DEMOCRATIC RESURRECTION

BY 1866, THE ATTENUATED ELECTORATE IN MARYLAND must have included few voters who were not Unionists, but they were divided between Conservative Unionists and Radical Unionists. The situation presented the Conservatives with an obvious opportunity to depose their Radical rivals. The Conservatives could reach out to the thousands of would-be Democratic voters who had been exiled from the electorate or had withdrawn from it. These potential voters were sharply at odds with the Radicals but had much in common with the Conservative Unionists.

Thomas Swann, formerly Baltimore’s Know-Nothing mayor and now the state’s ostensibly Unionist governor, recognizing that the Unionist coalition was split and sinking, denounced the Radicals and redirected state patronage to Democrats. He fired Unionist election judges and instructed their replacements (often Democrats) to interpret the registry law as liberally as possible, opening the rolls to voters previously excluded. In Baltimore, the Radicals who ran the municipality faced an election in October 1866. With the support of the city solicitor and the state attorney general, they held that the new voter lists created under Swann’s direction were invalid and that the only legal registration rolls were those used in the election of 1865. Though challenged by Democratic attorneys, the election went forward under the Radicals’ ground rules. They won every office in town. But fewer than 8,000 citizens turned out to vote. In 1860, more than 27,000 citizens had voted in the city’s mayoral election.1

The state and congressional elections of 1866 followed closely on October’s municipal contest. The Conservatives would have to act quickly to prevent another Radical sweep in Baltimore. Less than a week after the municipal election, a “Conservative City Convention” met in Baltimore, alleging misconduct by the board of police commissioners—especially its refusal to appoint any Democrats as election officials. The convention urged Governor Swann to put the commissioners on trial, as he was entitled to do under state law. The convention’s resolutions reached Swann along with a petition signed by 4,300 Baltimoreans demanding that the police commissioners be dismissed. Swann issued a summons demanding that the commissioners appear before him for trial. They sent their attorneys instead.2

Two days after the Conservative City Convention, the Radical (formerly Unconditional) Unionists assembled to protest Swann’s interference in Baltimore’s electoral arrangements and to proclaim the formation of a new organization—the “Boys in Blue”—consisting entirely of Union Army veterans. The men were summoned “to assemble in massed column to resist the attempt of the traitors in our midst to deprive the loyal men of our city of the control of our affairs and to hand them over to the tender mercies of our deadliest enemies.”3

The new organization hinted at something more forceful in the way of electoral politics than oaths of allegiance, perhaps a reversion to the violence of the Know-Nothing era. The state had no militia to mobilize against such threats—a lingering consequence of federal occupation—and Radicals still controlled the local police force. Governor Swann turned to President Andrew Johnson, who had already been in touch with Maryland’s aggrieved Democrats. The Marylanders wanted presidential support in their battle with their Republican antagonists; Johnson wanted Maryland’s support for his reconstruction policy.4

Early in 1866, Maryland’s Democrats and Conservative Unionists jointly sponsored a rally at the Maryland Institute in Baltimore to declare their support for the president’s reconstruction policy. By summer, the alliance of Unionists and Democrats had become a single party under the Democratic Conservative label. Days after the pro-Johnson rally, the Radical Unionists sponsored a counter-rally at the Front Street Theatre to announce their opposition to presidential reconstruction. By some accounts, the meeting marked the birth of the state’s Republican Party.5

The nascent parties, already at odds with one another on race, slavery, and the right to vote, now resolved to disagree about national reconstruction as well. Johnson responded to Governor Swann’s request for support by instructing General Ulysses S. Grant to “look into the nature of threatened difficulties in Baltimore.” Grant, the Army’s commanding general, ordered General Edward Canby, commander of the military department that included Maryland, to visit Baltimore. Canby reported that there was no danger of riot in the city unless Governor Swann dismissed the Radical police commissioners and replaced them with his own appointees. Grant consulted with Swann, who seems to have agreed with this assessment. A week later, however, Swann completed the trial of the Baltimore police commissioners, found them guilty of malfeasance and misconduct in office, and dismissed them. On the following day, he appointed William Thomas Valiant and James Young to replace the Radical commissioners, deliberately creating the very conditions that Grant and Canby saw as the formula for civil disorder. With the assistance of the local sheriff, Young and Valiant attempted, unsuccessfully, to occupy the offices of the police commissioners. But there was no riot. Instead, on November 3, the Radical Unionist judge of Baltimore’s criminal court, Hugh Lennox Bond, issued a warrant for the arrest of Young and Valiant.6

Young and Valiant refused to post bail and landed in the city jail. A team of attorneys, including John H. B. Latrobe, applied to the Maryland State Court of Appeals for a writ of habeas corpus to set them free. The writ was granted, but under state law the warden of the city jail could delay their release for four days so that the respondents would have the opportunity to contest the writ. The release of the new police commissioners was therefore postponed until after the election. Grant and Canby arrived in Baltimore for discussions with the Republicans, who remained in control of the city’s electoral apparatus. Canby reported that the Republican officials had agreed to appoint one Democratic election judge and one clerk in each of the city’s precincts. A list of proposed judges and clerks had already been prepared by the Democratic Conservatives, but when it was delivered to the office of the police commissioners, their attorney declined to receive it. Through a half-opened door he announced that the judges and clerks had been appointed, and no changes would be made.7

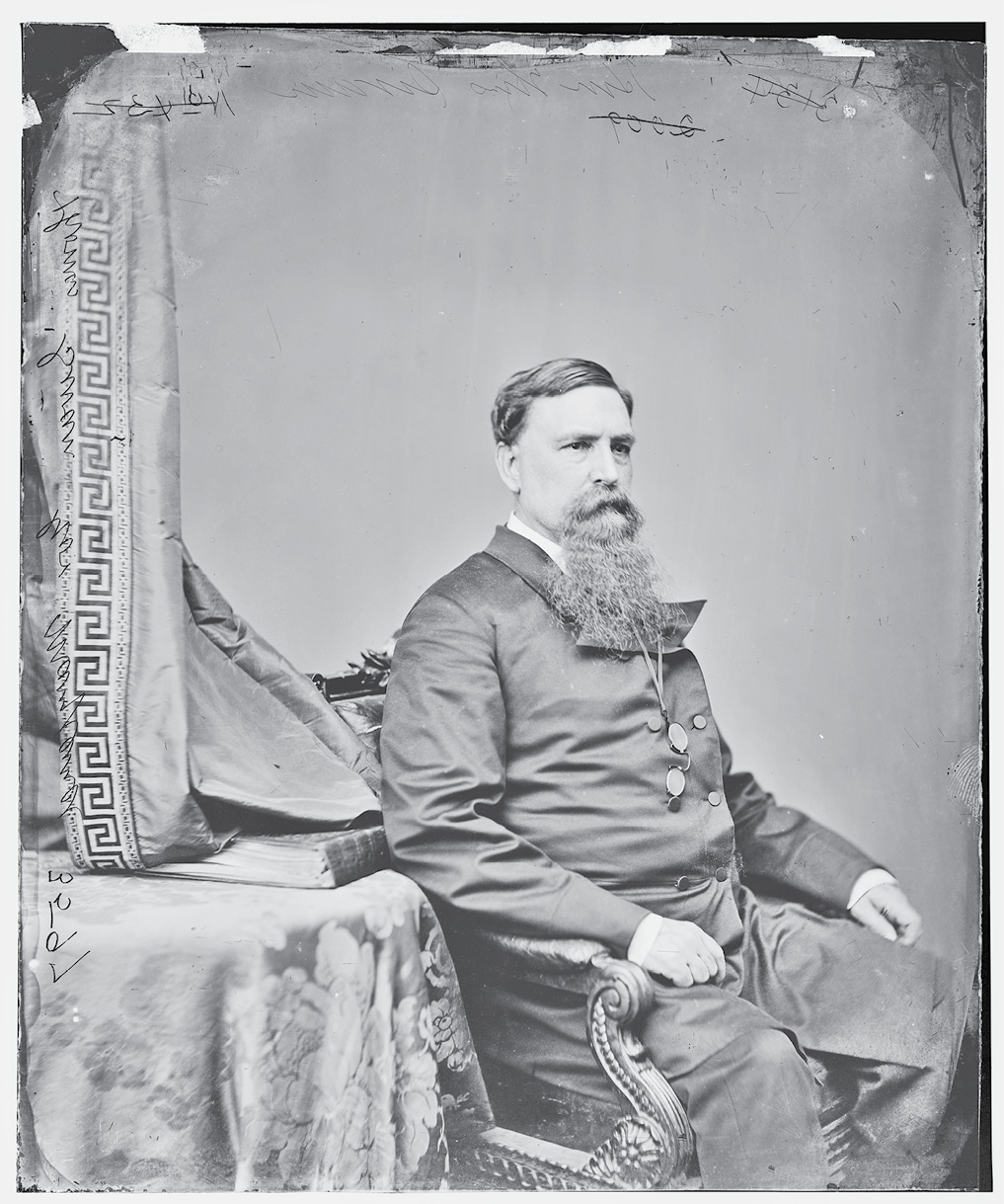

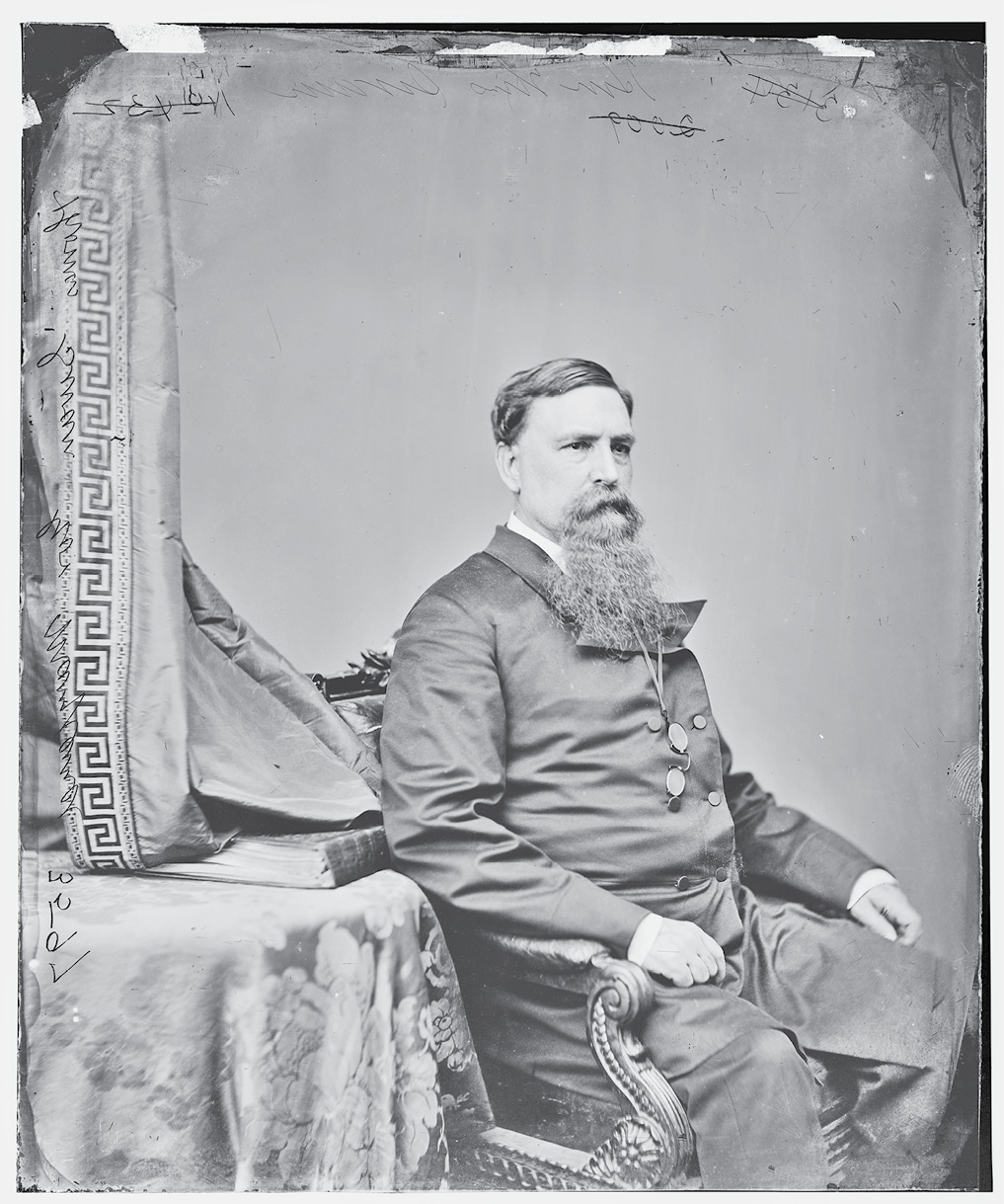

Thomas Swann, president of the B&O, mayor, governor, and almost US senator; Whig, Know-Nothing, Unionist, and Democrat

Though the Republicans had not been dislodged from their oversight of Baltimore elections, the results of the state and congressional contests of 1866 ran powerfully in favor of the city’s Democrats. They had acquired the courage to vote and had presented themselves at the polls in such numbers that the Republican election judges and registrars may have feared that turning away so many aspiring voters might provoke a riot. A. Leo Knott, secretary of the Democratic State Central Committee, maintained that the Democratic Conservatives were moved to brave the perils of the polls because they were outraged by the Republicans’ “contemplated crime against the electoral franchise and the rights of citizens deliberately planned by the Republican party and aided by Judge Bond.” But they may also have been emboldened by the challenge that Governor Swann posed to the Boys in Blue and their Republican backers. Two weeks before the election, the governor issued a proclamation warning them that their “illegal and revolutionary combinations against the peace and dignity of the State” would be “held to strict accountability in the event of riot and bloodshed.”8 In effect, Swann’s proclamation converted the Radical Unionists into rebels, and his condemnation, together with his dismissal of the Radical police commissioners, provided a context of legitimacy for Democratic Conservative voters and the encouragement of official support. In the background, there was also the possibility that President Johnson might order federal troops to add steel to Swann’s threats.9

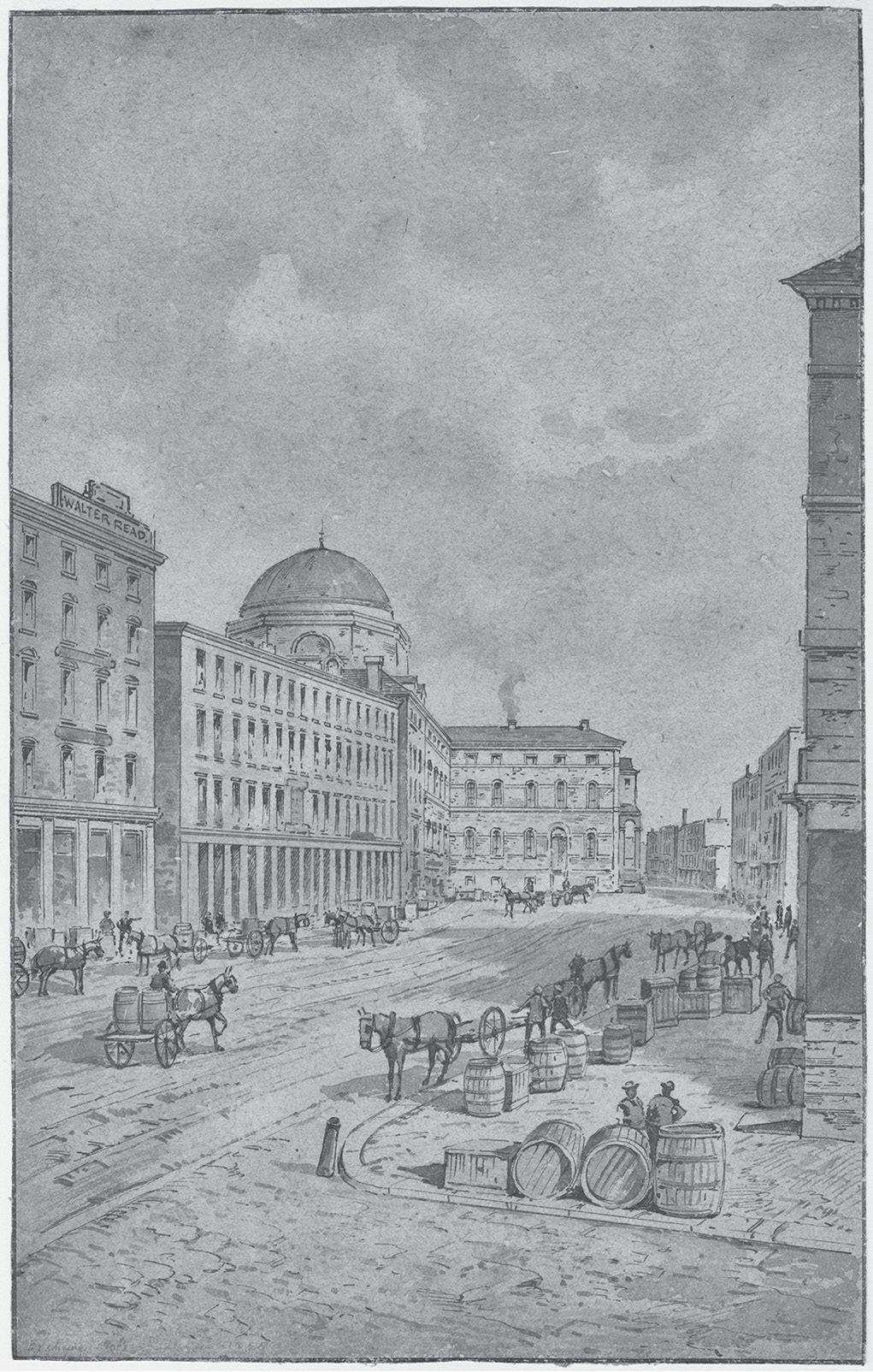

On the morning of November 8, two days after the election, Swann was walking from his home on Franklin Street to his nongovernmental job as president of the First National Bank on Gay Street. By the time he reached Baltimore Street, he was surrounded by a sea of Baltimoreans who greeted him with “hearty cheers.” Those who could get close enough reached out “to shake him cordially by the hand.” The crowd grew so dense that the governor could make scarcely any progress toward his office. The mass of Baltimoreans propelled him toward the Merchants’ Exchange, where he tried to escape by entering the building, with the hope that he might retreat either to the adjacent customhouse or the post office, at opposite ends of the building, and make his escape. But the crowd filled the exchange’s rotunda and cut off his exits. Swann mounted a stairway to address them. Though it seemed unnecessary, given the celebratory spirit of his audience, Swann offered a detailed justification for his dismissal of the Radical police commissioners. But he emphasized, above all, the dignity, courage, and law-abidingness of Baltimore’s Democratic voters in the face of Radical provocation.10

That night, a band marched to Swann’s home to serenade him. He eventually emerged to deliver another version of the speech he had made earlier in the day.11 The gratitude of Baltimore’s Democrats was due in part to the most recent transformation in his political identity—having changed from Whig to Know-Nothing, then to Unionist, then, in May 1866, to Democrat. His electoral exertions had given the Democrats a two-thirds majority in the house of delegates, for which he expected something more than serenades and ovations. It had been understood that his newly adopted party’s legislators would elect him to the US Senate, which they did.12

After more than a decade in purgatory, Baltimore’s Democrats were back in control of their state, but not the US Senate. Thomas Swann’s enemies were determined to deny him the seat bestowed by Maryland’s Democratic legislature. A suspected plotter in the affair was Lieutenant Governor Dr. Christopher Columbus Cox, who was, like Swann a political nomad, but one who had finally come to rest with Maryland’s Republicans. The office that he held had been created under the state constitution of 1864. Swann’s elevation to the US Senate would make Cox governor. The Senate’s refusal to seat Swann would give Cox the opportunity to appoint his own candidate to that Senate seat. Cox, according to rumor, would then do what he could to block the movement for a new constitutional convention to undo the Unconditional Unionist constitution of 1864, and if he failed, there was the possibility that federal troops would be sent to the state to ensure that loyalists were in command of its government. As the scheme unfolded, Cox stoutly denied any responsibility for engineering it. And he may have been telling the truth. Maryland’s Republicans generally detested Swann as a traitorous Unionist turned Democrat. Any of them might have conspired with the Republican majority of the US Senate to keep Swann from occupying his seat there.13

Exchange Place, ca. 1855. The Merchants’ Exchange, in the background, was designed by Benjamin Latrobe and completed in 1820; it was demolished in the early twentieth century. At various times it housed a US customhouse, a stock exchange, a bank, and a post office. It frequently served as the site for public meetings to discuss municipal problems. Courtesy Enoch Pratt Free Library, Cator Collection

For the Republicans, spite had trumped political sensibility. Swann inevitably got wind of the scheme and announced that instead of trying to occupy his Senate seat, he would remain governor in Annapolis, where he could do far more damage to Maryland’s Republicans than he could as a US senator. The two police commissioners whom he had appointed were out of jail and in charge of Baltimore’s police officers. In his message to the General Assembly at the start of its 1867 session, Swann recommended that the legislators consider holding a new municipal election in Baltimore to correct the “flagrant injustice” of the one held the previous October. He also urged the formation of a new state militia, which would give the state’s Democratic government the muscle needed to counter Republican threats. Finally, Swann asked the assembly to summon a new convention to replace the constitution imposed on the state just three years earlier.14

The General Assembly soon approved a bill restoring voting rights to those who had lost them under the Radicals’ registry law. It also approved legislation requiring a new municipal election in Baltimore, to be held just 16 days after the bill passed. Baltimore’s Democrats needed only four days to assemble a nominating convention to select its candidates for municipal office. Robert T. Banks, a glass and crockery merchant who had never held elective office, led the ticket as the Democratic Conservative candidate for mayor. He was a native Virginian with Democratic attachments and southern sympathies.15

A LITTLE CIVIL WAR

Baltimore’s Republican city council unanimously approved a $20,000 appropriation to litigate its way out of the new municipal election. The money was to pay attorneys “to test the validity of the action of the General Assembly, in their recent legislation, for the removal of the existing city government.” Mobilizing lawyers of their own, Baltimore’s Democrats secured an injunction to prevent expenditure of the $20,000.16

Disputes concerning Baltimore’s new municipal election erupted next within the Democratic Conservative coalition in Annapolis. The Conservative Unionists had restored the voting rights of Democrats in order to defeat their Radical Unionist rivals. When Democrat Robert Banks defeated a Conservative Unionist candidate to win the mayoral nomination in Baltimore, Conservatives discovered that even in a city where Conservative Unionists seemed strong, their new Democratic allies were stronger. Conservatives did not intend to become junior partners in the alliance. Conservative Unionists still exercised sufficient control in the General Assembly to derail the new municipal election in Baltimore, and Conservative Unionists in the state senate could also deny the two-thirds majority needed to call a constitutional convention. The convention bill had been introduced early in the session and called up twice, but its consideration was suspended on both occasions when the necessary majority failed to materialize. The assembly’s Democrats chose, for the moment at least, to sacrifice the special election in Baltimore City in return for Conservative Unionist support on the constitutional convention (which could once again address the political status of Baltimore). The state senate repealed the municipal election bill, which had not yet been signed by Governor Swann, and two-thirds of the legislators voted for a referendum on a new constitutional convention.17

Maryland voters went to the polls in April 1867 to vote for the convention and to choose delegates. The Republicans, who rejected the exercise as unconstitutional, nominated no delegates. Since the start of the year, they had pursued a radical line of attack against the state’s government. Their goal was to persuade the Republican majority in the US Congress to assume authority over Maryland, either because the state did not have a republican form of government, as required by the US Constitution, or because it was governed by disloyalists and, like the former Confederacy, was in need of federal reconstruction.18

The document that emerged from the constitutional convention contained few surprises. As expected, it did away with the test oath and the proscriptions that barred so many Democrats from becoming voters, but it retained one of the most significant innovations of 1864: creation of a statewide system of public education, overseen by a state board of education and financed, in part, by state taxation. Under the 1867 constitution, representation in the General Assembly was to be based on total population, not just white population as prescribed by the constitution of 1864. The change benefited the state’s southern counties—home to a significant population of ex-slaves. Southern Maryland gained seven delegates when nonvoting African Americans were counted as part of the population to be represented. The new constitution also created a new county, Wicomico, on the Eastern Shore to accommodate the town of Salisbury, which until then had been divided between two counties. The addition of Wicomico gave the southern counties a majority in the state senate, even though they accounted for less than a third of the state’s population.

In the matter of race, the constitution made one departure that might not have been expected of its Conservative authors: it opened the courts to black witnesses. But the delegates made it clear that this concession to racial equality was not a step toward general equality. African Americans might have civil rights, but they were not the political equals of white men.19

Article XI of the new constitution was devoted to the governance of Baltimore. It was brief. Baltimore would elect a new municipal government in October 1867. In this respect, the city’s elected officials faced the same prospect as state officeholders in general, all of whom would step down after ratification of the constitution—except Governor Swann, who would serve out the remainder of his term. The only significant change in the powers of city government reduced its authority to incur debt to pay for internal improvements. It would be able to finance projects such as railroads and canals only with the approval of the General Assembly, followed by the approval of city voters. The restrictions could not have aroused much opposition among Baltimoreans. The city’s investments in internal improvements had yielded disappointing returns, and its relationships with railroads in particular had passed from distant to acrimonious.20 The B&O, Baltimore’s great civic venture in the conquest of distance, had transformed itself into an aggressively private corporation.

CITY AT PEACE

For Baltimore’s government, peace brought new stresses. Prices had risen sharply since the beginning of the war, and one class of city employees after another demanded pay increases consistent with the higher cost of living. Most got raises.21 Similar demands unsettled the private sector. B&O machinists went on strike to demand higher pay for overtime work. The city council instructed its representatives on the railroad’s board of directors to look into the sources of the work stoppage and possible ways of ending it. And the council went further. The first branch took the side of the machinists and supported their wage demands. The second branch tabled the resolution.22 The intractable labor-management dispute was an early sign of more severe conflict to come between railroad workers and railroad capitalists. The intervention by the council’s first branch anticipated the politicization of these struggles.

The city’s longstanding engagement with railroads continued—and continued to be a source of trouble. In 1865, for example, the B&O raised its rates for the shipment of coal. Coal was Baltimore’s staff of life. It powered the steam engines that animated the city’s industries. The city council passed a resolution of protest holding that the increase was unjustifiable and asked the city’s representatives on the B&O board to report. All of the council’s representatives on the board had opposed the increase, but neither their protests nor those of their colleagues diverted the B&O from its new rate schedule.23

The municipality’s relations with the Northern Central Railway had degenerated into lawsuits and injunctions. The city had objected to the proposed route of the railroad’s extension to the waterfront in Canton and then complained about the company’s failure to complete the line on schedule. In laying its tracks through other parts of the city, the Northern Central had illegally changed the grades of city streets, rousing the anger of local property owners and their council representatives. City officials also charged that the Northern Central had failed to meet its financial obligations to Baltimore. They were also unhappy that the railroad had moved its headquarters from Baltimore to Harrisburg. The city council ordered the Commission on Finance to sell the city’s entire stake in the Northern Central for not less than $800,000. The city’s interest in the company was reported to be worth $1 million.24

The city had no investment in the Philadelphia, Wilmington, and Baltimore Railroad, but the company managed to antagonize municipal leaders in the worst possible way—by contributing to Baltimore’s urban inferiority complex. The PW&B had repeatedly sought permission to lay a double track along Boston Street to its President Street Station. The double track would leave scarcely any room for other street traffic. In 1865, the railroad renewed its request. This time it claimed that it was building a straight-as-the-crow-flies line from Washington to New York—the so-called Air Line Railroad. If Baltimore refused to allow a double track on Boston Street, the PW&B would have to bypass the city, leaving it disconnected from the most efficient route linking the biggest cities of the northeast corridor. The city needed the railroad, in other words, but the railroad and the big cities it served could do without Baltimore. Mayor John Lee Chapman found the railroad’s position dishonest and insulting. He noted that the PW&B had not asked Philadelphia to allow double tracks through its streets but had taken a detour around the city. It appeared, moreover, that the Air Line Railroad was little more than air. “The Baltimore Representatives of this Company,” wrote Mayor Chapman, “seem to be blind to all interest[s] but those of Stockholders, and have concluded that Baltimore is a Country Town.” Chapman’s hostility was not limited to the PW&B. He took “a determined position . . . in opposition to the continued efforts of Railroad Corporations to take every advantage” of Baltimore and its citizens.25 Railroads, once seen as Baltimore’s salvation, were now regarded as predators.

Baltimoreans found new sources of disagreement among themselves. Their differences on questions of race and secession persisted, but they had dropped beneath the surface of local politics after Appomattox and left room on the local political agenda for debates about less weighty issues. One of the most controversial questions in the years just after the war was whether to renumber the city’s houses. Mayor Chapman, in his annual message for 1867, explained that since the city had last assigned street addresses, a large population of new buildings had sprung up to complicate the numbering system. Strangers and residents alike were often unable to find their way around. Worse yet, the confusion complicated the work of city officers and tax collectors.26

Competing petitions for and against renumbering carried the names of hundreds of citizens and business firms.27 The volume of popular expression seemed to paralyze the city council. The committee assigned to report on renumbering was unable to reach consensus. It submitted a majority report in favor of renumbering and a minority report against. The council’s second branch “indefinitely postponed” consideration of the first and rejected the second.28

CITY HALL: URBAN STATUS SYMBOL

While the renumbering exercise stalled, Baltimore’s long-delayed drive to get its own city hall finally moved forward. The municipality had never had a purpose-built city hall to house its public officials and solidify its fragile sense of civic pride. For several decades, the city council held its sessions in a former museum. Founded by Rembrandt Peale in 1814, the museum had once held an eccentric collection of portraits, fossils, and animal specimens. Peale was unable to make the museum a going concern, and the city purchased it in 1830. The first branch met in a former picture gallery; the chamber occupied by the second branch had previously held stuffed dead animals.29

Before the Civil War interrupted the project, the General Assembly had authorized the city to issue up to $400,000 in stock to build a city hall. A special committee of the city council selected a site on Holliday Street not far from the Peale Museum, but nothing happened until 1860, when Mayor Swann announced that the municipality had leased the property. Under an ordinance approved by the council, Swann appointed commissioners to select a plan for the building. They did so, and the council authorized the appointment of another commission to oversee construction. The second commission reported that the plan chosen by the first commission would cost much more than the city could spend. On the recommendation of Mayor Swann’s successor, George William Brown, the council postponed further work on the building because the city could not afford it.30

During this postponement, city officials made do with the buildings that already stood on the intended site of their imagined building. The mayor’s office was in the back parlor of “an old-fashioned private residence.” His secretary occupied the front parlor, which also served as a waiting room for contractors, politicians, and job seekers who wanted to meet with the mayor. The city’s tax appeal court held its sessions in a chamber measuring 12 by 15 feet, and some of the tax collector’s clerks labored in sheds and outbuildings.31

Mayor Chapman restarted the city hall project with his annual message in 1864. The city council appointed a new commission to select a new architect for the building. It chose the design of George A. Frederick, an unknown in his early twenties embarking on his first independent project since completing his apprenticeship. The land once leased for the building was now purchased. Chapman and the council approved an ordinance appointing a new building committee to oversee completion of the work, and once again asked state approval to sell the bonds needed to pay for the project. This time the General Assembly authorized Baltimore to issue $600,000 in bonds. As required by the state constitution of 1867, Baltimore’s voters approved the sale of the bonds by referendum, and construction began almost immediately—more than a dozen years after the city council first sought the assembly’s approval for the building.32

The laying of the cornerstone occurred just after the municipal election of 1867. Only a small part of the building was finished in time for the ceremony—barely enough to support a cornerstone. Mayor Chapman attended, but he had just been voted out of office. The Sun suggested that his administration’s unrepresentative, lame-duck status had been essential to the advancement of the long-delayed city hall project: “it required such temerity as only an expiring administration could summon to initiate the work just now, especially on so stupendous a scale as has been projected.”33

John H. B. Latrobe served as orator for the cornerstone ceremony. His speech reviewed the city’s history, perhaps to demonstrate why it deserved a city hall and why the improvised arrangements for housing Baltimore’s government were “unbecoming to the character of our people.” He closed by recounting the achievements of its recent mayors. Most were the accomplishments of Thomas Swann. Latrobe mentioned Chapman’s expansion of the city’s water supply but gave him no credit for restarting the construction of city hall.34

It proved to be a false start. Chapman’s Democratic successor, Mayor Robert T. Banks, challenged the authority of the building committee, largely because he was not one of its members. According to Banks, the building committee operated in violation of the law, which required the mayor, register, and comptroller to open bids and determine the amount of the bond that contractors were supposed to post as security for fulfillment of their contracts. Worse yet, the cost of the “latitudinarian” contracts already signed by the building committee far exceeded the amount the General Assembly had authorized for the project. The members of the building committee rejected the mayor’s demand that they resign, but they agreed to stop all work on city hall until the courts ruled on their legitimacy and their contracts.35

The city’s superior court decided in favor of the building committee. Mayor Banks prevailed in the Maryland Court of Appeals, which found that the state legislation authorizing Baltimore to issue bonds for city hall was insufficiently explicit about the committee’s authority to make contracts with suppliers and builders, all of which were declared invalid.36

Eighty years after it became a city, Baltimore finally built a city hall.

The decision had no effect. Two months before the appeals court announced its decision, the General Assembly empowered the city to issue as much as $1 million in bonds to pay for its city hall. With the approval of the voters, the city council approved a new bond issue and appointed a new building committee—chaired by Mayor Banks.37

Less than a year later, the city council formed a special committee to investigate charges of fraud in the operations of the new building committee. After completing its inquiry, the committee submitted a resolution demanding the resignation of the building committee. All of the contracts it had made were to be annulled, and the city register was to make no further payments for the construction of city hall until instructed to do so.38

Baltimoreans who bothered to read the committee’s report to the very end learned that it had found no evidence of fraud. No one on the building committee had “any interests in any contracts awarded by them.” The special committee concluded instead that the building committee had made errors in judgment, perhaps a result of a “too great reliance on the representations and opinions of others, and want of proper knowledge or experience to discharge properly the duties of their respective positions.” To avoid such errors in the future, the building committee would have to include three “practical mechanics.” Mayor Banks and his associates on the committee offered a lengthy response and had it printed as a 38-page pamphlet for public consumption. They acknowledged that they had occasionally decided not to award contracts to the lowest bidders, because they did not regard the low bids as “responsible.” In a contract for brick work, for example, the committee had passed over the lowest bidder to give the job to the mayor’s brother-in-law. They also rejected the low bid in a contract for lumber, which went to a firm in which the mayor’s brother was a partner. The lowest bidder for excavating the city hall cellar was L. D. Gill, but another contractor got the job. N. Rufus Gill chaired the investigating committee.39

Chairman Gill delivered his committee’s response to Mayor Banks’s statement, emphasizing that the issue was not one of corruption. The investigators saw nothing improper, for example, in awarding the lumber contract to the firm in which the mayor’s brother was a partner. Their complaint was that the lumber had been of substandard quality and ordered so far in advance of its use that the building committee incurred additional expense for its storage.40

The council passed an ordinance that embodied the recommendations of its investigating committee, including the requirement that Banks’s committee resign.41 Banks rejected it. His remarkable veto message came out in another printed pamphlet, an indictment of the council’s committee of investigation as the “offspring of those seasons of public excitement which have produced so many monstrous things in the history of our city.” The inquiry, Banks insisted, belonged to the same family of “monstrous things” as the Bank Riot of 1835 and the deadly violence of the Know-Nothing movement—animated by rumors of conspiracy, much like the rumors of corruption in the city hall building committee. In short, the mayor and his committee were victims of Baltimore’s mob politics.42

Banks portrayed himself as a public official whose conscientious decisions to veto previous ordinances had set the council against him: “Indignant that he should thus stand in the way of their sovereign will and pleasure . . . determined to strip him of his prerogatives, as well as to crush and humble him at the foot-stool of their power. Indeed the two Branches of the Council have treated the Mayor of Baltimore not otherwise than Andrew Johnson was treated by the two Branches of Congress. This determination on the part of the Council to crush him and humble him in the dust, has culminated at last and reached its climax, in the ordinance . . . now under consideration.”43

The council declared that Banks’s veto was invalid because it was printed and did not carry his signature, but it took the additional precaution of overriding it. Banks contested the council’s action but could not prevent its approval of a new ordinance for the construction of city hall and its appointment of a new building committee. The committee elected as its president Joshua Vansant, a local hat maker who served as chairman of the Democratic Conservative State Central Committee. Vansant reported that Mayor Banks refused to administer the required oaths of office to the members of his committee.44

The mayor and his building committee finally surrendered. The new building committee took office and restarted construction on city hall. In March 1870, however, Vansant reported that the $1 million authorized by the General Assembly would be exhausted by the end of the year, and while he could not precisely calculate the additional money needed, he supposed that it might amount to another $1 million. In the end, the building’s total cost would come to about $2.5 million, with another $110,000 for furnishings. Though the city council began to hold sessions in its new chambers in April 1875, the building would not be completed and dedicated until the following October. The Sun ventured the hope that the council members would live up to the grandeur of their new chambers.45