Estwick Evans worried about New Orleans. A New Hampshire native who engaged in a lengthy passage through the northern and western borderlands in 1818, Evans expressed those fears in a detailed narrative of his travels. When it came to New Orleans, the quintessential frontier city, Evans asked “will not our citizens . . . more readily imbibe, and more freely communicate the corrupt practices of this place? But, if by the praiseworthy conduct of our citizens residing in New-Orleans, immorality shall be checked, and good principles introduced, then, indeed, it will prove a purchase, not only for our country, but for mankind.”1

What do we make of this passage? At first glance, Evans’s worries seem to be the typical ranting of so many New Englanders who saw in the frontiers of North America the corruption that emerged when civilized Anglo-Americans came in contact with the decivilizing trifecta of Catholic religious culture, French and Spanish political culture, and multiracial contact culture. But remove “New Orleans” from the picture and this could well read like Thomas Jefferson’s tirade in Notes on the State of Virginia that “the mobs of great cities add just so much to the support of pure government, as sores do to the strength of the human body. It is the manners and spirit of a people which preserve a republic in vigour. A degeneracy in these is a canker which soon eats to the heart of its laws and constitution.”2

That similarity is more than coincidental and, in the end, not nearly so problematic as it may appear. It seems impossible to tease from Evans the threads of his commentary on frontiers from his commentary on cities. Yet the confluence of the two goes a long way toward explaining not only how Evans described New Orleans, but more generally how American print and visual culture went about constructing the cities of North America’s frontiers.

With that in mind, I would like to explore how frontier cities entered the American imagination through a series of travel narratives and maps published during the early American republic. To that end, this essay employs many of the same sources as the other participants in this volume, but for different purposes. Much of the best work in political, cultural, and social history has sought to extract the lived reality of North American frontiers from a set of deeply problematic texts. This work has sought to separate the wheat from the chaff, extracting a limited amount of believable information and discarding the large amount of extraneous or inaccurate material. I don’t envy the challenge of scholars who must disentangle a historical narrative about people who left few written records of their own from the cultural baggage that Europeans and Euro-Americans carried with them to the frontiers of North America. Indeed, my goal is to treat those problems as opportunities. I want to situate all the downsides of printed sources—the skewed perceptions, the misunderstood moments, the self-serving racial stereotyping—at the center of a discussion that will examine not only the cultural attitudes that informed how people described frontier cities, but the generic conventions that informed how printed and visual texts further determined that description.

I emphasize this focus on travel narratives and maps from the early republic because scholars in a broad range of fields have long announced the important role that images of the West would play in American culture, but they have usually opted for other objects to explain the representation of frontier cities. They have long emphasized the importance of self-defined artists, especially novelists and landscape painters. Likewise, scholars have tended to gravitate toward the antebellum era, in large part because that was exactly when those novelists and landscape artists turned their attention to the West. The late colonial era and the early republic tell a very different story. Maps and travel narratives would play the dominant role in visualizing frontier cities. Meanwhile, the people who produced those objects never considered themselves artists. Instead, it was a disconnected cohort of mapmakers, travelers, explorers, publishers, and part-time writers who shaped how Americans conceived of the West in general and frontier cities in particular.3

Equally important, mass-producing the maps that were such an important part of describing frontier cities was extraordinarily difficult in the United States, and this technical matter also separates the early republic from the antebellum era. Although the United States enjoyed a robust capacity to mass-produce the printed word, it had only a limited capacity to mass-produce maps, or for that matter any other visual images.

As a result, I am less concerned with the realities of intercultural contact that are so often at the center of the scholarship about frontiers than I am with the ways printed texts struggled to establish typologies for frontier cities.4 I want to discuss the ways that published accounts of frontier cities were pulled in different, often opposing, directions that reflected a broader debate about how to understand frontier cities. At one moment these were places on a frontier, at least as frontiers were understood by Euro-American observers in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. The texts that described these places deployed the familiar terminology of frontiers: the line between civilization and savagery, the absence of cultural sophistication, the chronic underdevelopment. At the same time, these were cities, and as such seemed to exist outside frontiers. Frontier cities were imagined with closer connections to distant metropoles than to their immediate surroundings. Accordingly, these printed and visual texts deployed another vocabulary no less contrived and predetermined than the language they used to describe frontiers. Cities could embody sophistication, development, and above all civilization, but they could also be locations of corruption and decline.

Within this ambiguity, these texts engaged in a battle about whether frontier cities could redeem or endanger the republic. That debate often turned on the degree to which these places fit within models of frontiers or of cities. To some observers, frontier cities represented the worst decivilizing elements of the frontier. For others, the frontier provided the means to redeem the city. That was certainly the case for Thomas Jefferson, who advocated the creation of towns on frontiers not simply as a way to stimulate regional development, but also with the expectation that frontier settlers could prevent the corruption he associated with eastern cities. Finally, cities might provide the means to redeem frontiers. Estwick Evans certainly hoped so, believing that a city could civilize a region endangered by a host of frontier evils.

The growth of frontier cities therefore proceeded on a trajectory adjacent but not identical to the growth of white settlement more generally. The United States developed a particular language for celebrating the settlers who built farms on distant frontiers. Cities were something different. For some, the city was the necessary safeguard for the settler, preventing geographic and cultural isolation. For others, the farmer was the necessary safeguard against the city, guaranteeing that the frontier would be the home of white freeholders rather than the corrupt denizens of an urban landscape.

But understanding these issues of content only works with appropriate attention to issues of form. The representation of frontier cities within texts emerged not just at a particular moment in frontier history, but also within a particular moment in publishing history. The capacity to describe frontier cities in published form responded directly to the generic conventions and technological limitations of American publishing in the early republic.

The breadth of this published record would explode the confines of any paper. After all, describing frontier settlement became part of the publishing tradition in the Atlantic World from the moment Europeans first encountered the Americas. So for purposes of precision—and brevity—I have chosen to focus on texts produced within the United States during the half-century following independence. I make some reference to work of Europeans, especially those texts that influenced Americans or circulated widely within the United States. But this remains fundamentally an American story, discussing how the representation of frontier cities informed the ways that Americans described themselves.

In chronological terms, I begin this discussion with the last quarter of the eighteenth century, when Americans struggled to describe frontier cities in the face of considerable technical limitations. I then shift to the early nineteenth century, when American publishing acquired far greater capacity for western description, a technical development that coincided with international and domestic changes that transformed the boundaries and politics of North American frontiers. Finally, I close by considering the far-reaching changes of the antebellum era that transformed not only the reality of frontier life, but also the representational tools available to Americans.

At the heart of this discussion is not only the meaning of frontier cities, but more generally the definition of frontiers. Describing frontier cities in print and visual culture fits within a broader project of claiming North American territory. Perhaps so, but that story of conquest too easily overshadows the complex and contingent ways in which Americans struggled to locate—in every sense of the term—the cities of North American frontiers.

Understanding how Americans described frontier cities begins not with the people who actually created those descriptions, but rather with the publishing industry that circulated the information. As much as any subject, the media proved no less important than the message. An image (or, rather, a set of images) of frontier cities emerged through a highly specific set of print and visual traditions, technological limitations, economic pursuits, and policymaking imperatives. The limited capacity of American publishing initially meant that the visual and, to a lesser degree, the written representation of frontier cities would be dominated by Europeans. Within these confines, however, a set of generic conventions emerged within the United States, concerned primarily with arguing about whether the development of an urban frontier would help or harm the republic.

Describing frontiers in print—especially in visual form—proved extraordinarily difficult. The United States possessed a printing industry that amazed observers on both sides of the Atlantic. Yet much of that production was limited to political pamphlets, newspapers, religious tracts, and laws.5 And those printers rarely turned their attention to book-length studies of the West or of frontier cities. Meanwhile, the United States had only a small cadre of engravers and publishers trained in the highly exacting work of cartographic publication.6

As a result, Americans eagerly consumed geographic information, but most of the published representation of North American frontiers remained the work of Europeans, whether they were travelers, authors, or cartographers. Those books and maps established many of the objectives and measures of accuracy that shaped how Americans would go about describing frontier cities. After centuries in which European maps and travel narratives were most notable for the outlandishness of their claims or the inaccuracy of their details, during the eighteenth century a variety of factors—Enlightenment science, commercial interests, and the growth of travel literature as a popular genre—reshaped how Europeans represented North America. While the Spanish continued to treat geographic information as state secrets, French, British, and German publishers produced a growing number of books and maps that described frontier cities throughout the Americas. These objects continued a tradition of making expansive territorial claims for European empires, but they did so with growing technical expertise. This hardly means that Europeans had a clear picture of the North American West. To the contrary, the European image of North America was still shaped as much by ignorance as it was by knowledge. But the technical capacity to create a published representation of that landscape had grown considerably.7

In addition to maps, European publishers also produced other forms of illustration—local vistas, street scenes, historic events—that the United States simply could not match. Indeed, when it came to representing frontier cities, the United States produced almost none of these objects during the early republic. Instead, Americans would represent frontier cities in visual form almost exclusively through maps, and a small number of them.

Americans were quick to acknowledge this state of affairs. When policymakers sought to determine national boundaries or to set western policy, they looked to European sources. And as Americans began to publish their own accounts of frontier cities, they began by drawing on information first published in Europe.8

In sharp contrast to these European developments, representing frontier cities in the United States became the province of a small number of Americans, their work reflecting specific strengths in regional publishing. Rather than break new aesthetic ground, this cohort sought to emulate Europeans even as they sought to displace them. The editors, mapmakers, printers, and booksellers (occasionally one and the same) who proved so crucial to shaping the written and visual image of frontiers were primarily located in the cities of the Northeast. Philadelphia—which possessed both a robust publishing community and a cohort of cartographic engravers—produced the most important maps of the West. Meanwhile, of all places it was New England, particularly Boston, that produced some of the most important and abundant written descriptions of frontier cities. Although the regional culture of New England was perhaps the farthest removed from frontier concerns, New England publishers were the largest producers of educational materials, and many of the first representations of frontier cities were in reference books and school texts as well as the early travel narratives that rolled off New England presses.9

The impact of Philadelphia and New England is all the more striking in comparison to Virginia. After all, the Old Dominion played a far greater role in populating and governing the West, producing not only many of the settlers who descended on the trans-Appalachian West during the early republic, but also most of the officials who assumed leadership in the territorial system. Yet for all this influence, the limited publishing capacity of Virginia and the near-absence of cartographic publishing guaranteed that Virginia would play almost no role in creating a published representation of frontier cities.

Yet this hardly means that Philadelphia and New England lacked a frame of reference for representing frontier cities. To the contrary, if frontiers were unfamiliar places to the publishing community, cities were not. The cities that produced books and maps, Philadelphia and Boston, were themselves the subjects of books and maps, as were other cities like Baltimore and Charleston. Printers had long reproduced books and maps that reinforced the central, conflicting tropes of urban description. Cities were at once centers of civilization and of corruption. American travelers took these tropes with them when they visited frontier cities, often reproducing them in their published accounts. But so, too, did authors and editors in Philadelphia or Boston. They brought those assumptions and experiences with them as they produced the first books and maps to describe frontier cities.

Within these highly specific technical and aesthetic confines, Americans struggled to represent the cities of North American frontiers. They did so primarily though a small number of books and maps. There was more at work here than some vague sense of cultural nationalism, a vital point in understanding the process of landscape representation in the early republic. A small number of Americans were arguing that the nation needed its own literary and artistic production in order to establish itself as an independent nation. But the people making those claims were—not surprisingly—men and women who defined themselves as writers and artists. The men who sought to represent western cities saw things differently. In an abstract sense, Americans were indeed attempting to claim North America through the creation of a domestic publishing industry that would describe the United States on the Americans’ terms. But in the print shops and bookstores of the United States, or on the desks and drafting tables of American writers and cartographers, the goals were more pragmatic. American printers hoped to displace their European competitors through direct market competition. The federal government was eager to see a domestic industry of landscape description that would help sustain American territorial pretensions.10

These were the technical and economic circumstances that shaped what the United States could produce. But as that cultural production got under way, just what sort of frontier cities emerged from these highly specific institutional and political circumstances? There was no simple answer, for Americans were divided in their conclusions about the cities in particular just as they were divided about frontiers in general.

In their efforts to create a printed and visual record of frontier cities, Americans seemed to approach the task with all the ethnic chauvinism and cultural baggage they could muster. But the portraits that emerged were always more than mere expressions of national, racial, or ethnic supremacy. To the contrary, the apparent uniformity of these describers (white, Anglo-American, generally well educated) collapsed as other factors shaped their work. The men who described frontier cities generally fell into the following five groups: boosters, geographers, cartographers, explorers, and travelers. Their descriptions of frontier cities emerged through this intersection of regional diversity, authorial objective, and generic conventions.

The boosters were among the most prolific describers of frontier cities, and for obvious reasons. Land speculators, aspiring town builders, and would-be local politicos all saw tremendous benefits in portraying every emerging hamlet as the Athens of the West. This had certainly been the case in European empires throughout the Western Hemisphere, and it was a tradition that Americans joined with a vengeance. The boosters were particularly eager to promote places like Pittsburgh, Chillicothe, Lexington, and Nashville. They were less concerned with the trans-Mississippi West or the Great Lakes, let alone the Far West beyond, and for obvious reasons. First, many of the boosters were financially invested in converting new settlements into vibrant cities, and few of them were connected to any projects west of the Mississippi. Second, the boosters sought to celebrate the capacity of the United States to replace savagery with civilization, and they were hardly willing to acknowledge that Europeans could achieve the same goal.

The Americans were not the first to do so, and they would not be the last. Boosterism—and its close relative, hucksterism—would be a mainstay in western history. Meanwhile, European imperial projects in other parts of the world generated a similar paper trail, characterized by similarly exaggerated enthusiasm.11

The boosters proclaimed that these places were, indeed, cities. But what made them cities? Demography alone did not do the job. Instead, it was the combination of population density, economic development, a built environment of technical sophistication, and a cosmopolitan culture that created a frontier city. The surrounding landscape was always fertile, the region was always ripe for further development and profitable investment. Perhaps most important, these were fundamentally civil and civilized settlements. Unlike the rural farms and villages that characterized (and in some ways still characterize) frontiers, these new frontier cities were important civilizing forces. They were the homes of schools, banks, courts, and other institutions of civilized society. Yet if these cities formed a civilizing bulwark against the un-civilizing landscape that surrounded them, as new cities far removed from the emerging metropoles of the Atlantic seaboard, frontier cities would be civil and virtuous. They could be the centers of commerce, development, and social connections. They could promote the independence of individual farmers while offsetting the potential isolation that so many observers characterized with the frontier.

Consider the case of Zadok Cramer, a printer and bookseller in Pittsburgh. Cramer regularly published a book called The Navigator. Part travel guide, part showpiece of western development, and always revenue-producer for Cramer, The Navigator invoked the boosters’ techniques for celebrating frontier cities as part of a larger effort to attract settlers to the West. In the 1802 edition, for example, Cramer wrote that “the local situation of this town is so very commanding, that it has been called the Key to the Western Country.” He was referring directly to Pittsburgh’s relationship to the surrounding rivers, but he was also imagining a future as a regional metropole. He described “near 400 dwelling houses, many of them large and elegantly built with brick; and about 2000 inhabitants.”12 He may have favored Pittsburgh, but he had similar compliments for Cincinnati, Louisville, and other emerging river cities of the Ohio Valley. That attitude was particularly clear in Cramer’s comment on Marietta. The first major settlement established by the early boosters and speculators of the Northwest Territory, Marietta was soon overshadowed by the other frontier cities of the Ohio Valley. To Cramer, however, this was a story of growth. “The progress of this town and the adjacent settlement was, for several years much impeded by Indian wars; but now bids fair to become a place of considerable importance. . . . The inhabitants of Marietta are among the first who have exported the produce of the Ohio country, in vessels of their own building.”13

Cramer produced new guides in the years that followed, in the process chronicling the emergence, growth, and in some cases the decline of aspiring frontier cities. Regardless of the fate of any one city, however, Cramer’s message was the same. The construction of frontier cities marked an unstoppable, civilizing development of the trans-Appalachian frontier.14

Cramer’s work also exemplified the degree to which describing frontier cities during the late eighteenth century was primarily achieved through words rather than pictures. Most immigrant guides, including Cramer’s, generally eschewed illustration. What visual material they did include usually consisted of local river surveys.15 Although Cramer published in the nineteenth century, his work was very much that of the eighteenth century, when the United States possessed only limited capacity for illustrated publishing. This remained the case for Cramer in no small part because he operated from Pittsburgh. Living in a frontier city that possessed only the most basic publishing capacity, Cramer was incapable of visualizing frontier cities. Nor was Pittsburgh unique. Throughout the earlier republic, frontier cities could not describe themselves.

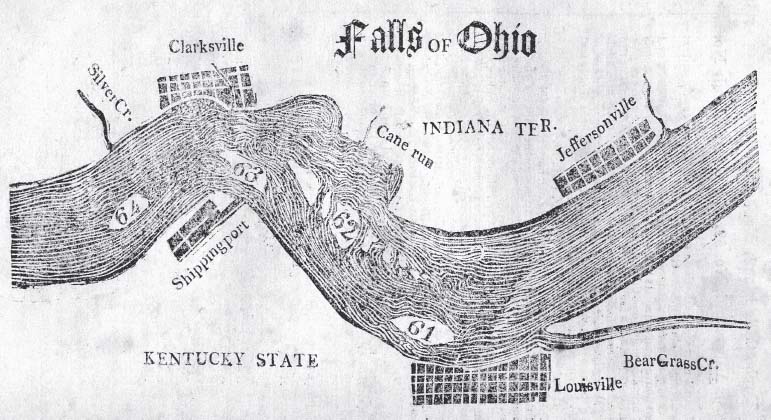

Figure 9.1. Map of the Ohio River and towns. Zadok Cramer, The Navigator: Containing Directions for Navigating the Monongahela, Alleghany, Ohio, and Mississippi Rivers (Pittsburgh: printed and published by Cramer, Spear, & Eichbaum, 1814), 124. Courtesy St. Louis Mercantile Library Association of the University of Missouri–St. Louis.

If the boosters were going to describe frontier cities, they would need to do so through the publishing capacity in cities that, appropriately rather than ironically, definitely were not on frontiers. One of the first men to conclude there might be real value to a visual representation of frontier cities was John Filson. An avid speculator in and relentless booster of Kentucky, his 1784 Discovery, Settlement and Present State of Kentucke became a landmark in American natural history and environmental writing.16 It was also a landmark in cartographic publishing, for Filson separately commissioned an engraver named Henry Pursell to produce a map. Pursell’s work was quite literally a road map for the kind of settlers that Filson hoped to attract with his book. It showed routes that connected the emerging settlements of Kentucky to the population centers of neighboring states, especially Virginia. Filson’s account of emerging civil communities took visual form in the towns of Lexington and Louisville, which appear as diversified settlements connected to the larger world by roads heading in all directions.17

The map that Filson commissioned did more than describe Kentucky. It constituted one of the first attempts within the United States to create a mass-produced visual representation situating frontier cities within a broader West. But Filson used these new technical capacities to advance an old idea in boosterism. He described frontier cities as the font of energy, prosperity, and civilization.

Throughout these years, published local maps that went beyond the general representation of Cramer or Filson were still few and far between. This remained the case in the United States even as the trade in urban maps produced in Europe continued. In the process, those European maps implicitly announced which cities mattered. By 1776, for example, emerging frontier cities like New Orleans and Montreal were already the subject of numerous well-distributed published maps. Consider Jacques Nicolas Bellin’s 1764 map of New Orleans (figure 9.3). Only a few years earlier, the Crescent City had been a struggling settlement, the center of a colony that both France and Spain considered strategically valuable but economically unsuccessful.18 In Bellin’s visual description, however, New Orleans was a solid, well-planned community.

Maps produced into the nineteenth century announced the growth of places like New Orleans or Montreal which might be located in intercultural contact zones but which, from the perspective of urban design, looked little different from cities that were located far way from anything that would be called a “frontier.”19 The genre itself contributed to this process. The standard conventions of urban maps had a tendency to make any settlement appear larger, more complex, and more thoroughly planned than an actual visit might suggest.

Figure 9.2. Map of Lexington and surrounding area. From John Filson, This Map of Kentucke . . . (Philadelphia: H. D. Pursell, 1784). Geography and Map Division, Library of Congress

Figure 9.3. Jacques Nicolas Bellin, Plan de la Nouvelle Orleans (Paris, 1764). Geography and Map Division, Library of Congress.

Americans struggled against the limitations of their own publishing capacities to produce similar descriptions of their own frontier cities, or any cities for that matter. Political circumstances and publishing developments overlapped to make this sort of representation both timely and possible. During the 1790s and early 1800s the federal government sought to consolidate its hold over frontier cities like Vincennes, Detroit, and Natchez. In 1803, the Louisiana Purchase extended federal boundaries to encompass the two most important frontier cities of the Mississippi Valley: New Orleans and St. Louis. Meanwhile, a new cohort of engravers trained in the cartographer’s art and a new cadre of geographic publishers combined to produce a slew of maps and books that sought to describe the United States even as the nation underwent geographic transformation. This development in publishing actually lagged well behind territorial expansion. It was only in the 1810s and 1820s that Americans began to represent these cities on a greater scale and with greater precision.20

For example, it was over a half-century after Bellin’s map of New Orleans, and almost a decade after the United States acquired New Orleans through the Louisiana Purchase, before Americans produced a major map of New Orleans. In 1817, New York and New Orleans printers, Charles Del Veccio and P. Maspero, respectively, produced what would eventually become one of the most widely circulating maps of early New Orleans (figure 9.4). Plan of the City and Suburbs of New Orleans did more than portray New Orleans as a growing city. The map quite literally surrounded the city with a set of sophisticated institutions: government buildings, theaters, and a publicly funded school.

Figure 9.4. I. Tanesse and William Rollinson, Plan of the City and Suburbs of New Orleans: from an actual survey made in 1815 (New York and New Orleans: Charles Del Vecchio, P. Maspero, 1817). Geography and Map Division, Library of Congress.

Figure 9.5. Bank of St. Louis, $10 denomination (detail), March 1817. Eric P. Newman Numismatic Education Society.

St. Louis underwent a similar staggered introduction in print and visual culture. St. Louis was the subject of written description, but it would be years before the struggling frontier outpost generated the published maps that would announce it as a city.

One of the first examples came from 1817, and it took the form not of a map or a book illustration but rather something as seemingly simple as a ten-dollar bill. Issued by the Bank of St. Louis, the currency note included a small representation of the waterfront development. St. Louis emerges as the site of diversified construction—large and small buildings, French-designed homes and neoclassical structures—and a busy waterfront. That this was on a bank note was no small affair, for all frontier cities hoped to establish their credentials as cities by demonstrating a strong financial infrastructure. Even the medium of the bank note—an engraving on paper—stood as a reminder of the importance of the physical medium of representing cities. After decades in which the paucity of engravers made frontier cities incapable of representing themselves visually, something as simple as a banknote was an announcement that frontier cities could describe themselves in both words and pictures.

Figure 9.6. The St. Louis waterfront. From E. Dupré, Atlas of the City and County of St. Louis, by Congressional Townships . . . (St. Louis: E. Dupré, 1838), frontispiece. St. Louis Imprints Collection, St. Louis Mercantile Library Association at the University of Missouri–St. Louis.

The first widely circulating maps of St. Louis only appeared in the 1820s. By 1838, St. Louis was finally producing the visual record to announce itself as a city. An atlas published that year showed local plots and listed landowners. It also included an illustration of the city’s waterfront, portraying the sort of bustling development, transportation, and commerce that came to define the image the city hoped to create for itself in the nineteenth century.

The growth in American publishing was equally dramatic in its representation of the cities of the trans-Appalachian West, and with much the same point. Maps of cities like Cincinnati, Louisville, and Lexington portrayed this sort of development in words and pictures. These maps showed well-planned cities growing quickly from their humble origins. But to what degree were these still cities on frontiers? The very creation of these visual representations suggested that these places were not the locations of give-and-take, of intercultural contact, or of ill-defined rules and power. In other words, these representations claimed that in becoming cities, these places had lost all the characteristics that historians now use to define a place as a frontier.21

Although these maps certainly had an implicitly celebratory quality to them, it is important to distinguish them from the more explicitly boosterish quality of work like John Filson’s. Filson certainly hoped to generate profits from their books, but that was only one facet of his efforts to profit from western development. Filson was a speculator first and writer second. In sharp contrast, the new generation of American cartographic publishers were, first and foremost, publishers. That their work dovetailed with that of the boosters created no problem for them, but they nonetheless belonged to a different cohort with different concerns.

Yet the work of publishers was hardly uniform in supporting the boosters’ claims. To the contrary, the expanding publishing capacity of the United States would play a crucial role in supporting the claims of another group that described frontier cities in far more ambivalent terms.

Even as boosters told a story of how places ceased to be frontiers, other describers and other texts told a different story altogether. Rather than redeem the republic, frontier cities might destroy civilization. Jedidiah Morse, the leading American geographer, established a pattern for describing frontier cities that his professional colleagues quickly emulated. Morse’s title as “geographer” can be deceiving. Morse and others like him were concerned not just with cartography and geographic measurement. Rather, many of them produced schoolbooks and general reference works that situated geography at the center of a broader educational project. They addressed topography and ecology, but above all they hoped to describe the political and demographic jurisdictions of the world.

Morse himself relied on boosterish western promoters like Filson, but he drew very different conclusions. Morse worried that weak civic institutions would decivilize western settlers. Yet if Morse implicitly celebrated cities (he had plenty of good things to say about Boston, Philadelphia, and New York), unlike Filson, he doubted the capacity of frontier cities to preserve a civilized culture.

Morse considered the western reserve of the United States “not only the most extensive, but by far the richest, and most valuable part of our country.” It had “the finest land in the world . . . [and] there is nothing in other parts of the globe, which resembles the prodigious chain of lakes in this part of the world.” But that very potential had the seeds of obvious problems for Morse. For now the West “remains in it original state, and lies buried in the midst of its own spontaneous luxuriousness.” For Morse, luxury was never a good thing. The great question for Morse—as indeed it was for Jefferson and Filson—was whether the West could develop an appropriate culture.22

Morse and Jefferson may seem confusing. They should, because their own work on frontier cities contained inherent and revealing contradictions. Jefferson sought to celebrate frontier towns as an example of western settlement, but his criticism of eastern cities threatened to undermine any celebration of their frontier counterparts. Conversely, Morse idealized the cities and towns of the Northeast, yet he was unable to apply that celebratory outlook to the towns and cities emerging in the West. The two men also could not have been more different politically. A New England Federalist, Morse was dismayed at Jefferson’s presidential victory in the election of 1800. Historians have tended to treat Morse accordingly, focusing primarily on his periodic political machinations and emphasizing his differences with the likes of Jefferson. But when it came to discussing frontier cities, both Morse and Jefferson contributed to a print culture that saw real dangers in urban development.

Understanding Morse and Jefferson is so important because they are not only emblematic of broader debates in politics and culture, but because they were particularly important in shaping the image of frontier cities. As a public figure, Jefferson repeatedly sought to shape the West. As a private individual, Morse’s publishing career established many of the standards for how writers and editors described the nation. Both men imported—and often conflated—their ideas about the West and about urban life into their efforts to make sense of frontier cities.

And it was the comments of men like Morse and Jefferson that got to the core of how Americans struggled to make sense of frontier cities through print and visual culture. Any attempt to represent those cities was never entirely an attempt to describe the frontier. The broader debate about cities inevitably affected, and occasionally threatened to consume, the discussion of frontiers. And in that reality lies the profound challenge for studies of frontier cities. The subject remains primarily the concern of frontier historians, but urban historians are the specialists who have most thoroughly theorized how Americans conceived of the city through culture. Once again, the realities of American publishing proved crucial. Neither Morse nor Jefferson actually lived in cities, but most American editors and publishers did.

Boosters and critics, publishers and cartographers, these Americans had all engaged in a debate about frontier cities that they often did not even know was occurring, but which nonetheless went on within the texts they produced. This debate among Americans had been under way for almost a generation before the critics received additional support in the reports from a diverse set of individual travelers: men and occasionally women who passed through the frontier regions that most geographers chose to avoid.

These travelers had their own concerns about frontier cities, yet if they shared the same tone of anxiety that marked some geographies, that tone emerged from very different roots.23 As a result, while Morse’s fears about the West might be rooted in the particular culture of the Northeast, this concern about the way that frontiers could decivilize even the most virtuous soul was common currency in western landscape description during the eighteenth century. The usual culprit was the general condition of frontier life. Weak institutions of civil society could not check the natural, baser human instincts. Meanwhile, Indians presented a seductive alternative with the promise of a carefree existence. White commentators concluded the same impulse could overcome white settlers. The West would quite literally take civilized Americans and transform them into uncivilized savages.24

Meanwhile, other detractors focused much of their scorn on the intercultural contact and interracial unions that abounded in the frontier cities of the French and Spanish empires. Texts produced in the United States mirrored the general attitude among whites, especially those in the East, who were committed to racial supremacy and racial separation. Many of those American texts also drew directly on claims first made by Europeans. For example, Estwick Evans’s concerns about New Orleans in 1819 bore considerable similarity to the comments of Jacques Pitot, a Frenchman who in 1802 published an account of his own travels through the North American frontiers. He described “a public ball, where those who have a bit of discretion prefer not to appear, organized by the free people of color, is each week the gathering place for the scum of such people and of those slaves who, eluding their owner’s surveillance, go there to bring their plunder.”25

While Pitot’s outrage might resonate with Anglo-Americans, Pitot operated from highly specific concerns. He blamed the corruption of the local urban population (whether Francophone white, Afro-Louisianian, or Native American) on a lax Spanish administration, as a part of a broader critique of Spanish imperial policy. Americans had their own reasons to decry the corruption of frontier cities like New Orleans, St. Louis, Montreal, and Santa Fe. Celebrations of rural independence in the United States had always used urban Europe as the foil. Meanwhile, Americans expressed their own anxieties about their own cities, fearing that the possibilities of the New World might be overwhelmed by the same urban decay that was consuming the Old World.

The result was a powerful critique of frontier cities that was constantly doing battle with the unchecked optimism of the boosters, speculators, and men like Jefferson who imagined the frontier might redeem the city. Nor were these comments limited to Europeans and New Englanders. Some of the first Americans to reach New Orleans and St. Louis, many of them committed expansionists or loyal Jeffersonians, shared Pitot’s conclusions. They, too, believed that frontier cities suffered from their proximity to the frontier. To this they added that all European imperial systems were fundamentally corrupt, and that corruption took root in the cities the Europeans had created on the frontiers of their American colonies.26

Even as the promoters, geographers, travelers, and cartographers struggled to find some way of conceptualizing frontier cities, the people whose work is most often associated with describing the frontier were strikingly absent from this discussion. Throughout the early republic, the federal government dispatched a variety of public officials to explore, survey, and report on the West. Most of those explorers produced major written works as well as maps. Missing from most of their discussion was any substantive discussion of the frontier cities that were of so much concern to other describers. This became the case in part for the obvious reason that these expeditions usually began where major white settlements ended. Yet other factors came into play. First and foremost was the assumption that it was not the task of the explorers to describe themselves or their world. Instead, most of them carried explicit instructions to focus their efforts on describing the unfamiliar, the exotic, the unknown. In fact, most of their expedition accounts began at the moment they left frontier cities to begin exploring points farther west. So while private travelers assumed that readers wanted to know about the European and Euro-American settlements in the West, federal explorers usually ignored them altogether.27

Of course, cities were exotic places, a fact which helps make sense of the particular cultural space in which people situated frontier cities. After all, the majority of people in North America at the turn of the nineteenth century lived in rural—not urban—settings. Similarly, travelers in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries always commented on the cosmopolitan exoticism of the cities of the Atlantic World. But for American explorers, frontier cities functioned within their published texts as the gateway from the familiar to the exotic. All the more striking is the fact that many of the men who led these expeditions had extended careers in federal employment that usually situated them in frontier cities.

Yet this hardly means explorers avoided frontier cities altogether. But their books and maps described places of dense population that few Euro-Americans would consider cities. Instead, the published texts of western exploration provided detailed accounts of the Indian metropoles of the North American West. The Lewis and Clark Expedition famously spent the winters of 1804–1805 and 1805–1806 in the center of large village groupings: the Mandan one year and the Clatsop the next. The 1819–1820 Yellowstone Expedition of Stephen Harriman Long resulted in a published narrative that offered its own accounts of dense Indian settlement among the Mandan. Meanwhile, the Freeman-Custis Expedition of 1806 concluded in a showdown with the Spanish among the Caddo villages of the Red River valley.28

The explorers did not use the word “city” to describe the centers of Indian population in the Far West, in large part because they did not think the word was appropriate to what they saw. Nonetheless, their words described places of dense population, complex social organization, and elaborate trade. Meanwhile, their maps quite literally put Indian settlement on the map, situating Indians by the thousands on the printed representation of the North American landscape. The mere existence of those maps was something of a revolution unto itself. All of them were produced in Philadelphia. During the 1810s and 1820s, when American explorers published their accounts, Philadelphia’s cartographic community was mass-producing stand-alone maps and multi-page atlases, displaying both technical skill and business savvy that had been almost entirely absent two decades before.

It took text and visual materials together to make these claims. The maps of the various western explorers located Indian cities on the landscape, but in a manner that was never so distinctive as the cities created by white settlers. It was left for the detailed text to describe the large populations, the complex social structures, the vigorous trade, and the permanent dwellings that made these Indian villages into places that whites might not call cities, but which they nonetheless acknowledged as metropoles of the frontier.

Scholars of mapmaking have long recognized that maps, like those by the American explorers, did more than describe the land. They were vital to the numerous European and Euro-American projects to claim the land as the property of individuals, companies, nations, or empires. Maps made these territorial claims in regional and continental terms, but they could also do so in local urban terms, albeit in varied, complex, and subtle ways. For example, maps could situate Indian settlements within national boundaries, but hardly as a way to announce Indian autonomy. The maps of American explorers did so as part of a broader effort to announce federal sovereignty in the West. Maps could also erase Indian frontier cities while proclaiming the growth of their Anglo-American counterparts, as Filson had done for Kentucky. These efforts constituted a direct counterpart to the 1838 atlas of St. Louis (figure 9.6). In the same way that the atlas sought to describe individual claims to property, other maps situated whole frontier cities within broader claims of ownership.

Dupré’s 1838 atlas marks an appropriate conclusion to this story, for it reinforces the ways in which cultural production, demographic change, and urban development overlapped to shape how Americans conceived of frontier cities. A series of profound demographic and cultural changes occurred on the frontiers of North America during the 1820s and ’30s. Early frontier settlements (St. Louis, Natchez, or Chicago) became more densely populated cities. Meanwhile, some of the earliest frontier cities were located in places that were no longer frontiers. New Orleans, Louisville, or Cincinnati may have undergone incremental change, but Louisiana, Kentucky, and Ohio no longer fit the criteria for “frontiers.” In addition to these changes for existing frontier cities, it was during the antebellum era that a host of new frontier cities came into being.

Yet no less important were the representational changes that corresponded with—but were never entirely caused by—these developments in demography and settlement. The profound changes in print and visual culture in that antebellum era kept pace with the profound changes at work on frontiers, combining to alter how Americans understood frontier cities in the decades that followed.

Understanding that process begins by considering two Americans who proved crucial to describing the frontiers of North America. After a half-century of situating frontier cities within a larger continental geography, Jedidiah Morse finally traveled to a frontier in 1820 on an extended tour with the nominal focus of reporting to a missionary society on the condition of Indians along the U.S.-Canadian border. He visited places like Detroit and Mackinac.29 Earlier that year, Henry Rowe Schoolcraft had passed through the same region on one of a series of western travels that resulted in major published narratives.30 Schoolcraft wrote that “Detroit occupies an eligible situation on the west banks of the strait that connects Lake Erie with Lake St. Clair. . . . The town consists of about two hundred and fifty houses, including public buildings,* and has a population of fourteen hundred and fifteen inhabitants, exclusive of the garrison.† It enjoys the advantages of a regular plan, spacious streets, and a handsome elevation of about forty feet above the river, of which it commands the finest views.” Schoolcraft explained that the old French style of architecture had given way to the norms of New York, adding that “an air of taste and neatness is thus thrown over the town, which superadded to its elevated situation, the appearances of an active and growing commerce, the bustle of mechanical business, its moral institutions,* and the local beauty of the site, strikes us with a feeling of surprise which is the more gratifying as it was not anticipated.” The asterisks pointed to written lists of public and private institutions similar to the buildings that appeared so proudly in the maps of frontier cities.31

In sharp contrast to Morse who had little to say about Detroit and Mackinaw, Schoolcraft considered Detroit a model for development. Of course, development had a particular meaning for Schoolcraft. He described the capital of the Michigan Territory as a budding metropolis, with a well-planned town replacing the older frontier exchange outpost. Schoolcraft later became an Indian agent and married a woman of Ojibwa and Irish-American ancestry. He considered himself fundamentally sympathetic to Indians. Nonetheless, Detroit’s possibilities as a city hinged on its capacity to replace Indian dominance with white planning.

Despite their differences, Morse and Schoolcraft had participated in a similar process of cultural production. Geographers, cartographic publishers, and the authors of immigrant guides did more than announce the existence of frontier cities. These men chronicled their development, creating a publication history of growth and conquest that was often more apparent than real. Equally important, this story emerged in large part from the economic needs of publishers. The dynamic changes in political geography during the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries proved crucial to the rate and profits of publication. The regular exchange of territorial claims (either through treaty or warfare), the forced removal of Indians, and the information from western explorers provided publishers with the ideal marketing rationale to explain why Americans should regularly purchase new editions of atlases they might already own. Frontier cities were part of this story as well. Some quite literally grew before a viewer’s eyes. For example, the typeface that publishers used to show emerging frontier cities of the Ohio River Valley went from small fonts often overshadowed by neighboring Indians to large fonts that commanded the landscape.

Morse and Schoolcraft completed their visits to Detroit on the eve of changes in American cultural production and publication that held the potential to transform the representation of frontier cities. Schoolcraft himself—unlike so many other Americans who described frontier cities—now occupies his own space alongside other contemporary literary figures such as James Fenimore Cooper, Nathaniel Hawthorne, and Washington Irving. All of these men sought to develop a national literary scene while promoting various forms of cultural nationalism. But we lump the men who had represented frontier cities into this cohort at our own peril. While many of them were, in fact, public officials committed to federal policy, few saw themselves as literary figures and few expressed any commitment to cultural nationalism.32

Not only were Americans producing more books than ever before, but in the 1820s and 1830s the American publishing industry began to produce maps that rivaled those of their European competitors. Once again, this was hardly an act of cultural nationalism, but rather a shift of technical capacity within a highly competitive market. Equally important, Americans produced illustrations that were both detailed and cost effective. These travel narratives, maps, and illustrations continued to describe frontier cities throughout the nineteenth century. Yet at the very moment of their fulfillment, these generic forms faced new competition from texts that would eventually displace them in an effort to locate frontier cities within the American imagination. Novels, landscape paintings, lithographic surveys, and other forms of published representation increasingly assumed the cultural space occupied by travel narratives and maps.33

Indeed, frontier cities were among the first subjects of this cultural production. When John Caspar Wild, the Swiss-born artist who became a pioneer in lithography, came to the United States, he chose American cities as one of his first subjects. His list of subjects included not only places like New York, Philadelphia, and Boston, but also Cincinnati and St. Louis, old frontier cities which, by the 1830s, quite literally looked very much the same as their eastern counterparts.34

But frontier cities were represented, imagined, and interpreted very differently in the antebellum era than they had been during the early republic. The cities themselves had changed. By the mid-nineteenth century, many of the old frontier cities—dominated by the interaction among Frenchmen, Spaniards, Indians, and people of mixed-race ancestry—had undergone a demographic transformation when Anglo-Americans became the majority. Meanwhile the towns that Anglo-Americans had built from scratch demonstrated that the United States could build its own frontier cities. Yet no less important were the media that described these places. The book-publishing industry and the penny press delivered an effusion of narratives, in sharp contrast to the first accounts published only a generation before. Meanwhile, engraved and lithographic urban scenes increased not only the quantity of visual representation, but forever transformed the quality of visual representation. Maps, of course, remained profoundly important in the ways Americans understood the West, but they mattered less for the representation of frontier cities. Urban street scenes of the type that Wild produced responded to very different generic conventions than maps. They told different stories. Most importantly, by removing frontier cities from the frontiers that surrounded those cities in maps, these new forms of representation could increasingly separate frontier cities from frontiers.

That process of broad cultural change was well under way when Alexis de Tocqueville visited the United States. Too often, however, Tocqueville receives primacy of place as the quintessential describer of North America. In the intervening decades separating that Frenchman from an earlier generation of French travelers, Americans had created their own corpus to describe the cities of North American frontiers. In their own efforts to lay claim to North America, those describers had sought to resolve the place of cities on the frontier. In the end, that proved an awkward pursuit, one that revealed how Americans represented not just frontiers, but their country at large.