RACIAL BREAKDOWN

MAYOR MCKELDIN’S ENDORSEMENT of a one-time Republican congressional candidate failed to avert intraparty factionalism in the mayoral contest of 1967. A former Republican state legislator challenged McKeldin’s choice. Both men appealed for black votes. But Democratic city council president Thomas D’Alesandro III was generally recognized as the heir apparent.

A former city council member, Peter Angelos, was D’Alesandro’s principal challenger in the Democratic primary. The Angelos ticket included an African American for city council president—state senator Clarence Mitchell III. His counterpart on the D’Alesandro ticket was council member William Donald Schaefer. Mitchell’s West Baltimore political rival, state senator Verda Welcome, endorsed the D’Alesandro ticket.1

As in previous municipal elections, bossism emerged as the principal focus of the campaign. Peter Angelos announced his candidacy with an attack clearly aimed at D’Alesandro: “We can no longer endure elected officials born in bondage to political factions and whose sole concern is their selfish interest rather than the needs and hopes of a million people.” Hyman Pressman, candidate for city comptroller on the D’Alesandro ticket, responded in kind. Jack Pollack, he charged, “was the architect of the Angelos ticket.” Francis Valle, who ran with Angelos as candidate for comptroller, had long been associated with the Fourth District boss. Angelos not only denied any connection with Pollack but said that his ticket would reject any support that the infamous boss might offer. Pollack issued a press release: “I have followed closely the childish efforts of Peter Angelos and Hyman Pressman to stir interest in their lagging campaigns by using me as a whipping boy.” The release ended by announcing that “I have no interest in the campaign.” In his own handwriting Pollack added, “at this time.”2

Beneath the talk about bossism lay the more seismic issue of race. D’Alesandro walked into a meeting of the all-white Young Men’s Bohemian Democratic Club just as a speaker declared, “We’ve got the guts to stand up for you—the white people.” When D’Alesandro stood up to speak, he said, “What we want and need is a guarantee all men can live in peace and dignity—I hope you can agree.” Later in the campaign, he rejected the endorsement of the National States Rights Party “with distaste and disgust” for “its philosophy of bigotry.”3 Mayor McKeldin defended D’Alesandro against Republican attacks questioning his commitment to racial equality. As city council president, D’Alesandro had been the chief sponsor of McKeldin’s failed open-housing ordinance. But Baltimore’s black electorate leaned toward the Angelos ticket, possibly because it included a black candidate for council president. Schaefer won the primary, but lost every black precinct to his African American opponent, Clarence Mitchell III. Though his victory over Angelos was overwhelming, D’Alesandro nevertheless trailed him in most black neighborhoods.4

D’Alesandro and his ticket outpolled their Republican opponents by approximately 110,000 votes, and the city council that took office with D’Alesandro was entirely Democratic. Four of its 18 members were African Americans, up from two in the outgoing council. In his inaugural address, the new mayor promised to “root out every cause or vestige of discrimination.” One of his first official acts was the appointment of a new city solicitor. He chose George Russell, who had been the first African American judge of the Superior Court. The mayor announced that he would propose new ordinances to outlaw discrimination in housing and public accommodations and would establish neighborhood “mayor’s stations” where citizens could file complaints and make inquiries about city programs. There would also be neighborhood development corporations and neighborhood centers where public and private agencies would offer a range of services.5

The Afro-American saw D’Alesandro stepping up to the mayor’s office in a “mean Baltimore”—“a time when civil unrest is extremely high in this city.”6 After the eruptions in Harlem and Watts, race riots had wracked Newark, Detroit, Chicago, and Cleveland. Baltimoreans seemed torn between self-congratulation for having avoided collective violence and apprehension that it might break out at any time. D’Alesandro did what he could to avert the explosion. Just two months after his inauguration, he opened the first of the mayor’s stations. He compromised with black militants who demanded control of the local Model Cities program. He asked leaders of public and private agencies to plan for “a coordinated fully programmed summer” for the city’s young people. He submitted bills to the General Assembly that would eliminate all exceptions from the open-housing and public accommodations statutes. He met with the members of the Greater Baltimore Committee to urge that they create jobs for the city’s unemployed.7

He also recommended measures aimed more directly at the prevention of civil disorder. A new loitering ordinance was introduced in the city council. It was designed to disperse street-corner congregations of young people after dark, an echo of similar concerns voiced a century earlier. But six prominent black leaders issued a statement suggesting that this measure and other crime-fighting initiatives were aimed at African Americans, noting that they emerged in the aftermath of “ghetto rebellions.” “The coincidence of these phenomena,” they charged, “suggest[s] that the real concern is for the property and persons of whites rather than the blacks who ostensibly are to benefit most by the proposed measures.” The Sun raised the possibility that enforcement of the proposed anti-loitering ordinance might become the “potential spark” igniting the riot that the measure was supposed to prevent. A month later, the mayor directed city council president Schaefer to cancel hearings on the loitering bill, and a “high city official” predicted that the proposal would die in committee, adding that “it was a potential source of trouble, that bill.” The mayor said that it was “just not the right time.”8

DIVIDING HIGHWAY

Like Theodore McKeldin, Thomas D’Alesandro III arrived in the mayor’s office to face an unfinished and controversial expressway. D’Alesandro’s road project, however, was much less finished and more controversial. It was the East-West Expressway first proposed by a team of engineers in 1942, though such crosstown transportation ventures had antecedents dating to the eighteenth century.9 By the time D’Alesandro took office in 1967, the original plan for the freeway had been followed by nine more. In 1944, the city had brought the imperious Robert Moses from New York as a consultant, with the hope that he might envision a highway that would command sufficient reverence to reach the construction stage. He proposed an east-west route that would displace 19,000 residents, most of them black and living in slums. The elimination of their neighborhoods was one of his plan’s selling points. According to Moses, “the more of [these neighborhoods] that are wiped out, the healthier Baltimore will be in the long run.” The Baltimore Association of Commerce saw similar benefits in expressway construction. Freeways were the means by which the central business district might be “rescued and redeemed” because they “would pass through blighted areas” or “sections approaching blighted conditions.”10

Moses estimated that his east-west highway would cost the city about $40 million. Attorney Herbert M. Brune charged that the real cost would be much higher. Brune served on a mayoral committee created to study the problem of traffic congestion in Baltimore. Moses’s cost estimate, he noted, omitted the expenditures needed to replace the five schools and 12 churches that would be demolished if his highway were built. There was also the cost of housing the 19,000 people that the expressway would displace. Brune concluded “that the carrying out of this project will be disastrous for the city of Baltimore, socially, financially, and from the standpoint of well-rounded traffic improvement.” H. L. Mencken was more concise. He predicted that Moses’s expressway would be approved because “it has everything in its favor, including the fact that it is a completely idiotic undertaking.”11

The city council rejected the Moses plan, not because it was idiotic, but because even at $40 million it was too expensive for the municipal budget. But the Federal Highway Act of 1956 changed the way freeway builders counted their costs. Expressways that complied with federal specifications and connected with the interstate highway system could qualify for federal funds covering up to 90 percent of the outlay for condemnation, clearance, and construction. By 1957, the Baltimore City Planning Commission had come up with a complex expressway proposal to take advantage of federal funding. Its chief components were an east-west freeway that intersected a north-south freeway—the Jones Falls Expressway (I-83), which would extend southward on a bridge across the Inner Harbor, over or around Federal Hill, and then continue as the so-called Southwest Expressway. The plan also included an inner beltway that circled the central business district, which would sprout a Southeast Expressway passing through Fell’s Point and Canton, tying the central business district to much of the city’s heavy industry. Yet another highway (I-95) would approach the city from the south and cross the harbor from Locust Point to Southeast Baltimore by means of a tunnel, then continue northward to connect with both the East-West Expressway and the Southeast Expressway. Both I-95 and I-83 were to make connections with the Baltimore County Beltway, then under construction.12

Completed in 1962, the Beltway circled the city and linked its various suburbs to one another, enhancing their collective autonomy from the city. That, at least, was the threat that Baltimore’s highway planners perceived in it. Philip Darling, director of the planning department, likened the potential economic impact of the Beltway to that of the Erie Canal in the 1820s. It imperiled the city economy. Much as Baltimoreans of the 1820s found salvation in railroads, those of the 1950s would save their city from decline by building freeways that sent taproots out to the Beltway and beyond the city limits. The Jones Falls Expressway made one of these connections to the north; I-95 made another to the south. The proposed East-West Expressway would not only speed the flow of traffic through Baltimore but connect the city center with the Beltway’s suburban traffic on both the east and west. Like Darling, the Committee for Downtown claimed that the East-West Expressway would “lend a powerful force toward restraining decentralization.” It was part of a more general strategy “to revitalize the city now endangered by shopping malls and suburban growth along the outer beltway.”13

The planning commission’s 1957 plan competed with two other versions of the East-West Expressway. One emerged from a regional planning agency and another from an engineering firm hired by the Maryland State Roads Commission. The city hired three more engineering firms—known as the “Expressway Consultants”—to combine the plans into a single, revised standard edition. They had scarcely begun their work when the planning commission proposal ran into trouble in both Washington and Baltimore. Federal highway authorities objected to the steepness of the grade required to make the connection between a depressed section of the planned highway along Biddle Street and the elevated Jones Falls Expressway. The planning department adjusted the plan so that the depressed section on Biddle Street became elevated—and almost immediately ran into the determined opposition of the nearby Mount Vernon Neighborhood Association, whose upper-crust constituency included some of the most influential residents of the city. The organization’s president referred to the elevated section of highway as a “monstrosity.” Darling and his staff shifted their highway’s route south to Pratt Street, along the waterfront and beyond the range of these attacks. The southern route had an additional advantage: it would require the demolition of only a third as many houses as the Biddle Street alternative. The planners would achieve this reduction by building a portion of their expressway over the wharves along the margin of the Inner Harbor.14

In the meantime, the Expressway Consultants conceived an east-west route, labeled 10D, that ran even further south than the planning department’s proposal. It stayed south of the Inner Harbor until it reached Federal Hill, where it crossed the harbor on a 14-lane bridge, then traveled east through Fell’s Point and Canton. This was the first of the two expressway plans to receive a public hearing. In late January 1962, about 1,300 people gathered in a high school auditorium to shout down and heckle city officials and business executives who spoke in favor of the 10D route. Four members of the city council attended—all of them opposed. One managed to seize the microphone from the president of the Junior Chamber of Commerce, who, he charged, was a suburbanite. “About 15,000 are going to be put out on the street because of this expressway,” he shouted. “They are the people who ought to be heard, not those who live in the County.” The director of public works managed to wrestle the microphone away from the councilman, but the crowd yelled, “Let him talk!” One local businessman spoke against the expressway. He was Henry G. Parks, founder of the Parks Sausage Company, at the time the largest black-owned business in the United States. Parks, however, was present as the representative of the Baltimore Urban League. The Expressway Consultants, he said, had “put too much emphasis on engineering and not enough on human beings.”15 Little more than a year later, Parks would challenge one of Jack Pollack’s protégés to win a seat on the city council from West Baltimore’s Fourth District.

Mayor Thomas D’Alesandro III inherited the east-west mess a decade after the planning commission submitted its first plan. Though the city had acquired much of the property needed for the expressway, it had yet to pour its first batch of concrete. But the battle lines had hardened. A ground force of citizen organizations had mobilized to stop the road, notable for their acronyms as well as their militance: the Movement Against Destruction (MAD), the Relocation Action Movement (RAM), the Southeast Council Against the Road (SCAR), and Volunteers Opposed to the Leakin Park Expressway (VOLPE). John Volpe was the US secretary of transportation. The Society for the Preservation of Fell’s Point, Montgomery Street, and Federal Hill disdained acronyms but not protest.

Baltimore’s deadlock was not unusual. By the late 1960s, city residents across the country stood in angry opposition to the extension of urban freeways. But Baltimore’s road war seemed to stand out from the wider fracas. “Baltimore’s interstate history,” observes Raymond Mohl, “provides a fascinating case study of how not to build expressways.” Though the federal government stood ready to bestow hundreds of millions of dollars on cities that united behind expressway projects, Baltimore’s business and political elites seemed unable to come together on a single plan. Highway engineers differed with one another about expressway routing. The departments of planning and public works scarcely ever agreed. “Political infighting in Baltimore,” writes Mohl, “and between city and state muddied the waters for years.” Baltimore was distinctively “factious.”16

As city council president, the younger D’Alesandro had overseen the contentious process by which the council passed the condemnation ordinances to clear a route for the highway. It did so in modest steps, one segment at a time. D’Alesandro later recalled that “every condemnation ordinance was a real blood bath.” The public hearings verged on civil disorder. William Donald Schaefer, chairman of the council’s judiciary committee, presided over them. One session in 1965 got so far out of control that Schaefer simply walked out, declaring, “The hell with it all.”17

Municipal agencies expressed criticism of the expressway more decorously, but with just as much determination. By 1967, the chairman of the Baltimore City Planning Commission argued that the entire expressway plan needed revision, especially the southward extension of I-83 to Pratt Street. The Baltimore Park Board held up further extension across the Inner Harbor to Federal Hill. It alone had the authority to condemn parkland, and Federal Hill was a city park.18

DESIGN INTERVENTION

The federal Bureau of Public Roads attributed Baltimore’s stalled highway project to “city hall politics.” In an effort to sidestep further city hall complications, the federal highway bureau created a new agency, the Baltimore Interstate Division. Officially, it was a state agency, but most of its money came from the federal government, and its decisions were subject to the city government’s veto. It was to coordinate the design and construction of Baltimore’s expressways and mediate disputes between state and municipality under the general guidance of a policy advisory board chaired by the mayor. Both the federal highway agency and the Maryland State Roads Commission were concerned that the city might not be able to come up with an acceptable plan in time for the 1972 cutoff date for the funding of interstate highway projects.19 The chief obstacle was not the squabbling between city and state but public opposition.

Archibald Rogers, president of the city’s chapter of the American Institute of Architects, suggested a more comprehensive approach to expressway design that might address the concerns of neighborhood residents who stood in its path and ease the highway’s progress through the city.20 Rogers proposed that a team of architects, sociologists, engineers, and planners reexamine the expressway plan to see whether it might be refashioned to “reform and revitalize the city” so as to blend the highway into a better Baltimore. Rogers’s suggestion held the hope that the resistance of residents along the path of the road might be softened by ancillary projects and “joint development” ventures designed to enhance their neighborhoods and diminish the expressway’s intrusiveness. State highway officials were skeptical but willing to try almost anything to break the deadlocks. Federal highway officials were similarly inclined to support and finance an experiment in public pacification that might prove useful in overcoming the increasingly widespread opposition to urban freeways.21

The federal Bureau of Public Roads provided $4.8 million to sustain an Urban Design Concept Team (UDCT) for two years. The team’s job was to reconcile the city with the road. One of the team’s principal subgroups was spearheaded by missionaries from the San Francisco office of the Skidmore, Owings, and Merrill architectural firm (SOM). The team included not only architects but political scientists, sociologists, behavioral scientists, and urban planners. At the insistence of the State Roads Commission, a local engineering firm, the J. E. Greiner Company, joined the team in its reevaluation of the expressway plan. Greiner had received more than $20 million from the roads commission for helping to create that plan, and state highway officials evidently hoped that its participation in the review would prevent the UDCT from veering too far from the consensus the engineers had achieved. A further restriction on the team was the requirement that it could not depart from the route already plotted for the East-West Expressway and its offshoots. In addition, team participants were not to release any information to the public.22

These and other restrictions may have reflected changing currents in state politics. Republican Spiro T. Agnew was elected governor in 1966. He had close ties with Maryland’s engineering firms. Some of them had paid him kickbacks during his stint in Baltimore County government, and he appointed one of his confidants from those days, Jerome Wolff, to head the State Roads Commission. Wolff would later head a Greiner subsidiary, and later still would accept a plea bargain to testify at Agnew’s trial for extortion, conspiracy, and tax evasion. Bernard Werner, director of the Baltimore Department of Public Works, found in Wolff an ally to help him rein in SOM’s founding partner, Nathaniel Owings, who took charge of his firm’s outpost in Baltimore. Owings finally signed a memorandum of understanding, accepting the limits imposed on his firm’s work for the UDCT. He had no choice. The city council had approved the route laid out by the engineers with only one dissenting vote—Thomas Ward’s.23

Changes in national policy, however, may have strengthened Owings’s hand. The Federal Highway Act of 1962 called for state and local governments to develop “a cooperative, continuing urban transportation planning process.” Creation of the US Department of Transportation in 1966 placed a new level of supervision over the federal Bureau of Roads (now the Federal Highway Administration), and for the first time, the highway administrator, now Lowell Bridwell, was not an engineer.24

Conflict between the highway engineers and the UDCT caused such disruption and delay that the US Department of Transportation threatened to cut off the funds it had promised for the work of Owings’s team. Federal officials announced that the subsidy depended on resolution of the struggle between the engineers and the design team, and they saddled the state and the city with responsibility for achieving peace. The director of the Baltimore office of the US Bureau of Public Roads noted that the concept team’s role “as initially proposed by the State and the city [has] been changed in scope, responsibility, and output.” Owings later met with the secretary of transportation in an effort to clarify his team’s sphere of operation.25

Owings’s Washington visit infuriated Jerome Wolff and Bernard Werner. He had gone over their heads. Owings, said Werner, must “accept our dicta . . . or we don’t think he can properly be part of [expressway planning].” “We are his clients. If he can’t accept that fact, he won’t be our architect . . . Mr. Owings is not the one to go to the national level. We are. I don’t care if he knows Lady Bird or the President himself. It makes no difference to me.”26

In Baltimore, tension between Greiner and SOM led them to work separately. SOM would address the “urban design” issues; Greiner would then incorporate these modifications, when possible, into the highway plans. The arrangement freed SOM to work on its own with Baltimoreans fighting the expressway and to evade some of the restrictions under which it had agreed to operate. Its efforts did little to reconcile residents to the road. While meeting with citizen groups to find out what they wanted, team members from SOM “educated interested residents about highway engineering and planning” and provided them with “the technical knowledge they needed to effectively organize against the highway.”27

The Relocation Action Movement came together in 1966 at about the same time that state and federal officials were making arrangements for creation of the UDCT. RAM’s members and supporters lived in and around the Franklin-Mulberry corridor—a strip of real estate that extended west of the central business district. The corridor had figured in every proposal for an East-West Expressway going back to 1942. It would run through Rosemont, a stable, African American neighborhood where 72 percent of the residents owned their homes, and clip the southern edge of Harlem Park, the testing ground for Baltimore’s urban renewal, code enforcement, and rehabilitation programs. Relocation confronted the black residents of the two areas with the acute problem of finding new homes in a residentially segregated city where a rapidly growing population of African Americans was confined to already congested neighborhoods. Homeowners whose property had been condemned for the expressway could not expect compensation sufficient to purchase comparable housing. Under state regulations, they were entitled to their homes’ “market value,” but real estate that had lain under the shadow of condemnation for more than 20 years commanded little value in the market. Rosemont houses that had sold for $6,500 in 1948 brought only $4,000 in 1967.28

While forced to bear the disruption and displacement of expressway construction, black residents of Rosemont and Harlem Park were largely excluded from its benefits. RAM’s president, Joseph Wiles, complained that “this system . . . is being built for the convenience and exclusive use of white suburbanites to gain easy access to downtown districts.” The organization’s “Position Statement” was even more pointed: “For too long the history of Urban Renewal and Highway Clearance has been marked by repeated removal of black citizens. We have been asked to make sacrifice after sacrifice in the name of progress, and when progress has been achieved we find it marked ‘White Only . . . Unless black people’s demands are satisfied the Expressway WILL NOT be built.”29

But the expressway was already being built. The city had acquired most of the property needed to push the highway through the Franklin-Mulberry corridor, and demolition was under way. The cleared land lay vacant years before road construction would begin and created another set of inconveniences for remaining residents. The condition of the corridor’s housing deteriorated as property owners gave up on maintenance in anticipation of condemnation. In a 1967 petition to Mayor McKeldin, RAM demanded that the city “correct the negligent method of condemnation which often left one or two families on a block of vacated, boarded-up, garbage infested, city-owned housing causing increased problems of vandalism, rats, and an unreasonably large amount of additional upkeep on their own homes.” The Harlem Park Neighborhood Council warned that the vacant houses posed fire hazards. It proposed that the vacant land be used for playgrounds or other community amenities until it was covered with concrete.30

The Harlem Park Council had only positive things to say about the “team of sociologists, planners, architects, economists, acoustical experts, urban designers, landscape architects, and others” who gave “technical assistance to residents of the city.” The SOM wing of the UDCT had been meeting with neighbors of the Franklin-Mulberry corridor to identify interim uses of land cleared for the expressway. The team also got permission for a tentative departure from the policy that required them to work within the existing highway alignment. After being permitted to study alternatives to the Rosemont segment of the road, they identified three routes that circumvented the neighborhood, one of which the team members recommended unanimously. This alternative would cost less to build than the original alignment and would spare more houses, but it would have to slice through a cemetery, and under Maryland law cemeteries were not subject to condemnation. The restriction, however, did not apply to the federal government, the highway’s principal funding source. But the policy advisory board that oversaw the road project ruled that the cemetery was sacrosanct. Residents of Rosemont contended that dead white people were accorded more deference than live black ones.31

COMBAT IN THE STREETS

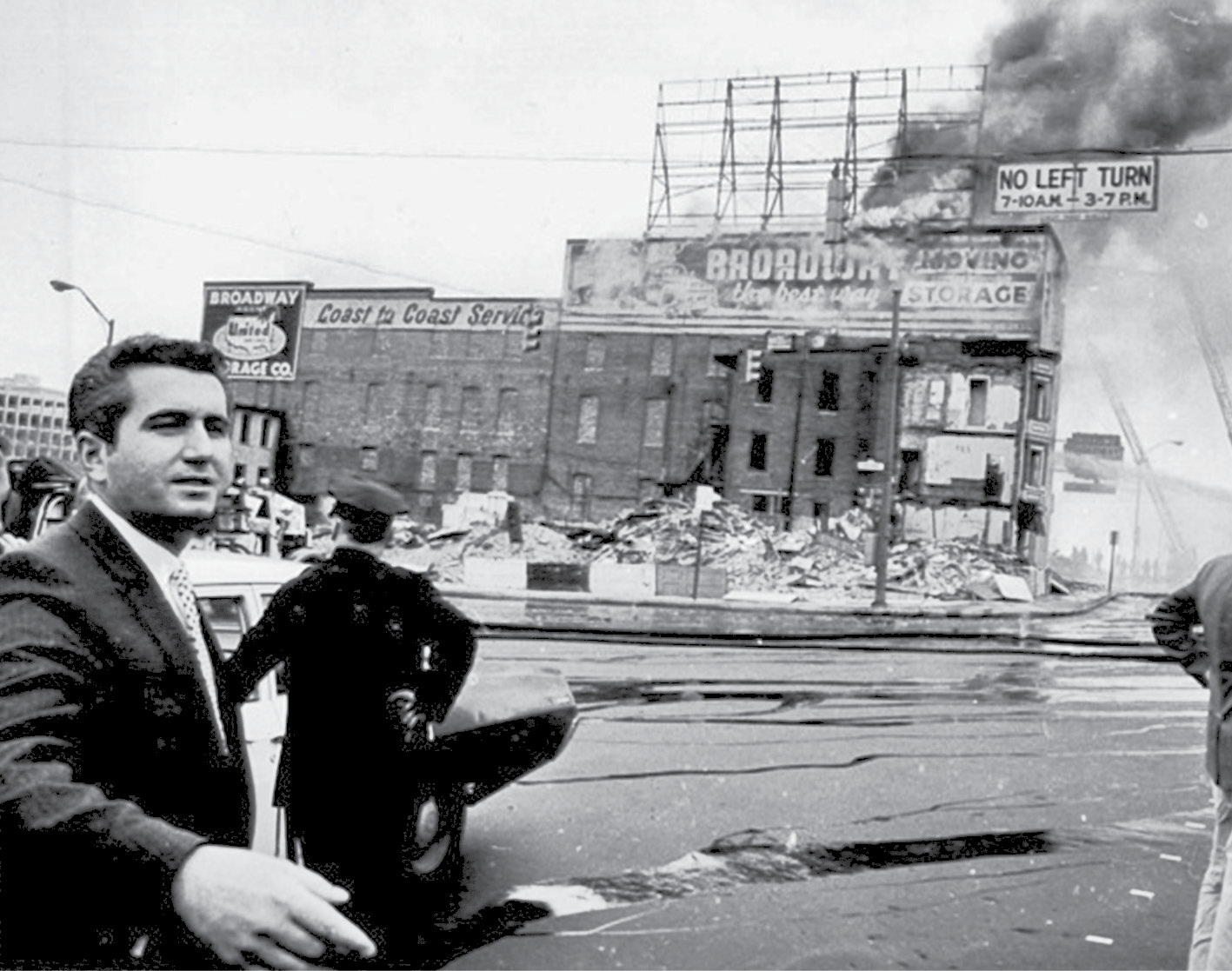

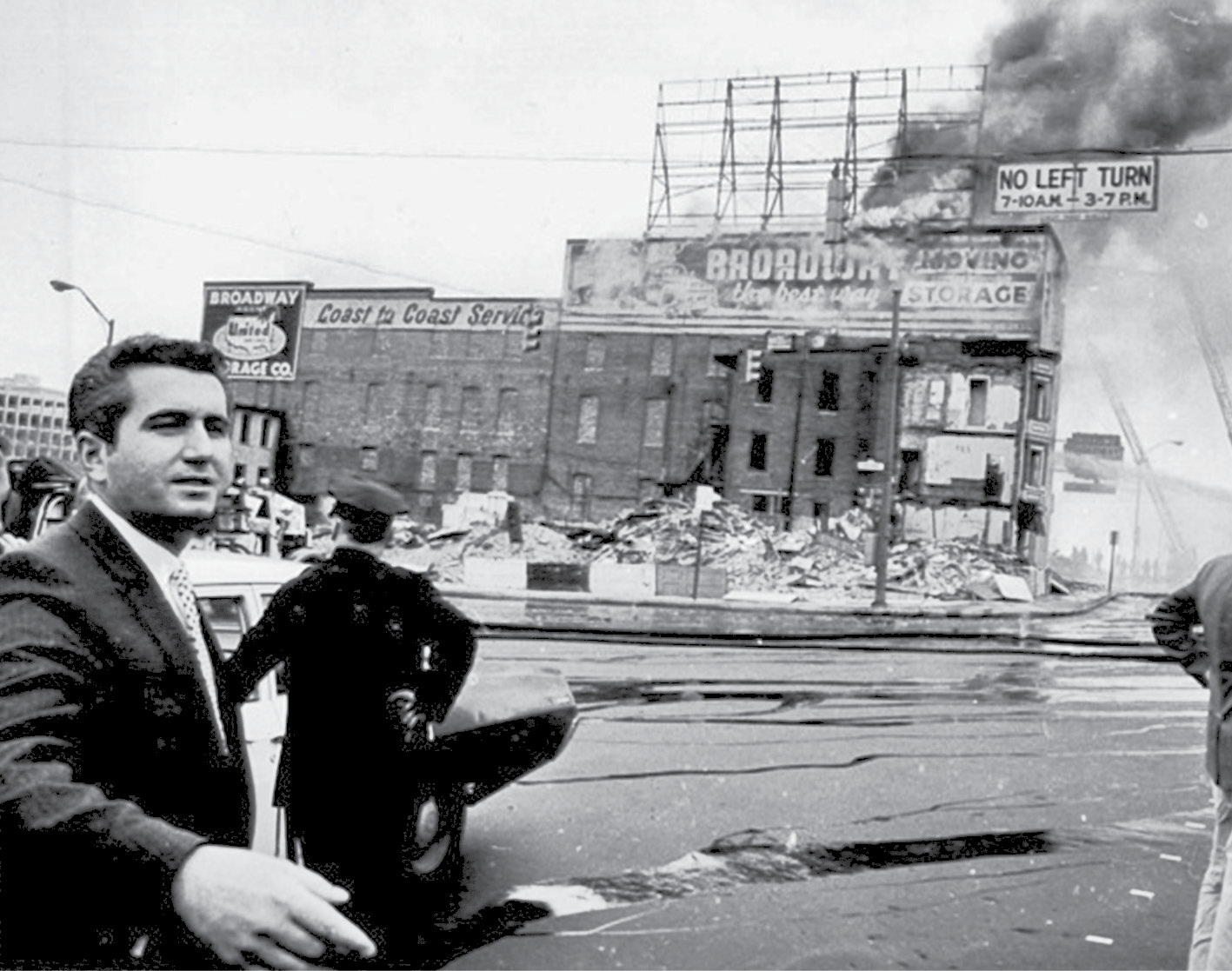

One can only guess whether Baltimore might have avoided a race riot had Martin Luther King, Jr., not been assassinated in Memphis on April 4, 1968. After two days of shock and mourning came four days of looting and arson. On April 4 and 5, the only portents of disorder were a few isolated firebombings. The first major outbreak of collective disorder occurred in East Baltimore on Saturday, April 6, just after 5:00 p.m. A mob had assembled on Gay Street. Someone threw a firebomb into a vacant house. The crowd grew as it moved up the street. Two furniture stores on North Gay Street were set afire. The uprising spread west to Harford Road, where there was extensive looting. The next day, according to Emily Lieb, “along a spine formed in part by the old expressway corridors, the disturbances made their way to West Baltimore via the Franklin-Mulberry corridor.” By 4:00 a.m. on April 7, less than 24 hours after the mob formed on Gay Street, official reports counted 300 fires, 404 arrests, and five deaths.32

The Harlem, Watts, Detroit, and Newark riots had alerted state and local authorities to prepare for a possible uprising in Baltimore. They did not assume that a Baltimore race riot was inevitable. Little more than a month before the first firebombing, Mayor D’Alesandro had reassured his constituents that the city was “not programmed for war in the streets.” Instead, Baltimore was “programmed for services,” and though the services might bear fruit for African American residents only in the long run, D’Alesandro hoped “that the show of good faith and the tangible results so far will head off any trouble here.” “We have good dialogue with all segments of the community,” he added, “and Negro leaders have indicated that they are ready to move along without violence.”33

In 1966, when Donald Pomerleau became Baltimore’s police commissioner, succeeding interim commissioner George Gelston, he expanded the force’s community relations department and established a string of police service centers where officers were on duty from noon to 8:00 p.m., seven days a week, to respond to residents’ problems and complaints.34 Together with the mayor’s stations established by D’Alesandro and the various neighborhood centers of the antipoverty and Model Cities programs, these outreach efforts might intercept private complaints and grievances before they could coalesce into contentious issues and collective protests. A month before the city’s civil disorders, a Reader’s Digest article had cited Pomerleau’s police service centers in an article titled “How Baltimore Fends off Riots.”35

City and state authorities would not rely on such measures to keep the peace. Two months before the riot, Mayor D’Alesandro issued an executive order reviving the Baltimore Office of Civil Defense, once responsible for shielding Baltimoreans against atomic bombs, but downsized and sidelined when public authorities concluded that local government could not do much to protect against nuclear holocaust. The mayor had a new mission for the office. It was to lead other city agencies “in drawing up a workable plan for handling any type of crisis situation which might occur to, and within, the City of Baltimore.” The first test exercise, based on a hypothetical explosion of a hydrocyanic tank car in a railyard, took place in late March of 1968. The test was designed to prepare the city for “practically every kind of problem, such as fire, rioting, looting, critical food supplies, and medical supplies, etc.”36

When the riot erupted, the civil defense plan specified how the city was to marshal its resources to meet the disorder. School buses, for example, were first employed to transport Maryland National Guardsmen from outlying armories to the centrally located Fifth Regiment Armory. The buses were then used to bring residents displaced by the riot to an improvised shelter in a public high school, where they received food stockpiled and prepared in school cafeterias. The buses went into service again to carry arrested looters and curfew violators to detention centers, and later to courts. The arrestees and the forces of law and order were fed from school cafeterias restocked, in part, by private donations.37

Major General George M. Gelston had continued to serve as adjutant general of the Maryland National Guard while he was Baltimore’s temporary police commissioner. In November 1967, he announced that the Guard had been working with the US Army to develop “quite detailed contingency plans” in case civil disorders broke out in Baltimore. The plans included the use of teargas rather than bullets. The Guard added three new military police units and an emergency headquarters group to serve as a command center in the event of a riot.38

Weeks before the outbreak of violence in Baltimore, the state legislature approved a measure giving the governor sweeping powers to mobilize the forces of the state in the face of riots and other emergencies. Under the new law, Governor Agnew could declare a state of emergency and designate the area to which the declaration applied. He could then impose curfews, close streets to automobiles and pedestrians, ban the sale of gasoline or alcohol, prohibit public assemblies, and call up the National Guard and state police for riot duty.39 Agnew signed the law on April 5, just in time to make use of it at 8:00 p.m. on April 6, when he declared a state of emergency in Baltimore.

Two hours later, at Mayor D’Alesandro’s request, the governor imposed a curfew in the city, banned the sale of alcohol, and dispatched the National Guard to patrol the streets. Once the Guard was activated, General Gelston assumed command of Baltimore’s police officers and the Maryland state troopers already on duty in the city. The forces of order did not operate in perfect harmony with one another. Commissioner Pomerleau suggested that the National Guard troops “be more aggressive in initiating repressive control.” Guardsmen reportedly stood by while looters ransacked stores.40 But the agents of public order shared a general commitment to restraint. The National Guardsmen carried ammunition, but their weapons were not loaded. Police officers received a message from Pomerleau reminding them of “the established Firearm Policy.” They would shoot only “in defense of themselves, fellow officers, military personnel, and citizens.” Looters were not to be shot “except in self defense.”41

In spite of the mobilization of the National Guard on Saturday evening, the disorder continued to grow. A Guard unit had to request assistance in dealing with a large crowd on Gay Street. At Preston and Greenmount, another mob stoned Guardsmen and police officers. Firefighters on Guilford Avenue asked for protection from rioters. The restoration of order was complicated by unfounded reports of snipers, looting at a hospital, and bomb scares. Governor Agnew requested the assistance of federal troops at about 6:00 p.m. on Sunday. The first contingent arrived three hours later, and overall supervision of the forces fighting the riot passed from General Gelston to Lieutenant General Robert York, Fort Bragg’s commanding officer.42

Mix-ups and miscommunication seemed to increase after the arrival of federal troops. Both D’Alesandro and Gelston had issued passes to black activists allowing them to engage in peace-restoring efforts during curfew hours. Federal troops ignored the permits and arrested their carriers. As the disorders subsided, an afternoon peace rally authorized by the city police was broken up by troops wearing gasmasks.43

On April 10, the Sun announced that the “backbone” of the riot had been broken. Six people had been killed: one in an auto collision with a police car, two in fires, one shot by a bar manager, one found with a fatal gunshot wound in a burned building, and one killed by a police officer. About 600 people were injured, but according to the Sun, only 19 were so seriously hurt that they were admitted to hospitals. Thirty-five alcoholics cut off from their usual beverages were hospitalized with delirium tremens. Over 5,700 people were arrested, a majority of them curfew violators, many of them held for trial at the civic center. Estimates of property damage ranged from $8 million to more than $13 million.44

William Donald Schaefer tried to distinguish Baltimore’s riot from the ones that broke out simultaneously in approximately 100 other cities. “We had looting,” said Schaefer, “but not with the vengeance they had elsewhere. Tommy had done things for civil rights.”45 In the aftermath of the riot, the things that “Tommy” had done seemed insufficient or irrelevant. The mayor was jeered by local businessmen at a meeting where he had hoped to offer assistance in repairing riot damage. A new organization, Responsible Citizens for Law and Order, attracted a crowd of 1,200 to a meeting where speakers criticized D’Alesandro for his restrained response to the riot. The group spokesman suggested that small businesses refuse to pay their property taxes because of the city’s inability to protect them from civil disorder. “Taxpayers’ Night” at the city council turned nasty. Councilman Dominic “Mimi” DiPietro described the audience as “a hatred crowd. They hated the way the riot was handled. They want to force the Police Department to carry a big stick.”46

Mayor Thomas D’Alesandro III, in foreground, views wreckage left by the 1968 riot following the assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. Courtesy Lt. James V. Kelly and Baltimore City Police Department

Complaints about police restraint were commonplace. Councilman Thomas Ward wrote to the mayor while the rioters were still in the streets: “You don’t handle an insurrection as if it were a civil rights demonstration. By 4 o’clock yesterday this city was . . . particularly bad due to the fact that word got around in the streets that you could get away with it . . . I suggest in the future that you handle looters (who were certainly not children) the only way looters understand—with force.” Ward complained that his neighborhood was completely without protection during the riot. The residents, he reported, provided for their own defense.47 One of his neighbors recalled that the councilman spent much of his time during the disorders on the roof of his building, armed with a shotgun.

Governor Agnew’s response to the riot received more attention than most. He called more than 125 African American leaders to a meeting at his Baltimore office. No militant leaders or advocates of Black Power were invited. Many of those attending had spent much of the previous five days on the streets, trying to get rioters to go home. Instead of thanking them for their efforts, the governor accused them of capitulating to the black militants who, he maintained, had engineered the city’s riot. Most of his audience walked out before he completed his remarks, and many of those who remained were waiting only for the opportunity to denounce him and his explanation of the riots.48

Mayor D’Alesandro wasted no time in taking exception to the governor’s remarks, which he described as “somewhat inflammatory.” “This is a bad time to say what he said”; it was a time when “we should be emphasizing reconciliation and harmony, not divisiveness.” Some Baltimoreans appreciated D’Alesandro’s position. One resident of an all-white neighborhood expressed “heartfelt support for your policy of restraint in controlling riots, and your courageous refusal to bow to demands for the kind of ‘control’ that would only make the situation worse.” State senator Verda Welcome was grateful for his “positive communication and action . . . you spoke out for peace and reconciliation. To me, your actions were phenomenal, because how can one be sure that he is right under such trying circumstances? To most Baltimoreans you have been right and we love you for it.”49

Within 24 hours of his scolding of Baltimore’s black leaders, Agnew received 1,117 telegrams supporting his “honest” and “courageous” stand. Many urged him to run for president. Only 69 took issue with his remarks.50 For white Baltimoreans, as Kenneth Durr observes, the riot “discredited a Democratic political leader and made a Republican a hero.” In ethnic, blue-collar Southeast Baltimore, some white residents had armed themselves to defend their neighborhoods during the riot. Civil authorities who granted leeway to looters, they reasoned, could no longer be trusted to protect law-abiding citizens. The governor had brought a new clarity to their social situation and legitimacy to their politics. His denunciation of Black Power activists as the architects of civil disorder targeted a new, black racism for white working-class Baltimoreans who had often been cast as racists themselves.51

ON THE ROAD AGAIN

The Sun had once referred to D’Alesandro the younger as the “Super-Charged Mayor,” “undaunted by the magnitude of the city’s problems and convinced that Baltimore is of a size to be manageable.” But manageable cities do not have riots, and there was more chaos to come. In the aftermath of the uprising, the city’s antipoverty agency unraveled when its three top administrators resigned. The agency’s remaining staff members complained that city government had “betrayed” them. They resented, in particular, that the council viewed them “as a watchdog agency to prevent riots.” The council rejected the mayor’s nomination of a former CORE activist to lead the agency—an act that D’Alesandro regarded as “a personal affront.” Almost half of the Community Action Commission resigned. A long-running dispute between the director and board of the local Model Cities agency delayed the launching of programs and services. And D’Alesandro had to address garbage, transit, and symphony orchestra strikes.52 After the riot, Mayor D’Alesandro was frequently absent from the city. Council president Schaefer served as acting mayor.

The East-West Expressway was still suspended somewhere between conception and construction. The controversy about it expanded and intensified as though echoing the anger of the riot. In August 1968, more than 30 organizations met to form a citywide coalition to fight the freeway. Representatives of both RAM and Rosemont attended. Social workers employed by the Catholic archdiocese had organized the gathering, which convened at the Catholic Center next to Baltimore’s Basilica. A representative from a coalition of neighborhood improvement associations announced that they were “unalterably opposed to the expressway and are not willing to accept a compromise.” They were prepared, he said, “to lie down in front of the bulldozers” if necessary. According to Parren Mitchell, now a candidate for Congress, “Everybody in the path of this monstrosity ought to be angry because that’s the only way you’re going to get something done.” The group chose a steering committee and elected its temporary chair. He was Stuart Wechsler, CORE’s Maryland field secretary, former associate director of CORE’s Target City Project in Baltimore two years earlier, and one of those arrested for curfew violation during the riot.53 The coalition that he headed became MAD—the Movement Against Destruction.

Plans for the East-West Expressway had continued to shift in the ongoing debate between the UDCT and the highway engineers. The engineers had operated on the assumption that most of the east-west flow would be local traffic headed for the city center. The design team’s surveys indicated that 47 percent of the volume would be through-traffic, with no need for access to downtown. The Interstate Policy Advisory Committee, chaired by Mayor D’Alesandro, gave the team $48,000 and about five weeks to come up with detailed plans for alternatives to the expressway route proposed by the engineering consultants. The team produced two options. One plan (3C) provided for two East-West Expressways. One route was designed to provide drivers with access to the central business district. It ran through the Franklin-Mulberry corridor, turned south before reaching downtown, turned east to Federal Hill, bridged the Inner Harbor, and then proceeded east through Fell’s Point and Canton to join I-95 east of the city. It resembled the original design by the Expressway Consultants, except that the bridge over the Inner Harbor would shrink from 14 lanes to 6. The reduction in size would be made possible by a second leg intended for through-traffic: this entered the city from the southwest and crossed the harbor well south of downtown at Locust Point, not far from Fort McHenry, then passed through Canton and also met I-95 east of the city. By rerouting through-traffic south of the city, the planners could reduce the number of lanes required in the Franklin-Mulberry corridor, saving about 500 homes in Rosemont and another 900 along the rest of its route.54 This was the plan favored by Jerome Wolff, Bernard Werner, and the highway engineers.

The alternative option (3A) gave drivers access to the western side of the central business district by means of a boulevard rather than a limited-access expressway. On the east was the Jones Falls Expressway, already under construction. Like 3C, this plan included an outer-harbor crossing at Locust Point to handle through-traffic, and it also provided for a Southeast Expressway that started at the southern end of I-83 and extended east through Fell’s Point and Canton, but there would be no bridge above the Inner Harbor. This was the option supported by the UDCT and the chairman of the Baltimore City Planning Commission.55

Two days before the scheduled release of the design team’s recommendations, Nathaniel Owings presented them prematurely to an audience of 500 at a banquet of the Citizens Planning and Housing Association. Mayor D’Alesandro and several council members were in the audience. Owings likened Baltimore’s decades-long entanglement in expressway planning to the nation’s long, muddled venture in Vietnam. “Everyone sensed that it was wrong,” he said, “but no one knew what to do about it.” His design team had devised an alternative that minimized disruption in the city’s neighborhoods and its central core. The Expressway Consultants’ plan, he argued, would “be wholly disruptive upon the inner city . . . The forcing of twelve or more traffic lanes with massive interchange structures through this area . . . would be physically destructive and operationally disastrous.” He recommended the 3A option—“one that does not cross the Inner Harbor.”56

Owings paid for his attempt to upstage the highway engineers. Less than two weeks after his speech to the CPHA, the director of Baltimore’s Interstate Division, Joseph Axelrod, eliminated the UDCT’s community relations staff. “The professionals,” he said, “have gotten emotionally involved with the people.” He noted that some of the people had questioned the design team about the need for any expressway at all. “We’re not looking for feedback where [residents] don’t want an expressway,” he said,“ because they’re going to get an expressway.” He presented Owings with an ultimatum: support the 3C option endorsed by the highway engineers or be fired. Owings capitulated. The Interstate Division’s payments to his architectural firm were already $700,000 in arrears. They were frozen several months earlier when Owings hired some consultants not approved by Axelrod. In closed-door meetings, the policy advisory board settled on the 3C plan endorsed by Wolff, Werner, and Axelrod.57

Owings’s open insurgency, though brief, had lasting influence. In public, at least, Owings and his team disowned their favored expressway alignment, but the 3A option won the support of city council president Schaefer and planning commission chair David Barton. Robert Embry, commissioner of the Baltimore Department of Housing and Community Development, endorsed the plan because it minimized destruction of the city’s housing stock, and a sizeable number of citizens voiced their backing of the plan in preference to the one embraced by the highway engineers.58

By the time the policy advisory board announced its recommendation in favor of the 3C route, an array of public officials and citizen organizations had already mobilized against the decision. Mayor D’Alesandro came down on the side of the critics. “If all of you are in favor of 3C,” he told the members of the policy advisory board, “it’s got to be wrong. I am adopting 3A, and I don’t want to hear any more about difficulties. I want to hear how it will be done.” The mayor’s decision included the UDCT’s boulevard access to the west side of downtown. The boulevard would be named after Martin Luther King.59

The changes came too late for Rosemont. The neighborhood had already been devastated. RAM had undermined its own opposition to the road. On the one hand, it tried to stop the expressway; on the other, it lobbied to increase compensation for residents whose homes stood in its path. State legislation approved in July 1968 granted homeowners replacement value for their houses rather than market value and provided up to $5,000 to cover residents’ relocation expenses. The Federal Highway Act of 1968 supplied much of the money to cover the new costs. Residents of Rosemont and Harlem Park who had once stood firm against the highway took advantage of the legislation to clear out.60

Robert Embry’s Department of Housing and Community Development bought condemned houses from the Interstate Division, spent an average of $16,000 to rehabilitate them, and resold 366 of them to Baltimoreans for the cost of renovation; 59 others were rented as public housing.61 Rosemont has a monument to memorialize its encounter with the road gang—a disconnected stretch of highway that never made its intended rendezvous with I-170 on the far side of Leakin Park. Baltimoreans call it the “Road to Nowhere” or “Interstate Zero.”

Mayor D’Alesandro earned some praise for his “courage” in overriding the roadbuilders to spare Rosemont and kill the Inner Harbor bridge, but the mayor soon confronted intense public anger on the east side of town, and the UDCT—once the covert ally of citizen organizations—became a target of popular attack. MAD charged that the new 3A alignment was simply “a palliative to placate those who opposed this present expressway.” The opponents included not just residents who would be uprooted by the road but preservationists determined to defend the neighborhood where William Fell had opened his shipyard almost 250 years earlier. A tourist from Long Grove, Illinois, wrote to the mayor that “Fells Point with its background of clipper ships, its waterfront residential area, its stable community would be a unique source of tourist income . . . you just don’t know what a wonderful city you have.”62

Sun reporter James Dilts, who chronicled the twists and turns of the roadbuilders, helped to ensure that the protestors would be heard far beyond the public hearings in their neighborhoods. One of the most prominent voices belonged to Barbara Mikulski. She grew up in Southeast Baltimore, where her parents owned a bakery, and became a social worker for the Catholic archdiocese. Apart from speaking up at expressway hearings, she and Alex Ticknor, pastor of a Methodist church in Canton, along with other local activists, began to plan the organization of a coalition that extended across the neighborhoods of Southeast Baltimore, a group whose agenda would extend from the expressway to other issues that faced the aging communities. In the process of creating the Southeast Community Organization (SECO), they and their allies transformed the politics of the area. Since the days of Freeman Rasin and Sonny Mahon, Southeast Baltimore had been the reliable anchor of the city’s Democratic organization. It provided an electoral base for Mayor D’Alesandro. But the highway controversy had turned the residents against their bosslets.63

At one expressway meeting in 1969, a red-faced city councilman thundered, “Let’s get something straight. Not you or the Pope or nobody else is going to stop the road from going through these neighborhoods. It’s passed. It’s done.” The audience’s booing and shouting could be heard two blocks away.64 And it was hardly done. The expressway controversy generated a new kind of neighborhood activism. One resident recalled that the “first anti-road meeting I attended . . . took place in Canton . . . and it really turned into a raucous upheaval, and I had never been to a meeting like that in East Baltimore—anti-politician, anti-establishment, anti-everything—over the road. But it was not just the road. Everything was blasted out at those [city councilmen] . . . And you really resented those politicians.” East Baltimoreans were ready for new politicians. In 1971, Barbara Mikulski ran for city council. She stood outside her family’s bakery after Sunday mass, handing out campaign literature. One voter told her that if she was half as good as Mikulski’s doughnuts, she ought to be okay. She was. Mikulski defeated the organization and seven other Polish-American candidates to win the Democratic primary for the city council and then the general election.65

Little more than a year after taking office, Mayor D’Alesandro was said to be telling friends and financial backers that he did not want to run for another term. In public, he dismissed such talk as “premature” and claimed that he had not given much thought to reelection.66 But he did hint that he might seek higher office. This suggestion damaged his relationship with Governor Marvin Mandel. The mayor complained of being “ostracized” from deliberations of the Democratic Party and charged that the governor had not consulted him concerning the appointment of a new state party chairman. A poll commissioned by the mayor showed him trailing Mandel. D’Alesandro took himself out of contention and endorsed the governor’s reelection.67

In April 1971, the mayor finally announced the decision that political observers had expected for more than two years: he would not run for reelection. He refused to give reasons for his decision. “Because these reasons are personal and concern only my family and me, I do not intend to elaborate on them now or in the future.”68 In addition to the expressway wars, D’Alesandro had confronted racial protest and conflict from the time he took office. Even more than Mayor McKeldin, he had tried to meet what he plainly regarded as legitimate black complaints against racial discrimination. In the face of an overwhelmingly white city council, D’Alesandro was a consistent advocate of the antipoverty and Model Cities programs. And he won some credit for what one black journalist called “an honest effort to bring Baltimore into the 20th Century.” In his first three months on the job, the mayor had appointed the first African Americans to serve on the zoning and fire boards, as well as the first black city solicitor, and he increased African American representation on the park board and the civic center commission. On the heels of these gains came the race riot of 1968. D’Alesandro, wrote Sun reporter C. Fraser Smith, “took the upheaval personally . . . He fell into despair.”69