For the Sulpician priest René-Charles de Breslay, it was more than a metaphor that the Indians had their French neighbors by the throat. Breslay lived near the southwestern tip of the island of Montreal, a few hours’ walk from a growing colonial town of the same name. He settled away from the French population center to minister to a small Nipissing Indian village that had risen at the confluence of the Ottawa and St. Lawrence rivers. Breslay called the village his mission, but the Nipissings called it home, suffering his presence there only after sustained pressure from their French commercial and military partners. Positioned in a small, if well-fortified, compound next to the Native town, Breslay lived as close to the Nipissings as they would allow, devoting his life to their Christianization.1

In the summer of 1713, his labors nearly cost him his life. As he had done many times before, Father Breslay confronted two Native men who had become drunk after buying smuggled brandy. There is no record of his words, but in writing he often complained of the social disorder created by drunken violence on the island and its harmful effects on his proselytizing. As he reproached the men for their condition, one of them snapped back at the priest, grabbing him by the neck and spitting threats into his stunned face. A sympathetic Nipissing man came to Breslay’s aid, freeing him from the grasp of his attacker and shielding him from further assaults. Walking away, the men insulted the disheveled priest in their native Algonquian dialect, knowing that he would understand them perfectly.2

Father Breslay was not amused. Invoking French laws forbidding public drunkenness and criminalizing Indians’ purchase of alcohol, Breslay demanded his attackers’ imprisonment. A recent murder had been traced to Indians’ alcohol consumption, raising Breslay’s already substantial alarm at the growing liquor trade—a fear made personal by his own assault. An influential man in Montreal, Breslay got his wish, and the two offenders were transported into town to sober up and prepare for trial. But everyone, including Breslay, knew that the men would walk out of prison the next day and face no further consequences. Not that the alcohol trade was taken lightly by French authorities: efforts to stop liquor trafficking had consumed both church and state administrators for the better part of fifty years. The king’s annual memorandum just months before advised colonial leaders that “one cannot give too much attention to preventing it.” Current French law prohibited selling liquor to Natives in all but the most closely controlled settings, and it never tolerated sales in local Native towns. But Indian communities surrounding Montreal made it clear long before that they would brook no attempts to subordinate them to the French justice system, threatening to turn to the English for alcohol—and alliance—should the French clamp down too hard. So French authorities wisely chose not to prosecute their Indian neighbors.3

Unable to punish Indians for liquor smuggling, colonial authorities settled on pursuing their French suppliers. At Breslay’s urging, Montreal’s royal court identified a suspect, François Lamoureux dit Saint Germain, a man the priest knew well.4 A gunsmith and minor merchant living in the heart of Montreal’s commercial district, Lamoureux had a well-earned reputation as a liquor and arms smuggler. He also owned a large plot of land adjacent to Breslay’s mission, which was the supposed staging ground for his smuggling operations. Within a few days the court built a strong case against him with eyewitness accounts of Lamoureux’s liberal supply of brandy, beer, cider, and wine to Indian customers. A few Indians, including a Mohawk named Oronhoua who may have helped Lamoureux smuggle liquor to local villages, provided essential details that all but guaranteed Lamoureux’s conviction. The judge seemed convinced of the two basic tenets of the case: that Breslay “was assaulted by drunken Indians and that the said St. Germain . . . had traded the brandy to the Indians.”5

Leading as it did to an attack on a prominent cleric, and not being his first offense, Lamoureux’s brandy smuggling could have triggered severe punishment: public flogging and a fine of up to one thousand livres, equivalent to almost seven years’ wages for a Montreal laborer. But as the case neared its conclusion after nearly five weeks of testimony, the court abruptly ended the proceedings, remitting all evidence to the procureur de roi, or king’s attorney, who rendered no verdict and issued no punishment. Lamoureux apparently had friends in high places, perhaps as high as the colony’s governor, Philippe de Rigaud de Vaudreuil, who clashed with other colonial leaders over his own alleged liquor smuggling and who would urge caution in turning away Indian customers for fear of their defection to the English. Whatever the reason, the court’s inaction ensured that Lamoureux’s arrest cost him little more than a few days’ time. In frustration, Breslay sailed for France to appeal directly to the aging Louis XIV, whom he had served as a young valet years before. As Breslay pursued his anti-brandy crusade, Lamoureux resumed business as usual, continuing not only the liquor trade but also unlicensed exports to French merchants in the west and smuggling to English and Iroquois traders at Albany.6 Despite the combined efforts of church and state, the liquor trade continued apace.

Read one way, Lamoureux’s trial offers a glimpse of the double measure of chaos that afflicted many frontier cities, joining the disorders of urban living to the unruliness of imperial hinterlands so distant from metropolitan order. As a site of violence, theft, smuggling, counterfeiting, illicit sex, and political corruption that seemed to penetrate all levels of society, Montreal certainly frustrated the designs of its absolutist architects. Independent Natives and defiant colonists, not wigged royals, defined the day-to-day realities there. “It is a world system,” according to Richard White, “in which minor agents, allies, and even subjects at the periphery often guide the course of empires.”7 And as James Pritchard has explained, smuggling in particular “illustrates the fragility of royal absolutism in the [French] colonies,” ensuring the persistent “weakness of metropolitan authority.”8

From this perspective, the dividing lines between state and subject, colonizer and colonized, seem fairly clear. King and priest stood united for imperial order against the raw and dynamic energy of frontier traders and Indians whose venal interests ran counter to the larger agenda of projecting French religion, law, and royal glory into new lands. The drunken Indian’s chokehold on Breslay could be read as a symbol of broader resistance to his mission of civilization under a Catholic monarchy. Both familiar and comprehensible, this story of frontier freedom striving against old-world absolutism has long appealed to those wishing to explain American distinctiveness. Caught up in the rhetoric of the American Revolution, late eighteenth-century political theorists set their freedom-versus-despotism morality play on the stage of the frontier fully a century before Frederick Jackson Turner unveiled his famous thesis.

Yet most recent work on frontier cities highlights the connections between colony and metropole, emphasizing continuity where others saw only rupture. Recognizing colonial cities’ dependence on European goods, markets, capital, and military defense, this scholarship portrays frontier cities as imperial rather than independent spaces. “In this new story of economic linkages between empire and frontier,” writes Jay Gitlin, “urban settlements become the spearheads of western settlement.”9 Striking at the wilderness and the Indians who lived there, urban frontiers proved particularly effective tools of empire and were thus critical to European expansion. In Richard Wade’s now-classic treatment, cities “held the west for the approaching population.”10 In the global geography of empire, this approach contends, cities were not primarily sites of imperial weakness: they were imperial strongholds.

Rather than a dichotomy between state power and local autonomy, Lamoureux’s case and its inconclusive outcome reveal that Montreal could be simultaneously independent and imperial, diverse and dynamic, but never far from European influence and state intervention. Montreal’s imperial geography invited, and indeed depended upon, frontier disorders for its success. Rather than a spearhead striking a threatening blow to Native communities to allow for the advancement of European settlement, Montreal was a critical nexus where Native, colonial, and imperial cultures came together and created mutual dependencies. In the imperial geography of the French empire, Montreal mirrored and magnified its natural history as a place of convergence, drawing far-flung peoples and resources together in the service of empire. The chaos that made Montreal function so well did frustrate imperial dreams of order and subordination, but it also allowed the state to insinuate itself into the lives of the very people who challenged its authority, drawing colonists and Native peoples into conversation with an expansionist empire in profound and disorienting ways.

French investors, administrators, and priests established Montreal for three related reasons. First seen by Jacques Cartier and Samuel de Champlain as a perfect location for trade and exploration, the island quickly became the source of great religious excitement. Established in the 1640s by the Sulpician order as a mission, the site also proved an important location for solidifying military alliances. During the late seventeenth century, Montreal developed primarily as a trade center, a place of exchange where furs from the west met manufactured goods from the east. By century’s end, the fur trade declined temporarily due to oversupply, but France’s need for Indian military allies reached an all-time high. These three fluctuating agendas—Montreal as mission, bastion, and entrepôt—often competed for ascendancy: priests condemned the short-sighted materialism of the town’s commercial activities, governors worried that priests would drive away their military allies, and merchants complained that both were destroying their profits. For all of their differences, though, each vision of Montreal needed the presence of Indians to succeed, yielding general agreement in Montreal that whatever else was done, Indians had to stay close by. Priests needed people to teach, merchants and settlers needed Indians’ goods, and military strategists liked having Indians on hand to strengthen the colony’s defenses. Indian peoples, then, were neither external nor even peripheral to the development of Montreal. Nor were they a necessary obstacle that the French intended to push aside. The success of the city itself, no matter whose vision of it prevailed, required Indians to be there in large numbers.

Eight times the size of Manhattan, the island of Montreal creates a choke point in the St. Lawrence River that provides both environmental and geo-political advantages to its human inhabitants. By narrowing the river channel the island forms what is now known as the Lachine Rapids: “the most violent rapid it is possible to see,” according to Jacques Cartier, who in 1535 became the first European to reach the island. Impossible to pass in a boat or canoe, the rapids made Montreal a strategic portage as Native and later French vessels landed on either side to skirt them. Montreal also guards the confluence of the Ottawa and St. Lawrence Rivers, forming a large and slow pool known as Lac des Deux Montagnes (Lake of the Two Mountains). Arcing over the northwestern section of the island, just north of the rapids, this gentle entrance into the St. Lawrence acted like a bay, providing relatively safe harbor to vessels coming down the Ottawa from the continent’s northern and western interior. To the southeast the island provided access to New York and beyond via the Richelieu River, which lies just ten miles overland to the southeast and meets the St. Lawrence thirty miles downstream. The island thus stood at intersection of water routes that linked the western Great Lakes via the Ottawa River with Appalachia and the Atlantic Ocean.11

Iroquoian peoples recognized these advantages long before the French. When Jacques Cartier arrived in 1535, he encountered an Iroquoian town of several thousand residents called Hochelaga, surrounded for miles by “fine land with large fields covered with the corn of the country.” The riverbank, village, fields, and surrounding forests were linked by a network of paths, “as well-trodden as it is possible to see.” At the end of one of these paths was the town, where Cartier was welcomed and feasted with an abundance that made plain the agricultural and commercial potential of this location. By the end of his visit, he concluded that it would be an excellent site for French settlement, as “the country was the finest and most excellent one could find anywhere.”12 Seventy years later, when French colonization gained renewed momentum, Samuel de Champlain agreed, proposing as early as 1611 a French settlement on Montreal Island near the natural portage point just downstream from the rapids. By Champlain’s time, Hochelaga had been abandoned by its Iroquoian residents, possibly due to disease or warfare from competition over European trade, leaving the island temporarily open for French settlement. Insufficiently funded and facing nearly constant warfare with the Iroquois, Champlain never acted on his plan, despite his hope that controlling passage through the St. Lawrence to Asia would bring vast wealth and glory to the French kingdom “inasmuch as the merchants of all Christendom would pass through.”13

Montreal was eventually settled in 1642 by the Societé Notre-Dame de Montréal pour la conversion des Sauvages de la Nouvelle-France, a group of Catholic mystics who envisioned the island as a frontier mission, a dangerous but divine post that would draw Native families for spiritual and physical healing. The Society acknowledged the need for a town and farms on the island to provision the mission, and to give a critical mass of settlers for the missionaries’ security, but the settlement’s purpose required that Indians be drawn to Montreal rather than being pushed aside. Merchant interests supporting the enterprise also saw the advantage of attracting Indians to the island, making it a key gathering point for dispersed sources of furs and a convenient location for plying Native customers with French goods. Recognizing both spiritual and secular advantages, the Jesuit priest Barthélemy Vimont declared that the island “gives access and an admirable approach to all the Nations of this vast country . . . so that, if peace prevailed among these peoples they would land thereon from all sides.”14

But peace did not prevail, making Montreal’s centrality its greatest liability as well as its best asset. Drawing Native allies also attracted their Iroquois enemies, who needed little encouragement after several French attacks in the previous decades had grown out of France’s alliance with the Iroquois’ Huron enemies. One early planner expressed the sense of foreboding felt by many potential French settlers of Montreal, who feared that at any moment “all the trees of that island would change into as many Iroquois.”15 One measure of this fear was the fact that the Society had obtained the island for free from the company that controlled New France, whose associates recognized the site’s potential but thought no French settlement there could survive the Iroquois threat.

French-Iroquois relations defined Montreal’s early future far more than its proselytizing spirit, making it more of a bastion than a mission in its formative years. During the first decade of settlement alone, surviving records document more than one hundred clashes between New France or its allies and the Iroquois. Regular Iroquois raids in the early 1640s exploded into a massive onslaught between 1649 and 1652 that obliterated most Huron settlements and brought the entire French colony to the brink of destruction.16 Montreal was especially exposed because of its tiny population and lack of proper defenses, and because it was the only French settlement west of the Richelieu River route taken by Iroquois raiders. The French population therefore grew very slowly. In the 1650s Montreal was home to only a handful of houses clustered at the site of the future city and a scattering of farms strewn across the island and on the banks of the St. Lawrence. By the time of the colony’s first census in 1666, after nearly a quarter century of settlement, only about 650 French colonists inhabited the entire island. The town itself had only about 30 houses and just over 150 residents with no palisade or even clear boundaries to set it apart from its rural surroundings.17

With a combined force of colonial militia, regular troops, and Native allies, the French bludgeoned the Iroquois to the negotiating table, concluding a peace that took hold in 1667. Over the next forty years Montreal’s population—both French and Native—rose dramatically as the town of Montreal took shape alongside several Indian towns that relocated to the island at this time of relative calm. The simultaneous rise of French and Indian settlements was no coincidence. They relied upon and fed one another, each a walled enclave linked in a larger island community that could not have existed without both colonial and indigenous elements.

Several Indian towns grew around the island and on its surrounding shores. The largest and most vibrant was known as Sault Saint-Louis by the French and Kahnawake by its Mohawk settlers. Located on the south shore of the St. Lawrence River just across from Montreal, this settlement began with little more than a dozen Iroquois Christians who left their villages in 1667 to avoid factional conflict over their acceptance of Christianity and their embrace of the French. If the earliest residents were drawn by their faith, the later and larger group of migrants came for the freely available land and, most importantly, the presence of a growing French town which could provide European goods and military defense. The 1660s was a decade of chastening for the Iroquois, leaving many with little but charred farmland to sustain families torn by factional conflict. Montreal promised a new beginning. And for the pro-French factions within Iroquoia it offered a path to pursue their interests without the interference of their Anglophile kin. Encouraged and provided land by the Jesuits, this small group slowly swelled to several hundred in the 1680s, and reached more than a thousand by 1700.18

A handful of smaller Indian villages appeared around the island at about the same time. The most diverse village was La Montagne, just northwest of the French town, settled by fragments of Huron, Iroquois, and various Algonquian-speaking nations in the late 1670s. We know very little about the nature of this town in the seventeenth century, but by Lamoureux’s time there were two to three hundred residents living in ethnic clusters near a fort which contained a church and a small garrison. Sault au Récollet, situated to the northeast of the French town, was meant as a refuge for Christian Indians but ended up attracting a group of mixed religious sentiments and a range of approaches to French cultural integration that created internal tension on issues like liquor consumption. Along with the Nipissing village on Isle aux Tourtres and several smaller, seasonal villages erected during the spring and summer months, the Native population rose dramatically during the final quarter of the seventeenth century, surpassing two thousand permanent or semi-permanent residents by 1700.19

The colonial town of Montreal grew with its neighboring Indian towns. As the Iroquois threat subsided during the 1670s, its advantageous location drew merchants, missionaries, and enterprising craftsmen to settle there. The island’s total French population reached 1,400 by 1681 and about 3,000 by 1700. During these years the town of Montreal took shape, growing from a cluster of about 30 homes in 1665 into a respectable colonial town of about 1,600 just forty years later, with a large portion of the growth occurring in the short span between 1686 and 1693. Larger than any individual Native village around the island, the town’s population was still outnumbered by the combined population of Native towns surrounding it. And this was just how colonial officials wanted it. Not only did a close body of Native allies provide military security, but they also drew pelts and goods to the French that otherwise would go to their English rivals. As consumers of French goods, and traders who re-exported French goods to other Native villages, Montreal’s settled Indians proved as essential to the town’s commercial success as to its security.20

The physical form of Montreal drew upon the island’s natural and Native histories as it transformed from mystical dream to practical reality. Placed at an inlet along the island’s southern edge, the town took advantage of an inward flow in the river’s current ideal for loading and unloading cargoes. The spot was, in fact, the site of a long-standing Indian portage road that early French maps identify as “Chemin de Lachine,” or the Lachine Trail, which later developed into an important colonial road in the eighteenth century linking the city to the island’s western settlements. The earliest buildings on the town site clustered along the Chemin de Lachine, which eventually became Rue Saint-Paul, home to most of the town’s merchants and their warehouses. Another Native path, quite possibly one noted by Cartier leading to the base of Mount Royal, connected Montreal to the Indian town at La Montagne. Within town the “chemin des sauvages de la montagne” became Rue Saint-François-Xavier, which ran alongside the Sulpician seminary to meet Rue Saint-Paul near the port. At the intersection of these Native paths, renamed for Catholic saints and squared by imperial surveyors, stood the Place du Marché, or market square. Linking the island’s northern interior to its western terminus, these paths also represented the joining of Native and colonial worlds that characterized Montreal’s early history. As the last point to unload cargoes from the east and the first safe point to re-enter the river after skirting the rapids from the west, the city’s commercial advantages combined with its human geography to facilitate trade between the Atlantic and the North American interior.21

But Montreal did not urbanize spontaneously. During the 1680s French officials mandated urban density by prohibiting private ownership of large tracts of land within the town’s boundaries, which were precisely defined between 1686 and 1693 with only minor modifications thereafter. French-Iroquois relations began to deteriorate again in 1684, raising alarm at the scattered and poorly defended condition of the town. With so much of the land claimed by so few proprietors, it was also impossible to develop a critical mass of residents and services for a functioning market town. In 1688 New France’s intendant, or chief civil and legal official, explained that building the city would provide the necessary amenities for a growing population and provide a place for them “to take cover from the attacks of the colony’s enemies.” One year later, a devastating attack on Montreal island by fifteen hundred Iroquois warriors only heightened the urgency of developing Montreal and its defenses, and a mostly wooden palisade was completed by the mid-1690s. By 1701, when the Iroquois met in Montreal to establish a lasting peace with New France and its Native allies, the town they entered was substantially different than the one they visited in the 1660s, having developed from a scattered mission village to an urban center on the rise. In its search for military protection and economic stability, Montreal’s urbanization mirrored the town building of its Indian neighbors.22

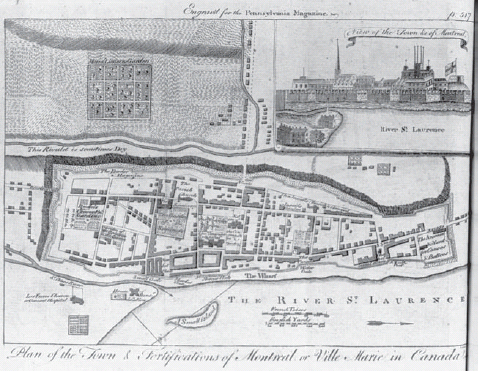

Figure 3.1. Robert Aitken, “Plan of the Town and Fortifications of Montreal, or Ville Marie in Canada,” 1775. Courtesy Library of Congress.

By 1713 when Lamoureux and his Native partners smuggled brandy to the Nipissing village, there were about four thousand French settlers in the Montreal district and around two thousand settled Indians: one thousand at Kahnawake and another thousand at other settlements around the island. When combined with the Native peoples who came to Montreal to visit relatives, trade with French and Indian settlers, or hold diplomatic meetings with French officials, Indian populations approached parity with their French neighbors. In the broader context of the upper St. Lawrence Valley and Great Lakes, of course, Indian peoples were far more numerous.23

Because most Indians visited the city more often than rural French settlements, colonists living within the town interacted with Indians far more than those living in the countryside. Mohawk women came to Montreal to visit French chapels, Nipissing men brought deer meat to the market square, Oneida families visited their French friends, enslaved Apache girls carried water to the garden. One could hear a dozen or more Amerindian languages spoken around the island in 1713, especially three Algonquian tongues—Anishinaabe, Nipissing, and Abenaki—and two Iroquoian languages—Mohawk and Oneida. Beginning in 1713, hearing Mesquakie became more common as a large number of enslaved Fox Indians came to Montreal, followed by dialects spoken by a growing number of Apache and Sioux slaves who arrived in the 1720s and 1730s.24

François Lamoureux was both a product and a proponent of the close relationship between Indian and French frontier towns in the St. Lawrence Valley. And despite his flouting of French law, he used those relationships to link colonists and Indians alike to the French imperial state that structured their lives even as it failed to control them. By understanding his smuggling operation and the relationships that made it possible, we can see beyond the fact of Indians’ presence in Montreal to the familial, geographic, and commercial dynamics that bound Indians and colonists in a web of interdependence spun by colonial forces beyond their control.

According to most surviving records, including the trial transcript, Lamoureux fit the standard profile of a petty merchant in eighteenth-century Montreal. Born and reared in Canada, Lamoureux married a slightly younger woman, fathered several children, and settled in a modest stone home on Rue Saint-Paul in the city’s commercial district. Not unlike many of his neighbors, Lamoureux had a tract of land outside town which he inherited from this father. He and his tenants grew wheat and other crops there for food and occasional sale or barter. The Lamoureux family was devoutly Catholic in every outward way. His wife, Marguerite Ménard, claimed to attend mass several times a week, and the couple saw to the religious education of their young. Both Lamoureux and his wife acted as godparents for their friends’ and neighbors’ children.25

Although no one at his trial mentioned it, Lamoureux’s connection to the island’s Indian community went well beyond commerce. He was himself the product of French-Native intimacy, embodying the ties of kinship that were so central to his trade. His father, Pierre, was a fur trader and his mother, Marguerite Pigarouiche, was an Algonquian-speaking Indian (of an unknown nation) born in the mission village of Sillery near Quebec. Lamoureux would have learned to speak his mother’s Algonquian dialect from his youth, explaining his facility with the many Algonquian tongues he mastered as an adult trader. It is likely that Lamoureux’s grandfather was Étienne Pigarouich, the famed Algonquian Christian who made several prominent appearances in the Jesuits’ Relations as a model convert turned apostate and then back again. Pigarouich offered such a moving public confession in the rough chapel at Montreal in December 1643 that many in attendance judged him equal to the priest who had given the formal sermon. The church’s translators claimed Pigarouich’s eloquence outshone their abilities: we “can only stammer in comparison with this man.”26

For three generations, by Lamoureux’s time, Catholicism had built a substantial community between many Indians and French. Beyond the fact of shared communion, which had a range of inconclusive meanings for Indian Catholics, Catholic ideology and the rites that emblematized it produced a network of fictive kin relationships that linked French and Native Catholics through godparenting. Lamoureux’s sister, Barbe, for example, was the godmother of Louis, son of Oukiakouamigou and Marie Nikens, both Algonquians, most likely from La Montagne. Lamoureux’s neighbor, a merchant named Louis Babis, acted as godfather. Lamoureux’s stepmother, Barbe Le Scel, acted as godmother to the son of Michel Keskabikat and Marie-Madeleine, Algonquians (probably Nipissings) from the west end of the island. In fact, the victim and accuser in Lamoureux’s trial—Father Breslay—performed nearly all of these baptisms, becoming a broker of French-Indian kinship, and who, despite standing outside these relations, exercised at least some cultural power over them. Just one month before he accused Lamoureux of smuggling, he presided over the baptism of a Nipissing girl christened Françoise. Her godmother was Lamoureux’s wife. These acts may have sometimes linked the Lamoureux family with their biological Algonquian relatives, but more often they created a new kind of kinship that bound them by ritual rather than blood. At a minimum, such records demonstrate that French, métis, and Native communities maintained close contact with one another across a wide spectrum of settings never restricted to trade. And for some, these acts must have both reflected and reinforced those relationships through the culturally powerful symbols of Catholic ritual. Surviving records do not provide a direct, one-to-one correlation between Lamoureux’s kinship—real or fictive—and his smuggling, but in places where such records survive these relationships produced commercial as well as familial connections.27

Commerce did not rely on Catholicism, however, but acted as an independent draw to Montreal’s urban center. According to witnesses in Lamoureux’s trial, an almost constant stream of Indian men and women flowed down Rue Saint-Paul into Lamoureux’s home and warehouse. Lamoureux made no attempt to deny this element of others’ testimony; to do so would have been futile. Instead, he acknowledged that “many Indians frequent his house” but protested that they were doing legitimate business there. It was a plausible defense, especially given Lamoureux’s licensed profession as a gun seller which attracted a steady clientele of St. Lawrence Indians who used the weapons for hunting and defense. As a petty merchant, Lamoureux also ran a constant business of small, in-kind exchanges with individual Indian partners, a pattern several witnesses mentioned without ever suggesting it was out of the ordinary.28

But for the presence of the frontier city, Lamoureux would have nothing to smuggle and no pretext for trade that would cover his tracks. The city’s geography, built to take advantage of Indians’ historical trade routes and designed from its beginning to attract Indians, simultaneously allowed for greater Native influence and provided surveillance that was impossible when trade occurred elsewhere. Lamoureux had one home within the walled centre ville, or downtown, of Montreal, on Rue Saint-Paul, the city’s chief commercial street built on the old Lachine Trail. French authorities had built a wall around the city to repel Iroquois attacks, but during the first half of the eighteenth century, it mostly functioned as a means of controlling traffic into and out of the city. Soldiers posted at each of the city’s gates inspected goods, checked papers, and questioned anyone who seemed not to belong. But the soldiers knew that Indians did belong in the city, so they rarely interfered with their passage into and out of town. What is more, like all merchants on his street, Lamoureux may have boarded the soldiers who monitored the ports, placing him in a position to influence the degree of their scrutiny. He also lived in an especially advantageous position along the city wall, with his backyard abutting the temporary Indian villages erected each summer for trade and diplomacy. One record indicates that he may have even owned some of the land used for the encampment.29

Through various witnesses we learn the identity of a few of Lamoureux’s regular Indian visitors. There was an Iroquois man from Kahnawake that the French dubbed “La Raquette,” or Snowshoe, because they had difficulty with his Iroquois name, which different witnesses rendered as “Taouingarrou,” “Toriniata,” and “Caoingaront.” A day laborer named Jacques Arrivé testified that he had seen Snowshoe the day before the assault as they both visited the same friend, Jean Quenet. Snowshoe was carrying two moose skins, which he then took to Lamoureux’s house. Until the Iroquois trader showed up with alcohol, nothing about these events seemed out of place. Quenet’s wife, Therese Hurtubise, seemed surer than Arrivé that Snowshoe had traded the skins for brandy but otherwise confirmed his account.

Another of Lamoureux’s trade partners was Oronhoua, a known Mohawk smuggler from Sault-au-Récollet rumored to be one of Lamoureaux’s middlemen. Oronhoua testified before the court despite French rules forbidding an Indian to testify against a French subject. During the 1710s colonial administrators debated the wisdom of this prohibition, especially since Indians themselves were in the best position to know who was smuggling alcohol into their villages. A man named Lalande suspected the involvement of Makougan (or Mak8a8an) and Sigo8ch (or Sigoouitz or Sigoouy), both Algonquian-speakers from Sault-au-Récollet. He had seen all of these men at Lamoureux’s home on Rue Saint-Paul, although he admitted to having no firsthand knowledge of the alcohol trade itself.30

Two Indians lived permanently with Lamoureux: his slaves—Joseph and Suzanne—who did his household chores, cared for his animals, stocked his warehouse, and cooked his meals. Suzanne regularly watched Lamoureux’s children, and Joseph traveled with him on trade journeys (often illegal ones) to Michilimackinac, Detroit, or Albany. Both Lamoureux and his slave Joseph were prosecuted for unlicensed and illegal trade more than once.31 One witness in the liquor trial testified that, since Lamoureux’s slave Joseph commonly carried goods around town for his master, he was able to smuggle casks of liquor in large bags designed for carrying trade cloth.32

We learn almost nothing from the trial record about the Nipissing drinkers. Their testimony was recorded quickly to facilitate their speedy return home. Pressure to release them came quickly. Barbe Perren testified that she received a visit the day of the arrest from a Nipissing woman she knew who was married to one of the drinkers. Angered by her husband’s arrest, she walked to town to demand his release from the unjust detention, insisting that her husband “had said nothing to M. de Breslay.” Women played an important diplomatic role in community relations between French and Native towns around Montreal Island. More women than men embraced Catholicism, for example, giving them greater credibility and sway with French clerical and low-level imperial officials. And informal emissaries like this one often accomplished more than formal diplomatic negotiations.33

The Nipissings’ translator, Simon Réaume, was part of a well-connected western merchant family who spoke most of the central Algonquian languages plus the relatively similar Nipissing. Réaume’s family had forged bonds with Ottawa and Illinois families through marriage, including his brother’s marriage to a prominent Illinois woman that paved their family’s path to trade in that region. Réaume lived across the street from Lamoureux, on the same block of Rue Saint-Paul (although he also maintained a residence in the Illinois country). Involved in the same trade and passing each other daily on the street, Réaume was a competitor in western trade with every incentive to translate the Nipissings’ words to Lamoureux’s condemnation.34 But Réaume was hardly participating from a position of innocence: he had himself been tried for smuggling just five years earlier, and he appeared in liquor trafficking cases as translator and possible participant within two years of Lamoureux’s trial.35

Lamoureux’s sixteen-year-old neighbor, Marie-Anne Fafard dite Macouc, also testified that she had often seen and heard about Lamoureux’s supplying brandy and other alcoholic beverages to Montreal’s Indians. On one occasion, she told the court, she was returning to Montreal from Detroit. When they reached the island from the Ottawa River, they came ashore on Lamoureux’s land, where they found nine beached canoes, “both Indian and French.” On closer inspection, she found Lamoureux and several Indians lying in the canoes with their liquor, and “the Indians that were with them so drunk that they did not know where they had gotten it.” Belonging to a well-known métis family from Detroit, and a cousin of the far-flung and well-connected Mon-tours, Marie-Anne’s visit to her Anishinaabe kin was as routine as Lamoureux’s sleeping in a canoe with Indian traders.

Their meeting at the edge of the island hints at the impossibility of colonial officials’ imperative to control illegal trade, a task that seems all the more difficult when considered with the other routine traffic to and from Lamoureux’s home. Residents of every Native village around the island had some connection to this métis smuggler, either by kinship, religion, or trade. The Indians’ presence, as necessary as it was to Montreal’s purpose as a frontier city, frustrated some of the city’s imperial ambitions. But the city was also essential to the colony’s larger goal of attracting and maintaining Indian commercial and military partners. Lamoureux had what these Indian communities wanted, and to get it (or others’ versions of it) they had to come to the city, building the relationships that facilitate trade on both sides of the cultural divide. Paradoxically, then, the very smugglers who evaded particular imperial controls played a prominent role in ensuring Indians’ attachment to empire itself.

Just one of Lamoureux’s many illegal trade voyages to the west, five years before the trial, underscores the influence of Montreal and its smugglers on the insinuation of empire into Indian communities. In 1708 Lamoureux obtained a license to go into the backcountry to hunt, but instead he used the trip to smuggle English goods to Detroit. He had bought the contraband from neighboring Indians, most likely from Kahnawake, who had traveled from Albany to Montreal with their cargo. Going directly to Detroit via Lake Erie would have been much more efficient, but Montreal offered the security of a guaranteed market and the abundance of French goods, including brandy, that the Native smugglers wanted. Colonial administrators worried about men like Lamoureux, but they also counted on them to maintain Indians’ interest in coming to French places and maintaining French partnerships. From an imperial standpoint, the draw of the frontier city, even when that draw circumvented royal policy, accomplished imperial objectives as it rejected imperial authority.36

It was the smugglers’ ability to tie Indians to the empire that made Lamoureux and his kind so difficult to prosecute. This was less because the empire was unable to punish its rogue subjects than because some imperial strategists understood smugglers’ importance to France’s global ambitions. Just one year after Lamoureux’s trial, New France’s governor and intendant wrote a joint letter to the king urging him to relax prohibitions on the brandy trade. “The English draw a great advantage from their brandy trade with the Indians,” they explained, “which is such a great attraction to them that by this means the English attract the greatest portion of their pelts . . . [not having access to French liquor, Indians go to Albany] where they take all their beaver, which creates an open trade between them and the English.” Should French merchants fail to compete in this market and thus attract Indians to Montreal, they feared that the English “will draw them all [away], to the Ruin of the Colony.”37 The battle over liquor smuggling was thus not a competition between independence and empire, but a debate over the best means of insinuating empire into a distant continent. For his supple, if self-interested, response to such challenging questions, Vaudreuil received the reward of a grateful kingdom, garnering highly coveted colonial appointments for his sons, who governed Louisiana, New France, and St. Domingue during the 1740s and 1750s. However it was accomplished, maintaining Indian alliances in New France produced tangible rewards for Vaudreuil that tied his family to the interests of the French state for generations.38

Father Breslay was unwilling to accept this devil’s bargain. First through letters, and then during his personal visit to France, Breslay castigated New France’s officials for their tolerance of liquor and other smuggling, a campaign that bore little fruit. Breslay’s paternalistic chauvinism may grate on modern ears, but his invocation of French law to limit the brandy trade and its influence over Native peoples may have made his the most anti-colonial voice in the conversation. With his objections noted but ignored, Breslay was encouraged by the French crown to return to New France and continue working with the Nipissings, Abenakis, and Ottawas who lived near his mission, as long as his mission did not interfere with the security of the colony.39

When he returned from France in 1714, Breslay was resigned to pursuing his war against alcohol quietly from within the church. A task soon fell to him that must have strained his commitment to civility. In August 1715 Lamoureux brought his one-day-old son, François Charles, to the parish church at Sainte-Anne de Bellevue for baptism. Breslay not only baptized the child, but also acted as the boy’s godfather, a highly unusual role for a parish priest. For a single ritual moment, Breslay and Lamoureux joined in recognition of their mutual commitment to a cause that transcended their personal disputes.40 Whether they knew it or not, their lives had been similarly linked in the larger mission of the French empire as they pursued competing, but somehow complementary, visions of French imperial expansion.

It is now commonplace to view historical frontiers as complex zones of cultural interaction and innovation rather than dividing lines separating colonizer and colonized. As mixed and often independent spaces, frontiers are also generally characterized as either non-imperial or anti-imperial, inspiring a flurry of metaphors from the natural (tails wagging imperial dogs) to the technological (broken imperial machines).41 As Lamoureux’s Montreal suggests, zones of cultural accommodation could work within, and even strengthen, broader imperial strategies designed to extend imperial power. Although it stood at the farthest reaches of the French state, Montreal expanded the influence of that state not through violent exclusion or expulsion, but by inclusion and invitation. Montreal worked—for the French as much as for Indians—precisely because its walls were porous and its streets filled with those on the other side of the imaginary cultural border. Montreal worked—for the Indians as much as for the French—because it maintained intimate connections to France.