The Complete Works of

DIOGENES LAËRTIUS

(fl. c. 3rd century AD)

Contents

LIVES OF THE EMINENT PHILOSOPHERS

© Delphi Classics 2015

Version 1

The Complete Works of

DIOGENES LAËRTIUS

By Delphi Classics, 2015

Complete Works of Diogenes Laertius

First published in the United Kingdom in 2015 by Delphi Classics.

© Delphi Classics, 2015.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of the publisher, nor be otherwise circulated in any form other than that in which it is published.

Delphi Classics

is an imprint of

Delphi Publishing Ltd

Hastings, East Sussex

United Kingdom

Contact: sales@delphiclassics.com

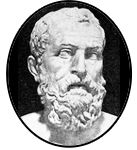

Ancient ruins in Caria — very little is known about the life of Diogenes Laërtius. Some historians believe his native town was Laerte in Caria.

![]()

Translated by R. D. Hicks

This biography of ancient Greek philosophers is believed to have been written by Diogenes Laërtius in the first half of the third century AD. Diogenes treats his subject in two divisions, which he divides between the Ionian and the Italian schools. The Ionian biographies begin with Anaximander and conclude with Clitomachus, Theophrastus and Chrysippus, while the Italian school commences with Pythagoras and culminates with Epicurus. The Socratic school, with its various branches, is classed with the Ionic; while the Eleatics and sceptics are treated under the Italian branch. Diogenes also includes his own poetic, though pedestrian, verse about the philosophers he discusses.

The compendium of biographies contains incidental remarks on many other philosophers and there are useful accounts concerning Hegesias, Anniceris, and Theodorus. Book VII is incomplete and breaks off during the life of Chrysippus. From a table of contents in one of the manuscripts (manuscript P), this book is known to have continued with Zeno of Tarsus, Diogenes, Apollodorus, Boethus, Mnesarchides, Mnasagoras, Nestor, Basilides, Dardanus, Antipater, Heraclides, Sosigenes, Panaetius, Hecato, Posidonius, Athenodorus, another Athenodorus, Antipater, Arius, and Cornutus. The whole of Book X is devoted to Epicurus, containing three long letters written by Epicurus, explaining the philosopher’s doctrines.

Diogenes’ chief authorities were Favorinus and Diocles of Magnesia, but his work also draws on books by Antisthenes of Rhodes, Alexander Polyhistor and Demetrius of Magnesia, as well as works by Hippobotus, Aristippus, Panaetius, Apollodorus of Athens, Sosicrates, Satyrus, Sotion, Neanthes, Hermippus, Antigonus, Heraclides, Hieronymus, and Pamphila.

Dionysiou monastery, codex 90 — a 13th-century manuscript containing Diogenes Laertius’ famous work

Thales of Miletus (c. 624 – c. 546 BC) was a pre-Socratic Greek philosopher from Miletus in Asia Minor and one of the Seven Sages of Greece. Aristotle regarded him as the first philosopher in the Greek tradition and he is the first to appear in Diogenes’ work.

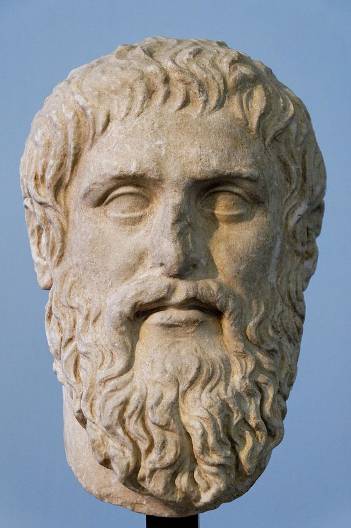

Plato (c. 428-c. 348 BC) is considered an essential figure in the development of philosophy, especially the Western tradition, and he founded the Academy in Athens, the first institution of higher learning in the Western world. Plato fills the entire third book of Diogenes’ ‘Lives and Opinions of Eminent Philosophers’.

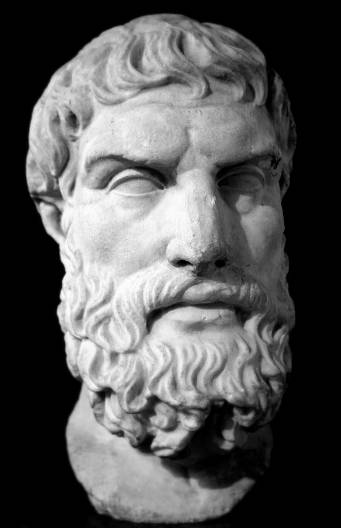

Epicurus (341–270 BC) was the founder of the school of Epicureanism. Only a few fragments and letters of Epicurus’ 300 written works remain. Much of what is known about Epicurean philosophy derives from later followers and commentators. Epicurus is last philosopher to appear in Diogenes’ ‘Lives and Opinions of Eminent Philosophers’.

1. There are some who say that the study of philosophy had its beginning among the barbarians. They urge that the Persians have had their Magi, the Babylonians or Assyrians their Chaldaeans, and the Indians their Gymnosophists; and among the Celts and Gauls there are the people called Druids or Holy Ones, for which they cite as authorities the Magicus of Aristotle and Sotion in the twenty-third book of his Succession of Philosophers . Also they say that Mochus was a Phoenician, Zamolxis a Thracian, and Atlas a Libyan.

If we may believe the Egyptians, Hephaestus was the son of the Nile, and with him philosophy began, priests and prophets being its chief exponents. 2. Hephaestus lived 48,863 years before Alexander of Macedon, and in the interval there occurred 373 solar and 832 lunar eclipses. The date of the Magians, beginning with Zoroaster the Persian, was 5000 years before the fall of Troy, as given by Hermodorus the Platonist in his work on mathematics; but Xanthus the Lydian reckons 6000 years from Zoroaster to the expedition of Xerxes, and after that event he places a long line of Magians in succession, bearing the names of Ostanas, Astrampsychos, Gobryas, and Pazatas, down to the conquest of Persia by Alexander.

3. These authors forget that the achievements which they attribute to the barbarians belong to the Greeks, with whom not merely philosophy but the human race itself began. For instance, Musaeus is claimed by Athens, Linus by Thebes. It is said that the former, the son of Eumolpus, was the first to compose a genealogy of the gods and to construct a sphere, and that he maintained that all things proceed from unity and are resolved again into unity. He died at Phalerum, and this is his epitaph:

Musaeus, to his sire Eumolpus dear,

In Phalerean soil lies buried here;

and the Eumolpidae at Athens get their name from the father of Musaeus.

4. Linus again was (so it is said) the son of Hermes and the Muse Urania. He composed a poem describing the creation of the world, the courses of the sun and moon, and the growth of animals and plants. His poem begins with the line:

Time was when all things grew up at once;

and this idea was borrowed by Anaxagoras when he declared that all things were originally together until Mind came and set them in order. Linus died in Euboea, slain by the arrow of Apollo, and this is his epitaph:

Here Theban Linus, whom Urania bore,

The fair-crowned Muse, sleeps on a foreign shore.

And thus it was from the Greeks that philosophy took its rise: its very name refuses to be translated into foreign speech.

5. But those who attribute its invention to barbarians bring forward Orpheus the Thracian, calling him a philosopher of whose antiquity there can be no doubt. Now, considering the sort of things he said about the gods, I hardly know whether he ought to be called a philosopher; for what are we to make of one who does not scruple to charge the gods with all human suffering, and even the foul crimes wrought by the tongue amongst a few of mankind? The story goes that he met his death at the hands of women; but according to the epitaph at Dium in Macedonia he was slain by a thunderbolt; it runs as follows:

Here have the Muses laid their minstrel true,

The Thracian Orpheus whom Jove’s thunder slew.

6. But the advocates of the theory that philosophy took its rise among the barbarians go on to explain the different forms it assumed in different countries. As to the Gymnosophists and Druids we are told that they uttered their philosophy in riddles, bidding men to reverence the gods, to abstain from wrongdoing, and to practise courage. That the Gymnosophists at all events despise even death itself is affirmed by Clitarchus in his twelfth book; he also says that the Chaldaeans apply themselves to astronomy and forecasting the future; while the Magi spend their time in the worship of the gods, in sacrifices and in prayers, implying that none but themselves have the ear of the gods. They propound their views concerning the being and origin of the gods, whom they hold to be fire, earth, and water; they condemn the use of images, and especially the error of attributing to the divinities difference of sex. 7. They hold discourse of justice, and deem it impious to practise cremation; but they see no impiety in marriage with a mother or daughter, as Sotion relates in his twenty-third book. Further, they practise divination and forecast the future, declaring that the gods appear to them in visible form. Moreover, they say that the air is full of shapes which stream forth like vapour and enter the eyes of keen-sighted seers. They prohibit personal ornament and the wearing of gold. Their dress is white, they make their bed on the ground, and their food is vegetables, cheese, and coarse bread; their staff is a reed and their custom is, so we are told, to stick it into the cheese and take up with it the part they eat.

8. With the art of magic they were wholly unacquainted, according to Aristotle in his Magicus and Dinon in the fifth book of his History Dinon tells us that the name Zoroaster, literally interpreted, means “star-worshipper”; and Hermodorus agrees with him in this. Aristotle in the first book of his dialogue On Philosophy declares that the Magi are more ancient than the Egyptians; and further, that they believe in two principles, the good spirit and the evil spirit, the one called Zeus or Oromasdes, the other Hades or Arimanius. This is confirmed by Hermippus in his first book about the Magi, Eudoxus in his Voyage round the World , and Theopompus in the eighth book of his Philippica . 9. The last-named author says that according to the Magi men will live in a future life and be immortal, and that the world will endure through their invocations. This is again confirmed by Eudemus of Rhodes. But Hecataeus relates that according to them the gods are subject to birth. Clearchus of Soli in his tract On Education further makes the Gymnosophists to be descended from the Magi; and some trace the Jews also to the same origin. Furthermore, those who have written about the Magi criticize Herodotus. They urge that Xerxes would never have cast javelins at the sun nor have let down fetters into the sea, since in the creed of the Magi sun and sea are gods. But that statues of the gods should be destroyed by Xerxes was natural enough.

10. The philosophy of the Egyptians is described as follows so far as relates to the gods and to justice. They say that matter was the first principle, next the four elements were derived from matter, and thus living things of every species were produced. The sun and the moon are gods bearing the names of Osiris and Isis respectively; they make use of the beetle, the dragon, the hawk, and other creatures as symbols of divinity, according to Manetho in his Epitome of Physical Doctrines , and Hecataeus in the first book of his work On the Egyptian Philosophy . They also set up statues and temples to these sacred animals because they do not know the true form of the deity. 11. They hold that the universe is created and perishable, and that it is spherical in shape. They say that the stars consist of fire, and that, according as the fire in them is mixed, so events happen upon earth; that the moon is eclipsed when it falls into the earth’s shadow; that the soul survives death and passes into other bodies; that rain is caused by change in the atmosphere; of all other phenomena they give physical explanations, as related by Hecataeus and Aristagoras. They also laid down laws on the subject of justice, which they ascribed to Hermes; and they deified those animals which are serviceable to man. They also claimed to have invented geometry, astronomy, and arithmetic. Thus much concerning the invention of philosophy.

12. But the first to use the term, and to call himself a philosopher or lover of wisdom, was Pythagoras; for, said he, no man is wise, but God alone. Heraclides of Pontus, in his De mortua , makes him say this at Sicyon in conversation with Leon, who was the prince of that city or of Phlius. All too quickly the study was called wisdom and its professor a sage, to denote his attainment of mental perfection; while the student who took it up was a philosopher or lover of wisdom. Sophists was another name for the wise men, and not only for philosophers but for the poets also. And so Cratinus when praising Homer and Hesiod in his Archilochi gives them the title of sophist.

13. The men who were commonly regarded as sages were the following: Thales, Solon, Periander, Cleobulus, Chilon, Bias, Pittacus. To these are added Anacharsis the Scythian, Myson of Chen, Pherecydes of Syros, Epimenides the Cretan; and by some even Pisistratus the tyrant. So much for the sages or wise men.

But philosophy, the pursuit of wisdom, has had a twofold origin; it started with Anaximander on the one hand, with Pythagoras on the other. The former was a pupil of Thales, Pythagoras was taught by Pherecydes. The one school was called Ionian, because Thales, a Milesian and therefore an Ionian, instructed Anaximander; the other school was called Italian from Pythagoras, who worked for the most part in Italy. 14. And the one school, that of Ionia, terminates with Clitomachus and Chrysippus and Theophrastus, that of Italy with Epicurus. The succession passes from Thales through Anaximander, Anaximenes, Anaxagoras, Archelaus, to Socrates, who introduced ethics or moral philosophy; from Socrates to his pupils the Socratics, and especially to Plato, the founder of the Old Academy; from Plato, through Speusippus and Xenocrates, the succession passes to Polemo, Crantor, and Crates, Arcesilaus, founder of the Middle Academy, Lacydes, founder of the New Academy, Carneades, and Clitomachus. This line brings us to Clitomachus.

15. There is another which ends with Chrysippus, that is to say by passing from Socrates to Antisthenes, then to Diogenes the Cynic, Crates of Thebes, Zeno of Citium, Cleanthes, Chrysippus. And yet again another ends with Theophrastus; thus from Plato it passes to Aristotle, and from Aristotle to Theophrastus. In this manner the school of Ionia comes to an end.

In the Italian school the order of succession is as follows: first Pherecydes, next Pythagoras, next his son Telauges, then Xenophanes, Parmenides, Zeno of Elea, Leucippus, Democritus, who had many pupils, in particular Nausiphanes [and Naucydes], who were teachers of Epicurus.

16. Philosophers may be divided into dogmatists and sceptics: all those who make assertions about things assuming that they can be known are dogmatists; while all who suspend their judgement on the ground that things are unknowable are sceptics. Again, some philosophers left writings behind them, while others wrote nothing at all, as was the case according to some authorities with Socrates, Stilpo, Philippus, Menedemus, Pyrrho, Theodorus, Carneades, Bryson; some add Pythagoras and Aristo of Chios, except that they wrote a few letters. Others wrote no more than one treatise each, as Melissus, Parmenides, Anaxagoras. Many works were written by Zeno, more by Xenophanes, more by Democritus, more by Aristotle, more by Epicurus, and still more by Chrysippus. 17. Some schools took their name from cities, as the Elians and the Megarians, the Eretrians and the Cyrenaics; others from localities, as the Academics and the Stoics; others from incidental circumstances, as the Peripatetics; others again from derisive nicknames, as the Cynics; others from their temperaments, as the Eudaemonists or Happiness School; others from a conceit they entertained, as Truth-lovers, Refutationists, and Reasoners from Analogy; others again from their teachers, as Socratics, Epicureans, and the like; some take the name of Physicists from their investigation of nature, others that of Moralists because they discuss morals; while those who are occupied with verbal jugglery are styled Dialecticians.

18. Philosophy has three parts, physics, ethics, and dialectic or logic. Physics is the part concerned with the universe and all that it contains; ethics that concerned with life and all that has to do with us; while the processes of reasoning employed by both form the processes of dialectic. Physics flourished down to the time of Archelaus; ethics, as we have said, started with Socrates; while dialectic goes as far back as Zeno of Elea. In ethics there have been ten schools: the Academic, the Cyrenaic, the Elian, the Megarian, the Cynic, the Eretrian, the Dialectic, the Peripatetic, the Stoic, and the Epicurean.

19. The founders of these schools were: of the Old Academy, Plato; of the Middle Academy, Arcesilaus; of the New Academy, Lacydes; of the Cyrenaic, Aristippus of Cyrene; of the Elian, Phaedo of Elis; of the Megarian, Euclides of Megara; of the Cynic, Antisthenes of Athens; of the Eretrian, Menedemus of Eretria; of the Dialectical school, Clitomachus of Carthage; of the Peripatetic, Aristotle of Stagira; of the Stoic, Zeno of Citium; while the Epicurean school took its name from Epicurus himself.

Hippobotus in his work On Philosophical Sects declares that there are nine sects or schools, and gives them in this order: (1) Megarian, (2) Eretrian, (3) Cyrenaic, (4) Epicurean, (5) Annicerean, (6) Theodorean, (7) Zenonian or Stoic, (8) Old Academic, (9) Peripatetic. He passes over the Cynic, Elian, and Dialectical schools; 20. for as to the Pyrrhonians, so indefinite are their conclusions that hardly any authorities allow them to be a sect; some allow their claim in certain respects, but not in others. It would seem, however, that they are a sect, for we use the term of those who in their attitude to appearance follow or seem to follow some principle; and on this ground we should be justified in calling the Sceptics a sect. But if we are to understand by “sect” a bias in favour of coherent positive doctrines, they could no longer be called a sect, for they have no positive doctrines. So much for the beginnings of philosophy, its subsequent developments, its various parts, and the number of the philosophic sects.

21. One word more: not long ago an Eclectic school was introduced by Potamo of Alexandria, who made a selection from the tenets of all the existing sects. As he himself states in his Elements of Philosophy , he takes as criteria of truth (1) that by which the judgement is formed, namely, the ruling principle of the soul; (2) the instrument used, for instance the most accurate perception. His universal principles are matter and the efficient cause, quality, and place; for that out of which and that by which a thing is made, as well as the quality with which and the place in which it is made, are principles. The end to which he refers all actions is life made perfect in all virtue, natural advantages of body and environment being indispensable to its attainment.

It remains to speak of the philosophers themselves, and in the first place of Thales.

22. Herodotus, Duris, and Democritus are agreed that Thales was the son of Examyas and Cleobulina, and belonged to the Thelidae who are Phoenicians, and among the noblest of the descendants of Cadmus and Agenor. As Plato testifies, he was one of the Seven Sages. He was the first to receive the name of Sage, in the archonship of Damasias at Athens, when the term was applied to all the Seven Sages, as Demetrius of Phalerum mentions in his List of Archons . He was admitted to citizenship at Miletus when he came to that town along with Nileos, who had been expelled from Phoenicia. Most writers, however, represent him as a genuine Milesian and of a distinguished family.

23. After engaging in politics he became a student of nature. According to some he left nothing in writing; for the Nautical Astronomy attributed to him is said to be by Phocus of Samos. Callimachus knows him as the discoverer of the Ursa Minor; for he says in his Iambics :

Who first of men the course made plain

Of those small stars we call the Wain,

Whereby Phoenicians sail the main.

But according to others he wrote nothing but two treatises, one On the Solstice and one On the Equinox , regarding all other matters as incognizable. He seems by some accounts to have been the first to study astronomy, the first to predict eclipses of the sun and to fix the solstices; so Eudemus in his History of Astronomy . It was this which gained for him the admiration of Xenophanes and Herodotus and the notice of Heraclitus and Democritus.

24. And some, including Choerilus the poet, declare that he was the first to maintain the immortality of the soul. He was the first to determine the sun’s course from solstice to solstice, and according to some the first to declare the size of the sun to be one seven hundred and twentieth part of the solar circle, and the size of the moon to be the same fraction of the lunar circle. He was the first to give the last day of the month the name of Thirtieth, and the first, some say, to discuss physical problems.

Aristotle and Hippias affirm that, arguing from the magnet and from amber, he attributed a soul or life even to inanimate objects. Pamphila states that, having learnt geometry from the Egyptians, he was the first to inscribe a right-angled triangle in a circle, whereupon he sacrificed an ox. Others tell this tale of Pythagoras, amongst them Apollodorus the arithmetician. 25. (It was Pythagoras who developed to their furthest extent the discoveries attributed by Callimachus in his Iambics to Euphorbus the Phrygian, I mean “scalene triangles” and whatever else has to do with theoretical geometry.)

Thales is also credited with having given excellent advice on political matters. For instance, when Croesus sent to Miletus offering terms of alliance, he frustrated the plan; and this proved the salvation of the city when Cyrus obtained the victory. Heraclides makes Thales himself say that he had always lived in solitude as a private individual and kept aloof from State affairs. Some authorities say that he married and had a son Cybisthus; 26. others that he remained unmarried and adopted his sister’s son, and that when he was asked why he had no children of his own he replied “because he loved children.” The story is told that, when his mother tried to foroe him to marry, he replied it was too soon, and when she pressed him again later in life, he replied that it was too late. Hieronymus of Rhodes in the second book of his Scattered Notes relates that, in order to show how easy it is to grow rich, Thales, foreseeing that it would be a good season for olives, rented all the oil-mills and thus amassed a fortune.

27. His doctrine was that water is the universal primary substance, and that the world is animate and full of divinities. He is said to have discovered the seasons of the year and divided it into 365 days.

He had no instructor, except that he went to Egypt and spent some time with the priests there. Hieronymus informs us that he measured the height of the pyramids by the shadow they cast, taking the observation at the hour when our shadow is of the same length as ourselves. He lived, as Minyas relates, with Thrasybulus, the tyrant of Miletus.

The well-known story of the tripod found by the fishermen and sent by the people of Miletus to all the Wise Men in succession runs as follows. 28. Certain Ionian youths having purchased of the Milesian fishermen their catch of fish, a dispute arose over the tripod which had formed part of the catch. Finally the Milesians referred the question to Delphi, and the god gave an oracle in this form:

Who shall possess the tripod? Thus replies

Apollo: “Whosoever is most wise.”

Accordingly they give it to Thales, and he to another, and so on till it comes to Solon, who, with the remark that the god was the most wise, sent it off to Delphi. Callimachus in his Iambics has a different version of the story, which he took from Maeandrius of Miletus. It is that Bathycles, an Arcadian, left at his death a bowl with the solemn injunction that it “should be given to him who had done most good by his wisdom.” So it was given to Thales, went the round of all the sages, and came back to Thales again. 29. And he sent it to Apollo at Didyma, with this dedication, according to Callimachus:

Lord of the folk of Neleus’ line,

Thales, of Greeks adjudged most wise,

Brings to thy Didymaean shrine

His offering, a twice-won prize.

But the prose inscription is:

Thales the Milesian, son of Examyas [dedicates this] to Delphinian Apollo after twice winning the prize from all the Greeks.

The bowl was carried from place to place by the son of Bathycles, whose name was Thyrion, so it is stated by Eleusis in his work On Achilles , and Alexo the Myndian in the ninth book of his Legends .

But Eudoxus of Cnidos and Euanthes of Miletus agree that a certain man who was a friend of Croesus received from the king a golden goblet in order to bestow it upon the wisest of the Greeks; this man gave it to Thales, and from him it passed to others and so to Chilon.

30. Chilon laid the question “Who is a wiser man than I?” before the Pythian Apollo, and the god replied “Myson.” Of him we shall have more to say presently. (In the list of the Seven Sages given by Eudoxus, Myson takes the place of Cleobulus; Plato also includes him by omitting Periander.) The answer of the oracle respecting him was as follows:

Myson of Chen in Oeta; this is he

Who for wiseheartedness surpasseth thee;

and it was given in reply to a question put by Anacharsis. Daimachus the Platonist and Clearchus allege that a bowl was sent by Croesus to Pittacus and began the round of the Wise Men from him.

The story told by Andron in his work on The Tripod is that the Argives offered a tripod as a prize of virtue to the wisest of the Greeks; Aristodemus of Sparta was adjudged the winner but retired in favour of Chilon. 31. Aristodemus is mentioned by Alcaeus thus:

Surely no witless word was this of the Spartan, I deem,

“Wealth is the worth of a man; and poverty void of esteem.”

Some relate that a vessel with its freight was sent by Periander to Thrasybulus, tyrant of Miletus, and that, when it was wrecked in Coan waters, the tripod was afterwards found by certain fishermen. However, Phanodicus declares it to have been found in Athenian waters and thence brought to Athens. An assembly was held and it was sent to Bias; 32. for what reason shall be explained in the life of Bias.

There is yet another version, that it was the work of Hephaestus presented by the god to Pelops on his marriage. Thence it passed to Menelaus and was carried off by Paris along with Helen and was thrown by her into the Coan sea, for she said it would be a cause of strife. In process of time certain people of Lebedus, having purchased a catch of fish thereabouts, obtained possession of the tripod, and, quarrelling with the fishermen about it, put in to Cos, and, when they could not settle the dispute, reported the fact to Miletus, their mother-city. The Milesians, when their embassies were disregarded, made war upon Cos; many fell on both sides, and an oracle pronounced that the tripod should be given to the wisest; both parties to the dispute agreed upon Thales. After it had gone the round of the sages, Thales dedicated it to Apollo of Didyma. 33. The oracle which the Coans received was on this wise:

Hephaestus cast the tripod in the sea;

Until it quit the city there will be

No end to strife, until it reach the seer

Whose wisdom makes past, present, future clear.

That of the Milesians beginning “Who shall possess the tripod?” has been quoted above. So much for this version of the story.

Hermippus in his Lives refers to Thales the story which is told by some of Socrates, namely, that he used to say there were three blessings for which he was grateful to Fortune: “first, that I was born a human being and not one of the brutes; next, that I was born a man and not a woman; thirdly, a Greek and not a barbarian.” 34. It is said that once, when he was taken out of doors by an old woman in order that he might observe the stars, he fell into a ditch, and his cry for help drew from the old woman the retort, “How can you expect to know all about the heavens, Thales, when you cannot even see what is just before your feet?” Timon too knows him as an astronomer, and praises him in the Silli where he says:

Thales among the Seven the sage astronomer.

His writings are said by Lobon of Argos to have run to some two hundred lines. His statue is said to bear this inscription:

Pride of Miletus and Ionian lands,

Wisest astronomer, here Thales stands.

35. Of songs still sung these verses belong to him:

Many words do not declare an understanding heart.

Seek one sole wisdom.

Choose one sole good.

For thou wilt check the tongues of chatterers prating without end.

Here too are certain current apophthegms assigned to him:

Of all things that are, the most ancient is God, for he is uncreated.

The most beautiful is the universe, for it is God’s workmanship.

The greatest is space, for it holds all things.

The swiftest is mind, for it speeds everywhere.

The strongest, necessity, for it masters all.

The wisest, time, for it brings everything to light.

He held there was no difference between life and death. “Why then,” said one, “do you not die?” “Because,” said he, “there is no difference.” 36. To the question which is older, day or night, he replied: “Night is the older by one day.” Some one asked him whether a man could hide an evil deed from the gods: “No,” he replied, “nor yet an evil thought.” To the adulterer who inquired if he should deny the charge upon oath he replied that perjury was no worse than adultery. Being asked what is difficult, he replied, “To know oneself.” “What is easy?” “To give advice to another.” “What is most pleasant?” “Success.” “What is the divine?” “That which has neither beginning nor end.” To the question what was the strangest thing he had ever seen, his answer was, “An aged tyrant.” “How can one best bear adversity?” “If he should see his enemies in worse plight.” “How shall we lead the best and most righteous life?” “By refraining from doing what we blame in others.” 37. “What man is happy?” “He who has a healthy body, a resourceful mind and a docile nature.” He tells us to remember friends, whether present or absent; not to pride ourselves upon outward appearance, but to study to be beautiful in character. “Shun ill-gotten gains,” he says. “Let not idle words prejudice thee against those who have shared thy confidence.” “Whatever provision thou hast made for thy parents, the same must thou expect from thy children.” He explained the overflow of the Nile as due to the etesian winds which, blowing in the contrary direction, drove the waters upstream.

Apollodorus in his Chronology places his birth in the first year of the 35th Olympiad. 38. He died at the age of 78 (or, according to Sosicrates, of 90 years); for he died in the 58th Olympiad, being contemporary with Croesus, whom he undertook to take across the Halys without building a bridge, by diverting the river.

There have lived five other men who bore the name of Thales, as enumerated by Demetrius of Magnesia in his Dictionary of Men of the Same Name:

1. A rhetorician of Callatia, with an affected style.

2. A painter of Sicyon, of great gifts.

3. A contemporary of Hesiod, Homer and Lycurgus, in very early times.

4. A person mentioned by Duris in his work On Painting .

5. An obscure person in more recent times who is mentioned by Dionysius in his Critical Writings .

39. Thales the Sage died as he was watching an athletic contest from heat, thirst, and the weakness incident to advanced age. And the inscription on his tomb is:

Here in a narrow tomb great Thales lies;

Yet his renown for wisdom reached the skies.

I may also cite one of my own, from my first book, Epigrams in Various Metres :

As Thales watched the games one festal day

The fierce sun smote him, and he passed away;

Zeus, thou didst well to raise him; his dim eyes

Could not from earth behold the starry skies.

40. To him belongs the proverb “Know thyself,” which Antisthenes in his Successions of Philosophers attributes to Phemonoë, though admitting that it was appropriated by Chilon.

This seems the proper place for a general notice of the Seven Sages, of whom we have such accounts as the following. Damon of Cyrene in his History of the Philosophers carps at all sages, but especially the Seven. Anaximenes remarks that they all applied themselves to poetry; Dicaearchus that they were neither sages nor philosophers, but merely shrewd men with a turn for legislation. Archetimus of Syracuse describes their meeting at the court of Cypselus, on which occasion he himself happened to be present; for which Ephorus substitutes a meeting without Thales at the court of Croesus. Some make them meet at the Pan-Ionian festival, at Corinth, and at Delphi. 41. Their utterances are variously reported, and are attributed now to one now to the other, for instance the following:

Chilon of Lacedaemon’s words are true:

Nothing too much; good comes from measure due.

Nor is there any agreement how the number is made up; for Maeandrius, in place of Cleobulus and Myson, includes Leophantus, son of Gorgiadas, of Lebedus or Ephesus, and Epimenides the Cretan in the list; Plato in his Protagoras admits Myson and leaves out Periander; Ephorus substitutes Anacharsis for Myson; others add Pythagoras to the Seven. Dicaearchus hands down four names fully recognized: Thales, Bias, Pittacus and Solon; and appends the names of six others, from whom he selects three: Aristodemus, Pamphylus, Chilon the Lacedaemonian, Cleobulus, Anacharsis, Periander. Others add Acusilaus, son of Cabas or Scabras, of Argos. 42. Hermippus in his work On the Sages reckons seventeen, from which number different people make different selections of seven. They are: Solon, Thales, Pittacus, Bias, Chilon, Myson, Cleobulus, Periander, Anacharsis, Acusilaus, Epimenides, Leophantus, Pherecydes, Aristodemus, Pythagoras, Lasos, son of Charmantides or Sisymbrinus, or, according to Aristoxenus, of Chabrinus, born at Hermione, Anaxagoras. Hippobotus in his List of Philosophers enumerates: Orpheus, Linus, Solon, Periander, Anacharsis, Cleobulus, Myson, Thales, Bias, Pittacus, Epicharmus, Pythagoras.

Here follow the extant letters of Thales.

Thales to Pherecydes

43. “I hear that you intend to be the first Ionian to expound theology to the Greeks. And perhaps it was a wise decision to make the book common property without taking advice, instead of entrusting it to any particular persons whatsoever, a course which has no advantages. However, if it would give you any pleasure, I am quite willing to discuss the subject of your book with you; and if you bid me come to Syros I will do so. For surely Solon of Athens and I would scarcely be sane if, after having sailed to Crete to pursue our inquiries there, and to Egypt to confer with the priests and astronomers, we hesitated to come to you. For Solon too will come, with your permission. 44. You, however, are so fond of home that you seldom visit Ionia and have no longing to see strangers, but, as I hope, apply yourself to one thing, namely writing, while we, who never write anything, travel all over Hellas and Asia.”

Thales to Solon

“If you leave Athens, it seems to me that you could most conveniently set up your abode at Miletus, which is an Athenian colony; for there you incur no risk. If you are vexed at the thought that we are governed by a tyrant, hating as you do all absolute rulers, you would at least enjoy the society of your friends. Bias wrote inviting you to Priene; and if you prefer the town of Priene for a residence, I myself will come and live with you.”

45. Solon, the son of Execestides, was born at Salamis. His first achievement was the σεισάχθεια or Law of Release, which he introduced at Athens; its effect was to ransom persons and property. For men used to borrow money on personal security, and many were forced from poverty to become serfs or daylabourers. He then first renounced his claim to a debt of seven talents due to his father, and encouraged others to follow his example. This law of his was called σεισάχθεια, and the reason is obvious.

He next went on to frame the rest of his laws, which would take time to enumerate, and inscribed them on the revolving pillars.

46. His greatest service was this: Megara and Athens laid rival claims to his birthplace Salamis, and after many defeats the Athenians passed a decree punishing with death any man who should propose a renewal of the Salaminian war. Solon, feigning madness, rushed into the Agora with a garland on his head; there he had his poem on Salamis read to the Athenians by the herald and roused them to fury. They renewed the war with the Megarians and, thanks to Solon, were victorious. 47. These were the lines which did more than anything else to inflame the Athenians:

Would I were citizen of some mean isle

Far in the Sporades! For men shall smile

And mock me for Athenian: “Who is this?”

“An Attic slave who gave up Salamis”;

and

Then let us fight for Salamis and fair fame,

Win the beloved isle, and purge our shame!

He also persuaded the Athenians to acquire the Thracian Chersonese. 48. And lest it should be thought that he had acquired Salamis by force only and not of right, he opened certain graves and showed that the dead were buried with their faces to the east, as was the custom of burial among the Athenians; further, that the tombs themselves faced the east, and that the inscriptions graven upon them named the deceased by their demes, which is a style peculiar to Athens. Some authors assert that in Homer’s catalogue of the ships after the line:

Ajax twelve ships from Salamis commands,

Solon inserted one of his own:

And fixed their station next the Athenian bands.

49. Thereafter the people looked up to him, and would gladly have had him rule them as tyrant; he refused, and, early perceiving the designs of his kinsman Pisistratus (so we are told by Sosicrates), did his best to hinder them. He rushed into the Assembly armed with spear and shield, warned them of the designs of Pisistratus, and not only so, but declared his willingness to render assistance, in these words: “Men of Athens, I am wiser than some of you and more courageous than others: wiser than those who fail to understand the plot of Pisistratus, more courageous than those who, though they see through it, keep silence through fear.” And the members of the council, who were of Pisistratus’ party, declared that he was mad: which made him say the lines:

A little while, and the event will show

To all the world if I be mad or no.

50. That he foresaw the tyranny of Pisistratus is proved by a passage from a poem of his:

On splendid lightning thunder follows straight,

Clouds the soft snow and flashing hail-stones bring;

So from proud men comes ruin, and their state

Falls unaware to slavery and a king.

When Pisistratus was already established, Solon, unable to move the people, piled his arms in front of the generals’ quarters, and exclaimed, “My country, I have served thee with my word and sword!” Thereupon he sailed to Egypt and to Cyprus, and thence proceeded to the court of Croesus. There Croesus put the question, “Whom do you consider happy?” and Solon replied, “Tellus of Athens, and Cleobis and Biton,” and went on in words too familiar to be quoted here.

51. There is a story that Croesus in magnificent array sat himself down on his throne and asked Solon if he had ever seen anything more beautiful. “Yes,” was the reply, “cocks and pheasants and peacocks; for they shine in nature’s colours, which are ten thousand times more beautiful.” After leaving that place he lived in Cilicia and founded a city which he called Soli after his own name. In it he settled some few Athenians, who in process of time corrupted the purity of Attic and were said to “solecize.” Note that the people of this town are called Solenses, the people of Soli in Cyprus Solii. When he learnt that Pisistratus was by this time tyrant, he wrote to the Athenians on this wise:

52. If ye have suffered sadly through your own wickedness, lay not the blame for this upon the gods. For it is you yourselves who gave pledges to your foes and made them great; this is why you bear the brand of slavery. Every one of you treadeth in the footsteps of the fox, yet in the mass ye have little sense. Ye look to the speech and fair words of a flatterer, paying no regard to any practical result.

Thus Solon. After he had gone into exile Pisistratus wrote to him as follows:

Pisistratus to Solon

53. “I am not the only man who has aimed at a tyranny in Greece, nor am I, a descendant of Codrus, unfitted for the part. That is, I resume the privileges which the Athenians swore to confer upon Codrus and his family, although later they took them away. In everything else I commit no offence against God or man; but I leave to the Athenians the management of their affairs according to the ordinances established by you. And they are better governed than they would be under a democracy; for I allow no one to extend his rights, and though I am tyrant I arrogate to myself no undue share of reputation and honour, but merely such stated privileges as belonged to the kings in former times. Every citizen pays a tithe of his property, not to me but to a fund for defraying the cost of the public sacrifices or any other charges on the State or the expenditure on any war which may come upon us.

54. “I do not blame you for disclosing my designs; you acted from loyalty to the city, not through any enmity to me, and further, in ignorance of the sort of rule which I was going to establish; since, if you had known, you would perhaps have tolerated me and not gone into exile. Wherefore return home, trusting my word, though it be not sworn, that Solon will suffer no harm from Pisistratus. For neither has any other enemy of mine suffered; of that you may be sure. And if you choose to become one of my friends, you will rank with the foremost, for I see no trace of treachery in you, nothing to excite mistrust; or if you wish to live at Athens on other terms, you have my permission. But do not on my account sever yourself from your country.

55. So far Pisistratus. To return to Solon: one of his sayings is that 70 years are the term of man’s life.

He seems to have enacted some admirable laws; for instance, if any man neglects to provide for his parents, he shall be disfranchised; moreover there is a similar penalty for the spendthrift who runs through his patrimony. Again, not to have a settled occupation is made a crime for which any one may, if he pleases, impeach the offender. Lysias, however, in his speech against Nicias ascribes this law to Draco, and to Solon another depriving open profligates of the right to speak in the Assembly. He curtailed the honours of athletes who took part in the games, fixing the allowance for an Olympic victor at 500 drachmae, for an Isthmian victor at 100 drachmae, and proportionately in all other cases. It was in bad taste, he urged, to increase the rewards of these victors, and to ignore the exclusive claims of those who had fallen in battle, whose sons ought, moreover, to be maintained and educated by the State.

56. The effect of this was that many strove to acquit themselves as gallant soldiers in battle, like Polyzelus, Cynegirus, Callimachus and all who fought at Marathon; or again like Harmodius and Aristogiton, and Miltiades and thousands more. Athletes, on the other hand, incur heavy costs while in training, do harm when successful, and are crowned for a victory over their country rather than over their rivals, and when they grow old they, in the words of Euripides,

Are worn threadbare, cloaks that have lost the nap;

and Solon, perceiving this, treated them with scant respect. Excellent, too, is his provision that the guardian of an orphan should not marry the mother of his ward, and that the next heir who would succeed on the death of the orphans should be disqualified from acting as their guardian. 57. Furthermore, that no engraver of seals should be allowed to retain an impression of the ring which he has sold, and that the penalty for depriving a one-eyed man of his single eye should be the loss of the offender’s two eyes. A deposit shall not be removed except by the depositor himself, on pain of death. That the magistrate found intoxicated should be punished with death.

He has provided that the public recitations of Homer shall follow in fixed order: thus the second reciter must begin from the place where the first left off. Hence, as Dieuchidas says in the fifth book of his Megarian History , Solon did more than Pisistratus to throw light on Homer. The passage in Homer more particularly referred to is that beginning “Those who dwelt at Athens ...”

58. Solon was the first to call the 30th day of the month the Old-and-New day, and to institute meetings of the nine archons for private conference, as stated by Apollodorus in the second book of his work On Legislators . When civil strife began, he did not take sides with those in the city, nor with the plain, nor yet with-the coast section.

One of his sayings is: Speech is the mirror of action; and another that the strongest and most capable is king. He compared laws to spiders’ webs, which stand firm when any light and yielding object falls upon them, while a larger thing breaks through them and makes off. Secrecy he called the seal of speech, and occasion the seal of secrecy. 59. He used to say that those who had influence with tyrants were like the pebbles employed in calculations; for, as each of the pebbles represented now a large and now a small number, so the tyrants would treat each one of those about them at one time as great and famous, at another as of no account. On being asked why he had not framed any law against parricide, he replied that he hoped it was unnecessary. Asked how crime could most effectually be diminished, he replied, “If it caused as much resentment in those who are not its victims as in those who are,” adding, “Wealth breeds satiety, satiety outrage.” He required the Athenians to adopt a lunar month. He prohibited Thespis from performing tragedies on the ground that fiction was pernicious. 60. When therefore Pisistratus appeared with self-inflicted wounds, Solon said, “This comes from acting tragedies.” His counsel to men in general is stated by Apollodorus in his work on the Philosophic Sects as follows: Put more trust in nobility of character than in an oath. Never tell a lie. Pursue worthy aims. Do not be rash to make friends and, when once they are made, do not drop them. Learn to obey before you command. In giving advice seek to help, not to please, your friend. Be led by reason. Shun evil company. Honour the gods, reverence parents. He is also said to have criticized the couplet of Mimnermus:

Would that by no disease, no cares opprest,

I in my sixtieth year were laid to rest;

61. and to have replied thus:

Oh take a friend’s suggestion, blot the line,

Grudge not if my invention better thine;

Surely a wiser wish were thus expressed,

At eighty years let me be laid to rest.

Of the songs sung this is attributed to Solon:

Watch every man and see whether, hiding hatred in his heart, he speaks with friendly countenance, and his tongue rings with double speech from a dark soul.

He is undoubtedly the author of the laws which bear his name; of speeches, and of poems in elegiac metre, namely, counsels addressed to himself, on Salamis and on the Athenian constitution, five thousand lines in all, not to mention poems in iambic metre and epodes.

62. His statue has the following inscription:

At Salamis, which crushed the Persian might,

Solon the legislator first saw light.

He flourished, according to Sosicrates, about the 46th Olympiad, in the third year of which he was archon at Athens; it was then that he enacted his laws. He died in Cyprus at the age of eighty. His last injunctions to his relations were on this wise: that they should convey his bones to Salamis and, when they had been reduced to ashes, scatter them over the soil. Hence Cratinus in his play, The Chirons , makes him say:

This is my island home; my dust, men say,

Is scattered far and wide o’er Ajax’ land.

63. An epigram of my own is also contained in the collection of Epigrams in Various Metres mentioned above, where I have discoursed of all the illustrious dead in all metres and rhythms, in epigrams and lyrics. Here it is:

Far Cyprian fire his body burnt; his bones,

Turned into dust, made grain at Salamis:

Wheel-like, his pillars bore his soul on high;

So light the burden of his laws on men.

It is said that he was the author of the apophthegm “Nothing too much,” Ne quid nimis . According to Dioscurides in his Memorabilia , when he was weeping for the loss of his son, of whom nothing more is known, and some one said to him, “It is all of no avail,” he replied, “That is why I weep, because it is of no avail.”

The following letters are attributed to Solon:

Solon to Periander

64. “You tell me that many are plotting against you. You must lose no time if you want to get rid of them all. A conspirator against you might arise from a quite unexpected quarter, say, one who had fears for his personal safety or one who disliked your timorous dread of anything and everything. He would earn the gratitude of the city who found out that you had no suspicion. The best course would be to resign power, and so be quit of the reproach. But if you must at all hazards remain tyrant, endeavour to make your mercenary force stronger than the forces of the city. Then you have no one to fear, and need not banish any one.”

Solon to Epimenides

“It seems that after all I was not to confer much benefit on Athenians by my laws, any more than you by purifying the city. For religion and legislation are not sufficient in themselves to benefit cities; it can only be done by those who lead the multitude in any direction they choose. And so, if things are going well, religion and legislation are beneficial; if not, they are of no avail.

65. “Nor are my laws nor all my enactments any better; but the popular leaders did the commonwealth harm by permitting licence, and could not hinder Pisistratus from setting up a tyranny. And, when I warned them, they would not believe me. He found more credit when he flattered the people than I when I told them the truth. I laid my arms down before the generals’ quarters and told the people that I was wiser than those who did not see that Pisistratus was aiming at tyranny, and more courageous than those who shrank from resisting him. They, however, denounced Solon as mad. And at last I protested: “My country, I, Solon, am ready to defend thee by word and deed; but some of my countrymen think me mad. Wherefore I will go forth out of their midst as the sole opponent of Pisistratus; and let them, if they like, become his bodyguard.” For you must know, my friend, that he was beyond measure ambitious to be tyrant. “ 66. He began by being a popular leader; his next step was to inflict wounds on himself and appear before the court of the Heliaea, crying out that these wounds had been inflicted by his enemies; and he requested them to give him a guard of 400 young men. And the people without listening to me granted him the men, who were armed with clubs. And after that he destroyed the democracy. It was in vain that I sought to free the poor amongst the Athenians from their condition of serfdom, if now they are all the slaves of one master, Pisistratus.”

Solon to Pisistratus

“I am sure that I shall suffer no harm at your hands; for before you became tyrant I was your friend, and now I have no quarrel with you beyond that of every Athenian who disapproves of tyranny. Whether it is better for them to be ruled by one man or to live under a democracy, each of us must decide for himself upon his own judgement. 67. You are, I admit, of all tyrants the best; but I see that it is not well for me to return to Athens. I gave the Athenians equality of civil rights; I refused to become tyrant when I had the opportunity; how then could I escape censure if I were now to return and set my approval on all that you are doing?”

Solon to Croesus

“I admire you for your kindness to me; and, by Athena, if I had not been anxious before all things to live in a democracy, I would rather have fixed my abode in your palace than at Athens, where Pisistratus is setting up a rule of violence. But in truth to live in a place where all have equal rights is more to my liking. However, I will come and see you, for I am eager to make your acquaintance.”

68. Chilon, son of Damagetas, was a Lacedaemonian. He wrote a poem in elegiac metre some 200 lines in length; and he declared that the excellence of a man is to divine the future so far as it can be grasped by reason. When his brother grumbled that he was not made ephor as Chilon was, the latter replied, “I know how to submit to injustice and you do not.” He was made ephor in the 55th Olympiad; Pamphila, however, says the 56th. He first became ephor, according to Sosicrates, in the archonship of Euthydemus. He first proposed the appointment of ephors as auxiliaries to the kings, though Satyrus says this was done by Lycurgus.

As Herodotus relates in his first book, when Hippocrates was sacrificing at Olympia and his cauldrons boiled of their own accord, it was Chilon who advised him not to marry, or, if he had a wife, to divorce her and disown his children. 69. The tale is also told that he inquired of Aesop what Zeus was doing and received the answer: “He is humbling the proud and exalting the humble.” Being asked wherein lies the difference between the educated and the uneducated, Chilon answered, “In good hope.” What is hard? “To keep a secret, to employ leisure well, to be able to bear an injury.” These again are some of his precepts: To control the tongue, especially at a banquet. 70. Not to abuse our neighbours, for if you do, things will be said about you which you will regret. Do not use threats to any one; for that is womanish. Be more ready to visit friends in adversity than in prosperity. Do not make an extravagant marriage. De mortuis nil nisi bonum . Honour old age. Consult your own safety. Prefer a loss to a dishonest gain: the one brings pain at the moment, the other for all time. Do not laugh at another’s misfortune. When strong, be merciful, if you would have the respect, not the fear, of your neighbours. Learn to be a wise master in your own house. Let not your tongue outrun your thought. Control anger. Do not hate divination. Do not aim at impossibilities. Let no one see you in a hurry. Gesticulation in speaking should be avoided as a mark of insanity. Obey the laws. Be restful.

71. Of his songs the most popular is the following: “By the whetstone gold is tried, giving manifest proof; and by gold is the mind of good and evil men brought to the test.” He is reported to have said in his old age that he was not aware of having ever broken the law throughout his life; but on one point he was not quite clear. In a suit in which a friend of his was concerned he himself pronounced sentence according to the law, but he persuaded his colleague who was his friend to acquit the accused, in order at once to maintain the law and yet not to lose his friend.

He became very famous in Greece by his warning about the island of Cythera off the Laconian coast. For, becoming acquainted with the nature of the island, he exclaimed: “Would it had never been placed there, or else had been sunk in the depths of the sea.” 72. And this was a wise warning; for Demaratus, when an exile from Sparta, advised Xerxes to anchor his fleet off the island; and if Xerxes had taken the advice Greece would have been conquered. Later, in the Peloponnesian war, Nicias reduced the island and placed an Athenian garrison there, and did the Lacedaemonians much mischief.

He was a man of few words; hence Aristagoras of Miletus calls this style of speaking Chilonean. . . . is of Branchus, founder of the temple at Branchidae. Chilon was an old man about the 52nd Olympiad, when Aesop the fabulist was flourishing. According to Hermippus, his death took place at Pisa, just after he had congratulated his son on an Olympic victory in boxing. It was due to excess of joy coupled with the weakness of a man stricken in years. And all present joined in the funeral procession.

I have written an epitaph on him also, which runs as follows:

73. I praise thee, Pollux, for that Chilon’s son

By boxing feats the olive chaplet won.

Nor at the father’s fate should we repine;

He died of joy; may such a death be mine.

The inscription on his statue runs thus:

Here Chilon stands, of Sparta’s warrior race,

Who of the Sages Seven holds highest place.

His apophthegm is: “Give a pledge, and suffer for it.” A short letter is also ascribed to him.

Chilon to Periander

“You tell me of an expedition against foreign enemies, in which you yourself will take the field. In my opinion affairs at home are not too safe for an absolute ruler; and I deem the tyrant happy who dies a natural death in his own house.”

74. Pittacus was the son of Hyrrhadius and a native of Mitylene. Duris calls his father a Thracian. Aided by the brothers of Alcaeus he overthrew Melanchrus, tyrant of Lesbos; and in the war between Mitylene and Athens for the territory of Achileis he himself had the chief command on the one side, and Phrynon, who had won an Olympic victory in the pancratium, commanded the Athenians. Pittacus agreed to meet him in single combat; with a net which he concealed beneath his shield he entangled Phrynon, killed him, and recovered the territory. Subsequently, as Apollodorus states in his Chronology , Athens and Mitylene referred their claims to arbitration. Periander heard the appeal and gave judgement in favour of Athens.

75. At the time, however, the people of Mitylene honoured Pittacus extravagantly and entrusted him with the government. He ruled for ten years and brought the constitution into order, and then laid down his office. He lived another ten years after his abdication and received from the people of Mitylene a grant of land, which he dedicated as sacred domain; and it bears his name to this day Sosicrates relates that he cut off a small portion for himself and pronounced the half to be more than the whole. Furthermore, he declined an offer of money made him by Croesus, saying that he had twice as much as he wanted; for his brother had died without issue and he had inherited his estate.

76. Pamphila in the second book of her Memorabilia narrates that, as his son Tyrraeus sat in a barber’s shop in Cyme, a smith killed him with a blow from an axe. When the people of Cyme sent the murderer to Pittacus, he, on learning the story, set him at liberty and declared that “It is better to pardon now than to repent later.” Heraclitus, however, says that it was Alcaeus whom he set at liberty when he had got him in his power, and that what he said was: “Mercy is better than vengeance.”

Among the laws which he made is one providing that for any offence committed in a state of intoxication the penalty should be doubled; his object was to discourage drunkenness, wine being abundant in the island. One of his sayings is, “It is hard to be good,” which is cited by Simonides in this form: “Pittacus’s maxim, ‘Truly to become a virtuous man is hard.’” 77. Plato also cites him in the Protagoras : “Even the gods do not fight against necessity.” Again, “Office shows the man.” Once, when asked what is the best thing, he replied, “To do well the work in hand.” And, when Croesus inquired what is the best rule, he answered, “The rule of the shifting wood,” by which he meant the law. He also urged men to win bloodless victories. When the Phocaean said that we must search for a good man, Pittacus rejoined, “If you seek too carefully, you will never find him.” He answered various inquiries thus: “What is agreeable?” “Time.” “Obscure?” “The future.” “Trustworthy?” “The earth.” “Untrustworthy?” “The sea.” “It is the part of prudent men,” he said, “before difficulties arise, to provide against their arising; 78. and of courageous men to deal with them when they have arisen.” Do not announce your plans beforehand; for, if they fail, you will be laughed at. Never reproach any one with a misfortune, for fear of Nemesis. Duly restore what has been entrusted to you. Speak no ill of a friend, nor even of an enemy. Practise piety. Love temperance. Cherish truth, fidelity, skill, cleverness, sociability, carefulness.

Of his songs the most popular is this:

With bow and well-stored quiver

We must march against our foe,

Words of his tongue can no man trust,

For in his heart there is a deceitful thought.

79. He also wrote poems in elegiac metre, some 600 lines, and a prose work On Laws for the use of the citizens.

He was flourishing about the 42nd Olympiad. He died in the archonship of Aristomenes, in the third year of the 52nd Olympiad, having lived more than seventy years, to a good old age. The inscription on his monument runs thus:

Here holy Lesbos, with a mother’s woe,

Bewails her Pittacus whom death laid low.

To him belongs the apophthegm, “Know thine opportunity.”

There was another Pittacus, a legislator, as is stated by Favorinus in the first book of his Memorabilia , and by Demetrius in his work on Men of the Same Name . He was called the Less.

To return to the Sage: the story goes that a young man took counsel with him about marriage, and received this answer, as given by Callimachus in his Epigrams :

80. A stranger of Atarneus thus inquired of Pittacus, the son of Hyrrhadius:

Old sire, two offers of marriage are made to me; the one bride is in wealth and birth my equal;

The other is my superior. Which is the better? Come now and advise me which of the two I shall wed.

So spake he. But Pittacus, raising his staff, an old man’s weapon, said, “See there, yonder boys will tell you the whole tale.”

The boys were whipping their tops to make them go fast and spinning them in a wide open space.

“Follow in their track,” said he. So he approached near, and the boys were saying, “Keep to your own sphere.”

When he heard this, the stranger desisted from aiming at the lordlier match, assenting to the warning of the boys.

And, even as he led home the humble bride, so do you, Dion, keep to your own sphere.

81. The advice seems to have been prompted by his situation. For he had married a wife superior in birth to himself: she was the sister of Draco, the son of Penthilus, and she treated him with great haughtiness.

Alcaeus nicknamed him σαράπους and σάραπος because he had flat feet and dragged them in walking; also “Chilblains,” because he had chapped feet, for which their word was χειράς; and Braggadocio, because he was always swaggering; Paunch and Potbelly, because he was stout; a Diner-in-the-Dark, because he dispensed with a lamp; and the Sloven, because he was untidy and dirty. The exercise he took was grinding corn, as related by Clearchus the philosopher.

The following short letter is ascribed to him:

Pittacus to Croesus

“You bid me come to Lydia in order to see your prosperity: but without seeing it I can well believe that the son of Alyattes is the most opulent of kings. There will be no advantage to me in a journey to Sardis, for I am not in want of money, and my possessions are sufficient for my friends as well as myself. Nevertheless, I will come, to be entertained by you and to make your acquaintance.”

82. Bias, the son of Teutames, was born at Priene, and by Satyrus is placed at the head of the Seven Sages. Some make him of a wealthy family, but Duris says he was a labourer living in the house. Phanodicus relates that he ransomed certain Messenian maidens captured in war and brought them up as his daughters, gave them dowries, and restored them to their fathers in Messenia. In course of time, as has been already related, the bronze tripod with the inscription “To him that is wise” having been found at Athens by the fishermen, the maidens according to Satyrus, or their father according to other accounts, including that of Phanodicus, came forward into the assembly and, after the recital of their own adventures, pronounced Bias to be wise. And thereupon the tripod was dispatched to him; but Bias, on seeing it, declared that Apollo was wise, and refused to take the tripod. 83. But others say that he dedicated it to Heracles in Thebes, since he was a descendant of the Thebans who had founded a colony at Priene; and this is the version of Phanodieus.

A story is told that, while Alyattes was besieging Priene, Bias fattened two mules and drove them into the camp, and that the king, when he saw them, was amazed at the good condition of the citizens actually extending to their beasts of burden. And he decided to make terms and sent a messenger. But Bias piled up heaps of sand with a layer of corn on the top, and showed them to the man, and finally, on being informed of this, Alyattes made a treaty of peace with the people of Priene. Soon afterwards, when Alyattes sent to invite Bias to his court, he replied, “Tell Alyattes, from me, to make his diet of onions,” that is, to wee . It is also stated that he was a very effective pleader; but he was accustomed to use his powers of speech to a good end. Hence it is to this that Demodicus of Leros makes reference in the line:

If you happen to be prosecuting a suit, plead as they do at Priene;

and Hipponax thus: “More powerful in pleading causes than Bias of Priene.”

This was the manner of his death. He had been pleading in defence of some client in spite of his great age. When he had finished speaking, he reclined his head on his grandson’s bosom. The opposing counsel made a speech, the judges voted and gave their verdict in favour of the client of Bias, who, when the court rose, was found dead in his grandson’s arms. 85. The city gave him a magnificent funeral and inscribed on his tomb:

Here Bias of Priene lies, whose name

Brought to his home and all Ionia fame.

My own epitaph is:

Here Bias rests. A quiet death laid low

The aged head which years had strewn with snow.

His pleading done, his friend preserved from harms,

A long sleep took him in his grandson’s arms.

He wrote a poem of 2000 lines on Ionia and the manner of rendering it prosperous. Of his songs the most popular is the following:

Find favour with all the citizens . . . . . . in whatever state you dwell.

For this earns most gratitude; the headstrong spirit often flashes forth with harmful bane.

86. The growth of strength in man is nature’s work; but to set forth in speech the interests of one’s country is the gift of soul and reason. Even chance brings abundance of wealth to many. He also said that he who could not bear misfortune was truly unfortunate; that it is a disease of the soul to be enamoured of things impossible of attainment; and that we ought not to dwell upon the woes of others. Being asked what is difficult, he replied, “Nobly to endure a change for the worse.” He was once on a voyage with some impious men; and, when a storm was encountered, even they began to call upon the gods for help. “Peace!” said he, “lest they hear and become aware that you are here in the ship.” When an impious man asked him to define piety, he was silent; and when the other inquired the reason, “I am silent,” he replied, “because you are asking questions about what does not concern you.”

87. Being asked “What is sweet to men,” he answered, “Hope.” He said he would rather decide a dispute between two of his enemies than between two of his friends; for in the latter case he would be certain to make one of his friends his enemy, but in the former case he would make one of his enemies his friend. Asked what occupation gives a man most pleasure, he replied, “Making money.” He advised men to measure life as if they had both a short and a long time to live; to love their friends as if they would some day hate them, the majority of mankind being bad. Further, he gave this advice: Be slow to set about an enterprise, but persevere in it steadfastly when once it is undertaken. Do not be hasty of speech, for that is a sign of madness. 88. Cherish wisdom. Admit the existence of the gods. If a man is unworthy, do not praise him because of his wealth. Gain your point by persuasion, not by force. Ascribe your good actions to the gods. Make wisdom your provision for the journey from youth to old age; for it is a more certain support than all other possessions.

Bias is mentioned by Hipponax as stated above, and Heraclitus, who is hard to please, bestows upon him especial praise in these words: “In Priene lived Bias, son of Teutames, a man of more consideration than any.” And the people of Priene dedicated a precinct to him, which is called the Teutameum. His apophthegm is: Most men are bad.

89. Cleobulus, the son of Euagoras, was born at Lindus, but according to Duris he was a Carian. Some say that he traced his descent back to Heracles, that he was distinguished for strength and beauty, and was acquainted with Egyptian philosophy. He had a daughter Cleobuline, who composed riddles in hexameters; she is mentioned by Cratinus, who gives one of his plays her name, in the plural form Cleobulinae. He is also said to have rebuilt the temple of Athena which was founded by Danaus.

He was the author of songs and riddles, making some 3000 lines in all.

The inscription on the tomb of Midas is said by some to be his:

I am a maiden of bronze and I rest upon Midas’s tomb. So long as water shall flow and tall trees grow, and the sun shall rise and shine, 90. and the bright moon, and rivers shall run and the sea wash the shore, here abiding on his tearsprinkled tomb I shall tell the passers-by – Midas is buried here.

The evidence they adduce is a poem of Simonides in which he says:

Who, if he trusts his wits, will praise Cleobulus the dweller at Lindus for opposing the strength of a column to everflowing rivers, the flowers of spring, the flame of the sun, and the golden moon and the eddies of the sea? But all things fall short of the might of the gods; even mortal hands break marble in pieces; this is a fool’s devising.

The inscription cannot be by Homer, because he lived, they say, long before Midas.

The following riddle of Cleobulus is preserved in Pamphila’s collection:

91. One sire there is, he has twelve sons, and each of these has twice thirty daughters different in feature; some of the daughters are white, the others again are black; they are immortal, and yet they all die.

And the answer is, “The year.”

Of his songs the most popular are: It is want of taste that reigns most widely among mortals and multitude of words; but due season will serve. Set your mind on something good. Do not become thoughtless or rude. He said that we ought to give our daughters to their husbands maidens in years but women in wisdom; thus signifying that girls need to be educated as well as boys. Further, that we should render a service to a friend to bind him closer to us, and to an enemy in order to make a friend of him. For we have to guard against the censure of friends and the intrigues of enemies. 92. When anyone leaves his house, let him first inquire what he means to do; and on his return let him ask himself what he has effected. Moreover, he advised men to practise bodily exercise; to be listeners rather than talkers; to choose instruction rather than ignorance; to refrain from ill-omened words; to be friendly to virtue, hostile to vice; to shun injustice; to counsel the state for the best; not to be overcome by pleasure; to do nothing by violence; to educate their children; to put an end to enmity. Avoid being affectionate to your wife, or quarrelling with her, in the presence of strangers; for the one savours of folly, the other of madness. Never correct a servant over your wine, for you will be thought to be the worse for wine. Mate with one of your own rank; for if you take a wife who is superior to you, her kinsfolk will become your masters. 93. When men are being bantered, do not laugh at their expense, or you will incur their hatred. Do not be arrogant in prosperity; if you fall into poverty, do not humble yourself. Know how to bear the changes of fortune with nobility.

He died at the ripe age of seventy; and the inscription over him is:

Here the wise Rhodian, Cleobulus, sleeps,

And o’er his ashes sea-proud Lindus weeps.

His apophthegm was: Moderation is best. And he wrote to Solon the following letter:

Cleobulus to Solon

“You have many friends and a home wherever you go; but the most suitable for Solon will, say I, be Lindus, which is governed by a democracy. The island lies on the high seas, and one who lives here has nothing to fear from Pisistratus. And friends from all parts will come to visit you.”

94. Periander, the son of Cypselus, was born at Corinth, of the family of the Heraclidae. His wife was Lysida, whom he called Melissa. Her father was Procles, tyrant of Epidaurus, her mother Eristheneia, daughter of Aristocrates and sister of Aristodemus, who together reigned over nearly the whole of Arcadia, as stated by Heraclides of Pontus in his book On Government . By her he had two sons, Cypselus and Lycophron, the younger a man of intelligence, the elder weak in mind. 95. However, after some time, in a fit of anger, he killed his wife by throwing a footstool at her, or by a kick, when she was pregnant, having been egged on by the slanderous tales of concubines, whom he afterwards burnt alive.

When the son whose name was Lycophron grieved for his mother, he banished him to Corcyra. And when well advanced in years he sent for his son to be his successor in the tyranny; but the Corcyraeans put him to death before he could set sail. Enraged at this, he dispatched the sons of the Corcyraeans to Alyattes that he might make eunuchs of them; but, when the ship touched at Samos, they took sanctuary in the temple of Hera, and were saved by the Samians.

Periander lost heart and died at the age of eighty. Sosicrates’ account is that he died fortyone years before Croesus, just before the 49th Olympiad. Herodotus in his first book says that he was a guest-friend of Thrasybulus, tyrant of Miletus.

96. Aristippus in the first book of his work On the Luxury of the Ancients accuses him of incest with his own mother Crateia, and adds that, when the fact came to light, he vented his annoyance in indiscriminate severity. Ephorus records his now that, if he won the victory at Olympia in the chariot-race, he would set up a golden statue. When the victory was won, being in sore straits for gold, he despoiled the women of all the ornaments which he had seen them wearing at some local festival. He was thus enabled to send the votive offering.

There is a story that he did not wish the place where he was buried to be known, and to that end contrived the following device. He ordered two young men to go out at night by a certain road which he pointed out to them; they were to kill the man they met and bury him. He afterwards ordered four more to go in pursuit of the two, kill them and bury them; again, he dispatched a larger number in pursuit of the four. Having taken these measures, he himself encountered the first pair and was slain. The Corinthians placed the following inscription upon a cenotaph:

97. In mother earth here Periander lies,

The prince of sea-girt Corinth rich and wise.

My own epitaph on him is:

Grieve not because thou hast not gained thine end,

But take with gladness all the gods may send;

Be warned by Periander’s fate, who died

Of grief that one desire should be denied.

To him belongs the maxim: Never do anything for money; leave gain to trades pursued for gain. He wrote a didactic poem of 2000 lines. He said that those tyrants who intend to be safe should make loyalty their bodyguard, not arms. When some one asked him why he was tyrant, he replied, “Because it is as dangerous to retire voluntarily as to be dispossessed.” Here are other sayings of his: Rest is beautiful. Rashness has its perils. Gain is ignoble. Democracy is better than tyranny. Pleasures are transient, honours are immortal. 98. Be moderate in prosperity, prudent in adversity. Be the same to your friends whether they are in prosperity or in adversity. Whatever agreement you make, stick to it. Betray no secret. Correct not only the offenders but also those who are on the point of offending.

He was the first who had a bodyguard and who changed his government into a tyranny, and he would let no one live in the town without his permission, as we know from Ephorus and Aristotle.

He flourished about the 38th Olympiad and was tyrant for forty years.

Sotion and Heraclides and Pamphila in the fifth book of her Commentaries distinguish two Perianders, one a tyrant, the other a sage who was born in Ambracia. 99. Neanthes of Cyzicus also says this, and adds that they were near relations. And Aristotle maintains that the Corinthian Periander was the sage; while Plato denies this.

His apophthegm is: Practice makes perfect. He planned a canal across the Isthmus.

A letter of his is extant:

Periander to the Wise Men

“Very grateful am I to the Pythian Apollo that I found you gathered together; and my letters will also bring you to Corinth, where, as you know, I will give you a thoroughly popular reception. I learn that last year you met in Sardis at the Lydian court. Do not hesitate therefore to come to me, the ruler of Corinth. The Corinthians will be pleased to see you coming to the house of Periander.”

Periander to Procles

100. “The murder of my wife was unintentional; but yours is deliberate guilt when you set my son’s heart against me. Either therefore put an end to my son’s harsh treatment, or I will revenge myself on you. For long ago I made expiation to you for your daughter by burning on her pyre the apparel of all the women of Corinth.”

There is also a letter written to him by Thrasybulus, as follows:

Thrasybulus to Periander