Human Vulnerabilities in Depression

I hope that in this year to come, you make mistakes. Because if you are making mistakes, then you are making new things, trying new things, learning, living, pushing yourself, changing yourself, changing your world. You’re doing things you’ve never done before, and more importantly, you’re doing something.

—Neil Gaiman

Living in modern times requires us to respond to an array of personal challenges that life offers up, whether we feel ready for them or not. These challenges include big life events (divorce, loss, trauma, chronic pain) and the ongoing, moment-to-moment hassles that create stress in daily life (next-door neighbors that yell at each other, traffic jams, the indigestion from having eaten an unhealthy meal quickly, not having money to pay bills). Your job is to somehow navigate these challenges and live a vital, meaningful, purposeful life.

To borrow from a famous saying: Life is one damn thing after another; your job is to make sure it isn’t the same damn thing over and over again. When you run into a barrier in life, the goal is to soften into it and roll with it so that you can continue on…until the next barrier. This is somewhat like floating down a river on an inner tube. You have to relax as you make contact with boulders and stretches of rapid water, and then allow the water to carry you downstream, trusting there will probably be a stretch of calm water somewhere ahead. Unfortunately, this message is not commonplace in our society. We are taught something very different: to resist the experience of pain and to show how strong we are by conquering our emotions. This notion makes us vulnerable to all kinds of problems, including depression.

One major area of vulnerability in depression comes from dealing with the cascade of daily life stressors that are a part of modern living. Ongoing life stressors, large and small, serve to challenge our problem-solving abilities and resiliency. On your journey out of depression, you will benefit greatly from learning to identify risky situations in your daily life that can trigger a depression. The better you become at recognizing and anticipating life events that make you vulnerable, the more adept you will be at short-circuiting the mental sequence that leads to unworkable coping strategies. As we laid out earlier, normal living consists of lots of challenging situations, events, and interactions. In this chapter, we will ask you to look around and see where the triggers are in your life right now.

Most life challenges require us to come up with creative solutions, even while experiencing some level of emotional discomfort. The potential for making mistakes is certainly there. But the potential for learning more about yourself in the process is huge—especially if you cultivate a sense of curiosity, openness, and acceptance of your inner experiences while focusing most of your energy on coping with and/or solving the problem at hand.

A second major vulnerability in depression is that we are all socially programmed to avoid emotional discomfort. This is partly the result of early learning experiences that influenced us without our necessarily being aware of them. From a young age, we receive lots of social messages encouraging us to control our emotions and behavioral impulses. If we failed to do so, we might even be punished. A frustrated parent might have chided you with the threat, “Stop crying, or I’ll give you something to cry about!” Even if you had a good reason for crying, the message suggests that there is something wrong with your crying and you must stop it if you don’t want to be punished. This type of emotional-control training occurs throughout childhood.

Some of your early role models may not have been much help in teaching you how to take an accepting, open stance toward your emotions. They may have tired of battling their own emotions and resorted to using alcohol or drugs, or isolated themselves from others, or taken to overeating. Maybe they came to suffer from chronic depression, relying on medication and dealing with challenges by pretending problems weren’t there.

Another way we learn to use avoidance is by trial and error. We might notice that a certain response (avoiding phone calls that we know will make us upset, for example) seems to help, so we use that response again. What we don’t necessarily realize is that while a response may have worked in one situation, there’s no guarantee it will work in a different situation, or work the next time, even in a similar situation. Or, more important for our purposes, we don’t realize that emotional avoidance might work for a short period of time but eventually backfires in the long run. This is not necessarily a conscious choice on our part, because we quickly internalize all kinds of rules as we acquire the ability to use language, both overtly (speaking) and covertly (thinking). In fact, most of these socially trained rules are incredibly resistant to change, even when following them leads to disastrous results.

To implement a flexible stance in the presence of challenging life moments requires that you be able to step back from mental rules, see them as rules, and not allow them to dictate your behavior. Then, and only then, will you be in a position to choose the problem-solving strategies that are most likely to work. A favorite analogy we use with depressed clients is this: if life stressors and daily hassles are the match, then following socially instilled rules that encourage emotional and behavioral avoidance is the gasoline.

In this chapter, we give you the opportunity to examine the risk situations you are facing in your life right now, and then to examine and better understand the forces inside of you that might tempt you to avoid dealing with them. To transcend depression, it’s important to practice skills that let you quickly identify and bypass strategies that promise short-term relief but guarantee long-term grief.

It is not at all uncommon for people to experience distressing symptoms in reponse to big life events or to the impact of smaller daily stresses. A term often used for these short-term symptoms is dysphoria. Nearly everyone goes through periods of dysphoria in response to something challenging in life.

It is what you do when you get dysphoric that is all important in determining the direction in which your mood will go. One common knee-jerk response is to follow the emotional avoidance rule. This will lead you to focus your energy on controlling or eliminating painful thoughts, feelings, memories, or physical symptoms. However, a cornerstone of the ACT approach is to recognize that you cannot control or eliminate painful experiences simply by avoiding them or pretending they aren’t there. They not only don’t go away, but they come back with a vengeance! And as you keep failing in your quest for control, you gradually slip into the numbness of depression. This state of emotional numbness is the only place left to retreat to when you’ve exhausted your brain’s finite resources.

An alternative way to respond to emotional distress is to “suit up and show up.” This way involves getting yourself up and “back into the game,” doing what matters to you in life. You could say that this is an approach-oriented problem-solving strategy. You feel what is there to be felt, and you do what matters to you in that same moment. The goal is no longer to control or get rid of your feelings; instead it is to use your feelings as a guide to discover what matters to you. The reason you are feeling emotional pain is not because you are broken or defective, but because there is something that matters to you in this situation. If you are willing to go for what matters to you, your pain can be your ally rather than your enemy. Of course, this is easier said than done. Indeed, the “suit up and show up” way of responding requires a significant amount of skill in mindfully accepting distressing and unwanted private events, and acting in a way that is consistent with your personal values. But it is the way a vulnerable human can transcend depression!

The first step is to simply notice that you are at a choice point, or a fork in the road, where what you do next will be a major factor in determining how you feel in the long run. Some choice points will be big, like the loss of a job, a breakup with a partner, being a victim of crime or abuse, the death of a loved one, or the loss of a home to foreclosure. Other choice points are more insidious because they are smaller and happen often. We call these daily hassles and, as the name suggests, they are the little annoyances that keep popping up in daily life: burned toast, a child’s temper tantrum, the snide remark from a coworker, the forgotten lunch, an overdraft notice, and the flat tire that makes you late for an appointment.

Daily hassles can grind us down, particularly if we try to continually avoid or suppress our emotional reactions to them. Taking the “soldier on” approach can result in unexpected consequences, such as increased irritability and a higher level of emotional reactivity in general. It can also lead to a growing sense of numbness and withdrawal from immediate experiences. Both of these consequences can exert a toll on our personal relationships and our problem-solving abilities as well. Let’s look at three common life events that offer important choice points: loss, traumatic stress, and health problems.

Sometimes it is a bitter disappointment in a relationship that launches a person into depression. Let’s look at how this happened to Bob, in order to understand how easily one can make the wrong turn in life.

Bob’s Story

Bob, a forty-seven-year-old physician, first experienced symptoms of depression while in medical school. His training was rigorous, and he often went long periods without adequate sleep. He managed to pass his classes but began to lose his enthusiasm for medicine. Although he had reservations, he went ahead with a plan to marry his long-term girlfriend after graduation from medical school. His wife was a very positive person and loved him a great deal, so life seemed better for several years. Bob graduated from his residency program and then joined a practice in a small town. He was committed to serving patients in a rural area, where there were fewer medical resources. He didn’t anticipate that this commitment would have him working longer hours than ever.

He and his wife had two children, and she often complained about his seeming lack of interest in improving their marriage. Bob felt defensive and that there was no way to win, and so he withdrew from her and the children. He took to drinking wine in the evenings because he felt more relaxed. At first, the wine seemed to give him a little energy for talking with his wife and playing with his kids. But then it just seemed to make it hard for him to focus, so he turned to watching sports on TV nonstop.

It took all of his focus just to get up and go to work and make it through the day. Bob was actually surprised when his wife left and took their children to live with her parents in a nearby city. A few months later, a colleague expressed concern, telling him, “You’re not yourself. You look tired and maybe hungover. Maybe you should see someone.” This put Bob at a choice point, and this time he made a different choice—he sought help for his problems.

Life is full of challenges, and experiences of traumatic events starting in childhood add up and increase human vulnerability to depression. One large study looked at how adverse events in childhood—parental divorce, domestic violence in the home, physical abuse, emotional abuse, sexual abuse, substance abuse by a parent, incarceration of a parent, and mental illness of a parent, among others—impacted mental and physical health in the adult years. (Felliti et al. 1998; Dong et al. 2004). The authors were surprised by how common these events were for people and by the fact that most people had never received any help in coping with them. Anna’s story provides an example of how difficult it can be to survive the emotional aftereffects of trauma.

Anna’s Story

Anna was the first person in her family to go to college. She was bright and hardworking, and completed her undergraduate studies in three years by going to school during the summers. Her childhood and teen years had been tough: Her parents divorced when she was a child, and her mother died when she was ten. When she was a teenager, her grandfather was murdered, and during her freshman year in college, she was a victim of date rape. Graduate school was an opportunity to get herself into a new setting with more career opportunities, so she enrolled without taking even a short break.

Anna wanted to have friends, but she felt so different from other people her age. And her time for socializing was limited. She told no one about her troubled history and sensed that all of the bad stuff was somehow her fault. She worked hard in her graduate classes, took extra hours at her job in child welfare, and sent money to her father, who was disabled from a work injury. At night, she surfed the Internet, watched horror movies, and played online video games until she was so exhausted that she fell asleep at her desk. Anna’s sleep was disturbed by nightmares. And when she woke up, she felt pain in her chest, which she worried about. Also, tension in her shoulders and neck annoyed her throughout the day.

Over time, she found it hard to concentrate on her studies and began to skip lectures and an occasional exam. Anna’s grades dropped, and her major professor called her in for a conference. This put Anna at a choice point, and she chose to do something proactive about her growing symptoms of depression. She decided to read a self-help book recommended by her professor and promised that she would see a counselor at Student Health Services in a month if she wasn’t feeling better.

Another common pathway into depression involves falling into patterns of behavior that lead to poor health. A common misconception in our culture is that health comes naturally, that there is no real need to work to preserve it, and that doctors can find ways to eliminate health problems when they do occur.

Actually, it is behavioral and social factors that are the heavy hitters in health outcomes, rather than access to medical treatment. It is the hard stuff—eating well, exercising, getting restful sleep, and cultivating good relationships—that helps us feel good physically and mentally. Engaging in unhealthy behaviors is a common way to avoid or control distressing emotions, and Joe’s story illustrates the long term cost of using this strategy.

Joe’s Story

Joe had always struggled with the feeling that he didn’t fit in with his peers, that he was an oddball. When Joe was in social situations during his teen years, he would play with his phone or hang out at the food table until he could make an excuse to leave. Joe liked cooking and considered himself a “foodie,” so a pattern of eating to avoid his feelings spread to other contexts in his life, such as when he was studying, playing video games, or feeling lonely.

By the time he enrolled in college, he weighed more than three hundred pounds. In his senior year, he met a delightful woman and lost quite a bit of weight to please her. They married, and within the first year of their marriage he gained all the weight back plus some. His wife was critical of his weight and his eating habits, particularly his eating ice cream out of the carton at night after dinner. Eventually, she had an affair, and Joe fought off devastating feelings of rejection by moving to a separate bedroom, snacking, and listening to music in his room at night.

When his doctor diagnosed high blood pressure and high cholesterol, Joe felt even worse about himself. He made excuses for not attending church and avoided family gatherings except on big holidays. He preferred to stay home, where he could watch movies, listen to music, and enjoy his favorite junk foods. Joe didn’t want to feel the pain of being rejected by his wife, and he didn’t want to hear any more bad news from his doctor. He didn’t want to have the worries he had about his body, which seemed to be failing him.

Late one night, Joe experienced severe chest pain, and his wife took him to the emergency room. He was diagnosed with angina and told to lose weight and change his eating habits or he might end up suffering a heart attack. That day Joe found himself at a choice point. The next day he told his wife that he needed to see a therapist to help him turn his life around.

Bob, Anna, and Joe each avoided painful personal problems in order to function—until they realized that their solutions did not help them function, at least not in ways that really mattered to them. Their values regarding health, relationships, work, and play were alive and well, but their behaviors were driven by avoidance rather than passion. As is typical with most people who suffer from symptoms of depression, all three made a decision to seek professional assistance to improve their lives. With help, they learned to use many of the skills we teach in this book. They learned how to turn around and face their depression one small peak at a time.

Remember the old saying, An ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure? This saying speaks volumes about how depressions get started as well as how to get out of them. As we mentioned earlier, stressful life situations can act as triggers for depression or, if allowed to fester, can create chronic depression. These risky situations can be found in any domain of your life: your relationships, work/study, leisure/play, and health. There is no benefit in trying to ignore these risky situations, hoping they won’t materialize or that they will somehow get resolved on their own. If you find yourself taking that approach, it might be a signal that you are unknowingly following the emotional avoidance rule. A far more productive approach is to look these problems squarely in the eye so that they don’t sneak up on you.

Identify Your Depression Triggers

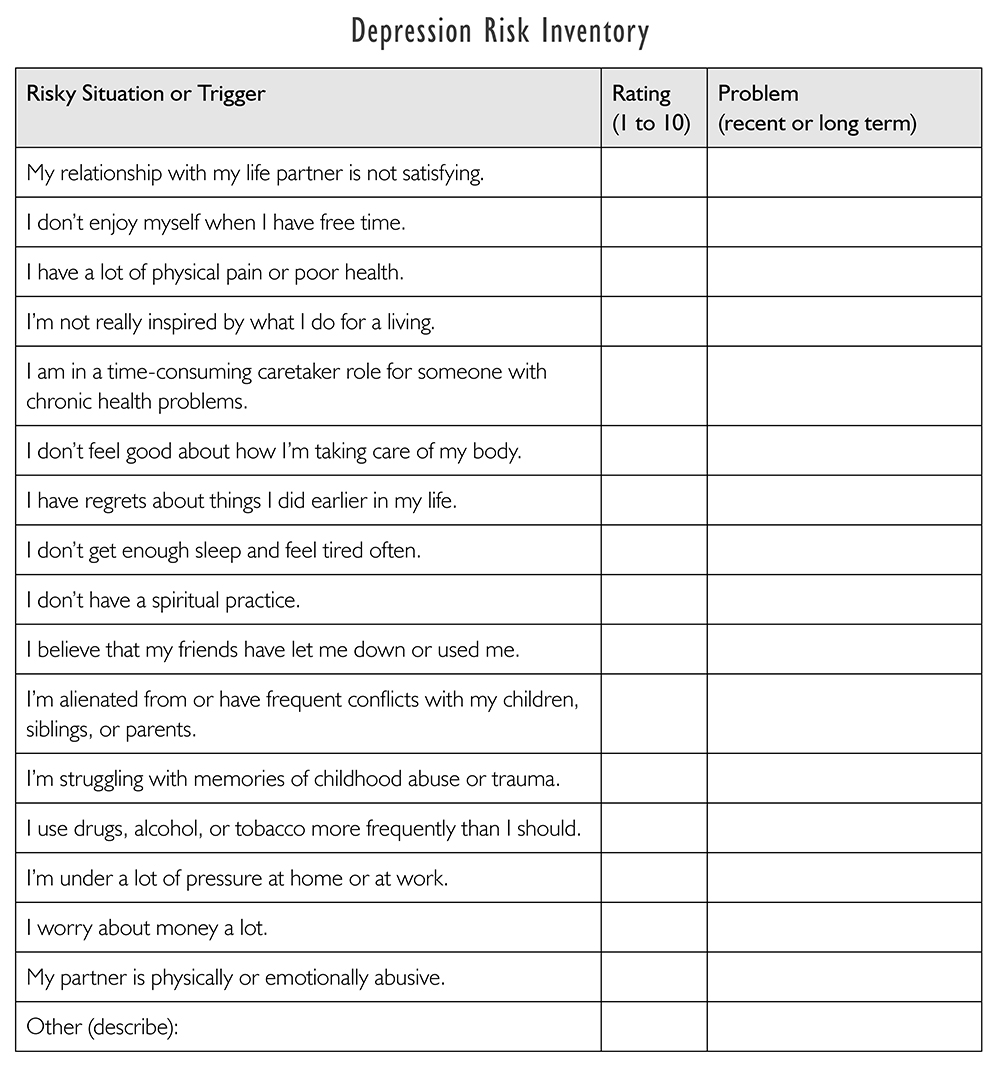

To help you better understand the smoldering problems that might increase your vulnerability, read through the list of depression-risk situations below, and for any that might apply to you, rate how big of a problem it is on a scale of 1 to 10, whereby 1 is not a big problem at all and 10 is an extremely big problem. In the right-hand column, indicate whether the risky situation has developed recently or has been around for a long time.

Further Exploration. What did you discover as you completed this risk assessment? Did you mark a lot of areas or just one or two? How much emotional turmoil does each risk factor cause? Some of these problems might be chronic or long-standing issues, and others may have surfaced only recently. Here are two basic rules of thumb for calculating your level of depression risk:

- The more problems you have that create painful feelings for you, the greater your risk.

- The longer these problems have festered in your life, the greater your risk.

Most depressed people don’t deliberately avoid dealing with their pressing problems. At some level, they know that avoiding personal problems doesn’t help their situation and that tiptoeing around painful thoughts, feelings, or memories doesn’t solve anything. So why is it that intelligent, insightful people can know in their hearts and minds that a particular strategy isn’t helping, but still use it anyway?

It all comes down to the two toxic processes we mentioned in chapter 1: rule following and avoidance behavior. Together, they form a powerful one-two punch that makes it very hard for people to get out of the harmful cycle of avoidance that feeds depression.

If a strategy is systematically making a depressed individual feel worse, then the commonsense solution is to stop using it and look for something else that might work better. But this usually doesn’t happen in depression—or in a lot of other situations that cause suffering. There must be some mental process that is overriding a depressed person’s ability to objectively assess the results of ineffective strategies and then make needed changes in the approach. Right? The culprit appears to be the very makeup of the mind itself, which makes us insensitive to the direct results of our behaviors, particularly those behaviors that are under the influence of rule following.

We’ll try not to be too abstract about this, but we’d like to share a bit of science to help you understand how language and thought actually create what we affectionately call the “mind” and how the mind, in turn, controls our behavior. This is a little tricky because most of us aren’t used to looking at our mind as a scientific oddity; rather, we’re used to being our mind and doing what it says. Let’s start by delving into a relatively new approach to human language called relational frame theory (RFT; Hayes, Barnes-Holmes, and Roche 2001). RFT has had a huge impact on the development of ACT; indeed, many ACT interventions are based on the principles of RFT.

The basic goals of RFT are to discover how the various capabilities of human language are acquired over the life span and to decipher the complex process by which language functions to regulate our behavior. Two important functions of language are to both organize and regulate the behavior of each member of the clan. These regulatory functions are embedded in language itself, so we might not even be aware that our behavior is controlled by hidden forces within the mind.

Basic to the RFT approach is the idea that spoken and unspoken language (what we know as thought) are essentially the same thing. They are symbolic activities that allow us to both express ourselves to others and silently reason within ourselves. As far as we know, humans are the only species that have this capacity, which is sometimes referred to as self-reflexivity. This means that we can engage in internal dialogues with our minds. This is a terrifically useful evolutionary development and is clearly the reason we are at the top of the food chain, but there is also a dark side to this fantastic ability. When it is turned inward and applied in the wrong way, it can produce enormous suffering. While we are at the top of the evolutionary pyramid, humans are also the only species known to commit suicide. For present purposes, we want to zero in on how it is that language can invisibly move us in the wrong direction when it comes to making contact with, understanding, and utilizing our emotional experience.

In RFT, the term rule-governed behavior is used to describe behavior that’s under the direct control of arbitrarily derived symbolic relations. (That term is a mouthful for anyone. Try to say it twenty times really fast if you dare!) Arbitrarily derived relations allow us to form mental rules about how to behave without actually coming into direct contact with the consequence the rule refers to. Their evolutionary importance cannot be overstated. If you think of language as the operating system that has put us at the top of the food chain, then think of rule-governed behavior as the main cog of that system. We can teach children hundreds if not thousands of important facts about life just by giving them a mental rule. This means the child doesn’t have to learn the rule via firsthand experience. For example, a mother tells her child, “Never, never touch the burner on the stove when it is hot or you’ll hurt yourself!” The child doesn’t have to go over to the stove and learn this simple, painful truth by putting his or her hand on the burner. Rule-governed behavior is such a powerful way to transmit knowledge that this is the dominant way that human knowledge is being advanced.

Rule governance also extends to the organization of social and cooperative behaviors. Many of these socially oriented rules also contain a promised reward for compliance, for example, “Smile and the world will smile with you, cry and you cry alone.” If the rule says, “Feeling sad is unhealthy for you, and when you get rid of being sad you will be healthy again,” following that rule will be more important than being aware of whether the rule actually works in real life. This is a basic principle of RFT known as augmentation. An augmental promises additional rewards for following the programmed rule (for example, if you just get rid of your sadness, then you will live a healthy and happy life).

Augmentation is such a potent form of behavioral control that it pretty much overwhelms our ability to change behaviors based upon the actual results of following the rule. This means that once a rule is established in your language system, it will continue to be followed even if the objective results of doing so are dismal. Sound familiar? You’ve probably been in life situations in which you used the same strategies over and over without much in the way of results. Maybe you argued repeatedly with a spouse, partner, child, or parent about the same basic issue with no sign of progress. Or you snacked on some junk food at night to help you chill out even though it leads to heartburn and difficulties with sleeping later.

In order to exert their regulatory influence on behavior, you have to buy rules and then follow them—sometimes consciously but often without awareness that you are doing so. Buying a rule means that you attach to it and allow it to direct your behavior. For example, let’s imagine that it’s your birthday and your partner hasn’t said anything about cooking a special dinner or taking you out to dinner. You might run into a rule such as, “If my partner really loved me, I shouldn’t have to even mention that it’s my birthday and that I’d like to do something special.” This rule encourages you to keep quiet and see if your partner shows you the behavior that demonstrates love and caring. Because most rules actually originate within language, we have a hard time seeing them for what they are, and so most of the time we are not conscious that the rule is controlling our actions. In ACT, the term used to describe this process of overidentifying with rules is fusion. Like the term implies, fusion involves melding yourself within your experience in the moment, such that you lose the distinction between yourself and what you are experiencing. In a fused state, people become very susceptible to rule following.

For example, it isn’t unusual for a depressed person to think something like, “I know drinking is only going to make my depression worse” on the way home from work. Once at home, this same person may think, “I feel angry, my life is going nowhere, and I can’t allow myself to feel this way. The only way I’m going to feel better is to have a drink.” Minutes after recognizing, again, that drinking will only worsen the problem of depression, this person may attach to other rules that propel him to drink to excess. These rules suggest that to feel healthy he must immediately eliminate “bad” feelings, such as anger and emptiness, and “bad” thoughts, like “My life isn’t going anywhere.” Unfortunately, the solution of drinking leads to more depression in the long run.

The tricky thing about fusion and rule following is that they are both essential to our ability to operate in a social context. You don’t want to be questioning your mind when it gives you a rule not to enter the crosswalk when the stoplight is red. When you hold hands with someone you love and say, “I love you,” you don’t want to be thinking that “I love you” is just a thought. You want to fuse with that thought and experience the full force of your intimacy in the moment.

So the real challenge you will face in your quest to transcend depression is learning when it pays to fuse with and follow rules, and when it is destructive to do so. The first step in this process is to simply become aware that there is a distinction between you and your thoughts, feelings, memories, and physical sensations. You are not the same as your experiences. Think about your relationship to your thoughts, emotions, and memories like this: If you have a thought or emotion, you can be the owner of it or you can be owned by it. When you’re the owner, you would say something like, “I’m having the thought that life is pointless” or “I’m aware of feeling sad right now.” The ability to simply be aware of thoughts, feelings, or memories—without buying into them—is a cornerstone of mindfulness.

Nowhere is the impact of rule following more evident than in the steady stream of automatic, habitual behaviors that have come to characterize modern life. We have exchanged intentional living for a life organized by social rules that require us to perform activities that have little or no connection to our values. If you think about your current daily activities (brushing your teeth, commuting to work or school, eating a meal, interacting with your partner), how much of the time are you aware of being in the moment and being intentional in your actions? If you’re like most people, the answer will be, “Not very much of the time.” In ACT, we call this living on autopilot. We tend to go through the motions of daily life with limited awareness and intentionality.

For years, it has been an accepted scientific fact that as little as 5 percent of our behavior is intentional and purposeful. The other 95 percent of the time, our behavior is controlled by environmental cues (alarm clocks, text notifications, calendar alerts) and social cues (doing what others are doing, dressing to imitate others; Baumeister et al. 1998). Neuroscience studies have demonstrated that we are hardwired to observe, integrate, and copy the behavior of others (Gazzola and Keysers 2009). The brain’s architecture is designed to help us do the same thing as other members of the tribe.

To make matters worse, neuroscience research shows that we do things automatically as part of the brain’s attempt to protect problem-solving and attention resources. So, to a limited extent, automatic behavior serves a protective function. There are literally hundreds, if not thousands, of activities that we must perform every day just to be human. Research shows that when you pass a certain threshold of doing activities on only a voluntary basis, you’ll quickly have trouble maintaining the same level of intention and awareness from moment to moment (Galliet et al. 2007).

From the ACT perspective, being on autopilot isn’t the problem; it is being on autopilot most all of the time that is dangerous. Extended time spent on autopilot allows rule-governed behaviors to occupy areas of life where rules don’t work very well. Particularly if you are depressed, one likely result of a lot of time on autopilot is that you will habitually engage in a steady succession of small-scale emotional and behavioral avoidance behaviors. In this sense, daily challenges of living can function somewhat like the ancient Chinese practice of water torture: One drop of water on your head doesn’t seem like much until you’ve spent days experiencing one drop of water at a time. One little act of emotional avoidance doesn’t seem like a big deal, but what’s to stop it from becoming a hundred?

Rule following is rule following, and unless you consciously break the pattern of avoidance by getting present and intentional, your vulnerability to depression can quickly get out of hand. To develop resistance to autopilot rule following in everyday life, it’s important for you to develop a reliable set of go-to strategies that help you get present and intentional. And the first step in doing that is to look at your vulnerabilities toward running on autopilot. Those areas will tend to reflect the rules you’re following. The exercise that follows will help you do just that.

Inventory of Automatic Living

The following survey will help you identify tendencies toward automatic living in your current lifestyle. Read each item and circle an item number if it applies to you.

- I feel bored much of the time.

- I spend a lot of time watching TV or surfing the Internet.

- I have trouble doing things at a slower pace than what I’m used to.

- I’m always looking ahead and planning ahead.

- I like to zone out when I have free time.

- I often feel disconnected from my body’s senses.

- I often notice that I’m not paying attention to what I’m doing.

- I often forget to stop and take relaxation breaks during the day.

- I find it difficult to relax even when I have free time.

- I prefer activities that distract me when I have free time.

- I have trouble following through on tasks that require close attention.

- I feel numb inside much of the time.

- I feel rushed and like I’m always running behind.

- I notice that I stop paying attention when I’m talking with someone.

- I have trouble spending quality time with my partner or children.

- I tend to see my day as full of duties to perform.

- I tend to put off doing activities that I might enjoy.

- I get irritated if my daily routine is interrupted.

- I don’t like to sit still and will try to keep myself busy.

- I feel like I’m not cut out to relax and chill out.

Further Exploration. Now take a minute to notice the statements that you circled. These are the daily experiences that contribute to autopilot behavior and that may set you up for depression. Now that you’ve identified them, you can work toward creating a more mindful and meaningful lifestyle. You can get there by daily engaging in specific new practices, which you’ll learn in part 2.

Many behaviors that are typically associated with depression—such as isolating at home; daydreaming; sleeping a lot; avoiding social interactions with a spouse, children, or friends; watching excessive TV; texting or being on social media for hours on end; and mindlessly surfing the Internet often—are better thought of as avoidance behaviors. Some of them keep us out of touch with unpleasant emotions; others steers us away from life situations, events, or interactions that are likely to trigger painful experiences inside.

While many of these behaviors may temporarily buffer depressed individuals from painful private experiences, in the long run they generate more depression. This is because when you disengage from people and the other things that matter to you, you also remove the potential rewards that might be waiting for you in those same activities. Thus, habitually engaging in emotional and behavioral avoidance behaviors can put you into a vicious downward spiral that is very hard to get out of. Because of this, it is very important that you identify both current and potential patterns of emotional and behavioral avoidance in your life.

What if it is impossible to gain control over thoughts, feelings, memories, or physical symptoms simply by willing them away? What if the end result of avoidance strategies is that you actually have more distressing, unwanted private experiences, not less? Let’s examine these two powerful ideas in more detail.

As far as we know, it’s impossible to prevent emotions, thoughts, memories, and sensations from occurring in the first place. They are part of your learning as a human being. And the nervous system doesn’t work by subtraction. This means you can’t unlearn thoughts, feelings, or memories once they’re stored in your experience. They can show up at any time, in any situation, and you have no say as to when, where, and how they will make an appearance. Your thoughts, emotions, memories, and physical responses are historically learned and are conditioned to appear whenever a situation triggers them. You can’t keep a memory from making an appearance. You can’t prevent an emotional reaction from showing up. You can’t prevent yourself from thinking an unpleasant thought. The grand illusion contained in the emotional avoidance rule is that we somehow possess these abilities, when in fact we don’t.

Suppression, a common form of avoidance, is the conscious attempt to squash a private experience out of awareness. Here is a little exercise to show why suppression doesn’t work. Try this for a moment: Think of a campfire. Imagine the flames, smell the burning wood, and feel the warmth of the air. Now stop. Stop having this image or memory, stop smelling the smoke, and stop the perception of warmth. Stop them completely. You are not to think of any of this from this moment on. What happens when you prohibit yourself from thinking about the campfire?

Now let’s try something different. Think back to being in school, and recall something unkind that a teacher said or did to you. How old were you at the time? What were your teacher’s exact words and tone of voice? Try to recall the room, your teacher’s appearance, and all the other aspects of the experience in as much detail as possible. Now stop thinking about this unpleasant experience. Put all thoughts, memories, and feelings about it completely out of your mind.

How did you do? If you found the image of the campfire or your memories of your teacher’s unkindness hard to get rid of, you are by no means alone. Research shows us that conscious attempts to suppress or avoid our private experiences will actually increase their intensity. This holds true not only for unpleasant thoughts or memories (Marcks and Woods 2005) but also for negative feelings (Campbell-Sills et al. 2006). So if you try to suppress an emotion, memory, or thought that you don’t like, it will just come back to you in spades. It’s another paradox: You can’t control which private experiences show up, but you can make them much worse by trying to suppress them.

Inventory of Emotional and Behavioral Avoidance

Pick a recent life situation, event, or interaction that didn’t go well and left you feeling even more depressed. Take your time to write a few sentences about the situation. Then write down four specific actions you took in that situation. Finally, analyze what function that behavior might have had.

Situation:________________________________________

__________________________________________________

__________________________________________________

Action 1:_________________________________________

Action 2:_________________________________________

Action 3:_________________________________________

Action 4:_________________________________________

Now, look at the function of the actions you took. Did one or more of your actions serve one of the following purposes?

- Avoiding the situation or interaction that might trigger emotional pain

- Treating unpleasant emotions, thoughts, or memories as threats to my well-being

- Distracting myself from negative emotions

- Numbing myself to negative feelings

- Trying to control my emotions in order to not feel worse

Further Exploration. Did you identify one or more actions that involved rule following and avoidance in an effort to control your feelings? We all do this to some extent. However, we can come to rely too much on these strategies. Once you begin to understand how rule following and avoidance work, you can anticipate and look for the situations, events, or interactions that tend to trigger those responses in you and practice “just noticing” the urge to follow the rule or avoid the situation.

From the ACT perspective, the way through depression involves learning to pay attention to the patterns of rule following and avoidance that can end up fueling your depression, rather than helping you feel better. Depression is essentially a signal that you are having a difficult time detecting and accepting your emotions, and making choices that help you pursue the life you want. If you think of it this way, you will realize that learning to deal with your depression is more of a means to an end than an end itself. The end we have in mind is helping you create a life worth living, one in which you are doing life-enhancing things that support your values.

This guided exercise offers a glimpse of what you’d be doing right now if your depression was no longer a barrier to you having a better future. Sit down in a comfortable position, close your eyes, and take several long deep breaths.

See if you can focus on where your life is right now—the things in life you feel good about as well as things that are causing you to suffer. Now, imagine that your depression miraculously disappeared overnight and is no longer a factor in your life. Because this miracle happened while you were sleeping, you don’t actually know what made your depression disappear. All you know is that you are now free to choose to do the things in life that really matter to you.

First, imagine what steps you would take to protect and improve your health. This might involve cutting back on your use of chemicals or improving your diet or exercising more. It can be anything that comes to mind.

Next, imagine what you would like to do to improve the number or quality of your social connections and close relationships, be it through working to grow your relationship with your life partner, children, friends, or siblings, or being more involved at the community or volunteer level. Just let whatever comes to mind show up without evaluation.

Now think about what would matter to you in your work, career, or education pursuits. Just see if there is some action that you would like to take to move yourself forward in this area of life.

Finally, think about how you would like to spend your leisure time—the time when you get to play in life. What would playing look like for you? It might involve improving yourself as a spiritual being or challenging yourself with a new hobby or pastime. Just see what shows up when you let yourself imagine a better future in this area of life.

And now, just allow yourself to savor the moment of having a better future ahead of you. Breathe into that better future. See it as a distinct possibility for you. And, when you are ready, come back into the moment and take some time to complete the written portion of this exercise.

A Better Future for Me…

For each of the areas listed below, write one important thing you would be doing if the barrier of depression evaporated while you slept.

In my pursuit of personal health (including exercise, spirituality, diet, and alcohol or drug use), I would

___________________________________________________

In my relationships (partner, family members, friends), I would _______________.

In my work activities (including as a homemaker, volunteer, or student), I would _______________.

In my leisure life (including play, hobbies, recreation, creative pursuits), I would _______________.

Further Exploration. Don’t worry. We aren’t going to ask you to do all of these things—just yet. For now, just pat yourself on the back for being willing to imagine! Whenever you return to this list, think about your progress and whether you’re getting closer to realizing any of these visions for your life. If you start to address emotionally difficult personal issues and situations, you can radically transform your life. It takes commitment, time, practice, and accepting that you won’t always feel good. But we guarantee you that this is something you can do!

- The life events, situations, and interactions that can trigger depression are as numerous and varied as the people who experience depression.

- Small, repeated daily life hassles can be as depressing as big life events.

- Rule following involves having your behavior regulated by social rules that are hidden in your language system.

- A habitual pattern of living on autopilot can set you up for depression, because it makes you prone to rule following.

- Emotional avoidance is a particularly toxic form of rule following that involves refusing to make direct contact with distressing thoughts, feelings, memories, or physical sensations.

- Behavioral avoidance involves steering away from life situations that might trigger painful emotions.

- Learning to recognize patterns of avoidance in your life is a big step forward in your quest to transcend depression.

- Acceptance and mindfulness skills will allow you to approach distressing private experiences with an attitude of openness and curiosity.