11

Checking “Other” Twice

Transnational Dual Minorities

Lily Anne Y. Welty Tamai

The cover of the November 12, 1953, issue of Jet Magazine asks in the title, “Do Japanese Women Make Better Wives?” Underneath the headline is a photograph of an interracially married couple, James and Teruko Miller. James Miller is Black and wears a military uniform and Teruko Miller is Japanese and wears a high-collared white blouse, and they both directly face the camera (see figure 11.1). The cover’s subtext reads, “Indianapolis couple has found happily married life since wedding three years ago in Japan.”1 We can surmise that the magazine issue was intended to address the question of postwar interracial marriage of Black soldiers to Japanese women to the primarily Black readership of Jet Magazine. Why did they choose a Japanese woman to represent an ideal partner for Black men? Was the article inferring that perhaps Japanese women made better wives than Black women? Who were the mixed race children born to couples like James and Teruko?

Mixed race people born at the end of World War II made history quietly with their families and their communities. Wars and the military occupations that followed, coupled with increased migration across the Pacific, created a surge of interracial relationships, resulting in a midcentury multiracial baby boom. Easily identifiable by their mixed race features, they were the children of the enemy: in Japan they symbolized defeat and racial impurity, while in America they were seen as an extension of America’s democratic intervention abroad and a symbol of the salvation that the United States offered Japan during the postwar occupation.2 Their family lives varied. Some grew up with one or both of their biological parents, others were raised by extended family members. Due to choices made by their parents and policies instituted by states, many were left stateless, orphaned, raised by single mothers or by adoptive families. These multiracial American Japanese ushered in the legacy of transnational adoption and immigration of children from Asia. Their baby pictures peppered the postwar newspapers and magazines in Japan and the United States ranging from Life, Ebony, and Jet to Asahi Gurafu.3 The variety of the children’s backgrounds reflected the military’s microcosm of American racial diversity.

This chapter focuses on the lesser known narratives of mixed race American Japanese who are dual minorities while highlighting the way in which communities of color helped influence these mixed race families. Some dual minorities had fathers who were Black, Latino, or Native American. Some grew up and remained in Japan or in Okinawa, while others came to the United States as young adults. Hundreds came as infants or young children and were adopted into American families. Leaving Japan to cross the Pacific Ocean meant arriving in their father’s land to deal with a new set of rules surrounding race and the flux of a migrating identity. The stories span families, decades, time, and the Pacific. I connect the importance of oral history methodology with transpacific border crossing to address the issues of mixed race transnational adoption, migration, and marriage.

I examine both chronologically and thematically the ways in which the multiracial perspectives of dual minorities from two minority groups expand our understanding of the Japanese American community. The title of this chapter is a play on the selection of race boxes on official forms and documents, whereby dual-minority individuals might choose “other” twice. It refers to mixed race people whose racial background comes from parents who are both from two different minority ethnic groups. Upon further investigation, we gain new perspectives on the postwar mixed race experience. Specifically, I argue how interracial communities, families, and mixed race individuals challenged the default narrative of White normativity in the US military and in the postwar period, while also expanding our understanding of the transnational Black Pacific, or the diaspora of Blacks in the Pacific Rim. Using a variety of sources, including oral history interviews, autobiographies, archival material, magazines, and secondary sources, this chapter showcases the experiences of dual minorities within the context of a transnational community.

Decentering Whiteness through the Black Pacific

Decentering Whiteness requires intentionally searching for sources that provide a fuller history. In this chapter I showcase how the soft power of cartoons silenced images of Blacks by not including them. Moving beyond the mainstream story takes deliberate work because not only are the experiences of dual-minority mixed race individuals not prominent, but also the histories of their parents are often absent. However, within the context of mixed race studies, the experience of White-Japanese multiracials is a well-established narrative in the Pacific and in the United States.4 Early on, scholars who focused on topics of mixed race Japanese individuals led the scholarship by including the voices of dual minorities.5 From those stories of non-White mixed race individuals, we begin to uncover more about their parents and the historical circumstances which prevailed. If there were mixed race individuals who were Native American and Okinawan, Mexican and Okinawan, Black and Japanese, among other ethnic mixes, it is clear that the military was more ethnically diverse than presented in historical photos and books. In fact, numerous minorities served in the military, in addition to the individuals who served in segregated units, and we know this because of the backgrounds of the children. Interracially married couples and their children help to demonstrate the complexity of dual minorities and their place within migrant communities. This chapter contests the hegemony of Whiteness and its central position in our historical understanding of the post–World War II mixed race experience by examining mixed race migrant military communities through the lens of the transnational Black Pacific.

Postwar interracial couples and their communities were no different from the many mixed race families who crossed the Pacific before them. This chapter frames the postwar families within the historical context of mixed race communities beginning with immigrant Japanese groups who settled in the territory of Hawai‘i and on the West Coast of the United States. Examining the early multiracial communities contextualizes their histories within the racial discourse.6 Dual-minority individuals operated in a hybrid space that was layered with complex family histories. Examining multiracial communities also helps to build upon the scholarship of passing, which often privileges the narrative of White normativity.7 It becomes evident that when given a choice, mixed race individuals did not always choose to be White. Unpacking the history of the pre–World War II mixed race Japanese communities sets the stage for the postwar communities and the racial climate that couples like James and Teruko Miller might have experienced.

Historicizing Mixed Race Communities

In the late nineteenth century, the first Japanese American families to settle in Hawai‘i and the United States were interracial families with mixed race children.8 These lesser known mixed race communities in the Japanese American context include the Gannenmono in the Kingdom of Hawai‘i in 1868, the Wakamatsu Tea and Silk Farm Colony in Placerville, California, in 1869, and the first Japanese community outside of Portland in Multnomah County, which created the township of Orient, Oregon, in 1880. The first Japanese community that settled permanently came to the Kingdom of Hawai‘i in 1868.9 Like many sojourning immigrants, the majority of them were male laborers intending to stay briefly, earn money, and return to Japan as rich men. From the initial 153 laborers, only a handful remained and established families. Those who stayed married local Hawaiian women, created mixed families, and became the first Japanese settlers by remaining permanently in the community (see figure 11.2).10

Figure 11.2. Gannenmono Matsugoro Kuwata with his Hawaiian wife Meleana and family, circa 1899. They were the first Japanese American family to settle in Hawai’i. Kuwata was among the first of 153 laborers to leave Japan for Honolulu in 1868. Source: Bishop Museum, Honolulu, Hawai’i, NRC.1998.66.29.

The initial group from Japan who established roots on the US mainland were the members of the Wakamatsu Colony in Placerville, who arrived in San Francisco on May 20, 1869. With them they brought twenty thousand mulberry bushes and six million tea seeds with the intention of creating an agricultural community producing silk by settling and raising silkworms, which eat the leaves of the mulberry plant. Many of those initial pioneers returned to Japan after two years when the colony failed economically. However, among the few who stayed was Kuninosuke Masumizu (1849–1915), who married Carrie Wilson, the mixed race daughter of a Blackfoot Indian woman and a former Black slave. Their descendants, the Elebeck family, identify as African American and are aware of their mixed Japanese ancestry. In Gresham, Oregon, the first pioneering family from Japan who settled in 1880 was Miyo Iwakoshi and her Australian Scottish husband, Andrew McKinnon. They established a sawmill in East Multnomah County, and McKinnon named the township Orient after his wife. This European and Japanese family illustrates that the first family in Oregon also had mixed roots.11

These community studies reveal how circumstances like economics, opportunities, and wars resulted in the immigration of people to and from the United States.12 The movement of people across the Pacific is more complicated than just push-and-pull factors between Asia and the Americas. The factors are not static. Economics, population decline, immigration legislation, wars, and a web of global industrial capital factored into the ebb and flow. The communities that sprang up as a result of interracial relationships and mixed race progeny did so because circumstances were favorable. The one-drop rule of hypodescent that operated to reinforce the master class and oppress the slave class did not always apply in cases with dual minorities because the racial hierarchy and ethnic landscape were simply different in the Pacific Rim.

Like the descendents of the initial Japanese American communities, mixed race individuals who are dual minorities force people to reconsider existing categories of race and mixed race. The scholarship that examines dual minorities in mixed race communities in greater detail includes Karen Leonard’s Making Ethnic Choices, which examines mixed race Punjabi Mexicans in the Imperial Valley, and Rudy P. Guevarra Jr.’s Becoming Mexipino, on mixed race Mexican and Filipinos in San Diego.13 For both Punjabi Mexicans and Mexipinos, one or both parents were immigrants and the children were dual minorities of Asian descent who were US citizens. Neither the Punjabi Mexicans nor the Mexipinos fit within the established Black-White binary but rather added additional layers by expanding and complicating our understanding of racial, marital, and religious diversity within dual mixed race communities.

Some mixed race American Japanese communities in the postwar context are families created by the military-industrial complex. Analogous to the migrant laborers to the United States, deployed military personnel and their families are also migrant laborers who created a racially mixed community within a militarized borderland on the US military bases. In Teresa Williams-León’s study on mixed race military communities in Japan during the 1980s, very much like the aforementioned early mixed-race communities, we can see similar reasons for immigration and transpacific border crossing. For these families, labor and economics with the additional reason of military necessity catalyzed the immigration of this migrant labor force.14 Especially following World War II and the American occupation of Japan, US military bases have been a mainstay in Japan and Okinawa, creating decades of hybrid and third-space communities of interracial families and mixed race children. New families enter when they have PCS (permanent change of station) orders to relocate to another duty location that may change from year to year, or every four years. Those communities have racial, cultural, and linguistic fluidity despite the electrified fences and limited access of the military bases. And much like the migrant mixed race families, they too experienced a process of acculturation.

Model Minority Wife

In “Do Japanese Women Make Better Wives?” Jet Magazine positioned Japanese women as model wives in contrast to what we can infer as Black women. There are parallels in the tone between this article and the William Petersen article, “Success Story, Japanese-American Style,” published in New York Times Magazine in 1966.15 Petersen’s article set into motion debates about Asian Americans, specifically Japanese Americans, as model minorities who achieved success in the United States despite barriers of racial discrimination. Combined, these texts perpetuate what I call the “model minority wife.” The Jet Magazine article’s framing of the argument that Japanese women might serve as model wives to Black men minimizes the position of Black women, if they choose not to think what their husbands wanted them to think. In short, Jet Magazine undermined Black womanhood. The article pits Japanese women against Black women, and indirectly blames Black wives for not being the model minority wife, much like Petersen’s article praised Japanese Americans for being model minorities while questioning why Blacks did not achieve the same level of social and economic success.

Along with the Millers from the epigraph, another couple mentioned in the article, Bruce and Sayako Smith, reflect on their relationship as an African American husband and Japanese wife. Bruce states, “I like it when my wife waits on me hand and foot, gives me a massage when I come home from work, washes my back in hot water and turns down the bed so I can take a nap before dinner.” Sayako responds, “I feel it is my duty to do my husband’s bidding, . . . and if this makes me different from American women, then I don’t know what to do about it because acting this way makes him happy. If he’s happy, I am happy.” The article continues, “As in her homeland, she [Sayako] regards her husband as No. 1 and herself as No. 2. Or as Mrs. Smith explains, ‘I think only what I think Bruce wants me to think.’”16 The Smiths and the Millers are two examples of families that have particularly defined gender roles as husband and wife. Do Japanese women make better wives when they take on a subordinate role within their marital relationship? Are Japanese wives better because they adapt to new relationships?

What is missing from this article is how these families actually functioned within the larger military communities, and specifically the Black military community. In reality, Black women were instrumental in helping Japanese women who were married to Black men get their bearings as new Americans in the United States. Japanese war brides who married Black soldiers acculturated to the new environment, learned how to be Americans, and navigated their households via the experiences of the Black community, not necessarily the White community. Interracially married couples who were in the military formed communities among themselves within the Black community both on and off the military base. For example, Curtiss Takada Rooks’s parents met and married while his father served in the US Air Force in Japan. Although she was married to an African American man, Curtiss’s Japanese mother learned how to be an American woman from Black women within the military community. Within the process of mastering American ways, many Japanese women learned how to be Black women first. Curtiss’s mother learned how to cook many dishes typically served in Black households, and she established relationships by singing in the choir in their Baptist church.17 According to Jet Magazine, the model wife might have been cast as a Japanese woman, however, it was Black women who modeled the behavior of Americans for Japanese women.18

Babysan’s Soft Power

While Jet Magazine brought to light the experiences of Japanese women who were married to African Americans, another source from the period erased the presence of African American GIs entirely through the soft power of cartoon images. Bill Hume (1916–2009), a Navy reservist and cartoonist for the Stars and Stripes (the newspaper for the armed forces), published several illustrated paperback collections of his weekly comic strip, Babysan, following World War II (see figure 11.3).19 Wildly popular, his books functioned as cultural guidebooks that explained the day-to-day incongruencies of Japanese customs to American GIs who had served in occupied Japan. His main character, Babysan, was a bright and lively Japanese woman who had many GI boyfriends and spoke like a fortune cookie. She wore tight-fitting shirts that revealed ample cleavage along with pencil skirts and geta, Japanese wooden clogs. Her hair bounced like that of a 1950s pinup model. The different scenarios in the books illustrate the hows and whys of the way Japanese culture might confuse the Americans occupying the country. In some settings she is talking to a group of American GIs, while in other settings she is having a conversation with one man. The men are always in their military uniforms, and they are always White.20

Figure 11.3. Bill Hume, Babysan’s World: The Hume’n Slant on Japan (Rutland, VT: Charles E. Tuttle Co, 1959).

Part of the imagery within the exchange of cultural ideas of Americans in occupied Japan had to do with Bill Hume’s depictions. The Babysan cartoons reinforced White normativity in the military. Hume colored the imaginations of a generation of soldiers through his cartoons. Seasoned servicemen in Japan could identify their own intimate relationships with Japanese women in the cartoons, and newly deployed servicemen learned about the culture of dating Japanese women. The reach of the books was broad, and their soft power was influential. The books were so popular that the publisher, Charles E. Tuttle Co., reprinted Hume’s three books over a dozen times each, and in 1965 Babysan’s World: The Hume’n Slant on Japan went into its twenty-fifth printing.

Hume’s books were two-sided. On one hand, Hume took great care to explain particular aspects of Japanese society to confused Americans who had very little exposure to the idiosyncrasies of foreign mores. On the other hand, he sexualized Japanese women, omitted Black soldiers, reduced Japanese people to Asian caricatures, and made Japanese men a part of the scenery. As argued by historian Isaiah Walker, to sexualize the female and erase the male is a colonizing move.21 Not only does this operate to reinforce colonialism, it also functions to center Whites via the erasure of Black and Japanese men. Babysan was an amalgamation of Japanese women in the mind of Bill Hume. Although the Babysan books discussed cultural questions and issues relating to interracial dating, Babysan was cast not as a future wife, but as a temporary girlfriend. As stated by Hume, “Babysan was a poor man’s geisha.”22 But in fact, she was portrayed only as a White man’s geisha.

Certainly, we can surmise that Hume did not include African American GIs in his cartoons because he was in a unit with only White men and the Black soldiers were in segregated units. However, Black men were part of the military and read the Stars and Stripes. Based on interviews, we know that Japanese women remarked that Black men were nicer to them than White men were.23 Many Black soldiers dated and married Japanese women, and fathered mixed race children who were born during the US occupation of Japan and Okinawa. Black GIs and their children formed part of the transnational Pacific diaspora.24

Transnational Black Pacific

Concepts like the Atlantic World and the Black Atlantic engage regions that have connections and histories illustrating their relationship with Europe. Defined as the interaction of people within the empires that have bordered the Atlantic Ocean rim since the 1450s, the orientation of Atlantic World emphasizes the relationship to Europe. The Black Atlantic refers to the diaspora and culture of Blacks across the Atlantic World and into the Americas and the Caribbean.25 Within that relationship exists an exchange of people, products, and culture that reinforces the metropole to the center, where the origins are often defined as European.

The Black Pacific refers to the consciousness of Blacks, their diaspora, and the connection to Asia via the Pacific Rim. The transatlantic slave trade and the forced removal of people from sub-Saharan Africa resulted in a wave of people of African descent mostly into the Americas. The Black Pacific parallels the Black Atlantic without the forced removal of people, but it includes the conscripted and voluntary military service of African Americans from the nineteenth century to the present in Asian nations. US military intervention in Asia and the Pacific has been a driving force for African Americans to cross the Pacific since the Spanish-American War.26 Studies that center on the Pacific also work to decenter the Black-White binary because they must contend with Asia, thereby expanding our understanding of the changing and static dynamics of race and racism as well as existing social hierarchies. Other terms that emphasize the Black contribution specifically to Japan include Black Japan and Black Okinawa.27 This chapter centers the narrative of Black Pacific by including the voices and stories of mixed race people and their parents who complicate this transpacific and transnational history.

Mixed race individuals and their families functioned within a transnational framework in the Pacific. The term “transnational” is defined as something that operates between and beyond national boundaries. However, the definition is more complicated than just border crossing or a company that has an office overseas. Transnational mixed race individuals need to be contextualized within their families and the larger global migration of labor, economics, capital, and colonialism.28 Moreover, the US military is not only transnational but also global.29 It operates globally in the name of democracy and defense within a sphere of colonialism. Service members are the migrant labor force who support the aims of the US government. The military fosters interracial relationships, which in turn create mixed race people. Their families transport culture back and forth between a transnational militarized borderland and the local community. As stated by Fernando Herrera Lima, “Transnational families are therefore vehicles—better yet, agents—for both material exchanges and the creation, re-creation and transformation of cultures.”30 Within this larger transnational framework, mixed race dual minorities must navigate being a person of color while also being a mixed race person of Asian descent. Sometimes this also includes an additional layer of identity as a transnational adoptee.

The postwar transnational adoption boom from East Asia to the United States began with a mixed race Black Japanese baby. Born in 1947, Demitoriasu, who later took on the name Damien, was also the first mixed race Black Japanese baby to come to the Elizabeth Saunders Home for Mixed-Blood Children. In fact, his adoption required an act of Congress for him to be able to enter the United States.31 Miki Sawada, who was the headmistress of the Elizabeth Saunders Home, recalled the first mixed race Black and Japanese child who came to the orphanage:

There was a boy named Deme chan. He was the first Black child that came to the Saunders Home. Underneath his long eyelashes were these big eyes that sparkled with intelligence. He struck me as a sociable and friendly child who was just starting to walk—by grabbing on to things and walking sideways. He wasn’t the kind of kid to go and look for his parents, but maybe that was because he had not spent that much time with his birth mother. On his family register in the column that denotes the birthfather’s whereabouts, it was written only as “unknown.”

At first we were calling him Demitoriasu (English pronunciation: Demetrius), but sometime later we started using the term of endearment of Deme chan and called him that.32 For us [at the ESH] this was the first Black child and although we were particularly careful with him, he had no ill feelings, no cares or worries, and every day we raised him, he slept well and he ate well.33

His adoptive parents, the Tillman family, were a Black couple who were stationed in Japan while serving in the Air Force. They also adopted a mixed race Black Okinawan girl who became Damien’s younger sibling.34 Not only White families, but also Black families were actively adopting mixed race children from Japan.35 Although the Tillmans had secured the adoption paperwork, due to the immigration laws restricting Asian immigration to the United States prior to the 1965 Immigration Act, they could not bring a baby from Japan, even if he was mixed race and had an American parent. Miki Sawada wrote to Congressperson Walter Judd from Minnesota to assist mixed race children with their immigration paperwork and to somehow bypass the legal restrictions. After much delay, her request was granted and Deme chan became the first mixed race transnational adoptee who immigrated to the United States, establishing a precedent for postwar adoptees from Asia.

While Black soldiers migrated west across the Pacific, some of their mixed race children migrated east to the United States as children and as adults in the decades following World War II. Keiko was born in 1947 in Sasebo, Nagasaki prefecture, to a Japanese mother and an African American father. In Sasebo, she had a difficult time growing up as Black and Japanese and spent a lot of time defending herself in fights with the neighborhood children.36 When she was twenty years old, she married an African American man and came to the San Francisco Bay Area, where she has lived for over forty years (see figure 11.4).

Figure 11.4. Kassy and Keiko. Source: Era Bell Thompson, “Happy Ending: Grown-Up Brown Baby Finds Husband in Japan, a Home in the USA,” Ebony (July 1968): 66.

After moving from Tokyo in 1967, Keiko and her family settled in the South Bay. She and her husband were married at a Japanese Christian Church, where they, among many Japanese Americans, are still members of the congregation. When Keiko’s family had the opportunity to move north to Oakland, she recalled that she wanted to stay geographically closer to the Japanese American community rather than move where there was a greater concentration of African Americans. Her cultural home existed among the Japanese American community, and moving to a locale where African Americans lived was not necessarily a better fit for her. Keiko’s decision to remain near the established Japanese American community illustrates how her choice challenges the narrative of the Black-White binary.

Nearly every year as an adult Keiko returns to visit her family in Japan, and inevitably she experiences microaggressions during those visits. Even though others assume from her appearance that she is foreign—and by default not Japanese—Keiko asserts her Japaneseness and decides what personal information she will share. When Keiko is complimented on her Japanese speech, local individuals remark, “Your Japanese is so good!” Keiko replies with, “Thank you. I’ve been to Japan a few times before.” Clearly, Keiko positions herself in a way where she retains agency by not having to provide personal reasoning for her language ability, and also evades having to explain why her presumed foreign appearance and her native speech align.

Dual-minority individuals were not immune to shifts in racial formation, especially across borders. These racial encounters were situational and changed depending on age and historical period, illustrating the social constructed nature of race. Fredrick was born in postwar Japan to a Japanese mother and a Black father. He and his family moved to the United States when he was twelve years old. Fredrick and his mother spoke Japanese to each other, and coming to the States was a big change. On his blog he shared his experience as a mixed race person: “For me, in New Mexico, I got ‘nigger’ and ‘Jap’ and ‘Gook’ as well as ‘Slant-eye’ ‘Fu-Manchu’ and other comments and names about my being mixed-up, confused, impure. Later, primarily in the late 1960s into the 1970s, this turned to ‘exotic’ and ‘you have beautiful skin.’ Not as painful, but just as lonely (since I was not there but as a figure of their own racialized notions of people).”37 Fredrick did not change anything about himself, but the way others perceived his racial identity was in flux over several decades.

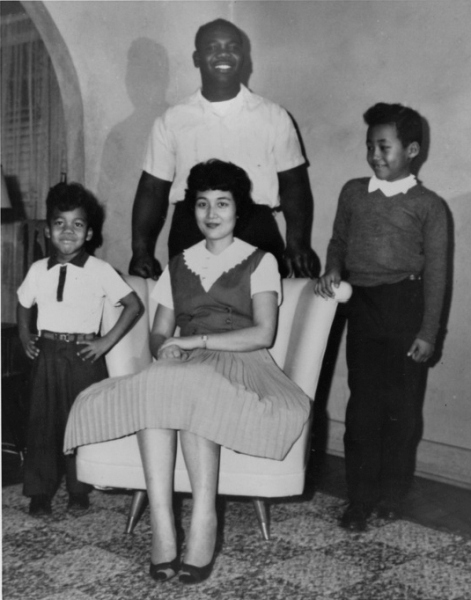

The people who reinforced ethnic pride and defended dual minorities were not always from that same ethnic group. Curtiss was born to a Japanese mother and an African American father. His father was from North Carolina and came of age in postwar Japan where he served in the military. Japan was a place where Curtiss’s father had status as a Black man, unlike in the South or other working-class places. Their family lived on military bases from Okinawa to Kansas. As a kid, Curtiss recalled using the term “gook” as a way to tease Asians. When his father got wind of this, he immediately corrected his son, reminding him, “You are gook. Your mother is a gook. Don’t ever use that word again.”38 Curtiss’s pride about being Japanese was fostered not only by his Japanese mother, but also by his African American father (see figure 11.5).

Black women helped Curtiss’s mother get accustomed to the United States. As a result, her influence as a Japanese mother in the Rooks household expanded to include African American sensibilities. Curtiss recalled that his mother was involved in the women’s choir at their Black Baptist church and had a circle of friends who were Black women from within the military community. He reflected on his family’s food culture: “Perhaps the most fun mixture of culture came at the kitchen table. Gohan with every meal, turnip or mustard greens cooked slowly on Sunday afternoon, sweet potato pie at holidays, octopus or squid to freak out my Midwestern high school friends, and of course teriyaki chit’lins made our family cuisine our own.”39 To outsiders it may appear as a hybrid culture, but to their family, and many other families like theirs, this was the norm.

A transnational identity is complex and not devoid of misunderstandings by others. Elizabeth was born and raised in Okinawa and came to the United States to attend college. Her mother is Okinawan and her father is Black, and they met while her father was serving in the military in Okinawa. She has two half sisters, one who is Okinawan and Filipino, the other Okinawan and Puerto Rican. Elizabeth did not grow up with her father, and although she knew her biological mother, as an infant a childless couple unofficially adopted her. She often visited with her biological mother, but they never lived in the same household together. During college in Minnesota she met her future husband, an Ethiopian man who had fled persecution in his home country. After graduating from college in the United States, the two started their own family and made their home in mainland Japan. She remarked about her own identity and ethnic choices: “I wanted my children to know that they look like their parents.”40 Her children are bilingual in English and in Japanese. Although Elizabeth’s background was clear to her, other people had difficulty understanding her mixed race background and cultural transnationalism.

The linguistic diversity in the transnational Black Pacific includes native English speakers, but also individuals for whom neither English nor Japanese is their first language. Saeko’s father, who was an African American man from New York, had served in the US military in Okinawa, where he met her Okinawan mother. Saeko grew up in Okinawa and, along with Japanese, she was raised speaking Uchinaguchi, the indigenous language of Okinawa. “I am told that I am more Uchinaa than most people in Okinawa, even though I am only half. My heart is Okinawan.”41 Similar to Keiko’s experience, locals in Okinawa praised Saeko because of her ability to speak Japanese, despite the fact that she has lived there all of her life, and knows only limited English. Based on her appearance, they expect her to be a foreigner, or someone who is currently serving duty on one of the military bases in Okinawa. As one would presume, it is exhausting (and bordering on offensive) to be reminded of a perceived linguistic and physical dissonance. Saeko repeats the same thing during these encounters: she is Okinawan, born and raised on the island, and has the linguistic authenticity as a native speaker of Uchinaguchi. Language is intimately tied to identity, and on a larger scale, the languages that are connected to dual-minority identities have many layers of meaning, despite appearing to be muted because of their mixed race phenotype.

Figure 11.5. The Rooks family, Manhattan, Kansas, ca. 1961. Courtesy of Curtiss Takada Rooks.

Conclusion

Decentering Whiteness takes work. It requires examining the default narrative of White normativity, dismantling White hegemony by considering coexisting narratives that are often marginalized or untold. Challenging White hegemony includes expanding upon macro-level concepts like the Black Atlantic, by looking at Asia west across the Black Pacific to the Pacific Rim. In the search for these stories, it is apparent that there are gaps in the sources when it comes to the topic of dual minorities and their families.

This chapter has framed the stories of mixed race dual minorities in the context of other historic mixed race families, illustrating how their experiences are not all that rare. Postwar intermarried couples like James and Teruko Miller were neither new nor revolutionary. There may have been only a few couples in their local communities who looked like the Millers, however when contextualized historically, much like the Gannenmono, the Millers are the modern example of people crisscrossing the Pacific, expanding the notion of the Black Pacific, and challenging White normativity. Their mixed race children mirrored the experiences of Punjabi Mexicans and Mexipinos, and pushed boundaries of race and community too. By placing mixed race people like Damien, Keiko, Fredrick, Curtiss, Elizabeth, and Saeko at the center of the discussion, we begin to see the diversity in communities, in the ranks of the military, and in the backgrounds of adoptees from Asia. We begin to examine race outside the Black-White binary. We can expand the discussion of mixed race studies and mixed race Asian Americans beyond those who are Asian and White.42

The sources and oral histories from the period show that at times Blacks were blamed or absent. Black women were indirectly pitted against Japanese women for not being model wives, while Black men were erased from the military narrative in cultural spaces. Black women jointly built and supported the African American military communities by providing domestic support for their nuclear families as well as for the Japanese women who had married into the Black community. War brides from Asia learned how to be American wives from the lead of Black women. These Japanese women were absorbed into the Black community, and were taught how to be American via Black America.

Cartoons have a soft cultural power, and the Babysan cartoon strip was no doubt influential because of its appeal and numerous reproductions. Through the cartoons and subsequent books, Bill Hume taught a generation of soldiers about Japan. But Hume completely left out Black soldiers from the cartoon strip. The omission of Black men in the cartoons reinforced White normativity for the readership. Although Hume’s explanations of Japanese customs were culturally sensitive and sociologically crafted, at the same time he sexualized Japanese women by depicting them with curvy hips, large breasts, and cleavage. Calling out these biases and erasures is important to decenter Whiteness and draw attention to the sexualization of colonized bodies.43

The presence or absence of biological parents, the primary languages used, and the spaces where mixed race individuals grew up are factors that facilitated a transnational identity. Especially for individuals who are dual minorities, asserting their identity to others to address perceived dissonance often resulted in ethnic fatigue, as illustrated by the experiences of Keiko, Fredrick, and Saeko. Their transnational experiences required mixed race individuals to re-create a place and an identity even when they were not operating within the original environment. Military bases, new cities, and—for some—new families served as spaces where their identities waxed and waned. They navigated a transnational identity that changed depending upon where they lived, what languages they spoke, and how their status shifted with the changes in racial formation during the postwar period.

Acknowledgments

This research was made possible through a Fulbright Fellowship through the Institute of International Education in Japan, and a Critical Mixed-Race Studies postdoctoral fellowship through the USC Shinso Ito Center for Japanese Religions and Culture. I would like to thank Jeff Dinkler for feedback on an earlier version of this chapter and acknowledge the suggestions I received from the editors of this volume, Joanne Rondilla, Rudy Guevarra, and Paul Spickard.

Notes

1. “Do Japanese Women Make Better Wives?,” Jet Magazine, November 12, 1953, 18–21. There is an aspect of pitting Japanese women against Black women to make the comparison of a better partner, much in the same way William Petersen’s article, “Success Story, Japanese-American Style,” New York Times Magazine (January 9, 1966): 180, used Japanese Americans as an example of the model minority and pitted Blacks against Latinos.

2. The American occupation of Japan lasted from 1945 to 1952, while the American occupation of Okinawa was from 1945 to 1972.

3. Don Moser, “Japan’s G.I. Babies: A Hard Coming-of-Age,” Life (September 5, 1969): 40–47; Marc Crawford, “The Tragedy of Brown Babies Left in Japan,” Jet Magazine (January 14, 1960): 14–17; Era Bell Thompson, “Japan’s Rejected: Teen-agers Fathered by Negro Soldiers Face a Bleak Future in a Hostile Land,” Ebony (September 1967): 42–54; Hiroshi Kozawa, “Suterareta konketsu no ko” [Abandoned mixed blood children], Asahi Gurafu [Asahi Picture News] (August 4, 1957): 8–9.

4. European colonialism resulted in people of mixed background, including English Chinese, Dutch Indonesians, and French Vietnamese. See Sui Sin Far (Edith Eaton), Mrs. Spring Fragrance and Other Writings, ed. Amy Ling and Annette White-Parks (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1995); Onoto Watanna (Winnifred Eaton), A Half Caste and Other Writings (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2002).

5. See Nathan Strong, “Patterns of Social Interaction and Psychological Accommodation among Japan’s Konketsuji Population” (PhD diss., University of California, Berkeley, 1978). Strong’s work pioneered the studies of multiracial people of Japanese descent. It examines Japanese and American (both White and Black) people in Japan and their social relationships. Christine Catherine Iijima Hall, “The Ethnic Identity of Racially Mixed People: A Study of Black-Japanese” (PhD diss., University of California, Los Angeles, 1980). Hall studied thirty multiracial Black Japanese in the Los Angeles area and the psychological aspects of their self-esteem, refuting previous literature that contended they had mental and psychological problems. George Kitahara-Kich, “Eurasians: Ethnic/Racial Identity Development of Biracial Japanese/White Adults” (PhD diss., Wright Institute, 1982), developed an identity development model. Michael C. Thornton, “A Social History of a Multiethnic Identity: The Case of Black-Japanese Americans” (PhD diss., University of Michigan, 1983); Thornton studied thirteen Black Japanese interracial couples in Kansas, Washington, DC, Michigan, and Massachusetts, and how the interracial family shaped the identity of their multiracial children. Stephen Murphy-Shigematsu, “The Voices of Amerasians: Ethnicity, Identity and Empowerment in Interracial Japanese Americans” (EdD diss., Harvard University, 1986); Murphy-Shigematsu studied Amerasian identity of multiracial Japanese Americans living in the US Midwest and Northeast. Teresa K. Williams-León, “International Amerasians: Third Culture Afroasian and Eurasian Americans in Japan” (MA thesis, University of California, Los Angeles, 1989); Williams studied bilingual multiracial Japanese Americans (both White and Black) who grew up with their nuclear families on and near the military bases in Japan. Paul Spickard, Mixed Blood: Intermarriage and Ethnic Identity in Twentieth-Century America (Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1989); Paul R. Spickard, “What Must I Be? Asian Americans and the Question of Multiethnic Identity,” Amerasia Journal 23.1 (1997): 43–60. Examples in film include the 1959 movie Konketsuji, whose two child actors are Black and Japanese. In the arts, Velina Houston’s critically acclaimed play Tea has characters who are dual minorities (1994). Media articles and stories of dual minorities during the postwar period do exist, but those disproportionately include examples of the tragic mulatto in the Asian and Asian American contexts.

6. G. Reginald Daniel, More Than Black? Multiracial Identity and the New Racial Order (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 2002). Other examples of Black, White, and Native American multiracial communities include the Lumbees in North Carolina, the Melungeons in Tennessee and Kentucky, and the Ramapo mountain people around the border of New York and New Jersey. These communities are known as “triracial isolates.”

7. Ingrid Dineen-Wimberly, “Mixed-Race Leadership in African America: The Regalia of Race and National Identity in the U.S., 1862–1916” (PhD diss., University of California, Santa Barbara, 2009); Allyson Hobbs, A Chosen Exile: A History of Racial Passing in American Life (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2014); Bliss Broyard, One Drop: My Father’s Hidden Life—A Story of Race and Secrets (New York: Little, Brown, 2007).

8. Duncan Williams, “Key Moments in Japanese America’s Mixed Race History, 1868–1945,” in Hapa Japan: Constructing Global Mixed Race and Mixed Roots Japanese Identities and Representations, vol. 1, ed. Duncan Williams (Kaya Press, forthcoming 2017). In addition, these mixed families were presented in the exhibition “Visible and Invisible: A Hapa Japanese History” at the Japanese American National Museum in Los Angeles in 2011.

9. Ibid. See Figure 11.2. The first year of the Meiji period (1868–1912) was 1868, hence the name gannen, which refers to the first year (of the Meiji period) and mono meaning people.

10. Ibid.

11. Ibid.

12. Edna Bonacich and Lucy Cheng, “A Theoretical Orientation to International Labor Migration,” in Labor Immigration under Capitalism: Asian Workers in the United States before World War II, ed. Bonacich and Cheng (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1984).

13. Rudy P. Guevarra Jr., Becoming Mexipino: Multiethnic Identities and Communities in San Diego (New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 2012); Karen I. Leonard, Making Ethnic Choices: California’s Punjabi Mexican Americans (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1992). For additional scholarship that focuses on the Asian-Latino experience, see the Journal of Asian American Studies, special issue on Asian Pacific American experiences and Asian-Latino relations, 14.3 (October 2011).

14. Williams-León, “International Amerasians.”

15. Petersen, “Success Story.”

16. “Do Japanese Women Make Better Wives?,” 20.

17. Curtiss Takada Rooks, telephone interview with Lily Anne Y. Welty Tamai, May 14, 2015.

18. Black women continued to provide a support system, even for mixed race American Japanese women from Japan well into the 1960s and 1970s. See Era Bell Thompson, “Happy Ending: Grown-Up Brown Baby Finds Husband in Japan, a Home in the USA,” Ebony (July 1968): 63–68.

19. Bill Hume, When We Get Back Home from Japan (1953; repr., Tokyo: Koyoya, 1960); Bill Hume, Babysan: A Private Look at the Japanese Occupation (Rutland, VT: Charles E. Tuttle, 1958); Bill Hume, Babysan’s World: The Hume’n Slant on Japan (Rutland, VT: Charles E. Tuttle, 1959). In addition to the Stars and Stripes, Bill Hume also drew cartoons for the Navy Times and the Oppaman.

20. Hume, When We Get Back Home; Hume, Babysan; Hume, Babysan’s World.

21. Isaiah Helekunihi Walker, Waves of Resistance: Surfing and History in Twentieth-Century Hawai‘i (Honolulu: University of Hawai‘i Press, 2011), 90–92.

22. Robert Harvey, Insider Histories of Cartooning: Rediscovering Forgotten Famous Comics and Their Creators (Missoula: University Press of Mississippi, 2014).

23. John W. Dower, Embracing Defeat: Japan in the Wake of World War II (New York: Norton, 1999), 130.

24. Michael Cullen Green, Black Yanks in the Pacific: Race in the Making of American Military Empire after World War II (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2010); Curtis James Morrow, What’s a Commie Ever Done to Black People? A Korean War Memoir of Fighting in the U.S. Army’s Last All Negro Unit (Jefferson, NC: McFarland, 1997).

25. Paul Gilroy, The Black Atlantic: Modernity and Double-Consciousness (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1993) looks at Europe, Africa, and the Americas; Etsuko Taketani, The Black Pacific Narrative: Geographic Imaginings of Race and Empire between the World Wars (Hanover, NH: Dartmouth College Press, 2014); Vijay Prashad, Everybody Was Kung Fu Fighting: Afro-Asian Connections and the Myth of Cultural Purity (Boston: Beacon Press, 2001); Heike Raphael-Hernandez and Shannon Steen, eds., AfroAsian Encounters: Culture, History, Politics (New York: New York University Press, 2006).

26. Ingrid Dineen-Wimberly, “To ‘Carry the Black Man’s Burden’: T. Thomas Fortune’s Vision of African American Colonization of the Philippines, 1902–1903,” International Journal of Business and Social Science 5.10 (2014): 69–74.

27. Mitzi Uehara Carter, “Mixed Race Okinawans and Their Obscure In-Betweenness,” Journal of Intercultural Studies 35.6 (2014): 646–661; Ariko Ikehara, “Black-Okinawa and the MiXtory: Production of Mixed Spaces in Okinawa” (paper, University of Southern California Sawyer Seminar, April 26, 2014). For a historical overview of Black military personnel in Japan and Korea, see Green, Black Yanks in the Pacific.

28. Bonacich and Cheng, “Theoretical Orientation.”

29. For Germany, see Heide Fehrenbach, Race after Hitler: Black Occupation Children in Postwar Germany and America (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2005).

30. Fernando Herrera Lima, “Transnational Families: Institutions of Transnational Social Space,” in New Transnational Social Spaces: International Migration and Transnational Companies in the Early Twenty-First Century, ed. Ludger Pries (New York: Routledge, 2001), 91.

31. US Congress House of Representatives, H.R. 711, introduced by Walter Judd, January 3, 1951.

32. Chan is an honorific title used for children or among very close friends. This is compared to san, which is the honorific title used with adults.

33. Miki Sawada, Haha to ko no kizuna erizabesu sandazu homu no san ju nen [A bond between a mother and a child: Thirty years of the Elizabeth Saunders home] (Kyoto: PHP Kenkyujo, 1980), 53–57.

34. Email correspondence with Lily Anne Y. Welty Tamai, June 22, 2009.

35. Mattie H. Briscoe, “A Study of Eight Foreign-Born Children of Mixed Parentage Who Have Been Adopted by Negro Couples in the U.S.” (MA thesis, Atlanta University School of Education, 1956).

36. Coincidentally, Ariana Miyamoto, who was crowned the 2015 Miss Japan and will be representing Japan in the Miss Universe pageant, was born in Keiko’s hometown of Sasebo, Nagasaki, in 1994 and is also Japanese and Black. After reading about Ariana, Keiko remarked, “Jidai ga kawatte yokatta [I’m so glad the times have changed]. It’s good for Japan. It’s good for us.” Keiko Clark, phone interview with Lily Anne Y. Welty Tamai, March 14, 2015.

37. Fredrick Cloyd, “Assimilating the Black Japanese—Japan and the US: Reflections” (September 3, 2013), https://waterchildren.wordpress.com/page/3/. See Fredrick Cloyd, Dream of the Water Children (New York: 2Leaf Press, forthcoming).

38. Curtiss Takada Rooks, “Reflections of a Suntanned Samurai: 25 Years of Hap(a)in’ Around” (USC Mellon Sawyer Seminar, April 26, 2014).

39. Curtiss Takada Rooks, “On Being Japanese American,” Discover Nikkei (October 26, 2007), http://www.discovernikkei.org/en/journal/2007/10/26/on-being-japanese-american.

40. Elizabeth Kamizato, interview with Lily Anne Y. Welty Tamai, December 23, 2007.

41. Kina Saeko, interview with Lily Anne Y. Welty Tamai, Chatan, Okinawa October 19, 2009.

42. Greg Robinson, “The Early History of Mixed-Race Japanese Americans,” in Williams, Hapa Japan.

43. For further information on women, war, and colonialism, see Cynthia Enloe, Bananas Beaches and Bases: Making Feminist Sense of International Politics (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2000); Akemi Johnson, “The Body Politic: When US Soldiers Venture Abroad, Women’s Bodies Can Become the Occupied Territories,” Nation (April 28, 2014), http://www.thenation.com/article/179249/body-politic-when-us-soldiers-venture-abroad-womens-bodies-can-become-occupied-territ.