The Hand of God or Somebody

A WEEK AFTER the death of the hangman, William Marwood, in September 1883, the following notice appeared in the national press:

In consequence of the numerous applications which have been received at the Home Office for an appointment to the place of public executioner, we are requested to state it is neither the right nor the duty of the Secretary of State to make any such appointments. There is no such office as that of public executioner appointed by the Government. The person charged with the execution of capital sentences is the Sheriff. It is the right and the duty of the Sheriff to employ and to pay a fitting person to carry out the sentence of the law.

Among the wrongly addressed applications were these:

I, H– R–, of Trindley Colliery, County of Durham, 6 feet 1 inch in my stocking feet, 14 stone weight, 35 years of age, would like the office of public executioner, in place of the late Marwood, deceased. I would hang either brothers or sisters, or anyone else related to me, without fear or favour.

Dere Sir,

I am waiting outside with a coil of rope, and should be glad to give you a personal proof of my method.

Sir,

… I have some knowledge of Anatomy, am an exceedingly strong man, and can command sang-froid under any circumstances. I have witnessed Executions among all nations; consequently, there is no fear of my getting sick at the right moment.

Sir,

… I beg to state that by trade I am a Barber, and that my age is 34, and also that helth and nerve is good. In my Line of Business as a Barber I have had some years of Great Experience in the Formation of the necks and windpipes of all kinds of people, and, therefore, I think that the Situation, if dear Sir, it will be your Pleasure to appoint Me, would be the means of my Fulfilling it to your full satisfaction. I can Refer you for my testimonials to several Manchester Gentlemen of High honer and Long Standing.

Deer Sur,

I am ankshus to be yure publick exechoner, and i hereby apply for the job. i am thurty yeres old, and am willing to hang one or two men for nothink, so as you will see how I handle the job. i am strong, brave, and fear no man, and i will hang anybody you like, to show how i can do it. i inclose photo.

Sir,

… I have at various times made some very successful experiments in the art of hanging (by means of life-size figures) with the view to making myself thoroughly proficient in the despatch of criminals, and I have no hesitation in saying that I believe my system would be the most expeditious, never failing, and most humane that has ever been adopted or that could possibly be used, as it has been my greatest study. My system of hanging is not a lingering death by strangulation, but instantaneous and painless, rendered so by a small appliance of my own for the instant severing of the spinal cord. I may say that I adopt a variety of drops, varying from 7ft 10½ins to 16ft 11 ins. I shall be glad to conduct a series of experiments under your personal inspection on the first batch of criminals for execution, that you may see for yourself the superiority of my system over that of all others.

ins. I shall be glad to conduct a series of experiments under your personal inspection on the first batch of criminals for execution, that you may see for yourself the superiority of my system over that of all others.

All of those letters, and the hundred or so others that also shouldn’t have been sent to the Home Office, were forwarded to the Guildhall, there to be added to the pile of a thousand or so correctly-addressed ones. The Sheriffs of London and Middlesex invited some thirty of the applicants to attend interviews, separately but all on the same morning, at the Old Bailey. Of those, seventeen turned up, making one of the strangest gatherings that the Old Bailey – a place often frequented by strange gatherings – had ever housed. Within two hours the seventeen hopefuls had been interviewed, three of them twice – which indicates that the least appealing of them shambled into the Sheriffs’ presence and were instantly ordered out of it.

The short-listed three were James Berry, of Bradford, Yorkshire (who, straightway after his second interview, wrote home, saying that he had ‘virtually’ been offered the job and had ‘agreed upon the price’); Jeremy Taylor, of Lincoln, a builder who claimed to have been ‘very intimate with the late Mr Marwood’; and Bartholomew Binns, a coal-miner near his native-town of Gateshead.

The Sheriffs chose Binns – and soon wished they hadn’t. Having bungled three of the first four jobs he was given, he turned up for the fifth too drunk to be allowed near the scaffold, and was fired. It was subsequently reported that ‘Binns, piqued at his dismissal, obtained a wax figure and a small gibbet, and appeared at fairs, etc, etc, exhibiting in a booth the manner in which he had carried out the executions during his short tenure of office. The police soon put a stop to his disgraceful exhibitions, and Mr Binns dropped out of the public sight.’

In 1884, James Berry, so recently rejected, was instated. The long-standing executioner, William Calcraft, had in his youth made shoes; Marwood throughout his life had mended them; and the footwear association was continued by Berry, who, having spent most of his twenties as a constable in the Bradford and West Riding police force, had become a seller of shoes in someone else’s shop – a job that he did not give up till he felt secure as an executioner. Berry was less poorly educated than his predecessors: his handwriting was legible, he read unstumblingly (demonstrating that ability while conducting Methodist services as a lay-preacher), and, as the following extract from his memoirs shows, he was quite – only quite – good at sums:

I was slightly acquainted with Mr Marwood before his death, and I had gained some particulars of his method from conversation with him; so that when I undertook my first execution [on 31 March 1884], at Edinburgh, I naturally worked upon his lines. This first commission was to execute Robert Vickers and William Innes, two miners, who were condemned to death for the murder of two gamekeepers. The respective weights were 10 stone 4lb and 9 stone 6 lb, and I gave them drops of 8ft 6in and 10ft respectively. In both cases death was instantaneous, and the prison surgeon gave me a testimonial to the effect that the execution was satisfactory in every respect.

Upon this experience I based a table of weights and drops. Taking a man of 14 stone as basis, and giving him a drop of 8ft, which is what is thought necessary, I calculated that every half-stone lighter weight would require a two inches longer drop, and the full table as I entered it in my books at the time, stood as follows:

| 14 stone | … | … | … | … | 8ft | Oin |

| 13½ | … | … | … | … | 8 | 2 |

| 13 | … | … | … | … | 8 | 4 |

| 12½ | … | … | … | … | 8 | 6 |

| 12 | … | … | … | … | 8 | 8 |

| 11½ | … | … | … | … | 8 | 10 |

| 11 | … | … | … | … | 9 | 0 |

| 10½ | … | … | … | … | 9 | 2 |

| 10 | … | … | … | … | 9 | 4 |

| 9½ | … | … | … | … | 9 | 6 |

| 9 | … | … | … | … | 9 | 8 |

| 8½ | … | … | … | … | 9 | 10 |

| 8 | … | … | … | … | 10 | 0 |

This table I calculated for persons of what I might call ‘average’ build, but it could not by any means be rigidly adhered to with safety.

That last comment of Berry’s was an understatement. By the start of 1886 his percentage of ‘mishaps’ – though slightly lower than Marwood’s, and nowhere near Binns’s seventy-five per cent – was considered by the Home Secretary to be high enough to warrant the appointment of a Departmental Committee, under the chairmanship of Lord Aberdare, its brief ‘to inquire into the existing practice as to carrying out of sentences of death, and the causes which in several recent cases have led either to failure or to unseemly occurrences; and to consider and report what arrangements may be adopted (without altering the existing law) to ensure that all executions may be carried out in a becoming manner without risk of failure or miscarriage in any respect’. The Committee recommended, inter alia, that all scaffolds should be much alike and that the ropes should be of standard thickness and length, and proposed a ‘scale of drops’ that differed in some respects from the one worked out by Berry.

None of Berry’s ‘subjects’ was as famous beforehand as was one of them, John Lee, afterwards – his fame being chiefly due to the fact that he was able to savour it. Lee, having been found guilty of the stabbing to death of Emma Keyse, the sixty-eight-year-old spinster for whom he had worked domestically in the suburb of Torquay called Babbacombe, was scheduled to die in Exeter Prison at eight o’clock on the morning of Monday, 23 February 1885. But, depending upon which way one looks at it – from Lee’s point of view or from Berry’s – things went miraculously right or embarrassingly wrong. Berry gave his version of the non-event in a replying letter, dated 4 March, to the Under-Sheriff of Devon (who seems to have confused him, perhaps by allotting thirty days to February, into writing inst, then ult, rather than ult twice):

Sir,

In accordance with the request contained in your letter of the 30th inst, I beg to say that on the morning of Friday, the 20th ult, I travelled from Bradford to Bristol, and on the morning of Saturday, the 21st, from Bristol to Exeter, arriving at Exeter at 11.50 am, when I walked direct to the County Gaol, and signed my name in your Gaol Register Book at 12 o’clock exactly. I was shown to the Governor’s office, and arranged with him that I would go and dine and return to the Gaol at 2.0 pm. I accordingly left the Gaol, partook of dinner, and returned at 1.50 pm, when I was shown to the bedroom allotted to me, which was an officer’s room in the new Hospital Ward. Shortly afterwards I made an inspection of the place of Execution. The execution was to take place in a Coach-house in which the Prison Van was usually kept…. Two Trap-doors were placed in the floor of the Coach-house, which is flagged with stone, and these doors cover a pit about 2 yards by 1½ yards across, and about 11 feet deep. On inspecting these doors I found they were only about an inch thick, but to have been constructed properly should have been three or four inches thick. The ironwork of the doors was of a frail kind, and much too weak for the purpose. There was a lever to these doors, and it was placed near the top of them. I pulled the lever and the doors dropped, the catches acting all right. I had the doors raised, and tried the lever a second time, when the catch again acted all right. The Governor was watching me through the window of his office and saw me try the doors. After the examination I went to him, explained how I found the doors, and suggested to him that for future executions new trap-doors should be made about three times as thick as those then fixed. I also suggested that a spring should be fixed in the Wall to hold the doors back when they fell, so that no rebounding occurred, and that the ironwork of the doors should be stronger. The Governor said he would see to these matters in future. I retired to bed about 9.45 that night….

On the Monday morning I arose at 6.30, and was conducted from the Bedroom by a Warder, at 7.30, to the place of execution. Everything appeared to be as I had left it on the Saturday afternoon. I fixed the rope in my ordinary manner, and placed everything in readiness. I did not try the Trap-doors as they appeared to be just as I had left them. It had rained heavily during the nights of Saturday and Sunday. About four minutes to eight o’clock, I was conducted by the Governor to the Condemned Cell and introduced to John Lee. I proceeded at once to pinion him, which was done in the usual manner, and then gave a signal to the Governor that I was ready.

The procession was formed, headed by the Governor, the Chief Warder, and the Chaplain followed by Lee. I walked behind Lee and six or eight warders came after me. On reaching the place of execution I found you were there with the Prison Surgeon. Lee was at once placed upon the trapdoors. I pinioned his legs, pulled down the white cap, adjusted the Rope, stepped to one side, and drew the lever – but the trap-door did not fall. I had previously stood upon the doors and thought they would fall quite easily. I unloosed the strap from his legs, took the rope from his neck, removed the White Cap, and took Lee away into an adjoining room until I made an examination of the doors. I worked the lever after Lee had been taken off, drew it, and the doors fell easily. With the assistance of the warders the doors were pulled up, and the lever drawn a second time, when the doors again fell easily. Lee was then brought from the adjoining room, placed in position, the cap and rope adjusted, but when I again pulled the lever it did not act, and in trying to force it the lever was slightly strained. Lee was then taken off a second time and conducted to the adjoining room.

It was suggested to me that the woodwork fitted too tightly in the centre of the doors, and one of the warders fetched an axe and another a plane. I again tried the lever but it did not act. A piece of wood was then sawn off one of the doors close to where the iron catches were, and by the aid of an iron crowbar the catches were knocked off, and the doors fell down. You then gave orders that the execution should not be proceeded with until you had communicated with the Home Secretary, and Lee was taken back to the Condemned Cell. I am of opinion that the ironwork catches of the trap-doors were not strong enough for the purpose, that the woodwork of the doors should have been about three or four times as heavy, and with ironwork to correspond, so that when a man of Lee’s weight was placed upon the doors the iron catches would not have become locked, as I feel sure they did on this occasion, but would respond readily. So far as I am concerned, everything was performed in a careful manner, and had the iron and woodwork been sufficiently strong, the execution would have been satisfactorily accomplished.

As likely an explanation for the failure of the apparatus appears in a book entitled In the Light of the Law (London, 1931), the author of which, Ernest Bowen-Rowlands, quotes a letter from a ‘well-known person’ who claimed to have heard from someone that

an old lag in the gaol confessed to him (I think when dying) that he was responsible for the failure of the drop to work in the execution of the Babbacombe murderer. It appears that in those days it was the practice to have the scaffold erected by some joiner or carpenter from among the prisoners. The man inserted a wedge which prevented the drop from working and when called in as an expert he removed the wedge and demonstrated the smooth working of the drop, only to re-insert it before Lee was again placed on the trap. This happened three times [only twice, according to Berry] and finally Lee was returned to his cell with doubtless a very stiff neck.

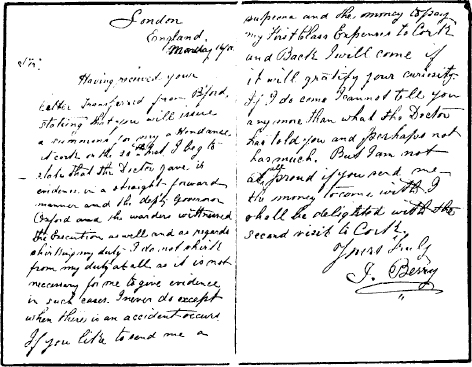

Berry’s failure to hang Lee was the most markedly imperfect of his several imperfect performances. Three years after that debacle, on Tuesday, 10 January 1888, a superstition that he had inherited from his predecessor, William Marwood – that it was bad luck on someone, presumably other than a convicted murderer, for a murderer to be hanged when he was facing east – caused a breach of executional etiquette in the despatching of Philip Cross, an Army surgeon retired to the south of Ireland, who had used arsenic to murder his wife so as to be free to marry Effie Skinner, the governess of two of his five children. When Cross was brought to the gallows in Cork Prison, he insisted on facing the Governor and the rest of the witnesses, all of whom he knew socially – and who were gathered to the east of him. After two or three attempts to get him facing in any other direction, Berry scolded him: ‘This just won’t do, Dr Cross – you have to die facing the same way as anyone else.’ He turned him north or south; Cross at once turned back to the east; the Governor, not knowing what all the directional fuss was about, exclaimed: ‘Leave the doctor alone’ – and Berry, cross himself by now, didn’t wait for the chaplain to say anything before pulling the lever, letting Cross down with a lurch, and giving the chaplain, left teetering on the brink, a nasty shock. Not till the subsequent inquest, when the coroner said that he wanted to question Berry about his pre-prayer pulling of the lever, was it learned that he, with his wife and two minding detectives, had gone off in a huff. There was ‘something of a brawl’ between the coroner and the attending Deputy-Governor, a Mr Oxford, in which members of the jury who wanted Home Rule for Ireland joined in, and the inquest was adjourned till the next day – when, despite the prison surgeon’s reminder that Cross could not be buried while the inquest was ‘in continuance’, the coroner insisted that Berry be brought back from England, and adjourned the inquest indefinitely. A letter sent to Berry’s home in Bradford was posted on to where he was staying in London, and he retaliated with the letter reproduced above (its grammatical and spelling errors indicate that the letter to the Under-Sheriff of Devon re John Lee [page 131] was either composed on Berry’s behalf or copy-edited prior to its publication). The Governor had no power to issue a ‘supeona’, and no wish to increase the cost of the execution by paying Berry a second lot of ‘First Class Expenses to Cork and Back’. Though the Lord Lieutenant eventually gave an order for the burial, the inquest remained adjourned – and is still adjourned … which means that Dr Philip Cross, hanged impatiently more than a century ago, is, in the eyes of the law, not yet deceased.

There is, I must say of course, another possibility: Divine Intervention. Though Berry stuck to his worldly explanation, other non-conforming preachers sermonised that God, in his mercy, had locked the jaws of death on behalf of Lee. But considering that Lee (who had served a sentence for theft) was undoubtedly guilty of the extremely brutal murder of an especially God-fearing old lady, it is hard to comprehend why He should have chosen to interfere, apparently uniquely, in this case. The ‘hand of God’ theory seems less credible than a ‘hand of Satan’ one.

The Home Secretary, deciding that it would be unfair on Lee to put him through further attempts to hang him, granted a reprieve. In his case, ‘imprisonment for life’ amounted to twenty-three years. Following his release in December 1907, he did quite well from ‘The Man They Could Not Hang’ stories in newspapers, the longest of which was turned into a paperback.1

Berry was only forty when he resigned in March 1892. He stated that his decision was solely ‘on account of Dr Barr interfering with my responsible duty at Kirkdale Gaol, Liverpool, on my last execution there’ (of a man named John Conway, who had been almost decapitated). As that unfortunate incident had occurred nearly seven months before, either Berry was in the throes of a delayed psychological reaction or he used the incident as an excuse for resigning. The latter possibility is strengthened by two facts: shortly after becoming an ex-executioner, he became the first such man to publish a book of memoirs2, and shortly after the book appeared, he embarked upon a long lecture-tour, for which he was very well paid. Though there was nothing in his book that suggested that he disapproved of capital punishment, his lecture was a mixture of the ‘Exciting Episodes’ promised on the billboards, and passages of abolitionist propaganda. I noted in the introduction to the facsimile edition of the book, published in 1972, that ‘when the lecture engagements petered out, Berry turned his hand to various jobs: as well as being an innkeeper, he was at another time a cloth salesman at north-country markets, at another a bacon salesman on commission. The last years of his life were devoted to evangelistic and temperance work, and he died at his home in Bradford in October 1913.’

1. There is a recording (Island: ILPS 9176) of an almost musical version of the Lee legend, mostly composed by a pop-group called Fairport Convention, who are entirely responsible for singing and playing it.

2. My Experiences as an Executioner (Percy Lund & Co, Bradford and London, n.d.; facsimile edition [edited and introduced by Jonathan Goodman], David & Charles, Newton Abbot, and Gale Research, Detroit, 1972.)

Postscript

Here are five reports of public executions (three in London, one in Cork, and one in Columbia, Mississippi) which failed to meet the ‘hang by the neck till dead’ legal requirement.

From the Gentleman’s Magazine, London, April 1733:

Four of the seven malefactors who received sentence of death at the Old Bailey on the 7th were executed at Tyburn on the 27th, viz, W. Gordan, James Ward and W. Keys for robbery on the highway and W. Norman for a street robbery. The other three, viz, H. Harper and Samuel Elms for street robberies and Elizabeth Austen for robbing her mother, who pleaded her belly and was found pregnant, were ordered to be transported for fourteen years. ’Twas reported that Gordan cut his throat just before he was carried out of Newgate for execution and a surgeon sewed it up, but in the Daily Advertiser we have the following strange account:

Mr Chovet, a surgeon, having by frequent experiments on dogs discovered that opening the windpipe would prevent the fatal consequences of the halter, undertook Mr Gordan and made an incision in his windpipe, the effect of which was that when Gordan stopped his mouth, nostrils and ears for some time, air enough came through the cavity to continue life. When he was hanged, he was perceived to be alive after all the rest were dead, and when he had hung three-quarters of an hour, being carried to a house in Tyburn road, he opened his mouth several times and groaned, and, a vein being opened, he bled freely but shortly died.

’Twas thought that if he had been cut down five minutes sooner, he might have recovered.

From the Gentleman’s Magazine, July 1736:

The grand jury for the county of Middlesex found a bill of indictment against James Bayley and Thomas Reynolds under the Black Act for going armed and disguised and cutting down Ledbury Turnpike. On 9 April 1736, William Bithell and William Morgan were tried for the same offence and hanged. During the trial their fellow turnpike levellers turned up and became so tumultuous that soldiers were called out to preserve order.

Reynolds, a turnpike leveller, condemned with Bayley on 10 April, under the act against going armed and disguised, was hanged at Tyburn on 26 July. He was cut down by the executioner as usual, but as the coffin was being fastened, he thrust back the lid, upon which the executioner would have tied him up again, but the mob prevented it and carried him to a house. There he vomited three pints of blood, but when given a glass of wine he died. Bayley was reprieved.

From the London Magazine, November 1740:

Five malefactors were executed at Tyburn on 24 November, viz, Thomas Clark, William Meers, Margery Stanton, Eleanor Mumpman for several burglaries and felonies, and William Duell for ravishing, robbing and murdering Sarah Griffin at Acton. The body of Duell was brought to Surgeons Hall to be anatomised, but after it was stripped and laid on the board and one of the servants was washing him in order to be cut, he perceived life in him and found his breath to come quicker and quicker, on which a surgeon took some two ounces of blood from him. In two hours he was able to sit up in his chair and groaned very much and seemed in great agitation but could not speak. He was kept at Surgeons Hall until twelve o’clock at night, the sheriff’s officers, who were sent for on this extraordinary occasion, attending. He was then conveyed to Newgate to remain there until he be proved to be the very identical person ordered for execution on the 24th. The next day he was in good health in Newgate, ate his victuals heartily, and asked for his mother. Great numbers of people resorted continually to see him. He did not recollect being hanged but said he had been in a dream.

At the next session at the Old Bailey, he was ordered transported for life.

From the Gentleman’s Magazine, February 1767:

One Patrick Redmond, having been condemned at Cork in Ireland to be hanged for a street robbery, he was accordingly executed on 24 February, and hung upwards of twenty-eight minutes, when the mob carried off the body to a place appointed, where he was, after five or six hours, actually recovered by a surgeon who made an incision in his windpipe called bronchotomy, which produced the desired effect. The poor fellow has since received his pardon and a genteel collection has been made for him.

The next account – of incidents in Columbia, Mississippi,1 on 7 February 1894 – needs an introduction, and that is well provided by August Mencken in his book By the Neck:1 ‘Some years after the original Ku Klux Klan went out of existence, a similar organisation called the White Caps was formed in the remoter parts of the South for the purpose of terrorising the Negroes. Its members rode round the country at night dressed in white sheets smeared with red paint to simulate blood, but for the most part they confined themselves to threats and resorted to violence only in what they considered extreme cases. Early in 1893, a Negro servant of Will Buckley, a member of the organisation, was selected for such treatment, and, in the absence of Buckley and without his knowledge, one of the bands seized the man and gave him a flogging. Buckley was enraged at this affront to his dignity, and for revenge decided to present the whole matter to the Grand Jury. As a result of his disclosures, three members of the gang were indicted. After completing his testimony, Buckley started for home accompanied by his brother Jim and the Negro, all mounted. When they came to a ford in a small stream, someone concealed in the underbush shot and killed Will Buckley. The other two were fired on also, but escaped. The scene of the killing was near the home of a family called Purvis, and as Will Purvis, one of the sons, was generally believed to be a member of the White Caps, a neighbour who had a grudge against the family had little difficulty arousing the neighbourhood against the boy. Purvis was arrested and lodged in jail. At his trial, he produced witnesses who testified that he was nowhere near the scene at the time of the murder, but Jim Buckley, who had witnessed the killing, was positive in his identification of Purvis as the man who had shot his brother, so Purvis was found guilty by the jury and sentenced to hang.’

1. There seems to be uncertainty concerning the date of the last official public hanging in Mississippi. Though the hanging of Clyde Harveston, at Westville, in 1902, was not the last, it warrants being mentioned in this book because of a perhaps supernatural adjunct to it. Apparently, Harveston was found guilty of the murder of a merchant, Frank Ammons, solely because an erstwhile friend, Frank Beavers, implicated him when confessing to the crime; Beavers died naturally a few days after the trial. Harveston protested his innocence till the end, and went so far as to shout, as the noose was tightened: ‘God will give you a sign that I am telling the truth!’ Though the day is said to have been cloudless, rain started pelting down during the brief period between Harveston’s prophesy and his fall. Those who believe that the rain was a ‘sign’ rely upon a photograph of the execution, which shows a number of opened umbrellas above the crowd – but as the photograph also shows Harveston still erect, it may have been taken before his shout … and, of course, one is perplexed as to why so many spectators carried umbrellas on a cloudless day.

Perhaps the last public hanging in Mississippi was of Will Mack, a negro, at Brandon, near the state capital of Jackson, on Thursday, 23 July 1909: a sweltering day, according to the Brandon News, ‘with a thrifty trucker selling large, juicy, red-meated watermelons to those who wished something cooling, and the peanut vendor, the ice cream cone seller and the pop-stand fellow doing a rushing business … to a crowd that had no reason to be other than good-humoured about the hanging of a criminal whose death every decent person in the world said should be the penalty of rape. Some ladies were present; many little children, some with parents – and others without, as they were large enough to keep from being mashed in the crowd; there were a few nursing infants who tugged at the mother’s breasts while the mother kept her eyes on the gallows – she didn’t want to lose any part of the programme she had come miles to see – to tell about to the neighbours at home who were unable to be on hand – to think about while awake; to doubtless see in horrible dreams when asleep, and to never want to see again.’ But Will Mack’s may not have been Mississippi’s ‘last necktie party’. That term headlined a letter from an Ernest Ishee that was published in the Jackson Clarion Leader of 6 August 1979: ‘… I wish to inform you that the execution of Will Mack at Brandon in 1909 was not the last public hanging in the state. There was one in Bay Springs in 1912 or 1913. My father and two older brothers went to the event.’

1. Hastings House, New York, 1942.

From the New Orleans Item:

Purvis’s hour approaches. The scaffold, firm and portentous, has been erected on the courtyard square; the rope has been secured, the knot tied and examined by a committee. The black cap, symbol of death, is ready. The people gather and struggle for points of vantage. The minister is praying and consoling the boy the best he can. The death march begins.

With face bleached by confinement within prison walls, but with a firm step and steady eye, young Purvis ascends the scaffold. As he looks over that closely packed and vacuously yawping throng, the young man sees few friendly faces. Feeling against him has been intense and most people believe he is about to expiate a crime for which he should pay the extreme penalty. Everyone is waiting for one thing before the final drop. It is the confession of the boy that he did commit murder. But Purvis speaks simply these plain words which amaze them:

‘You are taking the life of an innocent man. There are people here who know who did commit the crime, and if they will come forward and confess, I will go free.’

As Purvis finishes his simple plea, the sheriff and three deputies adjust the rope about his neck, his feet and arms are pinioned, and the black cap is placed over his face. All is ready, but the meticulous deputy who has tied the hangman’s knot sees an ungainly rope’s end sticking out. One must be neat at such functions, and he steps up and snips the end flush with the knot. ‘Tell me when you are ready,’ Purvis remarks, not knowing that the doomed is never given this information lest he brace himself.

Nothing is heard save the persistent and importunate prayer of the minister. The executioner takes the hatchet. As he draws it back to sever the stay rope holding the trap on which Purvis stands, strong men tremble and a woman screams and faints. The blow descends, the trap falls, and the body of Will Purvis darts like a plummet towards the sharp jerk of a sudden death.

Terror and awe gripped the throng as Purvis fell towards his death. Those few men who had watched others hang averted their faces. Others who had never witnessed a like event, and who could not appreciate the morbid horror of it, stared open-mouthed. But those who looked did not see the boy dangle and jerk and become motionless in death. The rope failed to perform the service ordained for it by law. Instead of tightening like a garroter’s bony fingers on the neck of the youth, the hangman’s knot untwisted and Purvis fell to the ground unhurt save for a few abrasions on his skin caused by the slipping of the rope.

No tongue can describe and no pen can indite the feeling of horror that seized and held the vast throng. For a moment the watchers remained motionless; then, moved by an impelling wonder, they crowded forward, crushing one another with the force of their movement. In a moment the silence broke. Excited murmurs began to emanate from the crowd. ‘What’s the matter? Did the noose slip?’ someone asked. Others wondered if there had been some trick in tying the knot. But those charged with the duty of making it fast said there was not, and their statement was verified by a committee that had examined the rope and the knot just before its adjustment around the man’s neck.

Besides, there could hardly have been a desire on the part of any of the officials to save Purvis. The organisation with which he was supposed to have been connected had given them too much trouble and his trial and conviction had cost the county too much money to warrant the belief that any means would have been used at that late hour to circumvent the execution of the death sentence.

Somewhat dazed, Purvis staggered to his feet. The black cap slipped from his face and the large blue eyes of the boy blinked in the sunlight. Most of the crowd stood dumbfounded and the officials were aghast. Purvis realised the situation sooner than any of them and, turning to the sheriff, said, ‘Let’s have it over with.’ At the same time the boy, bound hand and feet as he was, began to hop towards the steps of the scaffold and had mounted the first step before the silence was broken.

An uneasy tremor swept the crowd. The slight cleavage in opinion which before had been manifest concerning the boy’s guilt or innocence now seemed to widen into a real division. Many of those who had been most urgent that Purvis be hanged began to feel within themselves the first flutter of misgiving. This feeling might never have been crystallised into words had it not been for a simple little incident. One of the officials on the platform had reached for the rope but found it was just beyond his fingers’ ends. Stooping, he called out to Dr Ford, who was standing beneath, ‘Toss that rope up here, will you, Doctor?’ Dr Ford started mechanically to obey. He picked up the rope and looked at it. The crowd watched him intently. Here was a man who had been most bitter against the White Caps, a man who knew that Purvis had been a member of that notorious body, and yet everyone knew that he was one of the few who refused to believe the boy was guilty. Throwing the rope down, he said, ‘I won’t do any such damn thing. That boy’s been hung once too many times now.’

Electrically, the crowd broke its silence. Cries of ‘Don’t let him hang!’ were heard clashing with ‘Hang him! He’s guilty!’ A few of Purvis’s friends and relatives were galvanised into action. They pushed their way forward, ready to act, but the greater proportion of the spectators were still morbidly curious to see the death struggles of the boy. Some of them really believed the ends of justice were about to be thwarted and tensed themselves to prevent any attempt to free him.

At this moment the Reverend J. Sibley, whose sympathy and prayer had helped to sustain the mother during her trying ordeal, sprang up the steps of the scaffold ahead of the stumbling boy. He was a preacher of the most eloquent type and of fine physique and commanding appearance. His eyes flashed with the fire of a great inspiration as he raised his hands and stood motionless until the eyes of the spectators became centered upon him. ‘All who want to see this boy hanged a second time,’ he shouted, ‘hold up their hands.’

The crowd remained transfixed. There is a difference between the half-shamed desire of a man to stand in a large throng and watch his neighbour die and the willingness of that man to stand before others and signify by raising his hand that he insists upon the other’s extinction. Not a hand went up. ‘All who are opposed to hanging Will Purvis a second time,’ cried the Reverend Sibley, ‘hold up your hands.’ Every hand in the crowd went up as if magically raised by a universal lever.

Pandemonium ensued. Men tore their hair and threw their hats into the air, swearing that this man should not be hanged again. Public sentiment had changed in an instant. Before the hanging, they thought him a vile and contemptible murderer; now they believed him spotless as an angel. But even while the mob was joyously acclaiming Purvis as one returned from the shadow of death, and men and women were surging forward to congratulate him on his miraculous escape, the menace of the law still hung over him, reluctant to allow him to escape.

The sheriff and his deputies were undoubtedly in an awkward position. They had been commissioned to carry out the sentence of the court and they were bound by their oaths of office to do so. Should they flout the authority of the court merely because a number of emotional spectators had decided out of hand not to allow the defendant to be hanged, they would be liable to impeachment and imprisonment. On the other hand, to attempt to hang Purvis the second time in the face of 5000 healthy spectators, nearly every one determined to prevent such action, would be suicidal.

It was clearly an unusual situation and one which called for the finely balanced judgment of a legally trained mind. The sheriff turned to Dr Ford and said, ‘These folks do not want to see Purvis hanged again, Doctor, but I am bound in honour to carry out the sentence of the court. Because the rope slipped I can’t see that the situation is altered. What do you think?’

Dr Ford suggested that a judge or lawyer be sought. The sheriff called for a judge, but none was in the crowd. Then he asked for lawyers, and for a moment it seemed that the lawyers had also decided not to attend the execution; but finally a young attorney answered the summons. After considering the matter in its various apsects, he reluctantly informed the sheriff that it was his belief that Purvis must be ‘hanged by the neck until dead’, according to the meaning of the sentence. The sheriff as reluctantly agreed.

Meanwhile, activity had been resumed upon the scaffold by the executioners. The crowd had quieted and waited to hear the results of the conference, which took place near the scaffold. The sheriff looked at the throng. Its temper was probably heated, so that an attempt to hang Purvis again might result in additional tragedy, yet he did not see how he could avoid making the attempt at least. Dr Ford, who had listened with chagrin to the attorney’s opinion, finally spoke up with determination. ‘I don’t agree with you. Now, if I go upon that scaffold and ask three hundred men to stand by me and prevent the hanging, what are you going to do about it?’

Both the sheriff and the attorney were taken aback at this suggestion. They realised that they would be powerless in the face of such action. ‘I’m ready to do it too,’ added Dr Ford. Suddenly the sheriff turned, walked to Purvis, and as the crowd cheered, began to loosen the bonds of the prisoner. Dr Ford, fearing he would release Purvis, interfered. ‘Don’t let him go,’ he said. ‘Take him back to his cell.’ Dr Ford was afraid that if Purvis was released, the White Caps would assume a more important place in the minds of several citizens than the courts, that the murder of Buckley would be condoned, and the possibility of capturing the real murderer made more remote than with Purvis in prison to await further legal action. It was with difficulty that Purvis was carried back to jail, so persistent was the crowd in its demand for his freedom.

Henry Banks, one of the staff of executioners, afterwards gave his version of why the knot had slipped. ‘The rope was too thick in the first place,’ he said. ‘It was made of new grass and was very springy. After the first man tied the noose, he let the free end hang out. It was this way when the tests were made, but when it came to placing this knot around Purvis’s neck, it looked untidy. The hangman didn’t want to be accredited with this kind of a job, so he cut the rope flush with the noose-knot. It looked neat, but when the weight of Purvis’s body was thrown against it, the rope slipped and the knot became untied.’

August Mencken: ‘After the fiasco at the scaffold, Purvis was returned to his cell and a legal battle was started to free him. His case was based on Article V of the Constitution of the United States, prohibiting double jeopardy, but the Mississippi Supreme Court decided against him and he was re-sentenced to hang. While he was awaiting execution the second time, his friends broke into the jail and carried him to a hiding-place on a remote farm. Two years afterwards, Jim Buckley changed his mind and announced that he was not sure that Purvis was the man, and in consequence the Governor commuted Purvis’s sentence to life imprisonment. The fugitive then returned from the farm and started serving his sentence, and on 19 December 1898 he received a full pardon. Nineteen years afterwards, one Joe Beard was gathered in by the Holy Rollers, and, in ridding himself of his sins, confessed, among other things, that he and one Louis Thornhill were the men who killed Buckley. The Legislature of Mississippi thereupon voted Purvis $5000 as compensation for the time he spent in jail.’