1

The Current Situation

on the Philosophical Front

I. SO MANY MOTLEY SOLDIERS ON ONE FRONT

Philosophy as partisanship. Philosophy as concentration of antagonism, in terms of worldview. Philosophy thoroughly summoned by history. The servant not of the sciences but of weaponry. Not the reign of the eternal, much less of wisdom, but the trenchant figure of the actual, of the divided, of class. Not heaven and air, the place of contemplative transparency. Not at all the nocturnal waters of reconciliation. But the resilient earth of production, the weight of interestedness, the fire of the historical ordeal.

Here we are going to place a few names, three notable names on the whole apparent surface: Lacan, Deleuze and Althusser. Does this not say it all? No, because our philosophical time, since the revolt spread, no longer finds an emblem in a name. Every list of notables is foreclosed. We will explain why these names are at best masking and misleading the philosophical novelty that is at stake. What they tell us about the forces of the real is foreign to these names themselves.

There is only one great philosopher of our time: Mao Zedong. And this is not a name, nor even a body of work, but time itself, which essentially has the current form of war: revolution and counter-revolution. There is nothing else to say, philosophically speaking, than the anteriority of this division with regard to any philosophy. Which is why what matters is the line drawn at the front.

When our Chinese comrades talk about ‘struggles of principle’ that take place on the ‘philosophical front’, they have in mind the stages of revolutionary politics. Philosophical attacks and counterattacks accompany the historical periodization. The philosophical preparation of two camps aims at drawing up a balance sheet of one stage and concentrating the forces for the new stage that is just opening up. Philosophy possesses no more permanence than does the revolution. It enters the scene at the great turning points of history.

For three or four years now, philosophy enters the scene by way of a practical question that occupies all philosophers, whether avowedly or not: what has been the significance of May 1968? We will show that everything that is said about Power and Desire, about the Master and the Rebel, about the Paranoiac and the Schizophrenic, about the One and the Multiple, takes a stance and resonates with regard to this question – what has happened in May 1968? What has happened to us? And, within this national variant, the universality of this particularity, still only one question: what happened in the USSR after the October Revolution? What happened during the Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution in China? What happened to Marxism? There lies the front line where everyone battles, rallies, mobilizes or wavers.

There are so many ‘philosophers’ today! You have the dealers in nihilism, the inflationists of petty and personal misery, the flute-players of capital and nomadic subversion, the Nietzschean undermen and the proclaimers of Sex. You have the anthill of laborious epistemologists. In the heavens, the procession of Angels, Virtues, Thrones, Dominations and Seraphim; on earth, the resignation to the Master and the Law. The exegetes of Discourses, and the eulogists of textuality. Those who, in Le Nouvel Observateur, solemnly declare that God is not as dead as He looks. Those who, in stupor at the exit from the latest Seminar, tie together the obscure threads of the Borromean knot. Those who with their own eyes have seen that the seventy-fourth burial of Marx, or of Lenin, was undeniably the good one. Those who hate: thought, Marxism and the proletariat (but do they even possess the force of hatred?). Those who love: their ego, their sex and their voice (but do they even possess the force of love?). And the apostles of bad faith: those who amass their clientele by baptizing ‘Marxist’ the antiquated bourgeois conclusions about Stalin or about the Lysenko affair. Those who offer the friendly advice to the PCF that its window dressers better keep the dictatorship of the proletariat in the jars on the shelves, just in case. Those who rely upon the forgotten sciences, the crushed revolts, the falsified texts, in order to represent the tenor voice in the operetta chorus in honour of ‘Eurocommunism’.

But all these speculative fortune-tellers, charlatans or honest retirees meet in the place assigned to them by history: where do we stand today with regard to the revolution? And even those who, together with their soul, sell to the bourgeoisie the pompous formulae of vulgar defeatism, must be seen as standing on the front line, such as it seems to become fixed between two storms.

Marxists have always said that the decomposition of a revolutionary impulse causes the two faces of selfish reinvestment to flourish among the exalted petty-bourgeois who have fallen from on high: pornography and mysticism. Today we can see both: Desire and the Angel. However, history is never a simple story of forms, it deforms and splits even that which it repeats.

II. POINT OF DEPARTURE: A SILENT THUNDER

May 1968, and even 1969, 1970, 1971: the masses front stage, the omnipresent Maoist ideology, albeit with Linbiaoist inflections – this was the silence of the garrulous philosopher, of separated philosophy. There is nothing more surprising than to compare this strong and violent uprising, this real and simple philosophy, which is everywhere at work in the substance of the movement in revolt, that is, the retreat and vacuity of academic discourse, with the logorrhea of the confessional in which everyone today spills their misery and their apocalypse. What then has happened?

In the end, the years 1968–1971 lent themselves only to the most real philosophy, the one that forms a single body with the practical questions of the revolution. In the heat of the moment people worked on ‘One divides into two’ in order to analyze the revolts; they called upon the class origin of ideas to bring down the reign of the mandarins. ‘Antagonism’ and ‘non-antagonism’ were distinguished in order to push to the end the workers’ struggle against the PCF and against the unions. ‘Identity’ and ‘difference’ referred back immediately to the place of the organized Maoists in the movement and to the inventive force of the popular masses.

The historical breadth of the phenomena simplified the task of formal thought, barred speculation, and by force led back to the practice of masses and classes. The idealist deviations, which did not fail to appear, especially among the ‘Maos’, remained powerfully subservient to the immediate density of their contents.

Mao’s philosophical writings themselves were inexhaustible, since they were supported by the inexhaustible force and capacity for rupture of the real movement. All the rest disappeared into futility. Roused out of itself through the relaying of the student revolt by the working masses, the so-called revolutionary intelligentsia of the petty bourgeoisie continued to feel exalted, on top of history. With enthusiasm it gave up its ordinary sophistication, because it imagined itself at the heart of the storm, with nothing more to do than to fuse its ideological and moral virulence with the harsh battalions of the factory revolt, in order to reach its victory.

III. THE REVERSALS OF 1972

This great and violent era sees its cycle come to an end around 1972. The mass of petty-bourgeois intellectuals understood little by little that, appearances notwithstanding, it was not the paladin of history. The fury of its ideological tumult, its exalted passion for ‘struggles’, its devastating impatience, if they were not organically linked to the people’s revolutionary politics – at the heart of which stands the proletariat as the only antagonistic class of the bourgeoisie, and its avant-garde as the leading nucleus of the people in their entirety – became inverted into their opposite under the recovered weight of the fundamental clash, that of classes and their programmatic interests. The discovery of the masses was an anti-revisionist impact force of the first order; and the discovery of Maoism, a cultural revolution without precedent. But Maoism is not solely the apologia of revolt, it is the Marxism of our time, it is the thought and practice of proletarian revolution in the space opened up, on a worldwide scale, by the Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution. Maoism, too, puts the petty-bourgeois intellectuals in their place, just as starting in January 1967 the Chinese revolutionary proletariat, taking control of the storm, gave both its strength and its limitation to the spirit of revolt among the young red guards.

If one did not hold onto this historical and theoretical truth and translate it into the facts – as is the path of Marxism-Leninism-Maoism – what did one see? The ideologico-moral tumult turned into hollow terrorism, or flipped over into shapeless decadence; the passion for ‘struggles’ washed out into cautious conformism behind the bourgeois unions; the impatience slipped into defeatism.

These reversals were accelerated by the fact that the bourgeois counter-offensive, via the Union of the Left and the Programme Commun,1 in the end left our ideologues completely disarmed. The adversaries, who up to this point had been on the defensive in the face of the revolts and the ideological rapid fire, finally started talking politics (that is, programmes and power), which is something of which the petty-bourgeois would-be revolutionaries are congenitally unable, being only the bearers of a principled, and thus abstract, vision of politics. For them, the strong antagonistic patience of the programme of the revolution is nothing more than popular materialism. They dream of a formal antagonism, of a world broken in two, with no sword other than ideology. They love revolt, proclaimed in its universality, but they are secondary in terms of politics, which is the real transformation of the world in its historical particularity.

The programmatic return to the proletariat and to the people, inevitable to keep steady in the face of the two bourgeoisies – which after the storm, and then in the form of the economic crisis, reconstituted their political space, their plans and their combats – was for the ‘leftists’ an unbearable test. They had believed in the blinding coincidence of their newfound morality and the historical aspirations of the people. Now they discovered that once more, in order to be the fortune-tellers of the revolution, they had to submit themselves to the internal process by which the proletariat appropriates its new historical dimension, formulates its programme, and strengthens the nuclei of its future party. To suppress oneself as a bourgeois intellectual was not some parousia but a labour.

The majority, it must be said, threw in the towel and returned to their sheep. Which is when they discovered the avenging virtues of philosophy.

IV. REVANCHISTS OF THE IDEA

Chased away from the front stage, our ‘Maos’ from the night before, and most notably their petty chiefs now gone astray, swore to take their revenge in philosophy for the trick that history had played on them. Since no one still wanted them to take the leading role, they were going to show that the play was bad and its principal actor (the proletariat) would henceforth be responsible for a vile fiasco.

Since it was established that, not being a true political class, a state-bound class, the petty-bourgeois intelligentsia had no chance of ever exerting power, well then, they were going to show that Power is Evil. In this way they would remain the heroes of the whole affair, ideally changing the defeat of their vain ambition into the noble disapproval of its stakes.

Since they had been carried away by the ideological exaltation over the revolt of the masses, but now it seemed that without class structure, or without the antagonistic proletarian framework, the revolt does not carry the revolutionary politics for very long, they were going to say: the Masses are good, but the Proletariat is bad. The revolt is good, but politics is bad. The spokesperson is good, but the militant is scary.

Since Marxism was the means for the proletariat to exert its theoretical hegemony in the camp of the revolution, they would not hesitate to reveal a great secret: Marxism is bad.

The ‘philosophers’ of the moment, with their brilliant paraphernalia, have no other function than to organize the following three theses:

a)the masses (revolts) are good;

b)the proletariat (Marxism) is bad;

c)power (the State, in whatever form) is Evil.

All these discourses filter their dismal balance sheet of May ’68 and its aftermath through the political matrix of mass/class/State, for which they propose singular universalizations. The political essence of these ‘philosophies’ is captured in the following principle, a principle of bitter resentment against the entire history of the twentieth century: ‘In order for the revolt of the masses against the State to be good, it is necessary to reject the class direction of the proletariat, to stamp out Marxism, to hate the very idea of the class party.’

Everywhere to substitute the couple masses/State for the class struggle (that is, everywhere to substitute ideology for politics): that is all there is to it. And this is because the petty-bourgeois intelligentsia can parade around in the ineffective revolt, but it is in agony in the prolonged proletarian class struggle.

It does not like the dictatorship of the proletariat, it does not seek the dictatorship of the proletariat, as long as imperialism nourishes it to satisfaction. Nothing else exists in politics? Then, at its lowest, it will say: long live the Nothing! In the vicinity of the retreat after 1972 roams the nihilist sarcasm, the profound apoliticism, the pre-fascist aestheticism of these petty old men of history.

So that is the soil where our ‘philosophies’ grow. We will see through all these ‘balance sheets’ of May 1968, of October 1917, even if instead of the Masses, we obtain: the body, or desire, or the multiple. Instead of Class and Marxism: Discourse, or the Signifier, or the Code. Instead of the State: Power, or the Law, or the One.

Indeed, it is from the point of view of the reconstitution of their vacillating identity and from the restoration of their social practices that our intellectuals transmit their memory and their vengeful verdict. Everyone, including the Maoists, is after all called upon today, after the Cultural Revolution and May ’68, to take a stance, to discern the new with regard to the meaning of politics in its complex articulation, its constitutive trilogy: mass movement, class perspective, and State. Such is clearly the question of any possible philosophy today, wherein we can read the primacy of politics (of antagonism) in its actuality. The difference is that the Maoists practice this question under the sign of the revolutionary politics of the people, the core of which is the antagonism bourgeoisie/proletariat. And our philosophers do so in the denial of antagonism, through their newly shared disengagement and their vindicated ignorance of the popular political realities. At a time when what counts is the question of the programme of the revolution, the petty-bourgeois intelligentsia finds itself largely out of place, cut off from politics, bound to a clear class choice from which its entire being desperately turns it away. And yet, politics is what makes it talk, it is the balance sheet of the storm that has it all worked up. So there it is forced to manipulate the poor, miserable content of its immediate social life (I read a little, I talk, I teach, I publish, I make love), to stage it in the place and stead of that which makes up the true backbone of their own history. The impoverishment, the abstract sophistication of the contents, the exaltation of the most individualistic and rarefied ‘lived’ experience: all this is what refracts, in the recuperation of social uses, the muffled thunder of the shaking up of history, whose features the petty-bourgeois intelligentsia no longer recognizes, even if it continues to carry along the question they pose.

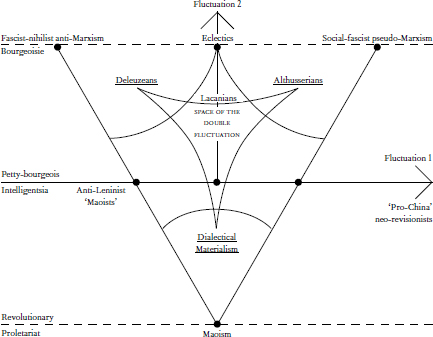

We could propose a figure for the thread of this progressive misrecognition, in which the following contradiction can be read:

a)What forces the petty-bourgeois intelligentsia to think is the massive nature of the historical interpellation since 1968, the core of which is politics, that is, the system mass/class/State in the actuality of antagonisms.

b)Thrown back upon the periphery of the antagonism and dominated by the idealist restoration, the petty-bourgeois intelligentsia progressively misrecognizes that which constrains it and disguises it in generalizations whose referent is nothing else, in the final instance, than its immediate social practice (hence the Body, Writing, Enjoyment, etc.).

This gives us, for example, with variable sedimentations and measures of transparency:

This is the trilogy (the real movement, the organization, the dictatorship) with its metamorphoses, but taking a resentful stance on May ’68, on the revolutions of the twentieth century, and bracing itself for the categorical refusal of the only confirmed, practicable revolutionary road, which can be read here and now: that of the dictatorship of the proletariat and of Maoism.

As for us, placed up close to their source, practicing the politics that they deny, which is the only real referent of philosophy, including theirs, we will always be able to translate statements such as the following into their historical actuality: ‘Discourse is that which disposes the body as the effect of a power.’ Let us read: for us, historically responsible (or irresponsible) for vacillating formations, we refuse that the proletariat (Marxism) directs the processes (the movement) in their revolutionary relation to the State (the dictatorship of the proletariat). And, if we are told: ‘The desiring multiplicity is inverted by the coding into the axiomatic unity of capital ’, we will read in it the same denial. Or again: ‘The plebs is subordinated by Marxism to the Gulag’, this is once again: mass, class, State, in the stubborn denial of their political articulation.

To break up the ineluctable proletarian link: leadership, organization, Marxism, dictatorship. To leave out in the open the atemporal masses: revolt, spontaneity, utopianism, democracy. Under the pretence of attacking its despotism, to deploy the gigantic omnipresence of the State under the metaphysical banner of the concept of ‘power’, alibi of all renunciations, of all cowardice: we are being told nothing else. Nothing, nihil. At the end of this nothing, inevitably, we find fascist violence. This is what the hatred of the proletariat, combined with the abstract cult of the ‘masses’ and the aesthetic despair, is preparing public opinion for.

V. THE OWLS OF THE REVISIONIST NIGHT

Then come the counterfeiters, the company of prebendaries of false Marxism. Annulled by Maoism, nihilism puts them back in the saddle. This is because Althusser and company are more radically nihilist in that, for them, quite plainly nothing happened in May ’68. It is not a question of a negative balance sheet, but of denying the need for a balance sheet to begin with. Revolts? Masses? The people’s revolutionary politics? Where? You have been dreaming! ‘Scientific’ Marxism, that monument sheltered from the storm, offers you, without counterpart, the academic serenity of the conservatories. It allows you, with no attributes other than those of some handsomely remunerated doctors in philosophy, to pronounce yourself about everything and to make heard, albeit in the register of the official oppositions, the great voice of the Party and of the Proletariat. It allows you to scold the petty anti-Marxist nihilists and to envisage History from the lofty heights of the great nihilism, that of the false Marxism, that of the card-carrying professors.

For the moment, politics is the occupation of Marchais and Séguy, Mitterrand and Maire.2 Let them go where they want, provided that they beware of what they say. Our safekeeping mission is that of concepts: the Programme Commun must be able to coexist with the regular allegiance to ossified Leninism.

Scholastic owls of the night of the PCF, the Althusserians are more dangerous than they seem. To pretend that there is any sense whatsoever, today, in continuing the battle for the Marxist and ‘proletarian’ purity of the PCF is to justify, even without wanting to, the worst: the politics of the bourgeois State in the name of the proletariat, the forced indoctrination of class politics, the anti-popular terrorism in the name of Marxism. Yes, when to the Masses of nihilism, to the pure multiple of desire, the revisionist philosophers object by invoking their fake conceptual proletariat, their oppositional allegiance to the One of the PCF, because then what they deny is at once the real proletariat, its work on itself, its revolted insurrection in the element of Maoist politics, they open the way to a ‘red’ despotism, under the pretence of white fascism. We say: the Althusserian company of concepts, of science above classes, does not organize in any way the ‘left’ of the PCF. Indeed, there is no worse bourgeoisie than the new bourgeoisie, the one who only speaks of the proletariat and of the dictatorship of the proletariat.

VI. THE SCEPTIC

Standing apart, tall dinosaur with his old rational step, idealist dialectician, true successor of the one and only Mallarmé, of the only productive Hegelian of our dominant national tradition of thought, drowned in the coquetry of his opacities, prey to the frenetic rhythm of sofas and doctors where plenty of repented enragés meant to use psychoanalysis to silence the commotion of politics: Lacan, bourgeois sceptic, also spreads the dangerous conviction – that there is nothing new under the sun.

What saves him, however, is the fact that he never pretends to draw any politics whatsoever from this, except to say that, after all, it is only ever a question of being subjected to the least bad master possible.

Those who extract or bet on a form of politics for him– that is to say, those who fuse with or split off from Lacanianism in the wake of their assessment of ’68 – find no other ground to stand on, no other determination to bring to bear, except their apparent enemies, the nihilists and the naturalists of desiring multiplicity. Same refrain of the pure but unlikely Revolt, of the sinister proletariat and the unavoidable Master. Same trilogy. Same despair to scrutinize the points of desire where the enjoyment of Power becomes anchored. Same blindness.

About Lacan himself, one will say that his most extreme misfortune is to validate, by way of his atemporal scepticism, the counter-revolutionary continuum in which the Union of the Left prospers: the species of Lacano-Althusserians, alas, has not yet died out.

VII. THE PRINCIPLE OF DOUBLE FLUCTUATION

So goes the philosophy of those scalded by May ’68, the weapon of war against the truth of May ’68, against its popular and worker’s truth, the truth of its force and of the prolonged Maoist work of its force: fluctuating and fascinated now by nihilistic fascism and now by ‘scientific’ social-fascism.

In the ‘crisis’ of philosophy, for those who confess it, we will see a single fallacious problem, fabricated in the movement of historical and political foundering after 1972: how to give life, in the wedging of fascism and social-fascism, of Deleuzian banditry and Althusserian science, to the tri-logical principle that all the exhausted old combatants seek to sell to the highest bourgeois bidder? For the masses to be purged of the State, we must hate the proletariat. For sex to be without Law, we must make a hole in the text. For the multiple desire to be without One, we must recuse reason. For the body to be detached from Power, we must fissure discourse. And so on.

Here we are no longer talking about the fortune-tellers and the professors, the charlatans and the spokespersons but about those – the vast majority – who inherit this falsified balance sheet, its immense weariness, and carry on their backs the infamous problem that is handed down to them: the problem of renegacy. Those who read Deleuze, and Lacan, and Foucault, and Althusser, and all the epigones, and think: where do we stand? What are people telling us here?

To this question we must again and always answer: history, class struggle, politics.

It is a stupid illusion to imagine that the philosophical conjuncture could be independent not only of the general set of phenomena of the class struggle but also of politics, of what gives structure at a given moment to the political scene in a dominant fashion. Today, what apparently predominates this scene is the rivalry of two bourgeois projects: that of the classical monopoly bourgeoisie, whose political expression, itself complex, is the coalition of ‘advanced liberalism’ of Giscard and Gaullism; and that of the new state bureaucratic bourgeoisie, which finds its parliamentary form in the Union of the Left and its syndicalist support system. With regard to this rivalry, the popular working movement is in search of its political autonomy. The class struggle thus unfolds on two fronts.

To clarify the sense of disarray and complexity in the face of philosophical proliferations, it is thus indispensable to understand that the petty-bourgeois intelligentsia is today historically situated in a force field with three poles, finding itself subservient to what we will call a principle of double fluctuation:

a)First of all, as intermediary social force, the petty-bourgeois intelligentsia oscillates in function of the moment’s relations of force between the proletariat and the bourgeoisie – that is, from the point of view of the conception of the world, between Maoism (the Marxism of our time) and anti-Maoism (whether anti-Marxist or pseudo-Marxist).

b)The petty bourgeoisie is furthermore subject to the attraction and the attempts at hegemony of two bourgeois projects. It oscillates between classical reaction and modern revisionism – that is, from the point of view of philosophical expression, between anti-Marxism and pseudo-Marxism.

We cannot therefore offer a linear figure of the system of ideological and philosophical trends that structure at such or such a moment the petty bourgeoisie. It is important to represent it in the space of the class struggle on two fronts, as a kind of triangle that becomes deformed according to two axes of fluctuation whose engine is, on the one hand, the antagonism of bourgeoisie/proletariat, and on the other hand, the rivalry of the old bourgeoisie and the new bourgeoisie. It is with regard to this ‘triangle of forces’, anchored in the historico-political class struggle, that we can map the philosophical reference points of the double fluctuation, and thus draw up the political cartography of philosophy in France.

VIII. A MAP

1) About the place of Deleuzians and Althusserians, as well as of dialectical materialism, we have nothing to add, except that the philosophical space they occupy stands in variable proximities to the pure expression of political interests whose service they guarantee. To grab the ‘horns’ of this fluctuating triangle in space means that there exist, of course, as collective phenomena, fluctuating Deleuzians who are by no means incorrigible fascists; there also surely exist fluctuating Althusserians who are capable of feeling repulsed by the real practical form of social-fascism; and also philosophical partisans of dialectical materialism who are still inconsistent and hesitant with regard to Maoist politics.

2) By ‘anti-Leninist Maoists’ we understand those who, under the pretence of preserving Marxism from revisionism, accuse the Leninist theory of the party and the class essence of Marxism-Leninism-Maoism for the degeneration into social-fascism. In so doing, whether they are council communists or theoreticians of the ‘abolition of wage-labour’, sectarians of the plebs or of popular memory, or apologists of the peasantry as the only true revolutionary class, they objectively tend towards proximity with the Deleuzian ‘massists’ and their anti-militant fury. Their utopias of the countryside – workerist or anti-repressive, depending on the case – are disarming in that they are opposed to the historical task of the moment: the constitution of the proletariat into the political class (which is something altogether different from its existence solely as a social class).

3) By ‘pro-China neo-revisionists’ we understand the ossified Marxist-Leninists, of the Humanité Rouge kind.3 Their philosophical vacuity is, in reality, extreme.

4) The ‘eclectics’ are those who discern full well the common essence of the ‘desiring’ faction and of Althusser: the disavowal of the autonomy of the proletariat and the hatred of Maoist militants. The eclectics validate both the sexo-fascism and the theoreticism. Typical example: Macciocchi or Tel Quel.4

IX. WHAT FOR?

Yes, what good is this cartography for? The fact is that there is fluctuation, that today the hegemonies are broken. The muted and organic rise of workers and the people to the antagonistic struggle on two fronts is reflected, by the petty-bourgeois intelligentsia, in the philosophical need – that is, the need to be done with the bilateral bourgeois subjections, even if this is not yet clear.

What we see today is that around and upon the initiative of the Maoists – or else more sporadically, even blindly and inconsistently – a double rejection of bourgeois impostors is taking shape in the field of philosophy:

•the anarcho-desirers are attacked by a growing fraction of the petty-bourgeois intelligentsia and of the youth who draw up the balance sheet of the disarray, the historical impasse in which these apologists of anything whatsoever have totally led them astray between 1972 and 1975;

•the Althusserians are put into question by the ever more evident incoherence between their apparent formal fidelity to certain principles of Leninism and the flagrant opportunism of their political operations vis-à-vis the PCF.

Our fundamental aim is, in the final instance, that this double critique, combined with the search for a rationality of a new type and with a living thinking of the history of our time, may go forward and break the encirclement attempted by the two bourgeoisies so as to formulate, with Maoism as its axis, its own expression, which is itself the reflection of the historical activity of the proletariat to constitute itself into the political class.

We are strongly convinced that this is an ever-growing aspiration, even if innumerable charlatans try their best to close the gap.

The following studies seek to be at the service of the mobilization for this task, in order to enable the dominant camaraderie of philosophy and of the mass movement, as class confrontations.

The aim is clear, which is why we put forth some provisory markers here and make a general call: may all genuinely revolutionary philosophers arm themselves for the true balance sheet and the antagonistic struggle on two fronts. May they contact us and join us. In this way they will contribute, in the work of preparation for a revolutionary public opinion, to breaking the worst threat to which our people have been exposed: that of a forced recruitment into one or the other of two bourgeois camps. In this way, too, they will play an integral part in the autonomy of the people’s revolutionary politics.