PARLIAMENT SQUARE was laid out in 1868 as an approach to Charles Barry’s Houses of Parliament. Since it was created it has been filled with statues of politicians and statesmen, including seven prime ministers. Unfortunately, access to the central area is not easy, as there are no pedestrian crossings.

The massive bulk of Churchill’s statue looms over Parliament Square.

The most prominent statue is that of Sir Winston Churchill (1874–1965), Britain’s charismatic leader during the Second World War and Nobel Prize winning author. He faces the House of Commons, where he spent so many years of his political career. There was much debate about where a statue to Churchill should be sited, but Grey Wornum, who redesigned the square in the 1960s, set aside a plot in its north-east corner for the purpose, and it seems Churchill had his eye on the same spot for himself. An appeal fund was set up in 1970 and the money was raised very quickly. A competition was held for the design of the statue, and the winner was Ivor Roberts-Jones. The statue was due to be unveiled in 1973 by the Queen, but on the day she invited Churchill’s widow, Clementine, to do the honours. The statue shows Churchill bareheaded in a military greatcoat, striding forwards with determination, walking stick in hand. During the May Day demonstration in 2000, the monument was badly vandalised, with graffiti daubed all over the plinth and Churchill himself suffering the indignity of being given a green Mohican haircut.

Glyn Williams’s dynamic statue of David Lloyd George.

Behind is a memorial to David Lloyd George (1863–1945), the Welsh Liberal politician who was prime minister from 1916 to 1922. Although a great wartime leader and a social reformer, there were many complaints about the proposal to erect the statue, because Lloyd George had tarnished his reputation by selling honours to boost his party’s coffers. The statue, by Glynn Williams, shows Lloyd George as a dynamic figure, with his coat billowing out behind him, and is very different from the more formal statues in the square. The plinth is a piece of Welsh slate from Penrhyn. The statue was unveiled in 2007 by the Prince of Wales.

The statue to Field Marshal Jan Christian Smuts (1870–1950), South African statesman and soldier, was due to be unveiled in 1956 by Sir Winston Churchill, but he was indisposed and W. S. Morrison, the Speaker of the House of Commons, stepped in at the last moment. Smuts was prime minister of South Africa during the Second World War, and was often called on to advise the War Cabinet in London. More controversially, he was also responsible for the introduction of Apartheid. The statue is by Jacob Epstein, and shows Smuts striding energetically forwards, his hands behind his back. The granite pedestal was specially ordered from South Africa, and its late arrival delayed the erection of the statue. Epstein was a controversial choice for the commission, but the statue proved to be much less contentious than some of his earlier work.

Epstein’s statue of Jan Smuts.

In the north-west corner is a statue to Henry John Temple, 3rd Viscount Palmerston (1784–1865). Palmerston was a hard-working and supremely selfconfident Foreign Secretary, successfully using gunboat diplomacy to get his way at times. He became prime minister during the Crimean War, at the age of seventy, and held the office twice. He was a great womaniser, with many mistresses, one of whom he married when she was widowed. His last words were said to be, ‘Die, my dear doctor? That’s the last thing I shall do!’ His statue, by Thomas Woolner, was erected in 1876, and is one of the bestdressed statues in the square. Unusually, the plinth gives his name, but no dates.

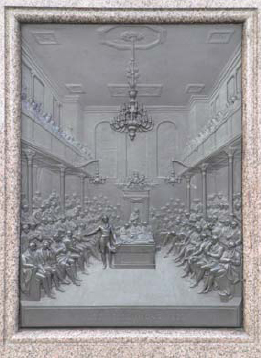

Plaque on the plinth of the Earl of Derby’s statue, showing him speaking in the Commons chamber in St Stephen’s Chapel, which burnt down in the fire of 1834.

The first memorial on the western side is to Edward George Geoffrey Smith Stanley, 14th Earl of Derby (1799–1869), perhaps the least charismatic nineteenth-century prime minister. He was, however, an excellent debater, helped to abolish slavery, and was the first person to be prime minister three times. He still holds the record as the longest-serving leader of the Conservative party. His statue is by Matthew Noble, and was unveiled in 1874 by Disraeli. Around the granite plinth are four bas reliefs by Horace Montford depicting important moments in Derby’s career.

Next is the statue of Benjamin Disraeli, Earl of Beaconsfield (1804–81), who was an important politician as well as a popular novelist. He was Chancellor of the Exchequer three times and prime minister twice. Born into a Jewish family, he was baptised at an early age, and yet remained proud of his Jewishness. He was a colourful figure, a flamboyant dresser in his youth, always the egotist, but a great charmer and he was a favourite of Queen Victoria, who much preferred him to his dour opponent, Gladstone. The statue is by Mario Raggi, and is an excellent likeness, as the sculptor had made a bust from the life shortly before Disraeli died. It was unveiled on 19 April 1883, the second anniversary of his death, a date known as ‘Primrose Day’, after Disraeli’s favourite flower. For many years primroses would be left by the statue each year on that date. He is shown in peer’s robes and wearing the Garter regalia.

Benjamin Disraeli in his peer’s robes.

The statue of Sir Robert Peel (1788–1850) is by Matthew Noble. Peel was prime minister twice, but is better known as the creator, as Home Secretary, of the first united police force in 1829. Despite initial doubts, the public came to accept the new system, and the policemen were soon affectionately referred to as ‘Bobbies’ or ‘Peelers’ after their founder. Soon after his death, statues of Peel were erected in many other cities, and also in the City of London, but the national memorial took considerably longer to arrange. The first statue was made by Marochetti in 1853, but it was considered too large, so he made a smaller version, but this was also rejected and it was removed in 1868 and melted down. Noble was then commissioned to make a new statue, and this was unveiled in 1877.

Nelson Mandela’s statue is much less formal than the others in Parliament Square, including that of Robert Peel behind him.

Amid all the stiff-backed statesmen of the square, Ian Walters’ statue of Nelson Mandela (1918–), former president of South Africa, is considered by some to be an intruder, and by others as a breath of fresh air. He is shown addressing a crowd, dressed in one of his trademark floral shirts. It stands on a much lower plinth than the other statues, reflecting his status as a man of the people. The statue was originally intended for the more appropriate setting of Trafalgar Square, close to South Africa House and the spot where, for many years, anti-Apartheid protesters campaigned for his release from prison on Robben Island. Westminster Council, however, felt that it would cause an obstruction, but gave permission for it to be erected here. Mandela was present when the statue was unveiled in 2007, and he spoke of a visit to London forty-five years earlier when he and fellow activist, Oliver Tambo, had jokingly wondered if a statue of a black person would ever stand next to that of Smuts. Ian Walters also created a bust of Mandela in the 1980s, which stands outside the Royal Festival Hall (see page 188), and there is a bust of Tambo in Muswell Hill (see page 206).

On a patch of grass on the corner of Great George Street is the oldest statue in the square, to the politician George Canning (1770–1827). At a time when, to make your way in politics, you had to have a title and plenty of money, Canning was unusual in succeeding by hard work and talent. He was twice Foreign Secretary, when he recognised the newly liberated Latin American countries, and for the last few months of his life was prime minister. The statue, by Sir Richard Westmacott, is neo-classical in style, with Canning wearing distinctly non-contemporary clothes. It was originally put up in 1832 in a garden near St Margaret’s Church looking out over New Palace Yard. Because of the construction of new roads and the Underground railway, the statue was moved to its present position in 1867. The statue was considered by some to be one of Westmacott’s best, though it was also criticised by others. According to the Observer, ‘Nothing so vile in taste, or so defective in execution, has outraged public opinion for some years’.

Westmacott’s statue of Canning portrays him in antique apparel.

The dignified statue of Abraham Lincoln is a copy of the one in Chicago.

Further south, in front of the Supreme Court, is the impressive statue of Abraham Lincoln (1809–65), the sixteenth president of the United States. It is a copy of a statue in Chicago by Augustus Saint-Gaudens, and was presented by the American people, but London very nearly received a very different statue. The original offer of a statue, to celebrate the anniversary of the Treaty of Ghent in 1814 and one hundred years of peace between the United States and Great Britain, was made in 1914. It was assumed that the statue was the one by Saint-Gaudens, but in 1917 the American Committee ordered a casting of a statue by George Gray Barnard, which had recently been erected in Cincinnati. There were protests on both sides of the Atlantic, as it was considered to be a poor likeness and an unworthy gift, and was known in American art circles as ‘The Tramp with the Colic’. The final decision was delayed until after the war, and in the end it was the replica of the Saint-Gaudens that was sent to London, a statue which Sir George Frampton claimed was ‘perhaps the most beautiful monument in America’. The Barnard statue was presented instead to Manchester, where it can still be seen. The London unveiling took place in 1920, carried out by the Duke of Connaught, the president of the Anglo-American Society. The statue is a dignified and powerful representation of Lincoln, showing him standing, head bowed in thought, in front of a chair.

On the east side of the square, in front of Westminster Hall, is a monument to Oliver Cromwell (1599–1658), Parliamentary leader during the Civil War and Lord Protector from 1653 to 1658 (see overleaf). Cromwell has always been a controversial figure, as he had a hereditary monarch, Charles I, beheaded and became something of a despot himself. He was also much hated by the Irish because of the brutality of his troops in the last days of the Civil War. During the construction of the new Houses of Parliament he was denied a statue among the monarchs adorning the exterior of the building. John Bell put forward a proposal for a statue to be erected outside the Houses of Parliament, but he died in 1895, and Sir (William) Hamo Thornycroft was commissioned to produce one. However, the scheme was abandoned when its funding was opposed by Irish MPs. An anonymous donor, most probably Lord Rosebery, offered to pay for the statue, and it was erected in 1899 to celebrate the tercentenary of Cromwell’s birth. The statue stands on a lawn well below the pavement, but it stands on a tall plinth so that it is clearly visible at street level. The Protector is shown bare-headed and carrying a sword and Bible, to symbolise the two aspects of his character, and on the front of the plinth is a crouching lion. His gaze is lowered, as if to avoid eye contact with the bust of Charles I which occupies a niche above the doorway of St Margaret’s Church opposite. It is one of the busts found by Hedley Hope-Nicholson (see page 20) and was given to the church in 1956. When Cromwell died, he was buried in Westminster Abbey, but after the Restoration in 1660, Charles II had his body exhumed and hanged at Tyburn. His head was stuck on a spike on the roof of Westminster Hall, where it stayed for some twenty years until it was blown down in a gale. It was retrieved by a sentry and it then passed through many hands, but is now buried at Sidney Sussex College, Cambridge. Every year on 3 September, the anniversary of Cromwell’s death, the Cromwell Association holds a service at the statue.

Cromwell’s statue stands in front of Westminster Hall.

In Old Palace Yard, by the entrance to the House of Lords, is Baron Marochetti’s highly romantic equestrian statue of Richard I, Coeur de Lion (1157–99). Although king for ten years, Richard spent very little time in England, and is best known for the part he played in the Crusades. He died after being shot by an archer when attacking the castle of Chalus in France, and was buried at Fontrevault Abbey. A plaster cast of Marochetti’s statue was displayed at the Great Exhibition of 1851 and was greatly admired. The ambitious Italian sculptor was not popular with the artistic establishment, but had the patronage of Queen Victoria, and Prince Albert himself chose the setting for the bronze version of the statue. It was erected here in 1860, even though Charles Barry, the architect of the new Houses of Parliament, objected to it being placed in front of his new building. It shows Richard as a crusader knight, sword held high as if about to lead a charge. The two bas reliefs which, according to Marochetti, were in the style of Ghiberti’s Baptistry doors in Florence, were added to the plinth in 1866. The one visible to the public shows Richard on his deathbed, forgiving the archer who shot him, though he was treacherously flayed alive after the king’s death. A charming detail is the cat sleeping under a chair. The other relief shows Crusaders fighting the Saracens. During the Second World War a bomb landed very near the statue, but the only damage caused was to the sword, which was bent by the blast.

Marochetti’s romantic image of Richard the Lionheart.

George V’s statue at the east end of Westminster Abbey.

The statue of Emmeline Pankhurst shows her addressing a meeting.

On the opposite side of the road, on a small patch of grass at the east end of Westminster Abbey, is the statue of George V (1865–1936). The statue, of Portland stone, was created by Sir William Reid Dick, and Sir Giles Gilbert Scott acted as architect. The original model, which included a Gothic canopy, was much criticised, and the design was simplified. The statue was carved in one of the Portland quarries, but the outbreak of war delayed its erection, and it spent the war years in a tunnel at the quarry. It was finally unveiled in 1947 by George VI, who was accompanied by members of the royal family, including Queen Mary. The king is shown in the uniform of a Field Marshal and Garter robes, and holds the Sword of State. The figure is set well forward on the high plinth, and the long, flowing cloak is a strong architectural element of the design.

Just inside the entrance to Victoria Tower Gardens is a memorial to Emmeline Pankhurst (1858–1928) and her favourite daughter Christabel Harriette Pankhurst (1880–1958), two of the leading figures in the women’s suffrage movement. Emmeline formed and led the Women’s Social and Political Union, and Christabel worked as an organiser and the organisation’s lawyer. They began by campaigning peacefully, but, frustrated by a lack of progress, became more militant, and Emmeline and many of her followers were arrested many times. In 1918 women over the age of thirty were given the vote, but full equality only came a couple of weeks after Emmeline’s death. The statue of Emmeline, by Arthur George Walker, was unveiled in 1930 by the prime minister, Stanley Baldwin. In 1959 the low curved wall was added, with plinths at each end, one carrying a bronze replica of the WSPU prison badge, the other a relief portrait of Christabel by P. Hills.

Rodin’s Burghers of Calais in Victoria Tower Gardens.

Inside the gardens is Auguste Rodin’s famous sculpture The Burghers of Calais. It shows a scene from 1347 when, after a long siege, the six burghers, with halters round their necks, surrendered themselves to Edward III to save their town. The first sculpture was erected in Calais in 1895, and this version is a replica worked on by the artist. It was bought for the nation by the National Art Collections Fund (now the Art Fund) and erected here in 1915. Its original location, on a 16-foot-high plinth in a corner of the gardens, was much criticised at the time, as it made the sculpture inaccessible, but as the setting had been agreed with the sculptor, it remained there for many years. During the Second World War the sculpture was put in storage to save it from bomb plinth, allowing it to be more easily damage, and in 1956 it was moved to a appreciated in the round. However, the more open space and on a much lower new plinth allowed people to climb onto it and the sculpture was damaged. In 1999 it was taken away for restoration and in 2003 it was unveiled on a new plinth.

The Buxton Memorial Fountain commemorates the work of those who worked to abolish the slave trade.

Towards the southern end of the gardens is a curious, multi-coloured structure, which often appears in the background on television news broadcasts. This is the Buxton Memorial Fountain, erected to commemorate the abolition of slavery in 1834, and in particular the work of Sir Thomas Fowell Buxton (1786–1845), a politician who worked tirelessly in the campaign against slavery. It was commissioned by his son, Charles Buxton, and was designed by Samuel Sanders Teulon. In 1865 it was installed in Parliament Square, in the corner where Palmerston now stands. In the 1950s, when plans were made for the rearrangement of Parliament Square, it was proposed to move it to a new location and the suggestion provoked much debate. Some felt it should stay where it was, while others considered the fountain to be an eyesore and did not want it to be rebuilt anywhere. In 1957 it was moved to its present location. The structure was built using many different stones, including granite, sandstone, limestone and marble, and the detailing is Gothic in style, with medieval-style carving and colourful mosaics. After restoration by the Royal Parks, it was unveiled in 2007 to commemorate the 200th anniversary of the 1807 Act which abolished the slave trade. Originally eight bronze figures of English monarchs stood on the pinnacles, but they were stolen in the 1960s and ’70s. In 1980 they were replaced with fibreglass copies, but these were not installed in 2007.