Organizations are typically divided into functional silos: finance, marketing, sales, operations, and so on. There’s nothing inherently wrong with this structure, but it increases the risk that the people and the departments within the company will focus on improving their own, internally directed metrics at the expense of the customer. It would be like a baseball player focusing on his home run tally at the expense of his team’s ultimate World Series victory, or like a marathon runner focusing on how much he can bench press and not how fast he can cover the distance. This internal orientation is the natural default of all organizations, a combination of human desire for immediate rewards and evidence of success as well as natural organizational metabolism. Fit organizations, on the other hand, keep the customer in mind at all times—everything is viewed through the lens of the customer’s perspective. That can be accomplished by a total reorganization of the way the company is organized, or it can be done by appointing a person to watch over the entire process by which the company creates value. Regardless of how you approach it, it’s a shift that is essential to creating a fit organization.

Most organizations, and the people in them, spend an obscene amount of their time, energy, and resources working and fighting for the wrong things. They succumb to the natural default of organizational life where salespeople do what it takes to win bonuses, supply chain experts beat up vendors for pennies, workers behave to avoid punishment, and departments hunker down into their safe silos, walled off from the customer by their internally facing performance measurements. It’s often a wonder that anyone shows initiative or spontaneity in delivering value for the customer.

Think about how you start a fitness program. Before beginning, you have (or should have) a goal. Are you trying to run a marathon, or are you trying to improve your tennis game? Do you want to build muscle or cardiovascular endurance? Are you trying to prevent a chronic knee injury from coming back, or do you just want to look better in a bathing suit this summer? These questions are critical to determining what specific exercises, and what kind of fitness routine, you’ll pursue.

Different goals necessitate different training regimens. Running the Boston Marathon requires stamina and lower body muscular endurance, whereas doing a 5K race places a greater premium on speed and cardiovascular capacity. And of course, any sort of running event requires a completely different kind of fitness than a tennis match, which demands agility, flexibility, quickness, and a fair amount of upper body strength.

Now, most people intuitively understand the need to orient their workouts toward their specific athletic or fitness goal. You don’t see too many people doing a set of 400-meter sprints on the track to improve their golf game, or doing a bunch of bicep curls with heavy weights to prepare for a marathon. Why? Because your mile time doesn’t correlate well with your ability to get out of a sand trap, and your bicep girth isn’t going to help you at Heartbreak Hill in the Boston Marathon.

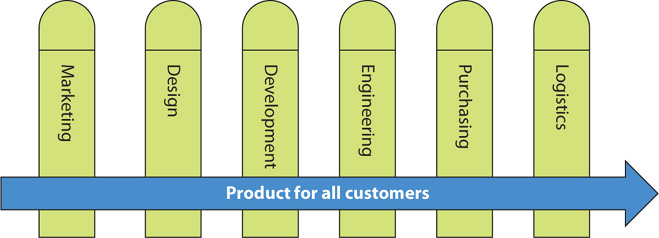

However, we don’t carry that mindset over to the business world. Irrespective of the industry we’re in, the type of products or services we provide, or the kind of customers we serve, our businesses are organized into pretty much the same kind of functional silos—sales, marketing, finance, product development, customer service, HR, IT, and so on. For example, Figure 3.1 shows what silos might look like in product development:

FIGURE 3.1 Silos in product development.

Of course, there’s nothing inherently wrong with an organization built around functional silos. But that structure has a real and significant consequence, because the siloed organizational chart profoundly shapes our thinking. It pulls workers’ focus away from the customer’s needs (either customers in another department, or the ultimate consumer) and shifts it internally toward the department’s needs. The silo mentality causes people to think more about what’s best for their department than about what’s best for their customer. Put another way, it makes people think “vertically” instead of “horizontally.”

This shift in thinking leads ineluctably to suboptimization of organizational processes. Departments within a company concentrate on improving metrics related to their specific domain, rather than on improving the customer experience. For example, in most companies, customer service departments are evaluated on how fast reps are able to end phone calls. Shorter phone calls means that the company needs fewer people to answer the phones—which means lower costs in the department. Some companies also argue that shorter calls mean happier customers because questions are being answered more expeditiously (although most of us would argue that this is pretty shaky ground to stand on). In fact, there’s a host of software applications that slice and dice call center data to help managers figure out how to “improve”—that is, reduce—the amount of time spent on the phone. In many other companies, customer service is outsourced to India or some other low-wage country in order to reduce department costs, even if that results in lower levels of service. It’s a rare person who hasn’t had a painful experience with a rep whose English is difficult to understand, who reads off a script that bears little relevance to the customer’s situation or mood, and who seems more interested in getting the customer off the phone quickly rather than in resolving his or her problem.

What’s missing from this vertical, silo-focused analysis, of course, is customer satisfaction. Reducing the average time per call or overall department expenses may be good for department metrics, but it doesn’t necessarily improve the quality of the service that the customer receives. In contrast to this silo-focused thinking and measurement, online retailer Zappos doesn’t care at all how long reps spend on the phone with customers. Zappos is horizontally oriented, completely focused on the customer experience. The company’s first core value is “Deliver WOW through service”—and embracing that value gives the customer service team license to spend however much time and money that demands. (In 2012, the company set an internal record with a 10-hour, 29-minute phone call.) Or consider the legendary “empty chair” at Amazon. CEO Jeff Bezos includes an empty chair in important meetings with his senior leaders to remind everyone of the most important person to the company: the customer. The chair encourages attendees to think of their proposals and ideas through the customer’s eyes—what would she think? How would she react? Assessing your products, your services, and your work through the customer’s eyes: this is a pretty simple idea. And yet it typically gets lost in the daily activities of most organizations when they’re focused inward, toward the top of their functional silos.

Fujitsu Services, an IT service company, embraced this shift to customer orientation in a deep, systemic fashion. Facing stiff competition, customer dissatisfaction, and high levels of employee turnover, the company fundamentally restructured the way it provided service to its clients. Efficiency—an internal metric—was no longer the primary score. (The company continued to track call duration and total number of calls, but that was only to ensure correct staffing levels.) Instead, the focus shifted to “customer success” and satisfaction. Frontline call center staff were given responsibility for identifying product and process improvements that customers needed. They visited customer sites to better understand their working environment, and they developed customer-specific key performance indicators. They even provided advice to customers on how they could improve their own suboptimal processes. Fujitsu’s managers’ roles changed, too. Rather than using their authority to ensure worker compliance with internal policies and procedures, they took on a support role in which their primary responsibility was to provide frontline staff with the necessary knowledge and tools to handle the needs of the customer and assume responsibility for end-to-end service. These changes drove 20 percent higher customer satisfaction rates, improved employee satisfaction by 40 percent, reduced attrition from 42 percent to 8 percent, and lowered operating costs by 20 percent.1

Siloed thinking doesn’t just affect entry-level jobs like customer service. For example, hospital-based physicians are under continual pressure to increase patient throughput, which means spending less time with each patient. “Optimizing” the way that doctors spend their time in the exam room may increase hospital revenue and reduce the need to hire additional physicians (at least in the short term), but it doesn’t necessarily provide patients with the best care.

You would never use a single workout regimen for all your fitness goals; you would design it to meet a specific objective. Just like a fitness program needs to be oriented toward a specific goal—running a marathon, rehabbing a specific injury, playing better tennis—a fit organization orients around the customer and her needs. A fit organization thinks horizontally, not vertically.

Call centers are a particularly egregious example of how silo thinking hurts the customer experience. But siloed organizations also tend to struggle with internecine battles caused by poorly aligned incentives. For example, one of the core measures of performance in a credit department is the number of “days sales outstanding,” or DSOs. This metric shows how long it takes customers to pay their bills. The finance and accounting department doesn’t like it when DSOs increase, because the longer it takes to collect on open invoices, the more likely it is that the customer won’t pay at all. If the DSOs for a customer—or more important, a group of customers—get too high, the credit department will put the customer on credit hold and refuse to ship merchandise. From a strictly financial perspective, this makes sense. But certain types of customers have different sales rates—a major retailer like Foot Locker can move product more quickly and pay bills sooner than the neighborhood triathlon shop. Holding these two types of accounts to the same payment standards will inevitably result in slower sales (and a frustrated sales force).

Siloed metrics such as DSOs destroy intracompany teamwork as well. The financial executive is measured and rewarded in part on reducing DSOs, which leads her to tighten credit. By contrast, the sales executive is measured and rewarded on increased sales volume, which leads him to create dating programs that increase the DSOs. (Wiremold, a manufacturer of cable management equipment, solved this problem by tying incentive compensation for all high-level executives around the world to the same metrics—which were based on worldwide results.)

Vertical thinking also increases the likelihood of errors. Each time information passes from one silo to another, there’s a handoff—from sales to customer service, from product marketing to design, or from development to purchasing. Whenever you separate knowledge, responsibility, action, and feedback, you’re inviting disaster, because decisions are being made by people who don’t have enough knowledge to make them well.2 Not only that: despite the ubiquity of email and an overabundance of meetings, communication between and among teams of adults isn’t too far removed from the children’s game of telephone. Even with workers’ full focus and the best of intentions, messages get garbled when they’re passed from silo to silo. Most people reading this book have probably experienced a moment when they (or someone in their organization) said, “When did we agree to that?”

Vertical organization also slows companies down. Workers spend an enormous amount of time preparing PowerPoint presentations, writing memos, or simply sitting in meetings briefing people in the next department about what’s happening. Of course, none of this time and effort is value added from the customer’s perspective. It’s simply a necessary cost of doing business when work is flowing across departmental boundaries. Even worse, when work is handed off between functions, it almost always goes into some sort of queue, so the next person (or step) in the process has to wait until the preceding person does his job. The delays caused by these queues can be enormous.

Bison Gear & Engineering Corporation, a manufacturer of custom electric motors and gearmotors near Chicago, struggled with precisely this problem. Handoffs between designers, electrical engineers, and mechanical engineers led to a three-week lead time for new product development. In their market, three weeks just wasn’t good enough, and they were losing business to competitors. Bison responded by breaking down the silos between these departments in what they call a “project blitz.” The company puts a team of engineers together (literally—they move their desks right next to each other), protects them from interruptions by stretching police riot tape across the engineers’ area so that no one can enter, and has them focus exclusively on a single project until it’s completed. Work flows smoothly and continuously from one person to another with no waiting and no distractions. Also no memos, no presentations, and no meetings. The lead time to produce a custom motor now? Three days.

A fit organization focuses horizontally, toward the customer, resulting in higher quality, better service, faster response, and happier customers. Going back to the athletic metaphor, this is equivalent to planning a workout regimen with a specific event in mind, rather than focusing on individual muscle groups without consideration for the ultimate training goal. Horizontal orientation enables—even encourages—the company to optimize its activities for the benefit of the customer, and not the department manager or VP.

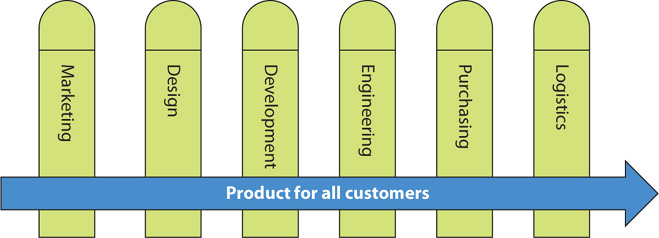

A company that thinks horizontally considers the types of customers it serves and breaks them down by their different needs (see Figure 3.2). For a consumer products company, that could mean domestic vs. international customers. For a law firm, it could be corporate vs. individual clients. For a hospital, it might be cancer patients vs. trauma victims. Each of these customer types has different product and service requirements, which can be best addressed by the creation of separate processes tailored to their needs.

FIGURE 3.2 Horizontal orientation by customer type.

Despite the advantages and intuitive logic of orienting around customer types, disbanding functional silos is a heavy lift for most organizations. More than a century of business tradition has led to the primacy of silos. This history, combined with the legacy of Frederick Taylor’s principles of scientific management (which argue for work specialization), makes it exceedingly difficult to orient in any other way. Additionally, most metrics and key performance indicators (KPIs) point vertically—time spent on a call in a customer service center; days sales outstanding in the credit department; commission percentage in sales; viewing only unit cost, rather than total cost, of a product in purchasing; and so on—which makes it all the more difficult to focus on the customer. Even when a company does have an internal advocate for the customer, all too often that person doesn’t have the formal authority or informal clout to change the decisions made by functional VPs.

Nevertheless, it’s possible to bring the benefits of horizontal orientation to an organization that maintains its functional departments.

In 1992, Asics, the athletic footwear company, was on a roll. Over the previous four years, the U.S. subsidiary of this Japanese firm nearly tripled revenue to $250 million, primarily by increasing volume in large chains like Foot Locker and Footaction. At the same time, however, sales through the specialty running channel suffered. Asics slipped from the top spot in this channel to number three. And although the sales volume from running specialty retailers accounted for only about 5 percent of the company’s business, these shops were critical to Asics’ brand image. For my first job out of business school, I was hired to fix this situation.

In talking with the specialty running accounts, I learned that they were leaving Asics for competitors like Saucony and Brooks because the company wasn’t serving their particular needs. Policies, processes, and systems that worked for chains with 1,000 storefronts that ordered 40,000 pairs of shoes at a time didn’t work for a single operator that ordered 72 pairs at a time. Figuring out how to work around the company’s functional silos to better serve these retailers was the challenge.

Big chain stores are sophisticated operations that manage their cash and inventory professionally. (Generally speaking. Lord knows that there are plenty of chains that struggle to do so.) Foot Locker, for example, places all its orders before the season starts, schedules delivery throughout the season to refill its stocks, and strategically holds extra inventory at its distribution centers as needed. It pays its bills on time, and when it has a problem, its sales clout gets it fast attention from a vendor’s customer service and leadership teams.

Small running shops are entirely different. They’re run on a tight budget—and that’s when the owner is sophisticated enough to even have a budget. In the 1980s and ’90s in particular, many of them were operated as a labor of love by serious runners who knew more about mile splits than about income statements. The owners were often disorganized and didn’t have a lot of cash to pay bills (when they could find them in the chaos of their desks), which landed the stores on credit hold with their vendors. Being cash poor also meant that they couldn’t buy a lot of inventory. As a result, they lived in fear of stocking out of a shoe in a customer’s size (if you lose a customer today, he’ll probably go to Foot Locker, and the sale will be gone forever), leading them to rely on vendors to carry enough inventory to “fill in” their stock with overnight shipments. By 1992, the Asics functionally oriented organization was terrific at meeting the needs of large chains, and terrible at meeting the needs of the small guys—and that’s why the running shops fled to Saucony and Brooks. Those smaller competitors had less business with the giant chains and could—or at least chose to—pay more attention to the running shops.

I realized that for Asics to address the different needs of the running specialty shop, virtually every department in the company had to reconsider the way they operated and the way they measured their performance. They needed to orient their services around these accounts.

Sales. Discounts are typically given to customers based on volume. Running specialty accounts can’t get those discounts because they can’t order enough products to meet the threshold. We created unique discount levels based on their smaller size (for example, 72 pairs of shoes, not 288 pairs). We developed specific sales programs and incentives for them if they would carry one additional SKU or increase an order of a particular model from 24 pairs to 36. Finally, to help them with their cash flow, we gave them special terms and dating: instead of Net 60 days, we went to Net 90 on “futures” orders and Net 60 on “fill-in” orders.

Credit. By any measure, most running specialty accounts are terrible credit risks compared to large chains or mass merchants. Nevertheless, we changed the threshold at which these accounts would be put on credit hold, and we allowed them to pay off their outstanding invoices more slowly than other accounts. The credit department even segregated these accounts when calculating overall Days Sales Outstanding (DSO) metrics.

Customer service. Because prompt customer service is essential to these accounts, and because they rely more on the customer service department, we formed a special team of customer service reps that handled only running specialty stores. When the customer service reps had free time, they would make outbound calls to the stores to check on inventory, place additional orders, and deal with any problems they had. Reps on this team weren’t evaluated on average call length.

Purchasing. Like most companies, Asics tended to have plenty of inventory of the shoes no one wanted and never enough inventory of the shoes that were in high demand. That made retailers reluctant to rely on Asics too heavily because the company often couldn’t provide fill-in orders. To allay their fears, we created a shoe bank each season that held extra stock of the “meat sizes” (8, 9, 10, and 11) of two core models. This bank was reserved for the exclusive use of the specialty running shops—no other class of retailer could poach from it.

Shipping. Specialty running shops hated competing with the big chains. The big guys would often discount shoes by five to ten dollars to get customers in the doors—a discount that the running shops, with their thinner margins, couldn’t match. To help them compete better, Asics began shipping one key running model to these stores a month before the big chains got it. That gave them one month of selling without major competition.

Promotions. Big chains have their own marketing budgets, or they extract marketing money from their vendors. Specialty running shops can’t match that. We increased the level of sponsorship for store-based running clubs with free and discounted products, as well as races that stores organized in their communities. We also provided low-cost running accessories (socks, T-shirts, etc.) to specialty retailers that increased their orders to certain thresholds.

Metrics. To emphasize the new horizontal focus on this specific customer, Asics abolished most of the internal departmental metrics related to them—and when they were maintained, like DSOs or inventory cost of the product in the shoe bank, they were calculated separately. We also added an overall satisfaction metric for the running specialty program as a whole and tracked sales through this distribution channel in aggregate, and the sales per storefront.

The results: Within one year, Asics recaptured the top position within this distribution channel, a position it held for the next 19 years.

Rich Sheridan started Menlo Innovations, a software development company in Ann Arbor, with the intent of bringing joy (yes, joy) back to software. He wanted to build a company that was a joyful place to work, with the intention that a joyful culture would create solid software that was a joy to use.

Sheridan’s long experience in the industry showed him that working in most software companies was like being in a salt mine, with executives flogging programmers through a coding death march to meet delivery deadlines; quality assurance staff trying to convince programmers that the bugs they find are real and need to be fixed—and after they fail, product managers trying to convince the sales team that those bugs are actually value-added features; and the documentation team laboring over manuals that no one will ever read. Okay—this description may be slightly hyperbolic. Not all software projects are that painful. But you can be sure that Healthcare.gov and Windows Vista (perhaps the largest software project failure in history, estimated at over $10B spent for a product that everyone hated and was killed as soon as possible) must have been pretty close to this level of dysfunction.

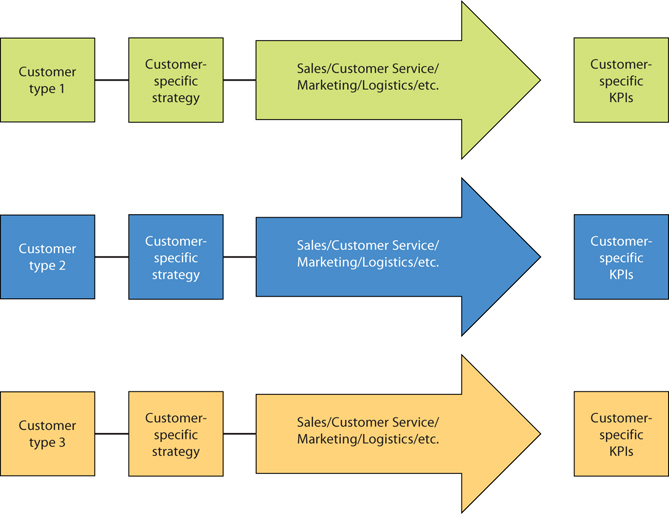

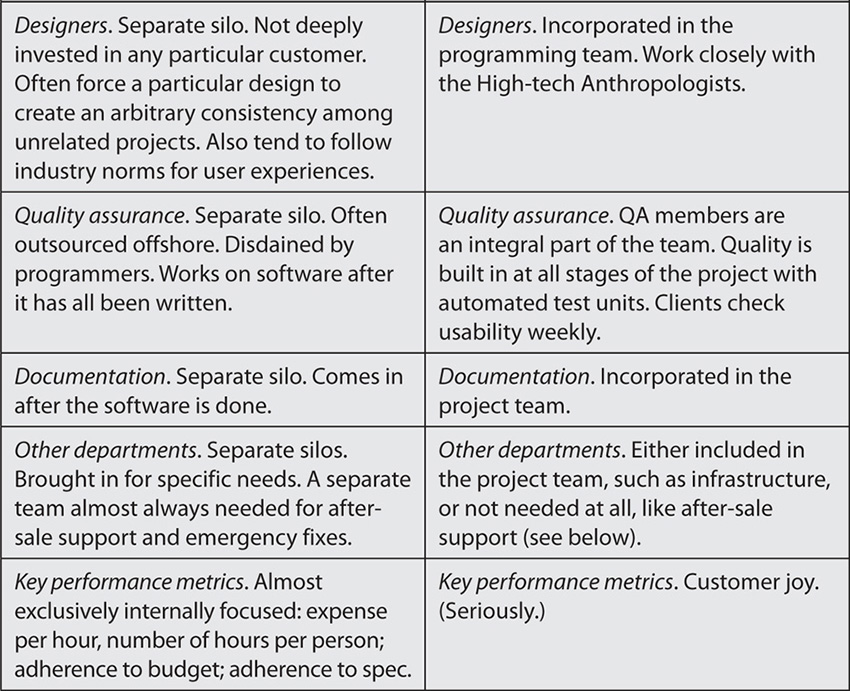

Sheridan realized that one of the primary causes of these problems was the traditional silo-based approach to software development. Here’s an overview of how a traditional software development company operates compared to the way Menlo does it:

Here’s a more detailed description of the differences in the way a typical software company works versus Menlo Innovations.

Programming. For cost reasons, many companies have outsourced their software development team to an offshore service provider in, say, Chennai, with management by the internal IT team in the United States. Needless to say, the language, culture, and time zone differences massively complicate the handoff of work within and between functional silos. There are even silos within the silo, as programmers are usually organized into towers of knowledge: database experts, low-level programmers, middleware experts, frameworks experts, application programming interface (API) architects and developers, and front-end developers. There’s typically a very strong technology bent to everyone on this team—in Sheridan’s words, “almost a religious fervor.” This is why you see programmers self-identify by a specific technology. For example, people will say, “I am a Ruby on Rails developer,” or “I’m a Microsoft.NET programmer,” or “I’m an Oracle 9.1.1.3 SP2 expert.” None of these people can do anything outside their tower of knowledge, meaning that projects are always at risk of delay if someone gets sick, goes on vacation, or leaves the company.

Business analysis/project management. This function is supposed to ensure that the project both is valuable for the company and is running on time, although developers usually override the business analyst when there’s a conflict. The business analyst is typically part of another functional area such as product management and reports up through marketing or a functional business unit. Analysts produce customer-use cases and fill out reams of forms stipulated by the software development life cycle process. Of course, no one actually reads these forms during development, so they’re of marginal utility (except to the QA department, which uses the documents later as a form of self-defense to justify why they’re finding so many problems). Project management is the realm of the project management office (PMO). The PMO is usually part of the financial silo because it controls the budget for projects in each functional area. The PMO is a matrixed organization responsible to both the finance department and other functional areas.

Designers. The design team handles the front-end look and feel of software. It comprises wireframers (who mock up the layout of a screen or web page), to graphical user interface (GUI) designers, to graphic artists. They often fall victim to the siren call of consistency between unrelated products, because they work on a portfolio of projects for all types of customers. Also, since they’re not deeply invested in any particular customer, they often follow industry norms suggesting that there are right ways and wrong ways to build user experiences.

Quality assurance. Despite the obvious importance to the customer of quality assurance, this silo doesn’t get a lot of respect. Like many of the programmers, they’re often located offshore. They start their work long after the software bugs have settled into concrete. Sheridan describes the relationship between QA and the developers this way:

The QA team is usually sequestered in the basement of Building 3, far away from the programmers, as programmers are way too busy to trouble themselves with pesky details like “the software doesn’t seem to work.” The most typical response from programmers? “It worked on my machine.”

Documentation. Their job is to fix the broken user experience through documentation they know in their hearts no one will ever read. (Really. Have you ever read a user manual?)

Other departments. If there’s a regulatory component (like the FDA), or specific security issues (such as software for credit card machines at a mass merchant like Target), more silos and vice presidents will inevitably be involved. If there is a large infrastructure component, then IT infrastructure will be another stakeholder. Finally, there’s almost always a separate team that handles after-sale support and makes emergency software fixes for the customer.

Key performance metrics. KPIs for software companies are almost exclusively internally focused. They measure how much they spend per person per hour; the number of hours per person; whether or not they stayed within budget; and whether they built the software they had spec’d (irrespective of whether or not it’s really useful to the users). The most customer-focused metric is on-time delivery—and even that measurement largely points toward their internal performance.

The Menlo Innovations approach breaks down these silos and organizes entire project teams around the customer. Teams are cross-functional, including all skill sets needed to deliver a project on time and on budget. The company has done away with business analysts from another functional silo. Rather, their “High-tech Anthropologists®” are an essential part of the team, responsible for deeply understanding the customer’s business goals and the user’s need through interviews with the customer and anthropological discovery with the customer’s users; on-site observations of users in their natural environments; and low-tech prototyping of software designs. Before the programmers even start coding, the project team understands how customers will use the software and is aligned and in agreement on what needs to be done.

To avoid the sub-silos that form around technical specialties, Menlo programmers don’t specialize in any specific technology—all of them code in all languages. They also code in pairs, meaning that two people sit at one computer when programming—one person types, and the other reviews the code in real time. The keyboard moves freely back and forth between the pair. The pairs change regularly to ensure that knowledge, skills, and experiences are shared and transferred throughout the company.

Quality is built in at all stages of the project. Programmers write automated test units for their code before they even write the code itself to ensure that they don’t “game” the test to fit the code they’ve written. Moreover, QA members are an integral part of the project team from the start, rather than coming in at the end. And clients come in for a weekly “show and tell” of the new code to ensure that it meets client expectations at all stages of development.

Menlo’s primary metric is purely customer focused: it measures joy for the people it serves. (Seriously.) Of course, the company never meets the people it serves, and these people don’t pay Menlo directly for the work the company does. Nevertheless, Menlo explicitly defines joy this way:

Joy is delivering software to the world that delights the people who use it every day.

The company is even willing to build this metric right into its business contracts. It’s willing to trade away a substantial amount of profit in exchange for equity in the client’s company and royalty in the product it designs and builds. Menlo is willing to bet that a product or service that delights users will drive business results. In 2014, almost 15 percent of annual revenue came from royalties alone. Sheridan explains that this approach can actually cost the company business:

Why would this philosophy get us in trouble with the clients who pay us to do this work? Because if the sponsor is focused on short-term rewards like cutting expenses, delivering quickly no matter what, looking good to their bosses even if they are building the wrong thing, our joyful focus becomes really annoying. Some even fire us for this myopic focus. We’re OK with that.

The ultimate evidence that Menlo’s approach works—in addition to profitable growth every year—is this: the phone (almost) never rings with customer problems. (In fact, I spent three hours there last winter, and there wasn’t a single phone call.) Sheridan estimates that in 14 years of business, the company has had about five calls asking for assistance with serious problems. Five. Most software companies? They get hundreds of calls per day because of problems with their software.3

Some wonder if all this attention to joy and quality is worth it. For Sheridan and Menlo, the question isn’t relevant regarding revenue or profit or growth. It is relevant to joy. Joy, both in the workplace and in the delight of providing an outstanding experience to the customers that use the work of Menlo’s hearts, hands, and minds every day.

Based in Indiana, Aluminum Trailer Company (ATC) is a manufacturer of (you guessed it) aluminum trailers for more purposes than you can probably imagine. Their products include trailers designed for disaster response, mobile command, living quarters, and even food vending. And that doesn’t even include the custom trailers it builds.

Until 2012, ATC was organized, like most companies, into functional silos—sales, design, engineering, manufacturing, customer service, finance, and so on. The silos didn’t talk to each other very much, except to complain when one of the other functions wasn’t responding fast enough to an email. In fact, people in the silos didn’t even see each other very much—one of the salespeople discovered that it took her 101 steps to walk from her desk to the engineering department. That’s about 80 to 100 yards (each way!) in a company with only 160 people.

Those long walks may have been good for exercise, but they weren’t very good for business. Customer service suffered, with emails stacking up in inboxes for two or three days at a time without a response. (With a 200-yard round trip, people didn’t eagerly race across the building to follow up on a message.) The silos also created an “us versus them” mentality between departments, with plenty of finger-pointing and blame when there was a problem or something needed to be redone. Perhaps most perniciously, the siloed approach led people to work more slowly. CEO Steve Brenneman explains it this way:

When people are physically separated and vertically oriented, they can’t see what’s happening in other departments. Let’s say you’re a highly skilled engineer who works fast. You don’t know what the designers or salespeople are dealing with. You just know that there’s not a lot of work for you to do right now, so you take it easy and work more slowly. But if you knew what they were working on, you might be able to help them. Or you might be able to get a jump on the work that will be coming to you in a week, rather than waiting for the tsunami to overwhelm you later.

One final problem with ATC’s vertical orientation was that it didn’t learn from previous work. By treating all types of customer orders the same, and by not sharing information across the functional departments, the company couldn’t create “reusable knowledge.” Brenneman jokes,

We didn’t build trailers; we built snowflakes. We treated every trailer as a one-of-a-kind order. We hoped that the customer would never order that trailer twice, because then we’d have to discover how to do it all over again.

To reduce the number of errors and the amount of time it took to deliver a trailer, Brenneman completely eliminated the departmental silos and reorganized the company horizontally into “value streams”4 around three types of customers. “Value Stream 1” serves customers who want an off-the-rack trailer that requires no (or minimal) changes. “Value Stream 2” serves customers who need slight modifications and tailoring. And “Value Stream 3,” staffed with the most skilled people, serves customers who demand fully customized, highly complex products. (Brenneman somewhat sheepishly acknowledges that these aren’t exactly the most creative names for the teams.)

Each team is made up of a coordinator, salespeople, designers, and engineers. In contrast to the vast physical (and psychological) distances between silos in the old organization, everyone in the value stream sits together, with no walls between members of the team. An internal salesperson on each team coordinates the internal activities needed to generate a price quote for a product and get customer approval. Each team is focused exclusively on one particular type of customer, which means that they’re able to capture and reuse knowledge. (No more snowflakes.) The physical proximity reduces delays when handing off work between people and has completely eliminated the “us versus them” mentality that accompanies vertical thinking and silos. Figure 3.3 shows the team in Value Stream 2.

FIGURE 3.3 Value Stream 2 team.

Finance and R&D still exist as separate departments that provide shared services to the three teams. In finance, the company has no choice, because there are only two people who have the necessary skills. Even though R&D stands alone as a department, it doesn’t get overloaded (like the R&D team at Vaisala, which I’ll describe in Chapter 5) because the company holds regular meetings with all three teams and the R&D group to agree on priorities.

How has the change worked out? Since implementing this new organizational structure, ATC has improved productivity (revenue per man-hour) by 11 percent per year. It also turns around orders faster: it used to take about seven weeks to get ready for an order and one week to make it. Now it only takes two weeks to prep for an order and one week to build it.

Notwithstanding these financial benefits, Brenneman says the most valuable benefit of ATC’s horizontal value stream management is that the end customer is now visible and connected to the whole team at ATC. In the past, only the salespeople knew the customer—office and plant personnel had no connection to their users. Now, everyone sitting in the value streams is doing value-added work for the end customer. His ultimate goal is to have everyone sitting or functioning within the value streams they’ve set up. Faster service, better internal dynamics, fewer errors, higher productivity—what’s not to like?

Fitness programs must be tailored to your specific objectives, or you’ll waste time and energy and fail utterly to reach your goals. In the same way, your organization must be oriented around the specific needs and wants of your customers. Your functional departments must measure and design their work to serve specific customers, not their own internal needs. After all, it’s the customer who keeps score—not the department VP. How are you going to satisfy that scorekeeper?

Here are some steps that will help you shift from a vertically oriented organization built around departments to a horizontally oriented one built around the customer.

List your major customer types and points of differentiation. Think about differences in size, geography, and distribution channels. Consider how, when, and where they use your products or services.

List your major customer types and points of differentiation. Think about differences in size, geography, and distribution channels. Consider how, when, and where they use your products or services.

Interview representative customers for each type. What do they value most? Why? Compare these answers across the different types you’ve identified.

Interview representative customers for each type. What do they value most? Why? Compare these answers across the different types you’ve identified.

Interview people (both VPs and frontline workers) in your functional departments. What specific needs or challenges do they deal with when working with these different customer types?

Interview people (both VPs and frontline workers) in your functional departments. What specific needs or challenges do they deal with when working with these different customer types?

Examine everything you do in each major process through the filter of whether it serves the customer or your own internally focused metrics. What waste can you see? How can you shift focus from working vertically to working horizontally?

Examine everything you do in each major process through the filter of whether it serves the customer or your own internally focused metrics. What waste can you see? How can you shift focus from working vertically to working horizontally?

Create three to five metrics that reflect what’s important for each customer type. (In general, these metrics will be holistic and won’t tie into the metrics you use for your internal measurements.)

Create three to five metrics that reflect what’s important for each customer type. (In general, these metrics will be holistic and won’t tie into the metrics you use for your internal measurements.)

Create a “value stream manager” for each customer type. The value stream manager’s responsibility is to advocate for the customer, not the departmental head. Remember, you don’t have to go as far as Menlo Innovations or Aluminum Trailer and completely get rid of silos. Asics maintained its functional silos but gave me authority and responsibility to advocate for one type of customer. Note that if your customer base doesn’t break naturally into customer types, you may benefit from creating value streams around product families. (For example, if you’re a manufacturer with production split among multiple plants, it may make sense to organize around product families.)

Create a “value stream manager” for each customer type. The value stream manager’s responsibility is to advocate for the customer, not the departmental head. Remember, you don’t have to go as far as Menlo Innovations or Aluminum Trailer and completely get rid of silos. Asics maintained its functional silos but gave me authority and responsibility to advocate for one type of customer. Note that if your customer base doesn’t break naturally into customer types, you may benefit from creating value streams around product families. (For example, if you’re a manufacturer with production split among multiple plants, it may make sense to organize around product families.)