I ween that I hung on the windy tree,

Hung there for nights full nine;

With the spear I was wounded, and offered I was

To Odin, myself to myself

Runes are one of the most unquestionably Norse things in existence. These ancient symbols have carried some of the ideas, beliefs, and core concepts of the Norse peoples across space and time. On even deeper levels they are symbols endowed with hidden knowledge and great power. Since time immemorial, people have used the runes to read the patterns of fate and create potent magical workings. They are a key part of modern Norse Pagan practice as a part of ritual work, mysticism, and art.

The story of the runes begins with Odin and his endless hunger for knowledge. The Many-Named god was restless in pursuit of answers to every question, no matter how far he had to go to find them. His endless journey brought him to his greatest act since overthrowing Ymir. This chase ended at the World Tree, the heart of reality.

When he arrived, he found the right spot, prepared a rope, impaled himself with his own spear, and hanged himself from the World Tree as a sacrifice of himself to himself. There he remained, caught between life and death, for nine days and nights without food, drink, or rest. On the final day, he looked down and saw strange shapes pulsing with power hidden in the roots. Screaming, he snatched up the very first runes. Odin then shared this new knowledge with the world, giving some to the gods, some to the spirits, and some to humanity.137

Historically speaking, the first runes, known as the Elder Futhark, appear in what is today Germany around the first century CE as a simple system of writing. They remained in use for centuries. As time passed and people moved, the runes changed. One form took shape in Scandinavia, known as the Younger Futhark. The other major form traveled with the Anglo-Saxon people, becoming the Anglo-Saxon Futhorc.138

Somewhere along the way, each rune acquired unique meanings to go with their names and sounds. These meanings were recorded in rune poems, three of which survive to the present day. These sources, along with the tireless work of runologists, are the heart of what is known about the runes. Along with the lore, such knowledge is the foundation for modern uses of the runes by Norse Pagans around the world.

There are two main ways, along with writing and art, the runes are used in modern Norse-derived practice: divination and magic. Both methods use the same meanings for the runes. There are people who use runes only for divination, only for magic, both, and neither—how you use the runes in your practice is entirely up to you.

Divination

Also known as rune-casting, divination is the most well-known use of the runes. Like all forms of divination, rune-casting is useful for reflecting on your current circumstances, viewing them from a new perspective, and gaining unexpected insights. Some see it as a reliable method for reading the currents of Fate. Regardless of your perspective, it is very effective for finding new perspectives.

Historically speaking, the oldest known example of rune-casting comes from the second century CE via the Roman historian Tacitus. He described peoples in ancient Germania divining their future by drawing lots with pieces of cut wood. The medieval Christian monk Rimbert, while preaching in Sweden, described a ceremony where Pagan Swedes performed divination by casting lots with wooden chips soaked in sacrificial blood. Runic divination as is commonly practiced today was first popularized in 1983 when Ralph Blum published The Book of Runes.139

If you need medical, legal, academic, psychiatric, or any other professional assistance, rune-casting can be a useful tool but is never a replacement for such services. It is also best to ask someone else to conduct divination for you if your question concerns a matter where you have very strong feelings about the outcome or if you are facing an especially difficult question. This is because it is very easy to impose what answers you want to hear onto the runes; having someone else do it for you avoids this problem.

You can make your own runes or, if you prefer or are just starting out, purchase a set. If you choose to carve your own, wood and bone are some of the most popular choices thanks to how easy they are to work with. Some prefer ceramic, metal, or even stone runes. The choice of material is a matter of personal preference. What matters is you use the material that works best for you and isn’t too fragile or easily scratched. The runes should also have the same general shape—for example, all the runes in a set being shaped like discs or square tiles, so that you can’t easily tell them apart by touch.

There are two ways to cast the runes, known as drawing and throwing the runes. In both forms, the rune-caster begins by putting all of the runes in a pouch. The caster then asks the questioner to place their hand in the pouch and shuffle the runes while thinking about their question. It is best to not ask what their question is until after casting and reading the runes because the caster can focus on interpreting the findings rather than trying to fit what they see to the questioner’s desires.

When drawing runes, pull three runes from the pouch, one at a time without looking, and lay them out from left to right, reading them as past, present, and future. If there are any matters that need further explanation, you can draw a fourth rune and place it above the past, present, or future rune that is unclear. You can also lay out the runes in spreads and patterns used in tarot, substituting the cards for runes. Drawing the runes provides an orderly approach with some sense of consistency in readings, making it ideal for anyone who is new to rune casting.

Throwing the runes is a more intuitive approach that leaves a lot more to chance. In this form, after the questioner shuffles the runes in the pouch first. After they do so, the caster also shuffles the runes. After you have shuffled the runes, pull out as many as you feel should be in your hand without looking at them. Next, cup the runes in your hands, breathe onto them without looking to give the reading life, shake them like dice, and throw them onto a table, cloth, or other surface for reading. You then read the runes based on the patterns they make, where the runes fall, their proximity to each other, and the meanings of the runes themselves.

The shape the runes make and their relationships in space matter as much as what the runes themselves mean. This more intuitive style is less repeatable but can offer very profound, surprising insights. Throwing the runes is recommended for more experienced casters though if you feel like it’s a good fit for you then feel free to start out with throwing the runes instead of drawing them.

Regardless of the method used, rune-casting gives the caster and questioner a useful tool for reflecting on their circumstances. The information they provide is helpful because it provokes you to consider possibilities or perspectives that you may have ignored. They can also inspire you to seek out different solutions or approaches to resolving the challenges you face. Even if a specific rune-casting gives you a highly positive reading, this is as much an opportunity to re-examine what is around you and what might have been taken for granted.

Magic

In Radical Norse Paganism, the runes are more than just symbols representing specific concepts. They are the notes of the music uniting the Nine Worlds, given form by Odin’s sacrifice and their development over time. They are reflections of deeper, powerful concepts tied directly to the deepest workings of Fate and the societies who used them. When you use the runes in magic you are tapping into this deep well of meaning, unleashing forces with the power to change Fate.

There is a lot of evidence showing runes were used in ancient times for magical purposes. One of the best direct examples is from the Sigrdrifumal, where the Valkyrie Sigrdrifa tells the hero Sigurdr of different ways he can use runes to bring victory in battle, heal, and protect. In another example, the hero Egil Skallagrimson draws runes with his blood on a drinking horn to see if its contents are poisoned. Academic runologists also claim the meanings of the runes are evidence of magical use in ancient times, reinforcing other evidence showing their historical use for mystical purposes.140

There are three main forms of rune magic used in Radical Norse Paganism. These are drawing or carving runes onto objects, singing them, and bindrunes. Regardless of the method used, all runic workings draw their power from the meaning of the runes used. Runes can also be used, through these methods, to invoke the names of people, places, and Powers by spelling them out in runes.

Be careful when engaging in any kind of rune magic. The concepts you are invoking directly manipulate the forces of Fate. Your hamingja comes into play when you engage in any sort of runic magic, binding you to the working. This means you should beware the law of unintended consequences and any unexpected outcomes.

Always remember rune magic is not a replacement for engaging in all actions necessary for accomplishing your goals. A bindrune for protecting your home won’t do much good if you don’t lock the front door and performing galdr to get a better job won’t get any results if you don’t fill out some applications. Even though rune magic tilts the odds in your favor, you still need to place your bet and roll the dice.

In Radical Norse practice, you should always invoke fire and ice to charge a runic working. There are three ways to do this. The first is to use the method described in chapter four, which is just as effective for charging a space in preparation for a working as it is for ritual. The second method is good for workings on the fly: first, draw or visualize the runes isa and kenaz on the palms of your dominant and non-dominant hands, respectively, as you breathe in before clapping your hands together as you breathe out. You then use this energy to power a working. You can adapt this method using the base principles in a lot of ways, with it even being possible to get the same effect by drawing or visualizing the runes on a thumb and finger before snapping. The final approach, used for group workings and rituals, starts with dividing practitioners into two groups. One group chants “isa” while the other chants “kenaz” at the same time in a long, sustained tone.

The first and most basic method of magical use for runes is carving or drawing runes on objects. This imbues the object or place with the properties of the runes you inscribe. You can use this to invoke the power of one specific rune, several runes, or even use runes to call on a specific Power by inscribing its name in runes. You can also call on the power of the runes for a specific working or purpose, in the same way as inscribing them into an object, by drawing their shape in the air. When drawing runes, the order you draw or carve them in will influence how they manifest. A good first rune-carving is creating a set of divination runes. To do this, begin by laying out the material you will use for the divination runes, summon a charge, and then start carving.

The second form of runic magic is known as rune galdr, the art of the runic spell-song. To perform galdr, the first thing you need to do is take a deep breath in. Next you chant the name of the rune while visualizing its shape and concentrating on the purpose of the working. When you have finished chanting the rune’s name, expel all remaining breath to release it into the world. Rune galdr can be as simple or complex as necessary, using whichever and as many or few runes as needed. That said, like drawing or carving runes, the order you sing the runes shapes how the working will unfold. You could, if you so choose, pair the galdr with a melody and make it into a song. Rune galdr can be combined with drawing or carving runes, creating bindrunes, trance and even some forms of seidr magic. This gives such workings additional potency. This versatility makes runic galdr a highly effective form of rune magic.

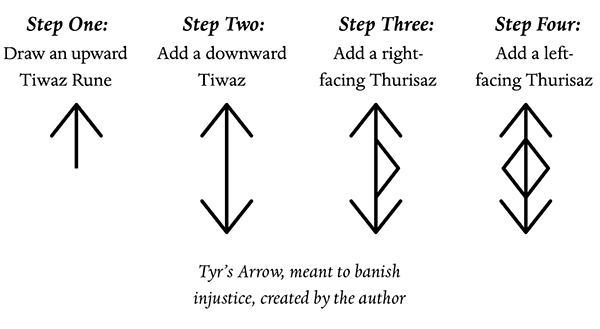

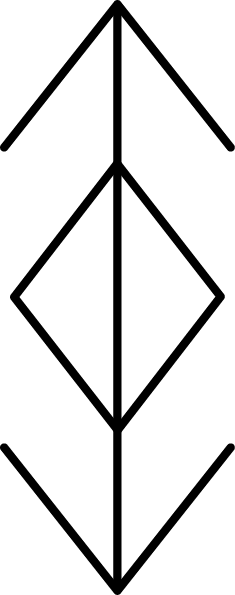

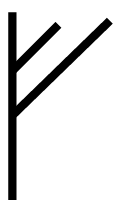

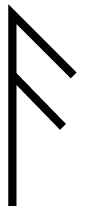

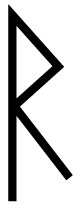

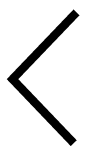

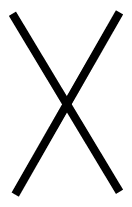

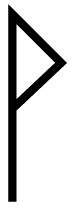

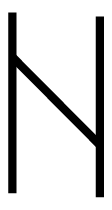

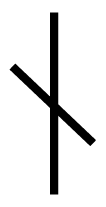

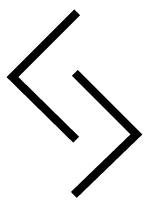

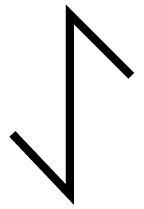

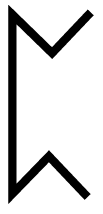

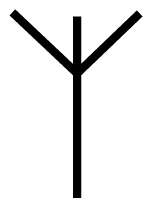

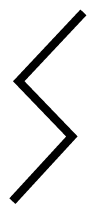

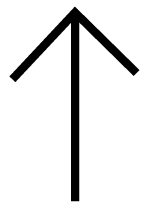

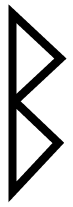

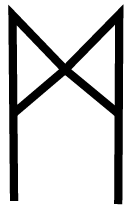

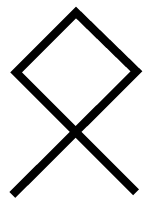

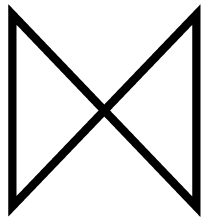

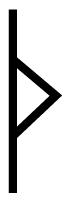

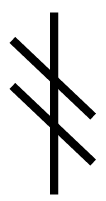

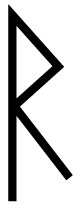

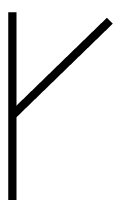

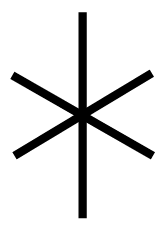

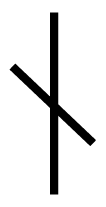

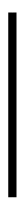

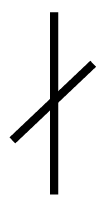

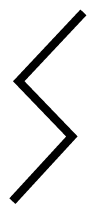

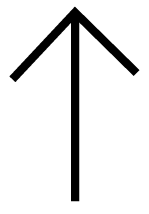

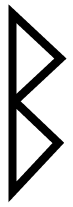

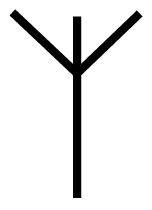

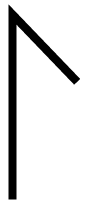

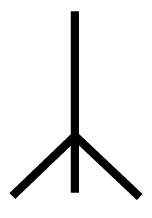

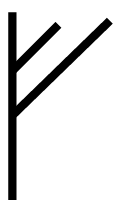

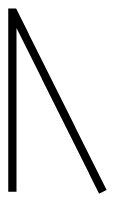

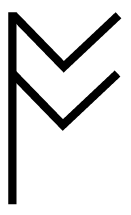

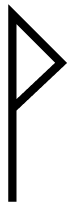

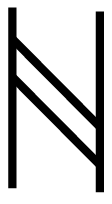

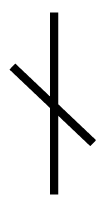

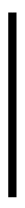

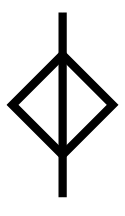

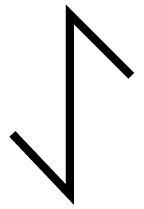

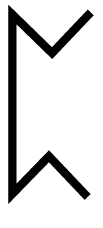

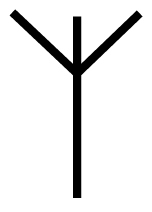

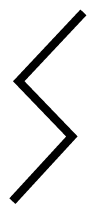

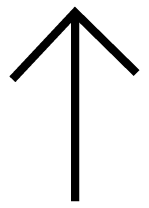

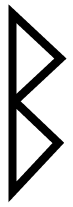

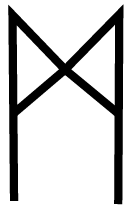

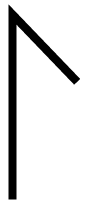

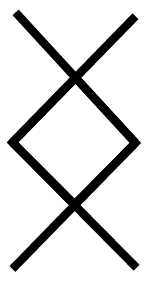

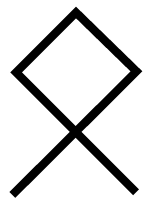

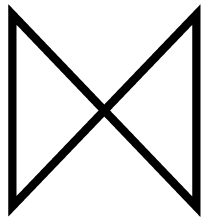

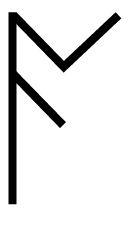

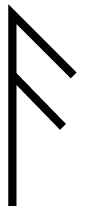

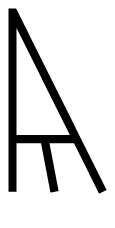

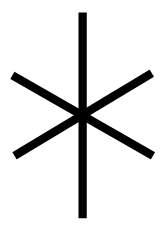

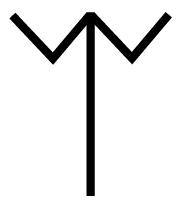

Bindrunes are the third form of runic magic. A bindrune is created by taking more than one rune (they can be from different runic alphabets), and combining them to make a single, new symbol. To make a bindrune, you first need to determine your intended purpose. Next, pick out the runes that will help achieve that purpose, such as using runes of stability, strength and endurance for a bindrune of protection. You then invoke fire and ice and start drawing the bindrune, using the chosen runes as the components for the design. If you want, you can galdr the runes you use as you draw the bindrune. When you are finished, take a deep breath in, place your drawing hand over the new bindrune, and expel all air from your lungs to release it into the world. Some examples are included on the next page. Here is an example of how to construct the Tyr’s Arrow bindrune, which is used to banish injustice:

As this example shows, bindrunes can be made using the same rune more than once. In the case of Tyr’s Arrow, the use of two bindrunes, Tiwaz and Thursiaz, twice each reinforces their energies. It also balances them, making the bindrune an equal mix of what each represents. Tyr’s Arrow combines all of this into the greater purpose of a working meant to secure and support justice. It is guided by the powers of Tiwaz and bolstered by the overwhelming force of Thurisaz. This also shows how a bindrune is a working that draws power from the runes used to make it and becomes greater than the sum of its parts.

Bindrunes, like drawing or carving runes, can be inscribed onto an object to grant it the bindrune’s power, drawn in the air or even summoned by runic galdr. Bindrunes are also be used to create personal or group symbols. Regardless, once a bindrune has been made it can be used by anyone who knows its shape and purpose. This means you can use already existing bindrunes for workings along with your own bindrunes.

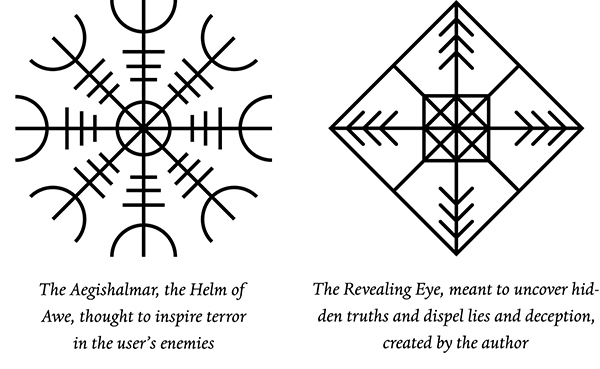

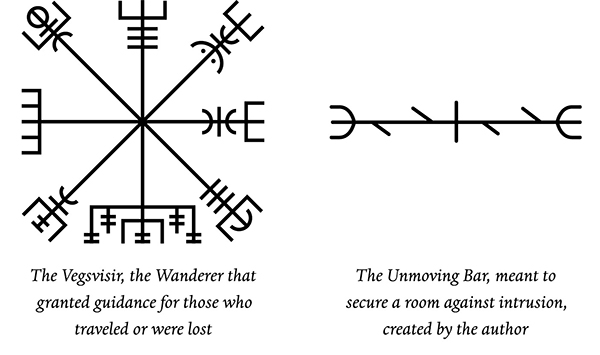

There are many bindrune-like symbols that appear in many different sources. Two of the most famous are the Aegishjalmer, the Helm of Awe, which is said to inspire fear in enemies and strength in those who wore it, and the Vegsvisir, the Wanderer, that was said to help guide travelers. There are many other similar symbols that survive in Icelandic grimoires, with The Sorcerer’s Screed as the most famous collection of such symbols.

Examples of Bindrunes

Tyr’s Arrow, meant to banish injustice, created by the author

The Elder Futhark

|

Symbol |

Name |

Sound |

Meaning |

|

Fehu |

F |

Wealth |

|

Uruz |

U |

Wild Ox, Auroch |

|

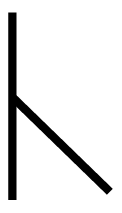

Thurisaz |

Th |

Giant |

|

Ansuz |

A |

god |

|

Raido |

R |

Riding, Ride |

|

Kenaz |

K |

Torch |

|

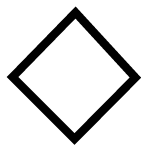

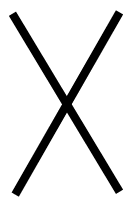

Gebo |

G |

Gift |

|

Wunjo |

W |

Joy |

|

Haglaz |

H |

Hail |

|

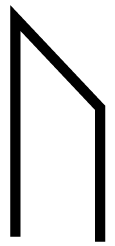

Naudiz |

N |

Need, Affliction |

|

Isa |

I |

Ice |

|

Jeran |

J |

Harvest |

|

Ihwaz |

Ae |

Yew |

|

Symbol |

Name |

Sound |

Meaning |

|

Perthro |

P |

Vessel |

|

Algiz |

Z |

Elk |

|

Sowilo |

S |

Sun |

|

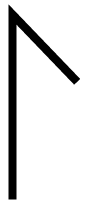

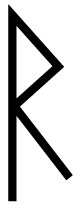

Tiwaz |

T |

Tyr |

|

Berkanan |

B |

Birch |

|

Ehwaz |

E |

Horse |

|

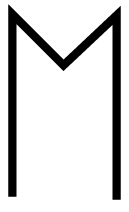

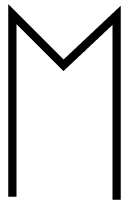

Mannaz |

M |

Human |

|

Laguz |

L |

Water |

|

Ingwaz |

Ng |

Ing, Fertility |

|

Othilan |

O |

Inheritance |

|

Dagaz |

D |

Day |

The Elder Futhark 141

The Elder Futhark is one of the most commonly used of the futharks thanks to its age, being popularized by authors like Ralph Blum, and how directly the runes correspond to most of the modern Latin-style alphabet. The names and meanings of each of these runes were determined by academic runologists through comparing the meanings described for the Younger and Anglo-Saxon Futhorc in their surviving rune poems.142

Fehu—Cattle, Liquid Wealth

Fehu is the rune of wealth. In all the rune poems, wealth is portrayed as a source of comfort and a cause of discord. Fehu as the rune of cattle represents liquid and portable wealth rather than invested or nonliquid wealth like property.

Uruz—Auroch, Strength, Labor

Uruz is the rune of the auroch, the prehistoric ancestor of modern cows. The auroch was larger, stronger, and more vicious than domesticated cattle, tying it to strength. It is also tied to labor, as the descendants of the aurochs were used in ancient times as beasts of burden.

Thurisaz—Giants, Danger, Overpowering Might

Thurisaz is the rune of the giant. In the rune poems, the meaning taken is one of the great power, danger, and fear inspired by giants. Giants are also powerful beings, suggesting this is a rune of overwhelming might with the risk of great danger.

Ansuz—Speech, Odin

Ansuz is the Odin rune and the rune of speech. The ties to Odin are shown in the Norwegian and Icelandic poems while speech is present in those and the Anglo-Saxon poem. When used, it can represent Odin, the power of speech, and impact of words.

Raid —Journey, Travel

—Journey, Travel

Raido is the rune of riding, traveling and the journey itself. The poems reference all these aspects, making Raido a potent symbol of movement through the world. It can represent journeys of all kinds, physical and otherwise.

Kenaz—Fire, Light, Ill-Tidings

Kenaz is a more complex rune. In the Norwegian and Icelandic poems, it is the rune of the boil, a symptom of serious illness. In the Anglo-Saxon poem it is the rune of the torch, light, and flame. What meaning Kenaz takes depends heavily on how and where it is used.

Geb —Gifts, Exchange

—Gifts, Exchange

Gebo is the rune of the gift, but its meaning is different from the modern concept. In the ancient world, gift-giving was seen as part of a reciprocal exchange where any who receive gifts were expected to give in exchange. This makes Gebo a rune of exchange, where a gift requires a gift in turn.

Wunj —Joy, Pleasure, Lust

—Joy, Pleasure, Lust

Wunjo is the rune of joy and pleasure. It also has overtones of lust in some poems, tying it to joy and pleasure, but it can also inspire greed and possessiveness. Wunjo’s meaning is therefore dependent on context and circumstances.

Haglaz—Chaos, Upheaval, Opportunity

Haglaz is the rune of the hailstone. It has implications of disaster, chaos, and upheaval. However, the disruption of Haglaz brings the potential for future growth. Whether it is an omen of growth through struggle or destruction depends on how it appears.

Naudiz—Binding, Fate, Necessity

Naudiz is the rune of necessity and fate, with connotations of binding or deep ties. Which meaning it carries depends on how it appears in readings or magical uses. Regardless of which aspect is present, Naudiz should always be heeded.

Isa—Ice, Order, Stasis

Isa is the rune of ice. It represents all that ice is, from a more static form of water to a slow-moving bringer of change. Isa’s meaning depends on how you see it appear, with possible meanings including preservation, stagnation, and slow change. It can also have connotations of an unexpected path or new opening as suggested in the Norwegian and Icelandic rune poems.

J ran—Year, Harvest

ran—Year, Harvest

Jeran is the rune of a good year and harvest. It represents work coming to fruition, the results of earlier work. Based on the good year meaning, this is a generally positive rune, though it is key to remember what you plant is what you will pluck.

Ihwaz—The Center, Endurance, the Yew

Ihwaz is the rune of the yew tree. In the poems the yew is referred to as being tough, difficult to burn and green in winter. Ihwaz is a rune of endurance and a strongly rooted center, suggesting a point of strength and the qualities needed to persevere.

Perthro—Vessel

Perthro’s meaning is not directly given but is hinted at in the Anglo-Saxon rune poem. It refers to Perthro as a source of amusement for the great and something warriors sit around in a hall, suggesting it represents a vessel for food or drink. In this sense, Perthro could mean potential and the vessel that carries it.

Algiz—Barrier, Hidden Danger

Algiz is the rune of the elk-sedge, a type of grass that grows in swamps and marshes. In the Anglo-Saxon poem the elk-sedge cuts anyone who touches it. This suggests the rune algiz represents something seemingly safe that is actually harmful but also something that can be a barrier, depending on context and use.

S wil

wil —Sun

—Sun

Sowilo is the rune of the sun. In the rune poems, the sun is the light of the world, a source of comfort to travelers and bringer of warmth. Sowilo is a hopeful rune and bringer of good tidings. It represents the power the sun holds in our lives.

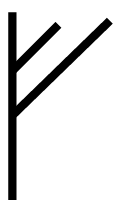

T  waz—Tyr, Justice

waz—Tyr, Justice

Tiwaz is the rune of Tyr, the god of Justice. In the Norwegian and Icelandic poems, he is explicitly named, while in the Anglo-Saxon poem Tyr, named as Tiw, is called the guiding star. Tiwaz represents all of what Tyr is as a source of guidance and inspiration. It also represents justice in all its forms, whether that is achieved through law or other means.

Berkanan—Birch, Hope, Renewal

Berkanan is the rune of the birch, a tree that is noted in the rune poems for its fresh appearance and green leaves. It carries with it renewal and new growth. It represents the potential for new life, new possibilities and new beginnings to spring forth.

Ehwaz—Cooperation, Horse, Movement

Ehwaz is the rune of the horse. Horses were a means of travel, and according to the Anglo-Saxon poem, a source of comfort and joy for their riders. This also suggests Ehwaz is a rune of cooperation, as horse and rider must work together to move ahead.

Mannaz—Community, Humanity

Mannaz is the rune of humanity. In all of the rune poems the related runes describe the greatest joy of all is sharing space and time with other people. Mannaz represents humanity collectively and the shared communities that make us most human.

Laguz—Water

Laguz is the rune of water and the vastness of the ocean. The poems carry connotations of great mystery and the awe-inspiring power of a great unknown. Water also causes change and is itself changeable.

Ingwaz—Fertility, Seed

Ingwaz is the rune of Ing, one of the names of Freyr, who is god of fertility. For this reason, runologists believe the rune represents fertility. It is also a rune of potential and new beginnings.

Othilan—Inheritance, Legacy, Property

Othilan is the rune of heritage, possessions and property. It represents what is passed on from those who come before you and what you leave behind. Othilan can mean the stability these things provide as well as their impact. Which of these potential meanings it holds depends on the context in which it appears or is invoked.

Dagaz—Dawn, Day, Revelations

Dagaz is the rune of day. It carries with it the coming of light, new beginnings, and potential. Dagaz also emphasizes the light day brings. It can be interpreted as new revelations or epiphanies along with the more literal meaning of a new day.

The Younger Futhark

|

Symbol |

Name |

Sound |

Meaning |

|

Fe |

F |

Wealth |

|

Ur |

U |

Iron/Rain |

|

Thurs |

Th |

Giant |

|

Oss |

A |

god |

|

Reid |

R |

Ride |

|

Kaun |

K |

Ulcer, Boil |

|

Hagall |

H |

Hail |

|

Naudr |

N |

Need |

|

Iss |

I |

Ice |

|

Ar |

A |

Plenty |

|

Sol |

S |

Sun |

|

Symbol |

Name |

Sound |

Meaning |

|

Tyr |

T |

Tyr |

|

Bjarkan |

B |

Birch |

|

Madr |

M |

Man/Human |

|

Logr |

L |

Sea |

|

Yr |

R |

Yew |

The Younger Futhark 143

The meanings of the Younger Futhark are known thanks to the surviving Norwegian and Iceland rune poems. Though they provide direct, clear meanings for what each rune likely meant, each poem offers a different perspective on these meanings. The meanings are also not as straightforward because both poems, particularly the Norwegian one, freely use kennings to convey meaning, suggesting there were additional layers or implications those composing the poem would have clearly understood.

Fé—Cattle, Liquid Wealth, Jealousy

In the Younger Futhark, Fe as wealth is treated in a very cautious light. In the Younger Futhark wealth is a creator of discord and potentially a source of comfort or security. If Fe emerges or is used, be careful with the context, as there’s more than meets the eye with this rune.

Ur—Iron, Rain

Here Ur, as rain or iron, has a very different meaning from the Elder and Anglo-Saxon Futharks. It is called rain in the Icelandic poem, iron in the Norwegian poem, and in both places is treated with caution. Rain at the wrong time can ruin a harvest, and bad iron can bring death to the user. Ur must be used with respect for its double-edged power.

Thurs—Giants, Overwhelming Power

Like the Elder Futhark, Thurs is the rune of the giant. In the Younger Futhark, giants are seen as dangerous and harmful to people. They are also beings of great power with great means to cause harm. Thurs must be treated with the same care as Thurisaz, whether it appears in a reading or is used in a working.

Oss—Estuary, Odin, Openings

Oss, like Ur, has two different meanings in the Younger Futhark. In the Norwegian poem, Oss is the rune of the estuary, a rivermouth that opens into the sea. In the Icelandic poem, it is associated with the god Odin. Between the two, it represents a place where things flow out into the world or Odin as a bringer of knowledge.

Reid—Travel

Reid is the rune of travel and journeying. As the rune of riding, it also carries an extra emphasis of a speedy journey (at least in the Icelandic poem), and calls attention to the burden it places on the steed. Reid can represent travel in every sense, including the abstract.

Kaun—Disease, Harm, the Ulcer

In the Younger Futhark, Kaun is the rune of the ulcer. It is clearly described as a symptom of worse diseases that bring a bitter end for its victim. It is a warning sign, an indication of a source of harm, or an omen of malice.

Hagall—Destruction, Hail, New Possibility

Hagall is the rune of hail and new potential. Both poems call it the cold grain, showing that while hailstones can bring destruction, they also carry within them the seed of new growth. This makes Hagall a rune of ending and beginning.

Naudr—Binding, Frustration, Obstacles

In the Younger Futhark, Naudr is the rune of binding, restriction, and the grief they bring. It represents restraining obstacles, whether imposed by yourself or others, signaling the existence of chains in need of breaking or invoking their essence.

Iss—Ice, Order, Stasis

Iss, like in the Elder Futhark, is the rune of ice. It represents both the steady, grinding change of glaciers and ice’s ability to lock things in place. It also, as is suggested in both poems, represents the potential opportunities that ice can open up, similar to how a frozen lake or river can provide a new road for travelers.

Ar—Abundance, Generosity

Ar, as the rune of plenty, stands in stark contrast to Fe. Where Fe in the Younger Futhark warns of the strife caused by wealth. Ar is more positive. What sets Ar apart is the emphasis on sharing abundance generously with others. Ar invokes and represents plenty while also reminding us that bounty should be shared, not hoarded.

Sol is the rune of the sun. In the Younger Futhark is special emphasis on its role as a bringer of light and warmth, suggesting it is a rune full of potential and transformative power.

Týr—Justice, Tyr

Tyr is the rune of the god bearing the same name. In the Younger Futhark, this rune is unquestionably his, making it associated with all he represents. This rune suggests the presence of the One-Handed God in what is at work and can bring all forms of justice.

Bjarkan—Birch, Renewal

Bjarkan is the rune of the birch in the Younger Futhark. In these poems, the birch’s greenery and freshness is emphasized, showing it is a rune of new possibility and growth.

Madr—Community, Humanity

Madr is the Younger Futhark rune of humanity. In the poems, it describes the greatest joy comes from the company of others. Humanity, under Madr, is realized through community with others. Its appearance or invocation carries the same power.

Logr—Water

Logr is the Younger Futhark rune of water. In the poems, water’s movements are the focus, whether it is in the shape of a stream, waterfall, or geyser. This shows water as a changeable, dynamic force. Logr carries the same power in readings and invocation.

Yr—Bow, Endurance, Yew

Yr is the Younger Futhark rune of the yew tree. In the Norwegian poem, Yew is the greenest of trees in the depths of winter, showing its endurance. The Icelandic poem speaks of using yew for making bows. This shows Yr is enduring, flexible, and potent, representing many possibilities when invoked or appearing in a reading.

The Anglo-Saxon Futhorc

|

Symbol |

Name |

Sound |

Meaning |

|

feoh |

f |

Wealth |

|

|

u |

Aurochs |

|

thorn |

th |

Thorn |

|

|

o |

god |

|

r |

r |

Ride |

|

c |

c |

Torch |

|

Symbol |

Name |

Sound |

Meaning |

|

gyfu |

g |

Gift |

|

|

|

Mirth |

|

hægl |

h |

Hail |

|

n |

n |

Need |

|

|

i |

Ice |

|

g |

j |

Year, harvest |

|

|

eo |

Yew |

|

peord |

p |

Vessel |

|

eolh |

x |

Hidden danger, barrier |

|

sigel |

s |

Sun |

|

t |

t |

Glory |

|

beorc |

b |

Birch |

|

eh |

e |

Horse |

|

mann |

m |

Man |

|

lagu |

l |

Water |

|

Ing |

|

Ing (a hero) |

|

|

œ |

Ethel (estate) |

|

dæg |

d |

Day |

|

|

a |

Oak |

|

æsc |

æ |

Ash-tree |

|

|

y |

Bow |

|

|

ia, io |

Eel |

|

|

ea |

Grave |

The Anglo-Saxon Futhorc 144

The names and meanings of the Anglo-Saxon Futhorc come from a single surviving poem. The Anglo-Saxon Futhorc poem is more detailed in descriptions of the runes. It also shows much more explicit Christian influences. Even so, the similarities between what the Anglo-Saxon runes represent and those in the Younger Futhark suggest their meanings are based on pre-Christian ideas.

Feoh—Cattle, Wealth

Feoh, the Anglo-Saxon Futhark rune for wealth, is a straightforward representation of material, liquid wealth. The rune poem urges the reader to be generous with their wealth, giving it freely to others. Feoh carries the same power when read or invoked.

Ur—Auroch, Endurance and Strength

Ur, like in the Elder Futhark, is the rune of the auroch. It is described as fierce and powerful, showing great strength and endurance. Ur carries the same power and meaning, showing the strength of steady labor when read and invoked.

Thorn—Thorn, Potential Danger

Thorn is the rune of the thorn in the Anglo-Saxon Futhark. Thorn is said to be very sharp, harmful, and dangerous to others because of this. In this understanding, Thorn has a clear sense of harm attached to it, suggesting this rune should be seen as a warning of potential harm.

Os—Mouth, Speech

Os is the rune of the mouth and speech. In the Anglo-Saxon poem, it is a source of wisdom, comfort, and joy for all. This shows Os has the power to sway others and cause change or harm, as all speech and words do. It shows the need of words when read or embody their power when invoked.

R d—Riding,Travel

d—Riding,Travel

Rad, like Raido, is the rune of travel and riding. Here it also carries the message that journeys may seem easy at first but have their own challenges. In a reading, Rad shows travel of some sort lies ahead. When invoked, it can carry the wanderer forward.

C n—Fire,Torch

n—Fire,Torch

Cen is the rune of the torch. It represents light and flame harnessed to improve people’s lives. It is more controlled than raw fire but still carries the potential for destruction. The same is true when Cen is read or invoked.

Gyfu—Generosity, Gifts

Gyfu is the rune of the gift and generosity. In the Anglo-Saxon Futhorc, giving to others and sharing your bounty are praised. Giving in turn requires gifts in exchange, showing the pattern of a gift for a gift. When invoked, Gyfu calls up the wisdom of exchange; when read, it shows exchange may be necessary to reach the desired result.

Wynn—Bliss, Joy

Wynn is the rune of bliss. It is a positive rune that defines what is necessary to have joy. The poem says eliminating suffering and creating prosperity are necessary for creating the ideal conditions for bliss. When read or invoked, Wynn could refer to the coming of such circumstances, or the need to create them, and it brings the power to do so.

Hægl—Destruction, Hail, Renewal

Haegl is the rune of hail. In the Anglo-Saxon Futhorc, it is referred to as a grain along with vivid descriptions of how it whirls around violently in the sky. In reading and invocation, it carries the double meaning of the destruction hail can bring along with the potential for new growth.

Nyd—Adversity, Need

Nyd is the rune of need and adversity. Like in the Younger Futhark, it is clearly seen as an obstacle to a better life. However, in contrast to the Younger Futhark, it also suggests such adversity makes a person better in the long run. When invoked or read, Nyd warns of such difficulties while reminding us that they are often chances for us to grow.

Is—Cold, Frost, Ice

Is is the rune of Ice. In the Anglo-Saxon Futhorc, most of the emphasis is on cold and its fair appearance. Like Isa, Is carries with it all of what ice means while also showing the cold that brings stillness as the core of its essence. When read or invoked, Is reminds us of ice’s static power and the creeping cold that brings it.

Ger—Harvest, the Year

Ger is the rune of the year and the harvest. It represents the abundance and prosperity that comes from a year’s labors. Suggesting Christian influences, it also emphasizes the role of God in providing this. The implication is that fate has a very deep impact on our work through the year, and we should be mindful of it when Ger is read or invoked.

Eoh—Center, Stability, Yew

Eoh is the rune of the yew tree. In the Anglo-Saxon Futhorc, the main focus is on how strongly it holds in the earth and improves the land where it stands. When read or invoked, Eoh shows the power of a strong center that can enrich all around it.

Peorth—Vessel

Peorth is vague in its meaning, though based on the poem it appears to represent some sort of vessel that holds food or drink in a hall. Based on what is known (and keeping in mind the scholars’ debate on this rune’s meaning), Peorth carries the power of both great potential and a container for holding it when read or invoked.

Eolh—Barrier, Elk Sedge, Hidden Danger

Eolh is the rune of the elk-sedge, a type of grass found in marshlands. In the Anglo-Saxon Futhorc, it is clearly depicted as potentially harmful in spite of its innocent appearance. When read, Eolh offers a warning; when invoked, it can be used to ward off danger with hidden defenses.

Sigel—Guidance, Sun

Sigel is the rune of the sun. It is shown as a source of light, joy, and hope for those journeying on the sea. In the Anglo-Saxon Futhorc, Sigel is both the sun’s power and a source of guidance when read or invoked.

Tiw—The North Star

Unlike in the other futharks, Tiw is not associated with Tyr in the Anglo-Saxon Futhorc. It is instead described as a source of guidance that lives in the sky, a fixed point of reference, and useful to those who lead. In this way, Tiw is a point of reference, either literal or abstract, when read or invoked.

Beorc—Beginnings, Birch, Vitality

Beorc is the rune of the birch. In the Anglo-Saxon Futhorc, it refers to birch’s beauty and vitality. Beorc represents such potential, growth, and new beginnings when it appears in a reading.

Eh—Horse, Partnership

Eh is the rune of the horse. It is described here as a joy to riders and a source of comfort for travelers. It is more than just a means for journeying, suggesting one should heed what helps you move through life and the world. These meanings are present in Eh when it is invoked or read.

Mann—Humanity

Mann is the rune of humanity. Like in the other futharks, the emphasis here is how we are at our most human when we are participating in a healthy, supportive, and nurturing community. When read, it suggests all things tied to humanity and community. When invoked, it can bring out what makes these possible.

Lagu—Ocean, Water

Lagu is the rune of water, with emphasis on the ocean. In the Anglo-

Saxon Futhorc, Lagu carries more potential of danger, fear, and uncertainty. If Lagu is invoked or read, it has all of the potential, uncertainty, and risk that comes with the vast power of the ocean depths

Ing—The Hero

Ing is the rune of a great hero. In the Anglo-Saxon Futhorc, it is associated with a person who came to the East-Danes before departing again by sea. Ing, when read, may suggest the coming of times that make heroes or be invoked to bring these qualities forward.

Edel—Estate, Inheritance, Legacy

Edel is the rune of the estate and inheritance. It is the fruits of your forebears’ labor as well as what you leave behind. Edel is property and the process through which it is accumulated, passed on and influences people’s lives. If it is invoked or read, it reminds us of what came before and what comes from our actions.

Dæg—Beginnings, Dawn, Day

Daeg is the rune of day. In the Anglo-Saxon Futhorc, it focuses on hope and new possibilities. Daeg can be invoked to bring forth this power and, when read, suggests a new beginning is coming.

Ac—Oak, Stability, Support, Sustenance

Ac is the rune of the oak tree. The poem discusses how oaks provide food for pigs, shelter, and are strong enough to withstand the fury of sea storms. When read, it could mean there is a new source of support coming or that such strength will be needed. When invoked, the oak’s power is called upon.

Aesc—Ash, Endurance

Aesc is the rune of the ash tree. The ash tree is described as tall, precious to humans, a valuable source of wood, and very tough. Aesc represents endurance and toughness when read or invoked, giving strength or suggesting endurance will be needed soon.

Yr—Bow, Tools

Yr is the rune of the bow. It is described as a source of joy and honor while also being useful equipment on a journey. This is likely because in ancient times bows were used to hunt for food. Yr represents reliable instruments, both in needing and having them, when read, and when invoked, what such tools give to their user.

Iar is the rune of the eel. In the poem, the eel is described as a river dweller that survives by capturing land-based prey. In readings, Iar can suggest a need to leave your comfort zone to get what you need to survive or thrive. When invoked, it can also help give the means to reach beyond your limits and press into unfamiliar territory.

Ear—Death, Endings, Grave

Ear is the rune of the grave. In the poem, the grave is a thing most dreaded, as it is the place of the greatest ending. It also is the home of the dead. These aspects make it a very potent rune. When read, it suggests a powerful, earth-shattering ending is coming, or to heed the dead’s wisdom; when invoked, it can call such power into the world.

Symbols of Power

The runes represent elements of the mentality of the Norse peoples. They provide insights into what they held dear, how they viewed the world and what was important. They also, for the modern practitioner, provide useful tools for art and mystical purposes. The magic of runes is the magic of words, ideas and concepts given form. They offer a way for understanding these deeper concepts, how they are shaped, and what they mean.

The next exercise is meant to help you internalize their meaning, wrestle with it, and understand your own perceptions of the concepts each rune represents. As written, the following exercise is meant to be done with one rune at a time. That doesn’t mean you can’t do it more than once, and you may feel called to do so. Whatever insights you gain from this exercise should be supplemented with study of the runes based on credible, academic sources.

exercise

This exercise is for getting a deeper understanding of each rune, their meanings, and their applications.

Begin with three breath cycles to calm the body.

After finishing your three breaths, do the Calming the Sea and Sky exercise. When the waters are calm and the sky is clear, you may proceed with the next step.

Close your eyes and draw the rune in your mind. When it is completed, do one breath cycle. As you breathe, feel the energy of the breath enter the rune. Do not force any particular form for how this manifests in the rune; let the rune respond in whatever way feels right.

Begin a second breath cycle. With this breath cycle, let your mind be filled with whatever words, images, sounds or feelings you most associate with the rune. Let whatever emerges be what comes most naturally and easily, rather than fitting any preconceived image of what should be. The results may be surprising to you.

Breathe in to a count of nine while keeping whatever emerged during the previous step in your mind. As you breathe out say the rune’s name to a count of nine. As you do so, feel whatever you have associated with that rune flow out with your speech.

Begin a third breath cycle. With this cycle, like the first breath cycle in this exercise, feel the energy of your breath fill the rune again.

Breathe in to a count of nine, then, as you breathe out, say the rune’s name to a count of nine. As you do this, visualize the rune leaving your mind and flowing out from you with your breath. Spend some time sitting with the feelings, images, sounds, and other associations the rune brought up for you.

137. Havamal 138-140, Poetic Edda

138. Michael P. Barnes, Runes: A Handbook, Boydell Press (Woodbridge: 2012), 4–5, 9–10

139. Tacitus, Germania 10; Vita Ansgari, 26–30.

140. Sigrdrifumal 5-10, Poetic Edda; Sturluson, Snorri, Bernard Scudder, and Svanhildur Óskarsdóttir. Egils Saga. Penguin Books, (New York: 2004), Chapter 44; Terje Spurkland, trans. by Betsy van der Hoek, Norwegian Runes and Runic Inscriptions, Boydell Press (Woodbridge: 2005), 11–12.

141. Meanings for the Elder Futhark are from Barnes, 27.

142. Barnes, 157.

143. All Younger Futhark rune meanings are taken from Runic and Heroic Poems of the Old Teutonic Peoples, edited by Bruce Dickens, Cambridge University Press (Cambridge: 1915), 24-33

144. All Anglo-Saxon Futhark rune meanings are taken from the translation by R.I. Page, An Introduction to English Runes, Boydell Press (Woodbridge: 1999), 65-76

d

d n

n

d

d