It’s All About Workability

It is a risk to love. What if it doesn’t work out? Ah, but what if it does?

—Unknown

As we have mentioned, we don’t want you to think of depression as a problem to be solved as much as a signal that something in your life is not working. That aspect of your life that is not working is the problem that needs to be solved. And it’s not getting rid of your depression that’s going to do it; it’s finding those things that aren’t working and fixing them that will. And you can’t do that very well if you are preoccupied with trying to control your depression or the other feelings that lurk close by.

Chances are, if you are going through this self-help program, you are already knee-high in at least one challenging life situation. To achieve lasting change, you must first be brutally honest with yourself and take inventory of where you are right now. This can be really difficult—it can feel uncomfortable, even scary—but it is a healthy and essential move toward healing. As we like to say: Start from where you are, not from where you’d like to be!

At the end of the previous chapter, we dared you to imagine a better future, a life in which you are able to do what really matters to you in four key areas of living: relationships, work/study, leisure/play, and health. In this chapter, we will help you take stock of how your life is actually working in those same areas of living. We are not doing this to bum you out. We want you to keep that image of a better future in mind as you examine the strategies you are currently using to move your life forward.

As we help you go through this personal inventory, you will learn about workability, a key ACT strategy that you can use to short-circuit rule following. Remember: Most of the avoidance rules you follow are also being followed by other people, and this makes it even more difficult to walk away from these rules. Indeed, avoidance might even seem sensible on some level. But if what the emotional avoidance rule promises (freedom from emotional pain, resulting in health and happiness) could actually materialize, we wouldn’t be having this discussion. Because therein lies the rub: Following the rule, no matter what its promises are, doesn’t actually deliver the goods!

To see through rules, you not only have to be aware that they are there but also understand what they are promising. Workability helps you analyze whether your methods of responding to your depression are actually working. The rule you are heeding promises positive results if you just follow it. The questions you must answer include: Are these strategies working to promote my best interests in life? Or are they driving me deeper into depression?

In this chapter we’ll also look at possible depression risk factors in your life right now, along with ones that might appear in the immediate future. Finally, we will work with you to identify life domains where you can try intentional, mindful strategies that are likely to produce better results.

Keep in mind that “Health is a state characterized by anatomical, physiological, and psychological integrity; ability to perform personally valued family, work, and community roles; ability to deal with physical, biological, psychological, and social stress; a feeling of well-being; and freedom from the risk of disease and untimely death” (Last 1988, 57). We like this definition because it acknowledges that health isn’t simply a physical state; it’s also a psychological and social state. This definition also suggests that health is a dynamic relationship between positive coping and stress-inducing behaviors. Simply put, either your behaviors can restore you and buffer you from depression, or they can tear you down and make you more vulnerable to depression.

In keeping with the philosophy that depression is not something you have but is something you do, we want you to begin taking a closer look at vitality-producing and depression-producing behaviors in the four main domains of life. The exercise that follows provides an opportunity for you to evaluate behaviors in each major life domain.

Behavioral Risk and Vitality Assessment

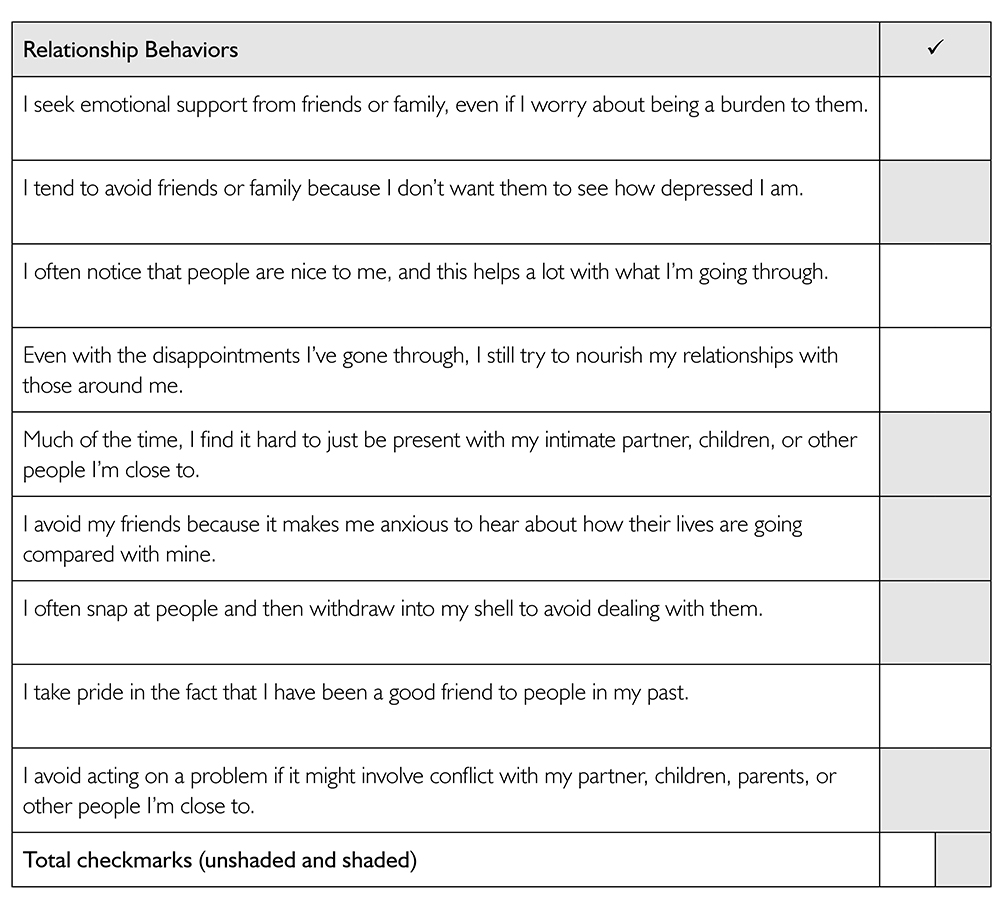

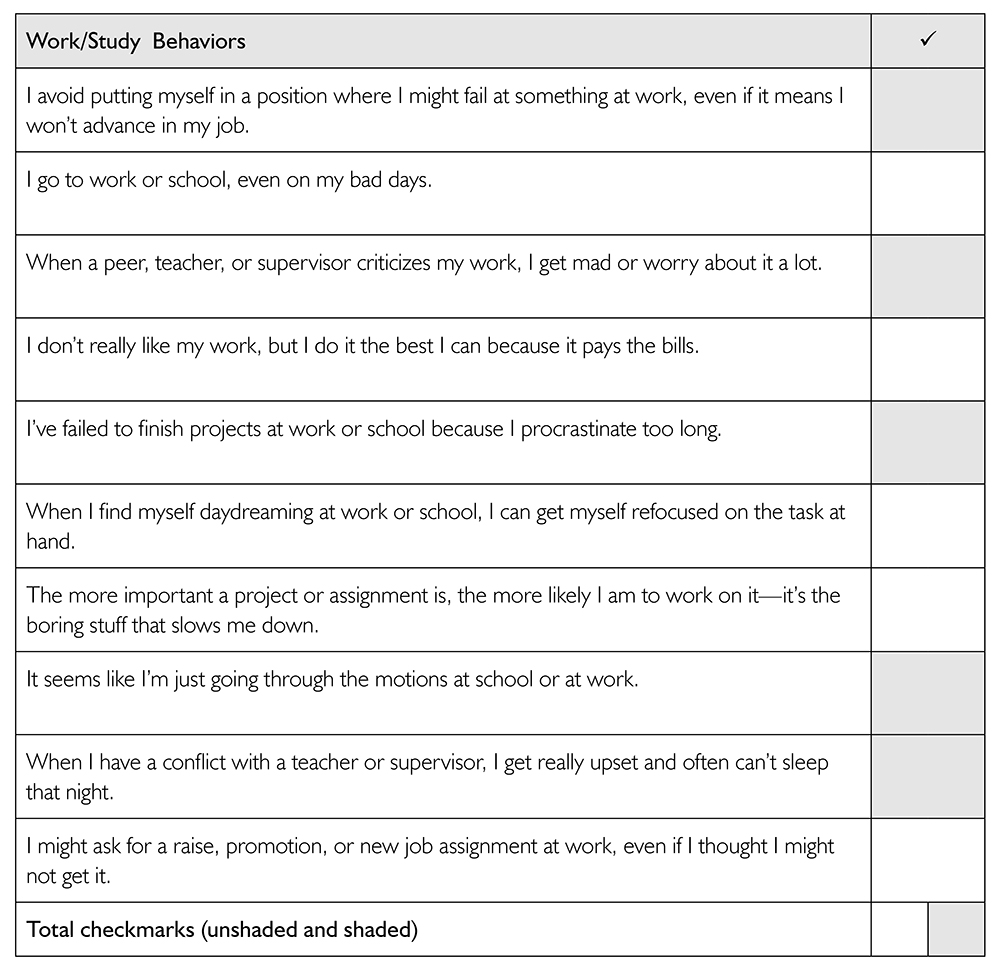

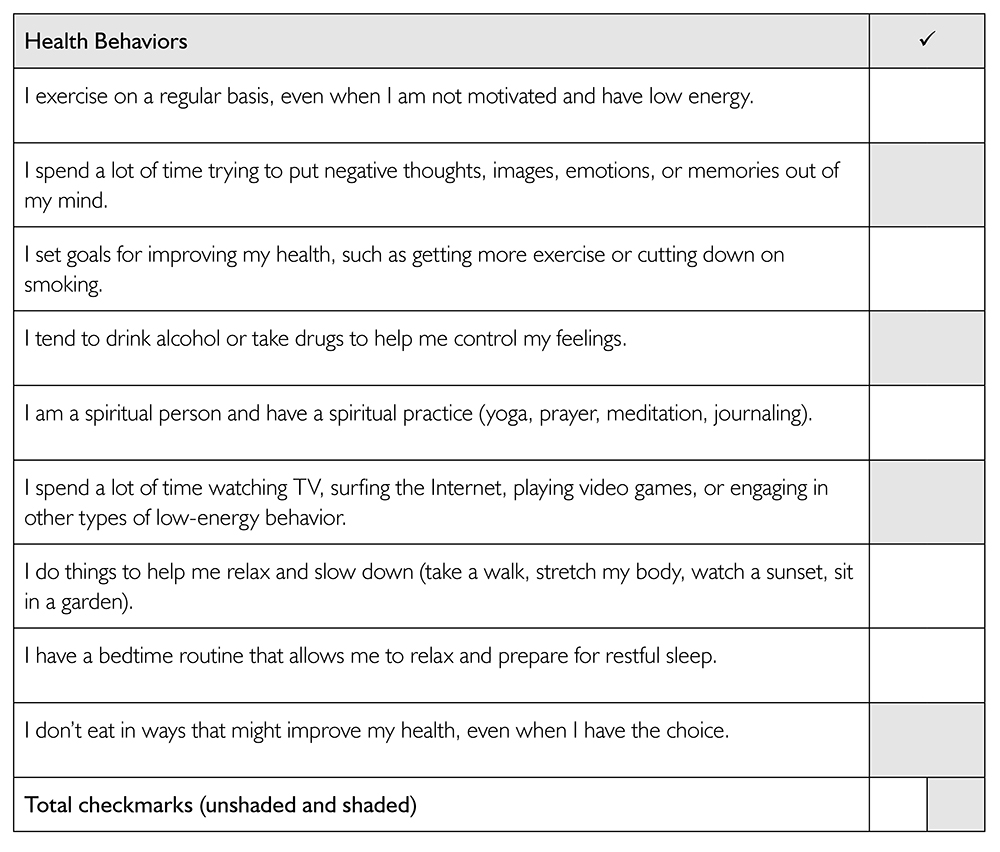

Use the following four worksheets to reflect on your behavior patterns as they relate to the fundamentally important life domains of relationships, work/study, leisure/play, and health.

Read through each statement and place a checkmark next to those that ring true for you most of the time. At the end of each worksheet, count the number of checkmarks placed in both shaded and unshaded boxes, and record the totals. Note that there are no right or wrong answers. These surveys are designed to provide you with a baseline for your experience. Later, say a month from now, you can repeat this assessment and check your progress.

Further Exploration. Now let’s look at your scores. Did you check more shaded than unshaded boxes? If so, it’s probably not going to surprise you that the shaded boxes represent behaviors that might put you at an elevated risk for depression, whereas the unshaded boxes represent behaviors that could produce a sense of vitality and reduce or counterbalance your risk. As we said, there are no right or wrong answers, and we all have an assortment of coping behaviors that we apply across varying life situations.

Did you identify some vitality behaviors? If so, great—keep them going. Perhaps you found some vitality behaviors that you have done in the past—or might like to try in the future. Keep these in mind to explore later; the goal is to find workable solutions.

What did you learn about your risk behaviors? Did you endorse more risk behaviors in one life domain than in others? Did any of the risk behaviors you endorsed surprise you? Remember that the purpose of taking a fearless inventory is to get your feet on the ground and see things accurately. It is neither good nor bad. It just is. In preparing for radical change, you first have to know where you are starting from before you can form a plan for getting to where you would like to be.

Workability is a central concept in the ACT approach. It conditions how you look at your behavioral options in life. The goal of course is to use behaviors that promote the kind of life you would like to live. The reference point is just as important as applying the workability test, because you can only assess how something is working by being clear about what “working” would look like. This is why we invited you to dare to imagine a better future at the end of chapter 2. That future is your reference point. You gauge the workability of any particular life strategy you are using in terms of whether it is moving you toward that reference point. If the strategy is moving you in the direction of a better future, then it is working; if the strategy is moving you away from the life you want to live, then it is not working.

Another benefit of workability is that it shifts your focus to the actual results of your actions, not what you think should happen. For example, if you decide that you will feel better if you stay home and don’t hang out with your friends, because then you won’t be a burden on them, test it out! Did you actually feel better in the end? Or did you feel worse? Using the workability yardstick calls out your rule following behaviors and puts the rule to a test by an interested party: you. The goal is to determine whether following the rule produces the results that are promised in the rule. In other words: It isn’t about what SHOULD work; it is about what IS working and what isn’t!

Les’s Story

Les is a forty-nine-year-old divorced mailman who loves dogs. He hoped to own a dog, but he put this plan on hold in order to focus on his other work and family obligations. He not only worked full-time and took on extra shifts to help pay for his kids’ college tuitions, he also cared for his mother, who struggled with advancing dementia.

For many years, he would pause on his mail route to watch someone with a dog, and he’d imagine that he had one too. Then he made himself stop looking because it made him feel sad, and he didn’t want to feel sad. He stopped talking about dogs too, because that made him sad. He even tried to pretend that he was annoyed by other people and their pets; but in his heart, he loved dogs and he still wanted one.

Over time, his work and caregiving duties increased to the point that they pretty much consumed all of his time. His mood began to decline. He secretly blamed his mother for making it impossible for him to own and care for a dog, and he became increasingly short-tempered with her. He began to turn down chances to spend time with his kids in order to preserve his declining energy for work and taking care of his mom. Pretty soon, they stopped calling to invite him out, and Les was hurt and felt that they had rejected him.

Les’s story demonstrates a core principle of workability, namely, that it is closely tied to what matters to you in life. The issue is not about whether it’s right or wrong to have a dog; it’s a matter of what Les is seeking in his specific life context and whether his strategies are workable, or helping him succeed.

When Les looked at dogs and imagined having one, he was making contact with what mattered to him—sharing his life with a dog. When Les turned away from what mattered, he began dealing with the emotional consequences through emotional and behavioral avoidance. These strategies, in turn, created problems of their own. His suppressed sadness resurfaced as irritability toward his mother. His avoidance strategies also depleted his mental energy, which resulted in him pulling away from his kids.

Workability focuses on the direct results of strategies you’re using in life. No matter how fond you are of avoiding personal pain, if doing so makes our situation materially worse, you must be willing to go in another direction and face the pain. In general, emotional and behavioral avoidance strategies can’t stand the test of workability, no matter how ingrained or automatic they may be. You are either getting the results you want in life or you’re not. And if you’re not, it’s time to try something different!

When Jill fused with this rule—“I must meet all of his needs now, when life is so hard for him”—she could not see that following it was exhausting her and robbing her of the joy she might experience in caring for her husband were her life activities more balanced among work, play, and love. Trying to address all of her husband’s needs without help from others was not producing feelings of love and closeness. Quite the contrary, it was leaving her tired, sad, hopeless, and irritable. Only when she was able to stop and see the rule was she able to realize that her actions were not working to produce the assumed results. Despite all her efforts, her good-wife behaviors were not resulting in a good-relationship experience for her husband or herself.

Jill’s Story

Let’s take the example of Jill, an older woman who struggled with negotiating the challenges of retirement when her husband became ill. Prior to retirement, Jill had a full life. Although she disliked her long commute, she liked her job. She also enjoyed reading and going to book club meetings with her friends. She also loved knitting and listening to music. She planned to do more knitting and to attend more music events after retirement, but her husband suffered a stroke shortly after her retirement, and she devoted most of her time to caring for him.

When not caring for him, Jill worried about him and distracted herself from her growing sense of disappointment and frustration by watching mindless television shows and eating comfort foods that only made her feel worse. Her husband’s health continued to decline, and she told herself she had to stay the course and be available to him around the clock. Any attempt to see friends or even do enjoyable things at home seemed to be out of the question, given the demands of the care her partner needed at this point in his life.

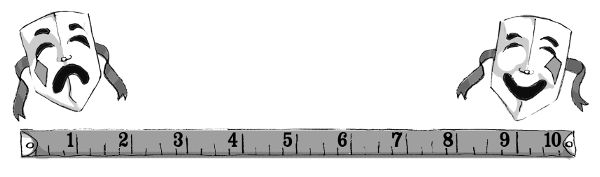

Since life is dynamic, workability in one’s life moves up and down. This is a basic truth of living a vital life. Behavior that pays off for you in one situation might result in problems in another. When life workability is high, your sense of vitality in relationships, work, and leisure pursuits is strong. This doesn’t mean you have peak life experiences every day, but it does mean that you know what’s important to you and that you are moving toward it. Remember: as hard as it may be to keep this truth in mind now, a life worth living isn’t defined by the absence of pain; rather, it’s a path on which pain is accepted and experienced in a healthy way. To keep yourself focused on workability, we recommend that you end each day by rating its workability using the yardstick below!

This exercise will help you understand from firsthand experience that workability isn’t so much about the absence of pain as it is about approaching pain in a way that produces a sense of showing up and living according to what matters.

Begin by recalling an emotionally challenging situation, event, or interaction when you showed up and did what you believed in, even while you were in pain. Describe the situation in the lines provided, then write down the actions you took that were workable.

Next, think a little deeper. What showed up in your body or mind that told you that your approach was working? Did you feel proud of yourself? Did you notice a more relaxed feeling in your body? Did you have the sense of growing as a person? Just look around in your memory of the situation and see what is there in a positive vein. Write this down as well.

Challenging event, situation, or interaction:

Workable actions I took:

Mental experiences of workability:

Bodily experiences of workability:

Further Exploration. What happened when you really immersed yourself in this workability moment? What kinds of feelings showed up? Was there a mixture of difficult feelings and more-gratifying feelings? That is often the case when we deal in a workable way with a challenging situation. Some of the painful emotions are there right along with the more rewarding ones.

Did you experience the workability of the moment anywhere in your body? Sometimes we carry a lot of physical tension into a painful situation. Then, when we engage in workable actions, the tension gives way to other bodily experiences like excitement or a sense of relaxation.

Hopefully you discovered that you don’t have to engage in avoidance to feel better. The kind of “feeling better” derived from avoidance is just the absence of pain. The rewards that come from workable responses go far deeper than that. They often involve not just the reduction of pain but, more important, the appearance of positive emotional experience, positive self-regard, and optimism.

Before we proceed with the next step of your fearless self-inventory, we want you to learn the difference between short-term coping strategies and long-term coping strategies. A lot of the risk behaviors listed in the Depression Risk and Vitality Assessment are short-term coping strategies designed to help you deal with your depression in the moment. When you are depressed, it is easy to make decisions based on how you are feeling and the rules that pop up in your mind. This often occurs with limited awareness and intention, such that you don’t realize you are at a choice point. A choice point is a moment of truth that can be small or large in scope. It involves choosing to move in the direction of your better future or in the opposite direction, toward depression. The question is: What are you going to choose at this moment in time?

If you move in the direction of avoidance, it will likely take you away from the life you would like to live, even if the impact is ever so small. As we pointed out in chapter 2, avoidance behaviors can function like Chinese water torture. Each avoidance behavior looks small in magnitude, but when you add them up, they have the power of a freight train.

For example, if you decide to have a couple of drinks to help you feel better, you’re using a short-term strategy to manage your depression; alcohol might help you relax in the here and now, but it creates problems in the future—even the near future. Note that there’s nothing inherently wrong with having a couple of drinks, and this is the tricky part. The question is: Did the drinking result in behaviors that support or oppose your values? For instance, if you value your family, and drinking weakened your connection to them, that strategy did not work for you.

Many coping decisions make sense because they are a familiar part of the autopilot lifestyle. This is the paradox of depression. It seems as though what you’re doing would be beneficial, but it turns out that it isn’t. Again, this is usually because a short-term strategy is being implemented.

On the other hand, many of the vitality behaviors listed in the Depression Risk and Vitality Assessment are examples of long-term coping strategies. They’re done to promote your health and well-being over time. They’re much less concerned with addressing how you feel right now—although you can see immediate results with some behaviors—they’re more concerned with long-term vitality and wellness.

For example, to escape the depressed feeling you get from having to tidy your kitchen, you decide to go through your Netflix queue. You watch a movie, and when it’s over, you discover that little has changed, that you’re still as depressed as when you first sat down to watch the show—and the kitchen is still a mess. Instead, at the choice point in this situation, you might choose to go out and walk briskly for thirty minutes. Exercise not only releases neuropeptides called endorphins that are known to produce a positive mood and a sense of well-being, but it also helps improve your cardiovascular health and elevate your metabolism, which aids in maintaining a healthy weight. It even helps prevent Alzheimer’s!

The pitfall is that watching television seems easier than thirty minutes of brisk walking. What’s easier is infinitely more appealing than what’s harder, particularly when you’re depressed. And this is compounded by the belief that what changes your mood right away is preferable to what’ll change it over the long term. The paradox, and the problem, is this: Some short-term strategies help you feel better right now, but in the long run, they create more depression. Watching the movie only artificially changes your mood; exercise literally does it.

Once you gain new skills for shifting your perspective, you can choose positive coping behaviors, experience their benefits, and begin to build a new behavior pattern. You do this by learning to select long-term solutions over short-term strategies when you’re at a choice point.

Judy’s Story

Judy is a thirty-three-year-old mother of two children, ages nine and eleven. She has been married for twelve years. Her husband, a construction worker, usually drinks a few beers after work with his buddies before coming home. He often has a couple more beers at home. Judy began to feel depressed several years ago, after she discovered that her husband had an affair with a woman he met at the local watering hole. She chose to forgive her husband even though she felt terribly rejected by his infidelity and by his frequent comments about her physical appearance. Judy had gained weight after her second pregnancy and she believed that this triggered her husband’s interest in other women.

Judy believes that he drinks to avoid interacting with her, but she hasn’t said anything to him about it. She’s afraid that confronting him might cause him to leave her or start another affair. Because of her limited job skills, she doesn’t think she’d be able to make it on her own if he left her. She feels lonely but doesn’t see her friends because she doesn’t want them to know that her marriage is in trouble. Her day is basically organized around her household and childcare duties, reading magazines, watching TV, and napping. She enjoys being with her children, and she takes pride in her cooking and cleaning, but she had hoped for much more in life.

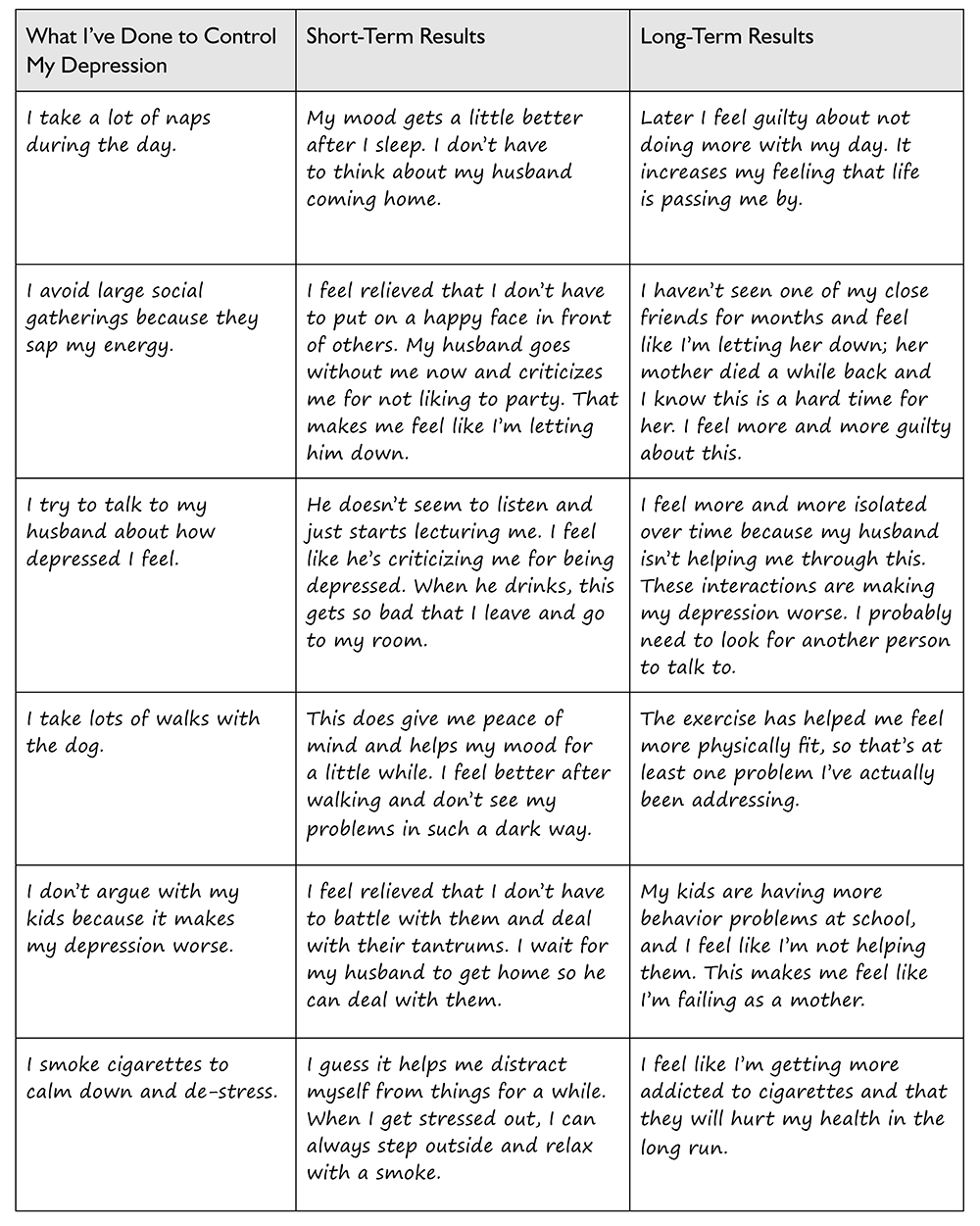

Let’s take a look at what Judy came up with when she took an inventory of her depressed behaviors and their short-term and long-term results. It’ll help you prepare for when you do the same, later in this section.

Judy’s Inventory of Short-Term versus Long-Term Results

In Judy’s answers, you can see the usual mixed bag of short- and long-term strategies that people use to try to control feelings when depressed. Notice that the strategies she assesses as least useful are basically avoidance behaviors (napping, smoking, and avoiding social situations and confrontations with her husband and children).

In reflecting on this exercise, Judy realized that she needed to stop using avoidance strategies that were not helpful. She puzzled over why she had used them for as long as she had. Judy reasoned that the avoidance strategies were easier and more familiar to execute than her more-active approach strategies. She heard a voice saying, “Just lie down and take a nap; you’ll feel better when you wake up… Just have a cigarette and focus on something else… Let your husband deal with the kids—he’s their father.” And those strategies made sense when Judy’s goal had been to control her mood. But her real goal—and yours—is to solve problems and live a vital life.

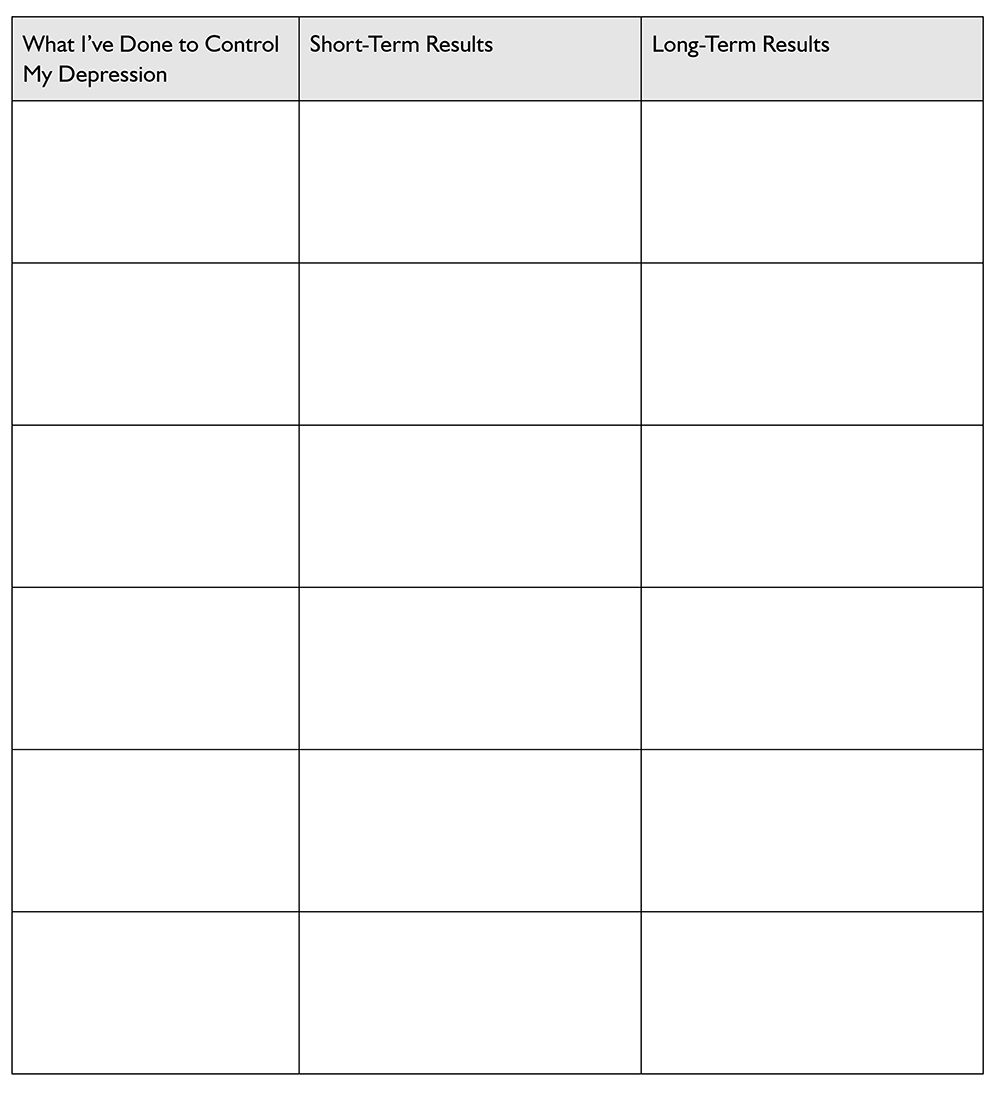

Inventory of Short-Term versus Long-Term Results

In this exercise, think back over the time since you first began to struggle with depression. In the left-hand column, describe the main strategies you’ve used to control your depression. Then consider the short-term and long-term results of each strategy, and describe those in the next two columns. If you need more space, print a copy from this book’s website (http://www.newharbinger.com/38457).

Further Exploration. What did you discover in this exercise? Were you able to identify some short-term coping strategies? When you step back and look at them objectively, how did these strategies end up working in the long term? Did you determine whether any of your strategies have helped in the long run? If so, you’ll want to use these strategies more often.

Depending upon your situation, you might have piled up a lot of short-term strategies that produce miserable long-term results. When your attempts to manage your depression don’t work in the long run, you know it because you don’t feel like you are living the life you want to live. Is your life working better than it did a month ago? A year ago? Is your life satisfaction improving or deteriorating? Are you living your life the way you want to live it? It’s important that you honestly look at whether a particular coping behavior is working or whether it’s hurting. If it doesn’t work, try something different. And ask yourself, “Does the new behavior work better?”

As mentioned, depression is fueled by avoidance of emotionally challenging situations. Avoidance strategies normally are short-term-relief oriented; their goal is to reduce or eliminate your emotional distress right now. But you do have a choice in which strategies you eventually select! In the exercise that follows, you’ll have a chance to play with the choices you have, both the short- and long-term ones.

Approach Versus Avoidance Inventory

To begin, either select an item you endorsed in the Depression Risk Inventory in chapter 2, or pick a different depression trigger in your life. Then, on the lines below, describe how you could avoid dealing with the situation, followed by how you could approach the situation. Try to describe these options in terms of behaviors.

Please don’t use this exercise as an opportunity to beat up on yourself; cultivate the kindness for yourself that you would give to someone else in your position. You’ve been doing the best you can, and this program will give you the new perspective and skills you need to make changes in your life. Just stick with us; we are your partners in change.

Relationships in my life:________________________________________

Strategies I could use to avoid dealing with the problem:________________________________________

Strategies I could use to directly deal with the problem:________________________________________

Work/study behavior:________________________________________

Strategies I could use to avoid dealing with the problem:________________________________________

Strategies I could use to directly deal with the problem:________________________________________

Leisure/play behavior:________________________________________

Strategies I could use to avoid dealing with the problem:________________________________________

Strategies I could use to directly deal with the problem:________________________________________

Health behavior:________________________________________

Strategies I could use to avoid dealing with the problem:________________________________________

Strategies I could use to directly deal with the problem:________________________________________

Further Exploration. This is another way of looking at depression triggers. In this exercise, did you detect problems you didn’t identify in the Depression Risk Inventory? If so, great. Do take these into account as you move toward experimenting with new strategies in dealing with problems in your life. If you didn’t note any new problems, then consider this exercise as confirming and perhaps further clarifying what you learned from your Depression Risk Inventory. Was it difficult for you to describe what you would do if you chose to deal directly with the problem? If you did, you are certainly not alone! The good news is that you can retrain your brain to pursue those long-term coping strategies more often.

When Judy did this exercise, she had some interesting observations on what was going on in her life and how her penchant for avoiding rather than dealing with life challenges was fueling the fire of her depression.

Relationships in my life: My marriage is going downhill fast.

Strategies I could use to avoid dealing with the problem: Neither one of us ever brings up the fact that we don’t get along. Instead we just nitpick each other and criticize what the other person does. I try to stay out of his way when he seems to be in a bad mood. I don’t let myself think about how unhappy I am; the prospect of having to deal with the marriage is just scary. I may end up being a single mother.

Strategies I could use to directly deal with the problem: I would have to sit down with him and have a heart-to-heart talk about what is going on in our marriage. We might need to get marital counseling. At least I could let him know that the relationship matters to me and that I want to try to save it.

Work/study behavior: I have not developed my job skills or created a career even though I intended to after my kids were old enough to stay at home by themselves.

Strategies I could use to avoid dealing with the problem: I have a lot of worry about going back to work. I know my skill sets are out of date, so I talk myself out of looking at job ads or talking to friends about my interest in a career.

Strategies I could use to directly deal with the problem: I could go to unemployment and get help with developing a résumé and a job search strategy. I could talk with my friends and get information on how they coped with going back to work after having kids. I can also ask them to keep an eye out for me—for just part-time work.

Leisure/play behavior: I have very few activities or hobbies that give me joy.

Strategies I could use to avoid dealing with the problem: I just don’t think about it. I do my housework, cook, take care of the kids, and call it a day. I tell myself that that’s all I need and that I don’t have the energy for anything else anyway. When friends call to invite me to go out, I make up an excuse for why I can’t go.

Strategies I could use to directly deal with the problem: I could look for hobbies that I can do at home, like sewing or reading. I could join a book club or just say yes to invitations. It would be easy for me to volunteer at my children’s school; they are always asking for parent helpers.

Health behavior: I’ve gained more than thirty pounds in the last three years, and I smoke too much.

Strategies I could use to avoid dealing with the problem: I’m afraid to quit smoking or change my diet because smoking and snacking are how I stay calm. I worry that I would feel more down and maybe even gain more weight if I quit smoking.

Strategies I could use to directly deal with the problem: I could get a fitness evaluation at the YMCA and maybe an exercise coach to help start a program. I could set a modest weight-loss goal so I would feel successful. I could call the quit-smoking line; I have it on the card my doctor gave me.

As her answers clearly show, Judy struggles with her tendency to avoid addressing her major life issues. In completing the exercises, Judy realized that she was spending too much time and energy on managing her feelings by avoiding things, and she also realized that she has good ideas about how she could deal with the big problems in her life.

Judy had the realization that her life was steadily going downhill and that she would have to be the one to do something to turn it around. She realized that the mess she was in was caused in large part by her reluctance to deal directly with her husband’s affair and his lack of accountability about it. So one night when their children were staying at a friend’s house, Judy brought up the affair and asked her husband to take responsibility for his behavior and apologize to her. She also informed him that his drinking wasn’t going to work for her and that he needed to get help. He got up and left the table without saying a word, got into his truck, and drove off.

Even as Judy wept, she felt released from her prison of silence, numbness, and isolation. At that moment, she accepted that she might not be able to save her marriage, but in her heart she knew she could and would create a better life for herself and her children. Her husband returned after a couple of hours and agreed to seek treatment for his alcoholism. He apologized for being unfaithful and insisted that it didn’t have anything to do with the way Judy looked but was more about his own insecurity and impulsivity. He asked her to forgive him, and this time he meant it. Judy was optimistic about going to counseling with her husband, but her first priority was continuing to focus on creating a vital life for herself, whether she shared it with him or not.

A unique feature of the workability approach to daily living is that it owes no allegiance to any doctrine about how to live life. A life worth living comes in about as many flavors as there are people. And how you get there isn’t about style points—it’s about getting out of life what you want out of life. As we said before: It isn’t about what should work, it’s about what does work. When you’re zeroed in on using workability as your guide, you’ll find yourself asking these kinds of questions:

- Is drinking to relax working for me?

- How has it been working for me to avoid dating?

- Is skimping on sleep working for me?

- Is not talking to my partner about our sexual problems working for me?

- Is not looking for a more satisfying job and career path working for me?

- What am I doing in my life right now that is working for me?

- What am I doing in my life right now that’s not working?

- Is working two jobs working for me in terms of my family life?

- How did my choices today work for me?

- Is waiting to be motivated to take a walk working for me?

- Is eating ice cream every night working for me?

- Is not going to church working for me?

It takes courage to ask workability questions. Very often, the mere fact that you’re asking means that you’ve begun to recognize a difference between what your mind is promising you and what you’re getting in terms of results.

So before we end this chapter, let’s size up the questions you might be carrying around about the workability of certain aspects of your life in the four life domains. Remind yourself that it is okay to ask workability questions without necessarily assuming that the answer is going to be negative. It is like checking the air pressure in your tires. You don’t know if there is a problem until you put the air pressure gauge to work!

In the space provided, write down your workability questions in the four key life domains: relationships, work/study, leisure/play, and health. They might resonate with ones we’ve just listed, or they might be totally different. You don’t need to answer these questions now—not yet. Just jot them down.

Relationships:

Work/study:

Leisure/play:

Health:

Further Exploration. Were you able to come up with some questions about workability in all of the life domains? If you did, welcome to the human race! There are few people in this world who have everything figured out in even one life domain, much less all of them. Because life is dynamic, unfolding, and challenging by nature, you can expect workability questions to surface, subside, and resurface over time. In some life arenas, you probably have an inkling of what’s not working for you right now. We will go into that in greater depth in future chapters.

One thing we want to make abundantly clear is that we aren’t blaming you for at times engaging in unworkable behaviors. We all do it. We understand how difficult it is to remain focused on living in accordance with your values. It’s why so many people experience symptoms of depression at some point in their lives. At the same time, there is a connection between your actions (or lack thereof) and the results you’re getting in life. We view this as a positive rather than a negative truth. You do have control over your behavior, even if your mind tries to bully you into following unworkable rules.

If you identify the strategies that aren’t working in your life right now, you can try something new. And trying something new introduces the opportunity for learning something new—and then trying something else. It’s all about variability in our behavior—experimenting, noticing, and noting the direction in which we want to head, of course! We think this classic Zen saying offers inspiration: The journey of a thousand miles begins with the first step. You are taking that step right now, and the journey is under way!

- Workability is a powerful tool designed to help expose rule following and test whether the rules you are following are actually working.

- To know what works, you must learn to notice your behavior and analyze the consequences of your behavior.

- Short-term strategies for coping with depression tend to be focused on controlling emotional pain.

- Long-term coping strategies don’t offer the quick fix you might want, but they provide stable, workable results that promote your sense of vitality.

- Ultimately, it’s better to solve problems than avoid them, and better to face difficult emotions than run from them.

- Taking inventory of how your lifestyle is working right now, scanning the horizon for depression risk situations, and forming a problem-solving plan oriented toward approach rather than avoidance can help you create a better life.