ONE OF THE BEST PLACES in London to study statues is along the Victoria Embankment. When it opened in 1870, it not only offered a new route from the City to Westminster, but new gardens were created on land reclaimed from the Thames. These gardens are now filled with a great variety of statues, and there are a number of memorials on the river wall as well.

One of the capital’s best known statues is Boadicea by Thomas Thornycroft, which stands at the north end of Westminster Bridge, opposite the Houses of Parliament. Boadicea (or Boudicca) was the queen of the Iceni who raised a rebellion against the Romans, destroying the cities of Colchester (Camulodunum), St Albans (Verulamium) and London (Londinium). After being defeated in battle in AD 62 she committed suicide. Her burial place is not known, but there is a tradition that she is either under platform 10 of King’s Cross Station or buried at Parliament Hill; it was the London County Council’s decision to investigate the latter site in 1894 that prompted John Thornycroft to offer them his father’s sculpture. Thomas Thornycroft, who died in 1885, had spent fifteen years on the work and the plaster cast had been stored at his home in Chiswick. The LCC were very impressed by the work and were keen to accept the offer, but there were problems raising the necessary funding, due to the high cost of casting such a large sculpture. Even when the problem was resolved in 1898 there was still the problem of finding a good site for it. Originally it was planned to erect it on Parliament Hill, but a plaster model was placed on the Embankment as an experiment. There was considerable criticism of the statue’s old-fashioned design, and the inappropriateness of the site for such a monumental sculpture, but the LCC went ahead and the statue was unveiled in 1902. It is a very dramatic composition, with the queen, accompanied by her two daughters, driving her horse-drawn chariot at the Roman army. However, the costume and chariot are fantastic inventions of the sculptor, rather than historically accurate, especially the anachronistic scythes on the wheels.

The building next to the modern Portcullis House is the Norman Shaw Building, now parliamentary offices, but built as New Scotland Yard by Richard Norman Shaw (1831–1912), his only major public building. Under an upper balcony is a memorial plaque to Shaw by W. R. Lethaby, with a portrait relief by Sir (William) Hamo Thornycroft, installed in 1914.

The dramatic, but historically inaccurate, statue of Boadicea by Westminster Bridge.

The next section of the Embankment is dedicated to military memorials of various kinds. On a wide section of the Thamesside footpath is the substantial Battle of Britain Memorial, which was unveiled in September 2005 by Prince Charles. It commemorates the fighter pilots known as ‘the few’, as well as the ground crew, who between them won the aerial Battle of Britain against the Luftwaffe in 1940. The £1.65m memorial was commissioned by the Battle of Britain Historical Society and paid for by public subscription. It consists of two bronze friezes by Paul Day, on the back of which are inscribed the names of the 2,936 pilots and ground crew who took part, seventy of whom attended the unveiling. One of the friezes shows the various activities of Fighter Command, including observers and mechanics, with the ‘scramble’ at its centre, the pilots dramatically rushing out of the monument. The other panel concentrates on people on the ground, some watching the dogfights, women in the munitions factories, and St Paul’s amid the ruins. Underneath is Winston Churchill’s famous phrase which gave the pilots their nickname: ‘Never in the field of human conflict was so much owed by so many to so few’.

This portrait of Richard Norman Shaw marks his only major public building.

The ‘scramble’ is dramatically portrayed on the Battle of Britain Memorial.

Further along the Embankment, overlooking the Thames at Whitehall Stairs, is the Royal Air Force Memorial, which commemorates those serving in the RAF and other air forces who died in both world wars. It consists of a simple Portland stone pylon, designed by Sir Reginald Blomfield, surmounted by a gilded bronze eagle, the work of Sir William Reid Dick. The eagle was originally meant to face the road, but Blomfield changed his design so that it faces, symbolically, towards France. On the Embankment side is the winged badge of the RAF and its motto, Per ardua ad astra, and below is the dedication to those who served in the First World War. The memorial was unveiled in 1923 by the Prince of Wales (the future Edward VIII). A further inscription was unveiled by Lord Trenchard in 1946 to remember those who lost their lives in the Second World War. The RAF Benevolent Fund had originally wanted the memorial to stand between Westminster Abbey and St Margaret’s Church, so this location was their second choice, but it has since been joined by a number of related memorials, creating a place of special significance.

The Royal Air Force Memorial, topped by a golden eagle.

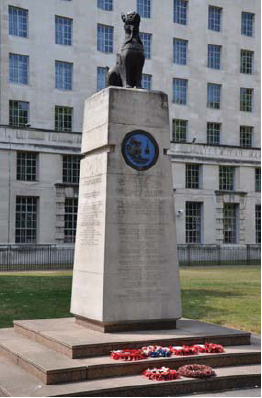

The Chindit Memorial, with the portrait medallion of Orde Wingate.

At the Westminster end of the gardens in front of the Ministry of Defence is the Chindit Memorial, erected in memory of the Chindits, a force made up of British and Gurkha soldiers, who fought against the Japanese in the Burmese jungle in 1943–4. Their name comes from the Chinthe, a mythical beast that guards Burmese temples, and a bronze statue of one stands on top of the memorial. The Chindits were led by Major General Orde Wingate, an unorthodox but dynamic leader, who died in action in March 1944, and there is a portrait medallion of him on the reverse of the monument. The memorial was unveiled in October 1990 by the Duke of Edinburgh. It was designed by the architect David Price and the sculpture is by Frank Foster.

Nearby is the statue of Hugh Montague Trenchard, Viscount Trenchard (1873–1956), known as ‘the father of the Royal Air Force’, appropriately standing in front of the former Air Ministry. He was clumsy, inarticulate and had a famously loud voice, earning him the nickname ‘Boom’, but he also had limitless energy, was a stern disciplinarian and a great organiser. His first career was in the army, but later he learned to fly and became the first Chief of the Air Staff of the newly formed Royal Air Force in 1918, building it into a powerful force. The statue, by William McMillan, shows Trenchard in RAF uniform, and was unveiled in 1961 by the prime minister, Harold Macmillan.

McMillan’s statue of Trenchard, ‘father of the RAF’

The Fleet Air Arm Memorial with a winged airman.

Not far away is a rather different kind of monument, the Fleet Air Arm Memorial, which was unveiled in 2000 by the Prince of Wales. It is dedicated to the thousands of men and women who lost their lives while serving in the Fleet Air Arm of the Royal Navy, and lists the wars and battles in which they fought, from the First World War to the first Iraq war of 1991. On top of a column of Portland stone is the bronze figure of Daedalus, the Greek inventor who made wings for himself and his son, Icarus, who flew too close to the sun and died. The figure is clearly of an airman in uniform, and he has an air of sadness about him, with his head bowed as he remembers the many colleagues who have died in action. The sculpture is by James Butler, who worked with architects Trehearne & Norman.

Further along the gardens is Oscar Nemon’s larger-than-life statue of Charles Frederick Algernon Portal, Viscount Portal of Hungerford (1893–1971), who was Chief of the Air Staff during most of the Second World War. Portal served in the Royal Flying Corps in the First World War, and earned three decorations by the time he was twenty-five. Between the wars his potential was recognised by Trenchard and he was rapidly promoted. In April 1940 he ran Bomber Command and in October was made Chief of the Air Staff, remaining in charge throughout the rest of the war. According to Eisenhower, he was the greatest British war leader, ‘greater even than Churchill’, and Churchill himself claimed that ‘Portal has everything’. The statue was unveiled in 1975 by Harold Macmillan, on what would have been Portal’s eighty-second birthday.

Oscar Nemon’s statue of Portal is in his distinctive rugged style.

Thornycroft’s statue of Gordon used to stand in Trafalgar Square.

The last statue in this section of the gardens is of General Charles George Gordon (1833–85). Gordon was a career soldier, serving in the Crimea, India and China, and was often referred to as ‘Chinese Gordon’. As well as being a fanatical Christian, he was opinionated, self-righteous and insubordinate, and he himself said, ‘I know if I was chief I would never employ myself, for I am incorrigible.’ His most famous exploits were in the Sudan: he was sent there to rescue the Egyptian forces from an insurrection by the Mahdi in Khartoum, where he in turn was besieged. He defended Khartoum for a year, and the British Government dithered over sending relief troops, who finally arrived on 28 January 1885, two days after he had been killed. Gordon became a martyr and a national hero, and in October 1888 this statue, by Sir (William) Hamo Thornycroft, was unveiled, with no ceremony or speeches, in the centre of Trafalgar Square. In 1943 the statue was removed to make way for a Lancaster bomber, as part of a ‘Wings for Victory’ display. The statue returned after the war, but in 1947 it was proposed to move the statue permanently to make way for the new fountains being built as part of the Beatty and Jellicoe memorials. Plans to send it to Sandhurst led to a public outcry, and the Government finally agreed to place it in the new gardens being created on the Victoria Embankment by the new Air Ministry offices, where it was installed in 1953. It is a fine statue, the sculptor following Gordon’s brother’s request that it be ‘as little military as possible’. Instead it shows Gordon in pensive mood, carrying a Bible in his left hand and with his famous ‘whangee’ cane under his right arm. On the sides of the plinth are bronze plaques of Fortitude, Faith, Charity and Justice. Although Gordon is a military hero of the old school, he is still remembered, and wreaths are laid at the foot of the statue to this day.

William Tyndale was persecuted for translating the Bible into English.

The gardens north of Horse Guards Avenue contain a more varied selection of memorials. The first is to William Tyndale (c. 1494–1536), an important figure of the English Reformation. He translated the Bible into English, but was persecuted for his work and forced to flee to Germany, where his New Testament was printed. Copies were smuggled into England, though many of them were burned. He later worked on the Old Testament in Antwerp, but in 1525 he was arrested and burned as a heretic. His last words at the stake were, ‘Lord, open the king of England’s eyes’. Ironically, within a year of his death a complete English Bible could be found in every parish church, on the King’s orders. The statue, by Sir Joseph Edgar Boehm, was unveiled in 1884 by Lord Shaftesbury. Tyndale rests his right hand on a copy of his New Testament, which stands on a printing press copied from a contemporary one in the Plantin Museum in Antwerp.

Nearby is the statue of Sir Henry Bartle Edward Frere (1815–84), by Sir Thomas Brock. Frere was a statesman and administrator who spent thirty-three years working in India, where he developed the cities of Sind and Bombay, improving harbours, transport, sanitation and trade. He later managed to abolish the Zanzibar slave trade, but his time as High Commissioner in South Africa was less successful. Brock’s statue, unveiled in 1888 by the Prince of Wales, shows Frere in the robes of a Knight Commander of the Star of India.

Frere was an administrator who spent most of his working life in India.

The colossal statue of General Outram is surrounded by military symbols.

At the far end of the gardens is the impressive memorial to General Sir James Outram (1803–63). He first went to India aged sixteen and remained there for most of his life. At the relief of Lucknow he was happy to serve under Havelock, despite his more senior rank. He also served with Napier, who called him the ‘Bayard of India’, though they were later to fall out. A Bayard was a knight without fear or reproach, and the epithet has been used to refer to him ever since. The 14-foot bronze statue by Matthew Noble was unveiled in 1871, and was the first statue to be erected in the Embankment gardens. Outram wears the Star of India and has a cannon at his feet, and there are Indian trophies around the 19-foot granite plinth.

Outside the gardens, overlooking the Embankment, is a memorial to Samuel Plimsoll (1824–98), the ‘Sailors’ Friend’. Plimsoll campaigned long and hard against the ‘coffin-ships’ – poorly maintained and overloaded ships that often disappeared without trace, and with great loss of life. He faced much opposition, but his persistence led to the Merchant Shipping Act of 1876, which forced ship owners to mark their vessels with a load line, still known as the ‘Plimsoll Line’. The memorial, by Ferdinand Blundstone, was unveiled in 1929, and was funded by members of the National Union of Seamen. Below a bust of Plimsoll are the figures of Justice and a sailor, and the railings on either side feature seahorses and the Plimsoll Line.

The memorial to Samuel Plimsoll, the ‘Sailors’ Friend’.

The memorial to Bazalgette stands on the Embankment he built.

On the Embankment wall facing Northumberland Avenue is a memorial to Sir Joseph William Bazalgette (1819–91), one of the truly great Victorian engineers. He left a massive legacy in London, including three Thames bridges, major new streets such as Shaftesbury Avenue and Northumberland Avenue, and the Victoria, Albert and Chelsea Embankments, but his most important and least visible achievement was the building of a huge network of sewers which is still in use today. Part of it runs under the Victoria Embankment itself, which was also designed to house the District Line. His memorial could therefore not be better placed. It was designed by George Symonds and was unveiled in 1901. It consists of a bronze portrait bust within a rather classical temple structure, containing many sculptural details such as dolphins representing the Thames and surveying and engineering implements on the two columns. In the pediment is the Bazalgette coat of arms, and beneath it the Latin phrase, Flumini vincula posuit (‘he put the river in chains’).

On the river wall on the northern side of Hungerford Bridge is a memorial to the playwright Sir William Schwenck Gilbert (1836–1911). Gilbert trained as a barrister, but found fame as a wit and dramatist of both comedy and tragedy. In 1869 he met the composer, Arthur Sullivan, and they soon teamed up as ‘Gilbert and Sullivan’, writing the Savoy operas for Richard D’Oyly Carte, who built the Savoy Theatre to stage them. They were a highly successful partnership, producing such operettas as The Mikado and The Gondoliers, which are still regularly performed today. In 1907 Gilbert was the first dramatist to be knighted. The bronze memorial is by Sir George Frampton and it was erected in 1915. It has a profile portrait of Gilbert, flanked by the figures of comedy and tragedy, and below is the apt epitaph, ‘His foe was folly and his weapon wit’. Sullivan’s memorial is in Victoria Embankment Gardens, only a few hundred yards away.

The memorial to the writer W. S. Gilbert is one of three by Frampton on the Embankment wall.

Cleopatra’s Needle is over three thousand years old, and has stood by the Thames since 1878.

Further along the Embankment is Cleopatra’s Needle which, despite its name, does not commemorate the great Egyptian queen. It was originally erected in Heliopolis in around 1475 BC, but was later moved to Alexandria. Its original dedication was to Tuthmosis III, though the names of Ramses II and Cleopatra were added at a later date. In 1820 Mohamed Ali, the Turkish Viceroy, presented the 69-foot granite obelisk to Britain in recognition of its efforts to free Egypt from occupation by the French forces, and a plaque on the river side states that it is ‘a worthy memorial of our distinguished countrymen Nelson and Abercromby’. Because of the technical difficulties of moving the obelisk, it lay for many years abandoned in the desert. It was finally collected in 1877, and towed by sea to London, though it was nearly lost in a storm in the Bay of Biscay. It was erected on the Embankment in 1878, using hydraulic jacks. To give it stability, four bronze corner pieces in the form of wings were added by George Vulliamy, who also made the two sphinxes that guard it. One of the sphinxes was damaged during an air raid in 1917, and the scars can still be seen.

Opposite Cleopatra’s Needle is the Anglo-Belgian Memorial, a gift from the Belgian nation in gratitude for the help given to the thousands of Belgian refugees who lived in England during the First World War. It was unveiled in 1920 by Princess Clementine of Belgium. The memorial was designed by Sir Reginald Blomfield, and the bronze sculpture, by the Belgian sculptor, Victor Rousseau, represents a Belgian woman with a boy and girl carrying garlands.

This sculpture by Victor Rousseau is part of the Anglo-Belgian Memorial.

The section of the Victoria Embankment Gardens between the Hungerford and Waterloo Bridges contains a diverse collection of memorials. The first one, near the York Watergate, is of the great Scottish poet, Robert Burns (1759–96 – see overleaf), and is a thoroughly Scottish affair. The statue itself is by Sir John Steell, the most important Scottish sculptor of the nineteenth century, and is a variant of his statues in Dundee and New York. It was donated by John Gordon Crawford, a retired Glasgow merchant, and stands on a pedestal of pink Peterhead granite, with a base of Aberdeen granite. The poet is seated, in pensive mood, on the broken stump of a tree. He holds a pen in his right hand and at his feet is a scroll with the words, ‘O sweet to stray and pensive ponder a heart-felt song’. The memorial was unveiled in 1884 by Lord Rosebery, the Commissioner of Works.

Close by is the unusual and attractive memorial to the Imperial Camel Corps (see overleaf), commemorating those who died during the First World War fighting in the deserts of Egypt, Sinai and Palestine. It was unveiled in 1921. The sculptor was Major Cecil Brown, himself a member of the Corps, and the memorial shows a yeoman on a camel. Bronze plaques on each side show scenes from the campaigns.

The delightful memorial to the Camel Corps, with the statue of Robert Burns in the background.

A short distance away, on a tall plinth, is the statue of Sir Wilfrid Lawson (1829–1906), a long-forgotten nineteenthcentury politician. He was an MP for nearly fifty years, and was an indefatigable campaigner for temperance, but also supported women’s rights and religious equality. With his long beard, he looks a strict and dour figure, but he was an excellent public speaker and a great wit, and it amused him that he was referred to as ‘the old cracked teapot’. The funds for the statue were collected by the United Kingdom Alliance, the temperance organisation of which Lawson had been President, and it was unveiled by Herbert Asquith, the prime minister, in 1909. David McGill’s statue shows Lawson holding notes in his right hand, about to make a speech. Originally there were bronze figures of Temperance, Peace, Fortitude and Charity around the base, but these were stolen in 1979.

Lawson is making a speech, hand in pocket – a very lifelike pose.

Fawcett became Postmaster-General, despite his blindness.

Opposite is a monument designed by Sir Edwin Lutyens and erected in 1930 to commemorate Herbert Francis Eaton, Baron Cheylesmore (1848–1925), who was Mayor of Westminster in 1904 and from 1912 to 1913 was Chairman of the London County Council. It is a very simple memorial, with no portrait, but with the family crest and a small pond.

A few metres away is a drinking fountain in memory of Henry Fawcett (1833–84), who was blinded in a shooting accident when still a young man, but came to terms with his blindness and had a long and successful political career. In 1880 he was made Postmaster-General, and during his tenure he introduced the parcel post. He was also a supporter of women’s rights and the memorial fountain was erected by ‘his grateful countrywomen’ in 1886. It was designed by Basil Champneys and the bronze plaque is an early work of George Frampton, incorporating a portrait medallion of Fawcett by Mary Grant.

On the other side of the path is a statue of Robert Raikes (1736–1811), a newspaper proprietor from Gloucester who is often considered to be the founder of Sunday Schools. In fact, he did not set up the first school, but was very active in promoting them, leading to the creation of the Sunday School Society in 1786. In July 1880, during the Sunday School centenary celebrations, the bronze statue, by Thomas Brock, was unveiled by the Earl of Shaftesbury. Raikes is portrayed in eighteenth-century clothes, pointing at a Bible in his left hand. In 1930 two replicas were made of the statue, which now stand in Gloucester, Raikes’s birthplace, and in Toronto.

Raikes holds a Bible, a reminder of his work in promoting Sunday Schools.

The semi-nude figure on Sullivan’s memorial symbolises grief-stricken Music.

A memorial to Sir Arthur Sullivan (1842–1900) is nearby. Sullivan is best known for the comic operas he composed in partnership with W. S. Gilbert, but he composed much else, including a symphony, choral works and songs such as ‘The Lost Chord’, which made him both popular and rich, though they are rarely performed today. The memorial, the work of Sir William Goscombe John, was unveiled in 1903 by Princess Louise, Duchess of Argyll. A bust of the composer sits on a pillar, and on one side are lines from The Yeoman of the Guard:

Is life a boon?

If so it must befall

That death whene’er he call

Must call too soon.

Against the pillar reclines a semi-nude bronze female figure representing griefstricken Music, considered by some to be the most erotic sculpture in London. Around the base, also in bronze, are musical instruments, a music score and the mask of comedy. The commission was for a bust only, but the sculptor added the female figure to make the memorial more striking, which it certainly is.

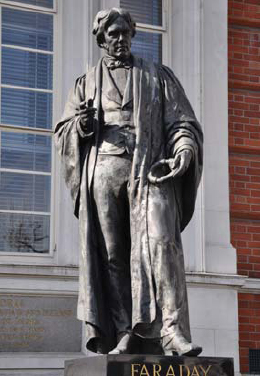

The statue of the great scientist Faraday is a copy of an original in the Royal Institution.

Walter Besant is, unusually, shown wearing glasses.

On the corner of Savoy Street and Savoy Place, in front of the Institute of Electrical Engineers, is a statue of Michael Faraday (1791–1867), the famous experimental scientist whose most important discoveries related to electricity. He wears the gown of Doctor of Civil Law of Oxford, and holds the coil with which he created the first magnetoelectric spark. The statue is a copy of a marble statue of 1874 by John Foley, which stands in the Royal Institution in Albemarle Street, where Faraday carried out many of his experiments.

On the riverside wall, almost opposite, is a bronze plaque to Sir Walter Besant (1836–1901), writer, London historian and campaigner for authors’ rights. The Society of Authors, which he helped to found, arranged for this copy of the memorial in St Paul’s Cathedral to be placed here in 1904. It is by Sir George Frampton, and the relief portrait is the first in London to wear spectacles.

Beyond Waterloo Bridge in Temple Place is a statue of Isambard Kingdom Brunel (1806–59), one of the greatest engineers of the nineteenth century. His London legacy includes the Thames Tunnel, built with his father, Marc, and now used by the London overground railway; Paddington Station; and Hungerford Bridge, a pedestrian bridge that was converted into a railway bridge. He is best remembered for the Clifton Suspension Bridge in Bristol, which was completed after his death. The statue, by Baron Marochetti, was one of three statues of engineers he created in the 1860s to be erected in the churchyard of St Margaret’s, Westminster, but his plans were rejected, and the statue of Brunel was erected here in 1877 (his statue of Robert Stephenson is now at Euston Station (see page 179). The pedestal and background were designed by Richard Norman Shaw.

Marochetti’s statue of Brunel stands in Temple Place.

Forster, though little known today, was an important reformer of the British education system.

In the quiet gardens to the east of Temple Station are three of London’s esser-known memorials. The first is to William Edward Forster (1818–86), a politician whose claim to fame was the introduction of a national system of elementary education. He also worked for the abolition of slavery with his uncle, Thomas Fowell Buxton, whose memorial stands in Victoria Tower Gardens (see page 40). The statue, by Henry Richard Hope-Pinker, was unveiled in 1890, in front of what were then the offices of the London School Board, of which Forster could be considered to be the founder.

On the other side of the path is the charming memorial fountain to Lady Henry Somerset (1851–1921), in the form of a young girl, who represents Temperance, holding a bowl that doubles as a bird bath. Lady Somerset was an advocate of temperance and a campaigner for women’s rights. In 1890 she became President of the British Women’s Temperance Movement, and the statue, by G. E. Wade, was put up in 1897. The figure of the girl was stolen in 1970, but was replaced in 1999 with a copy by Philomena Davidson Davis.

This charming drinking fountain commemorates the social reformer, Lady Henry Somerset.

John Stuart Mill sits in contemplation under the trees.

At the end of the gardens is a statue of John Stuart Mill (1806–73), the celebrated economist and philosopher. John Foley was commissioned to produce a bronze statue, but he died before starting work, and the task was entrusted to Thomas Woolner, who was one of the original members of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood. The location was chosen because of its close proximity to the offices of the London School Board, and it was unveiled in 1878. Mill is portrayed sitting, deep in thought, with a portfolio under his feet and a book in his hand.

The campaigning journalist, W. T. Stead, has a memorial on the wall of the Embankment.

The National Submarine War Memorial on the river wall of the Embankment.

On the Embankment wall opposite is a bronze plaque commemorating William Thomas Stead (1849–1912), a controversial and outspoken journalist whose concerns included the defence of civil liberties and women’s rights. While running the Pall Mall Gazette, he had a series of sensational scoops and was once imprisoned because of his unorthodox methods of obtaining information for an article on white slavery. He died on the Titanic, and was last seen helping women and children into a lifeboat. The bronze memorial by George Frampton, installed in 1920, has a relief portrait, with figures of Fortitude and Sympathy to left and right.

Nearby is the National Submarine War Memorial, a large bronze plaque in memory of those who lost their lives in submarines during the two world wars. The work of sculptor Frederick Brook because of its close proximity to the offices Hitch, and designed by the architect A. H. Ryan Tenison, it was unveiled in 1922. A new inscription was added in 1959 to include those who died in the Second World War. The central relief shows the control room of a submarine, with swimming nereids on either side. To left and right are figures of Truth and Justice. There is much marine symbolism, including dolphins and anchors, and at the bottom is a relief of a submarine on the surface. The names of submarines lost in the two wars are listed on both sides. On the walls on either side are forty small anchors used for hanging wreaths.