CIVIL SERVICE AND PROHIBITION

HAVING LOST THEIR BATTLE in the Maryland General Assembly, the opponents of annexation challenged expansion of Baltimore City in the courts, but the city’s possession of its former suburbs stood undisturbed. Mayor Preston was not so fortunate. Though originally elected as a Democratic warhorse, he had so scrambled the bonds of party during his long campaign of municipal imperialism that he had unraveled the political network on which he depended and sacrificed control of the grander city that he now governed. Republicans had won annexation for him, and their next step was to refashion the character of his city. A new city charter was submitted to the voters in November 1918. Its principal feature was civil service reform.

Under the home-rule amendment adopted in 1915, the city could amend its own charter.1 The mayor and city council could begin the process of revision by nominating a charter commission for voters’ approval. But the amendment also allowed Baltimore’s citizens to place a charter commission on the ballot by petition of 10,000 registered voters. A committee of the City-Wide Congress collected the requisite number of signatures. The commission nominated by the congress included William J. Ogden, former city solicitor Edgar Allan Poe, the president of the Merchants’ and Manufacturers’ Association, an assortment of respected judges and attorneys, medical and academic luminaries from Johns Hopkins University and Hospital, and portrait photographer David Bachrach—but no party politicians.2 The city’s voters put the commission to work on a new charter in November 1917. The home-rule amendment did not permit the commission to endow the municipal government with any powers beyond those granted by the state legislature, but within those limits it could amend the city charter without submitting the changes to the General Assembly.3

The central provision of the proposed charter created the City Service Commission to oversee the hiring and promotion of all city employees not appointed by the mayor and city council. Both political parties would be represented on the commission, and its members would classify all city jobs. For those in the “competitive class,” the commission would design a system of examinations.4

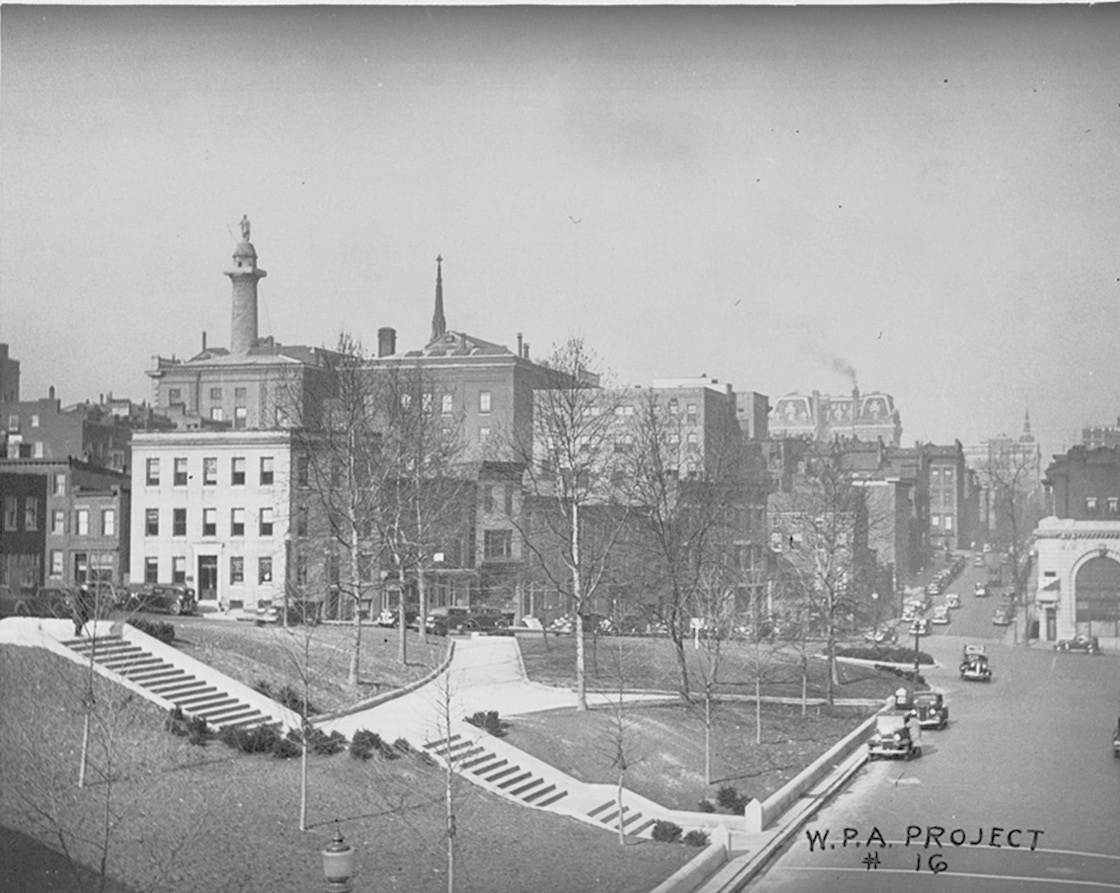

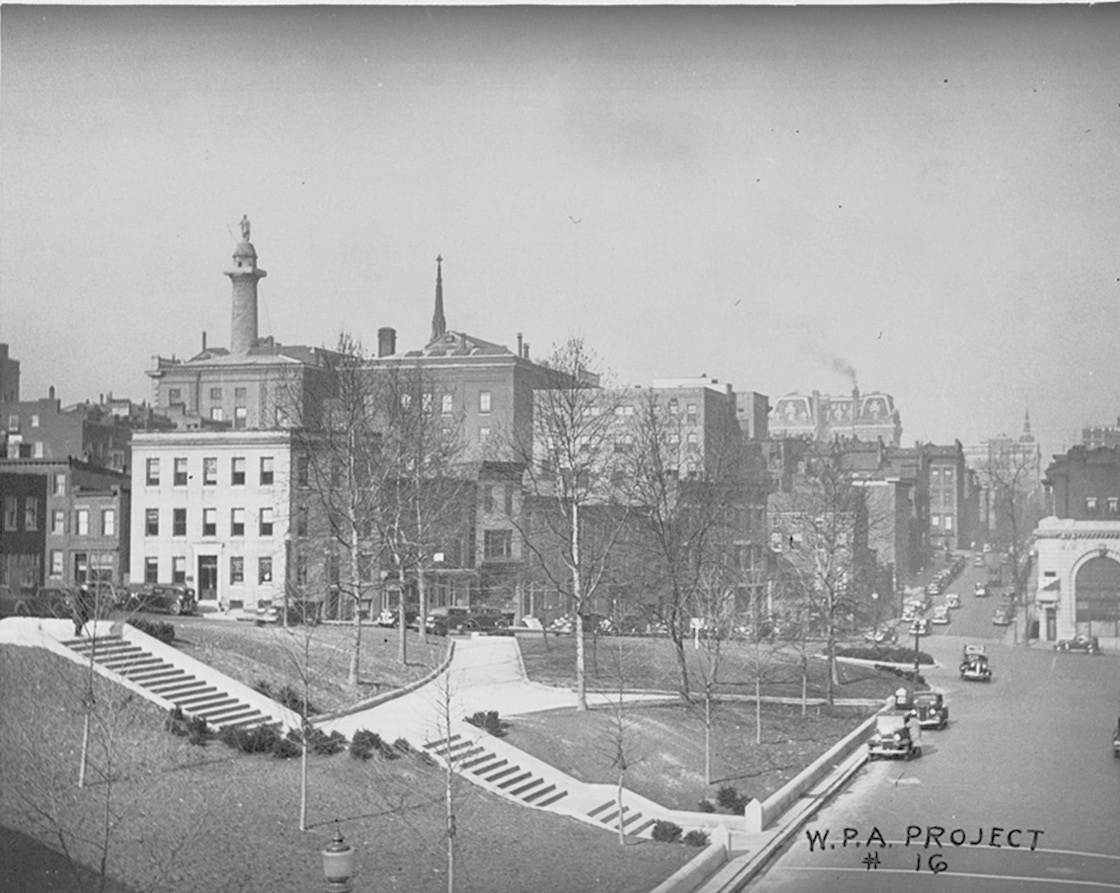

Preston Gardens, an early venture in slum clearance. Mayor Preston proposed it as a means to replace a concentration of African American housing in close proximity to the central business district and city hall. Courtesy Enoch Pratt Free Library

Baltimore’s Democratic and Republican organizations both opposed the new charter; its merit system might destroy the patronage system on which they fed. In fact, as Joseph Arnold observed, the merit system posed no great threat to the spoils system. The level of competence required for municipal employment was not beyond the reach of most party activists. Civil service regulations might, however, impede a new administration’s efforts to rid itself of an old administration’s appointees. Sonny Mahon later complained about the difficulty of sustaining his political organization with “a law that keeps a lot of Republicans in office after you win an election . . . The people don’t want that. That isn’t what they vote for, and it’s against all principles of our government.”5

Frank Furst found little that was objectionable about the new charter. He abandoned his Democratic friends and supported it. The voters did the same, approving the new charter by more than three to one. It carried all but one of the city’s wards.6

DEMOCRATIC DOWNFALL

In April 1919, Mayor Preston wrote to architect Thomas Hastings in New York, urging him to complete his comprehensive plan for the city. Among other projects, Hastings designed a widening of St. Paul Street that included a park and a sunken garden, just blocks from city hall and the courthouse. The new development replaced a neighborhood of black Baltimoreans that threatened to envelop the city center and surround the seat of municipal government. Preston described the area as “stagnant and out of touch with its vicinity.” He ordered the homes to be leveled—an early exercise in slum clearance. The civic amenities that replaced them would eventually be known as Preston Gardens. Preston wanted his plan for the city as a whole to take effect as soon as possible. His letter to Hastings explained why. “We had bad luck last week, and we will have a new Mayor down here about the first of May.”7

Preston had not even been able to get past the Democratic primary. He had lost by 4,000 votes, and once again it was his struggle to achieve annexation that helped to defeat him. The residents of the newly annexed territory voted solidly against him and, according to the Baltimore Sun, his opponent in the primary enjoyed the backing of the state Democratic organization, which had fought Preston on the issue of annexation. Yet the hostile Sun had been moved to enhance its estimate of the mayor in spite of his ties to the Mahon machine. Preston sent his last annual message to the city council in the autumn of 1918. Without abandoning its animosities toward the Ring, the Sun paused to pay him a kind of tribute. It expressed “a certain measure of respect for the turbulent genius” whose “record of achievement . . . evidences very clearly that the present boss of City Hall is really the boss.”8

Preston’s Democratic challenger was George Weems Williams, who enjoyed not just the backing of the state party organization but the support of Frank Kelly and his local Democratic insurgency. Williams was a Baltimore aristocrat and one of the city’s leading attorneys. His family owned a steamboat company, and he was educated in private schools and at Princeton. His campaign for mayor was his first and only descent into electoral politics. Though he prevailed in the Democratic primary, he came up short in the general election against Republican William F. Broening.

Broening was no aristocrat. He grew up in South Baltimore’s Fifteenth Ward, one of 10 children of German immigrant parents. His father was a tailor, and Broening left public school after the primary grades to add to the family’s income. His first job was in the office of a company that made and sold stoves. He later became an apprentice in its manufacturing operation and for four years learned to be a sheet-iron worker and coppersmith. In the evenings after work he would read law books; he eventually left the stove factory for the University of Maryland Law School, graduating in 1897 at the age of 27. In the same year, the Fifteenth Ward elected Broening to the first branch of the city council, as a Republican. One of his early accomplishments as a councilman was an ordinance establishing a municipal “subway” system. It carried no passengers but provided a network of conduits beneath the streets that carried electrical, telegraph, and telephone lines, reducing the need for aboveground wires and utility poles. The rental fees for space in the conduits became a significant source of municipal revenue.9

Broening left the city council after one term to serve in the house of delegates for one term, then became secretary to Republican congressman George Wachter, and in 1911 he won the first of two terms as state’s attorney of Baltimore. In the Republican mayoral primary of 1919, he faced no opposition. He portrayed his Democratic opponent as the agent of the state party organization and warned that election of the Democrat might strengthen the state’s hand in the management of Baltimore’s affairs. Williams, according to Broening, was also the creature of corporate power. As an attorney, he had represented railroads that laid claim to city streets and petitioned the municipality to provide space for sidings and terminals.10

A Sun columnist suggested that Broening lacked an independent program and that he conducted his campaign by matching the moves of his opponent: “If Mr. Williams offers the people an issue today, does Mr. Broening bite his fingernails and walk the floor, and finally decide to tell the people there is nothing in that? Not at all! Not at all! He calmly steps to the front the next day or the day after that, and tells the people the same thing Mr. Williams had told them before . . . What is more William F. Broening has his fingers in the armholes of his waistcoat and his face plainly shows that he is saying to himself: ‘Come on, you George Weems Williams! Come on and try to say something I cannot repeat! Dare you, dare you, dare you.’ ”11

Broening began his campaign with an appreciation of Mayor Preston’s record. Preston’s “sole thought,” he said, was “in developing Baltimore, and through his aggressive efforts he has pushed to a successful conclusion many improvements begun under his predecessors, and initiated others.” His “great outstanding achievement,” of course, was expansion of Baltimore by annexation, which he accomplished only with Republican support.12

It was politically convenient for Republicans to praise Preston and his record. In the Democratic primary, Williams had run against the mayor’s record. Exalting Preston diminished Williams. And Preston’s record was substantial. In addition to annexation, Preston could claim much of the credit for founding the Baltimore Symphony Orchestra and almost all the credit for construction of the municipal auditorium and War Memorial Plaza, which stretched out in front of the auditorium, styled by some civic boosters as Baltimore’s own Place Vendôme. He also played an early role in creation of the Baltimore Museum of Art. He buried the troublesome Jones Falls under a new thoroughfare, the Fallsway, and wrapped another major artery, Key Highway, around the base of Federal Hill and across Locust Point. Former Republican mayor Timanus went so far as to deplore the defeat of Preston in the Democratic primary. It is unlikely, however, that the Republicans would have preferred to face Preston in the general election. Their embrace of the defeated mayor seemed calculated to win over the Democrats who backed Preston in the primary.13

Democratic city councilman William Purnell Hall, like the Sun, noted Broening’s tendency to echo the positions of his opponent and characterized his campaign as “silly.” Hall observed that during his two terms as state’s attorney, Broening had never tried a case on his own. The Sun seemed to agree with Hall’s assessment when it noted that Broening was “never thought of as an able man.”14 He seemed a step down in political stature from Mayor Preston.

Broening’s victory was a surprise. Even his fellow Republicans had not expected it. The day before the election, the betting odds had run two to one against him. But his success was decisive. He led Williams by almost 10,000 votes of a total of 111,000, one of the heaviest turnouts in the town’s history. The Sun pronounced it “the most remarkable of any election held in Baltimore in a generation,” but could not account for its outcome. The paper could only surmise that voters favored Broening because he “worked his way to the front from humble origins.” At the time of Broening’s death, in 1953, the Sun would recall that he was “certainly not the liveliest mayor.” His two terms in office were “placid, even sluggish,” but he was “the best-loved of Baltimore mayors” in the twentieth century. “Everyone liked him.”15

Heavy turnout among black voters certainly contributed to Broening’s triumph, though it may not fully explain the election’s outcome. Black Republican candidates won two seats in the first branch of the city council, more than at any previous election. Broening won both of these council districts by margins greater than expected.16 Yet he seems to have done little to attract black voters. The Democrats, however, did much to alienate them.

Albert Ritchie, Maryland’s Democratic attorney general, delivered a speech in Baltimore warning white voters that “if Mr. Broening is elected Mayor, not only will negroes be appointed as laborers and in other branches of the city service, but because of the merit system, which goes into effect on January 1, 1920, it may be perfectly possible for them to stay there indefinitely.”17 Mayor Preston did even more to turn away black voters. Long before the Afro-American criticized Preston for leveling black housing to make way for Preston Gardens, it called attention to his conduct at the commencement exercises of the city’s black high school, where he handed out diplomas but avoided shaking hands with the graduates. Finally, one young woman managed to slip her hand into Preston’s; the black audience erupted in applause. During his campaign for reelection in 1919, while addressing an audience of ship caulkers, Preston had asked those who supported his reelection to raise their hands. When he noticed that some black workers had raised theirs, he added that he was speaking only to the white men. A full year before the election campaign began, the Afro announced that “eight years of Preston’s ‘lily white’ government is enough,” and before there were any other candidates to support, the paper decided that it wanted “NO MORE PRESTON.”18

Mayor Broening may have regarded his black support as more burden than bonus. In 1922, he would erase the impression that he was the favorite of Baltimore’s black voters. Against the protests of black clergymen, he authorized a Ku Klux Klan parade through the city.19

THE CIVIC AGENDA

Mayor Preston managed to unveil his comprehensive plan for the city and its newly annexed territory just before the inauguration of his successor. It was a close thing. A box carrying the final map of the future city, though nine feet long, had somehow gone astray in the mail between the New York architects and Preston’s city plan commission. He was able to publish the commission report with maps and drawings just before he left office.20 Mayor Broening’s inaugural address held little beyond Preston’s plans. Broening acknowledged as much. He embraced the “program in physical and industrial upbuilding which has given Baltimore a new place among the cities of our country, and . . . cheerfully [accorded] credit in competent leadership for the success already achieved.”21

Broening’s principal task was to raise the money to pay for all the projects he had inherited. He mobilized the municipal elite and the local press in a vigorous campaign to win voter approval for four bond issues. One would generate funds to build new schools and renovate old ones—an agenda item borrowed from George Weems Williams. Another was to finance an expansion of the city’s water supply and extend water service to the newly annexed parts of the city. A third was for the harbor improvements that had been a focus of Preston’s annexation initiative and a major subject in his comprehensive plan for the city. The fourth was to pay for extension of essential public services in the new annex. A sharp increase in the property tax rate was predicted if the loans were not approved. Democrats Frank Furst and James Preston endorsed the city loans. A parade of 10,000 adults and schoolchildren marched in support of the bonds. Local movie theaters showed a film in silent support. A general executive committee of almost 200 prominent Baltimoreans stood behind the loan proposal. The strenuous promotional campaign seems to have worked—or perhaps it had been unnecessary. Voters approved the four loans overwhelmingly. The harbor loan, for example, passed with more than 95 percent of the vote.22

On another matter, however, the city failed to win a vote of confidence. A ballot question asked whether Baltimore’s police department should continue under the control of the governor or whether authority over the department should be transferred to the mayor. A majority of 54 percent indicated a preference for the governor, affirming an arrangement made familiar by almost 60 years of experience.23

Broening’s administration brought a change of party in the mayor’s office but few other changes. Facing heavy Democratic majorities in both branches of the city council, Broening would probably have won little support for initiatives of his own. The mayor did appoint a committee to consider combining the council’s two branches into a unicameral body of 18 members, 3 members to be elected from each of six districts. The city charter was amended accordingly, and the council’s Democratic majority became even more lopsided.24

The mayor’s municipal construction campaign encountered at least one serious snag. The Allied Building Trades Council objected to the employment of nonunion labor on some of the city’s projects, and its members at work on those sites walked off the job in June 1921. A year later, a city council member from Southeast Baltimore (a “Kelly Democrat”) reignited the city’s labor troubles when he introduced an ordinance defining the wage rates to be paid on city construction projects. Existing legislation called for workers to receive the “current rate of per diem wages.” The proposed ordinance would have defined the “current rate” as “the wages paid by any recognized organization of workingmen”—in other words, the union rate. The proposal generated controversy both inside the council and out. The council rejected the proposal decisively. Edward Bieretz, business agent of the Allied Building Trades Council, announced that “labor must get into politics.”25

BREWING STORM

The national Prohibition amendment (Eighteenth Amendment) became effective on January 17, 1920. By early March, Mayor Broening was in Annapolis leading a Baltimore-based assault on the law, demanding that the General Assembly rescind its ratification of the amendment and that Maryland challenge Prohibition before the US Supreme Court. Noting that the amendment allowed the states “concurrent power” with the federal government in enforcement of Prohibition, Broening also argued (implausibly) that Maryland should exercise this power by declaring the Volstead Act void within its boundaries.26

The country had already been legally dry for six months before Prohibition, under the provisions of the Wartime Prohibition Act, perversely approved by Congress a week after Armistice Day and then passed over President Wilson’s veto. It was justified as a measure to conserve foodstuffs for the war effort, especially grains used in the brewing of beer and distillation of liquor. Baltimore, however, remained moister than most towns. One Prohibition agent later described the city as “dripping wet.” The characterization came in his letter of resignation, which also complained about the difficulties that Baltimore posed for making arrests and securing convictions under the Volstead Act.27

William H. Anderson, the Anti-Saloon League’s superintendent for Maryland, had detected the city’s distinct hostility to his organization’s cause.28 In 1916, after Anderson had left Maryland, the league and its allies seemed close to victory. A bill requiring the state’s remaining “wet” counties and Baltimore to vote on Prohibition had been introduced in the house of delegates. Lopsided overrepresentation of dry, rural counties in the General Assembly made it likely that the measure would pass. Four delegates from Baltimore—three Democrats and a Republican—submitted a plea that Baltimore be exempt from the law. Prohibition, they argued, never worked in big cities. Its enforcement would cost Baltimore tax revenues and liquor license fees and would destroy the jobs of residents who worked in the city’s breweries, distilleries, and bars. But the bill passed as written.29

The Baltimore delegates need not have worried. Not a single one of the city’s 24 wards voted dry. In the ethnic neighborhoods of Southeast Baltimore, the margins of defeat were staggering. On the city’s southeast fringe, the First Ward voted 97.7 percent wet. In the city at large, nearly three-fourths of the voters cast their ballots against Prohibition.30

When the General Assembly considered ratification of the Eighteenth Amendment in 1918, the House Temperance Committee recommended that the legislature delay its vote until the next session so that a state referendum could determine where Maryland’s voters stood on Prohibition. But the drys had learned their lesson two years earlier. Baltimore, with half the state’s population, would dominate any popular vote on drying up Maryland, and the city’s electorate had left no doubt about its position on Prohibition. The General Assembly chose not to consult the voters and ratified the Eighteenth Amendment. Only two of Baltimore’s 23 representatives in the house of delegates voted in favor of it.31

Dry legislators soon had second thoughts. Republican state senators from dry counties on the Eastern Short introduced a bill that urged Congress to legalize 3.5 percent beer. They had not anticipated that Congress would define “intoxicating beverages” as those with alcohol levels of more than 0.5 percent. For Baltimore’s beer-drinking German population, the restriction came as a shock. Many had expected that the Volstead Act would outlaw only distilled spirits. Even for Maryland drys, Prohibition seemed more drastic than anticipated. Sharp turnover in the membership of the General Assembly in 1918 may also have contributed to a change in the legislature’s stand on alcohol.32

The shift in mood may explain why Maryland was the only state that never enacted legislation to support enforcement of the Volstead Act. For this distinction Maryland earned its title as the “Free State,” bestowed in 1922 by Sun editor Hamilton Owens. Governor Albert Ritchie embodied Maryland’s resistance to Prohibition. Ritchie objected to the cost of its enforcement and to its imposition on Maryland without a popular vote, but above all he regarded it as an “encroachment of Federal power upon the functions of the States.” It was one of many such encroachments. “Just now,” he added, “it holds the stage and holds it so prominently as to obscure the fact it is simply one phase of the only question of principle upon which the American people can with consistency divide politically today.”33 Ritchie opposed Prohibition because he was a principled advocate of states’ rights.

Many Baltimoreans needed no principle. They simply ignored federal encroachment. Restaurants carried signs bearing red crabs to signal customers that they sold beer. The Belvedere Hotel’s Owl Bar used its iconic bird to notify patrons about the availability of alcohol. If both of the owl’s eyes were illuminated, only fruit juices and soft drinks were on sale, but when the owl winked, there was booze. Organized crime of the kind that bloodied Chicago and Detroit never took hold in Baltimore. It was unnecessary. Baltimoreans could get drunk without much in the way of organized criminal conspiracy.34

Illegal alcohol production was a major local industry. In March 1922, federal agents raided a moonshine plant on East Pratt Street that was alleged to produce 300 gallons of liquor a day. At the time, it was thought to be the largest bootlegging operation in the United States. But then, just two months later, agents raided a building on East Street and found 22 stills and 3,500 gallons of mash. Even some ostensibly legitimate businesses found it difficult to resist the profitable possibilities of Prohibition. The US Industrial Alcohol Corporation produced alcohol for industrial and medicinal uses at its waterfront plant in Curtis Bay. Both kinds of spirits were legal under the Volstead Act, but the company modified its industrial alcohol to make it nonlethal and drinkable. A gallon of its 185 proof product sold for about three dollars. After diluting it with a gallon of water and adding glycerine for flavor, a bottle of the concoction could be rolled on the floor with one’s foot to mix the contents, aged for half an hour, and then consumed as “gin.” The company’s waterfront location made it easy to export immense quantities of its bootleg output by ship, though it also used Baltimore’s railroad facilities. Prohibition agents found a car carrying 8,000 gallons of Industrial Alcohol product at the President Street Station. It was labeled “olive oil.”35

In addition to their defiance of Prohibition, some Baltimoreans fought to bring about its repeal. There was, of course, the “ombibulous” H. L. Mencken, who drank beer for breakfast. One of Mencken’s less voluble friends was William H. Stayton, president of the Baltimore Steamship Company and, in 1918, founder of the Association Against the Prohibition Amendment. Stayton came to the city from his native Delaware by way of the Naval Academy, achieving the rank of captain. He retained the title for the rest of his life. Captain Stayton’s objections to Prohibition had much in common with Governor Ritchie’s. He thought that the regulation of alcohol was the business of state and local governments and no concern of federal authorities. His organization quickly attracted a national membership of 30,000, including about 1,000 Baltimoreans, one of whom was Frank Furst. Beyond Baltimore, Stayton’s organization enlisted Kermit Roosevelt, Vincent Astor, and John Philip Sousa.36

By 1926, the association claimed 726,000 members nationwide. But Stayton had begun to concentrate less on mass recruitment and more on enlisting “quality” members, wealthy men who could finance the association’s political campaigns against dry candidates. They included Marshall Field, Pierre DuPont, Stuyvesant Fish, and John J. Raskob of General Motors. The plutocrats shouldered Stayton aside. DuPont and Raskob, in particular, wanted to steer the campaign for repeal toward their objective of reducing the income tax. Federal taxes on alcohol, they hoped, would generate sufficient revenue to make the progressive income tax unnecessary or innocuous to people of their class.37

But Stayton was not overlooked when repeal was won and its grateful advocates named their heroes. Stayton’s friend Mencken was one such advocate. “The hero of the day is Capt. William H. Stayton,” he wrote, “organizer of the Association Against the Prohibition Amendment. He was bearing the heat and the burden at a time when nine-tenths of all the politicians were skulking. He has done the American people a vast service, and I only wish that I could hope that they will not forget it.”38 Unlike Mencken, Stayton was a teetotaler, and his next public project after repeal was to devise systems of alcohol regulation for the nation’s states.39

Other Baltimoreans joined the crusade along with Stayton. In 1924, US Senator William Cabell Bruce, former Baltimore city solicitor, advocated repeal of the Volstead Act, though not revocation of the Prohibition amendment itself. He was, at this point, only a “modificationist” who wanted to allow each state to impose its own regulations for the sale and consumption of alcohol, subject only to the provisions of the Eighteenth Amendment itself. Two years later, Bruce’s position had evolved, and while he did not explicitly advocate repeal, a major change in the Prohibition amendment seemed to follow from his argument. He advocated adoption of the “Quebec System,” under which the provincial government operated a government liquor monopoly. Wine and beer would be sold by licensed restaurants, hotels, and grocery stores, but only state governments could sell distilled spirits.40

Senator Bruce laid out his position in a lengthy treatise delivered before a subcommittee of the Senate Judiciary Committee—35 years after his treatise The Negro Problem.41 He had since taken to attacking the Ku Klux Klan of Alabama for its lawlessness. Senator Hugo Black of Alabama reciprocated by condemning Maryland’s lawlessness with regard to the Volstead Act.42 Lawlessness was one of Bruce’s principal concerns about Prohibition. It made outlaws of thousands of imbibing Americans, created a class of gangster bootleggers, and opened opportunities for bribery and corruption among Prohibition agents, who were not covered by civil service regulations. Bruce’s objections to Prohibition were largely practical, not principled like Albert Ritchie’s, though they led him to support Ritchie’s preference for state regulation.

Congressman John Philip Hill of Baltimore was a more flamboyant warrior for the wets. He delighted in publicity. Time Magazine claimed that “if newspapers were abolished, he would curl up and die.” One of his first pitches for the headlines was a bill proposing that the House finance a veterans’ bonus by taxing beer and light wines, which would obviously require an overhaul of the Volstead Act. Baltimore’s city council passed a resolution supporting his bill, which was defeated, but got Hill into the New York Times.43

Hill next attacked the disparity in Prohibition’s treatment of farmers and city folk. Farmers could legally produce hard cider, an indulgence denied to urbanites. Hill renamed his house on West Franklin Street “Franklin Farms,” had a picture of a cow painted on his fence, and planted apple saplings and grape vines. He pressed fruit (probably purchased elsewhere) and entombed their juices in his basement. Their fermentation, he claimed, was not his responsibility. The apples and grapes, not Hill, violated the Volstead Act. He regularly invited Prohibition agents to measure the alcohol content of the wine and cider maturing in his cellar. He wanted to compel the federal government to specify just what levels of alcohol were permissible for homebrew under the Volstead Act, even if he got arrested in the process. He did. But a jury decided that his concoctions were not intoxicating, even though they exceeded 12 percent alcohol by volume. And federal district judge Morris Soper decided that Hill’s homebrew was not covered by the Volstead Act’s 0.5 percent limit for beverages commercially manufactured and sold.44

Hill, Stayton, Ritchie, and Bruce agreed that the regulation of alcohol was a state or local matter. While all four did not elevate the issue to the principled altitude attained by Ritchie, they reflected a general sentiment that it was not the federal government’s business to tell people what they could drink. They shared their partiality for states’ rights with many southern Democrats. But most southern Democrats did not share Maryland’s openness to alcohol. Southern fundamentalists disapproved of strong drink. But the conjunction of southern sentiments on states’ rights and northern drinking habits made Baltimore one of the wettest cities in the country.