| Imp. Caesar Divi f. III | M. Antonius M. f. III | |

| suff. | M. Valerius M. f. Messalla Corvinus | |

| suff. | M. Titius L. f. | |

| suff. | Cn. Pompeius Q. f. |

It was no ordinary New Year’s Day. Something was very amiss. When Imperator Caesar Divi filius (plate 1) swore his oath as consul, the members present in the Senate House in Rome could not fail to notice that the curule chair beside his was vacant.1 In the Res Publica (the name by which the Romans proudly called their commonwealth) there should always be two consuls. It was a check and balance against the tyranny of rule by one man born of popular revolution and the overthrow of kings centuries before. This day, however, his colleague, M. Antonius (plate 5), elected to the office the previous autumn, was tarrying in Greece.

Once the younger and older man had been friends, bound in a mutual pact of vengeance. Over the months following the assassination of C. Iulius Caesar on the Ides of March 44 BCE, the two men joined with M. Aemilius Lepidus, a former commander of the deceased dictator. They were colleagues in a selfappointed commission of ‘Three Men for the Restoration of the Commonwealth’.2 Working together as triumviri, they had divided up the world among themselves, raised armies and hunted down the assassins to a mosquito-infested marsh close to Philippi and killed them in two battles; but over ten subsequent years the three men had become estranged.3 Power had seduced their better natures. Iulius Caesar’s legal heir had ambitions to be pre-eminent in Rome, and soon ousted Lepidus, but in his way was Antonius.4 Meanwhile the East had beguiled his partner in power. The perception among his enemies in Rome was that Antonius had abandoned his responsibilities as an officer of the state and turned away from the Roman People. Matters culminated when it was discovered that he had had a scandalous affair with the queen of Egypt, Kleopatra VII (plate 4), and wedded her, despite already being married – in fact to Octavia, the well-liked sister of triumvir Imp. Caesar.5 It was a personal slight to him, but not reason enough to go to war.6 The insulted brother-in-law shrewdly looked elsewhere for his casus belli. In his eagerness for glory, Antonius had led military expeditions against Parthia in Armenia – campaigns not sanctioned by the Senate but bankrolled by the Egyptian queen, and which, moreover, had spectacularly failed with great loss of Roman lives.7 Antonius had also divided up among his illegitimate children territories that properly belonged to the Roman state and that were officially due for assignment to Roman senators by lot. 8 Caesar expressed his views about these and other complaints in writing; Antonius responded in like manner.9 The letters exchanged between the two men became ever more vitriolic, finally spilling over into open hostility.

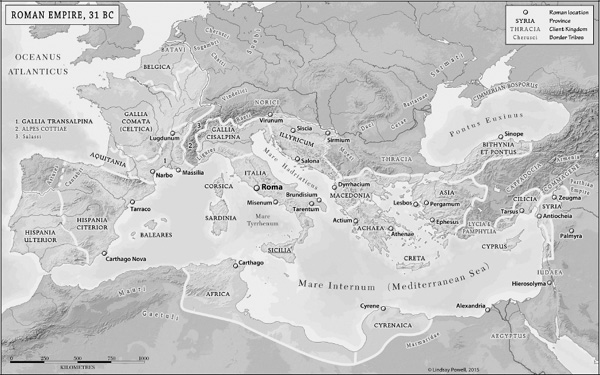

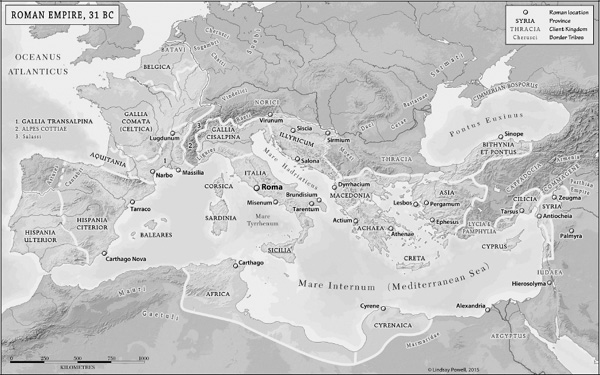

The toga-clad men sitting in the Curia Iulia that cold January day already had an idea of what lay ahead: it was to be all-out war between the adversaries for a final resolution and the future of the ‘imperium (sovereignty) of the Roman People’ (map 1). The victor would take all. Unlike his rival in the Orient, the 31-year old Imp. Caesar had wasted no time. For several months, and with consummate skill, he had been executing his strategy to win the hearts and minds of his countrymen, some with charm, others with coercion. In the spring of the previous year he had required the whole civilian population of Italy to swear the sacramentum (a military oath of allegiance to him personally), in effect amalgamating the Roman state into himself – tactfully, the members of Antonius’ hereditary family were exempted from taking it.10 Sensitive to how the public might perceive the coming struggle, Caesar sought to avoid the appearance of a conflict between fellow Roman citizens. It was the Egyptian regent who provided both the pretext and focus for Caesar’s belligerence. Finally, in October, among the charges laid against Antonius Imperator was that he had allowed himself to be seduced by a woman – and not a Roman woman, but worse, a foreigner. She had demanded the Roman Empire from the besotted, drunken triumvir, he asserted, as payment for her favours.11 It was a sham. ‘These proceedings,’ writes Dio, ‘were nominally directed against Kleopatra, but really against Antonius.’12 He was stripped of his authority.13 Now, at the age of 52, he was just a private citizen once more. He would not be consul this year – or ever again.

With his military offensive legitimated by due process of law, Imp. Caesar invoked the favour of the gods too; he was, after all, as coins and inscriptions proclaimed, Divi filius, ‘son of a god’ – specifically the divine Iulius Caesar.14 For full effect, he re-instituted an ancient rite in which a fetial, dressed in priestly garb, intoned a declaration of war, melodramatically striking an iron-tipped spear smeared with blood into a patch of ground designated enemy territory at the Temple of Bellona.15 With the sworn support of the People and the Senate, and the blessings of the Roman gods, how could Caesar now lose?

Some 1,250 kilometres (777 miles) away in Athens, and oblivious to the rapidly unfolding events in the West, Antonius still believed himself the legitimate coconsul. In his own mind he had no reason to think otherwise. Reduced in number, purged of rogues and dominated by friends of his young rival, nevertheless Antonius had many sympathisers in the Senate; they despised the arrogant young upstart who, in their view, had undeservedly inherited the dictator’s name. Over the last several years they had worked to promote Antonius’ interests while he was away from Rome, and to undermine his rival’s. It had culminated in 32 BCE when one of the year’s consuls, C. Sosius, had denounced Imp. Caesar before the Conscript Fathers.16 Caesar had not been there to face the accusations personally, but upon his return to Rome he convened a meeting of the Senate to raise the matter. In the high-ceilinged chamber, he seated himself provocatively on a chair beside the two consuls, taking the precaution of bringing loyal soldiers who had daggers concealed in the folds of their togas.17 At that extraordinary session he promised the next time they met to bring documents proving beyond a doubt Antonius’ indiscretions. He also invited any man present who felt insecure to feel free to leave the city and join his champion. Many did – some 200 of the 900 senators fled, Sosius and his co-consul Cn. Domitius Ahenobarbus among them.18 To emphasize the fact of Antonius’ public ostracism, in Rome another man was elected to take his seat. M. Valerius Messalla Corvinus was the same age as Imp. Caesar. He had already proved loyal to him in battle and was considered a colleague who could be trusted to remain loyal in politics. Corvinus would be the first of many such career advancements that year to the highest office for services rendered – or expected. The die was cast. There would be no second throw.

Map 1. The Roman Empire, 31 BCE.

The man who had brazenly taken imperator (plate 3) – meaning ‘commander’ – as his first name was no novice in war. He had personal experience of battle, and scars to prove it. Born on 23 September 63 BCE, his military career had not begun auspiciously, however. He had had the opportunity to learn first-hand from one of the greatest generals of all time when Iulius Caesar invited him as his great nephew, then just 16 years old, to join him in his campaign against the sons of Pompeius Magnus in Spain in 46 BCE. By an accident of timing, the teenage tyro had arrived too late – after the conflict had already concluded.19 The second opportunity – the chance to accompany Iulius Caesar in a war against the Getae and Parthians in 44 BCE – had ended before it had even started when the great commander was cut down on 15 March.20 But the young man quickly showed some of the promise the older relation had seen in him. A few months after the assassination, he successfully raised his own legions from among veterans who had served his great uncle and, at the Senate’s insistence, had taken them into action against the then outlaw M. Antonius at the Battle of Forum Gallorum and siege of Mutina in April 43 BCE.21 He commanded those troops against the rebel L. Antonius at Perusia (modern Perugia) in 41 BCE and at Fulginiae (Foligno) the following year, and against the renegade Sex. Pompeius in Sicily in 36 BCE.22 He had led campaigns to quell rebellions in Illyricum and shown courage when he personally led charges at the sieges of Metulus in 35 BCE and Setovia in 34 BCE, and had sustained serious injuries in the attacks.23

Yet those campaigns had also revealed to him his limitations as a field commander. He was not a tough, ‘lead from the front’ warrior like Iulius Caesar. He was not even widely regarded as a ‘man’s man’. Sex. Pompeius taunted him as effeminate and M. Antonius mocked him for having won the favour of Iulius Caesar through ‘unnatural relations’; another rumour suggested he had sold his body to one of the dictator’s commanders while in Spain.24 Of course, these allegations may have been nothing more than slanders by his enemies in an attempt to belittle him in the eyes of the public. Physically, he was considered short at 5 foot 9 inches in height, but thought handsome, with clear, bright eyes, curly blondish hair and in his comportment he carried himself gracefully.25 However, his physical health was his weakness. Suetonius reports that he was not very strong in his left hip, thigh and leg, and even limped slightly at times. 26 ‘In the course of his life,’ writes his biographer, ‘he suffered from several severe and dangerous illnesses.’27 Embarrassing for him as a general was that he frequently became sick before battle, causing him to have to be carried back to his tent to recover while the fighting raged – a fact his enemies remorselessly exploited.28

His great strengths were his deep ambition, unyielding tenacity and ruthless intelligence. He had the ability to assess complex problems, to think strategically and operate tactically – whether it was manipulating the law, political connections, public relations or religion – and he knew how and when to use war, or the threat of it, to advance his cause. He also had the foresight to know he could not fight wars on his own, and, unlike his great uncle, that when he had won he could not run the empire by himself alone.

He had one capacity that would prove increasingly important and help to account for his exceptional achievement: he could consistently pick good men as personal advisors and for command positions. Regardless of background or class, and even if they had once served his enemies, it was ability that mattered most to him. He developed this talent early in his life. In his teens he had surrounded himself with a small, tight group of friends – Iulius Caesar had even complimented him on the quality of his companions, because they were observant young men and strove to attain excellence.29 He understood the value of sound advice borne of experience. He was mentored by his great uncle, who saw potential in the young man, and in the months after his murder – when he was just 19 years old – by the commander’s own close advisers too, in particular the Jewish financier and former consul (40 BCE), L. Cornelius Balbus (Balbus the Elder), and Iulius Caesar’s private secretary and biographer, C. Oppius.30 Few men alive at the time knew the dictator’s mind so well as those two men. He had also received guidance from the foremost statesman M. Tullius Cicero (cos. 63 BCE) and his fellow triumvirs, Antonius and Lepidus – at least until he considered that advice was no longer useful. Caesar did not make friends easily, but when he did he remained stubbornly loyal to them; what he could not tolerate was betrayal.31

The events of 31 BCE would be the greatest test yet of those abilities. By the start of the new year, Caesar had his hand-picked military leadership team already in place. He had delegated overall strategic command of the anticipated war against Antonius and Kleopatra (Bellum cum Antonio et Cleopatra) to his best friend and confidant M. Agrippa (plate 2).32 With thick eyebrows, short tousled hair and a fine aquiline nose, his pleasant facial features belied his ability to conceive cunning solutions to complex problems, and a willingness to selflessly risk his own life in pursuit of them. He was among the last of the small group which had been with young Caesar at Apollonia when news had reached him of his great uncle’s murder.33 Since then Caesar had come to trust him absolutely and he now ranked foremost among his generals. A man of almost the same age, Agrippa’s humble – likely plebeian – background was well known and despised by the Roman aristocracy of old patrician families; in large part it was because he was a novus homo, a man lacking the prestige of coming from a family from which a member had served as a consul.34 Yet in the previous decade, over several campaigns in different theatres of war, he had displayed a flair for battle. Indeed, to the chagrin of many senators, Agrippa had demonstrated many of the qualities the same supercilious aristocrats championed in a war hero and aspired to publicly display themselves. Practicality, preparation, persistence and unpretentiousness were the hallmarks of his leadership style.35 By now he was a battlehardened commander with a formidable reputation. He had quelled a rebellion in Aquitania and was only the second man since Iulius Caesar to cross the Rhine River with troops, for which actions he was granted a triumph (the highest military honour the Roman Commonwealth could grant a citizen) yet declined to celebrate it in deference to his friend, who was enjoying less success in his own campaign against Sex. Pompeius.36 Crucially for the coming war against Antonius (fig. 1), Agrippa had proved he could defeat an opponent at sea. Five years earlier he had led Imp. Caesar’s fleet to victory in two battles off the coast of Sicily against the same Pompeius whose piratical attacks on shipping carrying the grain that fed Rome’s poor had posed an existential threat to Caesar’s precarious political position. His definitive victories there had won him a unique award of a naval crown, specially created for him by his grateful friend.37 All the more remarkably, Agrippa had taught himself the art of fighting on water and beaten a resourceful and much more experienced practitioner of it. Caesar now gambled his entire future upon the abundant talents of Agrippa.

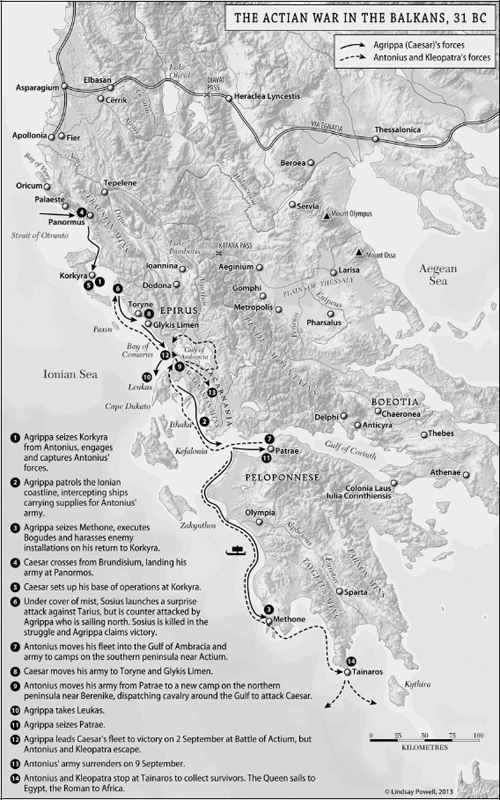

Like Caesar, Agrippa was a thinker and a planner. In the closing months of 32 BCE he had reviewed the military situation to formulate his military strategy. Intelligence reports revealed that Antonius had established garrisons in many towns and shore forts along the coast of Greece, as far east as Colonia Laus Iulia Corinthiensis (modern Corinth), and that he had moved at least part of his fleet and land army to Kerkyra (Corfu), the westernmost Greek island (map 2).38 The deployment could be interpreted as defensive, but more likely it suggested that Antonius intended an amphibious invasion of Italy. With Antonius representing a threat to the security of the homeland, Agrippa wasted no time and immediately dispatched a small flotilla across the Adriatic Sea to block him. Any element of surprise was lost when Antonius’ scouts situated off the Caraunian Mountains spied Agrippa’s ships coming. That might have been his chance to knock Agrippa out of the war, but Antonius then made a serious tactical blunder. Believing these vessels were the vanguard of Caesar’s main fleet, he advanced no further and withdrew to set up his winter quarters at Patrae (modern Patras).39 Agrippa immediately grasped the island from the clutches of the triumvir. The windfall gain of Kerkyra gave Imp. Caesar’s force a vital forward base from which to launch operations along the Greek coast. Agrippa wasted no time and ‘pursued and routed the fugitives in a naval battle, and finally, after accomplishing many acts of the utmost cruelty, came back to Caesar’.40

Figure 1. Triumvir M. Antonius paid his troops with silver coins struck at a military mint. This specimen calls out Legio V. The sleek warship, powered by oars, is shown with mast down and sail furled.

Map 2. The Actian War, 31 BCE.

In the spring of 31 BCE Antonius moved his fleet again, this time into the relatively shallow waters of the Gulf of Ambracia. He established a camp to control access to it on the southern peninsula near a small hamlet called Aktio; it is better known by its Latin name Actium.41 Measuring 40km (25 miles) long and 15km (9 miles) wide, Antonius’ first impressions of the Gulf of Ambracia must have been that it was a safe harbour for his and Kleopatra’s combined fleet. In the meantime, Agrippa was not a man to sit idle. Over the months following that initial encounter at Kerkyra he had led patrols, scoured the Ionian Sea for the transports moving slowly under the weight of foodstuffs and munitions destined for Antonius’ forces, and captured many of them.42 To further weaken the renegade triumvir’s position, Agrippa landed an army at Methone (modern Methoni), a coastal town with stout defences located on the southwestern-most tip of the Peloponnese, which was a first port of call for ships arriving from Asia, Egypt and Syria. Antonius’ ally, Bogudes, king of Mauretania, was in charge of the stronghold. Agrippa besieged it. The town soon fell and Bogudes was captured and executed.43 Heading north again, Agrippa’s attack fleet hunted for enemy vessels and bases on the Greek mainland, constantly degrading his opponent’s resources and causing Antonius no little concern.44 Commanding a group of Antonius’ ships was Sosius, a man with previous experience of war fighting who knew what he was doing. In a fog-enshrouded dawn skirmish, he ambushed Caesar’s ships commanded by L. Tarius Rufus, but failed to capture him. Then, by chance, returning from Methone, Agrippa intercepted Sosius and engaged him in a fight, but Antonius’ man yet again evaded capture.45

In Italy, Imp. Caesar was greatly encouraged by the reports he received of Agrippa’s successful hunter strategy. Leaving Rome in the care of his trusted political advisor C. Cilnius Maecenas, he relocated to the city of Brundisium, which was a vital seaport for travellers to the East. There he addressed many of his supporters, impressing on them that he had the largest and most loyal constituency among the Roman people sympathetic to his cause.46 By March or April of 31 BCE, the main body of his army and navy was assembled at Brundisium, while other units were at Tarentum. Caesar led his force across the Adriatic Sea, unopposed, to the island of Kerkyra. Finding the main city of Corcyra abandoned, he occupied it, anchoring his ships in the adjacent Fresh Water Harbour. From here Actium was just 150km (93 miles) to the southeast. He intended to sail directly to Actium, but a storm blew up, preventing him from landing there.47 When calm seas returned, Caesar finally gave the order for his main force to cross to the Gulf of Ambracia. He hoped to capture Antonius’ fleet undamaged.48

Antonius had now been at Actium for weeks. After an initial survey, he had taken what seemed the prime position on the southern promontory and established his army camp close to the hamlet, which was also a place sacred to the god Apollo.49 The longer he remained there, the more apparent it became to him that his choice of location was a liability; as much as protecting his fleet, the shape of the bay also worked to trap his ships inside.50 Its narrow opening to the Ionian Sea – a mere 700-metre wide channel between Actium on the south and Berenike (modern Berenikea) on the north – formed a bottleneck which Caesar’s fleet could blockade at will. The southern promontory projected northwards into the channel formed by the curve of the opposite shore. In the meantime, his troops had erected watchtowers on each side of the spur of land at the entrances of the channel and stationed ships in between to patrol it.51 Antonius may have planned for the battle with Caesar to take place earlier in the year, but it was not to be.

Antonius had installed his men ‘on the farther side of the narrows, beside the sanctuary [of Apollo], in a level and broad space’, but as a long-term base of operations the site:

was more suitable as a place for fighting than for encamping; it was because of this fact more than any other that they suffered severely from disease, not only during the winter, but much more during the summer.52

Malaria and dysentery are suspected of spreading misery among his troops. Agrippa’s ongoing attacks on Antonius’ supply ships succeeded in denying Antonius’ men much-needed fresh provisions. The morale of the ordinary soldiers, which had been high at the beginning of the year, was sapped by the rising heat and worsening living conditions.53 Flies constantly irritated the men, buzzing around their eyes and lips, congregating when they relieved themselves in the makeshift latrines, then landing on their food as they ate. Logistics could yet make or break Antonius. As long as he held on to the Gulf of Corinth, grain and other supplies brought from the parts of Greece still loyal to him could sustain his troops and keep them loyal.54 As a precaution, he also required his allies and client kingdoms in the East to provide equipment for his campaign.55

In May or June, Caesar finally landed his troops on the shores of Epirus ‘and took up a position on high ground there from which there is a view over all the outer sea around the Paxos islands and over the inner – Ambracian – gulf, as well as over the intervening waters’.56 By design or good fortune, it was an excellent location: his men enjoyed clean water from the nearby springs and Louros River and a continuous supply of fresh provisions could land from Italy; in contrast to Antonius’ men Caesar’s were in good health and high spirits – and likely to remain so.57 Caesar quickly established a defensible position, constructing entrenchments down to the outer harbour called Comarus (Komaros).58 From there the ships could assemble on the Ionian Sea to blockade the enemy fleet. There is an apocryphal story that ships were also active on the other side in the Gulf. Writing some two centuries after the battle, Dio recounts that it was said Caesar had ordered many of his triremes (three-banked warships) dragged over land:

using newly flayed hides smeared with olive oil instead of runways, yet I am unable to name any exploit of these ships inside the Gulf and therefore cannot believe the tradition; for it certainly would have been no small task to draw triremes over so narrow and uneven a tract of land on hides. Nevertheless, this feat is said to have been accomplished in the manner described.59

The Bellum Actiense (Actian Campaign), as it would come to be known, would comprise both land and sea operations. While Agrippa took personal charge of the fleet, he needed a trusted deputy to lead the army. He chose T. Statilius Taurus. He was a man five or six years his senior and, like himself, a novus homo. They had served as consuls together in 37 BCE – Agrippa’s first – and developed a good, robust working relationship. Taurus was a showier personality than his superior, but he was as dedicated to fulfilling his mission and just as courageous. In 36 BCE he had seen action in the war against Sex. Pompeius, commanding a fleet of ships on loan from Antonius off the coast of Africa, for which he likely received an acclamation from his soldiers as imperator – one of three he would receive during his lifetime. His was no small challenge. The men under his direct command at Actium – some 80,000 infantry and 12,000 cavalry – would face Antonius’ numerically superior force of 120,000 foot soldiers and 12,000 mounted troops led by P. Canidius Crassus.60 His opponent was a battle-tested commander, wielding great influence over Antonius. Canidius had served under Lepidus in the Gallic War in the 50s BCE and taken leadership roles under Antonius in wars in Armenia and, most recently, Parthia.61 He boasted that he had no fear of death.62 That claim would be tested.

The tactical details of the campaign still had to be worked out. Agrippa joined Caesar at his praetorium tent in the hilltop camp and, together, they worked on the battle plan. This was their first real opportunity to deal Antonius a knockout blow. Antonius soon realised this too. In an effort to tip the odds in his favour, he moved some of his troops across the strait and set up a second camp directly facing his opponent, and then ordered his cavalry to ride around the Gulf to attack Caesar from the east.63 While Caesar’s men laboured on their ditches, palisades and watchtowers, Antonius’ troops attacked. The target of highest value was Caesar’s supply of fresh water. An army without fresh drinking water could soon be broken. Plutarch reports that Caesar showed great skill in enclosing his sources of potable water behind secure barriers to deprive the enemy of it, since there were so few places around to find it and the water from what ones there were tasted bad.64 He responded by dispatching troops to Achaea and Macedonia to draw Antonius away.65 Taurus showed initiative and daring too when he made a sudden charge on Antonius’ cavalry, defeated it, and also won over Philadelphus, king of Paphlagonia, and his soldiers to Caesar’s side.66

The weakness of Antonius’ stratagem was revealed. His troops were now split on both sides of the Gulf and weakened by it. Exploiting the division of the enemy’s forces, Agrippa made ‘a sudden dash with his fleet’.67 At the same time, Antonius’ navy was effectively trapped in the Gulf of Ambracia while Agrippa’s ships were free to traverse the adjacent Gulf of Corinth at will and patrol the coast of the Peloponnese, where they continued to harass their adversary’s men and sank his warships and grain transports. Many of the targets were of high strategic value, which Antonius could ill afford to lose. ‘Finally, right before the eyes of Antonius and his fleet,’ writes Velleius Paterculus, Agrippa scored a series of tactically important blows: he ‘had stormed Leucas (Levkas)’, capturing a number of enemy ships; ‘had taken Patrae’, Antonius’ winter quarters, by beating Q. Nasidius in a sea-fight; ‘seized Corinth’, Antonius’ provisioning centre; ‘and before the final conflict had twice defeated the fleet of the enemy’.68 Laying due south of Actium, the island of Levkas was a significant win for Agrippa. Stationing warships there and in the Bay of Gomaros to the north, he could establish a blockade or launch an attack on any ships of Antonius’ fleet attempting to enter or leave the strait.

While engagements occurred at sea, Imp. Caesar tried to provoke Antonius to fight on land. According to Dio’s account, he would not oblige him:

Caesar constantly drew up his infantry in battle order in front of the enemy’s camp, often sailed against them with his ships and carried off their transports, with the object of joining battle with only such as were then present, before Antonius’ entire command should assemble. For this very reason the latter was unwilling to stake his all on the cast, and he had recourse for select days to feeling out his enemy and to skirmish until he had gathered his legions.69

This may not be the whole truth. The later report of Orosius presents a different picture in which ‘Antonius decided to hasten the beginning of the battle’, but ‘after quickly drawing up his troops, he advanced toward Caesar’s camp but suffered defeat’.70 Three days later, having failed to make any significant impact on his opponent, Antonius abandoned his second camp on the Epirot side of the Gulf and withdrew under the cover of darkness to his main base near Actium.71

In the wake of this tactical setback, Antonius called a council of war: he urgently needed a new plan. In his headquarters tent the Egyptian queen seemed more of a hindrance than a help. According to Dio, Kleopatra – who was allegedly unsettled by bad auguries – had convinced him that they should entrust the strategic positions to garrisons and let the main force depart to Egypt with herself and Antonius.72 Her subliminal fears seemed to affect Antonius, who began to suspect members of his leadership team of plotting against him. He summarily tortured many and executed several, among them Iamblichus, king of a tribe of the Arabians, and handed over senator Q. Postumius to be torn apart.73 In the last weeks of August, Antonius suffered several high-profile defections. They included the client Galatian kings Amyntas, who had been sent into Macedonia and Thrace to recruit mercenaries, and Deiotaros II (Deiotarus); and the Romans Q. Dellius, who had served him in his war against Parthia, and Domitius Ahenobarbus, the proud ex-consul, allegedly smarting from unrelenting verbal abuse hurled at him by the queen.74 Though deeply upset by Ahenobarbus’ betrayal, Antonius respected the man enough to arrange for his personal effects and slaves to be sent over in another boat.75

The adversaries had been playing a high-stakes waiting game for several months. ‘The two leaders neither were dismayed nor relaxed their preparations for war,’ writes Dio, ‘but spent the winter in spying upon and annoying each other.’76 This stalemate served neither side’s interests and could not last indefinitely. Either they must fight or they must withdraw. According to Dio’s account, Caesar’s plan was to allow his adversaries to sail out of the strait, then chase after them with his swifter fleet and capture Antonius and Kleopatra with as little bloodshed as possible.77 They would make fine trophies in the victory parade he envisaged himself celebrating in Rome – and he needed their treasure.78 The level-headed Agrippa expressed his fear that their opponents would get away and be able to regroup and fight another day; accepting the advice of his close friend, Caesar withdrew his plan.79

Imp. Caesar would certainly have interrogated the defectors from Antonius to better understand his adversary’s intentions. The mission objectives of Antonius and Kleopatra are hard to determine from the extant accounts. They have been passionately debated by historians, ancient and modern, for years. Some – mostly the ancient writers and historians writing before the nineteenth century – are convinced that he was determined to win this battle just as he would any other he had fought in during his career, putting his faith in his heavy warships and loyal troops.80 Others – mostly twentieth-century historians – are willing to dismiss the ancient historians and, instead, believe that his goal was to withdraw from the confines of the Gulf of Ambracia with as many ships and men as possible, taking as much treasure as could be carried, and to hold a last stand somewhere else.81 Another, hybrid interpretation advances Antonius as approaching the mission pragmatically: fighting for victory as the primary, but difficult to achieve objective, with a break-out in force as the more likely achievable outcome.82 The ancient historians all agree on one thing: the disagreement in Antonius’ war council. Dio describes a debate about whether to stay and fight or to withdraw. Kleopatra won with the argument proposing that she and Antonius should escape to Egypt, leaving the troops behind to continue the fight.83 Plutarch reports that Canidius pleaded with Antonius for Kleopatra to be asked to leave so that his commander could fight a decisive battle on dry land (perhaps in Macedonia or Thrace); but the queen argued for a sea battle, implying that her secret motive was to slip away under sail when the opportunity arose, and her paramour agreed.84 In fact the treasure had already been loaded aboard the Egyptian vessels, with sails stowed in the event they could make a dash for open sea. We will probably never know with certainty what Antonius’ plan was on the eve of battle, but it is clear that he would be the one to pick the day and time.

On 29 August, a deep depression settled over the Ionian Sea and adjacent Gulf of Ambracia, bringing with it a severe storm.85 Rain cascaded over the entrance augustus at war - Press flaps of the commanders’ goatskin tents, confining the frustrated leaders inside. Strong winds and choppy waves tossed around the ships of both sides, damaging many, though it appears Agrippa’s ships anchored off Gomaros Bay fared better than Antonius’. The storm continued into a second day, then a third and a fourth. When the commanders awoke on the fifth day, they found, instead, a gentle breeze and a calm sea. ‘Then came the day of the great conflict,’ writes Paterculus, ‘on which Caesar and Antonius led out their fleets and fought, the one for the safety, the other for the ruin, of the world.’86 It was 2 September 31 BCE, a date that would be memorialized as pivotal in the history of the Roman Empire.87

The precise number of ships in the opposing navies continues to provoke argument amongst modern scholars. This is because the ancient sources themselves do not agree. Plutarch reports that Agrippa had 250 ships.88 Orosius details 230 ‘beaked ships’ – referring to the cast bronze rams (rostra) affixed to the prow at sea level – plus thirty ‘without beaks’ and some triremes comparable with the swift Liburnian type of vessel, which Imp. Caesar had brought over with him from Italy (but he excludes from this tally the advance force of Agrippa).89 Florus states that he had 400 ships.90 He explains:

Caesar’s ships had from two (biremes) to six (hexeres) banks of oars and no more; being, therefore, easily handled for any manoeuvre that might be required, whether for attacking, backing water or tacking.91

The design of these ships was similar to those used so effectively by Sex. Pompeius in Sicily to harass the coast of Italy.92 Agrippa had been deeply impressed by the tactical fighting skills of the renegade son of Pompeius Magnus. Learning from his victories at Mylae and Naulochus five years earlier, he had revised his strategy for naval warfare and replaced the equipment with the smaller, but more agile and swifter vessels for the anticipated conflict with Antonius.93 When not ramming and sinking enemy ships, these were platforms delivering marines who would clamber aboard the disabled vessel to fight as they would on land. According to Orosius, the decks ferried the men of eight legions, not counting the five Praetorian Cohorts – a number which is substantially more than the 20,000 heavily armed men plus 2,000 archers in Plutarch’s account.94 Smaller boats carried Caesar’s friends relaying messages between the ships while in action.

The ancient sources are even more divided on the number of ships in Antonius’ fleet than they are of Caesar’s. According to Plutarch, Antonius brought 500 ships with him to Actium.95 Florus states that in battle he had ‘less than 200 warships’, but Orosius gives the precise number as 170.96 The differences in the counts might be explained by the fact that Antonius was forced to burn a number of the Egyptian ships because their crews had died from disease or left through desertion, and he did not want them falling into enemy hands, saving just sixty of the best (being a mix of triremes and dekeres, and not all of his ships were harboured in the Gulf of Ambracia).97 Additionally, some ships had been lost – perhaps to Agrippa’s patrols – and the recent storm had sunk several more.98

Unlike Agrippa, Antonius had no expertise in naval warfare. His fleet comprised large, heavy, multi-banked fighting platforms, among some of the biggest sailing craft of the ancient world. They included ‘many vessels of eight (okteres) and ten (dekeres) banks of oars’.99 Ironically, it seems his choice of vessel was based on studying Agrippa’s victories over Sex. Pompeius where he had deployed enormous warships and large numbers of marines aboard them.100 Antonius had apparently failed to understand that the key difference between the victor and vanquished in 36 BCE was not so much the size of the hardware as the innovative use of the war machines with which Agrippa had equipped them, combined with the talent of its admiral and the quality of the troops.101 Florus confirms the larger size of Antonius’ ships, adding that:

their size compensated for their numerical inferiority [to Agrippa’s]. For having from six to nine (enneres) banks of oars and also rising high out of the water with towers and platforms so as to resemble castles or cities, they made the sea groan and the wind labour as they moved along. Their very size, indeed, was fatal to them.102

The decks were packed with troops, and to enable his soldiers to ‘fight from walls, as it were’ he equipped these floating fortresses with ‘lofty towers’.103 Antonius ordered the masts and sails to be taken aboard the ships, not left on land – against the urgings of his captains – telling them ‘that not one fugitive of the enemy should be allowed to make his escape’.104

The actual number of ships Antonius was able put to sea on 2 September may not, therefore, have been significantly different from Agrippa’s – perhaps as few as 170 vessels, but probably not more than 230.105 The composition of the fleets and warships of the opposing sides differed greatly, however, Agrippa having invested in smaller, lighter and more agile craft, Antonius in substantially bigger, but heavier and slower vessels.

The day of the great battle began well before dawn for Agrippa and Caesar. Agrippa had formed the fleet in the Ionian Sea into a line directly facing the strait of the Gulf of Ambracia at a distance, Dio says, around eight furlongs – approximately a mile – from the enemy.106 Agrippa had taken up a position on the left wing with L. Arruntius.107 Once sympathetic to the assassins of the late dictator (who after the signing of the Treaty of Misenum had switched his allegiance to Imp. Caesar’s caucus), Arruntius was considered an illustrious man, but not much is known about his skills as a combat leader.108 Having exchanged some final words with his admiral, Caesar moved down the line of warships on a small boat, encouraging his soldiers and sailors as he passed them.109 Caesar boarded his own flagship on the right wing of the line with his legatus M. Lurius.110 A native of the Balkans, Lurius was the former proconsul of Sardinia who had showed his mettle in the war against Sex. Pompeius. Agrippa was counting on him to do so again.111 All that was now left to do was to wait for Antonius to make his move.

The hours passed by agonisingly slowly, forcing Agrippa’s men to expend energy by using their oars to hold their ships steady in position.112 But Antonius was preparing for battle. His fleet was forming up in front of the strait, riding up and down with the gentle waves.113 From a row-boat he too was haranguing his soldiers, exhorting them to fight as though they were on land, while ordering his captains to hold their ships at the mouth of the strait and take the blows from the oncoming enemy vessels. There was a surreal, even festive, air to the proceedings. Antonius had decorated his warships ‘in pompous and festal fashion’ while he himself had donned ‘a purple robe studded with large gemstones, a curved scimitar hung at his side and in his hand he gripped a golden sceptre’.114 The soldier had turned showman, intent on making a spectacle of himself.

Like his more modest opponent, Antonius had also sub-divided the command of his fleet. Many were former allies of the men who had struck down Iulius Caesar or had joined the renegade Sex. Pompeius. In charge of the right wing was L. Gellius Publicola, a colourful character who had supported the assassins immediately after the Ides of March before himself entering into nefarious plots to kill the principal conspirators; he narrowly managed to escape with his life, finally defecting to the triumvirs and being rewarded for it with the consulship of 36 BCE.115 The ships in the centre were jointly commanded by M. Insteius, who had accompanied Antonius on his campaigns against the Dardani nation (39–38 BCE), and M. Octavius, a distant cousin to Imp. Caesar, but sympathetic to the assassins, had seen action against his living relation in Illyricum (35–34 BCE) and was one of the few on the team who actually had some experience of commanding a navy.116 Behind them were massed the ships of the Egyptian fleet led by Kleopatra aboard the Antonius, her ‘golden vessel with purple sails’.117 On Antonius’ left wing was C. Sosius, the consul of 32, the outspoken critic of Imp. Caesar and a man with a grudge.118 The ships of the line were arranged in close formation, with little margin for error.119

Having waited for several months in increasingly desperate conditions, Antonius’ men were restless for battle.120 When he judged the moment to be right, Antonius relayed by trumpet to order Sosius to advance against Imp. Caesar and M. Lurius.121 As the oarsmen strained, the massive ships slowly cut a path through the water. Informed of the movement, Agrippa gave the pre-agreed signal for his entire line to row in reverse, taking it further out into the Ionian Sea.122 His fleet now formed a wide concave arc. As far as can be ascertained from the sources, Agrippa’s strategy seems to have been to draw Antonius out from the Gulf and only after he was on open sea to bring his left and right wings forward to encircle him in a naval equivalent of Hannibal Barca’s brilliantly successful manoeuvre at Cannae.123 However, Antonius appears to have anticipated this was exactly what his adversary was planning to do. Advancing his left wing first, he may have intended to break the integrity of his enemy’s single line, hoping to wreak havoc with his bigger fighting platforms.124

The morning had already passed when, between the fifth and sixth hours – approximately 11.56am–12.56pm – a wind began to rise from the northwest from the Ionian Sea.125 It still to this day starts to blow down from the west daily around 11.30am.126 The poet Vergil calls it the Iapyx; it builds in strength through noon, changing direction to west-northwest, becoming a force 3–4 sailing breeze, causing the waves to become agitated between 2.00pm and 3.00pm, before dying out after sunset.127 Agrippa was counting on it to arrive on time. This wind would propel Agrippa’s small ships forward – and work against his opponent’s. Now with the wind against them, Antonius’ galleys moved, propelled by banks of oars – slowly at first, but steadily gaining speed – towards his enemy’s centre.

According to Orosius, battle was joined during the sixth and seventh hours – approximately 12.56pm–1.56pm.128 The ensuing clash is described by Plutarch:

Though the struggle was beginning to be at close range, the ships did not ram or crush one another at all, since Antonius’, owing to their weight, had no impetus, which chiefly gives effect to the blows of the beaks, while Caesar’s not only avoided dashing front to front against rough and hard bronze armour, but did not even venture to ram the enemy’s ships in the side. For their beaks would easily have been broken off by impact against vessels constructed of huge square timbers fastened together with iron. The struggle was therefore like a land battle; or, to speak more truly, like the storming of a walled town. For three or four of Caesar’s vessels were engaged at the same time about one of Antonius’, and the crews fought with wicker shields and spears and punting-poles and fiery missiles; the soldiers of Antonius also shot with catapults from wooden towers.129

Agrippa intended his warships to move at speed to ram and sink his opponent’s; in contrast, Antonius planned to use the higher elevation of his vessels to shoot long-range missiles and cast-iron grapnels to pick off crews and seize his adversary’s ships.130 ‘On the one side,’ writes Dio:

the pilots and the rowers endured the most hardship and fatigue, and on the other side the marines; and the one side resembled cavalry, now making a charge and now retreating, since it was in their power to attack and back off at will, and the others were like heavy-armed troops guarding against the approach of foes and trying their best to hold them.131

After the initial impact, it was not clear who had the advantage.132 Locked in a bloody embrace in the centre, each captain manoeuvered his ship to strike the knockout blow. Agrippa gave the order for his left and right wings to move forward. Made aware of this move on his right side, Publicola slipped off some of the ships from his main formation to avoid being encircled and prepared to engage Agrippa head-on. The unintended result was a split in the centre bloc, creating a gap in the battle line.133 While Arruntius’ vessels collided with those of M. Octavius and M. Insteius, behind them the captains of sixty of the Egyptian ships now ordered their crews to hoist their sails and, as the wind picked up, they plunged through the opening in the line.134 The crews of both Agrippa’s and Antonius’ ships watched the colourful ships sailing through in astonishment. Antonius interpreted the move to mean his queen was leaving the battle and, perhaps in a panic, he followed her aboard a quinquereme.135 The Iapyx was now blowing at full strength. Agrippa’s ships responded to block the way and the rest of Antonius’ fleet found itself trapped. When Antonius’ boat was close enough to Kleopatra’s flagship, he clambered aboard and made straight for the prow.136 Capturing the Antonius and its important cargo would be a major prize for augustus at war - Press Caesar. Before the battle, Agrippa likely gave an order for Antonius’ and Kleopatra’s ships to be taken because ‘at this point, Liburnian ships were seen pursuing them from Caesar’s fleet, but Antonius ordered the ship’s prow turned about to face them, and so kept them off’.137 All his admiral could do now was trust that his officers would carry out their pre-assigned orders.138

Having broken free of Agrippa’s line, the Egyptian ships veered hard southeast. With the wind filling their sails, they slipped away at speed, taking the Roman commander, queen and treasure with them. The effect on Antonius’ men who were left behind was devastating. Had Antonius abandoned them? Some crews sought to follow after their commander, throwing overboard anything to lighten their weight, but they were unable to keep up.139 Agrippa, however, held his nerve; tempting as it was to go in pursuit, he was not about to let his opponent’s main fleet get away. The battle raged with increasing violence:

For Caesar’s men damaged the lower parts of the ships all around, crushed the oars, snapped off the rudders, and climbing on the decks, seized hold of some of the foe and pulled them down, pushed off others, and fought with yet others, since they were now equal to them in numbers; and Antonius’ men pushed their assailants back with boathooks, cut them down with axes, hurled down upon them stones and heavy missiles made ready for just this purpose, drove back those who tried to climb up, and fought with those who came within reach. An eye-witness of what took place might have compared it, likening small things to great, to walled towns or else islands, many in number and close together, being besieged from the sea. Thus the one party strove to scale the boats as they would the dry land or a fortress, and eagerly brought to bear all the implements that have to do with such an operation, and the others tried to repel them, devising every means that is commonly used in such a case.140

Agrippa’s and Caesar’s flagships were now just two vessel amongst many in the general mêlée upon the Ionian Sea (plate 6). The captains of their fleet ‘scattered at their will the opposing vessels, which were clumsy and in every respect unwieldy, several of them attacking a single ship with missiles and with their beaks, and also with firebrands hurled into them’.141 Hoping to capture Antonius’ ships undamaged, and the men aboard them, Caesar wanted to avoid using firebrands, even calling out to Antonius’ troops to lay down their arms now that their commander had fled, but that was now an unattainable goal.142 ‘Now another kind of battle was entered upon,’ writes Dio:

where the assailants would approach their victims from many directions at once, shoot blazing missiles at them, hurl with their hands torches fastened to javelins and with the aid of engines would throw from a distance pots full of charcoal and pitch. The defenders tried to ward these missiles off one by one, and when some of them got past them and caught the timbers and at once started a great fire, as must be the case in a ship, they used first the drinking water which they carried on board and extinguished some of the conflagrations, and when that was gone they dipped up the sea-water. And if they used great quantities of it at once, they would somehow stop the fire by main force; but they were unable to do this everywhere, for the buckets they had were not numerous nor large size, and in their confusion they brought them up half full, so that, far from helping the situation at all, they only increased the flames, since salt water poured on a fire in small quantities makes it burn vigorously. So when they found themselves getting the worst of it in this respect also, they heaped on the blaze their thick mantles and the corpses, and for a time these checked the fire and it seemed to abate; but later, especially when the wind raged furiously, the flames flared up more than ever, fed by this very fuel. So long as only a part of the ship was on fire, men would stand by that part and leap into it, hewing away or scattering the timbers; and these detached timbers were hurled by some into the sea and by others against their opponents, in the hope that they, too, might possibly be injured by these missiles. Others would go to the still sound portion of their ship and now more than ever would make use of their grappling-irons and their long spears with the purpose of binding some hostile ship to theirs and crossing over to it, if possible, or, if not, of setting it on fire likewise.143

Wherever fires raged, men suffered terribly from inhaling choking smoke or, becoming engulfed in flames, suffered terrible burns or, having leaped overboard to save themselves, sank under the weight of their sodden clothing or armour and drowned.144

The battle raged on through early evening according to Orosius’ account.145 ‘The contest continued to so late an hour,’ writes Suetonius, ‘that the victor passed the night on board.’146 Florus is more precise: only after Antonius’ fleet was ‘most severely damaged by the high sea’ did his men finally give up the fight at the tenth hour – around 4.16pm.147 At daybreak next morning, Caesar felt able to declare victory his.148 Some would reckon the years of his reign from this moment.149 As the sun rose on the morning of 3 September, the survivors could survey the gruesome carnage of the previous day’s battle. It is graphically – if poetically – evoked by Florus, who writes:

The vastness of the enemy’s forces was never more apparent than after the victory; for, as a result of the battle, the wreckage of the huge fleet floated all over the sea, and the waves, stirred by the winds, continually yielded up the purple and gold-bespangled spoils of the Arabians and Sabaeans and a thousand other Asiatic peoples.150

Agrippa had successfully completed his mission and won the battle for Caesar. By one account he had captured 300 of his enemy’s ships, which is likely an exaggeration.151 Yet victory had come at a heavy price. The casualties on Caesar’s side were 12,000 dead and 6,000 wounded – and of them 1,000 died later despite receiving medical care; of Antonius’ men, some 5,000 had lost their lives.152 On land, Antonius’ nineteen legions of men-at-arms standing undefeated in battle, and 12,000 cavalry, could not accept that their commander had simply abandoned them. As late as seven days after the Battle of Actium, they still believed that he would make a surprise deus ex machina-style appearance and lead them to victory.153 Only when Canidius Crassus was found – despite his boast – to have proved a coward and deserted them (he had sneaked away under the cover of darkness) did the men finally capitulate and offer their unconditional surrender to Imp. Caesar.154 When captured, Canidius was summarily executed.155 Ex-consul Sosius fled the region and went into hiding, but he too was soon discovered and taken captive.156 When Arruntius, a man well-known for his old-time dignity, advocated on the prisoner’s behalf for his life, Imp. Caesar showed clemency (clementia) and pardoned him.157 But Caesar needed to make examples of some and there were other retributions. The client kings who had aligned with Antonius were punished by confiscations of their lands and titles; cities saw their privileges withdrawn; Roman senators and equites were either fined, exiled or executed.158 On the fates of Antonius’ other legates (L. Gellius Publicola, M. Insteius and M. Octavius), history is silent: they may have died in the battle.

If the Actian campaign had been won, while the antagonists were still on the run the larger war against Antonius and Kleopatra had not. Capturing the fugitives now became the regime’s top priority. Agrippa dispatched part of his fleet in pursuit of them.159 For the time being the defeated triumvir and the queen had managed to evade the pursuers, who finally gave up the chase and returned to the security of Comarus harbour. Any last remaining pockets of resistance had also to be flushed out: Caesar could not afford a repeat of the type of insurgency led by Sex. Pompeius five years earlier.160 Remnants of Antonius’ army were retreating to Macedonia, where they might regroup and stage a last stand. Agrippa intercepted them and, to everyone’s relief, received their surrender without bloodshed. He took the enemy’s fortified coastal locations, encountering no opposition in the process. Crucially, he secured for his commander-in-chief Colonia Laus Iulia Corinthiensis, which Iulius Caesar had refounded as a colony of army veterans just months before his assassination; it had been the only Greek city to shut its gates to his official heir.161

Imp. Caesar wanted to return to Italy without delay, but there was much to do locally before he could leave. He decided to stay in Athens for the remainder of the year, conducting affairs of state from there and hoping to discover Antonius’ whereabouts.162 He soon learned how his adversary had abused the free Greek communities.163 To pay for his war effort, Antonius had ravaged them, confiscated their money, slaves and animals; their citizens – among whom was Plutarch’s own uncle, Nikarchos – had even been forced to carry heavy loads of grain upon their backs like slaves to Antikyra and load up the vessels bound for Antonius’ camp at Actium.164

With a clear eye to shaping his legacy, he founded a new city on the site of his army camp and populated it with the inhabitants of smaller settlements in the surrounding region.165 The name he gave to this place was Nikopolis, ‘Victory City’, in honour of his success at Actium. The centrepiece, to be erected upon the highest point above a grove sacred to Apollo (Imp. Caesar’s patron god), was a war memorial adorned with the spoils of the Actian War (plate 8).166 Games dedicated to Apollo Actius were inaugurated, to take place every five years, and ground was broken for a gymnasium and stadium to be built to host the athletic competitions.

When the Antonius sailed away, it took not only Kleopatra but also the treasure Caesar had hoped to use to pay his troops. He had insufficient funds to cover his financial obligations to them from his own resources. His problems were now exacerbated by the fact his ranks were swollen with men from Antonius’ legions: an additional nineteen legions now swore allegiance to him, bringing the total to almost sixty.167 His own men had remained loyal to him through the long, hard years of campaigning, not entirely out of selfless service – though undoubtedly there were men among them who believed in Caesar’s cause – but for the regular pay. They also had hopes to be rewarded with distributions from the rich pickings of Egypt. The seeming lack of activity since the day of the Battle of Actium led many soldiers to question whether this would actually happen at all. Trying to avoid a showdown, Caesar played for time. Statilius Taurus’ officers managed to keep the rank and file in check. Most of the veterans (men who had served sixteen years) faced demobilization anyway, but when they realized they were not going to receive any cash payment or grant of land for their service to help them into retirement, they began to protest.168 With much at stake, Caesar could ill afford a mutiny. Fearing the resentful mood might spread to all the men, he needed someone to repatriate the legions to Italy and resettle the men without delay.169

Caesar required a strong authority figure. Agrippa was an ex-consul who carried high status and was a decorated commander. Crucially, he had imperium (military power based in law). Maecenas, Caesar’s present deputy in Rome, a member of the ordo equester, did not.170 Yet the two men complemented Caesar’s skills and temperament well and formed his personal, but unofficial, council of advisors (consilium). Where Agrippa brought experience and judgment in management and military matters, Maecenas provided the connections and defttouch Caesar needed to get political things done. Caesar empowered both men to speak and act for him in his absence.171 The unglamorous task of transporting the troops to Italy and demobbing them fell to Agrippa. Over the subsequent months of autumn and winter, Agrippa would write frequently to Caesar; he urged him to return to Italy to deal with matters which required his personal presence.172 The fact he was making these direct requests strongly suggests that, despite his status and authorization, he was struggling to deal with the grievances of the veterans and concerned that control of the situation might be lost if Caesar did not return and assert his authority. Even after the conclusive result at Actium, Rome was not a safe place for M. Agrippa. As Caesar’s senior representative, he faced real personal danger. A plot to assassinate Imp. Caesar, led by the son of the former triumvir Aemilius Lepidus, had been exposed this year and quelled by Maecenas.173 Someone with the motive and the means could also attempt to assassinate Caesar’s right-hand man at any moment. With Caesar away, the men growing impatient and the end of the year approaching, Agrippa would have to do the best he could with what he had.

| Imp. Caesar Divi f. IV | M. Licinius M. f. Crassus | |

| suff. | C. Antistius C. f. Vetus | |

| suff. | M. Tullius M. f. Cicero | |

| suff. | L. Saenius L. f. (Balbinus) |

Caesar finally relented to Agrippa’s written pleadings and agreed to return to the homeland.174 He had, in any case, been elected as consul for the year 30 BCE, his fourth term in that high office.175 Before leaving Athens, he delegated to others the important mission of finding Antonius, whose whereabouts were still unknown.176 Caesar was greeted on the quayside at Brundisium by a large delegation. Agrippa, Maecenas, members of the Senate and the equites, along with other high-status people, joined in a public display of support for the victor of the Actian War.177

While ensuring the security of Roman territory and its people continued to be the priority, and even though the war with the treacherous queen and renegade triumvir was not yet over, many army units still needed to be drawn down and redeployed. At Brundisium, after a strategic military review, ‘he assigned different legions to posts throughout the world’.178 Solving the challenge of resettling the troops to be demobbed, however, was uppermost on Caesar’s mind. With him he had brought chests of money with which to settle the outstanding debt of the disaffected veterans; to the men who had loyally served him, he also granted the allotments they were promised.179 He found the plots of land in Italy by confiscating property held by friends and allies of Antonius, but he was careful to compensate those negatively affected with other land in Dyrrhacium, Philippi and elsewhere, promising payment to those unsuccessful in getting alternative accommodations.180 Caesar’s policy decision had unintended consequences. He discovered that he was spending more cash than he had available. To raise funds he announced that he had put up for auction his own property, as well as that of his friends.181 Although no buildings found new owners and no money actually ever changed hands, it demonstrated Caesar’s willingness to go to this length to deal with the matter and it did succeed in buying him valuable time. He might have chosen, at this time, to punish those who had not supported him, but he did not. He issued to those who had received amnesty the right to live in Italy, and to the people who had sworn the sacramentum but failed to come out to greet him in Brundisium he issued a general pardon.182

Caesar urgently needed to find the treasure smuggled away by Kleopatra. Just a month after having landed in Italy, he boarded a ship and sailed again for Greece.183 From there he went first to Asia Minor and then to Syria, settling local affairs as he went.184 In the meantime, Caesar sent Cornelius Gallus to Africa. An eques (a man of the Ordo Equester), Gallus was an educated man – he had the same tutor as the poet Vergil – and he could be trusted to carry out his orders. Almost as soon as he had landed he received the surrender of Antonius’ commander, L. Pinarius Scarpus, and his four legions stationed at Cyrene – all without a fight.185 Now Antonius made a move. On Egypt’s western border with Libya at Paraetonium (modern Mersa Matruh), he intercepted Gallus. After a skirmish, Antonius was defeated, and when he retreated to Pharos, Caesar’s deputy overwhelmed him a second time. 186

In Egypt, Kleopatra was desperately rallying her army in readiness for a last stand. All men of military age were conscripted, including her own son, Caesarion, and Antonius’ son, Antyllus.187 ‘Their purpose,’ writes Dio:

was to arouse the enthusiasm of the Egyptians, who would feel that they had at last a man for their king, and to cause the rest to continue the struggle with these boys as their leaders, in case anything untoward should happen to the parents.188

Meanwhile, she sent out emissaries carrying peace proposals intended to be read by Caesar, and money to bribe his allies.189 To him she sent her golden crown and sceptre, and her throne too: if she was willing to hand him the symbols of her rule, perhaps he would be merciful.190 She did this, however, without first consulting Antonius. Caesar saw an opportunity:

Caesar accepted her gifts as a good omen, but made no answer to Antonius; to Kleopatra, however, although he publicly sent threatening messages, including the announcement that, if she would give up her armed forces and renounce her sovereignty, he would consider what ought to be done in her case, he secretly sent word that, if she would kill Antonius, he would grant her pardon and leave her realm inviolate.191

Secret negotiations between the foes continued.192 Kleopatra promised money. Antonius too appealed to Caesar’s better nature, reminding him of their family ties. One of the surviving murderers of Iulius Caesar who had been living with Antonius was handed over in exchange for sparing the queen’s life, but Imp. Caesar summarily executed him. Antonius sent his son bearing gold, but Caesar returned him – alive but empty-handed and without an answer. Publicly he maintained his posture that Kleopatra should surrender unconditionally: he feared that she might escape and launch an insurgency in another part of the Roman world.193 Privately he appealed to her vanity, sending his freedman Thyrsus with a message that he loved her just as much as the rest of mankind, but that she should leave Antonius and keep her money safe.194

When Caesar took Pelusium on the eastern side of the Nile delta (or the garrison there simply surrendered to him), he had gained an important foothold in Egypt.195 His men and matériel were now just a week’s march away from the Egyptian capital. When Caesar arrived outside the city founded by Alexander III of Macedon, but weary from the journey, Antonius and a unit of cavalry attacked him and prevented him from taking it.196 Loyalties were tested. Valerius Maximus preserves the story of Maevius, a centurion in Imp. Caesar’s army. At Alexandria he was ambushed and taken captive. Presented to Antonius, he was asked what should be done with him? ‘Kill me!’ he replied unflinchingly, ‘because neither the benefit of life nor the sentence of death can stop me from being Caesar’s, or becoming yours.’198 Impressed by his resolution, the renegade commander spared his life.

The first battle of the Alexandrian campaign (Bellum Alexandreae), which Caesar had led, had been fought and lost. Antonius then tried to win over Caesar’s men with a direct appeal. Over the camp’s palisade he shot arrows, attached to which were papyrus pamphlets promising 6,000 sestertii to every man who joined him.199 Caesar turned Antonius’ appeal to his own advantage. He assembled his troops and from a tribunal read out the message himself, and proceeded to belittle the old commander’s attempt to lure away his men.200 They remained loyal.

On 1 August, Alexandria fell to Imp. Caesar. Egypt’s fate was sealed. From that time the date would hold special significance for Caesar:

The day on which Alexandria had been captured they declared a lucky day, and directed that in future years it should be taken by the inhabitants of that city as the starting-point in their reckoning of time. 201

In learning the story of their ‘Year 0’, future generations of Alexandrians would be reminded of the victory of the Roman commander and the folly of the Egyptian queen.

Left without an army, Antonius took refuge in the few ships he had remaining from his navy. He fell into a depression and began to ponder staging a last battle at sea or even escaping to Hispania Ulterior.202 According to Dio’s account, the queen had secretly intervened and caused his sailors to desert him while she withdrew to her mausoleum.203 The broken Roman commander now suspected her of betraying him; nevertheless he suggested he might consider taking his own life if it would mean his wife (the queen) could live.204

The true story of the final hours of Antonius and Kleopatra may never be known with certainty. On 10 August, he died from a self-inflicted wound and it was reported that she died from poison – legend has it from the bite of an asp – though professional assassination is equally plausible.205 Imp. Caesar allowed their bodies to be prepared, embalmed and buried in the queen’s mausoleum.206 He spared the children of Antonius’ marriage to both Fulvia and Kleopatra, except two. Caesarion (allegedly the lovechild of Iulius Caesar and the queen) was captured while trying to flee to India via Ethiopia and was executed; Antyllus, who was betrayed by his tutor, was beheaded.207

The ancient kingdom of the pharaohs had become the property of the younger republic of the Roman People (plate 7).208 Egypt produced one of Rome’s most important strategic resources – grain. Caesar needed a man he could trust to administer it. His most important duty would be to ensure an uninterrupted flow of grain shipped from its warehouses so that the hungry poor of Rome could have their daily bread.209 Caesar placed Cornelius Gallus in charge of the new province as its first Praefectus Aegypti. Gallus had proved loyal in recent weeks, and was available at the time and place Caesar needed him. From that time on the position would always be filled by praefectus, a man of equestrian social rank. As an additional precaution, no men of senatorial rank were allowed entry to the country unless with the explicit permission of Caesar.210 In support of him, two or three legions would be stationed in the province, Legiones III Cyrenaica, XII Fulminata and XXII Deiotariana.

While in Alexandria, Caesar viewed the preserved body of Alexander the Great. Already three centuries old, it had been mellified and lay in a sepulchre preserved in a sarcophagus of glass, alabaster or quartz crystal.211 ‘After gazing on it,’ writes Suetonius, Caesar ‘showed his respect by placing upon it a golden crown and strewing it with flowers; and being then asked whether he wished to see the tomb of the Ptolemies as well, he replied, ‘‘My wish was to see a king, not corpses’’.’212 If the rumour preserved in Dio’s account is true, when Caesar actually touched the body a piece of the nose broke off.213

The war against Antonius and Kleopatra was now officially over. With several legions at his disposal, rather than let the men spend their time in idleness he assigned them to labour-intensive projects to improve Egypt’s infrastructure:

To make it more fruitful and better adapted to supply the city [of Rome] with grain, he set his soldiers at work cleaning out all the canals into which the Nile overflows, which in the course of many years had become choked with mud.214

The victor also requested a lasting monument to be built to mark his achievement. ‘Caesar founded a city there on the very site of the battle,’ records Dio, ‘and gave to it the same name and the same games as to the city he had founded previously.’215 As he had done beside Actium in Epirus, so at Alexandria in Egypt he founded Nikopolis, a second ‘Victory City’. Located a few miles east of the old city, when completed the new one would feature state-of-the art architecture, manicured gardens, precincts, an amphitheatre, a gymnasium and a stadium to host quinquennial games.216 In time it would prove so popular that the old buildings of Alexandria would fall into disrepair.

The last item for which Caesar had waged war was gold. In that regard the former queen had, unwittingly, been most helpful. ‘In the palace quantities of treasure were found,’ writes Dio:

for Kleopatra had taken practically all the offerings from even the holiest shrines and so helped the Romans swell their spoils without incurring any defilement on their own part. Large sums were also obtained from every man against whom any charge of misdemeanour were brought. And apart from these, all the rest, even though no particular complaint could be lodged against them, had two-thirds of their property demanded of them. Out of this wealth all the troops received what was owing them, and those who were with Caesar at the time got in addition 1,000 sestertii on condition of not plundering the city.217

Caesar knew full well that to leave debts unsettled could turn a friend into a foe. Those who had advanced him loans would soon be repaid in full. To both the senators and the equites who had actively participated in the war large sums would also be given as rewards. Rome and its temples too would be adorned from the proceeds of the war spoils (ex manubiis) of Egypt to maintain the goodwill of the gods.218 In Rome the Senate voted him both a triumph and sacrifices.219 In no hurry to return home, Caesar chose to remain in Egypt for the rest of 30 BCE.

The annexation of Egypt brought not only vast natural resources and unfathomable wealth, it greatly added to the size of the Roman Empire. Rome’’s dominions now bounded the largest part of the Iberian Peninsula, Gaul, Italy below the Po River, the western Balkans, all of Greece, parts of Anatolia, Syria, tracts of North Africa and all the islands scattered across the Mediterranean, known to the conceited Romans simply as Mare Nostrum, ‘Our Sea’. Rome’s southernmost limit was now set at the First Cataract on the Nile River. A Roman garrison would soon have to be established in the Dodekashoinos on the border with Ethiopia. Enormous numbers of Roman troops had been withdrawn from the other territories to participate in the contest between the two men fighting to rule the Roman world.220 The few military units still stationed in the provinces continued their regular duties as best they could. Some even excelled. In Gallia Comata, the army of C. Carrinas, a man who had a history of underperformance but whose services Caesar had retained as its governor, scored two great successes. He completed a punitive campaign against the Germanic nation of the Suebi, who had crossed the Rhine River and raided into his province to rampage through its largely unprotected settlements, and also quelled a revolt of the native Morini in Belgica.221 In the Iberian Peninsula, C. Calvisius Sabinus led operations with distinction. In Africa, proconsul L. Autronius Paetus dealt with an unspecified challenge by military force. All three men’s achievements were recognised when the Senate voted them triumphs.222

In northern Greece, the proconsul of Macedonia, M. Licinius Crassus, lived up to the reputation for courage of the greatest of Rome’s military heroes. The grandson of the man who invaded Parthia and lost his life, and the eagle standards of his legions too, may have felt he had something to prove.223 On the northern border of his province lived the Bastarnae and, beyond the Danube River, the Daci.224 The Bastarnae were a people from Scythia (a region that would now be southwestern Russia) who had migrated west and crossed over the river into the territory already occupied by several native tribes, principally the Dardani and Triballi, and collectively called Moesi.225 The Roman perspective was that as long as the Bastarnae did not encroach on Roman territory or attack one of their allies, they would not interfere.226 However, when the Bastarnae crossed the Haemus (an unidentified mountain range in the Balkans) into the region of Thracia ruled by Sitas, the blind king of the Dentheleti, who was an ally, the Romans were obliged to intervene.227 ‘Chiefly out of fear for Macedonia,’ writes Dio, Crassus went out to meet them.228 Extraordinarily, ‘by his mere approach he threw them into a panic and drove them from the country without a battle’.229 Seeing an opportunity, he pursued them as they retreated. He took the region called Segetica and, having invaded the plains south of the Danube, ravaged the country and staged an assault on one of the main strongholds.230 According to Florus:

One of their leaders, after calling for silence, exclaimed in front of the host, ‘Who are you?’ And when the reply was given, ‘We are Romans, lords of the world.’ ‘So you will be,’ was the answer, ‘if you conquer us.’ Marcus Crassus accepted the omen.231

The Moesi repulsed his vanguard, believing it was the entire force, and made a sortie from their fortification. It was a tactical mistake. Crassus brought up reinforcements, pushed back the enemy, then besieged and destroyed the stronghold. The Bastarnae halted their retreat at the Cedrus (Tsibritsa) River.232 Having witnessed what Crassus had done to the Moesi, they sent emissaries to Crassus with a petition for him not to pursue them because they had done the Romans no real harm. Again Crassus saw an opportunity. He received the envoys, telling them he would give them an answer the following day, but in the meantime he treated them to his hospitality and interviewed them as they drank copiously.233 From the inebriated guests the proconsul learned about their true intentions. Forearmed with this intelligence, that night he led an assault against the enemy under cover of darkness:

Crassus moved forward into a forest during the night, stationed scouts in front of it, and halted his army there. Then, when the Bastarnae, in the belief that the scouts were all alone, rushed to attack them and pursued them as they retreated into the thick of the forest, he destroyed many of them on the spot and many others in the rout which followed.234

Their retreat was blocked by waggons and pack animals they had parked at their rear.235 Women and children were trapped between them and, in the general mêlée which followed, were slaughtered.

During the bloody struggle Crassus displayed virtus, the attribute of selfless courage or manliness, which the Romans greatly respected in their leaders. He had personally sought out Deldo, king of the Bastarnae, to engage him in a duel; the two commanders fought and, after a fierce struggle, the Roman slew his royal opponent.236 As was his right, he stripped the armour from the dead war chief and claimed it as spolia opima, ‘rich spoils’. By tradition he could look forward to the honour of taking these and dedicating them in the Temple of Iupiter Feretrius. He would be only the fourth man in history to do so.237 Only two men since the city’s legendary founder Romulus had been deemed worthy: A. Cornelius Cossus in either 437 or 426 BCE, and M. Claudius Marcellus in 222 BCE.238 Virtus was shown by other ranks too:

No little terror was inspired in the barbarians by the centurion Cornidius, a man of rather barbarous stupidity, which, however, was not without effect upon men of similar character; carrying on the top of his helmet a pan of coals which were fanned by the movement of his body, he scattered flame from his head, which had the appearance of being on fire.239

Without their leader, the resistance broke. Some Bastarnae perished when they took refuge in a grove, which the Romans then set on fire; others rushed into a fort, where they were butchered by Crassus’ troops; yet others drowned when they leaped into the Danube, or died of hunger when they were separated from each other and scattered across the country.240 There were survivors, however. They rallied and staged a last stand.241 Crassus besieged them for several days but the defenders inside held out and the frustrated Roman commander reluctantly withdrew. Finally, with the addition of troops of Rolis (Roles), king of the Getae nation, Crassus’ army tried again and this time sacked the stronghold. The captives were distributed as war booty (praeda) among the soldiers for use as slaves.242 For leading them to this victory, his troops may have acclaimed him imperator.243