CITY AT WAR

President Lincoln called a special session of Congress in 1861. His purpose was to win congressional approval for the funds he needed to wage war. On June 13, Maryland held a special election to choose its representatives for the session. To rule out apprehensions about military interference at the polls, General Banks assured Mayor Brown that Union soldiers would be confined to their posts on election day “except for those who are voters under the Constitution and laws of Maryland.” This category was rather large. Three Maryland regiments were granted leave to exercise the franchise. In spite of their presence, secessionists and southern sympathizers seem to have campaigned freely and without military interference. A Southern Rights convention nominated a former ambassador to Mexico to run in Baltimore’s Fourth Congressional District.1 But Unionists carried every district in the state.

In Baltimore, the Unionist candidate in the Fourth Congressional District was Henry Winter Davis, the Know-Nothing orator and current incumbent. His popularity had suffered since his last election. When he first took his seat in the House, in 1856, he had conceived a grand strategy for averting the crisis about to consume the country. Davis envisioned a coalition of southern Whigs and Know-Nothings with northern Republicans, uniting to defeat secessionist Democrats. The southern Democrats had already shown their hand by threatening to walk out of the country if abolitionist Republican John Fremont should be elected president.2

In one of several attempts to forge his alliance between southerners and northerners, Davis became the only representative from a slave state to vote for New Jersey Republican William Pennington for Speaker of the House, in a closely fought contest. Without Davis’s vote, Pennington would not have become Speaker. Northern newspapers hailed Davis as a hero. The Maryland House of Delegates censured him by a vote of 62 to 1.3

Davis’s constituents turned against him as well. He lost the Fourth District to Henry May, who styled himself an “Independent Unionist.” May had previously been a Democratic member of Congress, who backed up his claim to party loyalty by declaring that he had never voted for a Whig in his life. He was ejected from his seat when Davis rode the Know-Nothing tide into the House of Representatives in 1855. May’s first public appearance as a Union man occurred when he turned up at a Unionist meeting in Baltimore about 10 days before he won the party’s nomination in the Fourth District.4

Congressman May’s return to office began badly. Before he could take his seat, a Wisconsin congressman introduced a resolution instructing the House Judiciary Committee to investigate allegations that May had been “holding criminal intercourse and correspondence with persons in armed rebellion against the Government of the United States.” The evidence against him came from articles in Richmond and Charleston newspapers suggesting that May visited Richmond to discuss the possible secession of Maryland and the readiness of 30,000 armed Marylanders to join the Confederate cause. The Judiciary Committee was unwilling to condemn May on the testimony of Confederate newspapers, and May himself was not present to defend himself because he was still in Richmond recovering from an illness.

When May finally occupied his seat in the House, he was invited, by unanimous consent, to offer a “personal explanation” of his recent activities. May complained that the charges made against him were “an unparalleled outrage on the privileges of a Representative.” But he quickly veered from self-justification to a condemnation of the military authorities who had become the tyrants of Baltimore. His constituents, he said, were “bound in chains; absolutely without the rights of a free people in this land; every precious right belonging to them under the Constitution, trampled into the dust.” A succession of congressmen rose to complain that May had strayed from personal explanation to political denunciation. But he was allowed to proceed. He presented a memorial from the imprisoned police commissioners of Baltimore. Then he instructed the clerk to read into the record Marshal Kane’s report of his efforts to protect the Sixth Massachusetts on its march along Pratt Street. Asked directly what he was doing in Richmond, May explained that he was linked to Virginia by ties of family and friendship, and he had gone there “to inquire into the disposition of the people of the South; to mingle freely with them . . . and in the sacred office of pacificator, endeavor to avert, assuage, or terminate this awful civil strife.”5

Congressman May voted against the $100,000 appropriation to pay federal police in Baltimore. He was not the only Marylander to do so. Senator Anthony Kennedy also opposed it, arguing that Baltimore’s own police force should return to service. May, however, referred to the police appropriation as the “wages of oppression.” He introduced one of several resolutions demanding that President Lincoln explain the arrest of Baltimore’s police commissioners. Another of his resolutions called for an armistice between the Union and the Confederacy and negotiations “to preserve the Union, if possible, but if not, then a peaceful separation.”6

In September 1861, Henry May was arrested by order of the secretary of war. May’s brother wrote to President Lincoln pleading for the congressman’s release. May had been confined to a casemate at Fort McHenry with 32 other prisoners, but later transferred to Fort Monroe and then Fort Lafayette. He was set free on the grounds of failing health, but returned to his seat in the House. An attempt to expel him from Congress was unsuccessful.7 But the Fourth District’s voters removed him from office at the end of his term and gave his seat back to Henry Winter Davis.

DISAPPEARING DEMOCRATS

Just as Henry May found it expedient to leave his Democratic past behind and reinvent himself as an Independent Unionist, Baltimoreans in general abandoned the Democratic Party. In October 1861, there were no Democratic candidates for the first branch of the city council. One Unionist candidate stood for election in each of the city’s 20 wards. Only four of them faced any opposition, and the challengers, like Henry May, identified themselves as Independents, not Democrats. The Unionist candidates defeated all four of them.8

Baltimore’s Union Party held itself apart from the small contingent of local Republicans because it regarded Republican free-soilers—“Black Republicans”—with as much distaste as it did secessionist fire-eaters. Abolitionists and secessionists were held responsible for the rift that resulted in warfare between North and South. The objective of Baltimore’s Unionists was to sidestep the issues that would drag Baltimore into the deadly center of the storm consuming the nation. To that end, the party sought candidates with neutral political records or none at all. Baltimorean Augustus Bradford was one of these. He had been elected clerk of the city’s circuit court as a Whig, but retired from politics during the 1850s and was conveniently free of any public record on the nasty divisions of that decade. He was elected governor overwhelmingly at the end of 1861, succeeding Thomas Hicks, the last Know-Nothing governor, who went on to become a Unionist US senator. The Unionists (including many former Know-Nothings) also swept the state legislature and judicial elections. There was little evidence that the result reflected military interference. Even states’ rights sympathizers described the election as “quiet” and “free from molestation.”9

In fact, Baltimoreans themselves seemed just as ready as the military to impose restrictions on the political freedom of local residents. In July 1862, Governor Augustus Bradford presided over an “immense Union meeting” in Monument Square, where one speaker after another warned the audience to be vigilant in detecting the treasonous crimes of their disloyal neighbors. Bradford himself warned of “the horde of traitors in our midst.” Another speechmaker equated insufficient dedication to the Union cause with treason. This was, he said, “no time to hesitate and doubt . . . to hesitate was to die and to doubt was to be damned. To hold back was treachery, and treachery should meet the traitor’s doom.” The meeting closed with the approval of a resolution recommending, among other things, that the property and slaves of rebels should be confiscated. It also charged that some recipients of local government patronage and contracts were “men and firms notoriously disloyal, and not a few of them actually engaged in aiding the enemies of the government.” The resolution’s final section demanded that the commander of the local military district administer an oath to all men over 18 years old. They were to pledge “true allegiance to the United States, its Constitution and its laws,” renounce any “faith or fellowship with the so-called Confederate states,” and pledge “property and life to the sacred performance of this oath of allegiance.”10

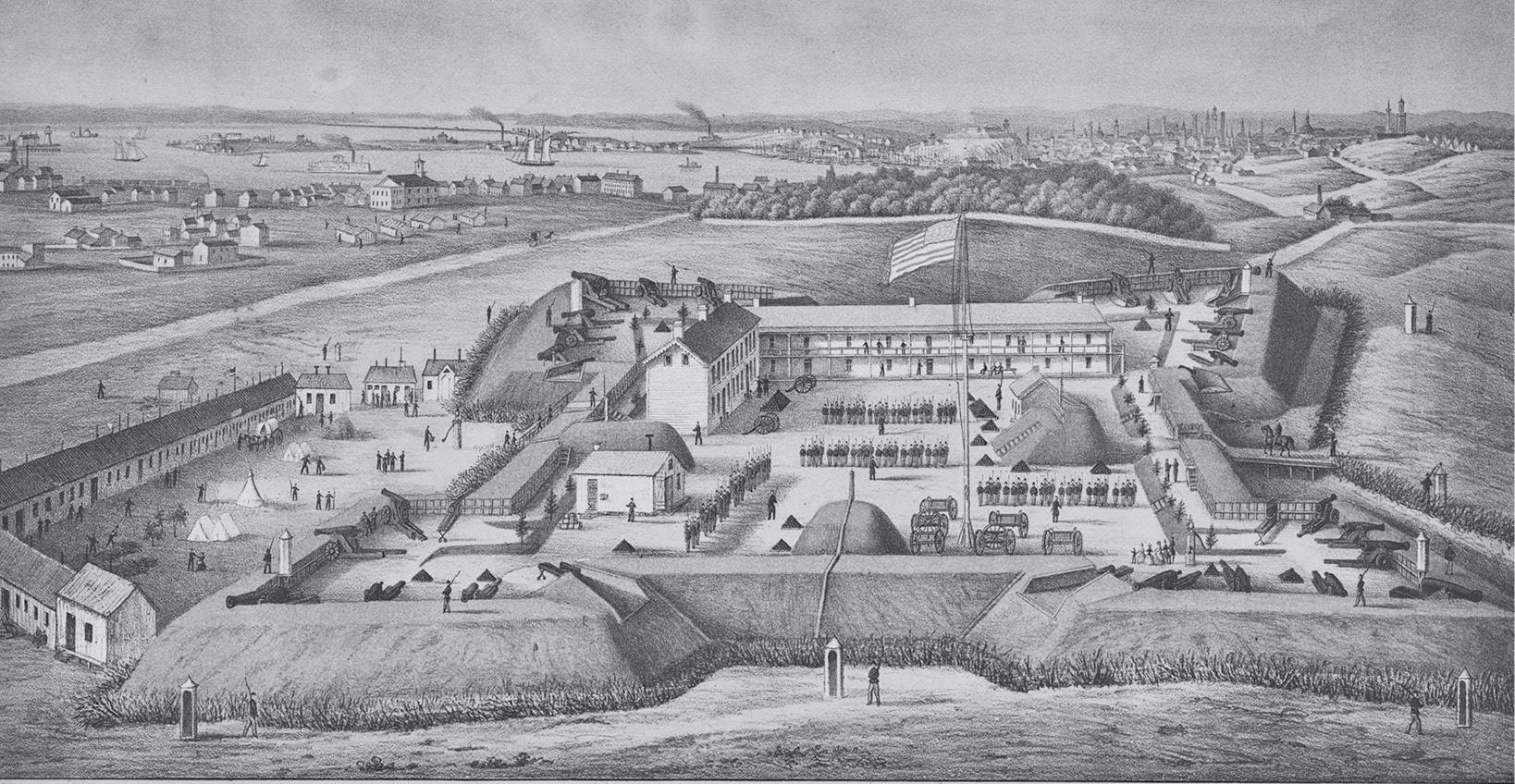

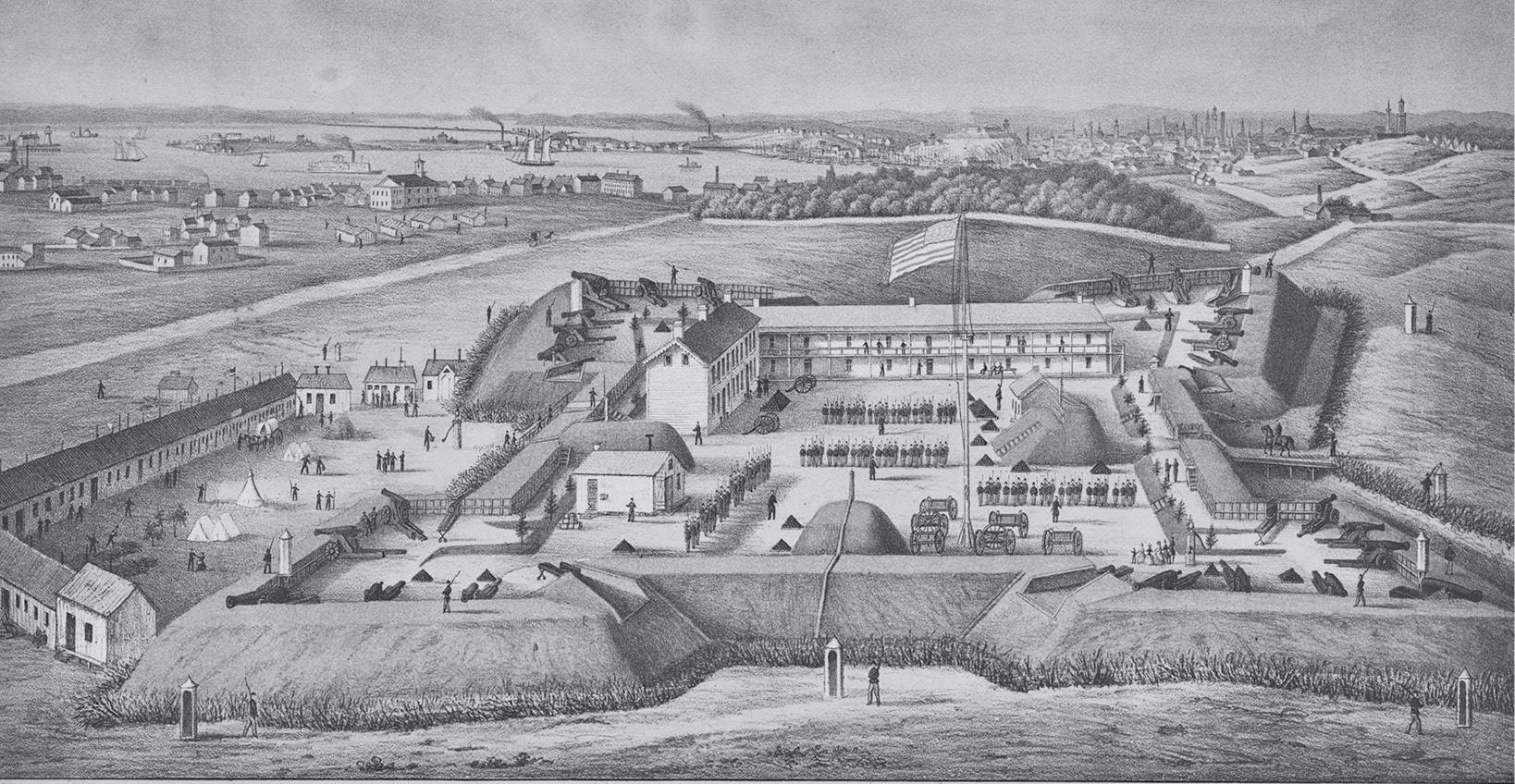

Fort Marshall, one of several federal strong points in occupied Baltimore. The fort was located in the city’s southeast, in a neighborhood known to current residents as Highlandtown. Courtesy Enoch Pratt Free Library, Cator Collection

A few days later, the first branch of the city council adopted a resolution of its own, requesting General John E. Wool, commander of the “Middle Department,” to administer the oath “to all the citizens of the City of Baltimore at the earliest possible period.” General Wool had been seated on the platform at the Monument Square rally. His remarks were notable for their brevity. He said that his business was not to speak but to conquer the enemies of his country. When presented with the city council’s proposal for a “test oath,” he declined to make use of the loyalty pledge. Its enforcement, he said, might “send twenty thousand men to swell the army of Jefferson Davis.”11

Wool was not averse to intervention in local politics. Shortly before the mass meeting in Monument Square, he suggested that a majority of the city council’s second branch should resign because they had failed to approve an appropriation of $300,000 to provide bounties for local volunteers who enlisted in the Union Army. All of those who had opposed the appropriation followed his suggestion.12

Union military authorities had begun their occupation of Baltimore by making arrests to crush subversion. Now they made suggestions. Suggestions succeeded for much the same reason that Know-Nothing thugs had been able to suppress opposition voters without resort to physical force. Like the Know-Nothings, the Union Army had demonstrated that it was in control of the city and that defiance of its authority was futile. In fact, the Union Army had transformed Baltimore into something just short of a military base. By war’s end, there were nine military hospitals in the city. At least a dozen Union camps occupied the parks, squares, and fields in and around Baltimore. There were almost as many fortified positions, most of which were defended by artillery pieces. The most important of these were Fort McHenry (72 guns), Fort Federal Hill (47 guns), and Fort Marshall (60 guns), on high ground in southeast Baltimore in the area later known as Highlandtown. Taken together, these three fortresses could rain shells on the entire city and all of its rail lines.13

The artillery pieces remained silent. Baltimore’s political authorities needed no prompting from Union generals to embrace the Union cause. Political circumstance had engendered a new consensus. Many Confederate sympathizers had left town, and those who remained seem to have recognized that staying put meant staying quiet.

WAR AND POLITICS

The Unionists’ one-party rule in Baltimore was a bit less than it seemed. The Unionists never achieved unity. The only principle they held in common was opposition to secession.14 Some opposed both secession and slavery. Others opposed secession but not slavery. Still others opposed secession but also opposed the use of coercion against the Confederacy as a means of defeating it. There were Regular Unionists, Independent Unionists, Conservative Unionists, Unconditional Unionists, and Conditional Unionists.15

Military conflict, however, constrained factional strife. Confederate incursions into Maryland kept the city and its military forces on alert. The deadly encounter at Antietam in 1862 did not directly threaten Baltimore. The battlefield was 75 miles away in Washington County, but some residents claimed they could hear the rumble of artillery, and Antietam’s wounded flooded the city along with Confederate prisoners. Gettysburg hit closer to home. J. E. B. Stuart’s cavalry was reported to have come within eight miles of Baltimore’s city limits. Thousands of militiamen were put to work on the city’s fortifications. Six thousand pro-Union members of the Loyal Leagues were armed, issued three days’ rations, and posted to the outer defenses. Mayor John Lee Chapman urged residents to meet in their wards to organize companies for defense of the city. Major General John Schenck, who commanded the US Army’s Middle Department from his base in Baltimore, imposed martial law and announced that “peaceful citizens are required to remain quietly in their homes.”16

Another scare came in 1864, when Confederate General Jubal Early raided Maryland to relieve Union pressure on Richmond. A Marylander under Early’s command, Major Harry Gilmor, led a detachment of Confederate cavalry on raids around Baltimore, approaching the city’s limits on Charles Street, where his men burned Governor Bradford’s country home—retaliation for Union troops’ burning the home of Virginia’s governor. On York Road they clashed with a Union cavalry detachment. Riding east to Magnolia Station in Harford County, Gilmor’s men captured and destroyed two trains and burned several bridges. After the war, Gilmor would become a Baltimore police commissioner.

The proximity of the Confederate forces during the Gettysburg campaign may have contributed to a new severity in the military rule of Maryland. Preparing for the state election of 1863, General Schenck issued “General Order No. 53.” It represented a departure from his predecessors’ announced policy against military interference in elections. Schenck’s order instructed his men to arrest anyone “found at, or hanging about, or approaching any poll.” If voters were suspected of disloyalty, Schenck’s men could demand that the election judges administer an oath of allegiance, as specified in Order No. 53. This included a pledge to adhere to the federal government and its Constitution in preference to any law or resolution of the state legislature and prohibited “communication with . . . any person . . . within . . . insurrectionary States” unless approved by “the lawful authority.”17

Thomas Swann, chairman of the Union State Central Committee, wrote to President Lincoln expressing his apprehensions about military interference in the election, and Governor Bradford sent a letter on the same subject. Lincoln responded that he had consulted General Schenck, who had assured him that violence would almost certainly erupt on election day. The president modified Schenck’s draconian order such that only those actually engaged in violence or disruption at or near the polls would be subject to arrest, but Lincoln let the other provisions stand. Bradford issued a proclamation declaring Schenck’s order “most obnoxious and entirely without justification.” It was all the more offensive “in view of the known fact that at least two of the five provost marshals of the State are themselves candidates for important State offices.” Bradford reminded the election judges that they could “summon to their aid any of the executive officers of the county” in addition to the “whole power of the county itself to preserve order at the polls”—implicitly putting the military authorities on notice that they might be headed for confrontations with county officials. The military authorities responded by prohibiting the publication of Bradford’s proclamation in any newspaper. The governor issued his protest as a pamphlet.18

In the election campaign of 1863, the multiple factions of the Union Party divided into two camps, ostensibly on the question of slavery. The Unconditional Unionists favored immediate and uncompensated emancipation. The Conditional Unionists, led by Thomas Swann and John P. Kennedy, also came out for immediate emancipation, but in a manner “easiest for master and slave.” Masters, for example, might be compensated for their slaves, and slaves who had not yet reached adulthood might serve a period as their masters’ “apprentices.”19 The Conditional Unionists acknowledged the inevitability of emancipation, but they did not want to burden the paramount goal of restoring the Union by linking it to the abolition of slavery. They were also put off by the Lincoln administration’s use of constitutionally questionable measures to suppress dissent and by the intrusive military presence in state elections. The Unconditionals, on the other hand, professed full support for the president and his war with the South.20

Unconditional Unionists dominated the legislature elected in 1863. They approved a bill providing for a special election in April 1864, at which Maryland voters would decide whether to call a state convention to draft a new constitution, replacing the one approved in 1851. The 1851 constitution had protected slavery by prohibiting the General Assembly from “abolishing the relationship of master or slave.” The determination to overturn this restriction had helped to promote the movement for a constitutional convention.21

By 1864, however, Maryland’s defenders of slavery had little left to defend. Almost half of Maryland’s black population was already free when the war began. And slavery receded as the war proceeded, especially after 1862, when slavery was abolished in the District of Columbia, putting freedom close at hand for the large slave populations of Prince George’s County and Southern Maryland.22 Union forces contributed to the further erosion of slavery when they conscripted both slaves and free blacks as laborers. The enlistment of black soldiers exposed a complex web of interests among whites who owned slaves and those who did not. Slaves had originally been exempt from recruitment. Their exclusion raised resentments among whites who employed free black workers. Enlistment of free blacks in the army reduced their supply in the private labor market and drove their wages higher. But slave owners themselves were apprehensive about recruitment of free black men; they worried that the visible presence of black soldiers, in uniform and bearing arms, might make their slaves restless and insolent.23 A further complication was a ruling by the secretary of war that black recruits would count as “credible” against the state’s enlistment quota, thereby reducing the likelihood that white Marylanders would have to be conscripted to meet the state’s allotment of Union recruits. Unconditional Unionist Henry Winter Davis shrewdly made the case for African American recruitment by referring to the black soldier as the poor man’s substitute.24

The uncertainties that accumulated around the institution of slavery led to a collapse in the price for slaves. In 1863, an Eastern Shore newspaper estimated that slaves commanded only one-third the prices they had fetched five years earlier. In 1864, appraisers in Hagerstown assessed the value of 17 slaves at just five dollars apiece.25

RECONSTITUTION

A movement to draft a new state constitution in 1864 alarmed and reanimated the disorganized Maryland Democrats and prompted them to summon a convention of their own party, the first since the beginning of the war. They had little chance of salvaging slavery but hoped to influence how it was abandoned. Democrats were also concerned that a constitution drafted in wartime, with Unionists in power, might give permanence to restrictions and proscriptions that were chiefly disadvantageous to Democrats.26 Emancipation, after all, could have been achieved by an amendment to the state constitution of 1851. By insisting on a constitutional convention, the Unconditional Unionists hinted that they had larger objectives.

The popular vote was heavily in favor of calling a convention, especially in Baltimore, where the vote for the convention was a suspiciously lopsided 9,102 to 87. But turnout was sharply reduced in the city—only a third as large as in the presidential election of 1860. Unconditional Unionists dominated the convention’s deliberations, although Democrats managed to elect 35 of the convention’s 96 members. All of the Democrats came from the state’s southern counties with the largest slave populations, none from Baltimore.27

After addressing matters of organization and procedure, the delegates took up proposed changes in the Declaration of Rights, the statement that had preceded the body of the document since Maryland adopted its first constitution in 1776. The declaration included provisions concerning slavery and the tests of loyalty required of voters and officeholders. These issues were central to the convention’s agenda, and debate about changes in the declaration would continue, with interruptions, for two months. The proceedings were suspended so that members could attend the Republican convention in Baltimore, interrupted again during the last week of June and the first week of July so that farmers could harvest their crops, and adjourned again when General Early invaded the state.28

The Democratic minority was on the defensive from the start of the convention. Early’s raid further undermined their position, while giving the Unionists an occasion to suggest that Maryland’s southern sympathizers were somehow complicit in the attack. They argued that their Democratic opponents should compensate the state’s Union loyalists for damages suffered during the raid. The Unionists approved a resolution that all who refused to take an oath of loyalty to the United States should be held “to have taken part or openly expressed their sympathy with the recent invasion of the state” and that the federal government should send these disloyalists through the Confederate lines to the South or confine them to prison.29 The federal government ignored these pronouncements.

The committee responsible for revising the Declaration of Rights made few changes, but touched on vital issues. A new article abolishing slavery in Maryland was debated for a week. Although it was clear that the institution had no future, Democratic delegates launched a spirited defense of bondage, supported by lengthy passages from the Old Testament, which their opponents matched with quotations from the writings of founding fathers and framers of the Constitution. Much of the discussion simply echoed the longstanding national dialogue about slavery, but the debate moved into new territory when the partisans of slavery suggested that owners be compensated for the emancipation of their slaves. One proposed that slavery be abolished in Maryland on January 1, 1865, provided that the federal government appropriated $20 million to cover the losses of Marylanders whose slaves were freed. The idea was quickly rejected. Hardly anyone was confident that the federal government would approve the reimbursement. Other Democrats raised the possibility that Maryland’s government might pay for the freedom of slaves. Baltimore delegates were among the most determined opponents of this proposal because their city would have to provide much of the tax revenue needed to cover its cost, and since its residents owned few slaves, they would get little of the compensation.30

The debate on compensated emancipation ended with adoption of a near-meaningless resolution ensuring that if the federal government decided to compensate slave owners for their slaves, Maryland would see that the funds reached their intended recipients. But the state would not authorize an indefinite continuation of slavery on the uncertain likelihood that the federal government might eventually reimburse former slaveholders for their losses.31

The subject of loyalty oaths generated the most acrimonious debate of the convention, interrupting what one historian described as the “great cordiality” of deliberations notable for their “remarkable lack of personal abuse and recrimination.”32 An early portent of the later disputes arose when the convention considered a proposed article of the Declaration of Rights holding that “every citizen of this state owes paramount allegiance to the Constitution and Government of the United States, and is not bound by any law or ordinance of this state in contravention or subversion thereof.”33 This apparent renunciation of states’ rights roused the Democratic minority, who saw no necessary conflict between national authority and state sovereignty. The ensuing debate dragged on for the better part of two weeks but failed to move the majority.34

A far more serious controversy erupted after the delegates completed work on the Declaration of Rights and began to draft article I of the constitution itself, which governed the “electoral franchise.” It permanently denied the right to hold public office to anyone who had “at any time been in armed hostility to the United States . . . [or] in any manner in the service of the so-called ‘Confederate States of America.’ ” The ban extended beyond members of the Confederate government or military forces to anyone who had “given any aid, comfort, or support to those engaged in armed hostility . . . or in any manner adhered to the enemies of the United States.” The article also excluded from office anyone who had ever communicated with the rebels or expressed approval of their cause.35 The proscription was so broad that hardly anyone who stopped short of unconditional unionism could lay claim to loyal citizenship.

At first, the proscription applied only to the holding of public office. An amendment then extended its exclusions to voters. The article directed the General Assembly to approve statutes extending these restrictions to “the president, directors, trustees and agents of corporations created or authorized by the laws of this State, teachers or superintendents of the public schools, colleges or other institutions of learning; attorneys-at-law, jurors, and such other persons as the General Assembly shall from time to time prescribe.” Critics argued that the measure might deny civil rights to loyal unionists who took exception to the Lincoln administration’s deviations from the US Constitution. An amendment that would have ended the restrictions with the end of the war was defeated. Some adherents of the amendment warned that its rejection might prevent the postwar reconciliation essential to the reconstruction of national unity.36

The new constitution and the legislation carrying it into effect prescribed an oath of allegiance that election judges were required to administer to all prospective voters. Failure to do so could subject the judges to fines and imprisonment. In Baltimore, at least, the election judges needed no inducements to exclude allegedly disloyal residents from the voting rolls. Days before the presidential election of 1864, the election judges met in a local courtroom and decided that the oath was not sufficient to establish voters’ adherence to the Union. Judges were “instructed to put such other questions to voters outside of those prescribed by the Constitution as shall satisfy them that the party offering to vote is not a Rebel or a Rebel sympathizer.” A list of 25 such questions followed.37

Though the constitution’s voting provisions would not become law until it had been approved by the voters, only those voters who met the restrictions in the proposed constitution and took the oath that it prescribed would be permitted to vote. Even this exercise in anticipatory disenfranchisement failed to win overwhelming support for the document. It passed by a vote of 30,174 to 29,799. And, without the votes of Maryland soldiers on active duty with the Union Army, the constitution would have been rejected.38

Baltimore City did profit politically under the new constitution. Under the formula finally adopted, the city got three state senators (up from one) and 18 seats in the 80-member house of delegates (up from six).39

RECONSTRUCTION

The Maryland State Constitution of 1864 backfired on its framers. Instead of solidifying the rule of the Unconditional Unionists, its “registry law” angered and eventually mobilized the state’s dormant Democrats, while exposing breaks in the ranks of the Unionists themselves. Congressman Henry Winter Davis had emerged as the voice of the Unconditional Unionists. He squared off against Conservative Unionist Montgomery Blair, postmaster general in President Lincoln’s cabinet and a leader in state politics. Both supported emancipation, but they disagreed on how to achieve it and what would follow. Blair wanted slave owners compensated for their slaves, opposed the recruitment of black soldiers for the Union army, and recommended that free blacks be required to emigrate to Haiti or elsewhere. Davis and the Unconditionals disagreed with Blair on all three issues and advocated racial equality. As postmaster general, however, Blair controlled 500 patronage jobs in Maryland, and Davis’s political career ended with his death in 1865. Blair became principal leader of the Unionists and continued his effort to strengthen the new political organization by appealing to Democrats and former Democrats.40

By war’s end, however, Blair’s leverage with Democrats was evaporating. The new state constitution of 1864 freed the slaves and all but ruled out the compensation that Blair sought for their owners. The equal protection guarantees of the Fourteenth Amendment to the US Constitution pushed even more white voters away from the Unionists and into the ranks of the Democrats. When national Republican leaders expressed support for the enfranchisement of African Americans, they prompted still another wave of defections from Blair’s Conservative Union Party to Maryland’s more rigorously racist Democrats.41

The constitution of 1864 and its registry law sustained a politically artificial and ultimately untenable Unionist regime. The Civil War had helped to hold the Unionists together. Once the war was done, so were the Unionists.42 Baltimore’s election results showed the extent to which Unionist rule depended on manipulation of the electoral process. In 1860, Abraham Lincoln finished last of the four presidential candidates in Baltimore, with 3.6 percent of the city vote. Four years later, he carried Baltimore with nearly 84 percent of the city vote. The difference, as the Sun remarked, reflected not so much a mass conversion of Democrats into Republicans as a 40 percent drop in voter turnout between 1860 and 1864.43

A shadow electorate waited on the political sidelines, having been turned away from the polls, or unwilling to expose themselves to the oaths and interrogations of election judges and registrars. Other potential voters soon appeared. Approximately 20,000 Confederate Army survivors were returning home to Maryland. The first of them—paroled prisoners of war—happened to appear in Baltimore at the time of President Lincoln’s assassination. Some Unionists feared that the ex-Confederates planned to redeem their military defeat with a campaign of political murder. Local military officials imposed martial law on the city, but only for a day. The Confederate veterans were instructed to report to the provost marshal and forbidden to wear their old uniforms. Their presence hardened the determination of the Unconditional Unionists, now called the Radicals, to defend the registry law. It would permanently bar southern soldiers and southern sympathizers from becoming voters.44

Unionist measures to exclude their opponents from the voting rolls became more severe. The names of all adult white males were entered in the registration books, so that even those who had not attempted to vote could be challenged if they presented themselves at the polls. The failure to vote was now reason for suspicion, a sign of a voter’s reluctance to face the election judges and their questions. The electorate continued to shrink. Unionist candidates won the legislative elections of November 1865. But in Baltimore, only 10,842 registered voters remained on the rolls, and almost half of these did not vote. Little more than two months later, a petition protesting the registry law arrived in Annapolis from Baltimore. It carried 11,274 signatures.45

Baltimoreans had struggled to insulate their city from the country’s deadly division over slavery. But the conflict took possession of the town. Baltimore was occupied by federal troops, its elected government was displaced, its officials were imprisoned, and a purged electorate imposed an alien political regime on the city.