PUBLIC DEBT AND INTERNAL IMPROVEMENTS

EDWARD JOHNSON, who had preceded George Stiles as mayor of Baltimore, also succeeded him. Johnson was a physician and owner of one of the city’s largest breweries, but politics was his principal occupation. The office to which he returned in 1819 was more powerful than the one he had left in 1816. While Johnson was sidelined, the Maryland General Assembly had changed the city charter to give the mayor, rather than the second branch of the city council, the authority to nominate city officials. The mayor also gained the authority to dismiss them. The measure was one of those passed during the session that began with the representation controversy, and, like other changes approved at the same session, it seemed a positive gain for Baltimore. The council members who monitored the legislative session commented favorably on the change in the appointment process, even though it augmented mayoral authority.1

Mayor Johnson was allied with Samuel Smith. Smith had come close to financial ruin as a result of the 1819 Panic, but he still had a political following. A rival faction led by John Montgomery, former congressman and Maryland attorney general, contested Smith’s control of the city, and Montgomery won the mayor’s office in 1820. For six years, Montgomery and Johnson took turns as mayor. They were evenly matched. Niles’ Weekly Register declared the municipal election of 1822 “one of the most severe electioneering contests that we have known.” Johnson won by only 48 votes out of more than 7,000.2

The Smith-Johnson faction drew much of its support from maritime Baltimore—Fell’s Point, the wards east of the Jones Falls, and those nearest to the Basin. Montgomery’s strength came from the westward and inland parts of the city, where prosperity depended on overland trade from the country’s interior and, later, on the profits of textile mills. Mayoral elections became more complex in 1824, when homebuilder and carpenter Jacob Small ran against both Johnson and Montgomery. Though Montgomery won, the defeated forces formed an alliance that solidified behind Small in the election of 1826 and gave him an overwhelming victory.3

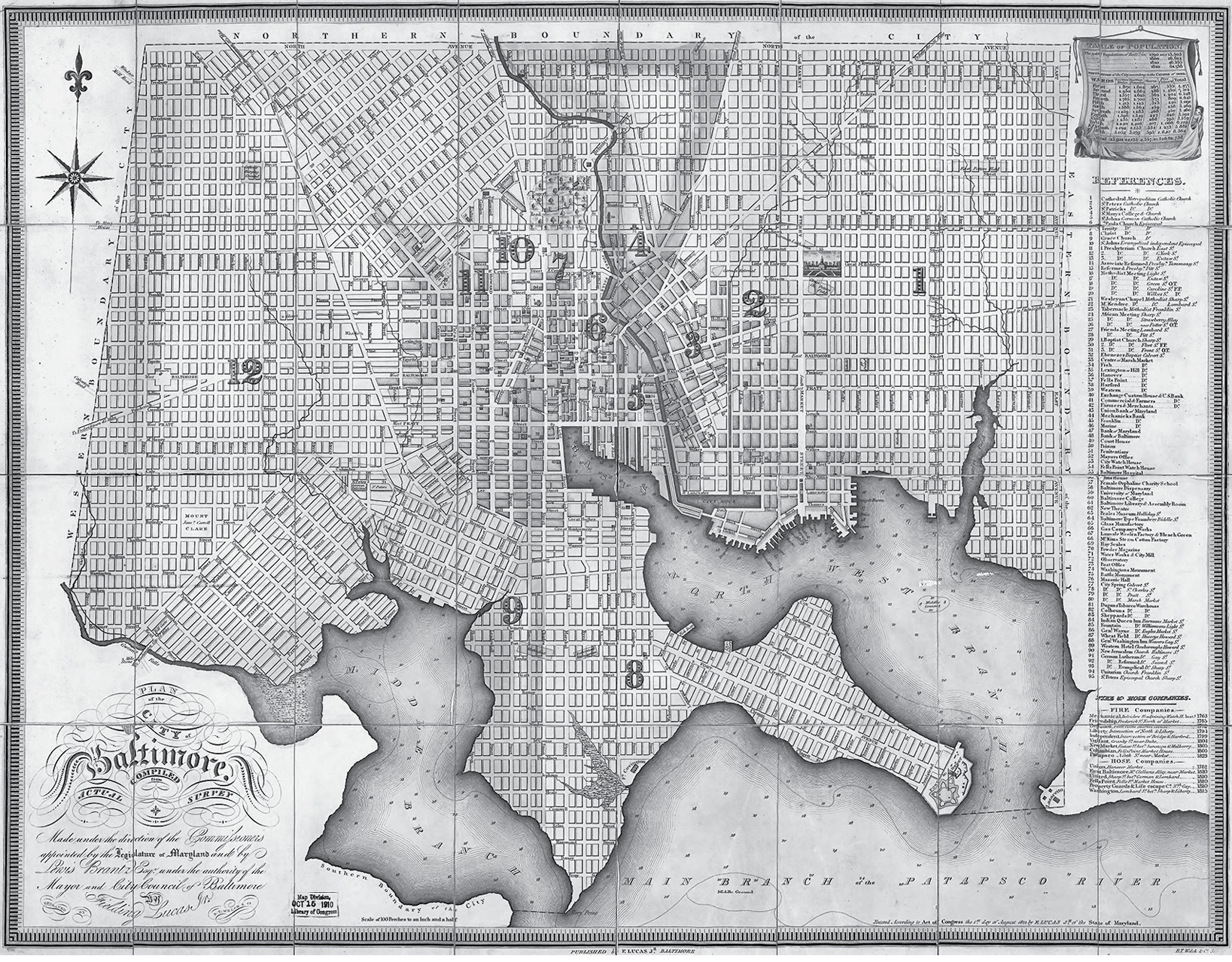

Baltimore in 1822, showing the location of wards

Small was the first mayor of Baltimore who might have qualified as a tradesman or “mechanic.” His elevation was followed by the emergence of Jacksonian Democrats as a force in both local and national politics. Small and his political patron, Samuel Smith, recast themselves as champions of Baltimore’s “workingmen” and linked local issues to the Jacksonian creed unfolding in national politics.

PUBLIC ENTERPRISE

Baltimore was building a public vision of itself, the political counterpart of Poppleton’s map. This emerged, in part, as a defensive response to external threats. Baltimore’s location—west of New York, Philadelphia, and Boston—gave the city a locational advantage that grew in value as the population drifted farther away from the Atlantic. The completion of the National Road in 1818 provided Baltimore with a connection to the Ohio River. Canals, however, threatened to cancel out Baltimore’s privileged geographic position. Geography was still decisive, but now the crucial distances were vertical rather than horizontal. Baltimore might be nearer than New York to the “waters of the West,” but the elevation it had to overcome to reach them was almost five times that achieved by the locks on the Erie Canal. The Chesapeake and Ohio Canal brought the challenge even closer to home. In effect, the C&O enabled the merchants of Georgetown to bypass the Great Falls of the Potomac and send their goods along a navigable waterway that used the Potomac Valley as a path through the Alleghenies and far to the west. The C&O would exceed Baltimore’s inland reach on the south as the Erie Canal did to the north.4

For a time, Baltimore’s political and commercial elites became preoccupied with canals of their own design. One of the most ambitious proposals came in 1820 from Robert Mills, architect of the city’s Washington Monument. In his “Treatise on Inland Navigation,” Mills proposed a canal that would link the Potomac with the Susquehanna and then give Baltimore access to both by means of a branch canal. The state legislature advanced another possibility. To soften Baltimore’s opposition to the C&O Canal, it proposed a “cross-cut” branch of the C&O—called the Maryland Canal—that would extend from Georgetown to Baltimore. A further possibility, discussed at public meetings in 1823 and 1824, envisioned a “stillwater” canal that would run northeast along the edge of the Chesapeake as far as Havre de Grace, cutting across the necks of land that extended into the Bay, to the mouth of the Susquehanna, from which it could reach Port Deposit several miles upriver. It would allow the shallow-draft boats that rode down the Susquehanna a protected channel all the way to Baltimore.5

The extravagant canal system proposed by Robert Mills was prohibitively expensive—and unworkable. But distinct political factions lined up behind the two remaining alternatives. Sometime-mayor Edward Johnson, backed by Senator Samuel Smith, led the proponents of the Susquehanna Canal, which would enter Baltimore from the east. Its backers were concentrated in the eastern wards, where Johnson and Smith generally ran strong. John Montgomery’s faction supported the “cross-cut” canal from the C&O to Baltimore. It would enter the city from the west, and its advocates were concentrated in the western and northwestern wards, where the project was likely to stimulate development and the voters tended to support Montgomery. A third faction, backing future mayor Jacob Small, consisted of property-owning tradesmen worried about the taxes needed to finance expensive canal projects.6

Though weak on results, canal politics helped to transform Baltimore. During the era of mercantile prosperity before 1815, Baltimoreans had engaged in trade singly or in small partnerships, though larger groups of investors sometimes shared the risks of chancy ventures such as privateering. But the internal improvements needed to maintain Baltimore’s economy in the era of canal building were large-scale, collective enterprises—as much political as economic ventures—and government was an essential participant.

The theorist of this new political economy was Baltimore lawyer Daniel Raymond. His Thoughts on Political Economy, published in 1820, is regarded as the first major treatise on economic theory printed in the United States.7 Raymond wanted to explain what contributed to the wealth of nations, and his views on the subject differed sharply from Adam Smith’s. Smith, according to Raymond, failed to distinguish national wealth from individual wealth. Individual wealth, Raymond argued, was the “possession of property, for the use of which, the owner can obtain a quantity of the necessaries and comforts of life.” Private wealth, in other words, was the capacity to support oneself without labor. “Talents and skills” might be a means to acquire individual wealth, but they did not constitute wealth, because the people blessed with such endowments had to exercise them to support themselves. They had to labor, and a “man who is obliged to labor for the necessities and comforts of life cannot be called wealthy.”8 The wealthy performed no labor beyond collecting rents or clipping coupons.

National wealth was different. It was not simply the aggregation of a country’s individual wealth. Labor was essential to national wealth. National wealth was “a capacity or ability to acquire, by labour, the necessities and comforts of life.” The wealth-producing capacity of industrious citizens could be enhanced by “improvements in the arts and sciences, and in agriculture, if [a nation’s] lands are in a higher state of cultivation, if its roads, bridges, canals, mills, buildings, and improvements are in a greater state of perfection than those of another nation.” Economic equality also contributed to national wealth because it enabled all citizens to participate in their nation’s prosperity and gave them an incentive to contribute to economic growth. Slavery was inimical to the wealth of nations because it excluded slaves from the enjoyment of the nation’s good fortune and also encouraged sloth among slave owners.9

Raymond offered an alternative to economic individualism. He envisioned a market in which wealth resulted from collective action to produce collective goods. The idea was essential to his argument for collectively generated internal improvements that magnified the productive power of industrious citizens. The work of building these improvements was “effective” labor as opposed to the “productive” labor of the nation’s workers. Effective labor, he argued, made productive labor more productive. Raymond was also a proto-Keynesian who, unlike many of his contemporaries, recognized that an excess of production over consumption represented not an accumulation of profit or wealth but an economic problem. In fact, Raymond argued, it was just such an underconsumption crisis that explained the extended economic slump experienced by his city and nation: the “distress” arose “from the circumstance, that consumption has not equalled production.”10

BOOMTOWN GONE BUST

Raymond extended his analysis from the nation as a whole to regions and states,11 and he might as well have been writing about his own city, Baltimore. The local economy lay in a prolonged state of stagnation. Municipal debt grew as revenues lagged. In 1819, before the full force of the national panic had hit, Mayor Johnson reported to the city council that “it evidently appears that there are ample funds if they can be collected, to pay the just demands against the City.”12 His emphasized caveat about collecting was serious. When Johnson’s rival John Montgomery was mayor, the city’s collector died before completing the tax collections for 1820; there were also significant tax arrearages remaining from 1819 and 1818. Montgomery asked the city council to authorize him to borrow $15,000 to meet immediate expenses and suggested the wisdom of having more than one collector, not just because the city might need a spare, but because the city’s taxes were “too heavy to be collected in the same year they are levied.” An additional collector might help to reduce arrearages.13 His suggestion was apparently ignored.

Baltimore was sliding more deeply into debt. In 1818, a year before the panic, the council’s Committee on Ways and Means issued a report on municipal finances. It pegged the city’s debt at a little over $212,000—about $4 million in today’s dollars—far less than today’s municipal debt. But in 1818, the amount was larger than the entire city budget. Over a third of this amount was “military debt,” money that Baltimore hoped to wring from the federal government to cover city expenditures for defense in the War of 1812. The effort to extract these funds from Washington would go on for decades. The remainder of the debt consisted of short-term notes issued in anticipation of revenue and city “stocks” carrying 5 or 6 percent interest. (Today they would be called municipal bonds.) The committee estimated that expenditures for 1818 would exceed $180,000, but revenues would fall short of this amount by $50,000, increasing the city’s debt by almost one-fourth. The committee expressed no alarm about this, but promised another report on a municipal “sinking fund” to retire the city’s debt.14

The council voted to contribute $6,000 a year to this fund. The cashiers of three local banks would serve as the fund’s unpaid commissioners. They would use the fund to purchase city stocks from the citizens or banks that held them, but only if they were offered for sale at par value or below. (There was no point in buying back municipal debt at a price higher than the amount owed.) The commissioners would add the purchased stocks to the sinking fund, and the city would continue to make interest payments on these certificates in the hope that the fund would grow large enough to erase the city’s debt. Money extracted from the federal government to pay the city’s “military debt” would also go to the sinking fund.15

In practice, the fund may have encouraged the city to go even deeper into debt. According to the Committee on Ways and Means, one of the sinking fund’s virtues was that it would “have a powerful tendency to keep up the price & credit of the Stock, which is all important for enabling the City to borrow.”16 If the price of the stock remained high, of course, the commissioners of the sinking fund would rarely be able to purchase shares below par and reduce outstanding debt, but the reliable marketability of the stock would facilitate borrowing and the growth of city obligations.

The sinking fund was aptly named. Less than a year after its creation, municipal debt approached $400,000, an increase largely due to the cost of various “improvements”: new bridges, new streets, land purchased for a new market house, expansion of an existing market, and a new powder magazine.17 The sinking fund itself added to Baltimore’s fiscal distress. The annual $6,000 payment and the interest charges on city stock held by the fund enlarged the municipal deficit. In 1819, just a year after creation of the fund, an ordinance passed by the first branch of the council called for suspension of all payments to the sinking fund and their diversion into the city treasury, where they could be used “to meet appropriations in the same manner as any other city or public money.” The second branch defeated the measure, but by 1821, Mayor Montgomery and a committee of the council again proposed to dissolve the sinking fund and use the proceeds for “extinguishment” of Baltimore’s growing debt, which had risen to more than $450,000. The proposal became a fixture of local fiscal politics, introduced almost annually.18

The General Assembly, where Baltimore had recently won additional autonomy in taxing and borrowing, now posed another threat to the town’s fiscal stability. In 1822, John Pendleton Kennedy, one of the city’s two representatives in the house of delegates, sent an ominous report suggesting that the legislative session would be “marked by more than one act of unequivocal hostility to our city.” Kennedy, a young lawyer with literary as well as political ambitions, thought that the assembly was “characterized in a greater degree by a disposition to subject us to the convenience of the counties than I have ever known it before.” His particular concern was the rumored preparation of a bill that would transfer Baltimore’s auction tax and its receipts to the state treasury. The loss would be significant. In 1820, the auction tax accounted for almost 11 percent of municipal revenue, but before the Panic of 1819, it had yielded 30 to 40 percent.19 The city council was sufficiently alarmed to authorize the mayor to “select such gentlemen of the City” as he thought appropriate to travel to Annapolis in an effort to secure the auction tax against legislative pilfering.20

In Annapolis, however, the debate veered, improbably, toward the issue of “internal improvements.” One of the earliest improvements underwritten by the federal government was the National Road, begun at Cumberland, Maryland, in 1813 and completed to Wheeling on the Ohio River in 1818. Various private turnpikes extended from Cumberland eastward to Baltimore and other seaboard cities. In 1821, a delegate from Washington County introduced a resolution that renounced the state’s claim to the city’s auction tax, provided that Baltimore would purchase the private turnpike extending from Baltimore to Boonsboro or the road from Hagerstown to Cumberland and make them toll-free roads. Both Boonsboro and Hagerstown were located in Washington County. The delegate acknowledged Baltimore’s financial “embarrassments” but argued that using funds generated by the auction tax to purchase the turnpikes would “ultimately return [those funds] into her own coffers.”21 Like those who wanted the state to expropriate the city’s auction tax, the Washington County delegate sought to exploit Baltimore’s declining but still sizeable revenues to advance his own constituency’s interests.

A delegate from the Eastern Shore complained that the resolution was calculated to prevent the assembly from voting on the auction tax at the current session, since it would take months for Baltimore to arrange the purchase of the turnpikes. Baltimore’s two delegates frankly acknowledged that this was precisely their reason for supporting the proposal. John Pendleton Kennedy noted that the resolution advanced by his colleague from Washington County might induce Baltimore to accept a compromise to keep its auction duties. Baltimore, said Kennedy, was burdened by debt and “suffering under a taxation tenfold heavier than that felt by any other portion of the state.” But Kennedy announced that he would nevertheless vote in favor of the resolution because it would postpone the legislature’s consideration of the auction bill until the following year. Baltimore, he added, was a “great patron of internal improvements” and would embrace the purchase of the toll roads, as well as other projects, if its circumstances were more prosperous.22

The resolution to create toll-free roads was overwhelmingly defeated, but the auction bill did not pass either. Baltimore’s financial circumstances, however, continued to deteriorate. In his annual message for 1822, Mayor Montgomery cited the city’s heavy debt and emphasized the need for public thrift—“no other than the ordinary expenses of the City are deemed necessary.” Surplus revenue, if any, should be “applied to the discharge of so much of the city debt or a reduction of the rate of taxes may be made as the Council may consider expedient.” But little more than a month after delivering this lecture, Montgomery returned to the council for approval to borrow $15,000 in anticipation of city revenue. The second branch refused him. Ten days later, however, both branches approved his request to borrow up to $20,000.23

The city’s growing debt may have had some role in Mayor Montgomery’s defeat in the hard-fought mayoral campaign of 1822. One of ex-mayor Johnson’s partisans claimed (inaccurately) that the city owed only $15,000 when Johnson left office in 1820 but was burdened with over $400,000 in debt at the end of Montgomery’s term. So many other claims, charges, insults, and countercharges were fired off during the campaign that it is impossible to determine how much weight the issue of municipal indebtedness carried in the election’s outcome. Montgomery was also attacked for neglecting to pay his dues in the Hibernian Society (the Irish defaulter was actually another John Montgomery). Johnson was accused of being “indolent.” His friends referred to his exertions—as both mayor and physician—in the “fever of 1819.” Montgomery was described as “an aristocratical man . . . who rather thinks of gratifying personal feuds and partialities than public benefit.” Another citizen claimed that Montgomery was “the poor man’s friend.” Johnson’s supporters countered that their candidate was not only the poor man’s friend but “the widow’s hope” and “the orphan’s benefactor.”24

In his first annual message after being returned to office in 1822, Mayor Johnson chose to compare the city’s current financial condition not with the previous year’s but with its status on November 1, 1820—weeks after he had lost the office to John Montgomery. His figures showed that city debt had increased by over 40 percent while his opponent was mayor. Municipal debt may not have been the election’s decisive issue, but Johnson clearly made it an issue after he took office.25

Johnson’s strictures against municipal expenditure were even more severe than Montgomery’s. According to Johnson, “the particular condition of the city will not admit of any expenditures . . . that the immediate welfare of its inhabitants does not imperiously demand.” The mayor cautioned the members of the council to “give their most serious consideration whether we are in a situation to attempt anything new.” He was willing to make only two exceptions to his injunctions against new spending: when money was needed to preserve “the Health of the City” or “our navigation and harbor.” Outside those priorities, he hoped that he and the council would be “united in a fixed and determined resolution not to increase the amount of our debt.” Only weeks later, the council granted the presidents of its two branches and the mayor the joint authority to issue up to $80,000 in city stock at 6 percent interest, money apparently needed to meet the city’s operating expenses.26

THE CANAL CRAZE

There was another odd departure from Mayor Johnson’s regime of austerity. In spite of his reluctance “to attempt anything new,” he left undisturbed a $50,000 appropriation for improving navigation on the lower Susquehanna River, where swift currents and navigational obstacles interfered with upstream shipping. Heavy-timbered, shallow-draft “arks” and rafts made the one-way trip downriver and were broken up for lumber when they completed the journey. As early as 1801, work had begun on a nine-mile canal parallel to the river so that boats could move upstream past the worst of the rapids. Its engineer was Benjamin Latrobe, architect of the US Capitol and founder of an illustrious line of Baltimoreans. The first Susquehanna Canal was not successful. It was too small to accommodate the larger craft descending the Susquehanna, and it had been excavated with a curved bed not suited to accommodate flat-bottomed canal boats. But Baltimoreans had not abandoned the canal that might tap the trade of the Susquehanna Valley, drawing it away from Philadelphia. If successful, the project might remedy the “Stagnation of our Commerce,” which Mayor Johnson blamed for the decline of municipal revenue.27

The Susquehanna venture also seemed to provide the city with its only hope of responding to the threat of a “Potomac” canal that might negate Baltimore’s locational advantage for trade with the West. The Potomac proposal was all the more aggravating because, if the General Assembly embraced it, Baltimore might have to bear a substantial share of the project’s cost. Mayor Johnson wrote to the city council, noting that an act to reincorporate the Potomac Canal Company was being considered in Annapolis, and he urged “the adoption on your part of the most prompt & efficient measures to defeat this project.”28

Four members of the city council dutifully traveled to Annapolis to defend the interests of Baltimore. They found that the latest version of the Potomac Canal bill provided for an enterprise supported entirely by private funds. Baltimore, in other words, would not be compelled to contribute. Consideration of the bill had also been delayed until the next session of the assembly (when it was defeated). But the extended discussion of the Potomac Canal and the difficulties that it faced seems to have put Baltimore’s four councilmen in a canal-building frame of mind. They returned to Baltimore with a report that covered not only the fate of the Potomac Canal Company but an ambitious proposal for a canal that would carry freight from Baltimore to “our mighty river Susquehanna” at a point above the rapids that interfered with navigation. A canal “from this beautiful river to Baltimore, taken out above all the obstructions on the river would be from 60 to 70 miles (one third the length of the Potomac Canal) without crossing or perforating a single mountain.” The General Assembly “at the instance of our delegates” had already appointed commissioners to consider the feasibility of such a canal, as well as another proposed canal that would link Baltimore with one to be built in the Potomac Valley.29

The councilmen had been sent to Annapolis to kill one costly canal but returned with proposals for two others. They gave only passing attention to the reduced state of their city’s treasury and commerce, but confidently trusted “that in proportion to the extent of our depression and inactivity, will be the renewed vigor and awakened spirit with which the people and the government will unite in this great work.” They were not alone. Mayor Montgomery had chaired a public meeting to discuss the Susquehanna Canal project in April 1822, and soon afterward, Baltimoreans were making voluntary donations to finance an engineering survey for the enterprise. One local visionary claimed that a further Susquehanna Canal should also be dug from the headwaters of the river in Lake Otsego to Lake Erie, thus making it possible that “a man may walk in the water from Baltimore to Quebec.”30 Though this dreamer may have held odd ideas concerning the use of canals, the prospect of canal digging seems to have lifted Baltimore’s political and business classes from somber preoccupations with debt and decline to grand schemes for what J. Thomas Scharf called “a fresh start in the race of prosperity.”31

The Maryland Canal Commission appointed to examine the prospects for a Susquehanna waterway did nothing to dim Baltimoreans’ enthusiasm for their canal-to-be. The commissioners mapped what they regarded as a technically feasible route, with the assistance of officers on loan from the army’s topographical engineers. Thomas Poppleton helped to plan the “leveling” of the route, and Jehu Bouldin surveyed it. The canal would leave the Susquehanna just above the Conewago Falls in Pennsylvania and run along the west bank of the river to Havre de Grace in Maryland, a distance of more than 56 miles, at an estimated cost of about $1.8 million. If the canal ended at Havre de Grace, canal boats’ cargoes would have to be transferred to other vessels. The narrow, shallow-draft canal boats could not manage the currents, tides, and swells of the Chesapeake Bay—and the mules and horses that pulled them would have to swim. The Susquehanna “arks” had to shift their cargoes to other boats once they reached the Bay, and their experience suggested that the business of transferring freight to bay vessels might delay its arrival in Baltimore by as much as five days. The stopover could be avoided by cutting another leg of the canal southwest from Havre de Grace to enter Baltimore’s harbor, not far from Fell’s Point. The distance would be something over 36 miles and add $1.4 million to the cost. This leg of the canal would cut more than 30 miles from the journey because the boats would not have to sail down the Chesapeake to the mouth of the Patapsco and then up the river to Baltimore. This, and the ability of canal boats to make the trip without any transshipment of cargoes, might save as much as eight days on the trip from Havre de Grace to Baltimore.32

The commissioners were especially sanguine about the wealth that would flow to Baltimore by means of the Susquehanna Canal. Some of that wealth, they recognized, would come to Baltimore at the expense of Philadelphia. But the bounty of “Susquehanna country” embraced much more than the wealth of Philadelphia. The region’s population was “considered as among the most active, vigorous, and productive of any within our union,” and beneath its soil, the report claimed, were immense deposits of iron ore and coal.33

The commissioners concluded with a plea that the canal of their dreams should not be abandoned to the meanness of private enterprise. The Erie Canal, they emphasized, “progressed under the direction, and has been the work of a free people.” It was a state project. The Susquehanna venture should also move forward under public auspices. “But, if by any misdirected notions, the grand work of opening a canal from Baltimore to Conewago, should be fashioned into the shape of a joint stock company, and thrown into the market, among money dealers and speculators, to be gambled for, by having its vast merits noised and bruited abroad, until immense sums have been filched from some and squandered by others, and all without effect, we should calculate on beholding the effort terminate in an abortion and then on its dropping into oblivion.”34 The feeble accomplishments of the Potomac Canal Company, chartered in 1784,35 may have contributed to this prejudice against the use of private capital for public improvements. The privately financed corporation was formed by Maryland and Virginia to improve navigation on the Potomac as far upriver as possible and to build a canal from that point to Cumberland. But the company accomplished little, and an investigation of its status conducted in 1821 found it insolvent and incapable of completing the project assigned to it.36

Not long after publication of the Maryland Canal Commission’s report, a town meeting assembled in the rotunda under the dome of the new Exchange Building in Baltimore, designed by Benjamin Latrobe. The citizens in attendance were asked whether the city should give priority to the Susquehanna Canal or to another canal that would connect Baltimore, by way of the Potomac, with the Ohio River. Robert Goodloe Harper, a former congressman and US senator, made the case for a newly conceived Chesapeake and Ohio Canal. This had succeeded the long-stalled Potomac Company plan, and Harper argued for a lateral branch of the C&O that would reach Baltimore and carry its trade on the C&O, through Pittsburgh, to the Ohio River. He argued that the arks and rafts of the Susquehanna had already given Baltimore unrivaled control of the downriver trade; building a canal alongside the Susquehanna would bring no great gain for the city. Robert Winchester, one of the commissioners who had recommended the Susquehanna route, countered that it would give Baltimore access to “the fairest portion of the United States,” not the frontier West, but a region already populated, developed, and prosperous. By a large majority, the assembled citizens declared themselves in favor of the Susquehanna option.37

A joint stock company, the Susquehanna and Tidewater Canal Company, eventually undertook the project. The work faltered in the face of unexpectedly high costs—about $80,000 a mile, more than twice the commission’s estimate. The Maryland legislature had to be persuaded to subsidize the venture; the Pennsylvania legislature refused at first to grant a right of way to a canal that challenged the commercial prosperity of Philadelphia. Construction would not begin until 1835. The canal was completed in 1840, but without the extension from Havre de Grace to Baltimore. The canal company was insolvent by 1842.38

INSTITUTIONALIZING INDEBTEDNESS

It took only an imaginary canal to reanimate Baltimore’s commercial aspirations. In fact, the imaginary canal inspired larger hopes than the actual, disappointing canal could possibly have sustained. A more general enthusiasm about internal improvements of all kinds held out hope that municipal indebtedness and commercial stagnation might end and that Baltimore might once again become the boomtown of the eastern seaboard. These expectations were not fully realized. Internal improvements may have energized commerce, but they led Baltimore’s government to higher levels of indebtedness than it had ever risked in the days when the city’s health, harbor, and water supply were its primary concerns.39

Baltimore refashioned itself for a new era of public expenditure. In 1826, the commissioners of the sinking fund were replaced by three commissioners of finance, consisting of the mayor and the presidents of the city council’s two branches. The principal goal of the sinking fund had been to retire the city’s debt, but the primary mission of the new commissioners was to manage the debt. The commissioners of finance were to receive an annual appropriation of $27,000, along with any proceeds generated by the sale of city-owned real estate. They were to use these funds to cover the costs of debt service. Only if a surplus remained after these obligations had been met were the commissioners authorized to purchase city stock from private investors and thereby reduce outstanding public debt. Even the money for debt service might be held up by the mayor, who was instructed to release funds to the commissioners “in such payments and at such times as the Treasury shall best admit.”40

Baltimore’s “fresh start in the race for prosperity” would be sustained by deficit spending, but local canal promoters looked to the state, as well as the city, for construction funds. In 1825, a Maryland Convention on Internal Improvements assembled in Baltimore. Its purpose was to reach some consensus about the competing canal projects being promoted in different parts of the state and to identify those with the strongest claims to state support.41

The quest for consensus was messy. A delegate from Allegany County wanted a canal from Baltimore to Allegany County. A representative for Harford County promoted the Susquehanna Canal, which would pass through Harford County. They agreed that the C&O Canal would facilitate trade between America’s East Coast and the West, but this very fact “invested the proposed . . . canal with a national character” and made the venture a suitable project for “the energies and funds of the government of the United States.” The federal government should finance the C&O, in other words, and Maryland should invest in an Allegany canal—or the Susquehanna Canal. Samuel Ellicott, a Baltimore City delegate, agreed that the C&O should be a federal project, but Maryland should underwrite a connection between the C&O and Baltimore, while simultaneously engineering a grander version of his city’s favorite canal along the Susquehanna.42

A delegate from Allegany County, reaching for consensus, integrated all of these proposals along with others in a grandiose extravaganza of engineered waterways that would create a “continuous line of interior canal navigation . . . from Lake Erie to the Ohio, from the Ohio to the Potomac, from the Potomac to the Patapsco, from the Patapsco to Havre de Grace, on the Chesapeake Bay, from the Chesapeake Bay to the Delaware Bay, from the Delaware to the Hudson and thence by the Buzzard and Barnstable canal through to Boston.”43

Toward the close of the proceedings, John Pendleton Kennedy delivered an admonition against entrusting the canal projects to private enterprise. He echoed the warning of the Susquehanna Canal Commission two years earlier, but was even more harshly skeptical about corporate capitalism. In making the case for the C&O Canal, Kennedy cited the need for “a security that the canal to be constructed, shall be managed with reference to the national convenience; and for the people’s good.” “Under such a conviction,” he continued, “this convention do utterly reprobate the idea of risking so grand an enterprise upon the feeble means of an incorporated company . . . drawn together by the lure of gain.”44

For Kennedy, at least, the “market revolution” elicited profound reservations about private enterprise, and he was not alone. Daniel Raymond’s critique of economic individualism reflected a similar skepticism. But Kennedy’s warnings were omitted from the report of the Internal Improvements Commission. A private corporation, supported in part by public funds, undertook construction of the C&O Canal. The arrangement reflected the General Assembly’s longstanding preference “to run the state without the need for direct taxation” by financing its operations with “income derived from state investment in corporations chartered by the state legislature.”45 The canal company exhausted its capital far short of Pittsburgh and the Ohio River. Almost 25 years of planning and construction carried it only as far as Cumberland, where it stopped.46 The Baltimore City Council was decidedly cool toward proposals to extend the canal beyond Cumberland. The estimated cost of the extension was $2.5 million and would add to the state’s already considerable debt. But the council insisted that, if the state extended the C&O to the Ohio, it should also provide for the construction of the Maryland Canal from Washington to Baltimore.

General Simon Bernard, former aide-de-camp to Napoleon, was now an officer of the army’s board of engineers. His study of the proposed Maryland Canal pronounced it impossibly expensive, and he reached the same conclusion concerning Baltimore’s Susquehanna project. According to Scharf, “our people may be said to have sat down, like the Israelites of old by the waters of Babylon and wept.”47