4

In the Groove

Practices and Practicing to Create an Everyone Culture

In this chapter we show you specific ways individuals in DDOs are continuously engaged in getting over themselves—identifying their weaknesses, seeing deeply into the ways they’re stuck, and having regular opportunities to move past their limiting patterns of thinking and acting. We describe the practices each organization has developed and continues to refine that help everyone become a better version of herself. It may be tempting, therefore, to scan for the practices to import into your own work culture, following them like a recipe.

But we hope you don’t read the chapter in that way.

Instead, we invite you to first consider the idea of practice in terms of the larger context, purpose, and outlook in these DDOs. Understanding a DDO’s approach to practice will give you a much better sense of how to think about bringing practices into (or creating new practices for) your own organization. We refer to all the developmental tools, habits, formalized behaviors, and types of meetings in DDOs as practices, because the word reminds us that we’re doing something in a certain spirit, with a particular intention.

Consider what it means to practice, to have a practice, and to be practicing. Perhaps the central idea is that we’re doing something repeatedly, with the intention of becoming better at it. In other words, when we’re practicing, we are not expecting (and others are not expecting us) to perform perfectly. In naming what we’re doing practice, we signal that we’re experimenting, trying something on, working at improving. And we clarify that practice is what we’re supposed to be doing—trying hard at something to get better at it. We’re creating conditions in which we won’t feel pressure to demonstrate expertise, conditions that will allow us to experiment, that will allow us to gather feedback, that will help us learn.

Practice also suggests we’re doing something routinely, regularly, as a normal part of our lives. We think that the way to get better at something requires us to make learning it part of our routine. We expect to be practicing today, tomorrow, and on into the foreseeable future. Although we’re trying to become proficient, we never reach completion. Our practicing, and therefore our learning, never stops.

When you think about practice in these ways, what type of practice comes to mind? Practicing a sport? A musical instrument? Meditation? It isn’t a coincidence that most people don’t think this way about their jobs. The culture of most organizations is not designed for practice; it’s designed for performance. Everyone is trying to look good, display expertise, minimize and hide any mistakes or weaknesses, and demonstrate what they already know and can do well. In a culture of practice, in contrast, everyone is learning and growing.

Simply copying DDO practices doesn’t work, therefore, because it’s not sufficient to give people time and space and rules for practicing. You must also pay attention to creating a culture of practice, helping people adopt the spirit, intentions, and mind-set of practice, rather than those of performance.

When we talk to people who’ve been immersed in the culture of practice in DDOs for at least a couple of years, they describe the ways their own mind-set began to change from one of performance to one of practice. They tell us how hard it was to receive feedback until they realized that the feedback was being given to help them get better. They describe how hard it was to admit and accept their own weaknesses and realize that the sooner they could see them, the sooner they could learn to improve them. And they explain that the more they could see others accepting feedback, practicing, learning, improving, and growing, the more their own resistance to this type of learning began to dissolve.

Another reason that copying DDO practices will not work is that effective practice depends on many factors. The literature on deliberate practice shows that improvement depends on how frequently we practice tasks that present increasing challenge. Improvement also depends heavily on how we practice. Ideally, practice sessions are designed and supervised by experts who break down our performance to give specific advice about how to practice and who give us feedback about what needs to improve. Perhaps that is one reason all three DDOs are quick to create and try new practices, gathering information about how well they work and help people learn.

Instead of looking for what you can simply copy, we hope you will read about these practices and ask yourself questions like these: Under what conditions could this practice lead to learning and improvement? What type of improvement? For what purpose? How would someone need to practice to begin to see that improvement? We hope that, like all three DDOs we describe, you will want to try things for yourself and experiment with instituting new practices at work as you also step back to gather information, assess the practices, and experiment again.

As we look deeper into the groove of daily life in the three DDO exemplars, we hope you’ll see what distinguishes the practices in each company: that they form a system of routines and tools for exposing, exploring, and transcending people’s limiting assumptions and mind-sets. Each practice plays its own part in the life of the company, but no practice stands on its own. In each of these companies, practicing is constant, immersive, and layered at multiple levels and time scales.

In an everyone culture, these practices make up the important patterns of working life that everyone participates in—as individuals, in small teams, within divisions, and across the company. It’s that saturation of practices that produces a uniquely rich culture for developing people.

Bridgewater: Tools for Getting in Sync

Your earlier visit to Bridgewater’s campus in the woods of suburban Connecticut has given you a sense of the kind of dialogue that happens every day there. In every conference room and corner, people are working to get in sync about what is true. Radical transparency can happen face-to-face, as people strive to apply the principles, exposing their reasoning and performance to continuous scrutiny. A practice unthinkable in most companies—recording and sharing the recording of every meeting (including those with visiting researchers like the authors of this book)—is standard practice here.

What other routines and tools does Bridgewater use to bring this thick culture of radical transparency to life? How does the collection of daily workplace practices create a machine for better business results and increasingly effective employees through the search for truth?

An App for That: Dot Collector

In talking about the idea meritocracy that Bridgewater aspires to be, CEO Greg Jensen describes the need for an ecosystem of practical tools to support the challenging work required.

You build the habits of principled people into the everyday work. So there’s no difference between doing the work and managing the work. It’s all the same stuff . . . And therefore, [we] embed those habits in the technology and the tools, so that the way you are doing things is consistent with those principles. You’re building the habits, and you’re building the muscle memory to operate in a certain way. It’s very hard to teach people to be fully transparent, to be all of those ways, and so you really need to help them by creating the ecosystem that almost forces them to in doing their work.

To see how this interpersonal ecosystem works, let’s power up the standard-issue tablet device. In a key practice for building muscle memory, everyone shares a continuous stream of feedback about people’s behavior using an application called the Dot Collector. This custom tool allows people to record their assessments of any other person in two ways: summary ratings—thumbs-up, thumbs-down—and candid, specific comments about the person’s actions or inaction.

The dots are individual data points, which are aggregated to reveal larger crowd-sourced patterns to connect the dots. Think of it as Big Data meets human development. The accumulated dots create, in Bridgewater’s phrase, “a pointillist picture of a person” over time—one that employees and managers can use, as one of several tools, to generate inferences about what people are like (WAPLs) and identify the developmental work individuals need to do to be more successful in given roles.

Everyone’s getting and giving feedback on how he’s doing in his job. Jensen is not exempt; there are no exemptions. A sampling from a day’s accumulated dots from June 2014 shows the kinds of feedback he gets from across the company, including from his own subordinates, in evaluative categories such as creativity, conceptual thinking, managing vision and purpose, and process management. Some of the live feedback Jensen got that day reflected frank assessments of his leadership:

Let WGOITW meeting (“What’s Going On in the World” meeting, which Jensen is responsible for) devolve into a bit of chaos.

Let WGOITW meeting (“What’s Going On in the World” meeting, which Jensen is responsible for) devolve into a bit of chaos.

Good WGOITW meeting.

Good WGOITW meeting.

Greg, you’re too slow in finding a sustainable design for Nella’s responsibility set.

Greg, you’re too slow in finding a sustainable design for Nella’s responsibility set.

Not prioritizing finding a replacement for Nella.

Not prioritizing finding a replacement for Nella.

The Issues Log

The flow of data about people via the Dot Collector is supplemented by other practices that Bridgewater can use to get at root causes of problems. One tool for perceiving, diagnosing, and preventing problems is the issues log, a digital tool for capturing, from a first-person perspective, questions and evidence about errors, mistakes, and problems. Jensen told us that the issues log “is like our evolution machine” for “watching the progress on any problem that’s ever been raised in the company.”

At Bridgewater, making mistakes is expected—and disclosing and reflecting on the causes of errors are a job requirement. Ray Dalio describes the way big and small problems are diagnosed through the issues log.

A problem or “issue” that should be logged is easy to identify: anything that went wrong. The issues log acts like a water filter that catches garbage. By examining the garbage and determining where it came from, you can determine how to eliminate it at the source . . . The log must include a frank assessment of individual contributions to the problems alongside their strengths and weaknesses. As you come up with the changes that will reduce or eliminate the garbage, the water will become cleaner.

Dalio goes on to explain how people will resist using the issues log if it’s seen only as a way to cast blame on others.

A common challenge to getting people to use issues logs is that they are sometimes viewed as vehicles for blaming people. You have to encourage use by making clear how necessary they are, rewarding active usage, and punishing nonuse. If, for example, something goes wrong and it’s not in the issues log, the relevant people should be in big trouble. But if something goes wrong and it’s there (and, ideally, properly diagnosed), the relevant people will probably be rewarded or praised. But there must be personal accountability.

Let’s take the example of one such entry. Rohit, a junior staffer in the research department, notices that a department is experiencing problems, and he questions how Alex, the department head, is overseeing the work. Here’s a part of Rohit’s issues log entry:

We’ve been struggling to keep up with all of our needs, and it’s gotten to the point where Alex now has consultants managing consultants. For a place so synced in its culture, how could this be? How could we have all these outside people managing these other people without having gone through all the necessary things to become a Bridgewater citizen? . . . How is Alex ensuring the consultants acting as managers are managing in a principled fashion and holding the bar high enough?

In raising this issue, Rohit is doing exactly what every person, regardless of rank, is expected to do at Bridgewater. In fact, it’s called an act of good citizenship to call out things, even the smallest things, openly and directly if you believe someone is acting inconsistently with one or more principles guiding the company. Then diagnosis can begin interactively via the issues log, and everyone can determine what is true and act accordingly.

In response, Alex pushes back on Rohit’s believability.

Not sure how Rohit is believable in the organizational design at all. This is a well-probed design and a much longer discussion of the use of CM [consultant-managed] resources in all sorts of roles of staff augmentation. As you recall, I was a CM myself at the start of my tenure here.

In reviewing this unfolding back and forth in the log, Jensen sees a classic managerial problem, one that applies to Alex and to many others. “We would take that as a response from authority, rather than a response that we would expect from logic,” he explains. “Okay, maybe the design does make sense, but why does it make sense? So, we see Alex deflecting the question instead of dealing with it. Alex is saying, ‘Just believe me because a lot of people have looked at this decision.’ That’s not an acceptable answer at Bridgewater.”

What is someone in Rohit’s position expected to do in response? Certainly not just let it go. Rohit sees Alex’s response as unsatisfactory, and so he uses the Dot Collector to share feedback on Alex’s actions. He indicates that Alex is violating one of the key principles: being “assertive and open-minded at the same time.” Rohit writes his reason for this assessment:

When I issue-logged Alex regarding consultants acting as managers, he was deflective, and he didn’t help me understand the issue at hand. Instead, he focused on my believability and [my] severity rating of the issue.

At this point, Brian, who is Rohit’s manager and the department head for research, reads the exchange in the issues log, sees Rohit’s dots about Alex in the Dot Collector, and intervenes.

As always, of course, I don’t know what I don’t know, so I am just calling out what I see. I’m going to write a lot here, because I think it is important. I doubt you will agree with my perceptions below in their entirety—please take them in the helpful spirit in which they are intended.

One, the specific issue that was logged—I don’t know if it’s a problem or not . . . I certainly don’t know, Rohit doesn’t know (and he seemed to acknowledge that).

The more important thing to me in terms of “what to take from this” is that . . . you [Alex] are taking an issue log in a way that is far different than it is intended to work. It is not an attack that needs to be defended. An issue log is a question—a perception that someone is generous enough to share with you rather than holding to themselves so that the right RP [responsible party] can use it as “fuel for improvement” . . .

Rohit doesn’t need to write this. He can keep his head down and do his job. But we ask him, beg him, demand as a BW citizen that he call out badness when he thinks he perceives it. We don’t ask him to be perfect—we ask him to do his best to balance open-mindedness and assertiveness . . .

The last thing I ever want someone to feel when they issue-log me, my responsibilities, my people is that I or my people are being defensive . . . because that is most likely to shut down the improvement fuel pipe I desperately need.

After going into greater detail to analyze Alex’s and others’ original responses, Brian then circles back to explain what the payoff might be for Alex, if he can turn this interaction into an opportunity for improvement:

Because I could imagine that if you make change at this level (less defensiveness, in fact a real focus on taking input and understanding it), you will not only get better faster, but you will create better, more dynamic, engaged, and fruitful relationships with your customers.

As we see this dialogue ripen, it’s worth taking a moment to ask, What’s really going on here? What does this exchange tell us about how people at Bridgewater work, as a habit? Brian is aware that he’s expected to help Alex address what Brian sees as a recurring pattern of defensiveness. Part of Brian’s job at Bridgewater, through the practice of issue-logging, is to expose evidence about Alex’s limiting behaviors and mind-sets so that Alex can grow. Alex’s job requires him to participate in that process with an open mind.

And what does Alex make of all this? He reflects on what Brian has said and pushes himself to step back from the situation to diagnose what may be going on and understand how it relates to other patterns of behavior that may limit his effectiveness:

Brian, thank you for the feedback. As a colleague and fellow department head, I appreciate the rapport we share and your perspective. I am totally open to my not seeing this in a good way . . . Here’s what I heard you say in your feedback to me:

Consistent with my style and what is in my BBC [baseball card—more on that in a moment], my initial “amygdala” response tends toward defensiveness and overconfidence in the moment with other watch-out-fors including [the lack of] encouraging others to probe, more assertive than open-minded, [not] seeing multiple possibilities . . .

So let me reflect on the potential “take-aways” of this case which I now see more clearly represented by the following questions:

- What is true in the information I’m receiving?

- How can I use the information, if true, to iterate my machine (people and design)?

- What does this information tell me about my clients and the quality of service that [we] share with the community?

- Is this possibly a teaching moment?

Alex is now framing this exchange in terms of what Bridgewater would describe as the higher “you” of “two yous.” There is the you that is in the middle of the action, experiencing the triggering threat to the self, reacting to the threat defensively; and there is the higher you, a part of yourself that can step back and reflect on your actions as part of an ongoing self-system that consistently generates those actions. In our language of adult developmental psychology, we would call the insight of the “higher you” a case of moving what was subject (what we can only look through) to object (something we can now look at). Alex sees that even though he has a pattern of acting this way—a documented pattern—he does not have to be always in its thrall. His questions do not conclude his process of learning, but recognize that there is another way of being that he can construct if he can answer those questions.

The Baseball Card

What is the baseball card (BBC) Alex refers to as a source of information about his pattern of behaviors? What can it reveal to us about another essential practice at Bridgewater? Together with collecting dots, issue-logging, and other tools, the digital baseball cards for each employee form a dynamic system for spurring people to wrestle with their limitations.

A baseball card, as Jensen describes it, forms “a map for how to get you from where you are to where you want to be.” The baseball cards, electronically accessible to everyone, integrate all kinds of data about what a person is like—testimonials, the feedback dots, personality inventories (like the Myers-Briggs), surveys of what people are good and bad at (which include forced-ranking exercises). And as you might expect at a successful hedge fund, the company doesn’t place all its eggs (or data points) in one basket. Jensen explains: “We’re connecting information from multiple streams on people. You can’t rely on any one piece of information, or any one information source, to tell you the truth about people.” The baseball card allows anyone at Bridgewater to see where a person’s demonstrated capabilities stack up against all the principle-driven qualities required for success in any role, benchmarked for the person’s given level of responsibility in the organization.

What jumps out, at the top of the display of every baseball card, is the crisp synthesis of what the employee has demonstrated she is reliably good at doing (her “rely-ons,” shown in the BBC in green) and her areas of weakness (her “watch-out-fors,” shown in red). Alex’s baseball card, like all BBCs, lays out succinctly where he can be trusted and where there are concerns, crystallizing in a few top-line points all the accumulated data that runs through the data visualizations and evaluative comments of the whole baseball card (see table 4-1).

TABLE 4-1

Alex’s rely-ons and watch-out-fors

| Rely-ons | Watch-out-fors |

|

|

Note: In the Bridgewater baseball card, rely-ons are shown in green, and watch-out-fors are shown in red. |

|

You might think that seeing a description of one’s “watch-out-fors” so openly documented could be anxiety-provoking. You’d be right, according to people at Bridgewater. Jensen explains, however, that the card is essential for helping match people to roles and that a baseball card is not a fixed description:

[We] build out that picture [of a person], so that you can know, every time we transfer somebody or move them through the company, you get this baseball card, so you can know if you put this guy in a circumstance, here’s what he’s likely to be like. And you can connect people with jobs [based on] what they’re capable of doing . . . Some people see their baseball card as their destiny—like, “Oh my God, I’m bad at this. I’m screwed.” And that kind of person will never get the most out of life . . . There are two ways to deal with your weaknesses. One is to try to learn and get better at them. That’s one path that you could be pursuing. The second path is, How do you get around them? How do you use others to get around your weaknesses so you can get to your goal? And so if you can stare at reality, accept what’s true about yourself, have others helping you do that, you have a map helping you get to success. And that’s really what our baseball card is intended to be.

For Alex, then, the baseball card serves to reflect evidence about what he is like, how he does his work, how he leads, and where people feel they can count on him and where they can’t. He can take this source of evidence as grist for the two kinds of self-improvement Jensen proposes. He can overcome those limits through learning, or he can develop ways to use others’ help to compensate for his weaknesses (what people at Bridgewater call “guardrailing”).

More broadly, the cultural practices we’ve discussed in this section close the gap between how a person sees himself and how his colleagues see him. This is one way that a DDO can create the conditions for people to feel at home with the work of self-improvement. If having weaknesses is normal—universal and documented for everyone—then acknowledging and working to overcome those limitations are much less frightening. Every senior leader at Bridgewater also has a baseball card openly shared with the entire company. There are usually as many or more watch-out-fors as rely-ons in each of those cards, too.

Other Practices: the Daily Update, the Daily Case

In addition to probing and diagnosis, which happen constantly around the campus, and the use of the Dot Collector, baseball card, and issues log, Bridgewater makes a daily practice of learning and reflection in other ways.

One practice is the submission of daily updates to one’s supervisor. Although regular supervisor check-ins aren’t unusual elsewhere, the Bridgewater daily update makes each employee’s process of getting in sync with his manager a public act. Anyone can see anyone else’s daily update. What kinds of updates are shared in this daily communication? Above all, the updates give people an opportunity to reflect on what they are learning about themselves, any pain they’re experiencing, and ways they’re grappling to improve their application of the principles. At their best, these updates prevent gaps from forming between an employee’s interior struggles and a manager’s understanding of those struggles.

Another practice is part of every employee’s learning each day. Called the “daily case,” this process is, according to Bridgewater leaders, “the calisthenics of our culture.” For about fifteen minutes every day, people review an actual multimedia case study of a teachable moment in the life of Bridgewater’s culture; the case combines video and snippets of digital documents, e-mails, or other artifacts. Cases are something like teaching cases in a professional school. For example, the details of the case of Rohit, Alex, et al., described earlier in this chapter, are the perfect material for a Bridgewater case.

What happens in the fifteen minutes of daily practice with a case? Employees are asked to review the materials and are asked a series of questions about what they would do in the situation and why. For Jensen, this is both an opportunity for people to exercise and also a chance to gather data about what people are like: “[The daily case] reinforces the exercise of connecting the day-to-day to management,” he says. “It’s a quick case study where people get a bite of the culture. We see how they react to it. And that helps us fill in an understanding of how they would be in those situations.” The result is an entire organization engaged with a similar professional curriculum, one that encourages practicing the application of the principles and collects yet another source of evidence about the mind-set of every person in the company.

From the individual experience of probing in every one-on-one meeting, to the technologically integrated processes for discussing dots, issues, and baseball cards, to the companywide practices of daily updates and cases, Bridgewater has built an ecosystem to support personal development. The system helps everyone in the company confront the truth about what everyone is like.

Next Jump: “Character Is a Muscle”

When Next Jump studied how things fail, the leaders concluded that the number one recurring pattern was the inability of people to manage their emotions, what the leaders call “character imbalances.” This inability, they observed, leads to poor decision making. Chief of Staff Meghan Messenger says, “Most companies have super-competent execution people, not super-competent decision makers.”

Next Jump discovered that the imbalance between the character traits of confidence and humility led to emotional tantrums, outbursts by the overly confident (or arrogant), and paralysis by the overly humble (or insecure). The growth in the company’s leadership took off as leaders discovered and consistently practiced the development of character as a muscle that could be exercised, helping people become more humble or more confident. (They even created a wallet-size card with tips or reminders for practicing your less-developed sides. See table 4-2.)

TABLE 4-2

Next Jump’s wallet card for practicing your backhand

| Overconfident/Arrogant | Too humble/Insecure | |

|---|---|---|

| Better me | Listening more (being last to speak in meetings) | Speaking up more (being first to speak in meetings) |

| Being less aggressive (slower to launch) | More aggressive (sooner to launch) | |

| Being more vulnerable | Being more courageous | |

| Being more disciplined | Being more optimistic | |

| Better you | Take more advice | Give more advice |

| Nurture more | Coach more |

Next Jump leaders believe in the transformative potential of carefully designed rituals. These are not rituals for their own sake, but for the sake of keeping people in the groove of working on their character. Let’s take a look.

Talking Partners

As we’ve mentioned, a typical day at Next Jump begins with people checking in with each other in pairs known as talking partners (TPs). If you were to listen in on these discussions, often held while the partners eat breakfast provided by the company, you’d quickly observe that they don’t have a structured agenda, although there is a common purpose for the meetings, which CEO Charlie Kim describes as “co-mentorship.”

Each TP meeting is organized around a triangle: meet, vent, work. Meet signals the need for the consistency of meeting every morning, getting into a daily ritual of the practice. Venting involves “getting the toxins out,” as Next Jumpers say. Anything from your home life or work life is fair game for discussion; the theory is that to admit yourself as a whole person, warts and all, into the workplace, you need a place that honors feelings of frustration and anxiety as part of who you are. Venting also gives you a structure for lessening the hold of negative thinking on your attention.

The work component of the TP triangle is one that many Next Jumpers describe as having the greatest impact on their growth. Partners are expected to push each other for greatness, set high expectations, and help each other see pathways, both in general and for the day’s work, to greatness.

For example, let’s look at talking partners Nayan Busa and Lokeya Venkatachalam. Recall that you met Busa in chapter 1 at Next Jump’s Super Saturday, when he welcomed a room full of job candidates to Next Jump’s headquarters. Now we join him in a different context, as he describes his talking partnership with Venkatachalam.

In some ways, we are brutally honest with each other. We are past that stage where we are patting each other on the back and saying, “Okay, good, good.” And we actually care for each other. And each knows that the other cares. If she was going in the wrong direction, I would just say, “You’re going wrong.” . . . So, I am honest with her and giving critical feedback when necessary. And I point out the things that I like that she is doing. She is making systematic improvements, and I make a point to tell her that, so that it doesn’t go unnoticed to her. And it’s the same in return.

Venkatachalam confirms the importance of her morning routine with Busa. We interviewed them on a day when Busa was scheduled to give a presentation at a monthly development event called 10X. (We return to the important practice of monthly 10X meetings shortly.) Venkatachalam gives us a glimpse into the way the TP relationship can provide a context for growth.

So, this morning, I was telling Nayan as he was preparing for the 10X, let’s not worry about it. And I told him, “How about you practice your storytelling, which you’ve been struggling with? Just pick two stories you want people to take away.” And that kind of eased his mind, as he was worrying about too many things. “Hey, work on the concise presentation and your storytelling. That’s all you can do. Don’t worry about anything else.” And I think that kind of guidance we provide to each other, those are the moments we feel, “Oh my God, if we didn’t have this, I would miss a big thing in my life.” The peer talking partners understand each other’s struggles, which we wouldn’t get otherwise . . . It’s kind of ongoing weakness correction and how we work on it.

Certainly not all talking partner pairings are as successful a developmental match as Venkatachalam and Busa have turned out to be. These pairings are not permanent, though, and managers regularly reassign members of TP pairs. As they do, they make sure that people are paired with others who will push them, making every effort to match someone who leans arrogant with someone who leans insecure.

The Weekly Situational Workshop

Talking partner pairs become the building blocks of another practice at Next Jump: the situational workshop (SW). The leaders believe that this workshop is among the most effective things they do. Every week for one hour, five people meet: two different pairs of talking partners, along with a more experienced colleague acting as a mentor and coach. SW is a scalable program. Each recipient of coaching is expected eventually to coach four others; the students become the teachers.

Kim identifies what makes this kind of weekly workshop structure powerful.

At this weekly workshop, each of the four of you describe some challenge you’ve met in the week and what you’ve done to meet it—or not. You might not be sure if how you handled the situation was optimal or not—SW is a reflective exercise. The mentor-coach is there to encourage you to reach a higher level of self-awareness, so that you might identify new options for responding to similar future challenges and so avoid reacting in the same old way. You share your situation, and the coach can say, “You thought your choices were this and this? There were a lot more choices you didn’t see.” Over time, you see people growing immensely from these weekly sessions. We’ve even replaced most manager meetings with situational workshops.

The dilemmas that people raise in an SW are varied but typically deal with people’s backhands (limitations). We’ve heard people talk about a range of specific challenges that point to different potential limitations or triggers: whether to give another person unsolicited advice, how to get over the desire to have a perfect result rather than an acceptable result, how to be more effective in managing time, how to not choke in a high-pressure situation, and more.

As Kim explains, an SW’s purpose is to focus “on the training of judgment, rather than on technical training.” As a result, the discourse and pace of an SW can be a bit surprising to a first-time observer. People identify problems of practice, but the coach’s response is rarely direct problem solving. All Next Jump practices seem to be designed with an awareness that if you solve a problem too quickly, it is certain you will be the same person coming out of the problem as you were going into it. You won’t change. And if you don’t change, you’ll most likely reproduce new versions of the same problem you think you solved earlier.

Accordingly, the coach in the SW is more likely to let the problem “solve you” rather than the other way around. The coach might say, “What does it tell you about yourself that you froze in that kind of situation?” The emphasis is on hearing numerous situations rather than spending a long time on any one of them. Keeping in mind this is happening every week for every employee, the result is something more like Bridgewater’s dot collecting. A great many data points are being assembled; no one of them is a big deal, but the cumulative experience is that everyone becomes aware of patterns they would not otherwise see.

From a developmental perspective, an SW has several important features. First, it builds on the relational foundation of the talking partnership, giving people someone to listen in on their learning who will hold them accountable and look for opportunities to help apply their learning. Just as important, SWs are about cases drawn from the flow of your own work life, and not lessons from fictional exercises or abstract business concepts. Situations are meaningful to the person seeking coaching, growing as they do from live preoccupations or nagging recent experiences of discomfort, triggering, or failure. Moving their thinking, feeling, and behavior from subject to object, people are helped to look at lenses they were formerly able only to look through.

At the same time, the SWs strengthen the dimension of home (the developmental communities that support a particular, personal kind of learning on the job). It is not lost on Next Jump participants that the most senior leaders are full participants, investing the time they are, every week, to be helpful to everyone. Keep in mind, as well, that you go through a weekly SW with your daily talking partner, someone who stands to give you better counsel over breakfast each day if she better understands the range of feedback you’re getting in the workshop. To be sure, there are lots of places someone at Next Jump can get coaching—at the end (or during) any meeting, in reply to an e-mail, over breakfast. The SW is a regular part of the rhythm of the workweek, ensuring that it will happen predictably for everyone. Before you know it, Next Jumpers become more mindful, traversing their week looking for situations to be brought up in their weekly SWs. And if SWs have begun to replace many management meetings—even though they’re not “progress checks” or “behavior resets”—it may be that managing the interior is a powerful way of managing the exterior.

The Monthly 10X Factor

Another companywide practice follows a predictable monthly rhythm: the 10X Factor. Each month, for ninety minutes that command the attention of the entire company, ten Next Jumpers give a short presentation on their contributions to the company. The name of this developmental opportunity started as a play on the television show The X Factor. Graphics circulating within the company and posted on the walls announce, “The World Will Be Watching,” a play on a meme from that show. In fact, the entire staff at all four global offices is watching, in person or via livestream.

10X presentations are public, shared opportunities for growth. In the five-minute presentations, a Next Jumper can talk about his contributions to one of two things: the company’s revenue or its culture. Then everyone rates the presentation on a 1 to 4 scale via mobile app, and then a panel of judges, often including Charlie Kim or Meghan Messenger, scores the presentations and gives live feedback.

Although the feedback from the judges can sometimes be pointed and harsh, it is tied to helping each presenter get better at talking to others about his struggles in ways that help everyone learn. Here is a real example of one judge’s feedback:

Your results are clear. You’ve taken an evaluation process that used to take three months or more and gotten it down to ten days, with better quality. The visual evidence you show is compelling, the getting rid of the old paper process. But tactically, you missed opportunities here. You should have focused less on what you did and more on how you did it. You should be helping to educate people at 10X. How you did it. I think this was all about you having the courage to fail in iterating and training. You robbed everyone of an insight that could have helped them see how to implement that courage to fail.

It’s crucial that people aren’t being celebrated at 10X for their literal outputs or results on the revenue or culture side. The results matter, of course, but they aren’t why the company comes together once a month to focus intently on ten employees’ stories. Instead, the Next Jumpers with higher scores earn those scores because they reveal through stories how they’re working to overcome a personal limitation in order to generate better results in the business and its culture. It’s a reward for bravely revealing your process of working to transcend limits, the work of shifting your mind-set, and not a vote on the outcomes (exactly the same as Bridgewater redirecting its admiration to “struggling well”).

This experience feels high-risk for all the presenters. For any individual, it’s not a part of the regular workweek, and so even though it is a chance to reflect on and share work on yourself, it’s a big enough event to make your heart beat faster and your palms sweat. Harsher feedback is reserved for presentations about culture projects. After all, contributions to the culture are designed to be practice grounds for learning and self-improvement. Next Jump uses the metaphor of projects that are above the water line (the culture) and those that are below the water line (the revenue). If you steer an ocean liner through an icy sea, an iceberg strike above the water line won’t sink you, but a strike below the water line can cause the ship to founder. Although practicing is an everyday mantra, cultural initiatives present greater personal risks and greater freedom to fail in pursuit of excellence. And 10X itself is a cultural initiative, one that was started by twenty-something employees, who (taking off on a talent-oriented reality television show) led the design, implemented the process, and coached others to take it over and improve on it.

In chapter 1, you saw other Next Jump practices that connect to the work of daily talking partners, weekly situational workshops, and monthly 10X meetings (recall Jackie’s 10X presentation about her cultural contributions, and lack thereof). These practices include the Super Saturday hiring process, the Personal Leadership Boot Camps for onboarding new staff and developing experienced staff who are struggling, and the many forms of work on Better Me—giving back to people in order to enhance every employee’s feeling of doing meaningful work. These practices operate together to create an environment where working on one’s character, as Next Jump describes adult development, is a habit for everyone.

Decurion: “Ten Times More Capable Than You Think”

When you spend time in meetings at Decurion, you quickly discover that setting the context is crucial. Decurion leaders talk openly about the need to “align intentions” up front, especially before tricky conversations—ones likely to heighten people’s sense of vulnerability or to reveal conflicts.

Aligning intentions is more than being sure people know the meeting agenda or even the meeting’s goals. It is those things, but it is more. It is a signal that people are about to practice doing something hard, something they may want to avoid because of fear of loss. And so, rather than enter that work on autopilot, carrying forward your state of mind from another setting or task, it’s a time to connect to the deeper purpose that calls those around the table to the conversation. In a moment, you will see how Decurion uses a subset of its practices to enable people to stay connected to the needs of the business and to their own flourishing.

As you explore the practices of Decurion, you will take a close look at how the ArcLight cinemas specifically create these conditions. We think that focusing on the practices in the theaters—even if other parts of the company could offer similar insights—offers you a unique perspective. In the knowledge economy industries where Bridgewater and Next Jump operate, highly educated employees work in high-wage jobs. In contrast, working inside the theaters is, for most, a different kind of role, but employees’ personal growth is no less powerful. ArcLight crew members create meaningful guest experiences, and their roles are part of a service-oriented, retail sector.

But what distinguishes industries, contexts, and roles in their potential for developing people, we think, is far less important than what transcends those boundaries. For us, and we hope for you, it is just as instructive to understand how a company can create a rich culture to support the psychological development of young people working in a cinema as it is to see similar work for engineers and financial analysts.

Touchpoints

An ArcLight location on a Saturday night is buzzing with activity. Guests stream in, passing through a grand lobby to enjoy the latest blockbuster or independent film. They take their reserved seats in theaters designed for comfort, minimal distraction, and heightened attention to the quality of sound and image. Shows begin and end at regular cycles.

Amid this activity, just below the surface of the guest experience, a series of interlocking practices helps keep workers’ development at the center of a thriving business. In quick daily meetings with each crew member, called “touchpoints,” managers try to connect members’ daily work experience to their personal growth and larger goals. In regular pulse-check huddles throughout the evening, groups of crew members and managers give and receive feedback on how the floor operations are going and how they can be improved.

In the crew offices hang huge “competency boards,” where colorful plastic pins hold evidence of every crew member’s level of demonstrated competency. The competency boards are modified to show individual areas of growth in the capabilities of the crew members. Earlier, the theater general manager and other shift supervisors spent time scheduling for the next week, matching business needs to new job rotations and checking in about each person’s level of readiness for new challenges or continued practice.

A touchpoint, then, is a frequent, focused opportunity to connect your own growth to the work you’re doing. Touchpoints are held for senior executives and for theater crew members alike. Decurion leaders believe that work is inherently meaningful, for everyone, and these touchpoint conversations are like the daily needlework of development, threading the personal through the fabric of working life.

Think for a moment about how rare it is in most organizations to have a conversation about what is meaningful about your work, review any struggles you’re having, and discuss aspects of your growth. For nearly all of us, this might be, at best, a quarterly or annual conversation as part of a formal review process. At Decurion, “developmental performance dialogues” (as they are called) also happen, but they are in addition to the more-frequent touchpoints.

Crew members told us about the regularity and importance of touchpoints. Often, they talked about the ways that the conversation helped them see how their work connected more clearly to their own hopes for future growth.

ArcLight crew member Cristina, for example, told us that she shared her goal of becoming a film set decorator. After that touchpoint, her manager gave her the chance to join a team to create the decor for special events held at her location. In Cristina’s eyes, ArcLight valued giving her opportunities to connect her own goals for the future to her present work in the theater.

Cristina’s manager, Michael, sees touchpoints, in part, as a way to help crew members appreciate what they can learn at ArcLight, knowledge that can help them realize their own aspirations. Even if someone does not stay at ArcLight for a career, Michael says, each crew member can learn many of the aspects of running a successful business, and these skills are transferrable to almost any pursuit. Whether starting from the personal goals of a crew member or from the sincere belief in Decurion’s business as a laboratory for more-general self-development, managers like Michael draw on various means of connecting the growth of subordinates to opportunities in the business.

Line of Sight

As in meetings at all companies, sometimes touchpoints get squeezed for time, and sometimes an individual touchpoint isn’t particularly productive. But touchpoints, at their best, have a deeper design that simultaneously serves the interests of the business and the employee. Decurion leaders call this deeper design “line of sight.” This metaphor is another image of alignment, related to the call for aligning intentions at the start of meetings. Decurion managers look for line-of-sight opportunities every day to help members “connect the why through the what to the how.” In other words, built into the style of touchpoint coaching is a practice of questioning, rather than merely giving status updates.

For a crew member, this may mean that a dialogue with a manager enables her to see that her progress in, say, cash management competency (the how) was reflected in shorter guest lines and greater accuracy (the what), and that this contributed to a markedly better guest experience and therefore a positive impact on the business (the why).

Pulse-Check Huddles

If we return to the floor of the theater’s Saturday night operations, we find another of ArcLight’s practices, “pulse-check huddles.” The fast pace of the changes between show sets makes the conversations in the theater especially energetic. In some ways, pulse-check huddles are quintessential experiences at Decurion, and they make salient the way people can work on themselves at the same time that they’re working on improving the business. (In chapter 5 we explore in detail the way the DDO treats these two goals as one thing.)

A huddle happens regularly during a shift. Managers and crew members come together for about ten minutes before or after a series of theaters is being reset for the next round of screenings. As they meet, the participants typically do things employees in other businesses might do—make sure that everyone is aware of operational conditions (such as big movie premieres), ticket-sales targets, and the percentage of filled seats throughout the location. But these participants are working on additional skills—giving and receiving feedback effectively and connecting their own roles to the larger organization.

What happens in a huddle? Here’s a typical example. After the group members come together, one gives another feedback about the negative impact on guests of not having the largest theater ready to open at the anticipated time, asking that the two of them work together to speed the turnaround for the next set. A shift leader notes that someone—let’s call her Angie—is working on getting her “blue pin” (a mark of competency for a specific role) and asks that everyone support her tonight, including giving her feedback about how she’s doing.

When the huddle breaks, as people move to different parts of the location to quickly resume their ticket scanning, cleaning, ushering, and other duties, the general manager and the shift leader stay behind for on-the-spot feedback. The manager explains that in the future, it’s important to say exactly what competency Angie was working on (“usher scout”) so that everyone knows how they can be more helpful. It’s about making sure the feedback is as useful as possible, and not only about supporting Angie in general.

For developmental purposes, the most attractive aspect of the huddles is that the conversations operate on at least three levels. At the first level, crew members are talking about how to learn from and improve operations on the spot, while the data is fresh and course corrections can be made. A second level is the direct practice of giving and receiving feedback, crew member to crew member. Like many people in other workplaces, most crew members, on arriving at ArcLight, have little experience in giving feedback to someone at work. The huddle provides a routinized way to practice this skill in the context of a regular structure where that behavior is safe and expected. Finally, there is a third level: getting feedback on the feedback. Crew members involved in giving feedback get coaching from their managers on how to improve.

Huddles put crew members in the position of looking at the operation as a whole, coming together often to take stock of the entire theater as a system—much as a general manager would be expected to do on a walk-through of the location. In this way, huddles allow crew members to be businesspeople first rather than be embedded in their assigned roles. The huddles put into practice what ArcLight means when it says “the crew runs the business.”

The Competency Board

The aforementioned competency boards are literal poster boards hanging on the walls of every theater’s back-of-house area, prominently displayed as one of the first things people see when they arrive at work, take a break, or duck behind the scenes during their shift. Every crew member has the potential to gain certified competency in a series of about fifteen roles. As they achieve each competency, theater managers publicly honor it by placing a colored pin in the relevant space for that crew member on the competency board. Confirmation with a blue pin comes only after a crew member demonstrates competency over multiple shifts and asks to be evaluated for possible pinning. (A green pin marks an interim step of growth for a competency not yet formally certified.)

Early in a crew member’s tenure, some roles serve as a first tier with a shallower gradient to getting pinned. Other roles involve more complexity and integration of theater operations, and getting pinned for those roles offers both a sense of capability and, to Decurion’s leaders, data about the pipeline of potential leaders.

Standing backstage near a competency board feels a little like hanging out in a communal watering hole—a place where attention and conversation are focused as people stop to look at the board, seeing whether anyone has gained a new pin. The message is unmistakable: growing people into greater levels of skill, at the very least, is a focus of this community. Moreover, that growth is not a private set of goals between you and your manager but rather a public resource. Everyone knows what others are working on, and, as a result, everyone can step forward with support and feedback. Everyone also knows what kinds of capability, manifested in the roles, are required across the organization for the business to run effectively.

The competency boards are part of a system of tracking data about learning and development that saturates the company. At weekly meetings of theater management, in addition to traditional business metrics, the group tracks the share of crew members who are ready to enter a management role. Knowing clearly where each person is in his development is part of Decurion’s commitment to the stance that “everyone is on a developmental path” and “everyone is teaching and learning.”

An essential part of tracking individual growth is the creation and calibration of developmental pulls. By “pull,” managers mean a kind of challenge that, in itself, motivates growth. A person having a certain level of capability is matched with a demand (such as the skill requirements of a new project) that exceeds the person’s current level of capability. The conditions for a strong developmental pull are created when someone is placed in a role or responsibility she hasn’t mastered or for which the complexity of the task is slightly above her current capability. With the right amount of support, along with the challenge provided by the pull, growth is a natural process, one in which the person (or group, or division) must improve in order to meet the demand. This is part of assuming, as Decurion leaders say, that “people are ten times more capable than you think they are.” In other words, the leaders hold a fundamental belief that people will grow, and can do more, with the right structures and conditions available to them.

The competency board works hand in hand with a scheduling practice that maximizes opportunities for developmental pull. Each week at every theater location, the location management team collaboratively plans the work schedules for every shift and role. As a general matter, Decurion executives believe in the value of frequent changes of responsibilities (“Don’t let things settle,” they say).

Decurion Business Leadership Meetings

A final practice brings all parts of the company together. Once every three to four months, depending on the need, the entire business leadership—every manager—attends a daylong DBL (Decurion business leadership) meeting. Most of the meeting takes place in one circle, with everyone able to see everyone else.

A DBL is a slower, more deeply reflective version of a huddle. There are no outside facilitators.1 A DBL usually begins with individuals checking in, sharing the worries and excitement that have a hold on their attention, so that they can acknowledge these concerns and ideas and allow others to better understand what’s going on interiorly. Senior leaders align intentions by foregrounding the issues that now require the entire community to act together as businesspeople first, rather than in the guise of their roles—for example, a real estate deal that will stretch the company by its scale and complexity, a national expansion of the theater circuit, the plan to launch a new business line the company has no direct experience in (yet).

Throughout the day, there are whole-group discussions of the requirements of business goals and the ways that parts of the company will need to stretch in capability to achieve business growth. The DBL may also include small-group discussions arranged by division, and celebrations of individuals who exemplify the values of the company. Leaders may share and lead a discussion of an evocative work of art, such as a poem, that heightens members’ awareness of the challenges that lie ahead and encourages them to take heart in believing that they can grow in the ways that are required.

Life at Decurion, as at Bridgewater and Next Jump, provides a range of opportunities for development. The opportunities span various scales of routine—the hourly, the daily, the weekly, the monthly. They provide safe, trusting, and consistent places for this work within widening circles of community—from personal coaching, to team developmental dialogue, to shared organization-wide learning experiences. In that spirit, we borrow the idea of a “crew” from Decurion in observing something more general about DDOs. Working on oneself as part of a job requires that everyone, from the CEO to entry-level workers, has a crew to practice with—a trustworthy group of people who can be counted on as a source of challenge and support.

Five Qualities of Practicing in a DDO

Let’s step back now from the practices you’ve seen in each of the DDOs. It’s easier to see the differences rather than the similarities, so at this point let’s quickly highlight several deeper commonalities in the developmental practices in these companies.

- Practices help externalize struggles that are interior. In each of these companies, the practices provide access to what we call the interior life. When the routine assumptions of the business world do not allow people to articulate and examine their limitations, there’s little hope they can ever overcome them. The practices at Bridgewater, Next Jump, and Decurion represent a range of ways to allow people to disclose and work on parts of themselves that would typically be off-limits. Only by revealing to others and ourselves how we think, what we feel, and where we’re stuck can we construct, over time, new ways of being.

- Practices connect the work of the business to working on ourselves. From issues logs to scheduling at ArcLight, practices in a DDO provide tangible ways for people to improve as the business grows. Rather than separate development activities (such as external coaching or sending high-potential employees to an executive MBA program), the DDO practices give people opportunities to work on improving themselves as part of meeting their job requirements. These activities are one in the same, rather than two things.

- Practices move us from focusing on outcomes to the processes that generate outcomes. In the practices we’ve surveyed, feedback is oriented not toward correcting an instance of behavior but toward shifting the mind-sets that produce the behaviors. Practices in a DDO do not reward or punish results independently of the processes that produced them; instead, they target improving the thinking that generates the results. When you’re practicing inside a DDO, you are less concerned with the final score in any one game and more concerned with improving the way you play. Charlie Kim of Next Jump is often heard saying, “We focus on the long game, not the short game.”

- Language is a practice, and it creates new tools for a new paradigm. DDOs are meaning-making cultures—cultures of dialogue. (In these organizations, you’ll find many fewer PowerPoint slides and one-way presentations in meetings.) DDOs also develop their own insider language of practice (backhand, dots, pulls). Practices can seem opaque to outsiders, especially as a DDO matures and its increasingly fine-grained, coachable distinctions around practices become more elaborated. We don’t see this as obfuscation. After all, you can’t coach someone without a language for the coachable elements of performance. And remember, a DDO’s priority is to strengthen its culture. These communities are making a trade-off. They will give up some of the default language of business in order to help people engage in practices they see as more powerful. To many outside, this makes the organization’s discussions of its practices sound peculiar or even cultish, but they might miss the unique power that’s released when an organization develops its language of practice.

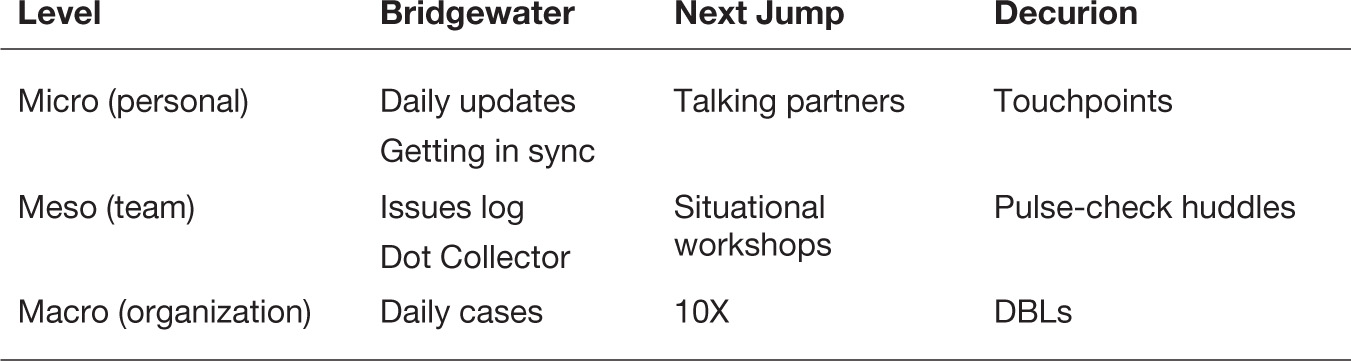

- Systemic stretch involves everyone, every day, across the organization. DDOs get traction with their practices because the organization is saturated with them. As shown in table 4-3, practices are consistently implemented at multiple scales of time and community: daily, weekly, monthly; individual, pair, team, division, company. Rather than a few people having stretch assignments at any one time, we think of the constant all-level, all-the-time nature of practices in DDOs creating systemic stretch. Everyone in the culture is being pulled by challenges generated through the DDO’s practices to keep acknowledging and trying to overcome the assumptions that limit them. Borrowing Bridgewater’s metaphor, every job is a tow rope.

TABLE 4-3

Systemic stretch: integrating practices at multiple levels