four

The Temple Regained

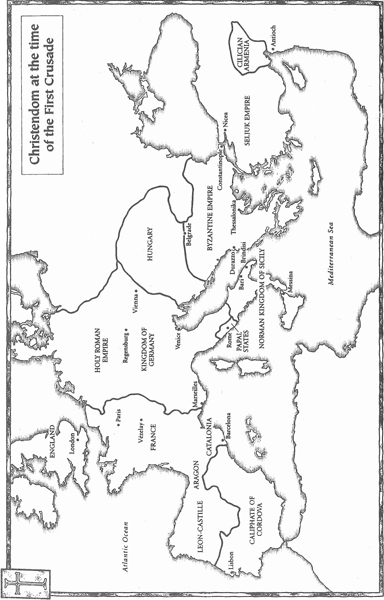

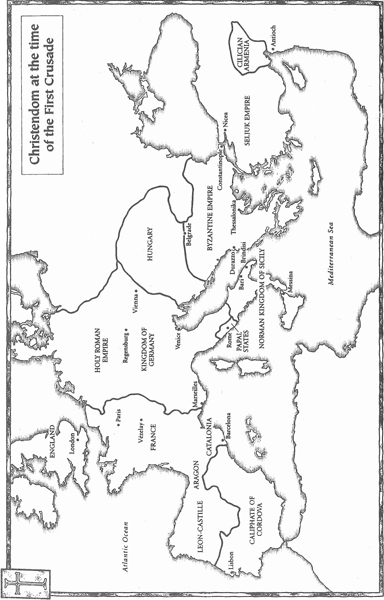

On the Iberian Peninsula, the Muslim conquest was no sooner completed than the Christian counter-attack or Reconquista began. Visigothic nobles who had retreated into the mountains of Asturias joined forces with the native inhabitants to resist the invaders, and around 722, ten years before the rout of the Muslim army at Poitiers by Charles Martel, they defeated an Islamic force at Covadonga under their leader Pelayo. They later occupied Galicia in the north-western corner of the peninsula and established a frontier along the Douro river between Christian and Muslim Spain.

In the west of Spain, the fierce tribe of Basques regained their independence and towards the end of the eighth century Charlemagne’s Franks invaded Catalonia, capturing Barcelona in 801. However, the chief additions to Western Christendom in the ninth and tenth centuries came from the defeat and conversion of pagan tribes in northern and eastern Europe – the Saxons, the Avars, the Wendts, the Slavs. Byzantine Christendom also expanded through a mix of conquest and conversion. Though there was as yet no open division between the Byzantine Orthodox and Roman Catholic churches, there was a certain competition for the allegiance of convert kings. The Kingdom of the Rus with its capital in Kiev went to the Patriarch of Constantinople together with Bulgaria and Serbia; Hungary and Poland went to the Pope.

Christianity, despite the missionary efforts of Anskar and Rembert in the ninth century, did not take root in Scandinavia until the tenth. The Vikings, whose piratical raids had all but destroyed Celtic Christianity, were late converts; among the first was Rollo who in 918, with a group of followers, had founded a colony in the valley of the lower Seine with the sanction of the King of France. Because of their provenance they were known as the men of the north – Nordemann in German: Normand in French.

* * *

The menace of Islam was ever present in the minds of the Christian leaders but their martial energies were largely dissipated in fighting one another. In Gaul, under the Merovingian kings, where quarrels among the nobility ‘resembled nothing as much as the fighting of wild beasts’,76 the state had been powerless to ensure even the most rudimentary public order. For his own security and that of his family, a man had no alternative but to buy the protection of a powerful neighbour with some form of service, usually as a warrior in his private wars. It was also the only way to protect his land which, with the collapse of commerce and a paid administration, was the sole source of livelihood. The term used for the subordinate’s commitment was vassalage, and that for his ‘pay’ was a benefice, usually a grant of land but sometimes the income of ecclesiastical institutions. The contract was sealed with solemn vows and, while using the language of servitude, became ‘a coveted status, a mark of honour, at any rate where direct vassalage to the king was concerned’.77

In theory, this feudal system was a pyramid that covered at its base the entirety of Western society. In reality, the position at the apex was disputed between popes and emperors; the link was notional between emperors and kings, and problematic between kings and their barons. The most effective bonds were formed between the great dukes, counts and princes – descendants of the vassals of the Carolingian sovereigns – whose territorial holdings were sufficiently large to sustain an effective force of vassals and therefore remain independent of the state. Their vassals in turn would command the allegiance of lesser knights whose wordly possessions might amount to no more than a horse, a lance, a sword and a shield; but whose descent from the caste of Carolingian warriors ensured membership of the social elite. In theory if not in practice, this allegiance was a matter of choice: however meagre his resources or humble his origin, the knight remained a free man under the law and had the right of trial in a public court.

Some vassals depended entirely upon their liege lord, even for their horse and armour. Others, though they received property as a benefice, might also own land in their own right or as a tenant of an ecclesiastical foundation. Although he might feel great loyalty to the lord whose ‘man’ he was, and feel honour bound to join in his vendettas, his commitment was not open-ended but was governed by custom and law: for example, his obligation to provide military service was limited to forty days. His allegiance could also shift if either party was unable to fulfil his obligation; knights took service under different princes who could provide them with horses or with pay. The bond between lord and vassal was not necessarily hereditary but tended to become so: intermarriage created a cousinage that formed the basis of loyalty to a clan.

* * *

Violence was also endemic in the eastern empire and the caliphates of Islam where each succession was usually the occasion for a civil war; but whereas a Byzantine emperor or a caliph could gather into his hands all the reins of power of a unified state, the different principalities that had come into being in the Western Empire would never, after Charlemagne, combine under a single sovereign.

This had grave consequences for the Papacy which, with the disintegration of Charlemagne’s Empire under his quarrelling successors, ‘was left defenceless in the snakepit of Italian politics’.78 The last effective Pope of this period was Nicholas I (858–67). During the hundred years which followed his death, the position of successor to Saint Peter became the disputed gift of powerful Roman families such as the Theophylacts. In 882 John VIII became the first pope to be assassinated – beaten to death by his own entourage. Stephen VI had the corpse of his predecessor but one, Pope Formosus, disinterred and enthroned in his pontifical robes so that he could be condemned for perjury and misuse of his powers. The three fingers of his right hand which he had used to bless his flock were hacked off and his body was thrown into the River Tiber. Shortly afterwards, Stephen was deposed by the supporters of Formosus, incarcerated and subsequently strangled.

The personal depravity of many of these popes did not necessarily mean that they were incompetent in their government of the Church. John X, brought to the throne of Saint Peter by the powerful Theophylact family, organised a coalition of Italian states against the Muslims who had harassed Roman territory for the past sixty years and led the force that after a three-month siege took their stronghold at the mouth of the River Garigliano. Two of the popes appointed by the Roman despot Alberic II (Leo VII and Agapitus II) were sincere and effective reformers. Even John XI, the bastard son of Marozia Theophylact, sanctioned a reform in the Church that is germane to the story of the Templars: he took under the direct protection of the Roman pontiff a community of Benedictine monks from an abbey in Burgundy called Cluny.

* * *

Cluny was established in 910 by the Duke of Aquitaine, William the Pious, to atone for the sins of his youth and ensure his salvation in the world to come. The man he chose to lead the community was Berno who came from the Burgundian nobility and was then the abbot of the remote Abbey of Baume. With Berno, the duke chose a fine site for his foundation in the hills to the west of the River Saône.

Over the previous century, Benedictine monasticism had gone into decline. The generous endowments of past generations had made the monasteries rich and therefore vulnerable to the demands of the descendants of their former benefactors. Their revenues were used to provide for the younger sons of the local nobility who, with no religious vocation, would be foisted on the religious communities as priors or abbots. Local bishops, often related to the secular lords, would also exploit these monastic offices to reward their dependants.

To ensure the free election of their abbot, the community of Cluny was placed by Duke William under the direct protection of the Pope in Rome while Berno put through reforms to arrest the decline in monastic practice and restore the rigours of Benedict of Nursia’s original Rule. The movement flourished, and a network of subsidiary houses was founded that remained under the direction of the community at Cluny. It was Berno’s successor as Abbot of Cluny, Odo, who petitioned the dissolute Pope John XI to extend papal protection to a new monastery at Deols. Odo, like Berno, came from the Frankish nobility and he established the Cluniac tradition of monks who were aristocratic but genuinely humble, shrewd but utterly devout, learned but also simple, and always humorous and cheerful.

Odo’s noble birth enabled him to confer easily with popes and princes, and they in turn looked to him. Pope Leo VII invited Odo to Rome where he negotiated a settlement between Alberic II and King Hugh of Italy and initiated reforms of the monastic communities in Rome and the Papal States, among them Benedict of Nursia’s first Abbey of Subiaco. He was succeeded by a series of able, holy and long-lived abbots – Aymard, Mayeul, Odilo, Hugh, Pons and Peter the Venerable – who together covered a span of two hundred and eleven years. Like Odo, they became the friends and counsellors of emperors, kings, dukes and popes. In 972 the revered Abbot Mayeul of Cluny was captured as he crossed the Alps by Saracen raiders from their base at Fraxentum in Provence. He was later ransomed but this scandalous act of brigandage provoked a response that finally drove the last Muslims out of France.79

The influence of Cluny in the century that followed its foundation was to be immense: of the six popes who were monks between 1073–1119, three were from Cluny; however, it was not the reforming zeal of the Cluniac Benedictines that pulled the papacy out of the mire of corruption but the intervention of German emperors. After Charlemagne’s death, the Teutonic principle of equal division among a king’s heirs had triumphed over the Roman one of the transmission of an indivisible empire. His heritage had therefore been split into three – France in the west, Germany in the east, and between them a long and narrow middle kingdom stretching from Flanders to Rome which came to be called Lotharingia – in German Lottringen, in French Lorraine – because it was given to his eldest son Lothar who also inherited the imperial crown.

The century which followed the death of Charlemagne saw ‘the nadir of order and civilisation’,80 and it was not until the German princes chose the Saxon dukes as their leaders that Pope Leo III’s concept of a new Roman imperium was revived in a modified form with sovereignty over Germany and parts of Italy vested in a German prince. This ‘Holy Roman Empire’ was essentially the brainchild of the Duke of Saxony, Otto I or Otto the Great who, having defeated the Magyars, marched across the Alps in 951 to assert his claims over Italy. Having been acknowledged as King of Italy at Pavia, he led his army to the gates of Rome. There, after pledging himself to respect the liberties of the city and protect the Holy See, he ascended the altar of the Church of Saint John Lateran with his queen, Adelheid, and was crowned emperor by the corrupt and youthful Pope, John XII.

This revival of the Roman Empire was not just a political expedient or a picturesque fiction. Western Europe had arrived at an understanding of itself as ‘a single society, in a sense in which it was not before, and has not been since’.81 Although a man’s immediate loyalty went to his feudal lord, he defined himself not as an Englishman, a Frenchman or a German but as a Christian whose faith’s universal dominion was visible in both Church and state. ‘The first lesson of Christianity was love, a love that was to join in one body those whom suspicion and prejudice and pride of race had hitherto kept apart. There was thus formed by the new religion a community of the faithful, a Holy Empire…’ that made ‘the names of Roman and Christian convertible’.82 There could be no national churches because there were as yet no nations: if the unpolitical man of the Middle Ages had been capable of conceptualising his sense of community, he would have said that he lived in a world-state.

Unfortunately, the co-operation of pope and emperor upon which this universal government depended was rarely achieved: and as the Cluniac reformers gained ground within the Church, their determination to emancipate the clergy from the interference of lay powers confronted the authority of the emperors. A complicating factor was the importance attached by the popes in Rome to their standing as secular princes. The legal basis to their claim to a large swathe of central Italy was the supposed ‘Donation of Constantine’ who in return for a miraculous cure from leprosy at the hands of Pope Silvester I had bequeathed Rome and undefined parts of Italy to the successors of Saint Peter. The document that established this donation was forged in the middle of the eighth century when the Frankish King Pepin had saved Pope Stephen II from the Lombards and confirmed the Donation of Constantine as the Donation of Pepin. Whatever the legality of the forgery, it was accepted as valid by the Franks; and it could be thought that the right of conquest made the Papal States Pepin’s to give. However, it was vehemently contested by the eastern Byzantine emperors who, as we have seen, were to reclaim large parts of Italy and rule through their exarchs from Ravenna; and it also came to be disputed by western emperors who regarded themselves as the heirs to the Caesars and, consequently, overall sovereigns of all those territories that had once formed part of the Roman Empire.

As a result of these counter-claims by the eastern and western emperors, the policy of the popes in Rome was always to maintain a balance of power in Italy which enabled them to tip the scales in their favour. But sovereignty over the Papal States was by no means the only difference between the popes and the German emperors. More acute was the power of secular princes to make ecclesiastical appointments within their domains. In theory, an abbot was chosen by his community and a bishop by his diocesan clergy but, as we saw in the case of Martin of Tours, their election was frequently contested. It was not simply a matter of a candidate’s spiritual calibre but, more significantly, his political loyalties and affiliations. Bishops throughout the former Roman Empire had often taken up the task of secular administration within their diocese. They had also, thanks to past endowments, become powerful landowners with armed vassals at their command. Particularly in Germany, dioceses like Cologne, Münster, Mainz, Würzburg and Salzburg were sovereign principalities. The loyalty of the man who brandished the crozier was therefore of critical importance to the Holy Roman Emperor and the German princes; but the right to the crozier came with the pallium, the band of white wool worn over the shoulders that was the symbol of his office and in the gift of the Pope.

The growing differences between pope and emperor came to an open rupture during the pontificate of Hildebrand, a man from a modest family in Tuscany who had been the indispensable counsellor of the four previous popes before being chosen as pope himself by popular acclaim in 1073, taking the name of Gregory as a tribute to Gregory the Great. Like his illustrious predecessor, this Gregory was a man of exceptional intelligence and ability, with long experience in the administration of the Church. He was energetic in promoting reform, issuing decrees against simony (the sale of ecclesiastical appointments) and clerical marriage, but also in forbidding the lay investiture of bishops, a measure that brought him into direct conflict with the Emperor, Henry IV. Henry convened a synod of German bishops to depose Gregory; Gregory in turn excommunicated Henry and released his subjects from their vows of allegiance; for among the claims he made for the Roman pontiff in his Dictatus papae was a supreme legislative and judicial power over all temporal as well as spiritual princes.

The Pope’s dispensation of their vows of fealty was seized upon by Henry’s opponents and obliged the Emperor, in 1077, to seek out Gregory at the castle of Canossa in northern Italy and profess repentance and seek forgiveness, standing barefoot in the snow at its gate. But Henry’s humiliation at Canossa did not end the conflict which, partly because of Gregory’s uncompromising nature, continued throughout his reign. In 1084 he lost Rome to Henry’s forces and was only rescued by a new power that had arisen to the south of the Papal States – the Norman kingdom of Sicily.

* * *

‘The establishment of the Normans in the kingdoms of Naples and Sicily’, wrote Gibbon, ‘is an event most romantic in its origin, and in its consequences most important both to Italy and the Eastern empire.’83 Only a few generations after Rollo and his Vikings had settled in northern France, the Christian and French-speaking Duchy of Normandy had become a European power. In 1066 Rollo’s great-great-great grandson, William, defeated King Harold of England at the Battle of Hastings and secured his claim to the English throne.

Unlike the Norman conquest of England, the Norman incursion into southern Italy was a private initiative taken at a shrine to the Archangel Michael on Monte Gargano which juts out into the Adriatic Sea in Apulia – the spur, as it were, of the Italian boot. Here, early in the eleventh century, a group of Norman pilgrims met a Greek exile from the nearby city of Bari, then held by the Byzantine Empire. He persuaded them to take up his cause. Returning to Normandy, the pilgrims recruited an army of adventurers who crossed the Alps disguised as pilgrims and, though they failed in their assault on Bari, became a formidable band of mercenaries much in demand by the conflicting powers in the bottom half of the Italian peninsula – their courage, energy, aggression and fighting skills leading them to overwhelm, time and again, the considerably larger forces deployed against them by the Lombard dukes of Naples, Salerno and Benevento or the agents of the emperors in Constantinople.

To the tough northerners, these rich territories ruled by ‘effeminate tyrants’ were ripe for the taking; and over a few decades they established their dominance over southern Italy with only the coastal cities remaining in Byzantine hands. After at first assisting the Byzantines in their attempts to reconquer Sicily from the Muslims who had held it now for two hundred years, the Normans made the project their own. The extended family from the minor Norman nobility, the Hautevilles, gained ascendancy over their fellow barons. In 1060, Roger Guiscard captured Reggio and Messina on the coast of Sicily and, after thirty years of fighting against the Muslims, subdued the entire island; while on the Italian mainland the cities of Bari and Salerno fell to his brother Robert.

The popes in Rome were at first alarmed by the rise of these Norman states and in 1053 Pope Leo IX led an army against them which was defeated at the Battle of Civitate. Pope Leo was taken prisoner but was well treated by the Normans because the crown they coveted was within his gift. Seeing an advantage in a power that might counterbalance that of the German emperors, the policy of the popes was reversed. Pope Nicholas II, advised by Hildebrand, the future Pope Gregory VII, invested the Normans with their principalities in Apulia and Sicily in return for the recognition of his overall suzerainty and a promise of military assistance. Pope Alexander II, again on Hildebrand’s advice, sent banners and granted indulgences to Norman and French knights fighting against the Muslims in Sicily and Spain. The policy bore fruit when the Normans under Robert Guiscard saved Hildebrand from the army of the German Emperor, Henry IV. However, the Normans so antagonised the citizens of Rome that the Pope had to flee from the city to Monte Cassino and then Salerno where he died, insisting that he died in exile only because he had ‘loved justice and hated iniquity’.

* * *

Hildebrand’s claims to an overall authority over secular as well as spiritual powers for the office of pope brought with it a sense of responsibility for the fortunes of Christendom; and one of his unfulfilled ambitions was the dispatch of a Christian army against Islam. Until now, the Saracen threat had been sufficiently close to Rome for the popes to leave the Byzantines to fight the war on the eastern front. There was, moreover, both an endemic rivalry with, and contempt for, the Byzantine Greeks. It was not just the propensity of Byzantine emperors to put out the eyes of their rivals that affronted the Catholic Christian; the popes themselves had resorted to barbarities of the same kind. But the Greeks were seen as a treacherous people corrupted by the decadence of the East. The Byzantine emperors employed eunuchs not simply as guardians of their wives, but as high officials in both Church and state: only four offices were denied to them, and ‘many an ambitious parent would have a younger son castrated as a matter of course’.84 The Italian bishop Liudprand of Cremona who was sent on a diplomatic mission to Constantinople by the western Emperor Otto I, described it as ‘a city full of lies, tricks, perjury and greed, a city rapacious, avaricious and vainglorious’; but in all these western judgements of the Byzantine capital there was no doubt a measure of resentment at the Byzantines’ arrogance, and envy of a metropolis that surpassed Rome in size and splendour, had never been sacked by a barbarian army and, for all the occasional cruelty employed in the exercise of power, was a deeply religious society in which intellectual skills were highly esteemed and illiteracy among the middle and upper classes virtually unknown.

In other words, the Eastern Empire, despite its susceptibility to Oriental influences, had kept more of the strengths of the unified Roman state of antiquity than had the empire in the west. It had retained a salaried civil service and a disciplined, professional standing army. Unlike the ad hoc armies of unruly individuals found in western Europe, gathered for limited periods in accord with feudal custom, the regular units of the Byzantine army could be trained to respond to complex commands of a strategist trained in military science. The world’s best-run state had at this time its most efficacious army.

Grave differences had arisen between the eastern and western branches of the Christian Church on issues such as the primacy of the two patriarchal sees, the religious allegiance of newly converted peoples such as the Bulgarians, and on doctrine – not just the notorious filoque clause in the Creed that remains esoteric to all but the most erudite theologians, but, more significantly, on the veneration of images or icons of Christ and the saints. In the eighth century, the eastern emperors had moved towards the Muslim position that the veneration of icons was indistinguishable from the worship of graven images and should therefore be forbidden. The subsequent controversy led to a century of violence and persecution: the popes in Rome had condemned iconoclasm which, if it had triumphed throughout Christendom, would have killed in embryo the pictorial art that was to be one of the finest manifestations of Western civilisation – there would have been no Fra Angelico, no Raphael, no Leonardo da Vinci. None the less, the conflict had adversely affected relations between the Greek and Latin branches of Christendom which reached their nadir with the exchange of anathemas and excommunications in 1054.

However, when it came to the endemic conflict between Byzantium and Islam, there was never any doubt that Latin loyalties lay with their fellow Christians in the east. For a time, after the first wave of Muslim conquest, a frontier had been established between the Byzantine Empire and the Abbasid calpihate of Baghdad in the Taurus Mountains above Antioch in the southern corner of Asia Minor. In the early tenth century, under two Armenian generals, the imperial forces embarked upon a campaign of reconquest which led to the recapture of Cyprus and northern Syria including the city of Aleppo. Although Jerusalem still remained in the hands of the Fatimid caliphs who ruled from Cairo, the much larger city of Antioch, also the seat of a patriarch, was back in Christian hands. By 1025, the Byzantine Empire stretched from the Straits of Messina and the northern Adriatic in the west to the River Danube and Crimea in the north, and to the cities of Melitine and Edessa beyond the Euphrates in the east.

However, this military supremacy was not sustained. Internally, a social shift in favour of the great landed magnates of the Empire had led to the disappearance of the class of smallholders in Anatolia who had hitherto provided troops for the Byzantine army, and consequently to an increasing reliance on mercenary troops; and externally there appeared on the eastern frontiers of the Byzantine Empire a new wave of Islamic conquerors, the Seljuk Turks.

* * *

The Seljuks were a tribe of nomadic marauders from the steppes of Central Asia who in the tenth century had conquered the territory of the Baghdad caliphate and, embracing Islam, proclaimed themselves the champions of the Sunni Muslims. Further waves of related Turkoman tribesmen, inspired by the same mix of religious zeal and love of plunder as the Arab founders of Islam, approached with predatory intent the eastern frontiers of the Byzantine Empire.

In 1071 under their Sultan Alp Arslan, the Seljuks came up against an enormous Byzantine army at Manzikert near Lake Van in Armenia composed largely of mercenaries that had been assembled by the Emperor, Romanus IV Diogenes. The Byzantines were defeated, the Emperor himself taken prisoner by Alp Arslan. Nothing now stopped the Turkish advance: the Turkoman tribes swept across Asia Minor and by 1081 had taken Nicaea, less than a hundred miles from Constantinople, and established a province in Asia Minor which, because it had formed part of the Roman Empire, was called the Sultanate of Rum.

The strength of the Byzantines had been sapped by their need to fight a war on a second front. In the same year as the Battle of Manzikert, Bari, their last stronghold in Italy, had fallen to the Normans from Sicily under Robert Guiscard who had then crossed the Adriatic, taken the port of Dyrrhachium, and planned an advance towards Thessalonika. The Byzantines were powerless to resist them. Asia Minor, now held by the Seljuk Turks, had been their main source of corn and had provided half their manpower. The once mighty Eastern Empire had been reduced to a small Greek state facing annihilation. In this crisis, the Byzantines had the good sense to elevate their ablest general, Alexius Comnenus, to the imperial throne. Providence also came to their assistance with the deaths of the Normans’ leader, Robert Guiscard, and the Seljuk Sultan, Alp Arslan. None the less, the Byzantines’ predicament remained acute and so the Emperor Alexius appealed to his fellow Christians in the West.

Alexius’s first approach to Western Christendom was to Robert, Count of Flanders, who around 1085 had sent a small contingent of knights to Constantinople. It was perhaps Robert who advised Alexius that the Pope now carried greater weight in western Europe than the western Emperor, and in the spring of 1095 Byzantine delegates arrived at the Church Council being held at Piacenza in northern Italy.

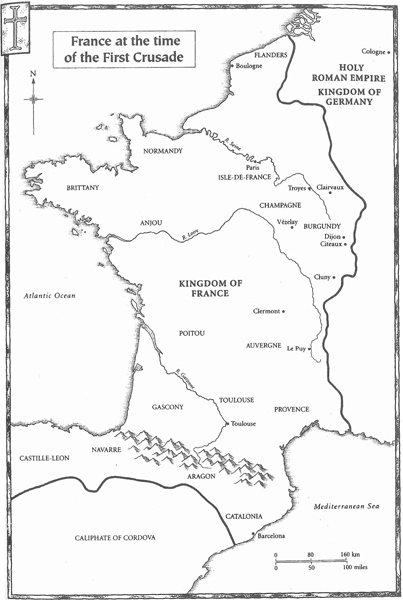

The Pope who presided over the Council of Piacenza was a Burgundian called Odo of Lagery, the son of a family of minor Burgundian nobility living in Châtillon-sur-Marne. His background was therefore the same as the leaders of the Cluniac reform, and his upbringing, too, had imbued him with religious zeal. He was taught at the cathedral schools in Rheims by the exceptional Bruno who in 1084 had founded a community of monks at a remote spot in the Alps near Grenoble, the mother house of the Carthusian order, La Grande Chartreuse. Odo of Lagery had been ordained priest at Rheims, and had risen through the ranks of the archiepiscopal administration to become archdeacon of the cathedral; but then in 1070 had left the regular clergy to become a monk at Cluny. For a time he served as prior under the Abbot Hugh, but was subsequently called to Rome where Hildebrand, then Pope Gregory VII, appointed him Cardinal-Bishop of Ostia. In 1088 he was elected pope and took the name Urban II.

A courteous, conciliatory and good-looking man, Urban shared the same high estimate of his office as his mentor, Gregory VII, but was far more tactful in the exercise of his authority in the difficult circumstances of the time. His policy of conciliation extended to Byzantium: in 1089, at the Council of Melfi, he had raised the ban of excommunication on the Emperor Alexius and had been rewarded with equally conciliatory moves in Constantinople. The rapprochement encouraged Alexius to appeal to the Latin Church for aid. His ambassadors were admitted to the Council at Piacenza and the Council fathers listened to their eloquent depiction of the suffering of their fellow Christians in the East. At the close of the Council, the bishops dispersed with a clear understanding of the threat posed by the infidels’ advance; while Urban II, as he moved on to France, carried with him the full burden of his personal responsibility as the Prince of the Apostles for the fate of Christ’s universal Church.

* * *

Having crossed the Alps, Urban II went first to Valence on the Rhône, then on to Le Puy where another aristocratic prelate, Adhemar of Monteil, was the bishop. Adhemar had been on pilgrimage to Jerusalem some years before and could give the Pope the benefit of his experience. From Le Puy, Pope Urban summoned the bishops of the Catholic Church to meet him at Clermont in November of the same year. He then travelled south to Narbonne, only a hundred miles or so from Christendom’s western front on the other side of the Pyrenees. He was now in Provence, then ruled by an experienced campaigner against the Saracens in Spain, Raymond of Saint-Gilles, Count of Toulouse and Marquis of Provence. From Narbonne, Urban II moved east along the coast of the Mediterranean to Saint-Gilles on the estuary of the Rhône, then north again up the Rhône valley to Lyons which he reached in October. From Lyons he moved on to Cluny in Burgundy where he had once been prior, and consecrated the high altar of the great church that for many years was to be the largest in western Europe. From Cluny he continued north to Souvigny to pray at the tomb of the abbot, Mayeul, who had been kidnapped by the Saracens as he crossed the Alps in the previous century, had refused the papal tiara, and was now acknowledged as one of the holiest of the abbots of Cluny.

What were Urban’s thoughts as he prayed at Mayeul’s tomb? No doubt, he felt that something must be done to aid the Byzantine Empire in its struggle against the Seljuk Turks. But there was also a pressing interest of the Western Church – the free passage of pilgrims to the Holy Land. For many centuries now, pilgrimage had been an integral part of the devotional life of the Christian. Every year, many thousands travelled across Europe to pray at favoured shrines – of Michael the Archangel on Mount Gargano which drew the Norman knights to southern Italy; of the apostle James at Compostella at Galicia in north-western Spain, sometimes starting at the Abbey of Vézelay in Burgundy which housed the relics of Mary Magdalene, or at the Abbey of Cluny itself. Or they went to Rome to pray at the tombs of the apostles Peter and Paul: as we have seen, it was a party of Anglo-Saxon pilgrims who were hacked to pieces when marauding Saracens made their attack on Rome in the ninth century.

However, the prize destination for all pilgrims was the Holy Land – the ground trodden by God made Man, his home town of Nazareth, his birthplace of Bethlehem, and above all the site of his resurrection from the dead, the Church of the Holy Sepulchre in Jerusalem. The journey was an expensive and hazardous undertaking. The easiest way to travel to Palestine was by sea in a vessel of the Amalfi merchants but that ran the risk of piracy and shipwreck. The journey by land was made easier with the conversion of Hungary to Christianity in the early years of the eleventh century; and, until the Seljuk invasion, the 1,500-mile route across the Byzantine Empire from Belgrade to Antioch was relatively secure; but once entering Islamic Syria, the Christian could be subject to harassment and onerous tolls.

None of this deterred the pilgrims, to whom the very hazards and suffering incurred on their journey were part of the point. For many, ‘pilgrimage was a form of martyrdom’85 that would ensure the salvation of the pilgrim’s soul. Sometimes it was imposed as a form of penance that would atone for the most serious sins; ‘the most important expression of the renewed spirituality in the eleventh century – which originated in Cluny – was the penitential pilgrimage’;86 and one finds some of the most notorious villains of the period such as Fulk Nerra of Anjou or Robert the Devil, Count of Normandy, going to Jerusalem to escape divine punishment for their crimes – Fulk, like Chaucer’s Wife of Bath, three times.

Such penitenital pilgrimages were encouraged and organised by the Church. The monks of Cluny presented the pilgrimage to Jerusalem as the climax to a man’s spiritual life – a severing of the ties that bound him to the world, with Jerusalem the Holy City as an antechamber to the world to come. Just as the good Muslim was obliged to go on pilgrimage to Mecca at least once in his lifetime, so the ambition of many a pious Christian was to touch Christ’s Holy Sepulchre before he or she died. ‘In fact the attitude of the eleventh-century Christians towards Jerusalem and the Holy Land was obsessive.’87

On the whole, in the course of the four centuries during which Palestine had been ruled by the successors of the Prophet, access to their sacred shrines had been allowed to the Peoples of the Book. The only outright persecution of Christians had taken place at the start of the eleventh century during the reign of the fanatical Egyptian Caliph, al-Hakim, who had ordered the destruction of all Christian churches in his domain, among them the Church of the Holy Sepulchre in Jerusalem; but his successor had permitted it to be rebuilt. However, only thirty years or so before the moment when Pope Urban knelt at the tomb of Abbot Mayeul, the Archbishop of Mainz, together with the bishops of Utrecht, Bamberg and Ratisbon, had led a group of seven thousand pilgrims from the Rhine to the Jordan which, when ambushed by a party of Muslims near Ramleh in Palestine, had been obliged to fight in self-defence.

A further consideration that may have been in the mind of Pope Urban, although this has never been established and remains essentially a matter of conjecture, was the need to find an outlet for the surplus energies of the Frankish warrior class. Coming from this background, Urban II was well acquainted with the problem posed by quarrelsome knights whose only talent was their skill with the lance and the sword. Descended from the battle companions of the Merovingian and Carolingian kings, they were now a distinct caste in society – a military elite. But the cost of the necessary equipment for a knight was considerable – the chain-mail tunic, shield, sword, lance, steel cap and horse. Although some customs and precedents from the barbarian past mitigated the rule of force, most disputes were settled with the sword. The raid on a neighbour’s crops and livestock was as common to the Christian knights of the Middle Ages as it was to the Arab tribes prior to the advent of Muhammad. ‘Violence was everywhere, impinging on many aspects of daily life.’88 Even when differences were brought before a court, they often let God settle the matter by way of a duel or trial by ordeal.

To limit the endemic conflict between the different groups among Christendom’s rapacious nobility, and in particular to keep its hands off the property of the Church, popes and bishops had tried to impose its usual sanctions of interdict (a ban on Mass and withholding the sacraments) and excommunication (expulsion from the Church); but also, more recently, the concept of a ‘Truce of God’ – the designation of certain holy days or penitential times of year such as Lent when fighting was forbidden. However, this device had been only partially successful. Western Christendom remained scandalously afflicted by fratricidal strife. How much wiser if a lesson could be learned from the example of Normans like the Hautevilles whose aggression had been channelled into conquering new kingdoms at the expense of Islam.

With such thoughts in his mind, Pope Urban II rose from the tomb of the Abbot Mayeul and turned south towards Clermont to meet the three hundred or so bishops who had obeyed his summons. From 19–26 November the Council, meeting in the cathedral, passed a number of decrees against the usual abuses of lay investiture, simony and the marriage of priests. King Philip of France was excommunicated for his adulterous liaison with Bertrada de Montfort and the Council endorsed the idea of a Truce of God.

On Tuesday, 27 November, the Council fathers were summoned to meet in a field outside Clermont’s eastern gate for a session that was open to the public. Here the papal throne had been set on a platform to enable Pope Urban II to address the huge crowd that had gathered to hear what he had to say. Although the accounts of his speech were written after the event, and were possibly coloured by what it inspired, it appears that the Pope first told of the reverses of the Byzantine Christians in the East and the suffering they had endured at the hands of the Seljuk Turks; then went on to describe the oppression and harassment of Christian pilgrims to the holy city of Jerusalem, conjuring up images of Zion that would have been wholly familiar to his audience from the constant singing of the Psalms. With the winning eloquence and genuine fervour of an experienced preacher, he reminded his audience of the example set by their ancestors under Charlemagne. He exhorted them to stop fighting one another for base motives of vengeance and greed, and to turn their weapons instead on the enemies of Christ. He in his turn, as the successor to Saint Peter with his God-given powers to ‘bind and loose’ on this earth, promised that those who committed themselves to this cause in a spirit of penitence would be forgiven their past sins and earn full remission of the earthly penances imposed by the Church.

Urban’s appeal was received with enthusiastic cries of ‘Deus le volt’ – ‘God wills it’ – and, in a dramatic gesture that had almost certainly been rehearsed by the two church leaders, Adhemar of Monteil, Bishop of Le Puy, went down on his knees before the Pope and asked to be allowed to join this Holy War.89 A cardinal in the Pope’s entourage also fell to his knees and led Urban’s audience in the Confiteor, the confession of their sins, after which the supreme pontiff granted absolution.

One twentieth-century writer has described Pope Urban’s appeal as a ‘combination of Christian piety, xenophobia and imperialistic arrogance’.90 Others have suggested that, in proclaiming Jerusalem as the crusade’s objective when Emperor Alexius’s appeal had been for military assistance in Anatolia against the Seljuk Turks, the Pope was taking advantage of the ignorance and gullibility of his flock. However, it is clear that spin doctors are not an invention of the late twentieth century: already at the Council of Piacenza, the ambassadors of the Emperor Alexius had played up the plight of Jerusalem precisely because ‘it would prove an effective propaganda slogan in Europe’.91 Moreover, the Pope’s objective was ‘the defence of Christians wherever they were being attacked. “For it is not service to liberate Christians from the Saracens in one place and to deliver them in another to Saracen tyranny and oppression.”’92

Did the Pope have any qualms of conscience about the use of violence? In the early Church, Jesus’s injunction to turn the other cheek had on the whole been taken at face value and violence was therefore deemed sinful in any circumstances. It was Augustine of Hippo who considered it justified in legitimate defence, and his teaching, scattered through a number of his works, had been assembled in the eleventh century by Anselm of Lucca. It had been absorbed into papal thinking during the pontificate of Gregory VII in relation to the reconquest of Sicily and Spain; and, indeed, at the news of the Byzantine defeat at Manzikert when in the name of the apostle Peter he twice appealed to the faithful to sacrifice their lives to ‘liberate’ their brothers in the east.

Now Augustine’s teaching was attached to the concept of a penitenital pilgrimage, making the ‘culminating surge towards the Holy Land of a cult of the Holy Sepulchre which had regularly spawned mass pilgrimages to Jerusalem throughout the eleventh century…’93 The pilgrims would be armed to ensure, in the words of Pope Urban, that the Saracens ‘would not further grind under their heels the faithful of God’. The indulgences he promised, and privileges granted to the crusaders, were almost indistinguishable from those given to pilgrims: ‘when the march began it seemed … to belong entirely to the traditional world of the pilgrimage to Jerusalem’.94

In this the Pope, true to his Cluniac vocation, showed that he was as interested in what the crusade could do for the crusader as in what the crusader could do for ‘the Asian Church’. He frequently referred to Christ’s injunction, which would have been familiar to all who heard him, to abandon wives, families and property for his sake, take up their cross and follow him. To give substance to the symbol, cloth crosses were distributed at Clermont to all those who vowed to go on crusade. These were sewn on to their surcoats at the shoulder not simply to signify this holy commitment, but also to show that the crusader was entitled to certain legal privileges and exemptions. The crusader’s family and possessions were to be protected by the Church. He was exempt from taxes and granted a moratorium on his debts. In return, he was expected to fulfil his obligation: the man who reneged on his vow was subject to automatic excommunication.

Although, as we have seen, precedents had been set in Sicily and Spain for a holy war fought by Christians against Muslims, it is clear that the appeal made by Pope Urban at Clermont was seen as momentous, ‘a shock to the communal system’ and ‘something different from anything that had been attempted before’.95 To Urban’s consternation, the most immediate and radical response was not among the class of knights that he had in mind, but among the poor. While Urban continued on a preaching tour of France, steering clear of the territories controlled by the French King Philip whom the Council had condemned, a number of popular preachers ignited the excitable and idealistic riff-raff of northern Europe and formed an ill-armed and undisciplined army that set off without further ado to vanquish the Saracens and liberate Jerusalem.

Their leader was a charismatic preacher from Picardy known as Peter the Hermit who claimed to have had a letter from Heaven authorising the crusade. The bishops did what they could to deter the old and the sick, and specifically forbade monks and clergy from going on the crusade without the permission of their superiors; but the movement got out of control. The lure of adventure and promise of spiritual reward proved irresistible. As we can still see from the carved images in the statuary of medieval cathedrals, people lived in real fear of the torments of Hell. Here was a chance to wipe the slate clean. Married men were forbidden to leave without their wives’ permission, but many ignored the ban. One wife locked her husband in his home to prevent him hearing the preaching of the crusade, but when he heard through the window what was on offer, he jumped out and took the Cross.

The crusade got off to a catastrophic start. The forces led by Peter the Hermit and a knight called Walter Sans-Avoir passed through Germany and Hungary in reasonable order; but contingents of Germans under a priest called Gottschalk, and a minor baron, Count Emich of Leinigen, as they marched down the Rhine, attacked the Jewish communities they came across in cities such as Trier and Cologne. This was probably not the undisciplined rabble that was once supposed. ‘These armies contained crusaders from all parts of western Europe, led by experienced captains.’96 However, they were almost certainly unable to make a meaningful distinction between Muslims and Jews; would almost certainly have counted on pillage en route to finance the journey to Palestine; and could only conceive of the crusade in the familiar terms of a vendetta which obliged them to avenge the suffering of their fellow Christians in the East. In consequence, there followed a series of pogroms – massacres, forced conversions, and collective suicide by the Jews in sanctification of their faith (kiddush ha-shem) like that of the zealots in Masada twelve centuries before.

Earlier in the century, the Church had clearly been aware of the danger posed to Jewish communities in circumstances of this kind: Pope Alexander II had written to the bishops of Spain ordering them to protect the Jews in their diocese ‘lest they be killed by those who are setting out to fight against the Saracens in Spain’.97 Now, in some German cities, the Prince Bishops and local nobility took the Jews under their protection and the clergy threatened the miscreants with excommunication. To little avail. In Mainz, the Christian chronicler, Albert of Aix, describes how the would-be crusaders,

having broken the locks and knocked in the doors … seized and killed seven hundred who vainly sought to defend themselves against forces far superior to their own; the women were also massacred, and the young children, whatever their sex, were put to the sword. The Jews, seeing the Christians rise as enemies against them and their children, with no respect for the weakness of age, took arms in turn against their co-religionists, against their wives, their children, their mothers, and their sisters, and massacred their own. A horrible thing to tell of – the mothers seized the sword, cut the throats of the children at their breast, choosing to destroy themselves with their own hands rather than to succumb to the blows of the uncircumcised.98

The atrocities were not confined to the Rhineland: in Speyer, Worms, and as far away as Rouen in the west and Prague in the east, the crusaders fell on the Jews. No doubt, the religious zeal of the murderous mob ‘was merely a feeble attempt to conceal the real motive: greed. It can be assumed that for many crusaders the loot taken from the Jews provided their only means of financing such a journey.’99 Nor were the Jews the only victims of their criminality: in Hungary the predatory rabble set about plundering the local inhabitants and were all massacred in their turn. Albert of Aix later wrote that this was believed by many Christians to be God’s punishment of those ‘who sinned in his sight with their great impurity and intercourse with prostitutes and slaughtered the wandering Jews … more from avarice for money than for the justice of God’.100

Meanwhile, the force led by Peter the Hermit and Walter Sans-Avoir had reached Constantinople escorted by the cavalry of the recently conquered Pechnegs whom the Emperor Alexius used as military police. Although advised to await the rest of the crusading army, Peter’s followers grew restless and started to ravage the suburbs of the city. Alexius arranged for their transfer across the Bosphorus and billeted them in a military camp close to the territory controlled by the Seljuk Turks. A successful raid by a French contingent encouraged some Germans to follow suit. When trapped by the Turks, the main force went to rescue them and was annihilated by the Turks on 21 October 1096. This marked the ignominious end of the ‘People’s’ Crusade.

* * *

Two months after the rout of this undisciplined vanguard at Xerigordon in the vicinity of Nicaea, the first contingents of the kind of army that Pope Urban had envisaged began to assemble at Constantinople. First to arrive was Count Hugh of Vernandois, a cousin of the King of France, who had come by sea with a small group of knights and men-at-arms. On 23 December, a far larger force arrived led by Godfrey of Bouillon, Duke of Lower Lorraine; his brothers Eustace, Count of Boulogne, and Baldwin of Boulogne; and their cousin Baldwin of Le Bourg.

Descended on both sides of their family from Charlemagne (and, according to later legend, from a swan), these four were classic exemplars of Frankish warrior-champions of the Church. Their retinue embodied the diversity of the old Frankish empire with both German-speaking and French-speaking knights. Godfrey had held the dukedom of Lower Lorraine under the Emperor Henry IV, but the fact that he sold all his estates and his castle at Bouillon to finance his participation in the crusade suggests that he did not mean to return home; though whether his objective was an eastern principality or the crown of martyrdom remains unclear.

Next came a contingent of Normans from southern Italy led by the forty-year-old Bohemond of Taranto, the eldest son of Robert Guiscard. Here there was less ambiguity: the Norman record suggested that they had predatory intentions and with good reason gave the Emperor Alexius some cause for disquiet. However, Bohemond had taken the Cross while besieging Amalfi with the outward signs of sincere conviction, personally handing out cloth crosses to those who wanted to join him. Among them was his dashing young nephew Tancred. With their contingent, they had crossed the Adriatic from Italy to Greece, and then had proceeded in good order to Constantinople.

The same route had been followed by a group of powerful nobles from northern Europe – Robert II, Count of Flanders, whose father had fought for the Emperor Alexius; Robert, Duke of Normandy, brother of the English King, William Rufus; and Stephen, Count of Blois, the son-in-law of William the Conqueror; while the largest contingent of all, Provençals and Burgundians under Count Raymond of Toulouse, took an intermediate route down the Dalmatian coast, then across from Dyrrhachium to Thessalonika and on to Constantinople. With him came Adhemar of Le Puy, appointed by Urban II as his legate and the spiritual leader of the crusade.

Adhemar’s influence was invaluable in settling the differences between the Frankish princes and negotiating the passage of the crusading army through the Byzantine Empire. The Emperor Alexius had not anticipated a force of this size and would only allow its leaders to enter Constantinople, keeping the troops outside its walls. In April 1097, the crusading army crossed the Bosphorus unopposed. The Turkish Sultan, Kilij Arslan, lured into a false sense of security by his earlier victory over the army of Peter the Hermit, attacked the crusaders outside Nicaea. He learned too late that he was up against something more formidable – the heavy cavalry made up of Western knights. Anna Comnena, the daughter of the Emperor Alexius, was to write in her memoir of her father that ‘the irresistible first shock’ of a charge by Frankish knights ‘would make a hole through the walls of Babylon’.101

The defeat of their sultan, followed by the investment of Nicaea not just by the Frankish army but also by a Byzantine fleet brought overland to the lake adjoining the city, led the Turkish garrison of Nicaea to surrender to the Byzantine admiral, Butumites. Although they had done a large part of the fighting, the crusaders kept the promises they had made to the Emperor Alexius to return his former possessions and remained outside while his troops entered the city. Although they were given gifts of considerable value, there was no question of the kind of plunder that a victorious army might have expected as the spoils of war.

However, their spirits were high. ‘Unless Antioch proves a stumbling block,’ Stephen of Blois wrote in a letter to his wife, ‘we hope to be in Jerusalem in five weeks’ time.’ But the going was harder than they had anticipated. They were unused to the heat of the Anatolian summer: there was a shortage of water and, since the Turks had scorched the earth in front of them, a lack of food as well. As they approached Dorylaeum, the vanguard made up of the Italian and French Normans, a Byzantine contingent and some Flemings was attacked by the army of Kirij Arslan. The Turks had learned from their experience of Nicaea and manoeuvred to avoid a frontal attack by the crusaders’ cavalry. Their mounted archers circled the crusaders. The Christian foot-soldiers were sheltered by the army of Bohemond and his knights who held firm until the rearguard under Godfrey of Bouillon, Raymond of Toulouse and Adhemar of Le Puy came to their rescue and routed the Turks. The Turkish camp, abandoned by the fleeing army, was taken by the crusaders and this time the booty was theirs.

After this second triumph the army resumed its march across Anatolia. Hunger and thirst continued to torment, and it had to fight two further battles before reaching a safe haven in the Christian kingdom of Cilician Armenia – an anomalous state in the south-east corner of Anatolia: Armenians had first been settled there by Byzantine emperors as a reward for military service, and had been joined by their compatriots ousted from the Armenian homeland near Lake Van by the Turks.

After a period of rest and recreation as guests of the Armenians at their capital of Marash, the crusading army, led by Adhemar of Le Puy, came down from the hills, fought its way across the River Orontes and on 21 October 1097 reached the city of Antioch. Antioch was a daunting sight – a city almost three miles long and one mile deep, built half on the plain of the Orontes, half on the precipitous slopes of Mount Silpius with four hundred towers punctuating the walls built by the Emperor Justinian and reinforced by the Byzantines a hundred years before; and, at its highest point, a citadel a thousand feet above the town. It had been one of the major metropolises of the Roman Empire and remained not just the strategic key to the whole of northern Syria but a rich and powerful principality in itself, still with a largely Christian population but garrisoned by the Turks who had captured it from the Byzantines twelve years before.

The Latin leaders could not agree upon whether to attempt to storm the city or to wait for reinforcements. Taking advantage of the crusaders’ hesitation, the Turks made sorties, attacking the groups sent out to forage for food. The siege dragged on. Cold, wet and hungry, the Christian army found its morale declining to the point where the crusaders began to wonder whether God had not abandoned them as punishment for their misdeeds. Having already lost a large number of their horses and mules on the march across Anatolia, so that three-quarters of the knights had to travel on foot, they now ate those that remained to stay alive. The price of food brought from Armenia made it accessible only to the rich: some impoverished Flemings who had followed Peter the Hermit, known as Tafurs, ate the Turks they killed. ‘Our troops’, wrote Radulph of Caen, ‘boiled pagan adults in cooking pots: they impaled children on spits and devoured them grilled.’102 In January 1098, Peter the Hermit was caught by Tancred trying to desert and forced to return. In February, the Byzantine contingent abandoned the siege. To make matters worse, news reached the crusaders that a large army was marching to the relief of Antioch led by Kerbogha of Mosul.

In this moment of crisis, Bohemond of Taranto showed his hand. He had a tame traitor inside Antioch but he wanted the other crusaders’ assurance that if he captured the city it would be his. The council of princes, overriding the objections of Bohemond’s chief rival, Raymond of Toulouse, agreed. Sensing that the city’s surrender was imminent, Stephen of Blois left for home. On the same day, the rest of the crusading army feigned a retreat from the walls of the city but returned under cover of darkness and were let in by Bohemond’s spy. The city was taken. When Kerbogha of Mosul reached Antioch, the besiegers became the besieged but, inspired by the miraculous discovery beneath the cathedral of the Holy Lance that had pierced the side of Christ, they made a sortie that put the Saracens to flight.

Because it was thought inadvisable to continue towards Jerusalem in the heat of the summer, the crusading army remained in Antioch: the date for their departure was fixed for All Saints Day, 1 November. Meanwhile, the more adventurous set out to emulate Baldwin of Boulogne who earlier that year had established the first Latin state in the area at Edessa. Entering the city with a force of only eighty knights, he had been welcomed by the Armenian ruler, Thoros, and adopted as his son. However, Thoros was unpopular with his Monophysite subjects and only a month later, probably with Baldwin’s connivance, he was deposed and killed, leaving Baldwin the sole ruler of Edessa.

In July, Antioch was afflicted by the plague which on 1 August claimed the life of Adhemar of Le Puy. As Papal Legate and spiritual leader of the crusade, and with a wise and conciliatory nature, he had played an invaluable role in smoothing the ruffled feathers of the quarrelling and vainglorious princes. To escape the plague, many of them had left Antioch and the morale of the army again declined. The bad blood that existed between Bohemond and Raymond was reflected in a growing antagonism among their Norman and Provençal followers: a favourite gibe of the Normans was to say that the Holy Lance was a fake.

In September, after returning to Antioch, the princes wrote to Pope Urban asking him to come out in person to lead the crusade. The feast of All Saints came and went. Raymond at last agreed that Bohemond should keep Antioch on condition that he took part in the assault on Jerusalem. To this, Bohemond agreed; but apathy seemed to paralyse the leaders. There were weeks of procrastination. It was only at the insistence of an increasingly exasperated rank and file that the princes finally agreed to appoint Raymond of Toulouse their commander-in-chief.

The crusading army set out from Antioch on 13 January 1099, marching between the mountains and the Mediterranean coast. Most of the local emirs, rather than block their progress, preferred to pay protection to the advancing horde of monstrous Franj. The more significant powers in Damascus, Aleppo and Mosul watched and waited: it was not in their interest, as they saw it, to come to the aid of the Fatimid caliphs in Egypt who the year before had reoccupied Jerusalem.

On 7 June 1099, the crusading army struck camp before the walls of the Holy City. Although smaller than Antioch, and far less significant in political and strategic terms, Jerusalem had remained well fortified ever since the Emperor Hadrian had rebuilt the city. The Byzantines, the Ommayads and the Fatimids had all renewed its defences; and the Fatimid governor of the city, Iftikhar, had had ample warning of the crusaders’ approach. The Christian inhabitants had been expelled but not the Jews. The city’s cisterns were full of water and there were plentiful supplies of food, while the wells outside the city had been blocked or poisoned. The ramparts were manned by the garrison of Arab and Sudanese troops, and help had been summoned from Egypt.

Aware of their vulnerability to a relieving force, short of food and water, and lacking in heavy equipment such as towers and mangonels, the crusaders understood that they could not afford a protracted siege. Only one-third of those who had departed from western Europe two years before remained alive: discounting non-combatant pilgrims, among them women and children, this meant a fighting force of around twelve thousand foot-soldiers and twelve or thirteen hundred knights. They knew they could expect no help from the Byzantines: indeed, Emperor Alexius, instead of aiding them, was actually parleying with the Caliph in Cairo.

Providentially, ships from England and two galleys from Genoa had arrived at the port of Jaffa which the Muslims had abandoned. Their cargo supplied the army with food, and also nails and nuts and bolts. Tancred and Robert of Flanders went as far as Samaria to find suitable wood, returning with tree-trunks on the backs of camels. Carpenters from the Genoese galleys went to work constructing mobile towers, catapults and ladders to scale the walls.

On the night of 13 July the assault began. The first tower to reach the walls was that of Raymond of Toulouse but the defence of that sector was directed by the Muslim governor, Iftikhar, and the Provençals could not gain a foothold on the ramparts. On the morning of 14 July, Godfrey of Bouillon’s tower was brought up against the north wall, and around midday a bridge was made from its upper storey, from which Godfrey himself and Eustace of Boulogne directed the assault. First across the bridge were two Flemish knights, Litold and Gilbert of Tournai. Behind them came the leading knights of the Lotharingian contingent, followed closely by Tancred and his Norman knights. While Godfrey sent his men to open the gates to the city, Tancred fought his way through the streets to the Temple Mount which some of the Muslims intended to make their redoubt. Tancred was too quick for them. He took the Dome of the Rock and pillaged its precious contents and, in exchange for the promise of a considerable ransom from the capitulating Muslims, allowed them to take refuge in the al-Aqsa mosque, displaying his banner as a pledge of his protection.

Iftikhar and his bodyguard withdrew into the Tower of David which he subsequently surrendered to Raymond of Toulouse in exchange for the city’s treasure and a safe-conduct out of Jerusalem for himself and his entourage. Raymond accepted the terms, took possession of the citadel and escorted Iftikhar and his bodyguard out of the city. They were the only Muslims to escape with their lives. Intoxicated by their victory, and still charged with the passions of battle, the crusaders set about the slaughter of the city’s inhabitants with the same indifference to their victims’ age or sex as had been shown more than a thousand years before by Titus’s legionaries. Tancred’s banner on the al-Aqsa mosque was not enough to save those who had taken refuge inside. They were all killed. The Jews of Jerusalem fled to their synagogue for safety. The crusaders set it on fire: the Jews were burned alive.

Raymond of Aguilers, chaplain of Raymond of Toulouse, made no attempt to play down the horror of what he had seen when he subsequently described the capture of Jerusalem in his chronicle. When visiting the Temple Mount, he had walked up to his ankles in blood and gore. ‘In all the … streets and squares of the city, mounds of heads, hands and feet were to be seen. People were walking quite openly over dead men and horses.’ But to him, the Muslim defenders had only got what they deserved. ‘What an apt punishment! The very place that endured for so long blasphemies against God was now masked in the blood of the blasphemers.’

Muslim apologists were quick to point to the contrast between the savagery of the Franks and the courtesy and humility of the Caliph Umar when he had captured Jerusalem in 638: Christians would counter that the Byzantines had surrendered without a fight. But such polemic was to come later. Now there was only jubilation that Pope Urban’s mission had been accomplished, and the crusaders’ vows fulfilled. After three years of suffering and hardship, and a journey of two thousand miles, in savage climates and through inhospitable terrain, the pilgrims had reached their journey’s end. On 17 July, the princes, barons, bishops, priests, preachers, visionaries, warriors and camp-followers processed through the streets of the deserted city to the Church of the Holy Sepulchre. There they gave thanks to God for their extraordinary victory and celebrated the sacrifice of the Mass at the holiest shrine of their religion – the tomb from which Jesus of Nazareth, the living Temple of the New Covenant, had risen from the dead.