“The best use of this island is for recreation”: Resisting the Gambier Island Copper Mine Proposal, 1979–85

Lying in Howe Sound to the north of Bowen Island, mountainous Gambier Island had only about sixty permanent residents by the late 1970s, and to reach Horseshoe Bay and Vancouver they first had to take the foot passenger ferry to Langdale on the Sunshine Coast. Gambier’s population swelled to 600 in the summer, however, and most were determined to preserve the small island (66.5 square kilometres) in as natural a state as possible.1 That goal was threatened in 1979 by the large copper and molybdenum mine envisioned for the north end of the island. The mine ultimately failed to materialize, but the opposition it stirred up from well beyond the island’s property owners ensured that Gambier would be reserved from future prospecting despite the considerable value of its metal deposits. Once again, broad-based environmental organizations were not the leading organizers of the opposition movement, for the campaign was principally orchestrated by a small number of middle-class women. And, rather than focusing primarily on the threat the mine posed to the natural environment, their campaign emphasized the recreational value of the island and the potential aesthetic impact of the open-pit mine as viewed from the Sea to Sky Highway.

Inspired by the example of Bowen Island (see chapter 3), an eight-member committee of Gambier Island residents drafted a community plan (albeit an unofficial one) in 1976 that, according to the Vancouver Sun, envisioned “a mixture of residential, nature preservation, farmland, private institutional, extractive industry, interior park, marine park and forest areas.” Though mentioned, industry would be strictly limited, for the plan called for a moratorium on Crown land timber licences; a ban on the extension of log booming, sorting, and storage; a limit on road construction; and a ban on commercial activity until approved by the residents. To prevent soil erosion, the community plan also suggested that logging be exclusively on a small scale, using selective cutting methods, and with vegetation retained on either side of designated creeks. Reforestation would be mandatory for areas larger than 2.0 hectares (4.9 acres). In addition, environmental assessment would be required for “proposals that would significantly change topography,” toxic agricultural chemicals would be discouraged, and discharge of effluent into any body of water would be prohibited. Covered as well were neighbouring Grace Islands, Alexandra Island, and “unnamed islets within 250 metres of the Gambier shoreline.” Finally, the plan opposed the introduction of a car ferry service while calling for a volunteer fire department, police protection during the recreation season, health centres, and housing for the elderly. Although the authors recognized that their plan would not be binding on federal or provincial agencies, senior levels of government were requested to regard its provisions “as in the best wishes of the community and use them as guidelines.”2

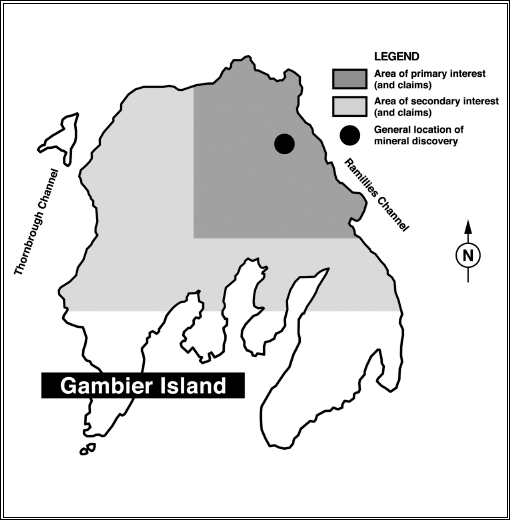

5.1 Map of Gambier Island, 25 October 1979.

The provincial government approved this distinctly progressive community plan,3 which three years later became official as Gambier Island Zoning Bylaw, 1979, but that same year Vancouver’s recently established 20th Century Energy Corporation proposed a multimillion dollar, 480-million-ton copper, molybdenum, silver, and gold mine on the island. Preliminary drilling of twelve holes had revealed copper equivalent grade at 0.47 per cent, which – the Northern Miner reported – was “a tick better than that of Cominco’s Valley Copper Mine which is soon to be brought into production in B.C.’s Highland Valley.” Based on current metal prices, net payable value was estimated at about $5.50 per ton, made up of $2.50 per ton of copper, $2.00 per ton of molybdenum, and $1.00 per ton of silver and gold.4 At current prices, the company claimed in 1980, the mineral reserves would have a value of three billion dollars.5 It had staked three quarters of Gambier’s surface – more than 6,800 hectares (17,000 acres) – but its president, Leonard Zrnic, stated that this was to prevent the island from being overrun by “20 other Vancouver companies which might not be as concerned about the environment as we are.” Zrnic indicated that the mine would be hidden from view by mountains on the northwest part of the island and promised that a reclamation program would “put things back as nice as they were before, if not better.” The open-pit operation would, nevertheless, “require a mill, tailings pond, road, large dock and about 300 workers commuting daily by boat.”6

Spurred by Gambier’s representatives, Islands Trust chair John Rich asked the provincial government to impose a moratorium on Gambier mineral exploration, citing the Trust’s mandate to “preserve and protect, in cooperation with municipalities and the government of the Province, the trust area and its unique amenities and environment for the benefit of the residents of the trust area and of the Province generally.”7 Rich also sought public support by organizing an open meeting in Vancouver’s Devonshire Hotel. Of the more than 300 who attended, all but a dozen stood up in favour of the Trust’s stand.8 The response of R.H. McClelland, the Social Credit minister of Energy, Mines, and Petroleum Resources, was that “Such a moratorium cannot be placed without special legal action, which in my opinion is inappropriate under present circumstances.”9 As for Environment Minister Rafe Mair – who would later become an outspoken environmentalist – he simply stated that there was no ban on “traditional resource uses such as mining” in Howe Sound.10 The Crown nevertheless held subsurface rights, Mair noted, so the Permanent Steering Committee, consisting of officials from various ministries, would examine the mine site and consider social, environmental, and economic impacts before making a recommendation to the cabinet’s Environmental and Land Use Committee, where the final decision would lie.11

Islands Trust had asked lawyer Terence O’Grady for advice concerning its legal position with respect to the banning of mining operations. O’Grady was not encouraging, for his report stated that in giving regional governments the same controls over land use that had been devised for urban communities, the Legislature “did not contemplate for a moment that they would be used to control and even prevent the kind of industrial activity that has always been associated with the more remote and underdeveloped areas of the province.” He added that with many of those areas now accessible for residential and recreational purposes “it seems evident that what was once taken for granted is no longer necessarily so and that priorities are going to have to be established at the provincial government level, no matter how unpopular the decisions involved may be.”12

The government failed to clarify the issue, however, leaving its Environmental and Land Use Committee to commission a recreation and visual analysis by the EIKOS Design Group. The report, released in February 1980, stated that the fact that Gambier was “virtually devoid of roads and commercial development,” and that 60 per cent of the island was Crown land, “suggests opportunities for an intensively managed ‘wilderness type’ recreational experience.” (The association of “wilderness” with the phrase “intensively managed” reflected the technocratic and bureaucratic side of environmentalism.) Aside from access to hiking and camping, the report’s author noted, “the sheltered waters of Howe Sound provide the only major protected boating area readily accessible to residents of Greater Vancouver.” More than 2,700 small crafts were moored in the Sound, approximately 30,000 individuals had rented 8,000 boats from Horseshoe Bay alone the previous year, and 40,000 households in the Lower Mainland owned a boat, yet only 18 per cent of the Sound’s shoreline was readily accessible for recreation and much of that had been taken for other uses.13

The EIKOS report also moved into new territory by paying particular attention to the mine’s potential visual impact, particularly along the island’s ridgelines. Claiming that “A benefit of the experience of natural appearing landscapes is that they provide a value free grounding for personal awareness,” and referring to “visual vulnerability ratings and sensitivity ratings,” the report’s author added that “Howe Sound is unquestionably one of the most spectacularly scenic and perhaps the most intentionally viewed landscape in the Lower Mainland area.” Finally, he concluded that the impact of the mine “should be considered in the context of the limited land base suitable for recreational use within the Howe Sound Region, the erosion of this land base through other established industrial uses and private property alienation, and the increasing demand for recreational opportunities.” In short, Gambier “could be to the Lower Mainland what Stanley Park is to Vancouver.”14

The government was, however, not moved to stop the mining company’s exploration, and another public meeting of approximately 300 people was held in Vancouver’s Devonshire Hotel in May 1980. The chief speaker was Andrew R. Thompson, law professor at the University of British Columbia as well as former chair of the BC Energy Commission and Commissioner of the West Coast Oil Port Enquiry. Thompson argued that the environmental assessment was pointless because cabinet was bound by the preserve and protect mandate of the Islands Trust and particularly by the section of the Islands Trust Act which stated “that lands owned by the province in the islands shall not be developed or disposed of unless the Crown or its agency first gives notice of the development or disposition to the trustees.” “Obviously,” he added, “this requirement is to ensure that any such disposition will conform to the trust objectives.” The question facing the cabinet, then, “is whether it is prepared to override the trust objectives in favour of mining. It is sophistry to pretend otherwise.”15

In addition, cabinet ministers were handed copies of an antimining petition with 4,500 signatures, a number that soon grew to 6,300 from throughout the Lower Mainland, the Gulf Islands, and Victoria.16 Furthermore, resolutions opposing the mine were passed by the municipal councils of Vancouver, North Vancouver, and West Vancouver, as well as the Lower Mainland Parks Association, the BC Recreation Association, the Bowen Island Improvement Association, and the Vancouver branch of the Sierra Club (it was the only major environmental organization to do so).17 New Democratic Party leader and former premier Dave Barrett also expressed his party’s opposition, but, more significantly, provincial Attorney General Allan Williams – who had been outspoken against the Britannia Beach coal port proposal (see chapter 4) – made it clear that he was aware of the “possibility” of a conflict between the Minerals Act, on the one hand, and the Environmental and Land Use Act and Islands Trust legislation, on the other.18

The government nevertheless refused to make a decision before the company presented a stage-one report on the potential impact of the mine, leading opponents to charge that the many thousands of dollars that would thereby be invested in mineral exploration on Gambier ($433,000 by 31 March 1980) would increase pressure on the government to approve the project.19 The Vancouver Sun also suggested that the government might be “gambling on the company’s not finding a viable ore body, thus relieving it of a painful decision. But there is also the possibility that if there is a discovery the government will step over the Islands Trust and allow a mine.”20 Meanwhile, to ensure that no other mineral exploration took place on the Gulf Islands, the Islands Trust asked that a permanent moratorium be placed on mineral and coal exploration in the trust area, recognizing that it “would not apply to existing claims in good standing, and thus would have no bearing on the Gambier Island situation.”21

The mining project was still in limbo in 1981, yet the company’s explorations were sufficiently advanced for it to claim – based on a leaked prefeasibility report by Acres Consulting (“one of the top mining-consultant agencies in Canada,” according to Zrnic)22 – that the 202 million metric ton deposit would be processed at the rate of 40,000 metric tons a day. The mine would not only employ 690 workers around the clock and create 3,500 jobs in the province, it was projected to operate for fourteen years, with an additional two years at a reduced scale to process the low-grade stockpile. The Acres Report also revealed that Lost Lake and most of Gambier Creek as well as part of a recreational reserve would be eliminated, that shellfish and prawn beds in Douglas Bay would be affected, and that by-products would include a pit measuring 1,450 metres by 1,000 metres extending 90 metres below sea level. Furthermore, a 315-hectare tailings impoundment would necessitate the construction of several dams, the largest being 180 metres high. The mine would also consume 40 million litres of water a day, in addition to the 500,000 litres per day needed “for potable supplies,” most of which would be obtained via a nine-kilometre submarine pipeline from the McNab Creek watershed on the nearby Sunshine Coast. The report concluded, nevertheless, that only 8.9 per cent of the island would be disturbed and that the impact on permanent and seasonal residents would be minimal because “virtually the entire population is concentrated in areas distant from the main site.” The company also promised to upgrade hiking trails that had not been eliminated, augment fishing, revegetate a vast area, and set up a publicly administered fund to expand recreational opportunities on Howe Sound.23

These promises did not impress Elspeth Armstrong, landscape artist and former Gambier trustee on the Islands Trust board. She told a Vancouver Sun reporter that she was not against mining as such (her husband was a geologist and they had lived in mining towns), “but the best use of this island is for recreation.”24 In fact, she had compiled a twenty-page unsolicited brief in 1976 calling for Howe Sound to be declared a national recreation area. Armstrong was also the founding director of the Gambier Island Preservation Society which had a signed membership of 2,200 and which distributed 12,000 pamphlets to the public in 1980.25 She told one reporter that commuting to the mine site from the mainland would be impracticable, and the result would be a sizeable settlement on the habitable south shore of the island, with automobiles, roads, a car ferry, and other amenities that would have a significant physical impact.26 But rather than focusing on the environmental argument that had little appeal in the eyes of the prodevelopment Social Credit government, Armstrong emphasized the economic case by pointing to two major studies in 1979 that had stressed the need for more small craft moorage in Howe Sound in order to bolster the tourism and recreation industry.27

The BC Parks Department did, in fact, propose a marine park at Gambier’s Halkett Bay in 1980, raising Armstrong’s concern that it would be considered a trade-off for the mine.28 In 1982, however, she claimed that the many sheltered bays around Gambier offered “easy accessibility and potential recreational use of 8,600 acres of Crown land.” Low-income boaters with no onboard sleeping accommodations would thereby have access to “a recreational opportunity similar to that presently enjoyed by owners of larger cruising boats.” Mines might mean jobs, Armstrong observed, but tourism was the province’s number two industry. In fact, facilities for 500 boats on Gambier would bring in roughly $463,000 in only twenty-five boating days, assuming full occupancy, and merchants as well as marina owners in Horseshoe Bay and the town of Gibson’s on the Sunshine Coast would also benefit.29

5.2 Elspeth Armstrong, 1976.

Armstrong’s two main allies were also women from Vancouver, namely Beverley Baxter who was also a former Islands Trust trustee and Ann Rogers who was the current trustee. Rogers told a Toronto newspaper interviewer in 1981 that the permanent residents “think that if we would just shut up it would all go away,” but Armstrong claimed that only one or two of the residents supported the mine.30 Armstrong, Rogers, and Baxter were supported by West Vancouver’s municipal council and even Social Credit MLA Jack Davis of North Vancouver–Seymour (who we encountered as federal fisheries minister and federal environment minister in chapters 1 and 4, respectively). Davis stated in the Legislature that “The public in the Lower Mainland area and across the Strait of Georgia on much of Vancouver Island will not tolerate the thought of tens of millions of tonnes of mineral wastes being discharged en masse into the recreational waters in Howe Sound.”31 The indefatigable Armstrong also claimed support from nine municipalities, twenty-eight “known” organizations, and thousands of Lower Mainland residents.32 She continued to keep the subject before the public eye as market conditions delayed 20th Century Energy’s attempt to find a resource company partner. Those attempts were not made easier by the resignation of company president Zrnic in the fall of 1981 as a result of his misappropriation of company funds in connection with a European equity financing proposal. The company assured its shareholders, however, that its underlying assets “are virtually unchanged and we are confident that we will be able to take advantage of this fact in the near future.”33

The following year, in 1982, the frustrated members of the Gambier Island Preservation Society took the radical step of filing with the Supreme Court a petition against Islands Trust for failing to enforce the island’s Official Community Plan by issuing a restraining order against the mining company.34 The provincial government announced in April, however, that the 3,480 hectares (8,600 acres) of Crown land would not be subject to the island’s OCP because the lands were covered by mineral claims in good legal standing.35 The fact that Minister of Municipal Affairs Bill Vander Zalm had proposed publicly that the Islands Trust be abolished led Armstrong to charge that his aim was to pressure her to withdraw from the court action that her organization had launched against the Trust.36

Not only did the Gambier Preservation Society refuse to drop the legal action, it added to the court petitioners’ list in October 1983 the names of several Gambier property owners as well as the Camp Artaban Society and the Catholic Charities of the Archdiocese of Vancouver, both of which had youth camps that would be destroyed by the mine.37 (According to the EIKOS report, 7,000 children and adolescents from ten area camps – three of which were based on Gambier – participated in programs on the island each summer.38) John Rich, who was by this time a second-year law student, was nevertheless able to show that he had been far from inactive as Islands Trust chair in attempting to stop the mineral exploration. Between 1978 and 1982 he had written nine letters to cabinet members as well as meeting with the minister of the environment, the cabinet’s Economic Development Committee, and, on numerous occasions, the staff of the Environment and Land Use Committee Secretariat. As we have seen, Rich had also organized two public meetings in the Devonshire Hotel.39

In dismissing the case against Islands Trust, the judge observed that “because of the unique legal situation associated with the rights of a free miner the remedies called for by the petitioners were neither ‘appropriate’ nor ‘available’ to the Islands Trust.” He added that evidence showed that the Island Trustees “bitterly oppose the proposed mining operation” and had made “very concerted efforts to influence the Government to put an end to them,” but there was “no suggestion that the mining company has committed or threatens to commit any wrong.” The judge added, however, that, “There is no doubt that if the project proceeds, it will largely destroy the existing environment of Gambier Island as a recreational resource and with it many of the amenities now enjoyed by the residents and visitors to the island.”40 Though it had lost the case, then, the judgment was ultimately a victory for the Gambier Island Preservation Society because the judge’s comments helped to ensure that the expiry of the exploration leases a year later would be followed by the passage of an order-in-council establishing a permanent mineral and placer reserve over the island.41

Conclusion

Like the protest against developing the site that became Devonian Harbour Park in Vancouver, the Gambier protest was spearheaded by middle-class women. And like the Hollyburn Ridge and Bowen Island protests, the main focus was on preservation for outdoor recreation in a wilderness environment (and on preserving a semirural lifestyle for property owners) rather than on ecological protection, first and foremost. And, finally, like the Squamish and Britannia Beach coal port protest, a principal issue at stake on Gambier Island was heavy industrial development versus tourism. The protest organizers were able to collect a large number of signatures on their petitions, but the fact remains that there was little chance that the mine would materialize. The Social Credit government may have been distinctly in favour of free enterprise but the nearly two decades of antidevelopment protests in the Vancouver and Howe Sound area had presumably taught it that the well-heeled voters who were its natural constituency would not look kindly on the further despoliation of Howe Sound. As Elspeth Armstrong repeatedly reminded government officials, “The unassailable argument for keeping Gambier Island and much of Howe Sound rural in character is its location – 30 miles from a population centre approaching a million people.”42 Hence, the breaking of ranks by Social Credit MLA Jack Davis. Hence, as well, the signals from provincial cabinet ministers beholden to big business that even though they were prepared to wait until the exploration licence had expired, thereby adhering to the rule book, they would prefer not to have a mine on Gambier.