WORKING ON THE RAILROAD

AS THEY DREAMED OF CANALS, Baltimore’s entrepreneurs worked with steam. Mayor George Stiles had been a pioneer in the field. He introduced a small rotary steam engine at least as early as 1814, and later demonstrated its efficacy by using it to power one of the city’s first steamboats and a gristmill for corn.1 In 1813, a steam-powered flour mill was built on a wharf, where it could receive raw wheat at one end and transfer flour directly to the hold of a ship at the other. A steam-powered sawmill began operation at about the same time, and a steam-driven textile mill began operation in 1814. By 1826, the mayor and city council were soliciting proposals to replace the harbor’s horse-powered mud machine with a steam-powered dredge.2

The city may have lost the canal race, but it stood at the cutting edge of antebellum invention. While its businessmen found new uses for steam engines, in 1817, Baltimore became the first American city to light its streets with gas. Delegates to the Internal Improvements Commission of 1825 mentioned “rail roads” as an alternative to canals and turnpikes, and the commission’s final report called on the legislature to create a board of public works to consider, among other things, “what canals and rail roads are practicable.” The Maryland General Assembly did create a board of public works at its next session, in 1826, but the legislation mentioned only roads and canals, not railroads.3

The subject came up again less than a year later when “sundry citizens of Baltimore” gathered “for the purpose of devising the Most Efficient Means of Improving the Intercourse between that City and the Western States.” From the outset, the assembled Baltimoreans seem to have known what their conclusions would be. During their first sessions, “Various documents and statements, illustrating the efficiency of Rail Roads, for conveying of articles of heavy carriage, at a small expense, were produced and examined.” The evidence seemed convincing that the railroad was a superior mode of transportation “over Turnpike roads or Canals.” But to achieve an even higher degree of certainty (and prestige) for this view, the “sundry citizens” submitted their documents and statements to a committee of seven prominent Baltimoreans, who were to examine the collected materials, together with “any other facts or experiments as they may be able to collect,” and then recommend a course of action.4

The committee did not abandon canal building, but its priorities were obvious. Its report recommended a canal from Baltimore “intersecting the contemplated Chesapeake and Ohio Canal within the District of Columbia, and . . . A DIRECT RAIL ROAD FROM BALTIMORE TO SOME ELIGIBLE POINT UPON THE OHIO RIVER.” The “sundry citizens” resolved that “immediate application be made to the legislature of Maryland, for an act incorporating a joint stock company, to be styled ‘The Baltimore and Ohio Rail Way Company.’ ”5

The committee members numbered only about two dozen, but they included some of the most influential members of Baltimore’s business elite. They convened at the home of George Brown, son of investment banker Alexander Brown; the younger Brown would become a director and first treasurer of the B&O. Philip E. Thomas, a local hardware merchant before he became president of the Merchants’ Bank, was chairman of the committee that reported to the sundry Baltimoreans; he would become the first president of the B&O. His brother, Evan Thomas, traveled to England to observe the Stockton and Darlington Railway and came back with decidedly positive impressions. Steam locomotives hauled coal hoppers over the tracks from inland mines in the north of England to the seaport of Stockton. The road soon added passenger service. William Brown, George’s older brother, had been Alexander Brown and Sons’ agent in Britain since 1809. His letters home added to local enthusiasm about the potential of railroads and steam engines.6

John McMahon was one of the youngest participants in the meetings at Brown’s house, and the only elected officeholder in attendance—serving his second term in the Maryland House of Delegates. He was also an attorney, and the job of drafting the new railroad’s corporate charter fell to him. The B&O venture commanded such ready support that the General Assembly approved its incorporation only days after McMahon finished writing the charter. The legislature authorized the B&O to issue $3 million in stock at $100 a share. It reserved 10,000 shares for the State of Maryland and 5,000 for Baltimore City.7

On March 20, 1827, the B&O opened its books to subscribers. On the same day, the city council authorized the mayor to subscribe for $500,000 in B&O shares on behalf of the municipality. The city appointed two directors to the B&O’s board—the presidents of the first and second branches of the city council.8

At its inception, the B&O was not simply a private, profitmaking corporation. Governments—state and local—subscribed half of its initial stock offering. The General Assembly granted the company a tax exemption and claimed the right to set its rates. In short, the railroad was a venture in state capitalism. After Baltimore and Maryland had taken ownership of half the company, the residents of Baltimore rushed to purchase the shares that remained. By the time the company closed its books on March 31, 1828, local residents had signed up for 36,788 shares, more than twice the allocation for private subscribers, so these had to be doled out in fractional shares. About 22,000 Baltimoreans—more than a quarter of the city’s population—purchased stock in the railroad. The B&O was not only a quasi-public corporation; it was a community enterprise. Its primary purpose was not to turn a profit but to restore Baltimore’s advantageous connection with the territory beyond the Alleghenies. The city’s government and citizens would later provide most of the financing for another railroad: the Baltimore and Susquehanna.9 The two imaginary canals conceived to link Baltimore to the Potomac and Susquehanna Valleys would be replaced by a pair of real railroads.

Imagined canals had awakened a spirit of public enterprise in Baltimore. The railroad gave that spirit a tangible vehicle. The B&O project was a unifying focus of public endeavor, and it had majestic scope. Its grandeur commanded awe as far away as Massachusetts, where the Berkshire Star declared that “Pyramids . . . palaces and all the mere pomp of man sink to insignificance before such a work as this . . . a single city has set foot on an enterprise . . . worthy of an empire.”10

The symbolic start of the B&O’s journey was a ceremony on July 4, 1828, when 90-year-old Charles Carroll of Carrollton, after prayer and oratory, sank a spade into the ground near the corner of Pratt and Amity Streets, where the railroad would lay its “first stone.” (The railroad initially used granite ties on its 13-mile leg from Baltimore to Ellicott’s Mills and on most of its tracks in the city.) On the same day, President John Quincy Adams was engaged in a similar ritual in Georgetown, the starting point for the Chesapeake and Ohio Canal. The president’s execution of the ceremony ran into trouble. His spade hit a stump or a tree root just under the surface, and it required several attempts for him to produce a quantity of dirt worthy of the occasion.11

The B&O Railroad and C&O Canal were obvious competitors. The managers of the C&O made an early decision to challenge the B&O in court before their company had to face the railroad in the market. The legal struggle turned on Point of Rocks, where the Potomac Valley narrowed, and the level ground available for construction on the Maryland side of the river seemed insufficient to accommodate both a canal and a railroad. The B&O’s attorney was John H. B. Latrobe, son of the architect Benjamin Latrobe, who was assisted by the aristocracy of the American bar, including Daniel Webster, William Wirt (future US attorney general), Roger B. Taney (future chief justice of the US Supreme Court), and Reverdy Johnson (future US attorney general and senator). Neither the C&O nor the B&O had reached Point of Rocks by the time the C&O Canal Company filed suit in Frederick. By January 1832, the dispute reached the Maryland Court of Appeals, which delivered a decision granting the Canal Company exclusive construction rights on the left, or Maryland, bank of the Potomac. The majority opinion rested on the contention that the C&O Canal had inherited the rights set out in the charter of the defunct Potomac Company. Since those grants were made in 1784, the canal’s claim took priority over the B&O’s.12

The dispute migrated to the General Assembly, which had financial stakes in both railroad and canal. It imposed a compromise. The B&O’s double-track line would become single-track at Point of Rocks so that it would take up only a 20-foot strip of the riverside terrace. The C&O would dig its channel in the 40 or 50 feet remaining. When the railroad reached Harper’s Ferry, the B&O would have to abandon the Maryland side of the Potomac and cross the river by bridge. The work of finding and surveying a feasible route beyond Harper’s Ferry was assigned to Benjamin Latrobe, Jr., John’s brother. Benjamin also designed the bridge at Harper’s Ferry.13 These inconveniences did not prevent the railroad from reaching Cumberland in 1842, eight years before the canal had been dug that far, and unlike the C&O, the B&O continued beyond Cumberland to the Ohio River.

CORPORATE CULTURE

Mayor Jacob Small celebrated the progress of the railroad. Baltimore’s government and its citizens, he said, were “deeply concerned, both as regards their immediate interest in the stock of the company, and [about] the effects which this splendid scheme of internal improvements, if it is successfully accomplished, will not fail to produce in the future prosperity of our City.”14 But for all the celebration, there was an undercurrent of uneasiness, at least on the city’s side, about its partnership with the B&O.

The first curious note in the relationship between city and railroad was a resolution introduced in the second branch of the city council in February 1828, little more than a month after the mayor’s celebratory remarks. It authorized him to dispose of the city’s shares in the B&O whenever it seemed advantageous to do so. The stock was selling well above par, and the resolution held that the city’s installment payments on its $500,000 stake in the railroad imposed an undue burden on taxpayers. The sale of the city’s B&O shares could provide the funds needed to cover the cost of shares subscribed for but still to be purchased.15

The measure did not pass, but it was followed by others suggesting a lack of transparency in the relationship between the city government and the corporation it had helped to create. City officials participated directly in the railroad’s governance. The mayor represented the city at the B&O stockholder meetings; the presidents of the city council’s two branches held seats on the railroad’s 14-person board of directors. But their participation in corporate governance did not give them access to the railroad’s plans on matters vital to Baltimore. The mayor and council were concerned in particular about the route that the railroad would take through the city and the location of its “depot or depots.”

Solomon Etting, president of the first branch of the council, suggested that the railroad call a meeting of its board of directors to decide “the Point at which it shall enter the City—and also upon the direction of its continuance through the City, to its point of termination or general depot.”16 The directors met and approved a resolution instructing the engineers to plot the best course from Point of Rocks on the Potomac to Baltimore’s city limits and “terminate at a point calculated to distribute the trade throughout the Town as now improved.” Etting wrote to Mayor Small expressing “regret that this resolution leaves undefined the point at which the Rail Road will enter the City, or the point at which it shall terminate within the City.”17

If the B&O planned to locate as close as possible to tidewater, it would choose a point on the Patapsco at the mouth of its Northwest Branch and south of Baltimore, from which the railroad could have followed the Patapsco westward toward the Potomac. Etting and other city officials were concerned that this would lead to intense commercial and industrial development several miles south of the city limits, and they were not about to invest $500,000 of their constituents’ taxes to promote a competing commercial center.18

The city was pursuing another strategy designed to lock the railroad’s terminal facilities into place within the limits of Baltimore. In March 1828, the B&O had placed a newspaper advertisement announcing that it was interested in acquiring “suitable grounds, or sites for depots, or points of stoppage . . . at any place within or near the city of Baltimore.” Mayor Small sent a clipping of the notice to the city council, adding that “the City is in possession of a large property East of the Jones Falls . . . which might suit the views of the Company.”19 The property, at Fell’s Point, was the “City Block,” created by the municipal mud machines out of spoil dredged from the bottom of the harbor. At first, the council was disposed to sell the real estate to the railroad, but the sale was converted into a donation, apparently with the hope that the gift of free land would make the city irresistible as the site for the railroad’s terminal facilities. The council authorized the mayor “to convey to the Baltimore and Ohio Rail road company certain property &c” without any pecuniary consideration.20

The city did not complete the property transfer until 1832, but the gift of real estate seems to have satisfied the needs of both parties. The land provided the B&O with “direct communication between the railway and the shipping in the harbor,”21 and the railroad’s foothold in Baltimore reassured local officials that the city would be able to capture commercial and industrial development stimulated by the railroad terminal. The B&O was already building a depot on the west side of the city on a 10-acre tract of Mount Clare, a Carroll family estate, also donated to the railroad. In time, the B&O would build its shops and a roundhouse here. And at Locust Point, across the harbor from its Fell’s Point depot, it would lay down a gigantic railyard with towering grain elevators and spindly coal piers that would carry gondolas high enough to tip their contents into the holds of ships.

INVESTING IN UNKNOWNS

The B&O’s negotiations with the city had given the municipal corporation its first experience of dealing with a big business corporation. Public officials, accustomed to handling the concrete grievances of individual citizens, now engaged in complex, corporation-to-corporation transactions. The municipal and railroad corporations were like nations conducting diplomatic relations rather than officials dealing with clients. The B&O introduced a new impersonality into Baltimore’s politics, a development soon to be accentuated by the institutionalization of political parties and elaboration of ideologies during the Jacksonian era. Both were political abstractions from the personal. But it was not just corporate impersonality that complicated communications between municipal and business corporations. Even if the B&O had tried to be completely clear about its plans, it could not offer straightforward answers to all of Baltimore’s questions.

Railroad technology was in its infancy, and railroads were among the first large-scale industries in the United States. Basic questions about equipment and organization remained unsettled. What should rails look like? At first, they were just iron straps fastened directly to granite or wooden ties; later, the iron straps were fastened to wooden stringers secured to the ties. The ends of the iron straps, however, tended to curl upward and break loose from the stringers when subjected to heavy loads. These loose rails were called “snakeheads,” perhaps because they were so deadly. A loose snakehead could derail an engine or erupt through the floor of a passenger car to maim and kill its occupants. Snakeheads became a problem when the B&O shifted from horsepower to heavy steam engines, a transition not completed until 1836. Even after 1836, a municipal ordinance required horse-drawn trains within the city limits, and an agreement with the C&O required the B&O to use horsepower in the narrow pass from Point of Rocks to Harper’s Ferry. (Steam locomotives frightened the horses and mules that pulled the canal boats.)22

Even a horse-powered railroad seemed a remarkable improvement in transportation to passengers of the 1830s. During the first phase of its construction, the B&O offered public officials and prominent Baltimoreans junkets by passenger car from Pratt Street to the Carrollton Viaduct, a bridge that still carries railroad tracks across the Gwynn’s Falls in far southwest Baltimore. The Baltimore American marveled that a single horse could pull a carriage occupied by “twenty-four ladies and gentlemen . . . at the extraordinary rate of fifteen miles an hour!”23

Though Peter Cooper’s Tom Thumb is supposed to have lost its famous race with a gray mare, Cooper persuaded at least some of the B&O directors that steam locomotion was feasible on the railroad’s westward path to the Alleghenies. Cooper had a tangible stake riding on the outcome of the race, but not on the locomotive itself. He had come to Baltimore from New York and, with two partners, purchased 3,000 acres on the waterfront just east of the city. It had once been the property of a Baltimore sea captain engaged in the China trade. He called his estate Canton, the name that the area carries today. Cooper was convinced that the operations of the B&O would send the area’s land prices soaring. He became a director of the Canton Company, which presided over conversion of the captain’s estate into one of the country’s earliest industrial parks—10,000 acres on which the corporation hoped to see the construction of “wharves, ships, workshops, factories, stores, dwellings, and such other buildings and improvements as may be deemed necessary, ornamental, and convenient.” When the grading and draining of Cooper’s land turned up iron ore deposits, he converted his real estate investment into an industrial venture. Trading much of his land for stock in the Canton Company, Cooper retained enough waterfront real estate to accommodate the furnaces and forges of the new Canton Iron Works, poised to sell iron rails to the B&O.24

The success of Cooper’s ironworks and the value of his shares in the Canton Company depended on the success of the railroad, and the fortunes of the B&O, he thought, hinged on the decisive advantages of steam power. But the B&O directors were skeptical about the use of steam locomotives, even though the engines had proven themselves in England. The route from Baltimore to the Potomac River had to follow the winding bed of the Patapsco, then the turns of the Potomac, and after that there were mountains to be circumvented. Settled opinion held that steam locomotives could not handle tight curves. On the 13-mile run from Baltimore to Ellicott’s Mills, Cooper showed that his Tom Thumb—though admittedly a very small steam engine—could negotiate curves. Early in 1831, the railroad’s directors offered a prize of $4,000 for the best four-wheeled locomotive of three-and-a-half tons, more than three times the weight of Tom Thumb. Phineas Davis, a former watchmaker from Pennsylvania, won the competition and went on to build several other locomotives for the B&O. Davis’s career as an engine builder was cut short in 1835 when he was killed in the derailment of his prize-winning locomotive.25

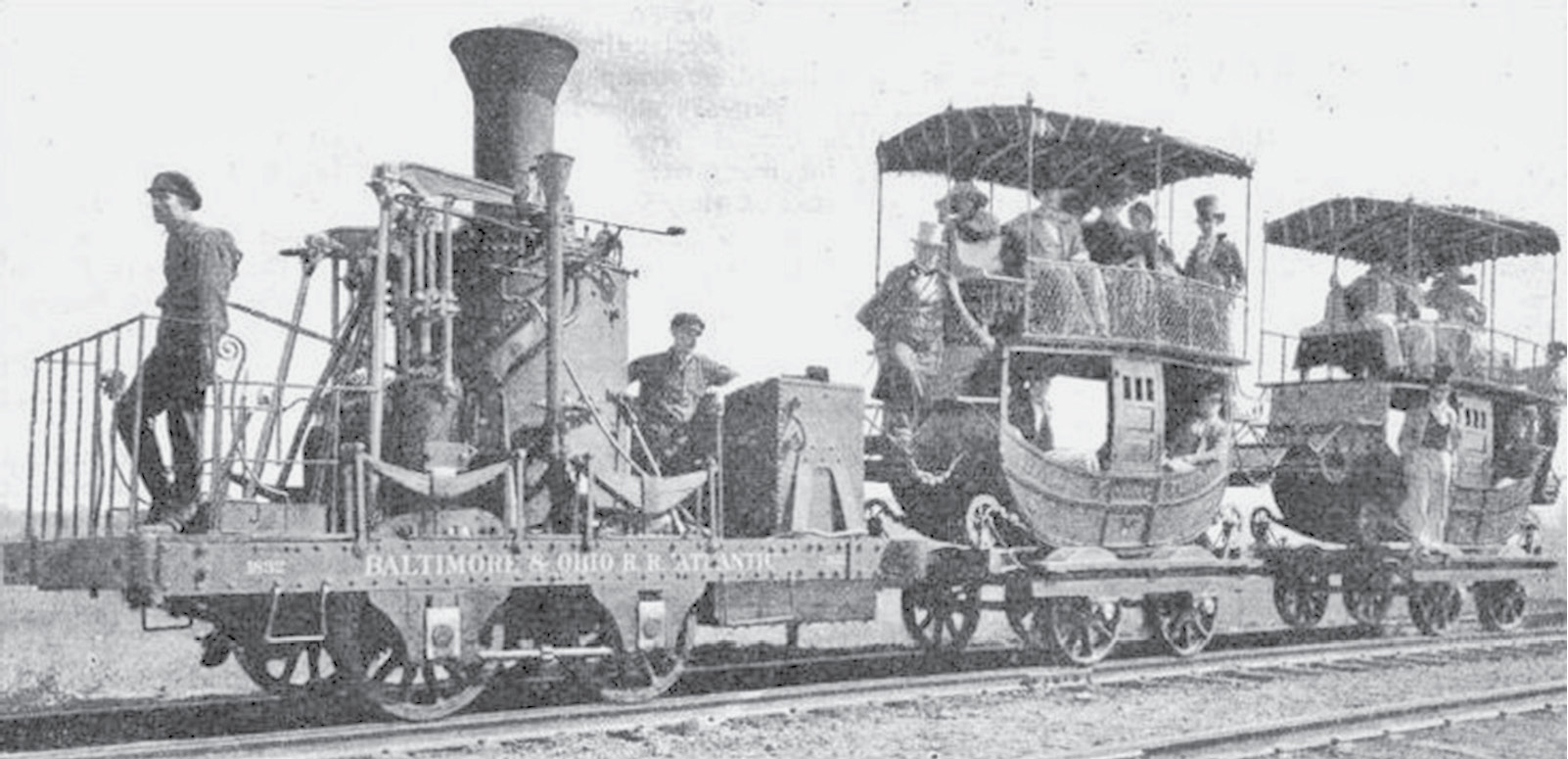

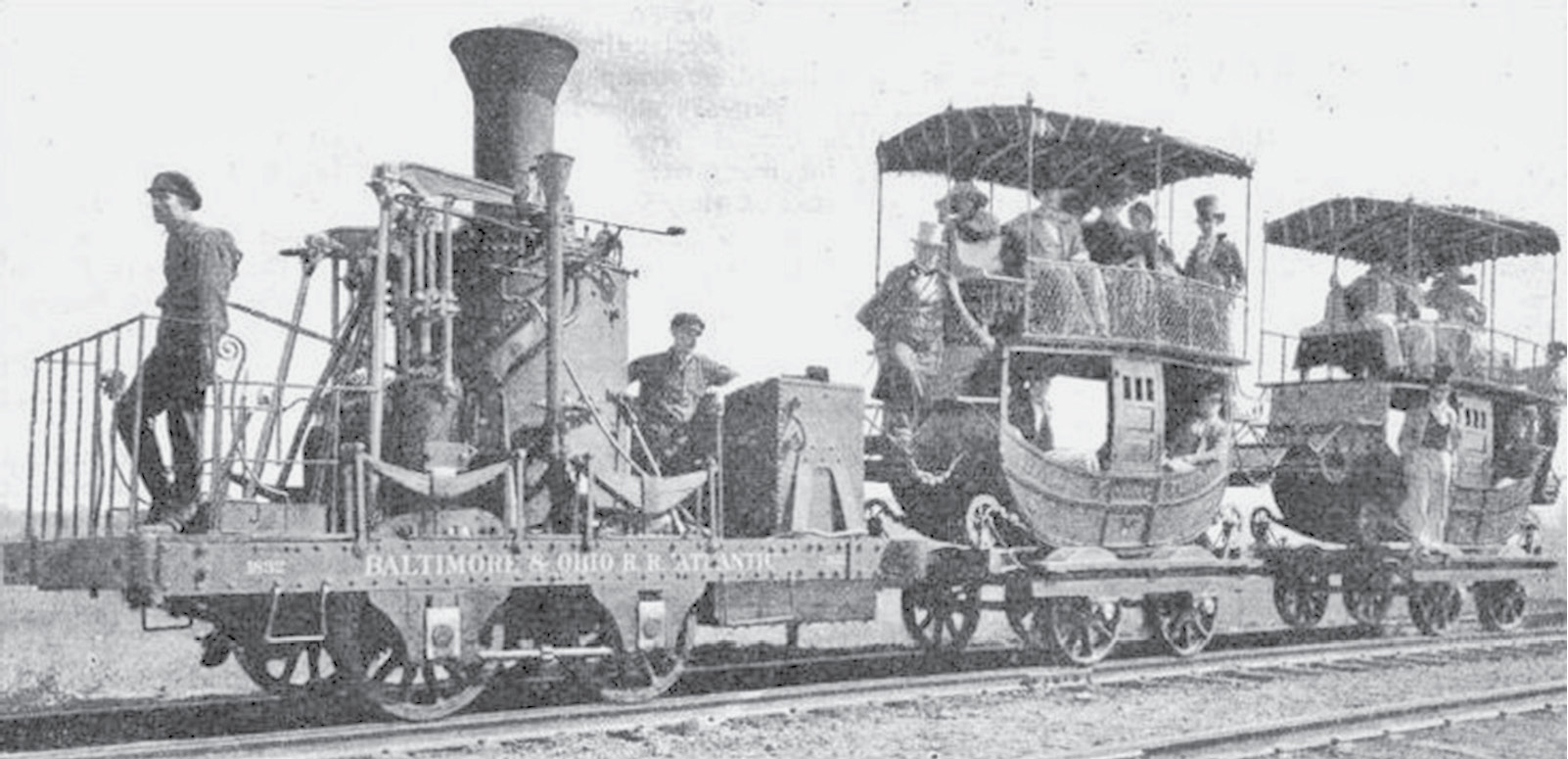

A replica of the Atlantic, the second locomotive built by Phineas Davis for the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad in 1832. The B&O built 20 other locomotives based on Davis’s design.

Some of the B&O’s most vital innovations were administrative rather than mechanical. The railroad was a multistate corporation operating on an unprecedented scale. It opened the age of big business and managerial capitalism. The corporation’s counsel, John H. B. Latrobe, weighed in on crucial matters of administrative structure. He acknowledged that the company’s president could not possibly exercise personal supervision over the railroad’s extensive operations, but he rejected a proposal to appoint an assistant president because it would “amount to dividing between two persons the duties which are performed in other enterprises by one.” Latrobe wanted the company to be led by a “single mind.” Instead of appointing an assistant president, he proposed to organize the company into three divisions, all of which would report directly to the president. Two of these divisions would consist of subdivisions. Under the chief engineer, for example, there would be a superintendent responsible for surveying the route and acquiring land for the right of way; a superintendent of construction, responsible for laying the track, building the bridges, and boring the tunnels; and a superintendent of machinery, in charge of building locomotives and rolling stock. After the road reached Cumberland and prepared for its final surge toward the Ohio River, the company developed an even more elaborate structure.26 Its annual reports were regarded as textbooks for the railroads that followed. In 1835, the American Railroad Journal named the B&O the “Rail Road University of the United States.” It enabled its successors to save time and money that might have been wasted on technological and organizational dead-ends.27

Uncertainties about technology and organization translated into doubtful estimates of time and cost. Building the railroad from Baltimore to Wheeling took more than 25 years and millions of dollars more than expected. Some of that time was spent in the B&O’s legal skirmish with the C&O Canal Company. The agreement under which the two corporations shared the Potomac Valley right-of-way west from Point of Rocks required the B&O to stop laying track past Harper’s Ferry until the C&O had reached Cumberland. The railroad survived the halt because, by reaching Harper’s Ferry, it was also able to make a connection with the Winchester and Potomac Railroad, which brought the B&O freight and passengers from the length of the Shenandoah Valley. It also used the hiatus to build a branch line from Baltimore to Washington. Together with its short branch line to Frederick, completed in 1831, these links enabled the railroad to generate revenue even while it made no progress toward its intended destination at the “western waters.”28

Just to reach Harper’s Ferry, however, the B&O needed an accelerated infusion of cash. In 1833, it persuaded the Maryland legislature and the City of Baltimore to step up the schedule of installment payments on their stock subscriptions. In 1836, the General Assembly released the B&O from its obligation to stand still while the C&O burrowed toward Cumberland. But the railroad could not proceed until Baltimore added a subscription of $3 million to its original stake of $500,000. The state agreed to provide another $3 million, in three annual installments. The B&O borrowed additional money to cover cost overruns on the line to Harper’s Ferry, and extensive repairs were needed along the existing line because the rails dated to the railroad’s “experimental” phase and had not been built to stand up to heavy traffic and the weight of locomotives and rolling stock.29

DEBTS BEFORE DIVIDENDS

The task confronting the founders of the Baltimore and Susquehanna Railroad seemed less daunting than the B&O’s project. Though the Susquehanna line would have to cross high ground between the valleys of the Patapsco and the Susquehanna, no mountain ranges separated the railroad’s city from its river. But it encountered a political obstacle in the Pennsylvania state legislature, whose members were understandably reluctant to charter a railroad that threatened to divert commerce from Philadelphia to Baltimore.30

In 1828, the Maryland General Assembly authorized Baltimore to purchase as many as 2,000 shares of the Baltimore and Susquehanna, with a par value of $50 per share; an equal amount was reserved for the State of Maryland. The city council was more wary about making this investment than it had been for the B&O. A committee recommended that the city hold back its money until the Baltimore and Susquehanna had received a charter to operate in Pennsylvania,31 but the arrangement finally adopted would have the city pay only $2,000 toward its subscription of $100,000—one dollar on each $50 share. Nothing more would be advanced until the railroad demonstrated that “individuals and private corporations” had submitted subscriptions for stock amounting to $250,000 and that each purchaser had advanced at least as much cash per share as Baltimore.32

In return for its stake in the railroad, Baltimore could appoint one of its councilmen as a director of the company. The appointment may have given the city a voice in running the railroad, but it also created an advocate for the railroad in the city council. From his first report, in 1830, Councilman John Diffenderffer reassured his colleagues in city government that all was well with the railroad, even though it remained unclear whether private stock subscriptions had reached the $250,000 minimum necessary to unlock further payments from the city.33

When George Winchester, president of the Baltimore and Susquehanna, finally informed the mayor and council that his company had met the $250,000 requirement, he had something further to ask of the city. The railroad’s directors wanted the council to “advance the credit of the city” as security for their company’s debts. This financial vote of confidence “would give the company the Stability that would insure the accomplishment of its great object—the Salvation of the most important branch of trade now left to the city.” This and “perhaps one small installment more” would “put in operation the first division of the road from the city to the lime stone region” north of Baltimore. The railroad’s capacity to carry bulk cargoes would significantly reduce the cost of materials such as limestone, lime, and marble. Together with passenger traffic and the carriage of freight “to and from the various mills and factories upon the Jones’ Falls,” the marble and limestone trade would, Winchester claimed, enable the railroad to generate annual revenue of $25,000 without having to cross the still impenetrable legal barrier that kept the company from entering Pennsylvania.34

Winchester also hinted that he was having trouble getting the state government to back his railroad and that the city’s support might “insure to us a subscription on the part of the state for the amount reserved for her use.” But there was good news from Pennsylvania, where information from “authentic sources” indicated that “all opposition to the passage of the charter . . . will be withdrawn at the next session.” In fact, four years would go by before Pennsylvania granted the Baltimore and Susquehanna the right to operate north of the Maryland line, and even then the company could not extend its tracks to its original objective on the Susquehanna River, only to the town of York. A Pennsylvania-based railway would provide a link to the river and to the web of canals and rails that stretched north and west from Philadelphia, but the Susquehanna line would not get guaranteed and permanent access to this branch until 1837, seven years after Winchester’s hopeful report.35

Councilman Diffenderffer remained stalwartly optimistic about the railroad’s prospects. Even if York were to be the end of the line, he said, “the wealth and population” of the area “would of themselves justify the construction of a railroad thereto and its extensive commercial relations with Baltimore and the fertility of the surrounding districts would induce an ample revenue to such a work.” The possibility of a connection to the Susquehanna Valley opened up possibilities more promising than those that lay beyond the Alleghenies to the west. The western trade had once given Baltimore prosperity. “To retain its secure possession,” wrote Diffenderffer, “has been the object of her anxious care and her most earnest endeavors and for that object millions have been expended; but as yet in vain.”36 Diffenderffer did not mention the B&O by name, but the implication was clear: the Baltimore and Susquehanna might offer a more proximate and reliable return for the city than the other railroad.

Some city council members may have shared Diffenderffer’s hopes for the Susquehanna line. Four months after receiving his report, in April 1835, the council agreed to offer security for any interest payments that the Baltimore and Susquehanna owed to the State of Maryland.37 The city tied its fortunes even more firmly to those of the railroad two years later, when the company exhausted its resources with one-third of the line from Baltimore to York still incomplete. The city added another $600,000 to its original investment of $100,000. The commissioners of finance issued still more city stock to cover the payment. A year after that, in 1838, the railroad once again ran out of money. Baltimore provided a loan of $150,000, together with a promise to pay an additional $100,000 to the railroad when it completed the line to York. Yet another issue of city stock covered the loan. In return, the city gained three additional council members to serve with John Diffenderffer on the railroad’s board of directors.38

Railroads had once seemed to offer the city a new route to municipal solvency, but an 1836 report of the city council’s Committee on Ways and Means explained how they had placed Baltimore on a fiscal treadmill. The commissioners of finance received an annual appropriation of $27,000 to cover debt service and reduction, but loans and stock purchases for railroads added so much to municipal borrowing that the entire sum went for interest payments. According to the committee, “The amounts of the demands of the Rail Road companies, and the period at which the City would derive a profit from her subscriptions to these companies being uncertain, it became impossible to limit the payment of interest and redemption of the City Debt at any given sum.”39

The city debt exceeded $1 million in 1836 (equivalent to $21.5 million today), on which its annual interest payment was almost $54,000 ($1.26 million). Baltimore had gotten on the train and could not disembark without losing its substantial “subscriptions” and any prospect of a golden return on investment that would erase debt and taxes.