FIRE, SMOKE, AND SEGREGATION

THE CONSTRUCTION OF A SANITARY SEWER SYSTEM was a top priority for Baltimore’s new mayor, Robert M. McLane, when he took office in 1903. He was one of the Democratic reformers that Freeman Rasin had recruited to “perfume” his ticket. McLane looked nothing like his predecessors in office—slim, with no moustache, chiseled jaw, impeccable attire. Local tailors pronounced him one of the city’s best-dressed men and reported that many of their customers were trying to match the mayor’s look.1 He had other qualifications. He came from a distinguished family of ambassadors, US senators, members of Congress, and a B&O president. An uncle had been the state’s governor, and McLane himself was formerly state’s attorney for Baltimore. He won support from both organization and reform Democrats. After his unhappy experience with Mayor Hayes, Rasin was willing to support McLane, but only if the remaining positions on the Democratic ticket were assigned to loyal organization men. Rasin chose a longtime loyalist from the Twelfth Ward, W. Starr Gephart, to run for presidency of the upper house of the city council; Gephart had already been president of the lower chamber. The search for a city comptroller was more difficult. Several eligible organization men declined the position, and the search finally settled on an obscure candidate recommended by two ward leaders as “true blue” and a “Muldoon” (Baltimore’s term for Democratic straight-ticket voters). He was Harry Hooper, an $18-a-week clerk at an ice company. When the young man received the news of his anointment from his ward boss, he was so surprised and delighted that he wept.2

The 1903 primary was the first conducted under state law rather than the auspices of the political parties. The Democratic forces were badly divided. Freeman Rasin and Sonny Mahon were going through one of their periods of political estrangement. McLane benefited from the support of both bosses, but Mahon’s forces fought to defeat Rasin’s candidates for comptroller and council president.3

McLane easily defeated Mayor Hayes, but he won the general election by only a narrow margin over Republican congressman Frank C. Wachter, who had seized his party’s nomination in opposition to the choice of William Stone and his organization. Stone’s Republican candidates for comptroller and council president defeated both of McLane’s Democratic running mates. Gephart and Hooper, according to Frank Kent, were fatally tainted by their association with Rasin.4

Baltimore City Hall and the ruins left by the fire of 1904, between Calvert Street and Guilford Avenue. Courtesy Maryland Historical Society, Item MC4709

McLane took office, therefore, with two city officials of the opposition party and a Republican opponent who challenged his 520-vote victory as a product of electoral fraud. Things would soon get even worse for the new mayor. On the morning of Sunday, February 7, 1904, a fire broke out in a dry goods store on the western side of Baltimore’s business district. At first only billows of smoke were visible, but the first firefighters on the scene reported a sudden explosion, and then a strong southwest wind carried embers and flames eastward across the center of the city. Another explosion occurred when the fire reached a wooden box on the sidewalk in front of a hardware store. The box was filled with gunpowder and cartridges, and its detonation damaged several nearby buildings, exposing their inflammable interiors. More fire companies responded, but their hoses were ineffective. The flames were so hot that it was difficult to get sufficiently close to play water on them. The firefighters soon resorted to explosions themselves, after receiving authorization from Mayor McLane, to destroy buildings in the path of the conflagration with dynamite. Additional firefighters arrived from Pennsylvania, New York, Delaware, Washington, and Maryland counties. Because the fire had broken out on a Sunday when hardly anyone was at work downtown, no one was killed and few were seriously injured. But by the time the fire had finally burned its way to the Jones Falls and the harbor more than a day later, 140 acres of the city lay in blackened ruins—including the 60-acre plot laid out 175 years earlier as Baltimore Town.5

RECOVERY

Mayor McLane appointed a 63-member Citizens Emergency Committee to devise a rebuilding program for the “Burnt District.” Its chairman was local industrialist William Keyser. The committee was an assembly of the city’s elite, all but a dozen of its members listed in the social register. Keyser appointed subcommittees. Only days after its formation, the legislative subcommittee produced a draft bill for the General Assembly that would create a Burnt District Commission, its five members to include the mayor and two members of each political party. The bipartisan commission would carry out the reconstruction plans of the emergency committee. Its chair was Sherlock Swann, a former city council member and grandson of Governor Thomas Swann. Since the fire had destroyed most downtown office space, the commission operated out of the janitor’s room in city hall. The city council appropriated $1 million of the funds generated by the sale of the Western Maryland Railroad to get the commission started on its rebuilding plans.6

The state legislature authorized Baltimore to borrow another $6 million to pay for reconstruction of the city’s streets and waterfront. Less than a month later, the General Assembly empowered the city to issue yet another $10 million in city stock to finance construction of the long-delayed sewer system. Work on the street and sewer projects had to be pursued in tandem. It made little sense, after all, to repave the streets and then dig them up again to lay sewer mains. City officials hoped not just to rebuild Baltimore but to improve it. The council, for example, wanted to replace cobblestones with paving of a less bone-jarring sort, and it passed a bill appealing to the General Assembly to outlaw cobblestones. Mayor McLane vetoed the ordinance, not because he favored cobblestones, but because he insisted that the city should make its own decisions about paving materials.7 McLane also made it his policy to return all contributions for the relief of the city that came to Baltimore from around the country. He thanked the donors for their kindness, but seemed to see recovery from the fire as an opportunity for the city and its residents to test their own resources, perhaps to overcome the disjointed politics that had handicapped the town since its founding.

In addition to the $16 million in borrowing approved by the state legislature and the funds remaining from the sale of the Western Maryland, the Burnt District Commission could impose an assessment on any property owner who benefited from improvements made in the course of reconstruction. As much as one-third of the cost of these improvements could be charged to the landowners who profited from them.8

Like the British invasion of 1814, the Great Fire animated Baltimoreans to marshal their city’s constructive energies in the face of a crisis that lifted their city out of its chronic inertia and fragmentation. But, in some respects, the rebuilding of Baltimore proved to be more complicated and contentious than defending it against the British. Simply finding property lines and street levels beneath the rubble kept city surveyors busy for months. The task of removing debris occupied 10,000 workers. The Burnt District Commission was empowered to take property by eminent domain, but the exercise of this power was complicated by recalcitrant property owners, often backed by the Republican majority of the council’s second branch. Wider streets were needed, not just to ease the flow of traffic, but to retard the spread of future fires. The street-widening proposals met with opposition among property owners who objected to the downsizing of their lots and anticipated increases in their taxes. The plans for Baltimore Street provoked particular contention and aroused property owners and their attorneys to fight condemnation of their real estate. The skirmish kept the Burnt District Commission from acquiring the property that it needed, and Baltimore Street today, unlike Lombard and Pratt, is no wider than it was before the fire.9

Baltimoreans living outside the Burnt District worried about the effect of the redevelopment plan on their tax bills. Residents in the area annexed to the city in 1888 complained that the diversion of resources to rebuilding the city center would delay the public improvements they had been promised.10

Some of the city officials who worked with Mayor McLane noted that “his entire appearance at times told too well of the heavy strain under which he was laboring.” After a Friday meeting in May between the Burnt District Commission and the board of estimates, one of the participants asked, “I wonder what is wrong with the Mayor? He is certainly not himself to-day.” But by the following Monday, Memorial Day, the mayor seemed to be in good spirits while he chatted with his wife of two weeks. At about three o’clock, he excused himself, went to a bedroom, retrieved a pistol from a wardrobe, and shot himself in the head.11

REPUBLICAN RECOVERY

Speculation about the mayor’s state of mind filled the columns of local papers. A few prominent Baltimoreans, along with his family, insisted that his shooting was accidental. But there was no uncertainly about the custody of the mayor’s office. It fell to a Republican. Under the city charter, the Democratic mayor was to be succeeded by the president of the second branch of the city council, Republican E. Clay Timanus, a loyal lieutenant of party boss William F. Stone. The city charter prevented Timanus from replacing McLane’s Democratic department heads. As lesser offices fell vacant, however, Timanus and Stone filled them with their own partisans, and Timanus chose the members of the sewerage commission to oversee the long overdue construction of the city’s $10 million sewer system.12

Rebuilding of the Burnt District proceeded more rapidly than expected. Mayor Timanus was intent on avoiding controversies. When the city council proposed to intervene in the contentious territorial disputes along Baltimore Street, he exercised his veto because the measure “would lead to no end of legal complications and great expense to the City, accomplishing no object whatever.”13 Timanus intervened in other disputes between the Burnt District Commission and recalcitrant property owners to break logjams in the commission’s efforts to acquire strategic pieces of real estate.14

At the close of 1906, the commission managed to return more than half a million dollars to the city. By that time, 800 new buildings had arisen to replace 1,343 destroyed by fire. Many of the new structures, however, were considerably larger than the old ones, and they were assessed at $25 million, almost twice the value of the buildings they replaced. The reduction in the number of buildings also reflected the movement of some firms out of the city center; having been forced to leave the Burnt District during reconstruction, they decided to remain in outlying locations.15

Timanus recognized that the fire had created a new horizon of municipal opportunity. At the end of 1904, he invited 39 local organizations to send representatives to meet with a committee of the city council for a “General Conference on Public Improvement.” Neighborhood associations were prominent among the participants. Though most of the city’s residential areas had created such organizations as early as the 1880s, they had seldom concerned themselves with the future of the city as a whole. The conference’s chief objectives were construction of the long-awaited sewage system and substitution of smoother paving materials for the city’s cobblestones.16

The rebuilding effort engendered a more general civic momentum that pushed beyond mere restoration. Timanus appointed the Commission for the Encouragement of Manufacturing Plants in the City of Baltimore.17 In clearing the way for construction of a sewer system, the fire also eliminated the septic tanks and privy vaults that had restricted the land area available for building. After the sewer mains came new streets, many of them wider than before, paved with modern materials that allowed smoother passage through the city at higher speeds than cobblestones permitted. Waterfront destruction gave the city an opportunity to take possession of and improve Baltimore’s harbor facilities.18

The fire proved a fortunate disaster. It unleashed a new era of urban development while killing no one, except, perhaps, Mayor McLane.19 In September 1906, the Greater Baltimore Jubilee and Exposition initiated a weeklong celebration of the city’s recovery from its ordeal and launched a more permanent display of the facilities and advantages that the town could offer to industry. One of the honored guests on the first day of the jubilee was Charles J. Bonaparte, now secretary of the navy in the Roosevelt administration, who joined the governor on the reviewing stand at Baltimore Street and Hopkins Place (temporarily renamed McLane Place) to view the military procession. On the following day, the “Industrial Parade” marched. It was led by its chief marshal, the owner of a local distillery and commander of the militia’s Fifth Regiment, in front of his “staff” of more than 50 business executives clad in black derbies, black coats, white trousers, and white gloves. Next came German social, musical, and athletic associations; then 5,000 B&O employees; and, finally, an extravagant “Artistic Division.” This was led, on horseback, by local parade enthusiast and former mayoral candidate Colonel J. Frank Supplee. Punctuated by marching bands and exotically costumed fraternal organizations, it was a procession of the city’s business firms, their workers, and executives. The companies displayed their products and services on floats. The William Knabe Piano Company had nine of them. The Joseph Wernig Transfer Company marched with 14 floats depicting “the general transfer business in its various forms” and illustrating “the handling of giant pieces of machinery and other articles difficult of management in removal from place to place.”20

Mayor Timanus had gone far toward rebuilding his city. But it was still Baltimore, an underfunded, underrepresented, and underpowered municipality. In 1908, for example, a grand jury report compared the size of the local police force with those in five other cities. Baltimore’s force was not only smaller than the others but smaller in relation to the population it had to protect and police. The city had one officer for every 742 residents. Boston had one policeman for every 333 citizens. New York, St. Louis, and Philadelphia also had higher police-to-civilian ratios than Baltimore. Chicago, with a ratio lower than that in the other four towns, still put one officer on the streets for every 529 residents—almost 30 percent more than Baltimore.21 Baltimore did not even control its own police force. The board of police commissioners held their appointments from the state.

POLITICS AS USUAL

William Stone’s Republican organization supported Timanus for a full term as mayor in the election of 1907. It could hardly do otherwise. As in 1903, the organization’s candidate faced a primary challenge from George Wachter. This time, however, Wachter was defeated. But the battle between Wachter and Timanus made an issue of race. Each Republican tried to outdo the other as a champion of the city’s black population and suggested that his opponent was a covert racist.22 Two politicians declared themselves candidates for the Democratic nomination. Freeman Rasin dithered, uncharacteristically, and then approached former governor Frank Brown. Rasin pledged his organization’s support to any candidate that Brown chose. After extensive discussions with members of Baltimore’s political class, Brown settled on J. Barry Mahool, president of the city council’s first branch. Rasin agreed to the selection. Shortly after Frank Kent interviewed the boss about the new mayoral candidate, Rasin collapsed. A few days later he was dead.23

Tribute came from an unexpected source. The Afro-American acknowledged that Rasin “was a Democrat of the most virulent type, [but] he always had a good side for the colored man.” He had helped to give Baltimore’s black students a high school of their own, and he overcame the school commissioners’ resistance to the hiring of black teachers. “Whatever else he did, Mr. Rasin was never known to come out in abuse of colored people, and it is also known that he cared for more than one colored person who came under his notice. It is fair to assume also, that if Mr. Rasin had not set his face against it, the iniquitous Poe Amendment to disenfranchise the Negroes of this state would have become law.” Rasin “had a warm spot in his heart for the despised race” even though most of its members voted against him.24

The Poe amendment was the Democratic Party’s most ambitious attempt to reduce the Republican electoral base among black Marylanders. It was drafted by John Prentiss Poe in 1905 under the general direction of Senator Gorman, who aimed to shrink the state’s Republican electorate. Poe was dean of the University of Maryland Law School. His amendment would have granted voting rights to men who were qualified to vote before ratification of the Fifteenth Amendment or were lineal descendants of such voters. All others would have to demonstrate that they could explain a portion of the state constitution to the satisfaction of the election judges.25

Maryland voters defeated the Poe amendment by slightly less than 35,000 votes of 104,000 cast. Almost two-thirds of the margin of defeat was rolled up in Baltimore, where the measure lost in 23 of the city’s 24 wards. States further south had successfully used the “grandfather clause” to disenfranchise African Americans, but there were few white immigrants in the South. In Baltimore, however, foreign-born whites made up more than 15 percent of the population, and the grandfather clause would exclude them and their sons from the electorate along with their black fellow citizens. Most of the immigrant voters were Democrats, and an array of white ethnic organizations joined forces with the black Maryland Suffrage League to oppose the Poe amendment. The reform wing of the local Democratic Party launched an Anti-Poe Amendment Association, which claimed 500 members, and Freeman Rasin quietly shifted the weight of his organization against the measure. Four ward bosses openly disowned the Poe amendment. Rasin advised the city’s Democratic candidates to keep quiet about it. When it was all over, the Gorman-Rasin alliance was finished. Rasin claimed that the city’s Democratic organization “did all that could be done for it,” but characterized the Poe amendment as a political burden that had lost votes for the party. An embittered Arthur Gorman died a year after the defeat of his amendment, for which he blamed Rasin, who expired a year later. The imperishable William Pinkney Whyte, ousted from the Senate to make room for Gorman, served out the rest of Gorman’s term.26

PARTY PREJUDICE

Sonny Mahon now succeeded to the leadership of Baltimore’s Democratic organization, along with two other sub-bosses: Frank Kelly and Robert Padgett. Kelly was leader of a ward organization in West Baltimore and a saloonkeeper frequently in trouble with the police for selling liquor on Sunday or maintaining a disorderly house; he usually managed to get out of trouble. Robert “Paving Bob” Padgett was a city contractor who acquired his nickname and his wealth from his work on the city’s streets. The three Democratic leaders followed through on Rasin’s commitment to Mahool as their mayoral candidate, though as a Presbyterian deacon and church treasurer, homebody, “politically and personally clean, straight, sincere, independent, earnest, and thoroughly devoted to the interests of the city,” he was not a candidate of their sort.27 He was, in short, rather colorless, which may explain why he had few enemies and why, in turn, he was chosen as the party’s unity candidate for mayor.

Mahool faced two challengers for the Democratic nomination. George Stewart Brown was a council member. J. Charles Linthicum was a state legislator. They paid no attention to one another. Instead, both attacked Mahool as the candidate of bossism. Their assault was somewhat blunted by the two candidates’ own reliance on the Democratic organization in past campaigns and by the near certainty that either one would seek organization support if he managed to reach the general election. The charge of bossism had also lost some of its efficacy because Freeman Rasin was no longer available as a target, though Linthicum tried to cast Frank Brown as the new boss. George Stewart Brown supported municipal ownership of utilities and streetcar lines and had the backing of the Socialist Workers Party. He tried a variant on Linthicum’s theme. He made Frank Brown the agent of corporate capitalism and Barry Mahool his puppet.28 Mahool’s vote count in the Democratic primary exceeded the combined total for Brown and Linthicum by more than 13,000. He would not do so well against Mayor Timanus in the general election a month later. Mahool had little more to promise the voters than a continuation of the rebuilding and public improvement campaign already begun by his Republican opponent. But there was also the issue of race. It seemed to provide an angle of attack on Timanus, since both he and Wachter had appealed so vigorously for black votes in the Republican primary. Its debut as a campaign theme in the general election was staged to command attention.

Ex-mayor Thomas Hayes had kept to the private practice of law since his defeat for reelection four years earlier. He abruptly resumed the practice of politics days before the general election when he rose to address a crowd of 500 Democrats at a hall in the Eighteenth Ward. Frank Brown joined him on the platform. Hayes declared that he had nothing bad to say about Mayor Timanus. He concentrated instead on the character of Timanus’s political party. The Democratic Party, said Hayes, belonged to “the bulk of the small house owners who pay the principal part of the taxes.” Democratic officeholders were therefore “more likely to be on the lookout for the welfare of this large constituency as to the honest, wise, and economic expenditure of taxes.” Hayes then compared the composition of the Democratic base with the makeup of the Republican constituency. “Who takes the place in the Republican party of the Democratic laboring masses in the Democratic party? Everyone knows it is the colored man, and the bulk of them, we all know, pay no taxes.” Hayes claimed that he was no “enemy to the colored man,” his equal before the law, but said that he was “positively opposed to giving the colored man the franchise until he is properly educated, both morally and mentally.”29

Hayes said nothing new. His speech for the Mahool ticket echoed themes already implicit in Arthur Gorman’s repeated efforts to shrink the black electorate. Gorman, of course, had packaged his prejudice as a concern about voter literacy. Hayes made no secret of his contempt for black voters. It was something he had in common with ex-governor Frank Brown, the Democratic Party’s maestro of the moment who sat behind him on the platform. Brown had voiced similarly candid views about race when he campaigned for Robert McLane in 1903. “What will become of Baltimore,” he had asked, “which has now one-fifth of its population, or 100,000 of the colored people, a larger number than any city in the United States . . . and the only Southern city and State in which the colored people have unrestricted right of suffrage?” The time had come, Brown said, to raise the race issue, because Maryland had “become the chief dumping ground of this worthless class of colored people from the South,” who competed for jobs held by white workers and burdened “our courts, prisons, and asylums.”30

Baltimoreans hesitated to make an issue of race when it threatened to disrupt established relationships and institutions. But when disagreements about race defined the differences between Republican and Democratic candidates, Democratic politicians were prepared to exploit the issue for partisan advantage. They were more guarded, however, when racial offensives were directed against the voting rights of black Baltimoreans, some of whom voted Democratic.

The General Assembly would make two further attempts to win voter approval for constitutional amendments designed to disenfranchise black voters. The Straus amendment, named for Maryland’s attorney general and constructed by a committee of respected Democratic attorneys, was designed to avoid the Poe amendment’s pitfall: excluding foreign-born voters from the polls along with African Americans. The Straus version granted voting rights to foreign-born citizens naturalized after ratification of the Fifteenth Amendment and their direct descendants. The remainder of the state’s would-be voters—black voters—could qualify by owning and paying taxes on at least $500 in real or personal property or by filling out an application form. The form required them to write out not only personal information but the names of the president, at least one justice of the US Supreme Court, the state’s governor, one member of the state court of appeals, and (in the case of Baltimore residents) the mayor. The measure was sold to the voters as a means to elevate the electorate by excluding the illiterate or politically ignorant. A majority of the voters of Southern Maryland and the Eastern Shore supported the proposal, but opposition in Baltimore and the northern counties was strong enough to defeat it. Baltimore City alone accounted for almost two-thirds of the amendment’s margin of defeat.31

Democratic supporters of the Straus amendment nevertheless took encouragement from the outcome. The measure had come closer to victory than the Poe version. It had carried four of the city’s wards instead of just one, and the strong Democratic majority elected to the General Assembly gave them hope that they would have another chance to drive most black men out of the state’s electorate. Their opportunity came in 1911 with the Digges amendment, drafted by Charles County delegate Walter Digges. It gave the vote to all white men who were legal residents of the state and at least 21 years old. Other men had to prove that they had paid taxes on $500 or more in real or personal property for the previous two consecutive years. To enhance the amendment’s prospects, the legislature passed a temporary registration law that excluded all black men from the polls. In other words, the state’s African American voters would not be permitted to vote on the law that deprived them of the vote. But the registration law seemed so outrageous that the governor (who had originally endorsed it) felt compelled to veto it.32

In Baltimore, the Digges amendment lost by almost twice the margin that defeated the Straus amendment. The Republican gubernatorial candidate carried the city, which also elected Republicans as sheriff and state’s attorney. The city’s Afro-American offered its own explanation for the amendment’s defeat.33 Voters—even white Democratic voters—might want to ensure that their party had to compete for their support. A crippled Republican Party might reduce the Democratic Party’s responsiveness to its own “laboring masses.”

LIVING APART

In July 1910, a Yale-educated African American attorney, George W. F. McMechen, rented a house on McCulloh Street. His new home was only 10 blocks east of his old one, but his family’s arrival roused nearby residents to form the Madison Avenue, McCulloh Street, and Eutaw Place Improvement Association. Their objective was to prevent black families like the McMechens from moving into their white neighborhood. Milton Dashiell, a white lawyer who lived on McCulloh Street, drafted an ordinance designed to achieve the organization’s aim. He outlined its provisions for his fellow residents at a meeting of the new association. The ordinance would prohibit African Americans from moving to blocks where a majority of the residents were white, and whites from moving to blocks with African American majorities. It sounded even-handed, and Dashiell justified it by referring to Baltimore’s racially segregated schools. If white children could not be required to spend part of each day with black children, why should white adults have to live day and night with black neighbors?34

The ordinance was an improvised response to an immediate grievance. The proposed measure did not cover the entire city, just a section of Northwest Baltimore.35 But it made Baltimore the first city in the country to attempt residential segregation by law. Inquiries came from Roanoke, Richmond, Norfolk, Winston-Salem, Atlanta, and elsewhere asking for copies of the law. As the audience grew, so did the ordinance. It was extended to the entire city.

The segregation law was introduced by Councilman Samuel L. West of the Thirteenth Ward. Dashiell and his aroused neighbors were residents of the Seventeenth, but West’s home was just a few blocks from McCulloh Street. Citizens who spoke at hearings on the proposed ordinance were overwhelmingly in favor of its passage. Some suggested that it would preserve the city’s tax base by forestalling white flight to the suburbs. Two of West’s colleagues, however, raised objections. One councilman suggested that restrictive covenants in property deeds would achieve residential segregation more effectively than a city ordinance that was sure to face legal challenges. The only black councilman, Harry Cummings, raised just such a challenge. He moved that consideration of the West ordinance be suspended until the city solicitor could rule on its constitutionality. His motion was defeated.36

Hearings were extended so that the bill’s opponents might be heard. Emma Traxton, representing the Federation of the Colored Christian Women of Maryland, argued that “intelligent negroes” were “moving away from hovels to avoid disease from spreading among them and that they are anxious to uplift their race.” A black clergy-man, A. L. Gans, offered a similar explanation: black Baltimoreans “moved to the streets where white people lived simply to better their condition and environment.”37

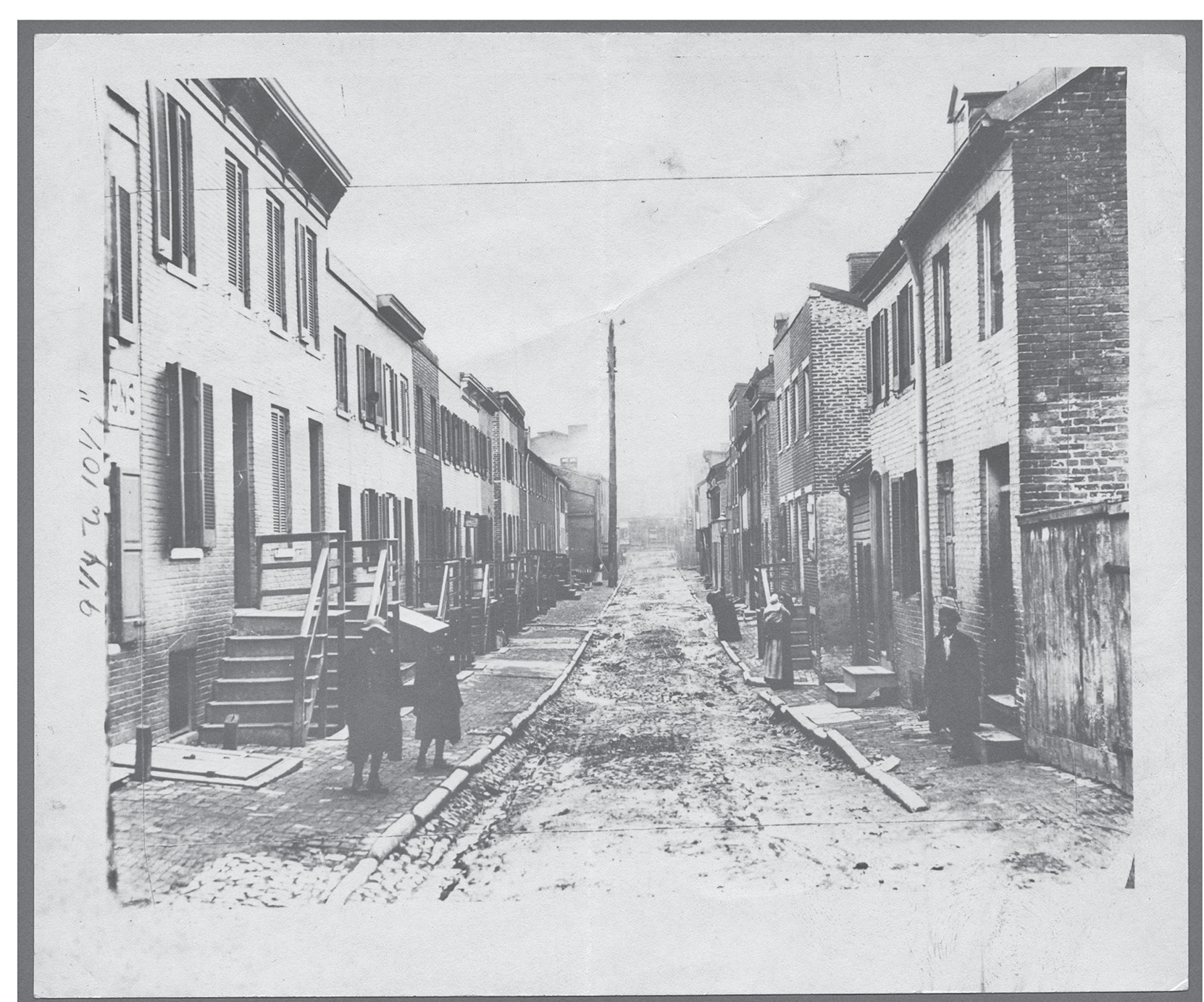

Biddle Alley in 1911. Before they were confined to ghettoes, many of Baltimore’s African Americans were confined to alley housing within walking distance of the white households and business firms that relied on their labor. Biddle Alley was notorious as Baltimore’s “Lung Block,” with the highest rate of tuberculosis in the city. Courtesy Maryland Historical Society

The council approved the West ordinance and sent it to Mayor Mahool, who referred it to city solicitor Edgar Allan Poe (the author’s grandnephew) for an opinion on its constitutionality. Poe ruled that the ordinance represented a legitimate exercise of the city’s police powers—a measure designed to preserve public order against the “disorder and strife” likely to erupt in racially mixed neighborhoods. The mayor then signed “An Ordinance for Preserving Peace, Preventing Conflict and Ill-Feelings Between the White and Colored Races, And promoting the General Welfare of the City of Baltimore By Providing As Far As Possible for the Use of Separate Blocks By White and Colored People For Residences, Churches, and Schools.”38 City officials were making an issue of race, in other words, to avoid the interracial friction that might compel them to address the issue of race.

The segregation ordinance endured as many reversals as had the various amendments designed to disenfranchise black voters. This time it was the courts, not the voters, who proved obstructive. The first version of the West ordinance failed to make it out of the city. Two judges on the Baltimore Supreme Bench ruled it improper because of its much-too-long title. Under the city charter, the title of an ordinance was supposed to specify a single subject to which it was addressed. The ordinance went back to the council for revision. Councilman West turned to a new legal adviser, William Marbury, to replace Dashiell. In addition to fixing the title, Marbury exempted racially mixed blocks from the law’s provisions, but the legal verbiage he used was open to several interpretations. Dashiell, who was ill and unable to attend the hearings on the new version of his ordinance, wrote to Mayor Mahool urging that the ambiguous section be scrapped. Racially mixed neighborhoods, he argued, were precisely the ones “creating a condition for conflict, which the Ordinance is designed to obviate.” Mahool signed it anyway, but it was repealed and reenacted by the council a month later because of a procedural error in its approval, and new provisions were added that applied to the location of churches and schools belonging to the two races. Mahool signed this on May 15, 1911. It was the last official act of his term as mayor.39

For two years, the West ordinance stood legally undisturbed. Then, in 1913, John E. Gurry, a “colored person,” was charged with occupying a house in a white block. He was represented by W. Ashbie Hawkins, a law partner of George W. F. McMechen and the owner of the house on McCulloh Street that McMechen had rented. The case against Hawkins’s client was dismissed in Baltimore’s criminal court on the grounds that the ordinance’s provisions made no sense. William Marbury’s language concerning racially mixed blocks could be interpreted as making it illegal for anyone—white or black—to move in. The case went to the state court of appeals, which interpreted Marbury as he intended, but rejected the West ordinance all the same because it could prevent a white person who already owned a house on a majority-black block from occupying it. The same was true for a black owner of a house on a white block. The city council stood ready with a fourth version of the West ordinance, revised to preserve property rights already in force before enactment of the law.40

Baltimore’s experiment with residential segregation by law was taken up in other cities, but not for long. In 1917, the US Supreme Court considered a case from Louisville, which had its own version of the West ordinance. The law was held unconstitutional, not because it was racially discriminatory, but because it infringed on the rights of property by dictating the race of the persons to whom landlords or homeowners could rent or sell their real estate.41

Baltimore’s prolonged legal struggle to secure its residential segregation ordinance was notable not just because the law was the first of its kind but because the politicians who orchestrated the effort could hardly be portrayed as reactionary racists. Mayor Mahool endorsed female suffrage, the eight-hour day, utility regulation, a minimum wage, playgrounds for poor children—and residential segregation.42

Reformers in Baltimore adhered, like progressives elsewhere, to the encouraging hypothesis that the physical environment of the slum produced the deviant behavior of slum dwellers. A reduction in overcrowding and improvements in air circulation, toilet facilities, water supply, and exposure to sunlight would mitigate the poverty, immorality, and criminality of the people who lived in substandard housing. But the reformers’ faith in environmentalism wavered when confronted with the black slum. The Baltimore Charity Organization Society and the Association for Improving the Condition of the Poor jointly sponsored a study of local housing conditions, completed in 1907. Its findings in two districts of “alley housing” inhabited by “light-hearted, shiftless, irresponsible” African Americans set the investigators “wondering to what extent their failings are the result of their surroundings, and to what extent the inhabitants, in turn, react for evil upon their environment.”43

The housing study, however, did not recommend racial segregation, and Baltimore’s foremost progressive reformer, Charles J. Bonaparte, was an outspoken opponent of the West ordinance.44 Other members of the progressive elite remained silent and left the defense of white Baltimore to “middling whites who had vested interests in a neighborhood.” In its assaults on the ordinance, the Afro-American Ledger made a point of emphasizing the inferior social standing of the whites who turned out for meetings in support of the segregation law. Gretchen Boger finds that the Afro’s assessment of the segregationists’ status is confirmed by evidence from city directories and the social register.45 The segregationists may have appropriated progressive rhetoric about public health or eugenics to advance their campaign, but their chief concern was to defend their neighborhoods from racial change and to protect the market value of their homes. The residents of elite Mount Vernon faced no such threat. Few blacks could afford to live in the neighborhood except as domestic servants. Roland Park, the sylvan, Olmsted-designed development on the city’s fringe, relied not only on home prices but on restrictive covenants in property deeds that prevented residents from selling their homes to African Americans, Jews, or Catholics.46

Progressivism, according to Boger, was not the ideology that drove Baltimore’s innovative campaign to achieve residential segregation by law.47 Nor was segregation simply a measure to protect property values in white neighborhoods. Whites’ concern about property values was inseparable from widespread Negrophobia. On that subject, one of the local experts was William Cabell Bruce, city solicitor, sometime mayoral candidate, and, eventually, US senator. In 1891, he had published a pamphlet titled The Negro Problem. It explained that emancipation had provoked the impulse toward segregation. The slave owner could allow “a considerable latitude of personal intercourse between himself and his slaves” because “no individual familiarity or indulgence could possibly efface the line of deep demarcation that the law had prescribed.” Once that boundary disappeared, “it became impossible for the whites to allow themselves the same liberality without running the risk of having their race susceptibilities irritated in many different modes.” When black men gained political citizenship, the gulf between the races grew even wider. “What the negro has gained in political privileges,” wrote Bruce, “he has lost twice over in social. The freer his access to the polls, the more difficult has become his access to all the human relations that law cannot touch.”48 Rev. Harvey Johnson delivered a spirited refutation of Bruce on the question of African inferiority, but he did not address Bruce’s observations about the etiology of white prejudice—its intensification in response to the removal of racial barriers.49

White Baltimoreans were long accustomed to living with free black people. Many whites regarded them as undesirables, but in a pedestrian city it was difficult to avoid contact with them, except by persuading them to leave for Liberia. Physical separation became feasible when streetcar lines enabled whites of the better sort to sift themselves out from less prominent Baltimoreans. Whites of middling or lower status may have felt abandoned and racially vulnerable as a result, but the demand for residential segregation rose only as the drive for black disenfranchisement collapsed. There may have been something in Bruce’s contention that African Americans’ access to the polls intensified white demands for racial separation.

City solicitor Poe hinted at a similar motive for segregation in the opinion he prepared for Mayor Mahool. He justified it as a measure for the preservation of public order among blacks and whites because “close association between them on a footing of absolute equality is utterly impossible . . . and invariably leads to irritation, friction, disorder, and strife.”50 Poe’s rationale seems one more instance in the city’s longstanding effort to prevent race from becoming a subject of political contention.