CONNECTING YOUR TALENTS TO INTERESTS

“I hadn’t thought of myself as a creative person because I’ve never been particularly good at art. But now I see there are many ways of being creative and I don’t have to continue in civil engineering just because I’m good at math and science.”

—CIVIL ENGINEER SHIFTING TO LANDSCAPE ARCHITECTURE AS A RESULT OF REASSESSING HER INTEREST-BASED TALENTS

“It’s really difficult determining what other interests would enable me to use my talents differently after working for 35 years in a managerial capacity.”

—EXECUTIVE CONTEMPLATING HIS RETIREMENT OPTIONS AND LOOKING FOR SOMETHING MORE THAN GOLF

“Have fun. Have more fun than any team in the tournament. People perform better when they’re happy.”

—JIM LARRANGAGA, BASKETBALL COACH OF GEORGE MASON UNIVERSITY’S 2006 NCAA CHAMPIONS, AARP MAGAZINE (January/February 2007)

Reassessing Your Talents

Reassessing Your TalentsTwentieth-century intelligence tests created the spurious impression that a number could gauge an individual’s capability. Thanks to the limited dimensions of intelligence measured by all those tests, many of us came to believe that only a small percentage of us were highly intelligent, that quite a few of us were pretty dull, and that most of us fell into a bell-shaped curve of mediocrity.

How intelligent you considered yourself to be, based on this old way of measuring and reporting I.Q., most likely had a huge impact on your sense of self-esteem. On the one hand, if you came away with a score that signified you as having a high I.Q., you may have found yourself proudly parading around as one of the gifted few. If, on the other hand, you were one of the many whose scores indicated mediocre intelligence, you tended to function in ways consistent with the expectations of midrange intelligence. And if your scores fell into the below-average range, you may have been placed in special programs with other “slow learners” or students with “special needs.” Wherever your scores landed in the spectrum, you probably thought that you had been pegged for life as being categorically brilliant, mediocre, or dumb.

A friend recently demonstrated the impact of I.Q. scores on self-image. In an experiment in a graduate psychology course he was teaching at The Johns Hopkins University, he administered an intelligence test to his students and then, unbeknownst to the students, arbitrarily assigned I.Q. scores to their test results. He awarded no score higher than 105, even though these were bright students. In the next class session, he handed out the fake test results and then asked the students to stand in the appropriate corner of the room based on their I.Q. score. Even though he had assigned no score above 105, most of the students went to the corner designated for scores of 130 or above. Had you been in that class, which corner would you have gone to—the high I.Q. corner, or one designated for mediocre scores? The point my friend wanted his students to understand was how strong the impact of an I.Q. score can be on us all. Of course, these students may have ignored the false I.Q. scores because they already knew what their actual scores were and/or went to the corner that matched their perceptions. Whatever their motivations for ignoring the false-score test it brought home in a dramatic way the impact an I.Q. stigma can have on one, especially in the formative years. Understanding this was especially important for these students, since most of them were already teaching or would be in the near future.

If you believe you are highly intelligent, chances are you are going to perform that way. If others believe you are highly intelligent, chances are that they are going to treat you as such. Well-documented research shows that run-of-the-mill students whose teachers believed them to be highly intelligent significantly outperformed similar students who had teachers who believed them to be average students. From countless examples such as these, we have come to realize that our potential cannot be determined by a number. Yet we let numbers supposedly relating to intelligence affect our self-esteem and our performance, even though we all know of individuals who broke through the burden of being branded as “average” or “below average.” Einstein, a name virtually connoting “genius,” was labeled as a dullard by his teachers in his early school years. Although not a genius, perhaps, by Einsteinian measures, Ed, my roommate during my senior year in college, had had his application for admittance to the university turned down because of low SAT scores. Being a very persuasive guy, however, Ed was able to convince university officials to admit him on probationary status. He graduated in business administration with high honors and went on to obtain an MBA and pursue a highly success career in finance.

Recent research in the psychology of human potential is dramatically changing our views about individual capabilities. The emerging view is that everyone is talented, but we are talented in different ways. It follows from this expanded view of human capability that we all should be able to find the unique path in life and work that develops and uses our special endowments. To me, this revisionist view of unique giftedness seems intuitively correct. I’ve seen many examples of the difference in quality of life that we can make by shifting from work for which we are moderately suited to work that is a good match for our talents and interests.

Each of us is a one-of-a-kind creation. Every one of us is a composite of countless varieties of genetic combinations, stretching back into ancestral infinity. So, for instance, once upon a time if you united a Celt with Viking, the result was progeny never before seen on the planet. Then over hundreds of generations, if you mixed the offspring of that union with marauding Mongols and Visigoths, stirred in some Normans, and sent them to America, where they mixed with Germans, Ethiopians, Persians, and Native Americans, you would end up with someone like you and me.

Some of us carry genes from masters at cave-wall painting, and others are genetically descended from experts at slaying mastodons. There has never been another person exactly like you on this planet. So why do so many of us conform to such a few general paths in life, developing similar competencies, acquiring similar bodies of knowledge, and pursuing similar career trajectories? What happened to our instincts for hunting mastodons? Who remembers how to transform a buffalo skin into a colorful garment? Who carries the instinctive ability to design frigates that can overtake and subdue pirate ships?

In spite of our uniqueness, few of us have had the opportunity to develop and apply the gifts arising from our unique heritage over eons of time. Of course, once in a while a Galileo or Mother Teresa or Oprah Winfrey comes along. Most of us, however, allow the world we live in to squeeze us into a limited number of prescribed molds. In school we all had to take the same courses, read the same books, pass the same exams, compete for the same colleges and jobs. We even had to learn to play games the same way—I never saw anyone play football using a tennis ball, or hook the ball through the goal posts with a golf club. Cheerleaders do set routines, and we all cheer in unison at the same things.

Time for the Real You to Stand Up

Time for the Real You to Stand UpOur jobs and the culture of our workplace required that we apply prescribed skill sets and accommodate our personalities to business needs. I’ve counseled many former IBM employees who were never comfortable with the corporate culture of sameness that they felt they were forced to accept. But I’ve also heard the same complaint from clients who worked elsewhere. Just as clients from IBM may have protested their “professional dress code” of blue shirts and dark suits, some of my clients from the U.S. State Department say they never want to see another white shirt or dark suit. Corporate culture determines more than our work wardrobes, however. If you wanted to design cars for a large manufacturer of automobiles, you may have developed your skills in auto design with little regard to what your special gifts might actually have been.

Back in the 1960s, I became a naval officer at a young age. Given the draft, my only choice about serving in the military was which branch of service I wanted to pursue. In my youthful ignorance, I thought the Navy would be better suited to my undergraduate degree in geology. And, besides, I liked the Navy’s uniforms for commissioned officers better. So, to make a long story short, I ended up 10 years later with competencies I would never have dreamed of acquiring—namely, getting men to do things they didn’t particularly want to do, like moving airplanes about an aircraft hangar deck without smashing high-ticket weapons into one another. Little did it matter that my talents ran in a different, more creative bent. Like everyone else, I pretty much did what I needed to do to make it in the world in which I found myself. My unique gifts and talents lay buried beneath the demands of my daily responsibilities and survival. Simply put, I needed to make a living, take care of my family, and find ways of fitting in.

Throughout our early and middle adult years, few of us found time to investigate and explore what our unique gifts even were. Not until we turn fifty-something do most of us have the time and inclination to really define our unique gifts and explore fulfilling ways of applying them. Then, as we begin to enter our senior years, many of us finally have the opportunity to reinvent ourselves. In fact, many of us have expanded options for choosing where and how we will apply our talents in work, play, and learning. But this involves determining which talents we want to continue putting forth as our strongest suits, which we want to discard or park off to the side, and which we want to pick up and explore. It’s time for the real you to stand up.

Reinventing Yourself Around Your Unique Talents

Reinventing Yourself Around Your Unique TalentsWhat do you excel at? What would you like to do more of? What have you excelled at in the past? What do you want to do a whole lot less of? Are there talents you would love to develop and activities you might enjoy but never had time for? Consider questions such as these as you graduate into senior life and reinvent yourself. If there is one thing I hope you’ll remember from this book, it is this:

You don’t have to continue doing something just because you happen to be good at it!

Let’s say, for example, that you are a senior finance specialist and are really good at it, but you often find yourself daydreaming about climbing Mount Kilimanjaro and organizing safaris. Pay attention to your dreams. They are worthy of serious attention. It’s all too easy to discount such images as nothing more that diversionary efforts of the mind to entertain you when things get a bit too routine. In fact, such mental images just might be messages from your inner self, communications from a deep wisdom center suggesting new life ventures. Don’t let complacency and a fixation on what’s practical overrule your fantasies. I’ve seen too many individuals, especially men, who’ve had successful careers, disregard their daydreams and slip into the life of a consultant because it seems easier or more practical to continue the same kind of work they were doing. Becoming a consultant is, of course, commendable if what you have been doing is a passion. If you’re doing what you love, why stop? But to continue in something you’re less than excited about simply because you are good at it would be like eating the same meal night after night simply because you think you can’t fix or afford anything else. Such limited dinner fare not only becomes tasteless but nonnutritional.

Reinventing yourself is risky and challenging, but taking on a new challenge can also be immensely rejuvenating. When was the last time you took on an engaging challenge, one that involved some adventure and risk? How did that feel to you at the time? What was your reaction to it in retrospect? Let’s face it, you and I are not going to be around this old planet forever. We don’t know if we have 10 or 20 or 40 more good years. Although two or three decades may seem long from the vantage point of the current moment, when I look back at my life, I see the decades speeding by at an ever-increasing rate. You owe it to your future self to reinvent your life in a way that will provide the future you with a sense of joy, accomplishment, and fulfillment.

If you have progressed this far in the book, you have already taken some big steps toward self-reinvention. You have engaged in some vision work, considered in what ways you will want to remodel your identity, and reassessed and possibly even reordered your values. Proceeding from here involves deciding which talents you want to feature in your new life. It’s time to specify which talents you want to leave out, which you want to develop in new ways, and which you want to move from the background to the foreground.

Talents are potentials that come in three general varieties: learning capabilities, natural abilities, and personality endowments. What you know—or your accumulated knowledge—is a function of your learning capabilities. Some of us can learn calculus, some trapeze artistry, and some slapstick comedy so funny that the audience can only gasp in laughter. The types of knowledge you have accumulated, along with the know-how you’ve acquired, indicate your particular style of learning. For example, you might have learned a lot about plant biology or baseball and know how to identify all the trees in the forest or how to figure out the batting average for every major league player. But you may not have the natural abilities or talents to grow award-winning roses or pitch for the Boston Red Sox. We come hardwired into the world with our talents and have life experiences that present us with choices and opportunities to develop them or not.

The same is true for learning capabilities. Some of us may be better equipped to learn about the photosynthesis of hybrid roses because we came endowed with a natural bent toward the kind of mathematical calculations needed to be a botanist. Or we could have been endowed with the proverbial green thumb—an inherent sense of the sun, soil, and moisture conditions needed for growing perfect roses. Same with baseball. I know a young man who was born with the ability to do large computations in his head and can recite baseball statistics ad infinitum. But, no matter how hard he worked at it, he’d never be a major league pitcher because he just wasn’t born with the kind of athletic ability that is required for striking out a great batter when all the bases are loaded and it’s in the ninth inning of the last game of the World Series.

Personality-wise, some of us are gregarious, some congenial, some intrepid, and others soulful. The better you understand the strengths of your personality, the more effective you can be in capitalizing on your natural gifts. We’ll explore that in more detail in the next chapter. For now, let’s focus on assessing what natural talents you have developed and might want to continue using (possibly in new ways), those well-developed talents you want to discontinue, and what’s lurking inside ready to be brought into the light of day.

Motivating Your Talent

Motivating Your TalentThe emerging view of human intelligence is that it consists of a broad array of different talents, as opposed to some universal type of general ability. Determining your real capabilities, therefore, is more complex than simply administering an intelligence test and deriving an I.Q. score. Talents also spread across an array of abilities, from left-brained analysis to right-brained intuition, from facilities for relating to people to learning languages to shooting balls through hoops.

But it’s not just what you’re good at that defines your personal gifts; it’s also a matter of connecting what you are interested in with your talents. You may be built to be a world-class swimmer, but if you hate the water, you aren’t likely to win an Olympic medal in swimming. The same is true for just about any type of human capability. For example, I worked with a client who was a brilliant accountant. She graduated with high honors, earned an MBA from a top university, and moved into a lucrative position. There was just one problem—she hated her work and had to undertake a career move to do something that was a better fit for both her talents and her interests.

I refer to this combination of talent and interest as motivated strengths. When you combine talent and interest in anything you do in life, whether work, learning, or leisure, you are going to be more energized, more engaged, more persevering (it’s hard to stop doing what you love), and more successful.

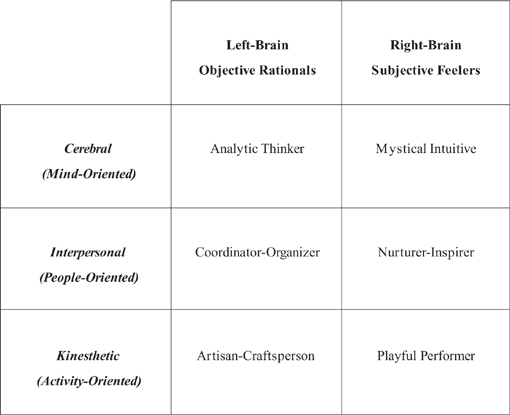

Over the years in my counseling practice, I’ve developed an organizing structure that has helped hundreds of individuals better understand and capitalize on their unique endowments of talent and energy. This structure separates strengths into six styles based on brain dominance (left/right brain thinking preference) and the characteristic ways in which people express their styles. A more detailed explanation of this process is available in my book Will The Real You Please Stand Up? I have also included a brief adaptation of the process here for your convenience.

The first feature of my organizing structure deals with dominance. One of the many amazing features of the human physiology is that many parts of the body come in sets of two—eyes, ears, arms, legs, and kidneys, for instance. We also have two hemispheres of the brain, left and right. Most of us develop a dominance of one side of the body over the other. Some of us are right-handed and some left-handed; some of us have right-eye dominance and some left; and some of us are more adept in right-brain functions and others in left. Brain dominance refers to the fairly recent discovery that most of us develop a preference for using one side of our brains over the other. Logical, objective thought process is the realm of the brain’s left hemisphere, while nonlinear, subjective, and intuitive thought is the specialty of the right. This concept of brain dominance, as I’ve come to understand it, is based in large measure on my study with Ned Herrmann, whose work is described in his books The Creative Brain (Lake Lure, North Carolina: Brain Books, 1988) and The Whole Brain Business Book (New York: McGraw-Hill, 1996).

The second feature of my organizing structure has to do with how people tend to focus and concentrate their energy. Have you noticed that some of us always seem to have our heads in the clouds? Those of us with this kind of focus may not even see you when we pass you in the hall because our energy is focused inward. It’s not that we don’t like you or aren’t interested in you—it’s just that our thoughts are focused in the frontal lobes of the cerebral brain, which we have engaged to solve some problem. With this inward focus, we’re probably not paying much attention to what’s happening in the here and now around us. We are the mental cerebrals. If you happen to be one, get your head out of the clouds right now and pay attention to what you’re reading.

Another way in which some of us are focused is in what’s going on around us, especially in our attention to others. Pass one of these folks in the hall or on the street and you know that they know you’re in their world. They may smile at you, say hello, or simply acknowledge your presence with a knowing glance. These are folks who need people, who interact with people, and who tell career counselors that they want a job working with people. I refer to those of us in this style as relationals. Their interpersonal relationships form the primary interest in their lives. If you fall in this category, you don’t want to end up spending your time in solitary research.

A third way in which we concentrate our attention and energy is in body-oriented activity. These are the kinesthetics, or activity-oriented individuals. They tend to be more attuned to their bodies and more action-oriented than those of us more intent on a life of the mind or interacting with people. A kinesthetic would much rather throw a ball than talk or think about it. When it comes to ballgames, the kinesthetic would rather play or be an active spectator, while the relational person would probably rather coach the team or use the game as a way to socialize with friends. The cerebral would probably prefer to invent a game or conduct a statistical analysis of it.

Combined, the brain dominance and energy focus dimensions generate six styles, as shown in Figure 7-1. Let’s look at each style in more detail.

Analytic Thinker Individuals favoring this style are most comfortable in the world of objective facts, analysis, abstract conceptualization, and cerebral problem-solving. They seek to understand their world through careful mental concentration based on the interaction between cause and effect. Their motto might be: All things can be understood through science. They are likely to see a world based on the laws of physics. They tend to mistrust intuition and the mystical because those realms are not rational. They also tend to be critical in their approach to life and work. They have a passion for rational thinking, attempting to discern what is true and what is false through detached logic. If you engage them in a problem, they can’t leave it alone until they can find a reasonable explanation or a logical solution.

FIGURE 7-1. SIX STYLES OF MOTIVATED STRENGTHS.

Coordinator-Organizer Those of this persuasion are most comfortable in the objective world of facts, information, and data. They have a passion for the practical and the efficient and distrust the intuitive and/or the emotional. They are motivated by productive, planned-for outcomes. Their motto would be: Develop a plan and work the plan. To achieve a desired outcome, they would organize people or resources to accomplish projects within a prescribed time frame and/or ensure that policies and procedures are followed. They like being in positions of control where they exercise authority over programs, projects, resources, and people. In work they are oriented to business situations involving management, administration, contracting, purchasing, or finance. In leisure life they gravitate toward coordinating events, managing things, and organizing people. If you give them a problem to solve, they will don their business hat and devise a practical solution, probably in consultation with a few authoritative sources.

Artisan-Craftsperson These are activity-oriented individuals energized by hands-on tasks that involve practicing a trade (mechanics, carpentry, landscaping), executing a technical skill (computer operations, medical technology, masonry), or performing in physically demanding occupations (competitive sports, military special forces, construction work). Artisan-Craftspeople exercise patience and discipline in doing physical things involving coordination, strength, and attention to detail. They tend to be good at trouble-shooting, fixing, building, executing manual operations, or performing technical activities. They might be found operating heavy equipment or complicated machinery. This might be their motto: Just git ‘er done. If you give them a problem to solve and if it involves some kind of physical or mechanical challenge such as hanging a door or fixing an engine, they will find an ingenious way of doing it. If, however, the problem involves some kind of a personal issue, they are likely to tell you to mind your own business.

Mystical Intuitive Individuals favoring this style enjoy and feel comfortable in the subjective world of ideas, possibilities, conceptualization, and imagination. They feel a strong proclivity for expressing themselves in writing, music, dance, art, or some type of creative entrepreneurial venture. They tend to trust intuition over analysis and look for truth from the inner realm of knowing rather than the outer world of facts and data. Their motto might be this: The world and its creator are wonderfully mysterious. If you give one of these folks a problem to address, be ready for out-of-the box ideas originating from the abstract inner realm of intuition.

Nurturer-Inspirer Individuals preferring this style favor the subjective world of values, feelings, and ideas. They have a passion for working with people. They tend to be warm and friendly and are often charismatic individuals with strong convictions regarding human rights and equality issues. With robust personalities and astute communications skills, they often gravitate to situations where they can influence the intellectual, emotional, physical, or spiritual development of others. This could be their motto: Of the people, with the people, and for the people. If you give them a problem to solve, they’re likely to engage a group of people in a discussion of the issue.

Playful Performer These are individuals who are energized by work and leisure activities that involve learning and performing routines. Playful Performers love to be engaged in an active performance that brings something alive. They tend to be sensuous, sentimental, impulsive, and spontaneous. They enjoy entertaining others, have a good stage presence, and instinctively understand how they impact others. They tend to make decisions based on their personal values, drives, and emotional make-up, rather than from detached logic. Their preference for people interaction and activity inclines them to occupations such as entertainment, customer service, coordinating public activities, and nontechnical sales. Their motto might be: Let me entertain you! If you give them a problem to solve, they will want to have fun with it, probably drawing on a proven method but adding a playful nuance to it.

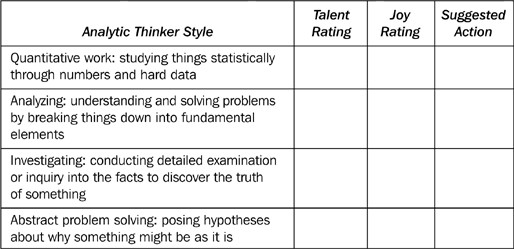

This assessment is designed to help you determine what strengths you might want to continue using, which it’s time to abandon, and which underutilized strengths you might now wish to develop. This assessment is organized into three parts:

1. Review the individual strengths within each of the six styles to determine your current level of competence in using the strength.

2. Rate how much you believe you would enjoy using this strength in the future.

3. Determine what future actions to undertake with these strengths.

Use the following rating scales for making these assessments:

Rating Your Competencies

Rating Your Enjoyment Potential

Use the following descriptions as aids in determining what suggested actions to undertake.

• Feature (F): those you rated 7 or higher in both the Talent and Joy columns.

• Develop (D): those you rated 7 or above in the Joy column, but 5 or lower in the Talent column

• Minimize (M): those in which you are highly competent but have little interest

• Avoid (A): those you rated 5 or lower in both Talent and Joy

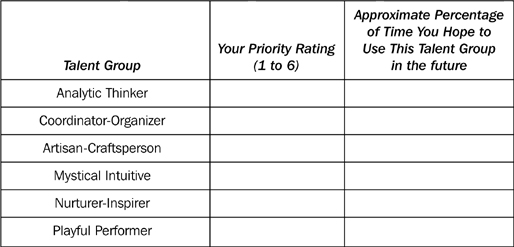

Prioritizing Your Favorite Talent Groups

Based on your assessments in the six groups of skills, determine which are your favorite talent groups. Rank them from your most favorite (#1 group) to your least favorite (#6 group).

After ranking these groups, make a rough estimate of how much you would like to be using these talents over the next three to five years in work, fun, and learning.

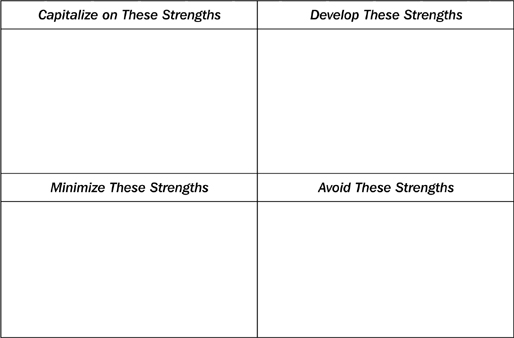

Summarizing Your Assessment Results

Use the following chart to summarize your results from the Motivated Strengths Assessment.

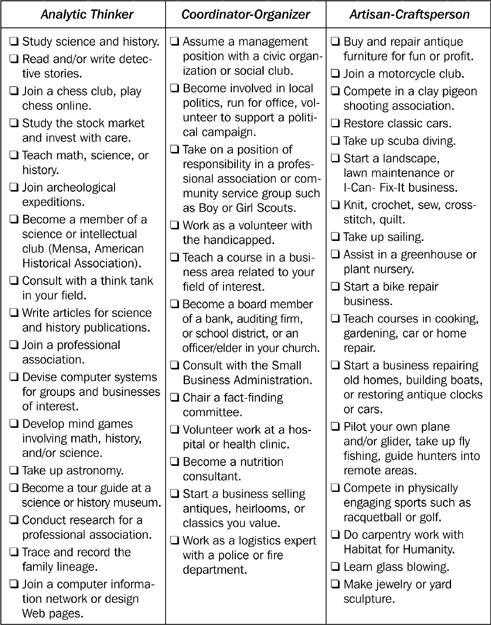

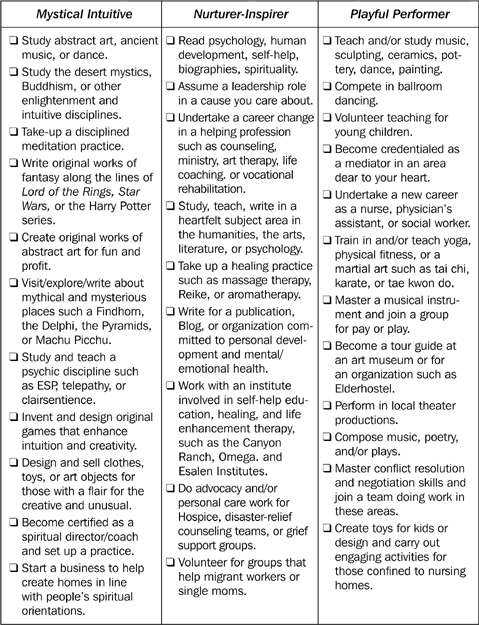

The following chart is provided for help in generating ideas in how you might wish to apply your preferred strengths in your future work, leisure, and learning. Check off the items that are of interest to you.

Sample Work/Volunteer/Learning/Leisure Activities for Left-Brain Styles

Sample Work/Learning/Leisure Activities for Right-Brain Styles

New Directions for Old and Underdeveloped Talents

New Directions for Old and Underdeveloped TalentsA statement I made earlier in this chapter bears repeating at this point: You don’t have to continue doing something just because you happen to be good at it! I know many people who have been successful in making a shift in the way they develop and apply their talents. Let me share a few examples to help spur your thinking about how you might use your own talents in new ways.

Ted’s Mystical Intuitive talents have been highly developed in his 30-year career as a writer and an editor for the National Park Service. Even after all those years in the “writing saddle,” he still loves to use his talent and skills for crafting clearly articulated prose. But he has also become a bit weary of confining his creativity to governmental structures. To remedy that and to provide a freer reign for his humor and creativity, he has found a way to use his creative talents as a journalist in a whimsical column for a community-based news magazine and as a poet who has been published in a number of publications. His gift for tongue-in-cheek commentary and satirical poetry has earned him the well-deserved reputation for being the town wit. As his government career becomes past tense, he is looking forward to being able to devote full-time to his passion for poetry and penchant for “reporting all the wit that causes a titter in print!”

Marla decided it was time to retire after 30 years of exercising her talents as a Nurturer-Inspirer teaching in the public school system. Before she made the big retirement decision, however, she had learned that a routine bone scan showed that she was in the early stages of osteoporosis. She took up yoga as part of her new health initiative and found that she loved the actual practice of it and the wonderful effects it had on her body and mind. She also began to realize that she had a real talent for the practice of it and soon became a serious student, eventually becoming a certified teacher herself. It wasn’t long before she retired from teaching social studies to middle school youth and began teaching yoga to adults of all ages. With her contagious enthusiasm and honed teaching skills, she quickly became a popular, well-respected yoga instructor and now recently opened her own studio.

Marla’s genuine delight in all her students is clearly evident, but she has a special place in her heart for her elderly students at a nearby retirement community. She feels good about being able to help them improve their mobility, overall physical health, and emotional well being. In addition, since retiring, she now has time to exercise her Playful Performer talents with an English folk dance group that performs for fun and entertainment at community events. Today, Marla is a vibrant personification of health and well-being and is having a great time helping others to feel great. What more could any Nurturer-Inspirer ask for?

Dianne is a dentist—or I should say, was a dentist—who after many years of tending teeth as Analytic Thinker and Artisan-Craftsperson decided that it was time for a new and different use of her time and talents. She has enjoyed transferring her gifts for analyzing and appraising and her skills for working with detail to a new venue—owning and operating a home accessory store specializing in vintage furniture, house and garden decor, and anything else that strikes her eye for the well-appointed home. She is also having fun in using her latent talents as a Playful Performer and Coordinator-Organizer to make her shop a popular stop for shoppers who like unique boutiques.

Fiona, a highly competent Coordinator-Organizer, decided to take an early retirement from her senior executive position with an international development organization to pursue a new endeavor as a Nurturer-Inspirer. In her role at the top of a large operation, she realized that she was enjoying coaching and mentoring her staff and other employees more than tending to her corporate management responsibilities. Prodded by that realization, she began to explore new career possibilities in the helping professions and eventually chose to pursue a social work degree. Although she had to face the incredulity of friends and associates who were shocked that she would even consider such a shift, she stayed true to her new course and enrolled in a graduate school program that would support her new career vision.

Today Fiona is a social worker pursuing her passion for helping international workers transitioning into the culture, customs, and legalities of a foreign culture. She enjoyed her years in the hot seat as a corporate executive, but she has no regrets about leaving her high-paying, high-stress position behind. The last time I talked with her, she said that she receives infinitely more satisfaction from helping one client at a time than she ever did in helping a large corporation make the bottom line.

Mike, at the age of 58, decided it was time to try something dramatically new and different. After a long and successful career as an international economist, he negotiated for a buyout from his company to try his hand at organic beef farming. His talents as an Analytic Thinker had been well-developed and applied as an economist working with entrepreneurial sectors of developing nations, but he had always harbored a secret desire to try out his own entrepreneurial talents and apply his Artisan-Craftsperson skills and Coordinator-Organizer abilities to a new venture. Currently he is five years into his new venture and is thoroughly enjoying the outdoor life that comes with raising choice cattle and managing a business that caters to discerning buyers. As an economist, he earned a generous income for working with leaders in the public and private sectors. Now, as his own boss, he is barely squeaking by financially, but has never been happier or healthier. He expects to turn the corner profit-wise soon, but he says his real payoff is the new experience and knowledge he is gaining, plus all the organic beef he can eat on the side.

Roundup Time

Roundup TimeIn your fifty-plus years, you are probably well positioned to make some life/work/leisure adjustments in order to play to the unique talent strengths you have that are energized by passion. Are you ready to let go of some of the things at which you have become rather adept but no longer particularly enjoy? Or would you like to use a well-developed talent in a new way or try out a talent you have not had an opportunity to develop previously but might now enjoy? At this stage of life, not only are you a person of many talents, but also you have most likely identified some uniquely personal interests. Do these talents and interests support and enhance who you are becoming? If not, this may be the best time of your life for connecting a talent, whether currently developed or not, with something that you value and that provides you with an energizing sense of enjoyment.

When you think about it, a phrase that many life-development counselors and coaches, including myself, often use—follow your passion—is rather passive. Your passion is not, after all, something you follow around from field to field as you try to round it up and herd it into a pen. Your passion is nothing less than YOU—it’s the ultimate expression of who you are. As dancer/choreographer Martha Graham said, “There is a vitality, a life force, an energy, a quickening that is translated through you into action, and because there is only one of you in all of time, this expression is unique. And if you block it, it will never exist through any other medium and it will be lost. The world will not have it. . . . You have to keep yourself open and aware to the urges that motivate you. . . .”1 In other words, the world needs your YOU-niqueness, and only you can bring it to its full expression. But doing so means that you must actively go for it!