“This isn’t biography. It’s the only thing the English are good at… crossword puzzles.”

Alan Bennett, Kafka’s Dick

Having considered clue types and various points associated with each, we will now consider some tips on how you might go about solving them.

Seasoned solvers have many ways of uncovering a clue’s solution. The ones following are in no particular recommended order of importance, except that the first two are often quoted as ways to get started.

1. Find the definition

As you know by now, the definition part of nearly all clues is either at the beginning or end of a clue. Identifying it quickly, and assessing the definition in conjunction with word-length shown, allows the possibility of a good initial guess which can then be checked against wordplay before entry.

2. Find an indicator and/or clue type

Not all clues have indicators, as we have seen, but where they do, try to use them to identify the clue type. For example, you may spot a familiar anagram indicator such as mixed or battered and thence compare the letters in the anagram fodder with the word-length of the solution given. If they correspond, there is a good chance that you have identified the wordplay element of the clue and can develop that into a possible solution.

3. Ignore the scenario

Setters do their best to produce clues which paint a smooth, realistic picture, referred to as the surface meaning or just surface. Try to ignore it however and look at the individual components in front of you. Take the clue overleaf, seemingly about a party:

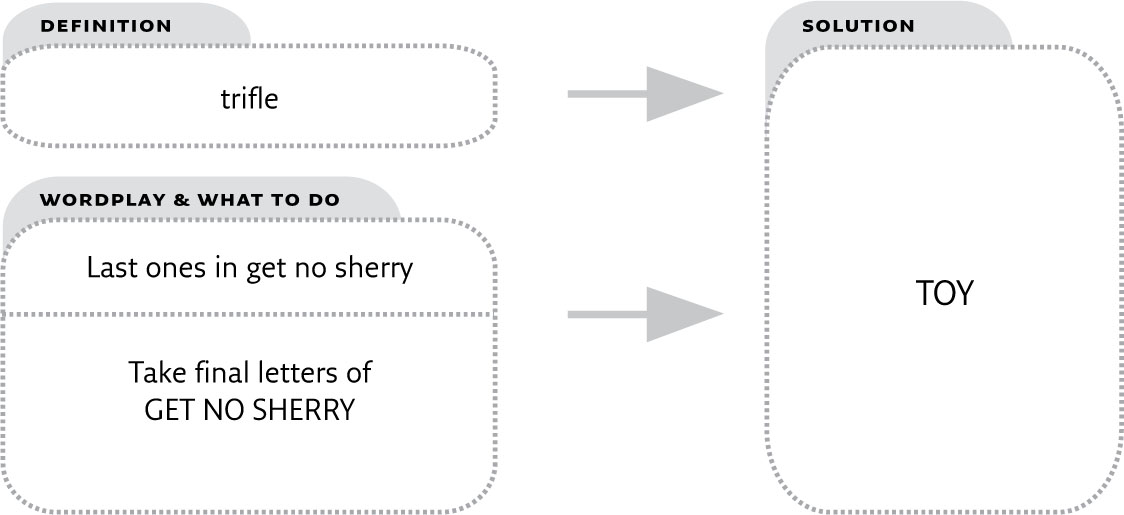

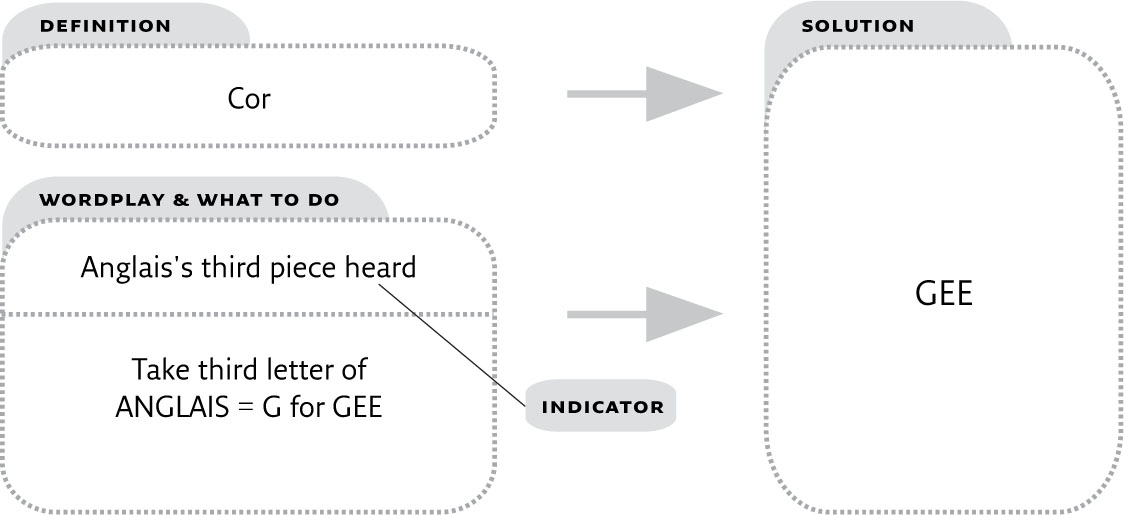

ADDITIVE CLUE: Last ones in get no sherry trifle (3)

You can be pretty sure that recalling memories of children’s parties will not be productive. It’s just a clever deception by the use of ones for letters and a letter selection indicator, last (see Chapter 3, here), leading to trifle = toy.

TOP TIP – SURFACE MEANING

The ability to look beyond surface meaning is what newbies find the hardest part of cracking a cryptic clue. My advice can only be to keep trying.

4. Exploit word-lengths

Use friendly word-lengths such as 4,2,3,4 with the central two being perhaps something like in the or of the; and 4,4,1,4 nearly always embracing the letter A, from which something like once upon a time may be the guessable answer.

5. Study every word

Consider each word carefully, separately and together. Disregard phrases which go naturally together such as, say, silver wedding, and split them into their parts. It could be that the definition is silver on its own and wedding is part of the wordplay.

In doing this, think of all the meanings of a word rather than the one that comes first into your head.

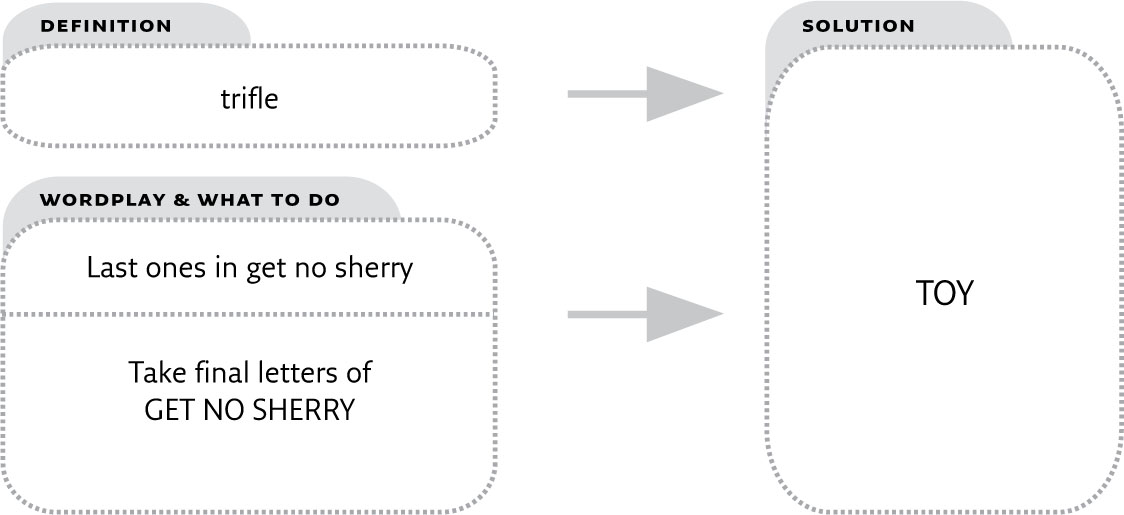

For example, forget drink in its marine sense in the next clue and switch to alcohol. The indicator some makes it a hidden clue.

HIDDEN CLUE: Some termed ocean the drink (5)

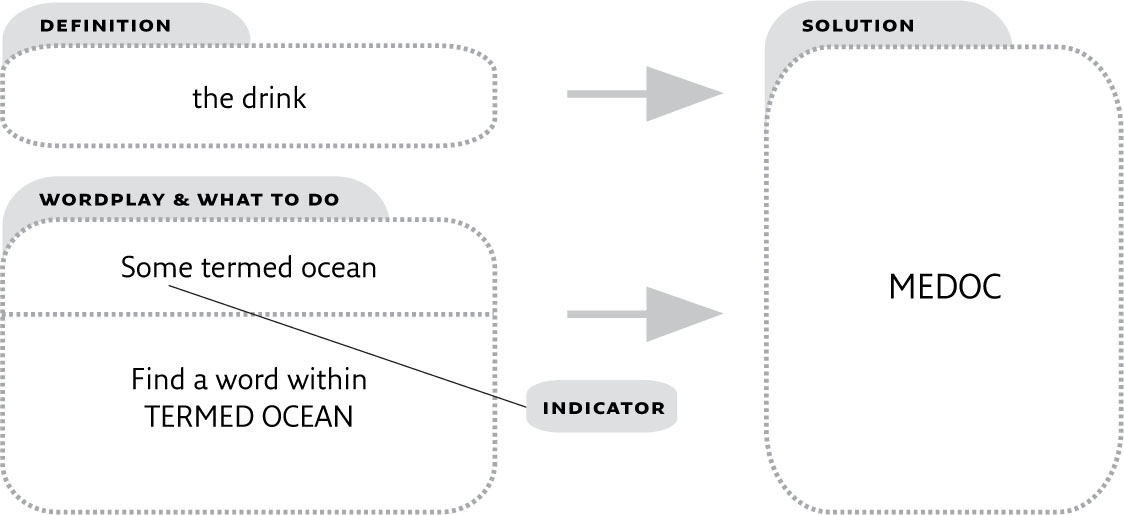

Here is another misleading image in the second example below, which has nothing to do with music:

HOMOPHONE CLUE: Cor Anglais’s third piece heard (3)

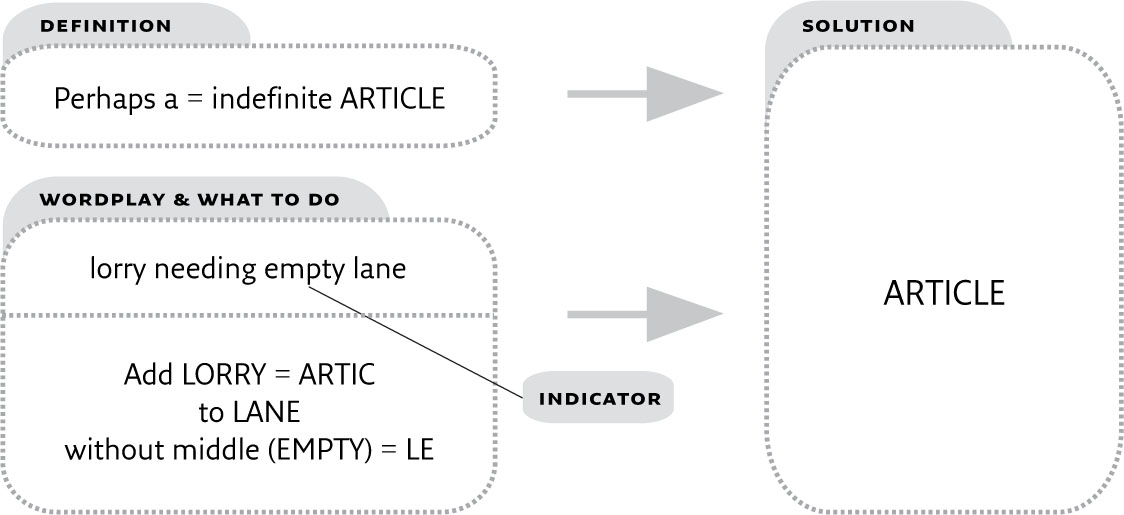

Last, an instance, overleaf, of how separating the sentence into even its smallest parts is sometimes needed. This clue is a further demonstration of a letter selection indicator, empty for lane leaving the two letters le, and of a deceptive definition.

ADDITIVE CLUE: Perhaps a lorry needing empty lane (7)

6. Write bars in grid

Given word-lengths that indicate more than one complete word (e.g. 3-7, or 3,7), some solvers automatically write the word divisions as bar-lines into the grid and find that helps. The bars can be either vertical or horizontal depending on whether they are split words or hyphenated words. This little trick can be especially useful when the word to be found is in two parts and the first letter, say, of the second of the parts is given by an intersecting solution.

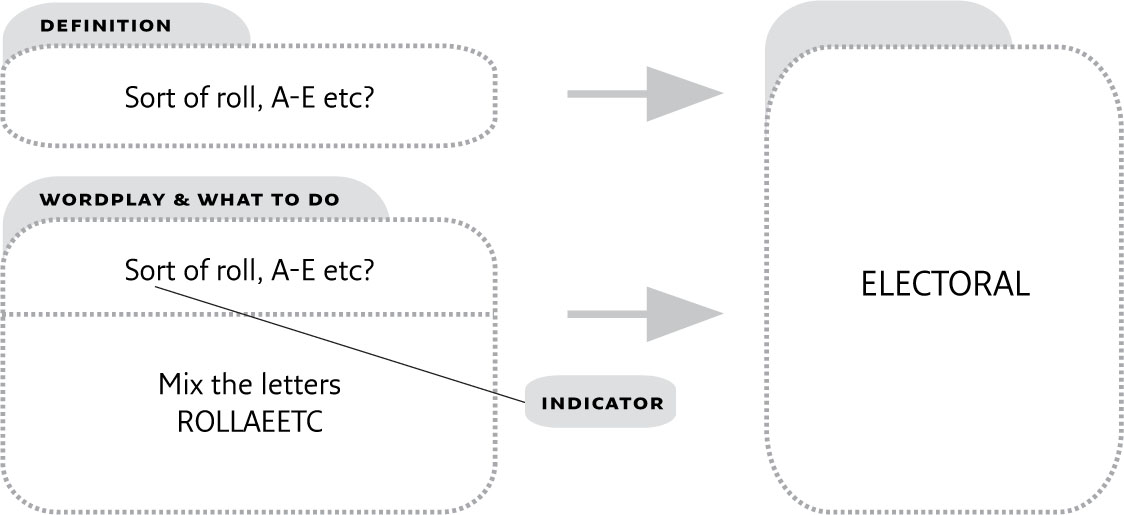

7. Ignore punctuation

In a nutshell, only exclamation marks and question marks at the end of a clue are meaningful; other punctuation should usually be ignored. For example, the anagram fodder can include letters or words with a comma or other punctuation in between, as in this tricky clue:

ALL-IN-ONE ANAGRAM CLUE: Sort of roll, A–E etc? (9)

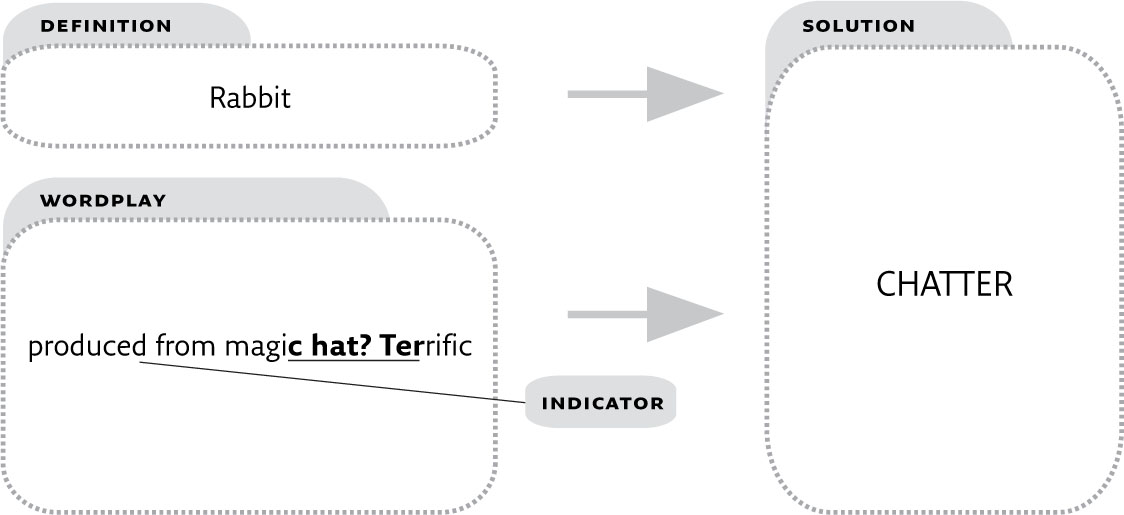

Another example of this is seen in the clue that follows:

HIDDEN CLUE: Rabbit produced from magic hat? Terrific (7)

The question mark and capital T are both to be ignored. There is more on misleading punctuation in Chapter 9, here.

8. Guess

An inspired guess can work wonders; you just feel that you know the answer without recognizing why. I have watched this intuitive process in my workshops and it’s magical. On one occasion a lady in her late 80s, a solver evidently for almost as long, was often able to come up with the answers before anyone else but had no idea how she had done so. Unfortunately, this method doesn’t work for everybody.

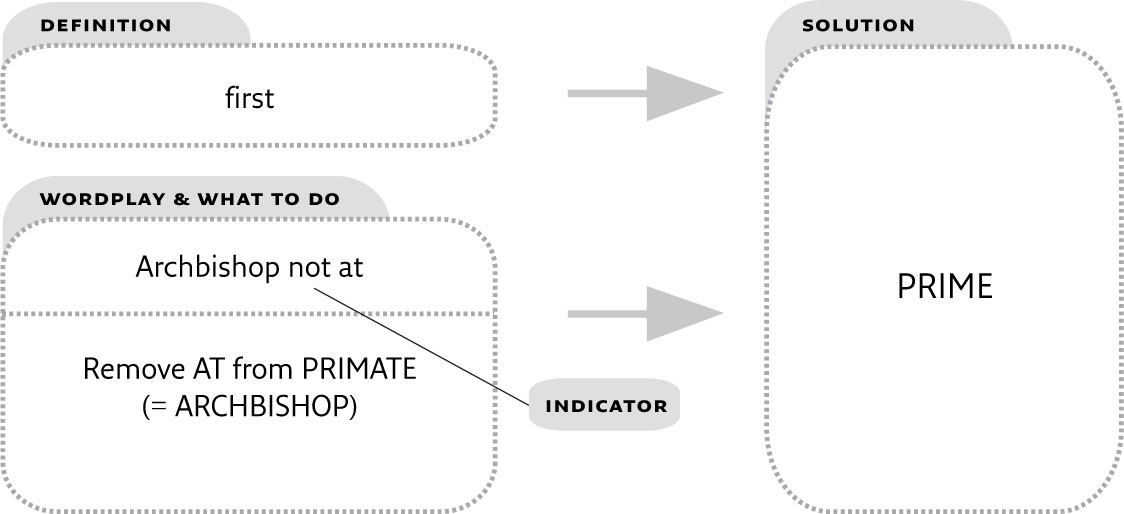

9. Think comma

One of the most useful tips I received as a novice was to imagine a comma in any part of the clue sentence. As we have seen in nearly all the examples so far, clues consist frequently of a string of words, each one of which has a part to play, and separating them into their meaningful parts can prove very helpful. In the next clue, imagining a pause between the last two words makes the solution much easier.

TAKEAWAY CLUE: Archbishop? Not at first (5)

10. Try to memorise frequently-occurring small words

The same three- and four-letter words inevitably crop up a lot and successful solvers store up words like pig, sow, cow, tup and hog for farm animal (or even just animal) and smartly bring these into their deliberations. I realise that many of my readers will have better things to remember, so let’s move on.

11. Advice on cracking anagrams

After you have identified an anagram indicator, counted the number of letters in the anagram fodder, including any abbreviations, and seen that they make up the given word-length, what techniques are there to find the solution?

People have their own familiar way of sorting out anagrams. Some find using Scrabble tiles works well; often the simplest method involves finding the right combination from careful scrutiny of the letters, looking for the commonly occurring -ing, -tion, -er, -or endings.

If this does not work, the anagram fodder can then be written down in various ways: in a straight line, in a diamond shape, in a circle, in reverse order or in random order. With longer anagrams, this can involve several rewrites in different orders until the answer emerges. In cases where the definition is something not very specific, such as plant or animal, it may be best to defer resolution until some intersecting letters have been entered.

Finally there are electronic aids as listed in Chapter 12 which can take all the pain (but maybe some of the enjoyment) out of the process.