10

Hypervisibility and Invisibility of Female Haafu Models in Japan’s Beauty Culture

Kaori Mori Want

Japan’s representative for the 2015 Miss Universe Pageant surprised many Japanese. The Miss Universe committee chose Ariana Miyamoto, a model, whose mother is Japanese and father is African American. The Japanese were surprised for two main reasons. First, Miyamoto is haafu, meaning half Japanese, who has part non-Japanese ancestry. Second, she has dark skin. Upon the announcement of Miyamoto’s selection, there arose controversy among the Japanese. Some said that since Miss Universe is a representative of a nation’s beauty, Miyamoto was not qualified because of her non-Japanese ancestry.1 Her skin color was not overtly criticized, but the references to her not looking Japanese enough implied that her skin color was a problem.

While Miyamoto’s haafu status was highly criticized, popular Japanese fashion magazines feature many haafu models. Most of them are half White and half Japanese or Asian. Japanese are accustomed to the presence of White female haafu models in Japan’s beauty culture. White female haafu models embody beauty, which Japanese women admire. The Japanese have no problem viewing haafu models as the standard of beauty, yet Miyamoto shocked many Japanese because she challenged the general assumption of beauty. Miyamoto’s presence was like an invisible ghost appearing in the daytime. Non-White female haafu models have been rendered invisible in Japan’s beauty culture. In this chapter, I explore why they have been erased and how their presence challenges the Japanese perception of beauty.

In order to understand the invisibility of non-White female haafu models in Japan’s beauty culture, this chapter first explains the overwhelming popularity of White female haafu models in Japan’s beauty culture with a special focus on fashion and the cosmetics industry. I trace Japanese beauty history to see how Japanese people came to valorize light skin and Caucasian facial features. Then, the chapter examines why non-White female haafu models in beauty culture are rendered invisible by applying the concepts of transnational lovely White ideology and local kawaii (cuteness) ideology, which is culturally specific to the Japanese context. This illustrates how two ideologies exclude non-White female haafu models from Japan’s beauty culture.

This chapter uses the term “haafu” to describe mixed race/ethnic Japanese.2 The word derived from the English word “half.” Haafu generally means people with half Japanese and half non-Japanese heritage. For example, a person with a Japanese father and an African mother is haafu. Using the term “haafu” to express mixed race/ethnic Japanese is controversial because those of mixed race/ethnicity who were born and raised and live in Japan are considered fully Japanese.3 However, the term treats those of mixed race/ethnicity as not Japanese enough. The term “haafu” has circulated in Japan, and mixed race/ethnic Japanese use the term to represent themselves.4 This chapter uses the term while acknowledging its problems.

Popularity of White Female Haafu Models in the Fashion and Cosmetics Industries

The social position of haafu is characterized by their hypervisibility and invisibility. They are hypervisible in the media. They have been popular as actors, singers, anchors, athletes, and models since the 1960s, a period that witnessed the emergence of many haafu stars such as Bibari Maeda, Linda Yamamoto, and Masao Kusakari, to name a few.

After the 1945 Japanese defeat in World War II, the Allied servicemen, mainly Americans, came to occupy the country with a mission of democratizing militaristic Japan. The General Headquarters of the Allied forces banned intimacy between Japanese women and American servicemen, and strengthened their nonfraternizing policy. Nevertheless, some servicemen had legitimate and illegitimate mixed race/ethnic children with Japanese women. Japanese women who had children with American servicemen were called panpan (prostitutes), even though they were not, and they were exposed to harsh prejudice.

Mixed race/ethnic children were also regarded as the offspring of prostitutes and discriminated against. Black mixed race children suffered more discrimination than White mixed race children because Japanese people looked down on dark skin.5 Under this difficult social environment, many of these mixed race/ethnic children reached their teens or twenties in the 1960s. Having non-Japanese heritage gave them a unique physical difference that fascinated Japanese audiences. They became popular and achieved hypervisibility in show business. That period is referred to as the first haafu boom.6 In fact, the term “haafu” is said to have originated with a once popular girl group, Golden Half, which consisted of four mixed race Japanese girls.7

Haafu entertainers remain popular today. While haafu entertainers in the 1960s were marred by the negative stereotype as being the illegitimate children of Japanese women and American servicemen, contemporary haafu entertainers are not susceptible to that kind of negative stereotype because the postwar stereotype of haafu is mostly just a memory. The negative stereotypes were wiped away with the strong influence of Western, especially American, culture. The 2000s witnessed the second haafu boom.8 Japanese women admire haafu female celebrities’ faces, which are characterized by big eyelids, long eyelashes, high noses, and full lips. The cosmetics industry has taken advantage of the haafu boom among Japanese women and produced haafu cosmetics, which allegedly make a typical flat Japanese face look haafu. They sell cosmetics such as lip creams, false eyelashes, eye shadow, and so on. Magazines also feature articles on how to produce a haafu-like face with makeup.

What is problematic about this popularity of haafu is that the admired face of haafu is half White and half Japanese. Non-White haafu, such as those who are part Black or part Brown, are virtually invisible in this phenomenon.9 This does not mean that non-White haafu do not exist. Model agencies featuring non-Japanese and haafu models such as REMIX, Free Wave, and Zenith have non-White haafu models. For example, REMIX has a category of Black female models. Of the twenty-six Black models, seven seem to be haafu according to their ethnic profile. Yet, they are rarely seen in Japanese fashion magazines or the advertisements of cosmetics companies. While there are numerous White female haafu models in fashion magazines, it is rare to see non-White female haafu models. In this sense, non-White female haafu models are made to be invisible in Japan.

Another problem of the invisibility of non-White female models in Japan’s beauty culture is that it is gender-specific. We can see some male haafu models regardless of skin color in Japanese fashion magazines. Having dark skin is seen as virile and acceptable for men in Japan. Yet dark skin is not regarded as a sign of female beauty because light skin has been traditionally a standard of beauty. The desire for White haafu beauty is thus gender-specific. With that, I also address the invisibility of non-White female models in Japan’s beauty industry.

Analysis of the Japanese Fascination with Whiteness and Repulsion of Darkness

Japanese fashion magazines have many White female haafu models. For example, in September 2012 the fashion magazine Runway featured seven models, five of them White female haafu models, two others non-haafu Japanese.10 The magazine did not use dark-skinned haafu models in this issue. A photo book, Life as a Golden Half, featured eleven haafu models, and all White female haafu models. The book cover declared that “the life of haafu models is shining! They are all girls’ object of admiration.”11 White female haafu models are a fashion icon, whom Japanese women admire and emulate.

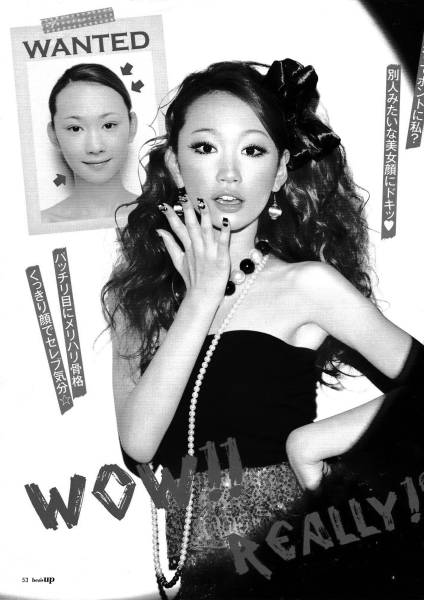

Some fashion magazines feature articles on how to create a White female haafu look. For example, the fashion magazine Bea’s UP featured an article titled “Haafu Face Recipe” (see figure 10.1).12 In this article, a cosmetician, Toshihito Tamura, demonstrates how to make a typical Japanese face look like haafu. The author writes, “All girls want to have big eyes, a face with chiseled features, small face, and full lips. They admire the haafu face. If you feel it is impossible to have the haafu face, Tamura will make your dreams come true.”13 Responding to Japanese girls’ dreams, Tamura shows readers how to transform their face. The article shows a model who is surprised by her new look with haafu makeup who screams, “Wow!! Really!” From these magazines, we can see how the haafu face is admired by Japanese girls, and how popular it is.

Figure 10.1. “Haafu Face Recipe,” Bea’s UP (December 1, 2009): 52.

The fascination with White female haafu models is not a recent phenomenon. As noted, when mixed race/ethnic children of Japanese women and American servicemen reached their teens and twenties in the 1960s, their physical difference attracted popularity in Japan’s media, although a social environment that discriminated against them existed at the time. Many cosmetics companies have featured White female haafu models for their TV commercials to promote their products since the 1960s. Since cosmetics companies have created the trend for Japanese women, White female haafu faces have become the ideal face for Japanese women.

Hiroshi Wagatsuma and Toshinao Yoneyama trace the history of Japan’s beauty culture and explain Japanese women’s complex desire for light skin and Caucasian facial features. They contend that Japanese women’s desire for Western beauty focuses on a desire for Caucasian facial features (not skin tone). Wagatsuma and Yoneyama write that Japanese women started using whitening powder in the Nara period (710–794) under the influence of Chinese culture. Since then, light skin has been a standard of female beauty in Japan.14 Wagasuma and Yoneyama point out that Japanese women found Caucasian skin ugly because their skin was “not smooth, and had too many wrinkles.”15 They note that until the end of the Edo era (1603–1868), beautiful Japanese women had single eyelid eyes.16 Caucasian faces were once regarded as monstrous because of their physical difference from the Japanese.17 According to Wagasuma and Yoneyama, Japanese women’s fascination with Caucasian face is a recent phenomenon. A Caucasian face was desired in Taisho era (1912–1926) when Western culture became popular.18 The Japanese Westernization project in the mid-twentieth century influenced the standard of beauty, and the Caucasian face became idealized as a standard of female beauty. Light skin, which Japanese women admire, is derived not from Western influence, but from Chinese culture. Japanese women have been fascinated by Caucasian facial features, but not their skin. This is unique, in that Japanese beauty culture is not totally dominated by Western beauty ideology, as is the case in other countries.

Joanne Rondilla and Paul Spickard analyze the popularity of light skin in the cosmetics industry and demonstrate how it affects Filipino women’s desire for light skin in their Is Lighter Better?. According to their analysis, transnational cosmetics companies such as L’Oreal and Esolis have use mixed race models with Asian and Caucasian heritage for their advertisements in the Philippines, trying to spread the lovely White ideology among Filipino women.19 Wendy Chapkis explains what lovely White ideology is and writes, “Indeed, female beauty is becoming an increasingly standardized quality throughout the world. A standard so strikingly White, Western, and wealthy.”20 Under this ideology, women in the world strive to have light skin, Western facial features, and an affluent lifestyle.

The popularity of White female haafu models may be due to Japanese women’s fascination with light skin and Caucasian facial features, influenced by lovely White ideology. Haafu have both traits—light skin and Caucasian facial features—that Japanese women admire. It seems that light skin and Caucasian facial features are the only prerequisites to become a popular White female haafu model. Julie Matthews analyzes the popularity of mixed race models in Asia and the West in her article “Eurasian Persuasions: Mixed Race, Performativity and Cosmopolitanism.” She points out that their popularity rests on their “sameness and as much as difference.”21 Matthews analyzes the popularity of mixed race models in countries where Caucasians are the majority. Asianness marks difference, Whiteness sameness in her article. In Japan, the situation is opposite as Whiteness is the marker of difference. However, her analysis of the mixed race models as the embodiment of sameness and difference is useful in examining the popularity of White female haafu models in Japan. White female haafu models are different because they have Caucasian features but are the same as the general Japanese because most White female haafu models are part Japanese or part Asian. Their Asian heritage mitigates their difference. If cosmetic and fashion models are Caucasian women, they are physically too distant from Japanese women, and Japanese women cannot identify with those models. In fact, despite the fact that the Caucasian face has become popular, Wagatsuma and Yoneyama write that Japanese people still find the Caucasian face to be different from theirs and do not fully identify with it.22 On the other hand, Japanese women may find White female haafu models possible to copy. Yet, White female haafu models cannot be popular just for having a Western and Japanese racial heritage. If so, any haafu could achieve success, which is not the case. I argue that alongside the transnational lovely White ideology, there is a local ideology that enables the popularity of White female haafu models in Japan: kawaii.

The Japanese beauty industry operates according to the concept of kawaii, which means cuteness. It is a culturally specific notion. A lovable woman in Japan must be kawaii. The definition of kawaii comes from Japanese people’s feeling toward babies. Babies are soft, small, innocent, White, and vulnerable. Japanese women desire cosmetic products and clothing that can make them kawaii, meaning light, small, and vulnerable. They support models who can embody kawaii. Kawaii ideology excludes darkness from its scope because it favors lightness. The notion opposite to kawaii is ugliness and undesirability, which in many societies (including Japan) are associated with darkness. This may be one of the reasons that non-White female models are invisible in Japan’s beauty culture. We will see how dark skin has been rendered undesirable in Japanese society by exploring the voices of non-White female haafu.

A Complex Social Gaze toward Dark Skin in Japan

As we have seen, while the Caucasian face and light skin are idealized in Japan, dark skin has been relegated to an undesirable position. Some scholars have explained why dark skin has been rejected by the Japanese. For example, John Russell examines the representations of Black people in Japanese literature and the mass media and concludes that Japanese people see Black people as “not human but animal, ugly, infantile, and different.”23 Wagatsuma and Yoneyama share a similar view of the Japanese perception of Black people. They contend that Japanese people regard Black people as “spooky, scary, dirty, animal-like, and different.”24 A similar view on dark skin is still seen in the media today. For example, Atsuhisa Yamamoto argues that Blackness is seen as “violent and criminal” by analyzing the criminal case of Rion Ito, a haafu with Black heritage. He belonged to a gang and was involved in the battering of a famous Kabuki actor in 2010, and became a target of mass media scandal. Yamamoto problematizes the mass media’s association of Ito’s crime with his Blackness.25

Some dark-skinned haafu recount their experiences of being exposed to a discriminatory social gaze toward their skin. From their voices, we can see the stereotypes inscribed on the dark-skinned haafu. Keiko Kozeki is a daughter of a Japanese mother and an African American serviceman father. She was born during the US occupation of Japan (1945–1952), and wrote of her experiences in a 1960s memoir. She experienced hardship in her upbringing. She was abandoned by both parents, was raised by poor stepparents, and had no access to education or a well-paid job. Most of all, she suffered from her dark skin. She writes, “When I was on a train one day, two university students talked to me. They said, ‘Hi, Dakko-chan.’ Dakko-chan was a popular plastic toy that featured a Black girl. When I did not respond, they said, ‘Dakko-chan, would you like to have fun with us?’ I did not know what Dakko-chan meant, but I knew they were making fun of me. They came close to me and said something offensive, so I slapped their faces. Then, they screamed ‘Black’ and ‘prostitute’s child’ at me.”26 Dakko-chan was a popular toy in the 1960s. It had dark skin, full red lips, and big bulging eyes. Dakko means to be hugged in Japanese, implying physical intimacy. We could see that Kozeki’s dark skin is exposed to the erotic desire of the university students through their metaphoric use of Dakko-chan and their insult with the word “prostitute’s child.” Kozeki’s voice tells us that the Japanese associated female dark skin with sexual voluptuousness and low social status.

The problematic social gaze toward dark skin continued in the 1970s with the emergence of a girl’s band that consisted of all Japanese and African American haafu, called Beauty Black Stones. In an article titled “Black Skin Japanese: Four Girls in Ecstasy,” a band member, Kelly, described her experience as follows: “I have known that I am dark and haafu since I was a child. When I went to a public bath with my mother, I could not find where she was. I called her name, but she did not answer me. When I cried, she finally talked to me in a hush. I think she was ashamed of my skin color. When I grew up, I think about love, marriage, and sex, but my dark skin makes me feel gloomy.”27 Kelly’s mother was ashamed of having a dark-skinned daughter, which hurt Kelly. She developed a sense of inferiority and could not think of her relationships or future positively. While the girls of the band talked honestly about their experiences as dark-skinned haafu, they were persistently asked about their sexual experiences by interviewer Tamiki Iguchi. Four girls encouraged themselves that dark-skinned Japanese were human beings and that they needed to fight against prejudice, but Iguchi emphasized their sexual experiences and called their musical ability “Negro’s soul.” He wrote of the stereotypes of dark-skinned women as erotic, tribal, and primitive. He wrote a quite sleazy article, which illustrates the conflicting power struggles between interviewer and interviewees. While four girls internalized the discriminatory Japanese gaze toward dark skin, they tried to overcome it and succeed as musicians. On the other hand, the interviewer slighted their voices and reduced the girls to cheap and erotic objects. From the accounts of Kozeki and Beauty Black Stones as well as scholars’ analysis of dark skin, we see that dark skin is scorned in Japan.

Stephen Murphy-Shigematsu sums up the Japanese problematic attitudes toward skin color as follows: “The Japanese preference of White skin as a standard of beauty, and their prejudice to see the superiority of Caucasian’s physical characteristics and American and Western cultures still remain in Japan. Black skinned Amerasians face harsher prejudice due to their skin color. Their skin is associated with the twisted images that African or African American cultures and races are inferior.”28 Light skin is admired and dark skin is spurned. Are Japanese perceptions of skin color so steadfast?

The representation of dark-skinned women has been gradually changing in contemporary Japanese mass media. Although some Africans and African American entertainers are popular for their outlandish behavior on TV, others achieve popularity for their sophisticated and intellectual deeds. An example of the former is Aja Kong. She is a female wrestler whose mother is Japanese and father is African American. She is popular for her ferocious makeup and violent performance in the wrestling ring. She is an example of the persistent stereotype of Black people as violent and barbaric. On the other hand, singers such as Thelma Aoyama and Chrystal Kay, both Black haafu, are represented as intellectual and sophisticated in the media. Both Aoyama and Chrystal Kay graduated from a very expensive international school and Sophia University, a prestigious Japanese university famous for its bilingual education. Aoyama and Kay’s educational achievements and their fluency in English demonstrate their affluent upbringing and cultural capital. They are successful singers as well. They are not associated with negative stereotypes.

The changing perception toward dark skin has also been reported by mixed race people with Black heritage. Mitzi Carter and Aina Hunter are mixed race Americans with Black and Japanese heritage. They spent a period of time in Japan and reported positive experiences, problematizing the negative treatment of Blackness in academic writings such as that of John Russell. Carter and Hunter write,

There is no doubt the invisible geographies of power that Russell is very conscious of exist and to ignore those is precarious. On the other hand, to also not give credence to the changing image of blackness is just as dangerous. If we have for so long said blacks do not have the means to their representation in Japan, but then dismiss the growing collection of narratives of blacks who have had positive experiences as tourists, temporary workers, or now living permanently in Japan, is to commit the same error that we accuse Japanese of doing—that is, dismissing any blacks as anomalies who or when they speak against the grain of the current models of blackness in Japan.29

Contemporary Japanese perception of skin color does not necessarily associate light skin with superiority and dark skin with inferiority. The experiences of White haafu and non-White haafu are becoming diverse. Murphy-Shigematsu explains that the experiences of haafu differ based on their social capital such as linguistic ability, level of education, social status of parents, and so on.30 These aspects of social capital do not necessarily coincide with skin color. There are non-White people with high social capital and in high social classes. Skin color may coincide with social class, but other factors such as the presence of the father, education, and linguistic abilities seem to determine the social class of haafu in Japan. People with dark skin are therefore not as slighted in Japanese mass media as they used to be, although the fact that non-White people are still exposed to negative social experiences should not be dismissed. If non-White people are more accepted in contemporary Japan, why are non-White female haafu models invisible in Japan’s beauty culture?

Kawaii Culture and the Invisibility of Non-White Female Haafu Models

As indicated earlier, there is a relationship between lightness and kawaii. For example, the haafu cosmetics company Jewerich declares on their home page that their products embody kawaii: “We are a new cosmetics brand with the theme of kawaii. We seek to make products that make the ideal eyes for girls.”31 Many Japanese fashion magazines and cosmetics companies sell products that make Japanese girls look kawaii. According to Inuhiko Yomota, kawaii is a unique notion specific to Japanese culture and difficult to translate into English.32 This article uses the word “kawaii” without translation.

According to Hiroshi Nittono, Japanese female culture is characterized by their fascination with kawaii.33 He writes that Japanese people find kawaii in concepts such as “petit, round, light, white, and transparency.”34 He contends that the feeling of kawaii is derived from the human feeling toward babies.35 Women are more responsive to babies, and kawaii is therefore a more feminine feeling.36 Kawaii objects are loved because of their pretty shape and baby-like nonaggressive behavior. Kawaii is found in the figure of Hello Kitty, produced by the toy company Sanrio.37 Hello Kitty’s real name is Kitty White. She was born in London, and her last name is very suggestive. Many of Sanrio’s products, including My Melody, Little Twin Sisters, Cinnamon Role, and others, have Western roots.

White female haafu models share the traits of kawaii. They are White, are petit, and have big eyes. They are also regarded as infantile and nonaggressive. For example, in an article that analyzes the popularity of White female haafu celebrities and models, Miruo Shima writes, “They behave and talk in a childish manner but it is OK because they are haafu, meaning, they do not understand Japanese culture well. Haafu are not aggressive because they are part-Japanese. On the other side, foreigners are critical of Japanese people. . . . Haafu do not threaten Japanese like foreigners do.”38 A similar analysis can be found in other articles. Tomokazu Takashino writes that “haafu are not smart but they are very friendly.”39 We can see from these articles that Japanese people regard haafu as kawaii because they are infantile and nonthreatening. This is why they dominate Japan’s beauty culture. On the other hand, if kawaii evokes baby-like vulnerability and femininity, then darkness evokes the opposite: aggressiveness and masculinity. This contrast is one of the reasons why non-White female haafu models are invisible—they cannot represent what Japanese women desire.

The fashion and cosmetics industries gain profits by catering to women’s desires. Therefore, they use models who most appeal to the desire of Japanese women: White female haafu models. Non-White female haafu models are invisible because their darkness is not regarded as kawaii and they are not marketable in Japan’s beauty culture. While Japanese women’s desire for kawaii is manifested in the body of White female haafu models, the bodies of non-White female haafu models are suppressed as undesirable.

To summarize, non-White female haafu models may be invisible in Japan’s beauty culture for various reasons. First, non-White female haafu models typically have darker skin. Unfortunately, dark skin is undesirable in Japan’s beauty culture. Second, some do not have the Western female beauty traits that Japanese women admire. Last, some do not fit with kawaii concepts. Japan’s beauty industries need models who have light skin, Western facial features, and kawaii characteristics. If non-White female haafu models want to succeed in Japan’s fashion and cosmetics industries, they have to be kawaii. Unlike non-White female haafu models, White female haafu models are located at the intersection of transnational lovely White ideology and local kawaii ideology, on which the beauty industries can profit. Therefore, White female haafu models dominate Japan’s beauty culture.

The hypervisibility of White female haafu has created the stereotype of haafu as kawaii, light, and Western. Non-White haafu are marginalized, reduced to non-kawaii status. They may feel inferior toward their own skin, non-Caucasian facial features, and cultural backgrounds. For example, a haafu who is in her twenties and whose mother is Thai and father is Japanese comments on her troubled feelings toward the haafu stereotype: “Most haafu in the media are Western haafu. . . . Western haafu are very pretty and attractive. Japanese people associate haafu with Western haafu. When I tell people I’m haafu, people are surprised. I’d like to say that anyone whose parents’ nationalities are different is haafu, but I had inferiority of not looking like a pretty Western haafu. I one time wished to have an American mother so I could look different.”40 Her comments illustrate the association of haafu with kawaii and Caucasian facial features, and her incompatibility with these traits. The hypervisibility of White haafu gives non-White haafu a sense of inferiority because they feel excluded. Changing the representation of haafu in the media may be a way to overcome these feelings of inferiority. Especially for girls, the influence of beauty culture is huge. If it had more non-White haafu models, non-White haafu would be more confident in self-proclaiming that they are haafu too. This would contribute to challenging the stereotype of haafu and to exposing the reality of haafu, who are racially and ethnically diverse. How could the invisibility of non-White female haafu models be overcome?

Their invisibility is derived, as we have seen, partly from their relationship to the concept of kawaii. Kawaii does not contain darkness. According to Nittono, however, what Japanese people find kawaii has changed with time: “Even the same generation of women find different objects kawaii. Fashion magazines redefine the meaning of kawaii one after another.”41 In short, there is a possibility that non-White female haafu models would be regarded as kawaii. If Japanese culture embraced darkness as kawaii, non-White female haafu models might be more visible in fashion magazines and the cosmetics industry. Yet, is it an ideal situation for them?

Kawaii is a unique cultural concept in Japan, but it is far from uncontroversial. For example, feminist scholar Chizuko Ueno points out that kawaii is a strategy for Japanese women to be loved and protected by men. Kawaii derives from baby’s nonaggressive behaviors. The vulnerability of a baby evokes people’s instinct to protect babies. Ueno contends that Japanese men are looking for a kawaii partner who satisfies their chauvinism. To respond to the men’s desires, Japanese women strive to be kawaii. If they threaten men’s chauvinism, they will not be loved by men. To be kawaii thus means to be nonthreatening to men’s authority. Since women subject themselves to the desire of men by internalizing kawaii ideology, Ueno argues that kawaii puts women in a subservient second-class status made by a patriarchal society.42 In short, as long as women try to be kawaii, they will be reduced to the subservient status desired by men. Under the dictates of kawaii ideology, Japanese women avoid non-kawaii traits such as darkness, aggressiveness, voluptuousness, and so on. Non-White female haafu models may embody these non-kawaii features, which have no market value in Japan. This may be a reason for their invisibility in Japan’s beauty culture. Is there a possibility that Japan’s beauty culture will accommodate non-White haafu female models who are incompatible with lovely White and kawaii ideology?

Conclusion

The Japanese fashion and cosmetics industries have used many White female haafu models, reflecting Japanese women’s desire for light skin, Caucasian facial features, and kawaii. Non-White female haafu models are excluded from Japanese beauty culture because they do not have the qualities Japanese women desire. Their invisibility may be positively understood as their resistance to the lovely White and kawaii ideology. However, as long as they are invisible, their very existence is not acknowledged by Japanese society, negatively affecting their self-esteem.

As stated earlier, the Japan’s 2015 Miss Universe contestant is Ariana Miyamoto. Although Miyamoto may have Western beauty, her dark skin counters kawaii ideology. Miyamoto’s selection may be quite significant in changing the direction of female beauty in Japan because she proves that non-White haafu can represent Japan’s female beauty. It may be difficult to create a new standard of beauty, completely free from the long-dominant lovely White ideology and kawaii, but with the circulation of diverse female representations, non-White haafu female models could become more visible in Japan’s beauty culture.

Japan is often regarded as a racially and ethnically homogeneous nation, yet with the increasing rate of intermarriage, the haafu population is growing. The number of haafu has not been researched by any official institutions, so their population has to be inferred through the number of internationally married couples, whose children supposedly are haafu. According to Japan’s National Institute of Population and Social Security Research, the number of international marriages was 21,448 in 2013.43 Many of these couples are non-Japanese Asians married to Japanese (e.g., 39.8 percent of Japanese women married Chinese or Korean men; 58.2 percent of Japanese men married Chinese or Korean women).44 From the statistics, it can be surmised that many haafu are people with non-White heritages. Yet the mass media overwhelmingly represent White haafu, which does not reflect the racial/ethnic diversity of haafu. To overcome the invisibility of non-White haafu in beauty culture, it would be important for non-White haafu female models to appear more frequently in fashion magazines and in the cosmetics industry’s advertisements, which could gradually change Japanese consciousness of race and ethnicity. Their very existence in beauty culture could challenge the lovely White and kawaii ideology that is rampant in Japan, and could lead to the creation of an alternative female beauty, enabling all women to be proud of who they are regardless of skin color and facial features.

Notes

1. Baye McNeil, “Meeting Miss Universe Japan, the Half Who Has It All,” Japan Times, April 19, 2015, http://www.japantimes.co.jp/community/2015/04/19/general/meeting-miss-universe-japan.

2. This chapter roughly defines race as certain physical traits and ethnicity as cultural membership, but both are socially constructed concepts and are changeable with time and place.

3. Itsuko Kamoto, Kokusaikekkon Ron? [A theory on international marriage?] (Kyoto: Horitsu Bunkasha, 2008), 150–151.

4. Natalie Maya Miller and Marcia Yumi Lise, The Hafu Project (Japan: Hafu Project, 2010), 3.

5. Paul Spickard, Mixed Blood: Intermarriage and Ethnic Identity in Twentieth-Century America (Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1989),153.

6. Stephen Murphy-Shigematsu, Amerajian no Kodomotachi: Shirarezaru Mainority Mondai [Amerasian children: Unknown minority problems], trans. Junko Sakai (Tokyo: Shueisha, 2002), 101.

7. “Geinoukai wo Sekkensuru haafu Bijo” [Haafu beauties dominating show business], Flash (May 8, 2007): 29.

8. Hiro Endo, “Cool & Exotic: Haafu Girls Boom!” (May 30, 2007), http://allabout.co.jp/gm/gc/2027661.

9. This essay uses the terms “White” and “non-White” to express skin colors. These skin color classifications sometimes coincide with racial categories and/or geography. Whites are Caucasians. Blacks are people with African heritage. Browns are people with dark skin, but not as dark as Black people. Similar to the definitions of race and ethnicity, these color categories are also socially constructed concepts and are changeable with time and place.

10. Runway (September 29, 2012).

11. Superheadz, Life as a Golden Half (Tokyo: Powershovel, 2007), cover.

12. “Haafu Face Recipe,” Bea’s UP (December 1, 2009): 52.

13. Ibid., 52.

14. Hiroshi Wagatsuma and Toshinao Yoneyama, Henken no Kouzou: Nihonjin no Jinshukan [A structure of prejudice: Japanese racial views] (Tokyo: NHK Books, 1967), 20.

15. Ibid., 68.

16. Ibid., 26.

17. Ibid., 67.

18. Ibid., 37.

19. Joanne L. Rondilla and Paul Spickard, Is Lighter Better? Skin-Tone Discrimination among Asian Americans (Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield, 2007).

20. Wendy Chapkis, Beauty Secrets: Women and the Politics of Appearance (Boston: South End, 1986), 37.

21. Julie Matthews, “Eurasian Persuasions: Mixed Race, Performativity and Cosmopolitanism,” Journal of Intercultural Studies28.1 (2007): 50.

22. Wagatsuma and Yoneyama, Henken no Kouzou, 89.

23. John Russell, Nihonjin no Kokujinkan: Mondai ha Chibikuro Sambo dakedehanai [Japanese perception of Black people: A problem is not only Chibikuro Sambo] (Tokyo: Shinhyoron, 1991), 4.

24. Wagatsuma and Yoneyama, Henken no Kouzou, 99.

25. Atsuhisa Yamamoto, “Haafu no Shintai Hyyosho ni okeru Danseisei to Jinshuka no Politics” [Masculinity on the physical representation of haafu and the politics of racialization] in Haafu to ha dareka: Jinshu Konko, Media hyoushou, koushou jissen [Who is haafu? Race mixture, media representation, negotiation], ed. Koichi Iwabuchi (Tokyo: Seikyuu, 2014), 114.

26. Keiko Kozeki, Nihonnjinn Keiko: Aru Konketuji no Shuki [Japanese Keiko: A memoir of a racially mixed girl] (Tokyo: Horupu, 1980), 59.

27. Tamiki Iguchi, “Kuroi Hada no Nihonjin: Yonin Musume ga Moetagiru Toki” [Black skin Japanese: Four girls in ecstasy], Shukan Post (February 17, 1972): 168–172.

28. Stephen Murphy-Shigematsu, Amerajian no Kodomotachi: Shirarezaru Mainority Mondai [Amerasian children: Unknown minority problems], trans. Junko Sakai (Tokyo: Shueisha, 2002), 95.

29. Mitzi Carter and Aina Hunter, “A Critical Review of Academic Perspectives of Blackness in Japan,” in Multiculturalism in the New Japan: Crossing the Boundaries Within, ed. Nelson Graburn, John Ertl, and Kenji Tierney (New York: Berghahn Books, 2008), 197.

30. Stephen Murphy-Shigematsu, When Half Is Whole: Multiethnic Asian American Identities (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2012), 129.

32. Inuhiko Yomota, Kawaii Ron [Kawaii theory] (Tokyo: Chikuma Shinsho, 2006), 38.

33. Hiroshi Nittono, “Kawaii ni taisuru Koudoukagakuteki Apurochi” [A behavioral science approach to kawaii], Ningenkagaku Kenkyu 4 (2009): 19.

34. Ibid., 24.

35. Ibid., 29.

36. Ibid., 26.

37. Yomota, Kawaii Ron, 16.

38. Miruo Shima, “Haafu Tarento tairyo hassei no Naze” [Why are there so many haafu celebrities in show business?], February 14, 2012, http://news.livedoor.com/article/detail/6277751/.

39. Tomokazu Takashino, “Miwaku no Haagu Bijo Juukunin” [Nineteen exotic haafu beauties], Playboy (December 19, 2011): 6.

40. Koichi Iwabuchi, “Haafu toiu Category nikansuru Toujisha heno Kikitorichosa” [An interview with haafu on the category of haafu], in Iwabuchi, Haafu to ha dareka, 269–270.

41. Nittono, “Kawaii ni taisuru Koudoukagakuteki Apurochi,” 29.

42. Chizuko Ueno, Oiru Junbi [Prepare to be old] (Tokyo: Gakuyo Shobo, 2005), 27–28.

43. National Institute of Population and Social Security Research, Jinko no Doko: Nihon to Sekai Jinkoutoukei Shiryoshu 2015 [Demography trend: Japan and the world 2015] (Tokyo: Kosekitokei Kyokai, 2015), 105.

44. Ibid., 106.