Leaders err when they use cost cutting to reach financial targets. Long-term success requires that leaders focus on increasing the value that their organizations deliver to customers. Managing exclusively by financial results is ineffective in creating real value, since it leads only to transient benefits. Financial numbers are by definition lagging indicators, so by the time leadership takes action, it’s already too late. The damage to the organization’s reputation and customer satisfaction has already been done. By contrast, fit companies manage by means. They monitor, fix, and improve their operational processes in real time. Figuring out how to increase the value created by any process yields both happier customers and, inevitably, lower costs.

Don’t go on a diet. Don’t try to lose weight. And if you’re a business, don’t try to cut costs.

Do improve your time to market. Do lower your defect rate. Do build the flexibility to serve different customers in different ways. Do strive for zero accidents.

Real fitness isn’t defined by overall weight or by body fat percentage. Sure, if you’re 5′6″ and weigh as much as a double-door Sub-Zero refrigerator, you should probably put down the box of Twinkies. But if you’re a 5′10″ fashion runway model tipping the scales at 102 pounds soaking wet, you’re probably not very fit either. Skinny, yes. Employable in Paris and Milan, definitely. But not especially fit. Real fitness isn’t just about body mass index. It includes cardiovascular capacity, muscular strength, and flexibility. And if you’re an athlete—even a recreational one—you also need coordination, agility, speed, and quickness. You can’t gain those capabilities just by dieting.

To be sure, improving fitness requires healthy eating (and maybe even a little dieting). Mo Farah, the British distance runner who won gold medals in the 5,000-meter and 10,000-meter races in both the 2012 Olympics and the 2013 World Championships, eats pasta, steamed vegetables, and grilled chicken. For both lunch and dinner. Every day. (Although he did celebrate his Olympic triumph by allowing himself a single hamburger after the final race. Consider it the four-year burger.) But true fitness goes far beyond that. It requires exercises to build strength and flexibility, speed and stamina, aerobic capacity, and injury resistance. Weight loss—or in the case of these elite athletes, weight maintenance—comes as a result of their exercise and their fitness regimens. Weight loss is an ancillary benefit, not the goal of their efforts.

There’s an organizational parallel here: a company can’t get fit simply by cutting costs. To be sure, it can improve its income statement in the short term by laying off workers, closing offices, banning color copies, and getting rid of the coffee machine. That’s not going to make the organization fit, however, because organizational fitness isn’t just about low expenses. It includes the ability to react quickly to market shifts, to create and deliver new products and services, and to continually improve process efficiency and effectiveness—all in the service of delivering greater value to customers. Cutting expenses as a way to organizational fitness is like cutting calories as a way to personal fitness. At its logical extreme, it results in corporate anorexia nervosa—a feeble organization filled with dispirited employees unable to compete in the marketplace and serve customers. Sunbeam Corporation is the poster child for this misguided approach. Sunbeam hired “Chainsaw Al” Dunlap in 1996 to turn the company around. Within a year, he had laid off half the company’s staff (6,000 people) and eliminated 90 percent of the company’s products. Some said that he had gone too far, cutting muscle and not just fat.1 They were right: by 2001, the company was bankrupt.

There’s another parallel between dieting and simple expense cutting: neither works in the long term. It’s common knowledge that the vast majority of people who lose weight on a diet regain it within a year or so. That may be partly due to a lack of discipline or a failure of willpower. But there’s more to it than that. When obese people embark on a weight-loss program, the body actually fights to regain the weight it has lost. It acts as though it’s in danger of starvation (even if the person is still overweight) and pulls out all the metabolic stops to encourage more food consumption. It produces more ghrelin, a gastric hormone that stimulates hunger, and generates less peptide YY and leptin, hormones that suppress hunger.2

Organizations that simply cut expenses tend not to maintain their new weight either—they also fight to regain the weight that’s been shed. More often than not, there’s no concomitant reduction in work—it simply gets shifted around after layoffs. Employees take on the additional responsibilities of a colleague or a boss. They work longer and harder, but because the underlying processes aren’t functioning any better, and because these companies haven’t focused on improving how they operate, work doesn’t get done faster, better, or more easily. Eventually, after the financial crisis passes, the organization brings back the coffee machine, permits color copies, and caters meetings again. Travel restrictions are lifted. Gradually, the company hires people to refill the roles that were eliminated earlier. The weight comes back on, and the organization is just a market downturn away from another round of layoffs and cost cutting. McKinsey & Company detailed this situation in late 2009, as the economic recovery following the Great Recession began to pick up steam:

An international energy company that needed to save money fast started by simply defining the amount of savings it needed and then required each department to cut costs by a similar amount, primarily through head count reductions, which varied from 17 to 22 percent. The reality, however, was that the company needed to invest more in certain technological areas that were changing quickly, as well as in operations, where performance was far below industry benchmarks. What’s more, the HR and IT departments substantially duplicated certain activities because different layers in the organization were doing similar things. Much deeper cuts could therefore be made in these functions, with little strategic risk. But the company cut costs across the board, and just six months later, technology and operations were lobbying hard to bring in new staff to take on an “uncontrollable workload,” while substantial duplication remained in HR and IT.3

The truth is that most companies treat expense reduction as a one-time exercise. When the pressure is off, expenses come back, because the company hasn’t invested in building internal capabilities and improving processes. Nearly half of the executives in a recent survey by the consultancy Strategy& acknowledged that their companies cut costs due to external events or outside pressure, not due to a culture of continuous improvement.4 In fact, some research shows that only 10 percent of cost reduction programs show sustained results three years later.5 Like a person whose health efforts concentrate on weight loss through fad diets, the fat comes back. Always.

The alternative is for organizations to focus on building fitness, not on reducing costs. In this context, fitness means becoming faster, more agile, and better able to take advantage of new opportunities and serve customers better. It means examining the processes by which the organization operates. It means focusing on the means by which work is done, not the (financial) ends. A corporate “fitness program” develops employees’ capacity to solve problems and improve performance, with the long-term goal of increasing the value provided to customers. And with greater customer value comes improved financial performance. In fact, cost reduction is an inevitable outcome of the pursuit of fitness—but cost reduction is not the primary objective. If it were, the organization could simply lay off workers and beat up suppliers for better prices, which, as we’ve seen, yields only short-term benefits.

There’s another problem when organizations focus on cost reduction: it’s a demoralizing, zero-sum exercise. It’s dispiriting for everyone involved with the organization, generating fear and anxiety for all people involved. By contrast, increasing fitness is energizing and exciting, because there are so many ways to do it, and there’s always more that can be done. Author Mark Graban tells this story about a workshop he led at a hospital:

The nurse manager told me, “I thought we were supposed to come up with ideas for reducing costs. I couldn’t think of any. But, when you explained that kaizen [continuous improvement] was about saving time, making our work easier, and improving patient care, I realized I had a lot of ideas after all!”

In my experience, healthcare professionals generally don’t get excited about the department’s budget or the hospital’s bottom line. They just don’t think about those things very much. They’re thinking about their patients, and they’re annoyed by problems and waste that get in the way of providing the best care to them.6

Sometimes it’s easy to increase fitness by improving the process. In the case of QBP above, direct observation of how the work is being done revealed the problem quickly. But the issues aren’t always as clear as the lack of tape guns and box cutters. To make more subtle problems visible, you need to create metrics and targets that tell you how the process is running. Many of the metrics will relate to the customer (either the ultimate customer, or just the next step in the process). Some of them—like quality—won’t tie directly to the customer but obviously affect the ultimate performance of the system.

For example, in 2006, at Franciscan St. Francis Health in Indianapolis, the emergency room (ER) was performing so poorly that it ranked in the 13th percentile in patient satisfaction, meaning 87 percent of hospitals were performing better than it in patient satisfaction. Although it was recently named a top 100 hospital in the country for overall quality by Healthgrades (which put it in the top 2 percent of all hospitals for quality patient care), it wasn’t satisfying its customers’ expectation for fast service. Joe Swartz, the director of continuous improvement, led a team to improve this number by focusing on two of the key drivers of satisfaction: the time it took from arrival at the ER till the patient saw the doctor (door to provider), and the time from arrival to departure (door to discharge). Although it sounds simple, this wasn’t an easy shift to make: the nurses and physicians weren’t accustomed to it, and they worried that it would encourage shortcutting of the process and lead to a reduction in the quality of patient care.

Swartz allayed those fears by explaining that irrespective of any changes they made, the quality of care was nonnegotiable—they had to provide either the same or a higher level of care. However, the process could be simplified to reduce the delays, motion, travel, and frustrations that got in the way of providing that care. Then he showed them the data: in 2006, the average door-to-provider time was 45 minutes, which was the biggest factor in the low patient satisfaction scores. By engaging staff to solve the problems that made their jobs so difficult, they were able to make dramatic improvement. Table 2.1 shows some of the recent data:

TABLE 2.1 Franciscan St. Francis Health drivers of patient satisfaction

This improvement didn’t occur overnight. It took seven years of progressively more aggressive projects. The breakthrough was the realization that all the ER rooms filled up by midday, forcing new patients to wait for a long time before rooms opened up. (Of course, this wasn’t apparent until the team focused on the impediments to providing care quickly.) Swartz’s team decided it could increase the velocity at which patients moved through the rooms by radically redesigning the process. The new process moved lower-acuity patients from room to room (each room with a unique purpose) as they progressed through their stay, rather than occupying a single room for the duration. This change freed up individual ER rooms for new patients, creating additional room capacity.

This change increased patient satisfaction in several ways. First, it enabled patients who were in pain to be diagnosed and receive pain medication faster. Second, shorter door-to-provider time reduced patient anxieties. Third, moving patients from an Intake Room to a Procedure Room to the Lounge and finally to a Discharge area made them feel that they were waiting less.

Franciscan St. Francis Health has improved processes in other areas throughout the hospital as well. Over the past eight years, employees have identified and implemented over 23,000 improvements, saving millions of dollars. Of course, the hospital does track the results (patient satisfaction and percentage of patients leaving without treatment), but the critical measurement it watches now is the length of time patients are waiting. That’s customer (patient) value.

It’s worth noting that as an administrator, Swartz was deeply influenced by his earlier experience as a competitive wrestler. He was a state champion, won the Mideast Regional Olympic Wrestling Trials, placed ninth in the Olympic trials, and trained with the Olympic team in Colorado Springs. While training with the team, he noticed that the best wrestlers didn’t focus very much on fancy wrestling moves. Rather, they spent most of their time practicing the basic techniques over and over again. This was revelatory. He saw that the key to excellence in both athletics and in business was to become extraordinarily good at the fundamentals—like getting patients through the ER faster.

In a similar fashion, Black Diamond Equipment, a maker of outdoor apparel and equipment, was struggling to meet customer demand for some of its product. The VP of manufacturing, Wim de Jager, realized that downtime of critical machines at the factory was a major factor affecting the company’s ability to ship on time—but he couldn’t see the downtime easily. He installed red lights that indicated when machines were down, and then he connected the whole system to a clock so he and his production team could measure the total downtime each week. This measurement made clear just how much time was being lost and galvanized the company’s resolve to deal with the problem. Within three months the team was able to reduce downtime from 45 percent to 20 percent—allowing the company to meet customer demand and ship product on time.

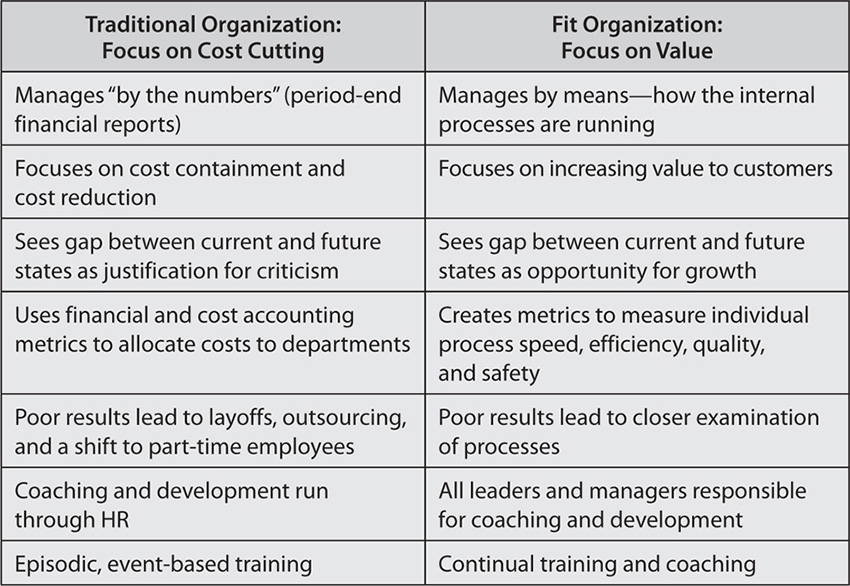

Notice that neither of these organizations used poor results as an excuse to cut costs. Instead, they focused on fitness: managing by means to increase their ability to provide customer value by improving their processes—and that, inevitably, led to better results (see Table 2.2).

TABLE 2.2 Focus on value rather than cost-cutting

I wasn’t there, but I’m pretty confident that when Mo Farah (Olympic gold in the 5,000 and 10,000 meters, London 2012) began thinking about competing in the Olympics, he and his coach talked about more than just the need to run a specific time in each race. I also wasn’t there when Roger Federer began his assault on the tennis record books, nor when Tiger Woods began his epic run of PGA majors wins, but I’m pretty sure that their plans were far more detailed than hitting more winners or shooting a lower score. All of these athletes set an ultimate goal (winning gold, winning Wimbledon, winning the Masters) and then worked with their coaches to build the specific skills necessary so that they could be in a position to win. Mo Farah needed to develop a final 400-meter kick to outrun the Kenyans and Ethiopians. Federer needed to be better at the net. Tiger needed to develop a short game. All great athletes break down their strengths and weaknesses and work to enhance the former and eliminate the latter. They focus on the means to the end, not simply the end itself.

Fit organizations take the same approach. They don’t simply hold a two-day retreat where the executives set lofty goals without input from the managers and frontline employees who actually do the work. Instead, fit companies incorporate the front line into the planning exercise itself so as to connect the overarching goals with the necessary process-level improvements. After all, it’s one thing to say that you want to improve patient satisfaction scores (the ultimate goal); it’s quite another to work with your staff to figure out how to discharge patients more quickly (the means to the end).

As you consider where you want to take your organization, it’s essential that you examine your key processes with your team to understand where the weaknesses are. What process obstacles block the way to delivering greater value? Or if there are no obstacles today, what processes will enable you to reach a higher level of performance and deliver greater value to the customer? How will you reduce the waiting time in the emergency department? How will you design and develop new products more quickly? How will you increase the number of outbound customer calls to proactively serve your retail customers rather than wait for them to call you? Table 2.3 provides some ideas of what these process-oriented metrics might look like.

TABLE 2.3 Process-oriented metrics

Of course, you’ll want to work with your team to determine the relevant key performance indicators (KPIs) for your organization. These KPIs will focus your activities and efforts on the improvements that will enable you to attain your overarching goals.

With rapidly rising medical costs and lower reimbursements, hospitals in the United States are under enormous financial pressure. For the most part, they’ve dealt with this issue through traditional cost-reduction strategies: negotiating lower prices and more advantageous contracts with vendors, standardizing product choices, laying off staff, reducing contributions to retirement plans, and cutting or freezing salaries. Even if you don’t closely follow the financial performance of companies in the healthcare industry, you probably know that this approach hasn’t solved anything.

A major children’s medical center in the United States faces the same financial challenges as any other hospital, but it has taken a different approach. Although cost containment is still important, it’s no longer leadership’s sole method of dealing with financial pressures. Instead, the hospital is building organizational capacity to increase the value it can provide to patients. The radiology department is a terrific example of how this shift in focus has paid off both for the hospital and for its patients.

This children’s hospital is far and away the premier pediatric hospital in its community: if your kid is sick, you’re taking him or her there. But in 2007, the hospital was losing patients needing MRIs to other facilities. Parents were going elsewhere because they had to wait 16 weeks for an MRI appointment. (It’s actually more accurate to say “about 16 weeks”—according to one of the senior staff directors, when the hospital started analyzing its workflow and patient throughput, the directors realized they didn’t even know what the actual wait times were.) Most people in the section thought that the wait was “only” 8 to 12 weeks, but that was only because the radiology department didn’t have a robust system for tracking the requests that came in on scraps of paper, in faxes, or via phone calls. You can imagine that no matter how good the care was at this hospital, parents weren’t going to wait four months to get an MRI. In fact, the situation had deteriorated to the point that the hospital’s medical director demanded that one day per week on the schedule be reserved just for inpatient MRIs so that the other services in the hospital could take care of their patients. While understandable, that just made the wait times worse for outpatient scans.

As I mentioned earlier, organizational fitness means becoming faster and more agile, with the goal of serving customers better. Realizing that the situation was untenable, and seeing that no cost-cutting program in the world would improve the situation, the radiology department set about reducing wait times. The staff members learned how to map patient flows and solve problems through root cause analyses. They identified bottlenecks in the system and created standardized templates to make the scheduling process consistent. Recognizing the power of making work visible, they developed a system to make incoming MRI requests visible to everyone. With no increase in the number of machines or staff, the hospital reduced wait times to two weeks or less and was even able to schedule next-day appointments for urgent cases. The focus on increasing the value provided to patients—faster access to MRI appointments—resulted in happier patients, less stressed employees, and smoother flow for the hospital’s other departments. Better utilization of the machines also generated an additional $5 million in revenue for the department per year.

Like most healthcare organizations, this hospital still has plenty of problems that it needs to solve. An additional $5 million isn’t a panacea for all of them. But it does mean that the hospital doesn’t have to lay off people or cut salaries in the department. In fact, the radiology department’s success shows that it’s possible to provide better service and increase revenue without spending money. Even more important, though, is the increase in organizational fitness—solving the patient flow problem increased employees’ capacity to improve processes and solve other problems.

If you’re an outdoor enthusiast, you know how exciting it is when you find a piece of clothing that fits your needs perfectly: it fits just right, it looks just right, and it has all the technical features that you need and want. Maybe you live in a rainy environment, and you want a waterproof jacket with a hood for hiking. Or perhaps you want a lighter, thinner, and softer fabric on the outside for your bike rides. Or maybe you just want something in orange. Unfortunately, it’s not always so easy to find that perfect piece of apparel because your clothing options are, to a large extent, determined by decisions made 18 months earlier by a bunch of designers and developers you’ll never meet, and who may very well not engage in the activities you love. Moreover, even if a company did make the perfect jacket for you, you might not see it unless you were lucky enough that your local retailer liked waterproof, hooded orange jackets with a zippered chest-pocket on the right side enough to bring them in and put them on the shelves.

Wild Things Gear makes technical apparel that consumers can customize for their own needs. CEO Ed Schmults believes that customization is especially important for technical clothing because it allows customers to create the functionality that’s important to them, whether that’s for ice climbing, skiing, or just tramping through the woods with the dog. Of course, customization is nice for fashion reasons as well. As Schmults says, “Who am I to tell a customer his jacket is ugly?”

Product customization is impossible if you manufacture in Asia (like virtually all outdoor companies). Asian factories are built for mass production: long production runs of hundreds or thousands of garments with minimal variation. It’s also tough to get products to consumers quickly if they’re produced halfway around the world—ocean shipping, customs clearance, and logistics (ocean port to warehouse to consumer) add three to four weeks of transit time. Airfreight is much faster, of course, but it’s cost prohibitive for the company since most consumers aren’t willing to pay for that service.

Schmults realized that to deliver the increased value that comes with a customized product, he’d have to develop the ability to make clothing in the United States. He’d have to get faster, more productive, and more skilled in apparel manufacturing—a tough job, given that the domestic apparel industry has been eviscerated over the past 20 years as companies have closed their factories and outsourced their work to Asia. However, using lean manufacturing techniques such as cellular production, one-piece flow, kitting of components, etc.—along with extensive training—Schmults was successful in making technical outdoor gear in the United States. Now, with a website that allows customers to configure their products online, domestic production, and the elimination of retailers for distribution, consumers can go from designing their own jacket to delivery at their house in only 14 days.

So, more value to the consumer—but what about the company? Moving away from traditional overseas mass production has meant faster production, less finished-goods inventory, and lower working capital requirements. Quality is higher and overall costs are lower. Indeed, even as sales are growing steadily, the company’s return rate is only 6.8 percent, whereas most fashion brands have return rates as high as 40 percent—and that difference goes right to the company’s bottom line.

Many smaller companies that can’t afford to set up offices internationally sell their products through distributors. The distributor buys the inventory from the company and then uses its people to sell the products (along with other products in the same or related categories) to retailers in that country. This arrangement allows small companies to generate revenue from around the world, even if they can’t afford the expense of setting up offices and hiring staff internationally. For a company with this kind of relationship, the distributor becomes one of its most important customers.

Ruffwear, an Oregon-based company, designs and builds gear that allows dogs to join their owners on outdoor excursions—including packs for them to carry their own food, boots to protect their feet from sharp rocks, and even life jackets (!) to keep them safe on canoe or kayak trips. Like most outdoor industry companies, Ruffwear generally builds and sells products in two seasonal batches. (This makes sense—although dogs are happy to go outside any time of year, most dog owners confine their outdoor adventures to the summer and fall.) The company uses independent sales reps in the United States, but it sells in Europe through a distributor.

The twice-yearly batches of product posed a financial difficulty for the company’s distributor. To keep shipping costs to a minimum, it would buy a full container of new product from Vietnam so that it could have inventory to sell at once, and additional inventory to replenish retailers’ shelves during the course of the season. Financially, the inventory was like the proverbial pig in a python: a giant bulge of products that consumed an enormous amount of the distributor’s cash, making it difficult to pay Ruffwear for the goods in a timely fashion, to say nothing of having money to spend on marketing and promotions.

The huge batch of inventory created another problem as well: with so much inventory in stock, the distributor would have to close out the old products at a discount to make room for the next season’s products. This meant that Ruffwear’s new products had to compete with its old, discounted products for space on the retailers’ shelves. Alternatively, in order to get its new products into the market, Ruffwear had to buy back its old inventory from the distributor.

This dynamic is actually quite common in many industries, not just with industries that operate on a seasonal basis. Manufacturing and then holding too much product leads to endless discounts and sales, which hurt profitability for the manufacturer, the distributor, and the retailer alike. As Will Blount, the president of Ruffwear explains, “We have to realize that the biggest waste we create is manufacturing products that can’t be sold for a healthy margin.”

Blount, along with Young Joen, his director of supply chain, saw that this relationship with the distributor wasn’t a recipe for growth in Europe. But rather than cutting costs at the head office, or negotiating harshly with his suppliers for better pricing, or pushing the distributor to bolster its financial reserves, the company decided to get fit—get faster and more agile in the way it worked with the distributor. First, it created greater visibility in its supply chain by investing in a centralized information system that provides the company with daily updates of actual sales and inventory levels. Next, it changed the way it shipped its products to Europe. In the past, it sent its products from Vietnam in standard cartons via ocean freight. This practice required the distributor to commit to which products it wanted four months in advance. Ruffwear switched to sending products from the United States in gaylord boxes via airfreight. This allowed the company to pack a mixed product assortment into a single box (which was much cheaper, given the company’s soft and odd-sized products), and to deliver it significantly faster—five days in transit, instead of four weeks. Finally, Ruffwear ended the practice of delivering an entire season’s worth of products in one shipment. Instead, it sent much smaller batches of product as often as twice per week.

The benefits from these changes were enormous. The distributor’s cash flow improved because its money wasn’t tied up in a huge batch of inventory. It was able to order products more accurately because it didn’t have to forecast four months in advance. Smaller shipments also lowered logistics costs: the distributor uses a third-party warehouse that charges by the cubic meter. With less inventory on hand, storage costs were lower.

Naturally, the benefits accrued to Ruffwear as well. Accounts receivable declined by 62 percent. Closeouts went from 5.8 percent of total unit sales per year to 1.4 percent, meaning that the company didn’t have to compete with its own discounted products when introducing new items. Taken together, these changes enabled the company to lower retail prices for its products in Europe by 7 percent—and still increase profits.

Blount sums up the benefits of organizational fitness elegantly:

We want to build a reactive system that can take advantage of market conditions. Although we have a higher salary-to-revenue ratio than most other outdoor companies, the ratios of our other expenses to revenue are lower than those other firms. We take the savings from operation efficiency and invest in people.

These three examples demonstrate that a focus on increasing value for customers can yield even greater benefits than merely focusing on cost reduction. Cost cutting leads only to short-term benefits, with no long-term gain in skills or capability. By contrast, a value focus forces an organization to examine and improve its processes—making them faster, easier, safer, and higher quality. A cost-cutting focus puts the emphasis on financial results. A value focus puts the emphasis on process, which increases customer satisfaction and delivers long-term, sustainable benefits to the organization.

Here are some considerations to shift from cost cutting to value-adding efforts.

What cost-reduction initiatives do you have underway now? Why did you target these areas?

What cost-reduction initiatives do you have underway now? Why did you target these areas?

Talk to your marketing, sales, and customer service teams. What customer needs are not currently being met? Is your organization falling short in terms of quality, availability, or support? List these opportunities. These are the gaps that you need to close.

Talk to your marketing, sales, and customer service teams. What customer needs are not currently being met? Is your organization falling short in terms of quality, availability, or support? List these opportunities. These are the gaps that you need to close.

Bring your frontline and middle management workers together to figure out how to close these gaps to produce the end results you’re looking for. (Remember: it’s leadership’s job to identify these gaps and decide which ones to address. It’s the role of middle management and frontline workers to figure out how to do it.) Use coaching, visual management, and standard work to help workers reach these new targets.

Bring your frontline and middle management workers together to figure out how to close these gaps to produce the end results you’re looking for. (Remember: it’s leadership’s job to identify these gaps and decide which ones to address. It’s the role of middle management and frontline workers to figure out how to do it.) Use coaching, visual management, and standard work to help workers reach these new targets.

What key performance indicators can you create to enable you to track the improvements your team is making? These KPIs should be focused on how your processes operate rather than on your month-end financial results. Some examples:

What key performance indicators can you create to enable you to track the improvements your team is making? These KPIs should be focused on how your processes operate rather than on your month-end financial results. Some examples:

Process productivity (labor hours per unit)

Process productivity (labor hours per unit)

Number of items in a backlog queue

Number of items in a backlog queue

Percentage of forms filled out completely and accurately

Percentage of forms filled out completely and accurately

Length of time to respond to customer inquiries

Length of time to respond to customer inquiries

Number of incoming customer help desk calls (by product or service)

Number of incoming customer help desk calls (by product or service)

Customer satisfaction ratings

Customer satisfaction ratings