POLITICAL ECONOMY

ISAAC FREEMAN RASIN’S DEMOCRATIC ORGANIZATION suffered decline along with Baltimore’s factories, unions, and railroads. Its manipulation of the city’s electoral system may have revealed its essential weakness: it might not have relied so much on stealing elections if it had been able to win them legitimately. The need for Freeman Rasin to “perfume” the machine’s ticket by surrendering offices to reformers and other political innocents was another sign that Baltimore’s boss was no Boss Tweed, and the uncertain loyalty of ward leaders such as J. Frank Morrison and Robert J. Slater was further evidence of his organization’s weakness.

In other cities, immigrants and first-generation Americans provided reliable votes for machine politicians. But in 1890, Baltimore’s foreign-born population, at 15.9 percent, was the smallest among the country’s 10 most populous cities.1 Rasin’s organization also lacked the resources needed to win support of immigrants or anybody else. Toward the end of his political career, Rasin was still wondering how to win over the city’s foreigners. He posed the problem to a visiting Tammany notable from New York City, Congressman Timothy “Silver Dollar” Sullivan, who stopped by for a visit on his way home from Washington. “You see,” said Sullivan, “we have means of taking care of them in New York that perhaps you haven’t got here. Of course, there’s an awful lot of them, particularly Italians, but I guess we have more patronage in my Assembly district than you have in your whole city.”2

The infirmities of the Baltimore Democratic organization arose not only from the city’s limited electoral base of foreign-born voters but from its limited supply of tangible rewards to solidify their political support. The same commitment to “internal improvements” that burdened the city with debt also restricted its ability to generate patronage.

In other cities, alliances with the local business community may have been just as important to the emergence of political machines as the votes of ethnic groups. In a classic essay, Martin Shefter shows how the consolidation of the Tammany organization in New York depended on an alliance of Boss “Honest John” Kelly with a coalition of corporate lawyers and managers—the “swallowtail” faction of the Democratic Party, named for their fancy dress coats. They were the representatives of “mature” capitalism, not speculators or robber barons but solid corporate owners and managers who shared Kelly’s interest in the order, predictability, and centralization of urban politics. Like Kelly, Rasin relied on businessmen to give his organization substance and respectability. Eventually, he would depend on committees of businessmen to sponsor the organization’s candidates, while the boss himself stood on the sidelines pretending to be an uninvolved spectator.3

Baltimore’s “branch-office” businessmen, of course, were hardly the hefty moguls that backed up machines in New York City, Chicago, and Pittsburgh. Strained relations between the Rasin-Gorman Ring and the B&O Railroad precluded a strong alliance between Baltimore’s bosses and its most prominent business enterprise. Tension between the railroad and the Ring erupted into open hostility during the reformers’ crusade for the “Australian ballot”—a standard ballot printed by the municipality, not by the parties, and cast in secret. The battle was condensed and personalized in the white-hot animosity between Arthur Gorman and John Cowen of the B&O. In the 1889 campaign for the Australian ballot, Gorman ignored all of his reform opponents except Cowen. In a vigorous stump speech, he accused Cowen of using the reform movement as a vehicle to advance the corporate interests of the B&O. Cowen responded with a four-column letter in the Baltimore Sun; Gorman’s response provoked another letter. Finally, days before the election, Cowen produced a masterful piece of political theater. At the climax of a speech before a mass audience, he introduced two minions of the machine who had defected, and he carried the pair through a catalog of electoral crimes they had committed on behalf of Gorman and Rasin.4

Rasin’s candidates carried the city as usual, but the struggle against the machine continued, and the fight over electoral reform became even more closely entwined in the personal feud between Gorman and Cowen. Gorman denounced the Australian ballot as a weapon to destroy the Democratic Party and empower its traitorous Independents, “selfish men, identified with corporate greed.” The reform movement, he insisted, was “a corrupt scheme of Mr. Cowen’s to get possession of the Legislature in the interest of the B&O R.R. Company, and to prevent its tax exemptions from being interfered with.”5

Freeman Rasin’s organization became the first casualty of the feud between Gorman and Cowen. Its collapse began with an attempt at reconciliation. In 1892, Gorman’s second term in the US Senate would end, and he wanted to be elected to a third, but his ongoing feud with Cowen cast a shadow over his prospects. He turned to a colleague in the Senate who, like Cowen, was a railroad executive. Gorman asked him to approach Cowen with an offer of truce. Cowen agreed to end his attacks on Gorman so long as Gorman and his allies in Annapolis and Washington looked kindly on the interests of his railroad.6

Rasin was not covered by the treaty between Gorman and Cowen. He achieved a similar peace, however, by surrendering much of the Baltimore City Democratic ticket to the Independents. They predominated among his organization’s nominees for the General Assembly, and while organization candidates were slated for most municipal offices, Independents were sponsored by Rasin for the city’s judiciary—the Supreme Bench. His strategy virtually silenced charges of bossism in the city elections of 1893.7

The peace was brief. In 1894, the US Senate was considering a measure that would legalize railroad “pooling,” an anticompetitive practice under which ostensibly competing lines divided their total earnings according to an agreement specifying the proportion each road should receive. The B&O belonged to a pool that covered railroads in the Northeast, and John Cowen, with the assistance of Rasin, was one of the lobbyists who succeeded in persuading the House of Representatives to pass this controversial bill. When the legislation was to come up for a vote in the Senate, Senator Gorman, chairman of the Democratic Caucus, argued that other pieces of legislation essential to the operation of the federal government should be considered before the railroad bill and, later, that there was insufficient time to consider the pooling bill before the close of the session. Cowen regarded Gorman’s conduct as a violation of their truce and prepared for an all-out showdown with the Ring during the municipal election of 1895.8

Gorman had withstood such attacks in the past, but he undermined his support among regular Democrats in Maryland by breaking with President Cleveland on the issues of silver coinage and the tariff. As a Senate leader, Gorman practiced the art of compromise in an effort to build support for Democratic initiatives. President Cleveland, a Gold Democrat, was not inclined to compromise on a proposal to repeal the Sherman Silver Purchase Act. Gorman, as chair of the Democratic conference, sought to mollify the opponents of repeal by offering concessions, which Cleveland regarded as betrayals. An even more serious break with the president came when the Senate, in 1894, took up tariff reform. Gorman once again sought consensus through compromise and, in the process, mangled the president’s declared intent to use the tariff merely as a source of revenue, not an instrument of protection from foreign competition.9

Relations between Cleveland and Gorman had cooled even before the tariff and silver disputes. Gorman had managed Cleveland’s first campaign for the presidency in 1884. But in 1892, when Cleveland made his comeback, Gorman was rumored to be considering a run for president himself, and he kept his distance from the movement to put the ex-president back in the White House. By 1894, the break between the two men was complete, and Cleveland pointedly demonstrated his alienation from Gorman by pressuring Rasin to arrange the election of Gorman’s archenemy, John K. Cowen, to the House of Representatives.10

Maryland’s Democrats were solid supporters of President Cleveland. So was Freeman Rasin, but he now bore the burden of his long partnership with Arthur Gorman. Gorman would not face reelection to the Senate until 1898, but Rasin had to endure a municipal election in 1895, and many reform-minded Baltimoreans regarded the defeat of Rasin as a first step toward unseating Gorman. On the defensive, the Rasin organization reverted to election-day violence not seen since the Know-Nothings. Frank Kent declared it the “last disorderly election” in the city. Several black voters were reportedly shot and killed, and Reform League poll watchers were assaulted by machine toughs. The Sun did not confirm the killings but declared that “rowdyism was rampant,” especially in the Seventeenth Ward, and “gangs of repeaters were housed about town,” but Reform League poll watchers could not get the police to take any action against them. This time, however, neither voter fraud nor the machine’s muscle men could hold back the Republicans. They took control of both city and state governments, and grew even stronger after the election of William McKinley as president in 1896, when they gained the federal patronage that the Democrats lost.11

REFORM TRIUMPHANT

The new mayor, in 1895, was Alcaeus Hooper, proprietor of a textile mill in Woodberry, just inside the city limits. In Baltimore, the putative Republican boss was William F. Stone, chairman of the city’s Republican committee. The mayor and the chairman soon fell out. Stone had made his debut as a party activist in 1880, and only a year later he was elected executive of the Republican organization in the Seventh Ward, the district where Freeman Rasin began his career as a Democrat more than a decade earlier. Unlike Rasin, however, Stone labored for years with little hope of achieving state or local office. Democrats monopolized those rewards. Republicans had to make do with federal patronage, and perhaps because the spoils were so scanty, the competition was fierce. The party’s internal factions were organized around federal jobs. “Post Office” Republicans squared off against “Customhouse” Republicans.12

Stone stood with the Post Office crowd, and when Republican McKinley succeeded Democrat Cleveland in 1897, Stone gathered endorsements to support his appointment as the city’s postmaster. The incumbent, however, was an Independent Democrat who had campaigned vigorously for McKinley, and the president reappointed him. Stone became Baltimore’s customs collector, a position he retained as long as Republicans controlled the White House.13

Access to city and state jobs did little to reduce Republicans’ internal quarrels about patronage. Mayor Hooper was an energetic advocate of municipal efficiency. He was also stubborn and difficult. His efforts to improve and rationalize the delivery of public services ran headlong into the patronage demands of his fellow Republicans on the city council. The council wanted paying jobs for the Republican loyalists who had been steadfast party workers during the barren years of Democratic hegemony. The mayor wanted competence, and he was willing to hire Democrats or Independents in order to get it. The Republican council was shocked at first, then outraged, and according to the Sun, “the seeming indifference of the Mayor to the storm he . . . aroused by his appointments” only accentuated “the anger of his opponents in that body.”14 In 1896, the council passed an ordinance depriving the mayor of his appointive power. Hooper vetoed it. The council overrode his veto and proceeded to appoint a slate of department heads. Hooper refused to administer the oaths of office. The combatants carried their dispute into the courts, where the council’s position initially prevailed, but the Maryland Court of Appeals sided with Mayor Hooper. It was an empty victory. He still had to get council approval for his appointments.15

Hooper found the work of the mayoralty as obnoxious as the council found him. After six months in office, he complained that a term as Baltimore’s chief executive meant “two years of turmoil, trial, and trouble. There is scarcely a minute which is free of worry. The worst of it is that the worry is usually of a trivial nature about which the executive officer of a big city should not be bothered.” In private corporations, he claimed, executives were never troubled with so much operational detail. The mayor had to oversee 25 municipal agencies. Eleven were governed by boards or commissions; the mayor was required to serve on eight of them and to be president or chairman of five. An obstreperous city council multiplied the miseries of the mayoralty. “A Mayor’s lot,” said Hooper, “is made almost a continuous nightmare if every movement of the executive branch . . . is combated by the legislative branch.”16

A particular point of contention between the mayor and the council was the appointment of the city’s school commissioners. Under the existing arrangement, the councilmen of each ward nominated one of its residents for the board of school commissioners, and then the council as a whole approved the nominees. The practice produced an unwieldy school board of 24 members, most having no particular expertise in matters of education. Early in 1897, before the council began its annual session, Mayor Hooper dismissed most of the school commissioners and appointed six commissioners to replace them. One of them was a woman; another was president of Johns Hopkins University, who served as president of the commission; three of the six commissioners came from a single ward—the Twelfth, the city’s silk-stocking district. The commissioners dismissed by Hooper refused to step down, and for several months, Baltimore had two school boards. When the council reconvened, its members voted to challenge the mayor in court, and this time the court of appeals sided with the council.17

Baltimore’s Reform League, under the leadership of the sharp-tongued aristocrat Charles J. Bonaparte, was fighting in the General Assembly for a more general reform of public employment in the city—a civil service law limited to Baltimore that would embody Mayor Hooper’s commitments to competence and nonpartisanship. Patronage-starved Republicans and Democratic spoilsmen resisted, but instead of rejecting the measure outright, they shrewdly proposed a constitutional amendment that would extend the merit system to the entire state and require the approval of voters in a referendum. The amendment was rejected overwhelmingly. Less than one-fifth of Baltimore’s voters supported it.18

Apparently emboldened by the public’s rejection of civil service reform, the Post Office and Customhouse Republicans united behind William Stone to deny Mayor Hooper renomination in 1897. By some accounts, at least, Hooper was not much inclined to seek a second term anyway. Before he left city hall, however, several hundred of his friends gathered for a testimonial dinner at the Rennert Hotel. The speakers tried to give a positive spin to Hooper’s irascibility. One of them proclaimed that “we want a Mayor who doesn’t care . . . about ‘harmony’ . . . no sensible community elects and pays its chief officer to ‘harmonize’ with its plunderers or its vermin.”19

REPUBLICAN INSURGENCY

William Stone’s Republican organization, its plunderers and vermin, decided not to endorse anyone to succeed Hooper as mayor. Stone was initially inclined to support J. Frank Supplee, Republican loyalist, militia officer, prohibitionist, local dry goods merchant, a founder of the Merchants’ and Manufacturers’ Association, and locally famous as enthusiastic organizer of parades for almost any occasion. His chief opponent was William T. Malster, a man with little or no formal education who had worked his way from deckhand on a steamship to ownership of the Columbian Iron Works and Dry Dock Company, with a 13-acre shipyard on Locust Point where workers built naval vessels and some of the earliest oil tankers. While he campaigned for the mayor’s office in 1897, his shipyard would launch one of the first practical submarines. He was founder and leader of a relatively new Republican organization, the Columbian Club, and had support among many of the party’s ward organizations and workers, including many African Americans. Chairman Stone and the city’s central Republican committee chose to let the Republican voters decide which of the two mayoral aspirants would be the party’s nominee.20

They soon had reason to regret their neutrality. According to the Sun, the “intense bitterness of factional feeling . . . engendered in the red-hot contest between Col. J. Frank Supplee and William T. Malster” threatened to tear the party apart. A committee of Republican businessmen urged Stone and the city’s Republican committee to endorse a unity candidate and press Malster and Supplee to withdraw in the interest of party consensus. The compromise nominee was millionaire businessman Theodore Marburg, who, like Mayor Hooper, stood with the party’s reform wing, but seemed far more agreeable than the mayor. He was described as a “man of great gentleness,” “the greatest tact and consideration,” who wrote poetry, campaigned for world peace, and later headed the Municipal Art Society.21

Neither Malster nor Supplee would stand down. Malster filed suit to challenge the rules laid down for the primary by the Republican committee. The court denied his request for an injunction on the grounds that it had no jurisdiction. The dispute had to be resolved within the party. Malster decided to have a primary of his own. As its only candidate, he won easily. One of his more devoted followers was arrested when he tried to vote twice.22

Marburg and Supplee ran against one another in a separate Republican primary. In the interest of party harmony, the two candidates were allocated different wards in which to campaign so that they would not have to confront one another. Supplee won more votes, but Marburg got the nomination when delegates from two of Supplee’s wards defected at the convention, on the evening after the primary. More significant than the outcome, however, was the difference in voter turnout between the two Republican primaries. Malster drew more than 18,000; Marburg and Supplee, roughly 4,000 less. Later that summer, the Republican state convention in Ocean City threw out the results of both primaries. Supplee abandoned his candidacy because Malster seemed to be the choice of most Republican voters, and it was “useless for any one to enter the lists against him.” He declared that he was finished with politics and made a point of resigning from all the Republican clubs to which he belonged. (The next year he would secure appointment as city register.) Marburg also stepped aside. His disavowal of politics was permanent.23

The Reform League, though uncertain of Malster’s progressive credentials, preferred him to the candidate of the Gorman-Rasin Ring, whose inclinations were well-known.24 Malster won and promptly confirmed the reformers’ worst suspicions. A legion of Republican office seekers marched behind him into city hall. Local reformers, usually advocates of municipal improvements, were leery of Malster’s proposals for public works because they suspected that the projects were pretexts for patronage. But they welcomed another mayoral initiative. Malster appointed a bipartisan commission to draft a new city charter to overcome the administrative disjointedness and inefficiencies of ward-based government and increase his own power as mayor. The commission included Daniel Coit Gilman, president of Johns Hopkins University; former Democratic mayor Ferdinand Latrobe; and the venerable William Pinkney Whyte, ex-governor, ex-senator, and ex-mayor.

The committee’s draft, approved by the General Assembly in 1898, was a significant step toward the centralization of Baltimore City government. It extended the mayor’s term in office from two to four years. A three-quarters vote of the city council would be needed to override a mayoral veto. The new charter created a five-person board of estimates, chaired by the president of the second branch of the city council but generally dominated by the mayor. Two of the board’s five members—the city solicitor and the city engineer—were mayoral appointees, and their votes, along with the mayor’s, made for a prevailing mayoral majority. The board would prepare the city’s budget for the approval of the council and vote on major city contracts. The council might reduce the budget prepared by the board of estimates, but it could not increase any item of expenditure. The charter also gave the mayor unambiguous authority to appoint the heads of all city departments and the key role in appointing school commissioners. There were also changes in municipal elections, which were to be held in May instead of October to separate them more fully from state and federal contests in November. In addition to the mayor, the president of the council’s second branch ran for office citywide, as did candidates for the office of city comptroller. The charter also redrew the boundaries of the wards, disrupting the neighborhood power bases of the ward bosses, another step toward political centralization.25

By the time Baltimore’s new charter took effect, the General Assembly’s Republican majority had voted Arthur Pue Gorman out of the US Senate.26 George L. Wellington, Republican state chairman and architect of Democratic defeat, had already captured Maryland’s other Senate seat. The Ring seemed vanquished. “By the time it was all over,” Sonny Mahon recalled, “you couldn’t find a Democratic officeholder with a finetooth comb.”27 To make matters worse, the presidential contest of 1896 scrambled Democratic loyalties in Maryland, where most Democrats decried the silver coinage plank on which William Jennings Bryan grounded his campaign. Baltimore gave McKinley almost 61,000 votes to Bryan’s 41,000.28

With Bryan’s defeat, Baltimore’s Democratic organization lost the federal patronage that had helped to sustain it under Grover Cleveland. Rasin’s organization began to unravel. Sonny Mahon, Rasin’s chief lieutenant, had drifted away from the boss in a quest to become a boss in his own right. Arthur Gorman seemed ready to part company with Rasin, too.29

But the Republicans faced serious internal schisms. Mayor Malster’s 11 stalwarts in the General Assembly refused to enter the Republican caucus, thus preventing the Republican majority from electing a Speaker. The Malster Republicans allied with the Democratic minority to place a Malster man in the leadership position. (The new Speaker was later convicted as a jewel thief.) Malster’s preemption of his party’s attempt at legislative leadership was regarded as a gambit to advance his own unannounced ambitions for a seat in the US Senate.30

In the Republican mayoral primary of 1899, Malster defeated Alcaeus Hooper’s attempt at a comeback, but Baltimore’s voters were as fed up with Malster as they had been with the Democratic Ring. Freeman Rasin was shrewd enough to realize that his open sponsorship of any mayoral aspirant might handicap the candidate. He made a show of indifference about the contest: “I’m getting tired of it. I’m going to wash my hands of the whole business. Let the rest of these fellows get their candidate.” A new “Democratic Association of Baltimore City” would settle on a candidate and orchestrate a “people’s campaign.” In fact, Rasin stayed in close but quiet touch with the group’s leader. But his power had clearly diminished. From this time forward, he would support Democratic mayoral candidates chosen by the Independent Democrats and settle for a share of city patronage.31

The 2,500 members of the Democratic Association agreed that their party’s mayoral candidate should be Thomas G. Hayes, a former US attorney for Maryland and one-time Democratic candidate for governor. Gorman and Rasin gave their assent, but said nothing in public.32 Hayes campaigned as an Independent Democratic reformer. His past denunciations of Arthur Gorman gave him credibility in the role. In the ensuing election, the Democrats won not only the mayor’s office but also the comptroller’s, every seat in the second branch of the city council, and all but 6 of the 24 seats in the first branch. The Baltimore American, which had endorsed Malster, acknowledged that the election was “the most orderly and the most honest ever held in Baltimore.” But racial animosity played an undeniable role in the Democratic comeback. Malster’s Republican administration, wrote Frank Kent, “with its political pirates and negro office-holders, had pretty well disgusted the public.” The New York Times agreed that the “race question largely entered into the election, the feeling against the Negro being very strong.”33

Race also figured in Arthur Gorman’s plans for a political comeback as a US Senator. His strategy was to shrink the Republican electoral base by disenfranchising some of the state’s 53,000 African American voters, many of whom turned out reliably for the party of Lincoln. Early in 1901, the General Assembly approved a new election law ostensibly aimed at illiterate voters but intended to disenfranchise black voters, many of whom were illiterate. It eliminated all party emblems from ballots, which, according to H. L Mencken, “became Chinese puzzles to the plain people, who had been voting for Abraham Lincoln’s beard or the Democratic rooster for years.” Candidates’ names were grouped by the offices they sought rather than their party affiliations. Voters were barred from receiving any assistance at the polls.34 The first outing for the new law occurred in Baltimore’s council elections in May 1901. The ballot law backfired. Republicans held coaching sessions for illiterate voters so that they could recognize the names of Republican candidates for the council. The Democrats offered classes too, but Democratic illiterates were apparently less willing to accept instruction. Republicans won 17 of the 24 seats in the council’s first branch, and all 4 in the second branch that were up for election.35

Gorman’s chances of regaining his US Senate seat depended on the state legislative elections occurring later in 1901. He attacked the Republican Party for its dependence on the black vote, and then chided African American voters for being misled by “designing men” who used them for political advantage. Republicans held their own in Baltimore, in spite of the literacy law. But Gorman won sufficient support outside the city to return to the Senate.36

REFORM BOSS

While Arthur Gorman tried to alter the racial composition of the state’s electorate, Freeman Rasin was left to cope with Independent Democratic mayor Thomas G. Hayes. To his regret, Rasin discovered that Hayes was not only a progressive reformer but a potential rival for the role of Democratic boss and prince of patronage. He was the Democratic counterpart of Republican William Malster—a Reform boss. Progressive reformers perceived the same duality in Hayes. Charles J. Bonaparte warned that the mayor’s attempt “to combine a ‘business administration’ with the abuses of a ‘spoils’ politics is a task as hopeless as to build a fire in a vessel of water.”37 But for a time, at least, Hayes made the combination work. Reformer Hayes appointed the president of the Reform League to head the school board and advocated the insulation of public schools from partisan politics; he named professionals as city engineer and health commissioner and introduced civil service examinations for applicants to the Fire Department. He was the first mayor to organize a municipal cabinet. It met once a month. But Boss Hayes used patronage appointments to win over some lesser Democratic bosses, including Sonny Mahon, in an effort to build his own machine for the next mayoral election.38

Hayes, however, was no good at maintaining alliances. Mencken, then a young city hall reporter for the Baltimore Herald, later described him as “an extremely eccentric and rambunctious fellow, so full of surprises that he had already acquired the nickname of Thomas the Sudden . . . There never lived on this earth a more quarrelsome man.” “He was,” Mencken added, “a really first-rate public official.” He also had an unusual appetite for detail. His first annual message in 1900 went on for 72 typed pages and included observations about the chapel ceiling at the city jail and the supply of ice for the Quarantine Hospital.39

Hayes was the first mayor to take office after approval of the city’s new charter in 1898. He made the most of the enhanced powers of his office, but failed to achieve success in several of his most significant projects. His health commissioner was powerfully convinced that the city needed a special hospital for patients suffering from infectious diseases—diphtheria, scarlet fever, and measles. (The Quarantine Hospital was for sick passengers and crew members from arriving ships.) Mayor Hayes supported the project, which also had the support of physicians at local medical schools.40 No one seemed to oppose the project in principle. But no one wanted to live in the vicinity of a hospital for patients with infectious diseases. A majority of the city’s delegation in the General Assembly supported a bill introduced by Republican delegate William Broening that prohibited construction of the hospital within half a mile of any public park. The measure prevented the city from using a parcel of land already purchased for the infectious diseases facility.41

The mayor faced more complicated hindrances in his pursuit of another high-priority project: construction of a municipal sewer system. Mencken reported that cesspool leaks, overflows, and illegal drains converted the Basin into an open sewer and gave Baltimore “a powerful aroma every spring and by August [it] smelled like a billion polecats.”42 Almost every big city already had a sewer system, but Baltimore continued to rely on belowground cesspools and a fragmented collection of half a dozen neighborhood sewers. Privy vaults were usually “dug to water.” Many residents relied on neighborhood pumps that drew on the same aquifer. Aside from the associated smells and diseases, cesspools reduced the land area for building construction, diminishing the space available for development in a growing city and hindering the growth of municipal property tax revenues.43

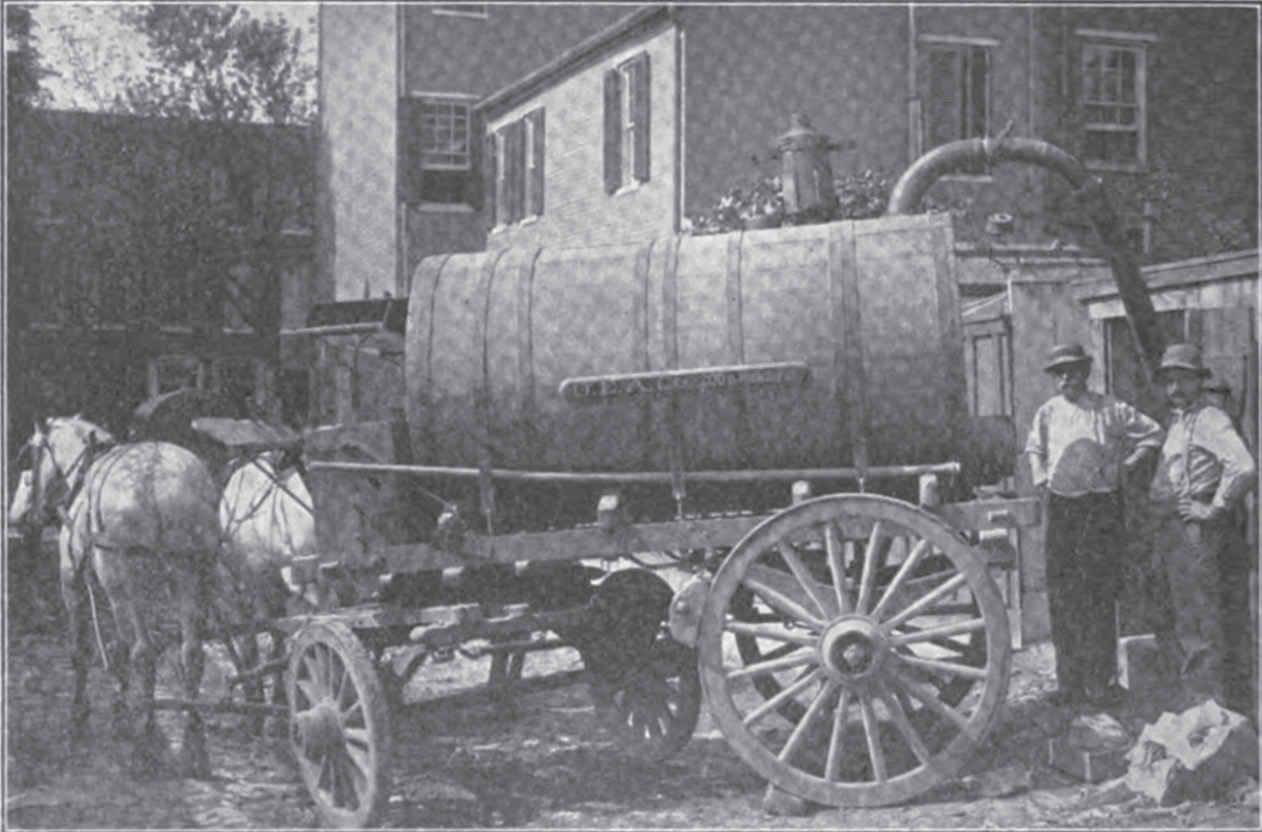

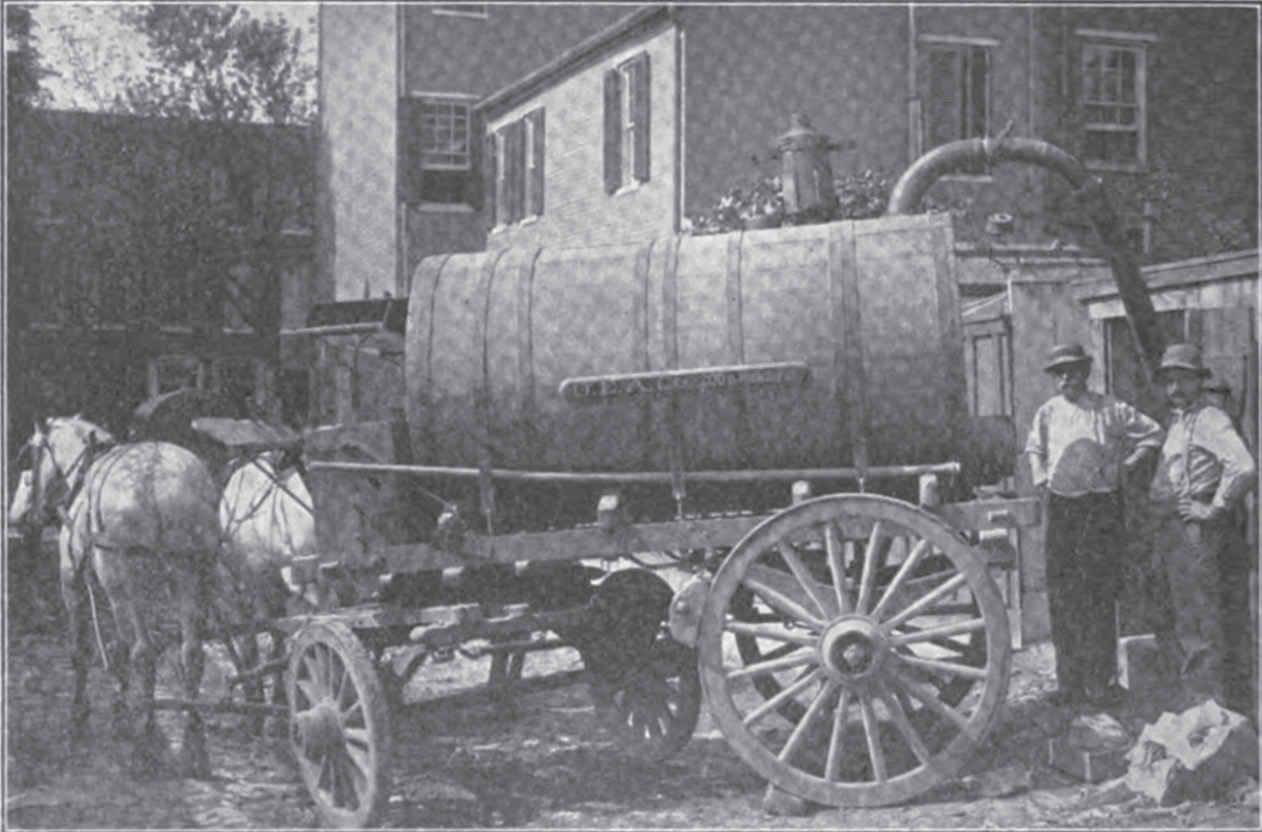

The status quo had its friends. The Odorless Excavating Apparatus Company and its franchise holders profited from the council’s longstanding failure to build a citywide sewer system. By 1900, the company virtually monopolized city contracts for the disposal of “night soil” and employed hundreds of workers. According to Mencken, two members of the city council held Odorless Excavating franchises, and the company spread its good fortune by selling its accumulated sludge to local fertilizer firms.44 Freeman Rasin’s brother owned one of them, but there is no hard evidence that he was an Odorless Excavating customer.

The city’s chief expedient for both wastewater and storm-water management had been to “tunnel” some of the streams that passed through the city, waterways now invisible, unsmellable, and long forgotten. Tunneling was a less costly but less effective alternative to a sanitary sewer system, which might require the expenditure of $10 to $12 million.

In 1901, Mayor Hayes secured authority from the General Assembly to borrow up to $12 million for such a system. The bill that Hayes proposed also authorized him to appoint a sewerage commission that would oversee planning and construction. As mayor, he would lead the commission. Under questioning from members of Baltimore’s legislative delegation, Hayes disclosed a curious feature of his tenure on the commission: he would continue to be its chairman even if he were no longer mayor—with a voice in decisions about spending millions of dollars and hiring hundreds of workers. The vote was close in the General Assembly, but the measure passed.45

The Odorless Excavating Apparatus Company at work.

Hayes secured additional funds for his sewer scheme. He orchestrated the sale of the city’s railroad—the Western Maryland—for more than $8.7 million. In 1902, the mayor sent an ordinance to the city council providing for a sanitary sewer. It included a provision that would authorize him to use “the unexpended balance of the purchase money of the Western Maryland Railroad, which is not needed by the Commissioners of Finance to meet . . . the outstanding indebtedness of the Mayor and City Council”—about $4.4 million.46 One of the city’s habitual misjudgments—a bad railroad investment—had unexpectedly yielded the resources to address one of its chronic embarrassments: the municipal stench.

Freeman Rasin fumed on the sidelines. While Hayes was mayor, according to Frank Kent, Rasin “was wont to sit in his office and curse him fervently by the hour. It was about the only fun he had at that time.” And, since the 1898 charter extended the mayor’s term to four years, Rasin would have to endure Hayes at least until 1903. But the members of the city council stood for election every two years, and Rasin went on the offensive in the council primaries of 1901. Rasin Democrats challenged Hayes Democrats. In the general election the two factions turned on one another, and Republicans won control of the council.47

The city council that received Mayor Hayes’s sewerage ordinance in 1902 was therefore controlled by a new Republican majority, and while most Republicans supported the building of a sewer system, they wanted it to be done under their auspices, not Mayor Hayes’s. They approved a bill to appoint a sewerage commission of their own in preference to the one headed by Hayes. But there was also a third option. In 1893, during one of his seven terms as mayor, Ferdinand Latrobe had appointed his own sewerage commission. It completed the first stage of its unhurried deliberations in 1897 with a 230-page report containing a plan for a sewer system that would cost over $10 million. Debate about the report dragged on for almost two years. The principal dispute concerned the disposal of sewage—whether it should be dumped into the Bay (“dilution”) or undergo filtration through a 500-acre bed of sand and soil in Anne Arundel County. Latrobe’s sewerage commission submitted a second report dealing with these questions during the Malster administration, not long before Hayes became mayor.48

The Hayes administration used the old commission’s reports to preempt the sewerage commission contemplated by the Republicans. The board of public improvements, a body created under the city charter of 1898 and appointed by the mayor, sent the Republicans’ ordinance back to the council “with our disapproval on the ground that it would cause a delay in sewer construction” that was “both inadvisable and unnecessary . . . Every phase of the sewerage question” had been “studied, investigated, and reported” by Mayor Latrobe’s sewerage commission, which had “six years’ time and the benefit of the study and advice of the best sanitary experts in this country and in England.” Another commission would accomplish little more and waste both time and money.49 But the unresolved disagreement between the Republican council and the Hayes administration about the sewerage commission meant that there would be no progress at all.