other cases, your position might be more collaborative, taking both your and the other person’s positions into account with a plan to work together.

At different times, the best style may be to not engage and effectively avoid the whole issue—being neither assertive nor cooperative. And herein lies the key to addressing conflict, issues, disputes and disagreements: there is no one ‘right’ style that will work in every instance, and nor should there be, as there will always be a number of variables (e.g. time, priority, opinions, criticality of the agreement, evidence, positional power or ego) at play whenever two or more people disagree over something.

Figure 8.3 Choosing the ‘right’ conflict-management style

Now, in greater detail and with examples of when each strategy might be effective, the five strategies are: avoid/withdraw; accommodate/smooth; force/compete; problem-solve/collaborate; and compromise/reconcile.

Avoid/withdraw strategies (low assertion, low cooperation)

This strategy is neither assertive nor cooperative. No attempt is made to address the conflict at all, be it your own goals or the other person’s (also known as a lose–lose situation). An avoidance strategy may be effective when:

■ you cannot possibly win

■ the issue is relatively minor or trivial

■ it will be resolved by others

■ confronting the other party may result in more damage than resolution

■ a time-out is needed to allow everyone to disengage

■ there is an inequitable balance of power

■ more time is needed to prepare.

Accommodate/smooth style (low assertion, high cooperation)

This strategy is unassertive and cooperative. Here, the other person’s point of view is considered more important than your own (also known as a lose–win situation). An accommodating strategy may be effective when:

■ the other person’s evidence is more compelling

■ peace, goodwill and harmony are more important to the valued relationship

■ you want to create a tactical advantage by offering a concession

■ you acknowledge the weakness in your own position

■ you wish to avoid damaging the relationship further

■ emphasising common ground is more important than differences.

Force/compete style (high assertion, low cooperation)

This strategy is assertive and uncooperative. In this case, power and dominance will be often used to gain compliance to your own perspective from the ‘losing’ side (also known as a win–lose situation). A competing strategy may be effective when:

■ you know you are right

■ the stakes are too high if you lose (failure is not an option)

■ quick and decisive action is required

■ unpopular decisions have to be made

■ a show of force is required.

Problem-solve/collaborate style (high assertion, high cooperation)

This strategy is assertive and cooperative. Mutual and optimal outcomes are sought by both parties (also known as a win–win situation). A collaboration strategy may be effective when:

■ you want to build an alliance and relationship

■ you need the enduring commitment from the other party

■ you want to encourage, investigate and consolidate different perspectives

■ your solution is largely governed by the other party getting their solution too

■ you need an optimal outcome without sacrificing your own

■ multiple viewpoints must be considered

■ time is needed for open dialogue.

Compromise/reconcile style (mid assertion, mid cooperation)

This strategy combines both assertiveness and cooperation, although to a moderate or intermediate degree. Here, a mutually acceptable outcome is reached that partially satisfies both parties through each sacrificing some personal goals and issues. A compromising strategy may be effective when:

■ the outcomes are only moderately important to each party

■ no other option is working

■ the balance of power is evenly balanced

■ a gesture of ‘moving forward’ is required

■ a decision (however temporary and/or expedited) is required

■ temporary or partial resolution is acceptable.

As project manager, you will need to develop all these approaches, strategies and styles (and be able to recognise them in the hands of others) if you are going to resolve diversity, conflict and disagreements with all project team members and stakeholders. To achieve this, you will need to take into account possible anger (and the opportunity to vent that anger), burning emotional calories, frustration, irritation, upset, complaints, irrational discussions, and perhaps little or no satisfaction. Let’s not forget that these same people also want someone to understand how they feel and to try to fix their disputes and problems immediately. Perhaps the following suggestion might help to lower the temperature—particularly when the emotions are running hot. Try substituting the term ‘conflict’ with less emotive or prejudicial (and somewhat more positive) terms like ‘misunderstanding’, ‘encounter’, ‘variance’, ‘confusion’, ‘divergence’ or ‘discussion’. (Yes, they are just different words, but they also don’t carry the same emotion, positional power, vested interests or a winner–loser tag.)

So what is the best way to deal with people in conflict? Here are some guidelines (but remember, every person, situation, vested interest and desired outcome will be different):

■ Take responsibility and ownership yourself—now (do not pass the problem on to someone else).

■ Totally focus on the person and ‘actually’ listen (non-defensively, with your mind, not just your ears) to their issue.

■ Demonstrate your understanding of their issue by paraphrasing it back to them (repeating it in your own words). Make sure they have identified the real problem, and not just the symptoms.

■ Examine both the stated position (what you do hear) and the unstated position (what you don’t hear).

■ Be up front, honest and caring by apologising to the person for what has happened.

■ Use empathy to acknowledge their feelings and emotions with respect and diplomacy.

■ Outline the course of action you think will solve the problem (and be prepared to involve the person in this discussion).

■ Seek their agreement in the proposed solution (if you fail to do this, you really do not have any solution that will be effective).

■ Sincerely thank them for bringing the information to your attention (even if this one really hurts).

Critical reflection 8.7

Conflict is such a big topic. Not only can the word itself be modified to help manage conflict; this book offers some popular strategies on how to deal with all forms of conflict—both positive and negative.

■ Think about why conflict needs different strategies to respond with, and why one size doesn’t fit every conflict situation.

■ Identify what your default conflict management style is (and why you favour this) and your least preferred style (and again, why).

■ What can positive conflict bring to your projects and how can it be encouraged?

■ What can negative conflict bring to your projects and how can it be discouraged (over and above the strategies the text suggest)?

8.1 Why is HRM planning fundamental to the success of the project?

8.2 What information and decisions must be factored in to acquiring the project team?

8.3 How does the project manager help their team develop throughout the project?

8.4 Should conflict be viewed as a positive force in a project and how should it be dealt with?

8.5 What is the role of the performance review in contributing to peak project performance?

Trevor was all they had. Old school and trading on past glories with a couple of preferred suppliers (mates really), Trevor was not the ideal choice to manage this renovation project. Project management had changed from being all about technical mastery to now knowing how to manage the delivery of the project—on time, on budget and in scope. Times had changed, but sadly Trevor hadn’t.

A qualified carpenter and registered builder, Trevor had always been a ‘hands-on’ kind of guy, never afraid of getting in and getting the job done, even if it meant doing the work himself. So technically, his work couldn’t be faulted—although it was known that he sometimes took unnecessary shortcuts (which had so far not come back to bite him).

However, outside of his limited technical range, Trevor always struggled to engage, influence, direct and manage both his stakeholders and team members, as expected of a competent and practising project manager.

Trevor always struggled to engage, influence, direct and manage both his stakeholders and team members, as expected of a competent and practising project manager.

Trevor always struggled to engage, influence, direct and manage both his stakeholders and team members, as expected of a competent and practising project manager.

So leanne, the CEO of aged Care Renovations (his employer), faced a dilemma. Having just won the $800,000 contract to refurbish a residential wing at the local retirement village, she knew this project was politically sensitive, commercially crucial and community conscious, so there could be absolutely no slip-ups. Not only did Trevor need to manage the project, he needed to be the public ‘face’ of the project. As she sat in her office, leanne was hesitant to act.

Following his appointment and juggling his operational property management role, Trevor was tasked with pulling together his team for this project. With everyone literally drowning under their own operational priorities and direct reports, it proved to be an ongoing nightmare as no one really had the time, nor in some cases the skills, to take on yet another ‘conveyor belt’ project. However, with a bit of begging and pleading, Trevor pulled together something resembling a team, although it was more likely a bunch of uncommitted conscripts than a productive team.

With no recognised learning and development background (apart from his trade qualifications), Trevor failed to realise the challenge he faced in not only bringing his team together, but also identifying the assistance they would need to get ready to take on this project. While he had enrolled in different training courses over the years, Trevor’s stock-standard response to any training was that he knew everything and the trainer was an idiot who couldn’t teach him anything. Yes, Trevor certainly wasn’t the perfect role model for his team.

With marginal social skills, Trevor knew he would struggle with getting to know his team on both a personal and professional level (though he would never admit this). He didn’t really understand any of this new age ‘psycho-babble’ around personality profiles, team roles and other profiling psychometric tools, and couldn’t have cared less about getting his team to play off each other’s strengths and weaknesses.

Trevor also realised that, given the real operational and project conflicts under which his team would be working, he would have to work hard to motivate, if not reward, his team (where appropriate) through some form of performance-review process. Privately, Trevor had no idea what any of this meant or involved, as in his day you were lucky to have a job, and performance was expected if you wanted to keep your job, no matter what level it was.

As Leanne reflected on Trevor’s appointment, she realised that her own reputation and that of the company was at stake.

Questions

1 What behaviours do you think Trevor has to change and model to be an effective project manager?

2 Could an HRM plan have helped Trevor to manage, if not mitigate, the human resource issues he knew the project faced? If so, how?

3 What steps could Trevor have taken to develop his human resources (over time) into a highly conforming and performing team?

4 How could Trevor accommodate the different personalities on his team to enable them to maximise the team’s effectiveness?

5 How could Trevor identify the learning and development needs of his team to ensure they each had the prerequisite skills and knowledge to perform their project work?

6 What performance-management techniques would you recommend that Trevor adopt in measuring his team’s performance?