Chapter 4

Understanding the Mind and Mindfulness

Hold to the now, the here, through which all future plunges to the past.

—James Joyce

If living life on autopilot sets the stage for you to veer toward a depression-producing lifestyle, then the antidote is to create a lifestyle intentionally: one in which you choose to live in ways that expand you as a person. If rule following and the emotional and behavioral avoidance it produces lead you away from your inner vitality, then learning to approach and embrace all emotions, even those you don’t like, is a more positive path for relating to your inner space.

In the previous chapter, we gave you a chance to imagine what living an approach-based life would look like. But if it were that easy to turn your life around, you no doubt would have already done that—and you probably wouldn’t be holding this book in your hands. It might surprise you that one of the things making the change so hard for you is your mind.

Your mind is not necessarily going to cooperate in helping you achieve your goals. As we discussed in chapter 2, your mind is full of rules for you to follow, and it will incessantly tell you to follow them. Your mind has been programmed to tell you that controlling your depression—and all other sources of personal pain—is job one in life. Your mind wants you to assume that nothing else important can happen until you get rid of your depression. When it comes to this issue of emotional control, you and everyone else do indeed have a one-track mind.

We can guarantee you this: Your mind is not going to stop chattering at you about the virtues of control, suppression, and avoidance. And it is hard to ignore your mind, because it is always with you, and it is helpful to you in many ways. What is needed is a different way of relating to your mind so that you can listen to it when it pays to do so and follow your own intuitions when that is the better path.

In this chapter, we want to better help you understand how the mind functions and how cultivating your mindfulness skills can help you relate to your mind in a more productive way. To accomplish this important objective, we will delve deeper into the architecture of the mind using the perspective of relational frame theory. You will quickly see why you might want to take your mind’s advice with a grain of salt.

Along the way, we will discuss two major modes of mind that you have access to in daily living. One is based in the linear, rule-based system of language and social control and is likely to push you in the direction of emotional avoidance; the other originates in your values, intuitions, and passions and will lead you into a state of awareness of, openness to, and curiosity about your internal experiences—all while being engaged in the life pursuits that matter to you. One mode of mind is the source of suffering; the other is the source of inner calm, compassion, and vitality. In ACT, the goal is to help you use this second mode of mind to make you psychologically flexible. This involves you being able to stay in the present moment, stay open to and accepting of your inner experiences, and simultaneously engage in life pursuits that matter to you.

The mindfulness skills we teach you in this book contribute directly to psychological flexibility; they will help you to be present and open—receptive to your inner experiences—while increasing your ability to initiate and sustain a lifestyle that creates positive emotions and that is consistent with your values. In this chapter, you’ll have a chance to make direct contact with—really experience—what they feel like in practice.

We will end by giving you a chance to assess your mindfulness skills as they stand at present and then help you develop a plan for strengthening them. Remember: Neuroscience studies suggest that even a brief daily practice of mindfulness skills can result in quite rapid, permanent, and positive changes in brain functioning (Deshmukh 2006; Hankey 2006; Lutz et al. 2009; Davidson and Begley 2012).

Welcome to Your Mind!

In this book, we use the word “mind” to refer to the ongoing process of fusing with and reacting to thoughts, feelings, memories, and sensations. The mind is not a thing in the literal sense. Instead, it is a dynamic, unfolding process in your awareness. When you’re fused with your mind, you’re likely to obey its instructions, just as a child minds a parent. Only you can relate to your mind, because no one else has access to the word machine inside your head. It’s just you and your mind going at it. Your relationship with your mind is unique and determined by your learning history. In this way, no two minds are alike, even though we are trained from birth to comply with similar social rules, norms, and expectations. For a moment, we want to examine how the mind originates within the operating system of language and thought.

RFT holds that human language and thought originate from a surprisingly small number of symbolic relations called relational frames. Examples of these core relations include now/then, if/then, and here/there, to name a few. RFT researchers are very interested in how these frames develop, expand in number, and multiply to create the vast capabilities of human language.

The most basic relational frame in language is the deictic frame. The deictic frame establishes that I am different from you, and this is the very beginning of the ability to adopt a point of view wherein my point of view is different from your point of view. Very young children can’t engage in this type of relation, so they’re unable to distinguish the emotions of others from their own emotions. If a parent starts crying in front of a year-old infant, the infant will also start to cry.

Acquiring the ability to frame deictically is the beginning of conscious self-awareness. Indeed, in Buddhist philosophy, it is this emerging sense of self as separate from others that is the first cause of human suffering. Once you know that you are separate from others, you can begin to evaluate how you are different from others. This leads to a whole host of potential sources of suffering.

Deictic frames also allow us to distinguish things from the perspective of the observer: here and there, now and then, and so on. In language, this allows us to make such statements as “The photograph is there, in front of me” and “I was five in this picture; now I’m fifty.” In thought, it allows you to clearly distinguish between “me” and “my mind,” such as being able to say, “I’m having the thought that I’m sad about where my career is headed.” Turning the deictic frame inward can be very difficult, as it might not feel intuitive or even true at first. But once you’ve established the relation “me and my mind,” you’re able to say, “I’m having the thought that I’m lonely” or “I’m having the feeling of being sad.” And this is a major step toward improving your ability to stay in the moment, open to your experiences—and transcend depression.

At first, this distinction may seem surprising, maybe even mind-boggling, but just as you aren’t the same person as someone sitting across from you, you aren’t the same as your mind. It’s more accurate to say that you are able to observe your mind’s activities, but, as the observer, you are separate from your mind. Learning to step back from unworkable rules produced by the mind, therefore, comes down to strengthening your ability to deictically frame in an inward direction, be it through the practice of meditation, prayer, mindfulness exercises, or a combination of these. Now there’s a paradox—using the word “mindfulness” to describe a way of separating yourself from your mind! Luckily, that one’s just semantic.

![]()

The activities of mind are so subtle and hard to apprehend by nature that we tend to take them for granted. On the surface, it seems essential and correct to use the mind as the go-to for daily functioning. It helps us organize, plan, predict, and engage with the world. The reality, however, is that the mind is just an operating system. The mind displays output at a constant rate on the screen of your mind’s eye on a 24/7 basis. But don’t mistake the operating system for the computer that houses it! Like any operating system, the mind is not as capable as you might think it is. This guided audio exercise will help you understand this counterintuitive idea.

Get an egg out of your refrigerator, hold it in your open palm, and concentrate on it for a minute. What do you see? What do you feel? You see a white or brown shell, with a smooth, slightly sandy texture. Now notice how perfectly made the shell is in terms of its function. The entire structure is necessary for the shell to do its job. It is built exactly right and has been that way since the moment it came into existence as a tiny, tiny shell. Can you see the location where the shell started to become a shell? Is there an obvious starting point? What was the last part of the shell to grow? And finally, what is the living part of this egg? The shell—or what is inside the shell? When you are ready, return to the book to complete the remainder of this exercise.

Now that you’ve had a chance to really study the shell, you may be thinking how perfectly designed it is for the job it has to do. Now, let’s change the context a little and see what happens to the shell. What if we asked you to let the egg drop onto a floor? Would you resist? Perhaps you would, as you know that would result in the end of the egg in its current form—and a mess on the floor!

The shell, as perfect as it is for providing a lightweight protective covering for the potential life mass inside, is not designed to protect the life mass from every possible physical insult. If you dropped the egg on your bed, it would probably make it, but not if you dropped it on the floor. Something that’s a perfectly protective cover in one context can turn out to be exactly the wrong form of protection in a different context—just like your mind!

![]()

Cracking the Shell of Language

If the mind is like an egg, the shell is the operating system of language and thought. The main products of this system are thinking, feeling, remembering, and the awareness of physical sensations within the body. It turns out that this shell grows and matures just like an eggshell, and it’s also very brittle. How brittle is it? The following guided audio exercise has been used for decades (and in Hayes, Strosahl, and Wilson 1999, 154–6) to demonstrate the transparent nature of language and thought.

First, think of the word “orange.” Let all the sensations, memories, and images associated with that word come into your mind. Do you sense the tangy odor or the texture of the peel? Can you imagine the slightly bittersweet taste? Do you see color? Can you see the sections of the orange in your hand? Can you sense the gush of juice as you bite down on a section? Give yourself a minute or so to get a full picture of an orange in your mind’s eye.

Now find a clock with a second hand on it. For the next forty-five seconds, we want you to say the word “orange” over and over again as fast as you can. Just keep saying the word as fast as you can until the forty-five seconds are up. If you have trouble pronouncing it or lose your concentration on the task, just get back to it and keep repeating the word as best you can. Time to start. Go!

When you are ready, return to the book to complete the remainder of this exercise.

What happened to your relationship with the word “orange” as you did this exercise? Did you notice that the more you repeated the word, the more it started to sound like gibberish? Did you have more trouble pronouncing the word over time? What happened to the images and associations you had in the first part of the exercise? Did they disappear?

Let’s consider the implications of the orange exercise for a moment longer. Initially, when we asked you to use the word “orange” as it’s supposed to be used in your language system, the system functioned beautifully. It gave you not just the word “orange” but a variety of images and associations from your past history with oranges. Then, when we asked you to use the word in a way that violates the rules of the system, it turned into an odd collection of sounds, mostly devoid of images and associations. You were simply uttering a sound that had no functional connection to your shell. You could try this again with almost any word and the result would be the same.

Activities like this essentially crack the shell of language and reveal its limitations, which often has a freeing effect on people. Once you realize how context dependent your reactive mind is, it is easier to react to it with skepticism, particularly when it involves dealing with your inner space. There is some formidable and essential wisdom in this part of your awareness, just as the essence of the egg is not the shell but what’s inside the shell. The reason the egg is there isn’t because of the shell. If there wasn’t any life mass inside, there would be no need for the shell in the first place.

Learning to recognize that your shell is different from your essence is fundamental to living a vital life. You are the life mass, and although the shell protects you in some contexts, it’s ineffective—or worse—in other situations. We’ll help you learn when you can use your shell and when you need to shed it so you can access other important aspects of your mind. Don’t worry about cracking the shell of language! It’s very robust and will pull itself back together quickly.

The Two Modes of Mind

Functionally speaking, the mind is organized into two main modes: reactive mind and wise mind. One mode (reactive mind) involves the linear, analytical, judgmental problem-solving operations of the mind. These activities are largely based in the semantic processing and reasoning areas of the brain. The second mode (wise mind) involves nonverbal forms of intelligence such as intuition, prophecy, inspiration, creativity, compassion, transcendent experiences of self, morality, and so forth. The mental abilities of both modes reside in distinctly different regions of the brain. Thus, the brain seems organized to give us two different ways to approach, understand, and respond to events inside and outside our skin.

The problem in depression is that the verbal, analytical mode of mind dominates awareness, squeezing out the nonverbal forms of knowing. In the sections that follow, we examine this dichotomy a little more closely, because it points directly to the question of why mindfulness practice will be such a powerful ally in retraining your brain to help you transcend your depression.

Reactive Mind

The reactive mind is a direct creation of your language system. It is linear, judgmental, and directive in nature. It chatters at you, wants to discourse with you, and serves up an unending stream of “woulds,” “shoulds,” “musts,” and “oughts,” regardless of whether its advice is wanted or needed. Your reactive mind is full of judgments, categories, comparisons, and predictions. It strings together concepts that describe who you are in the here and now and how you got to be the way you are. It will tell you that you don’t have enough of something, like love in your life, and too much of something else, like body hair or fatty tissue around your waist. It tells you what will happen if you engage in some behavior (“If you leave your job, you’ll never find another one”) and what will happen if you don’t (“If you don’t quit, your boss will keep insulting you and you’ll have no self-esteem”). This type of comparative, evaluative, and predictive activity is a breeding ground for depression, because overidentifying with the products of your reactive mind can get you caught in the trap of rule following and make you unable to adapt. In Buddhism, the reactive mind is viewed as a small and limited form of self that must be held lightly in order for you to cultivate healthier forms of self-experience.

Let’s be clear: We aren’t trying to bash reactive mind across the board. In many life circumstances, such as when you’re planning a work task, balancing a bank account, or crossing a busy intersection, reactive mind is very useful. As we noted earlier, reactive mind is able to plan, evaluate, and predict with considerable success in the external world. We would be lost without its organizational and problem-solving functions.

The problem is that the functions of reactive mind creep into areas where they are not useful. This includes making unhelpful evaluations, comparisons, or predictions about your thoughts, emotions, memories, self-worth, and how others perceive you, to name just a few. In these inner-world situations, reactive mind backfires miserably, causing your behavior to be governed by unworkable rules that foster emotional and behavioral avoidance. Further, and as we discussed in chapter 2, the rule following that originates in reactive mind directs your attention away from the actual real-world results of your behavior, thus making it difficult for you to identify strategies that don’t work.

Remember Bob from chapter 2? After his family left, this is exactly what he had to confront. His reactive mind was telling him to avoid being with his friends or setting up visitation with his children because he would just be a burden to them. His reactive mind was advising him to engage in a strategy designed to control his depression, but the strategy actually made his depression worse. His reactive mind advised him to work even more than he had prior to losing his family and to stop feeling sorry for himself.

The more Bob followed this advice, the more he struggled with anger and sadness, and the more often he resorted to drinking alcohol to relax and to sleep. Drinking, of course, did not stop the mental chatter of his reactive mind. It kept telling him, “Other people are able to take care of their patients and make time for their families. Why can’t you?” Bob’s mental advisor simply couldn’t admit that its strategies were never going to work, because it didn’t have another plan of action to offer. Until Bob learned to listen to his direct experience, he was powerless to resist the constant chatter of his reactive mind.

Wise Mind

It was Buddha who coined the term “wise mind.” Wise mind is deeply rooted in basic awareness and the nonverbal forms of knowing that surface when we can separate ourselves from the incessant chatter of reactive mind. The Dalai Lama likened wise mind to the clear blue sky that remains after the clouds created by reactive mind have been removed (Dalai Lama, Lhundrub, and Cabezon 2011). He suggests that the wise mind is the final source of the you that you know as you. It is the repository of consciousness itself, and this is something you have been in touch with since you first became an aware human being.

There is something comforting, safe, and secure about simply being in contact with self-awareness. This experience doesn’t change, even when things are changing all around you in the external world. In this way, the wise mind can become a sanctuary when you are in troubled waters. It is in the sanctuary of wise mind where you really grab hold of the sense that you are here, now, and alive. Your senses come alive such that you become much more tuned in to what is going on inside your body (for example, your rate of breathing, heart rate, sensations in your limbs) and on the outside as well (for example, seeing colors and hues differently, noticing new smells, seeing your partner’s face differently).

When you make sustained contact with wise mind, you may also have a sense of being interconnected with all things and experience a deep sense of compassion for the suffering of others and yourself. Self-compassion, as we explain later in this book, relieves you of the burden of having to be perfect in order to be worthy of your own kindness and affection. When you sense that you are interconnected with everyone, you quickly realize that everyone has flaws and shortcomings. Welcome to the human race!

Remember the egg we had you experiment with before? Wise mind is the essence inside the shell; it is what persists underneath the brittle surface of language and conceptualized versions of self. It is not defined by thoughts, feelings, memories, and sensations. Wise mind can see the shell of language and thought for what it really is, not what it says it is. The shell has a specific purpose that is important and useful in the right situations. But its use is ultimately limited—as is reactive mind, which depends on language and thought, and the limited context of verbal rules, to function. By contrast, because it is not in the world of evaluation, labeling, comparison, or prediction, wise mind is naturally curious, empathic, and focused on the here and now. It is fearless in standing in the presence of immediate experience and is keenly interested in the you that is doing the experiencing.

Much of the work we ask you to do in this book and on your own is to continually and patiently shift from the mode of reactive mind to the mode of wise mind. With patience and practice, you will get better and better at making this very important shift! In fact, an easy way to start is to give your reactive mind a nickname. Go ahead, try it—the sillier the better. Maybe a name like “Blow Hard” or “Know It All” or “Inner Critic” will get you thinking. As soon as you name it, you’ve made an important distinction between you and your reactive mind—and this is an important step toward being able to access your wise mind when you need it.

Wise Mind and Psychological Flexibility

Spending more time in the mode of wise mind will lead you to have greater and greater levels of psychological flexibility. Wise mind inherently involves being in the here and now, open to and curious about even painful inner experiences, and in touch with your overarching life principles. This is not only good for your health and well-being, but it also helps to quickly turn the tide on your depression. Wise mind mode frees you from rule following and having to use avoidance strategies, because when you are in the sanctuary of wise mind, there is no need to run from your own experience of being human. You can roll with your inner experiences instead of resisting them, focus on being present and in the moment, and base your actions in your beliefs about what matters to you in life. This is when the fun begins!

Note that even psychologically flexible people can fuse with unworkable rules and behave in values-inconsistent ways at times. However, they possess the mindfulness skills necessary to keep them moving in the direction of their values, and they can “get back in the game,” even after going through a challenging period in their life. Prior to moving on to a discussion of the mindfulness skills that produce psychological flexibility, it will be useful to examine each of these three core attributes of psychological flexibility—awareness, openness, and engagement—in more detail.

Being Aware

Being aware is the ability to be present, in the moment, and to pay attention to what is in front of you in a flexible, effective way. It is no accident that almost every meditative tradition emphasizes some type of breathing or attention-focusing task. It is a widely accepted spiritual truth that being present is the portal to peace of mind and transcendent experiences.

On a more mundane level, being aware of what you are doing as you do it is the solution for many of the problematic results of automatic living, including depression. Being aware is the skill that keeps you tuned into what is actually happening around you. This allows you to notice mistakes and learn from them, rather than slipping back into following unworkable rules that your mind is giving you. When you are paying attention, you don’t tend to pick mindless, automatic behaviors; you can see their unhelpful consequences and instead choose a behavior that is beneficial to you.

Sadly, the ability to be “here and now” is seldom valued or taught in Western culture. It is often labeled as a New Age idea that is practiced only by weirdos and monks. We are taught instead that automatic living is the preferred way to go: Complete your daily routines, follow the social conventions you’ve been taught, and turn your life over to the system, and your depression will surely give way to happiness. Unfortunately, you may not choose daily routines that actually support your health, and the pace of daily living may not allow you to smell the roses, so to speak. What a shame, because intentionality in choosing daily routines is critical—and the roses do smell good!

The ability to be present on purpose also supports your ability to treat yourself and others with compassion and kindness. For example, you may find that you’re less likely to judge a friend who has done something that hurts you. You may even become aware of things you did unintentionally that contributed to the problem. When you suffer a setback or make a mistake, being able to get present and pay attention to your reactive mind’s harsh judgments of you will allow you to treat yourself with kindness and self-acceptance.

Being Open

Being open is the ability to take an accepting, curious, detached stance toward all of you inner experiences. All humans have an unending cascade of thoughts, emotions, memories, images, and physical sensations, all of which are experienced privately. However, people vary widely in how they respond to these experiences. A basic difference has to do with whether they approach or avoid the distressing, unwanted internal experience. While avoidance works sometimes, such as when you jerk your hand away from a hot burner, habitual avoidance of painful emotions and thoughts exacts a heavy toll on a person’s quality of life. On the other hand, taking an open, curious, receptive stance reduces the need to control, avoid, or numb uncomfortable feelings, and it allows you to move forward in chosen directions.

Let’s say you want a new job and you find a possibility. You send in your information, and you’re called in for an interview. With each step, you may naturally experience some anxiety and apprehension. You may have some tightness in your chest when you think about the upcoming interview, and you may notice thoughts such as, “What if I get so uptight that I screw up the interview?” If your response style is one of avoidance (being closed), you can easily get caught up in trying to control these unpleasant thoughts, which saps your energy, diverts your attention, and may actually prevent you from succeeding in the interview. If your response style is one of approaching (being open), you can simply notice the feelings and thoughts that come up around your vulnerability and continue to invest your energy in moving forward with your plan.

Being Engaged

Being engaged is the ability to approach situations, events, or interactions with the intent of acting according to your values, even if doing so involves experiencing painful emotions, distressing thoughts, disturbing memories, or uncomfortable physical symptoms. When you engage life, you take the bull by the horns. You can focus on solving difficult personal problems. You accept the reality that distressing, unwanted experiences often are part of living a valued life. For example, an engaged person might seek out a friend who had said something hurtful and try to move through the problem, even though the conversation might be tense. Although there’s no guarantee that addressing this conflict will restore the relationship, an engaged, approach-oriented person would do it anyway.

In contrast, when you’re disengaged you tend to withdraw from situations that are emotionally upsetting and challenging. You might believe in letting the situation take care of itself, rather than messing with it and possibly making it worse. Alternatively, you might overfocus on getting out of the situation and take an impulsive or aggressive action that conveys a lack of attention to the needs of others. For example, you might decide not to talk with a friend who hurt your feelings, based on the belief that another bad interaction might end the friendship altogether, or you might decide to tell your friend off, thinking that that is what your friend deserves. In reality, your friend may not even be aware that you feel hurt.

Being disengaged can feed the cycle of depression because many challenging life situations will only get worse if you sit back and wait for them to get better on their own, or if you lash out and offend others. This style of withdrawal or impulse actions may also increase your sense of being out of control and trigger a variety of additional negative emotions, such as frustration, anger, rejection, or shame.

Five Facets of Mindfulness

Defining the core features of mindfulness has spurred a hot debate in psychology and in the religious community. The term “mindfulness” is actually somewhat of a misnomer, because most of the core skills involve learning how to get out of your mind, not get fully into your mind. But it would be a hard sell to call this “mindlessness training”!

Pioneering research by Ruth Baer and colleagues (Baer et al. 2006; Baer et al. 2008) was done to shed more light on the core features of mindfulness. If it is not a single trait ability, then what it is? Baer and her research group compiled all of the known existing self-report scales of mindfulness and then administered all of their items to several large samples of subjects, ranging from college students to people seeking psychotherapy for mental health issues. Her findings suggest that there are five distinct skills, or facets, of mindfulness. As the term “facet” suggests, each skill complements the other skills, much like each facet of a diamond contributes to the overall luster of the diamond. The more facets of mindfulness you learn to cultivate, the greater the level of your psychological flexibility will be across the board. We have organized section 2 of this book to help you understand, practice, and strengthen each facet so that your diamond shines bright.

Using Baer’s five-facet approach, we define mindfulness as a set of unique mental skills that, taken together, help you get present and pay attention to your thoughts, emotions, sensations, and memories in a curious, receptive, nonjudgmental way (see also Kabat-Zinn 2005). Mindfulness involves cultivating a sense of being interconnected with all people and all things, and extending compassion toward the suffering of self and others. Most important to our way of thinking, mindfulness involves being aware and intentional in your daily actions. This allows you to experience life on purpose and to link your daily actions to the things that you value in life.

![]()

We want you to learn more about what each facet of mindfulness is and what it looks like in daily practice. To that end, we’d like you to complete a survey known as the Five-Facet Mindfulness Questionnaire—Short Form (Baer et al. 2008). In the sections that follow, we briefly describe each of the five facets and then provide a format for you to complete a short self-assessment of your skills in that area. While this may sound a bit technical, the results provide crucial information for you to use in transcending depression and creating a vital, purposeful life! In fact, we suggest that you periodically repeat this survey so you can see how your mindfulness skills are improving with the brain training practices we will introduce you to in section 2.

Facet 1: Observe

Observing skills consist of being able to “just notice” things that are happening both inside of you (physical sensations, thoughts, feelings, memories) and outside of you (sounds, sights, colors, smells, activities of others). In observing mode, you hold still mentally and focus attention in a singular way—as if you are using the zoom function of a camera lens.

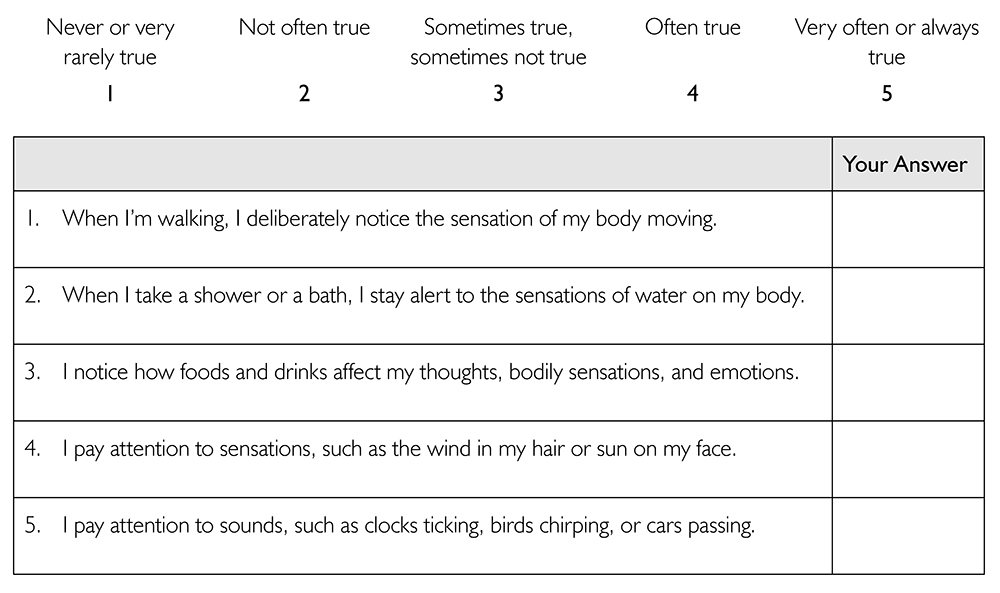

The following items of the FFMQ represent the Observe facet. Using the 1–5 rating scale below, please indicate in the box to the right of each statement how frequently or infrequently you have had each experience in the last month. Please answer according to what really reflects your experience rather than what you think your experience should be. When done, add your answers to get your total Observe score.

Further Exploration. Take a moment to review your individual answers to these questions. Did your ratings tend to vary a bit? Most of us differ in our ability to observe different aspects of the internal or external world. For example, you may find it easy to tune in to bodily sensations but find it difficult to notice thoughts, feelings, or memories that are showing up. Your abilities may also change depending on the situation you are in (for example, while riding a bus to work versus lying in your bed at night). Some people may be able to pay attention to sounds and colors in their environment, while others can more easily attend to internal sensations like breathing. The good news is that you may be able to use your strengths in one area of observing to grow in your abilities in other areas.

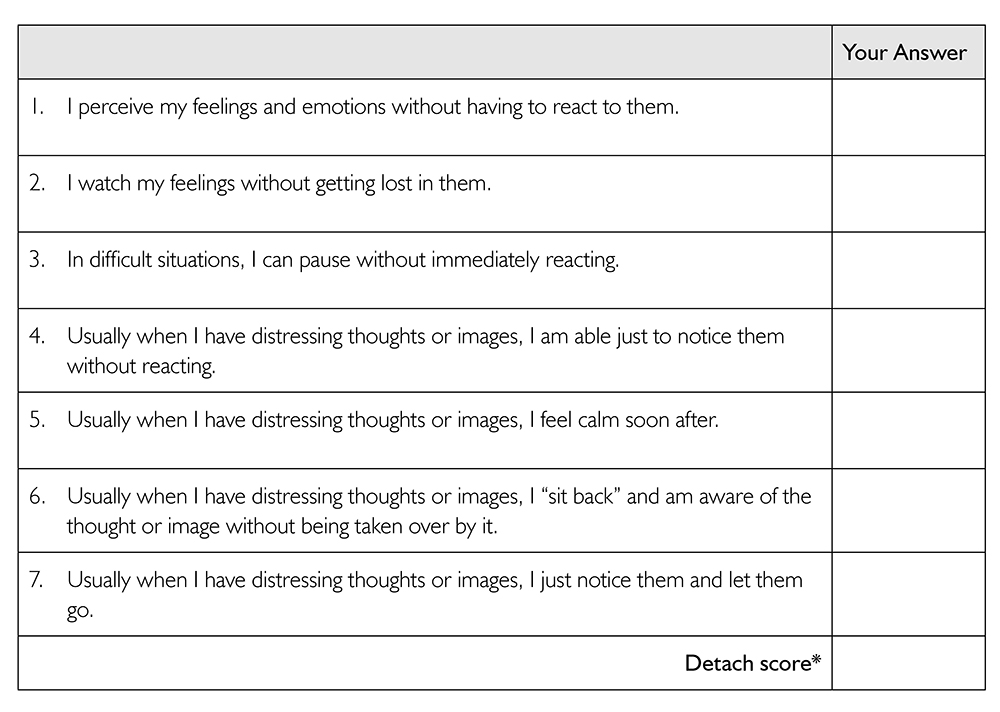

Facet 2: Describe

Describing refers to your ability to use words to organize and convey what you are aware of either inside or outside of you at any moment in time. Some people use the phrase being a witness. The job of the witness is to just tell the truth, the whole truth, and nothing but the truth.

There are several core features of being a witness. First, witnessing needs to be anchored in the present moment, as it unfolds in front of you. For example, witnessing involves being able to label strong emotions at the moment you make contact with them, such as feeling both sad and ashamed after you get into a heated argument with your partner and say some mean things.

Second, descriptions of direct experience must be as objective as possible. This involves a focus on the immediate qualities present using descriptive words. For example, in describing sadness a witness might say, “My eyes are tired and want to close… My body feels heavy… I’m having the thought that I don’t want to be in this relationship.” The witness does not use the mind’s interpretations or judgments of events—these would come out as evaluative words (“I shouldn’t be feeling sad… I’m wrong to want to leave this relationship”) The witness simply describes events to the fullest extent possible, without inserting judgments about them.

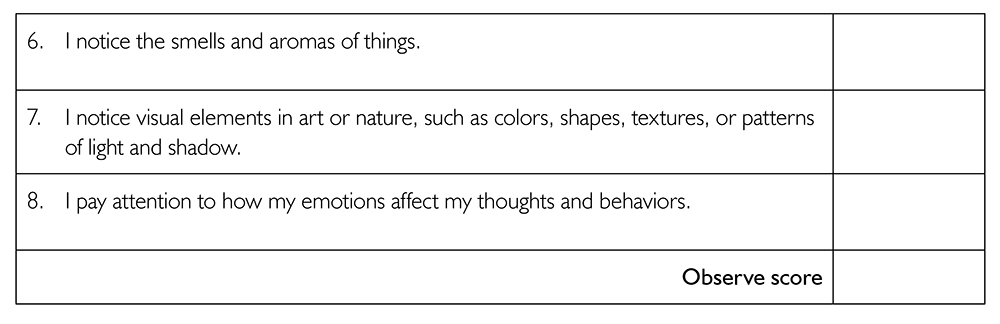

The following items of the FFMQ represent the Describe facet. Using the 1–5 rating scale, please indicate in the box to the right of each statement how frequently or infrequently you have had each experience in the last month. When done, add your answers to get your total Describe score.

Note that for questions 3, 4, and 5, you will need to subtract the number associated with your answer from 6 to obtain the adjusted score for the item. For example, if your answer to statement 3 is 4 (often true), you will subtract 4 from 6 to get an adjusted score of 2.

Further Exploration. Take a few moments to look at your answers to the individual items. Did you notice differences in some of the ratings? For example, is it harder for you to describe what you are experiencing when you are upset but much easier for you when you are just feeling normal? Think about your ability to use descriptive words that are closely tied to the direct qualities of an experience, while avoiding evaluative words that give positive or negative meaning to an experience. Whereas we want you to attach to descriptive words and develop your vocabulary in that area, we want you to detach from labels that create a positive or negative evaluative tone. Try to look at the pattern of your responses and see if there is an area of describing skills that you would like to shore up with practice.

Facet 3: Detach

To detach means that you dispassionately allow any thoughts, feelings, memories, and sensations to simply be present without becoming absorbed in mental evaluations of them. Detachment is sometimes described as letting go. When you can detach from a thought, feeling, or sensation, you are able to notice that private experience without getting lost in trying to analyze it. In a sense, you are willing to just let experiences be there and let it play out in your awareness. This is difficult to do, particularly when the thoughts are compelling, the feelings are painful, and the memories create the impression that we are reliving the past. We want to avoid pain and suffering, and so we have our own unique escape strategies. Detachment skills help us develop the ability to notice the appearance of an escape move and stay present with whatever it is that we want to go away.

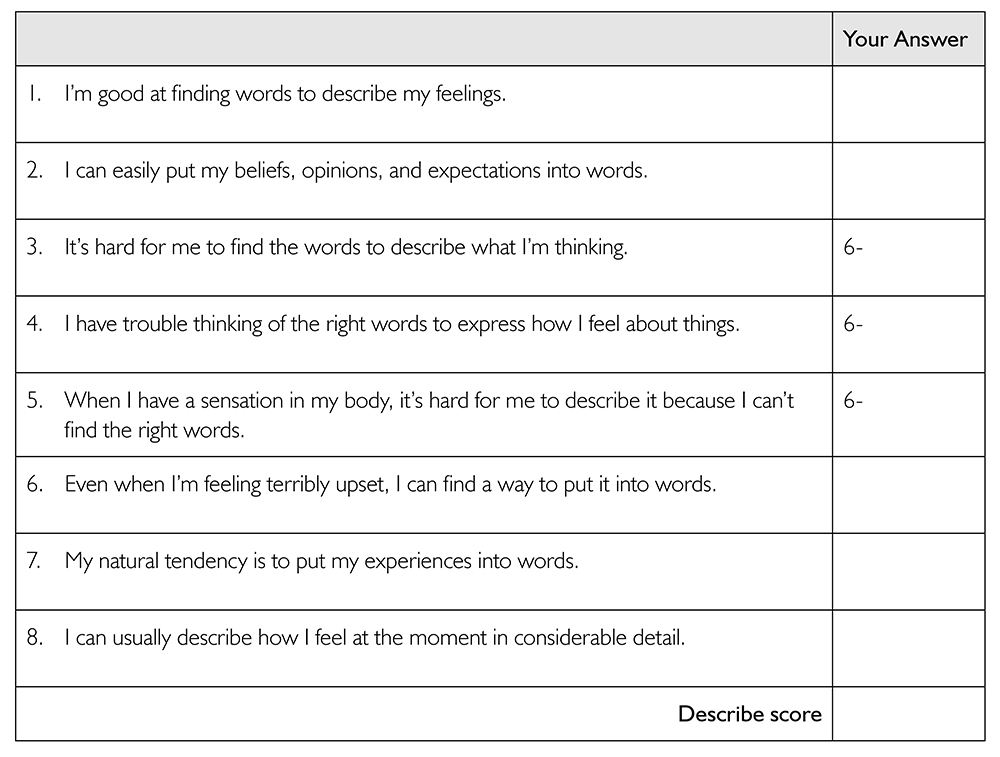

The following items of the FFMQ represent the Detach facet. Using the 1–5 rating scale, please indicate in the box to the right of each statement how frequently or infrequently you have had each experience in the last month. When done, add your answers to get your total Detach score.

Further Exploration. Take a moment to think about your strengths in this area. Do you find it easier to detach in some contexts more so than in others? For example, is it easier to detach when a coworker makes a snide remark than it is when your spouse criticizes your appearance? Do you tend to overreact to and fuse with certain types of feelings but not others? Do you have some ideas about particular methods or strategies that you can use to activate your detachment skills? Sometimes saying something as simple as “Breathe in and let go” can serve as a reminder that it is time to step back and give yourself some inner breathing room.

Facet 4: Self-Compassion

The ability to practice acceptance and kindness to yourself is a powerful tool for creating a state of wise mind. This is sometimes referred to as practicing self-compassion. It is an important concept in Buddhist writings about human suffering and how to relieve it. The potential benefits of treating yourself with care and kindness are garnering more and more attention in the depression-treatment literature. People caught up in depression behaviors tend to overuse self-criticism and may, at some level, believe they are unlovable and unworthy. Practicing self-compassion involves adopting exactly the opposite stance—totally accepting yourself, flaws and all.

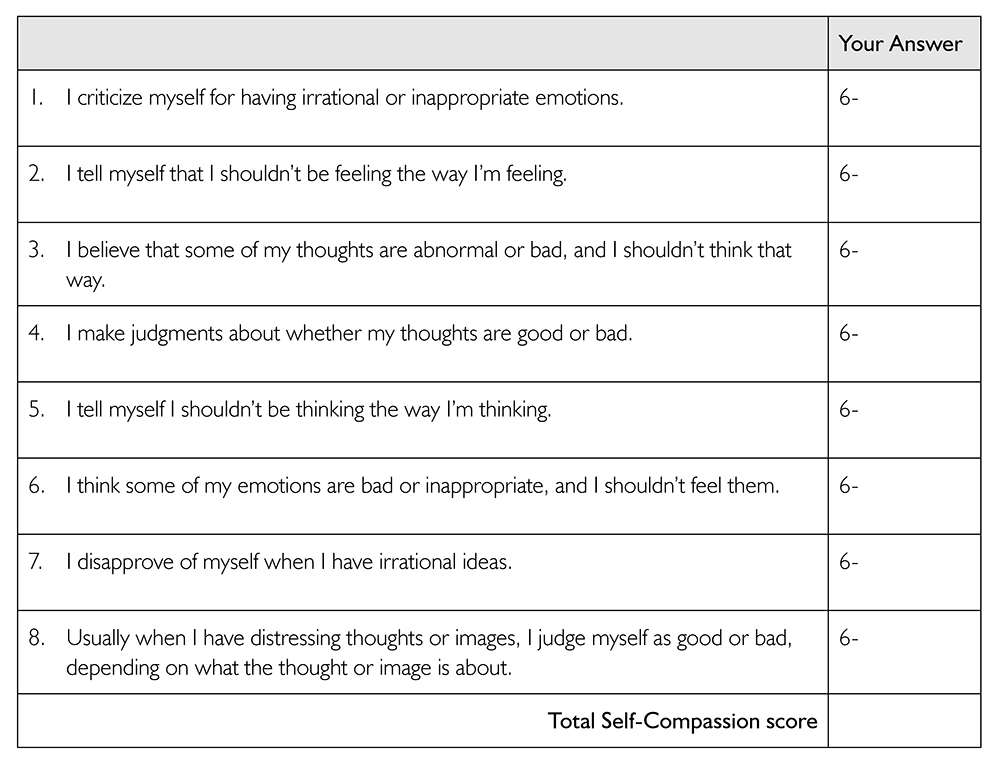

The following items of the FFMQ represent the Love Yourself facet. Using the 1–5 rating scale, please indicate in the box to the right of each statement how frequently or infrequently you have had each experience in the last month. When done, add your answers to get your total Self-Compassion score.

Note that you will subtract the number associated with your answer from 6 to obtain the adjusted score for all items. For example, if your answer to statement 1 is 2 (not often true), your adjusted score for item 1 will be 4.

Further Exploration. Take a few minutes to go back and review your answers to these questions. Completing this facet is usually an eye-opener for depressed people, because they tend to be their own worst critics. Did you notice that it is hard for you to accept difficult inner experiences without criticizing yourself? When you get lost in your reactive mind’s judgments about how you are doing, it is very difficult to cut yourself some slack. Remember that self-compassion is unconditional; it is an attitude of deep respect that does not depend on your performance or accomplishments, and it does not rely on approval from others. People who cultivate self-compassion show concern for their well-being; can experience failures, setbacks, or disappointments without getting lost in self-criticism or self-rejection; and are willing to walk into their pain—and they do all of this with a sense of warmth and gentleness.

Facet 5: Act Mindfully

Acting mindfully means being aware of what you are doing as you are doing it. This is sometimes called acting with intention. Acting with intention means being squarely located in the present moment and behaving in a way that reflects your beliefs and principles. The experience of intentional action is qualitatively different than the automatic-living mode that is characteristic of depression. Rather than going through each day in a haze, acting mindfully brings you to your senses so that you can choose each activity based upon your values.

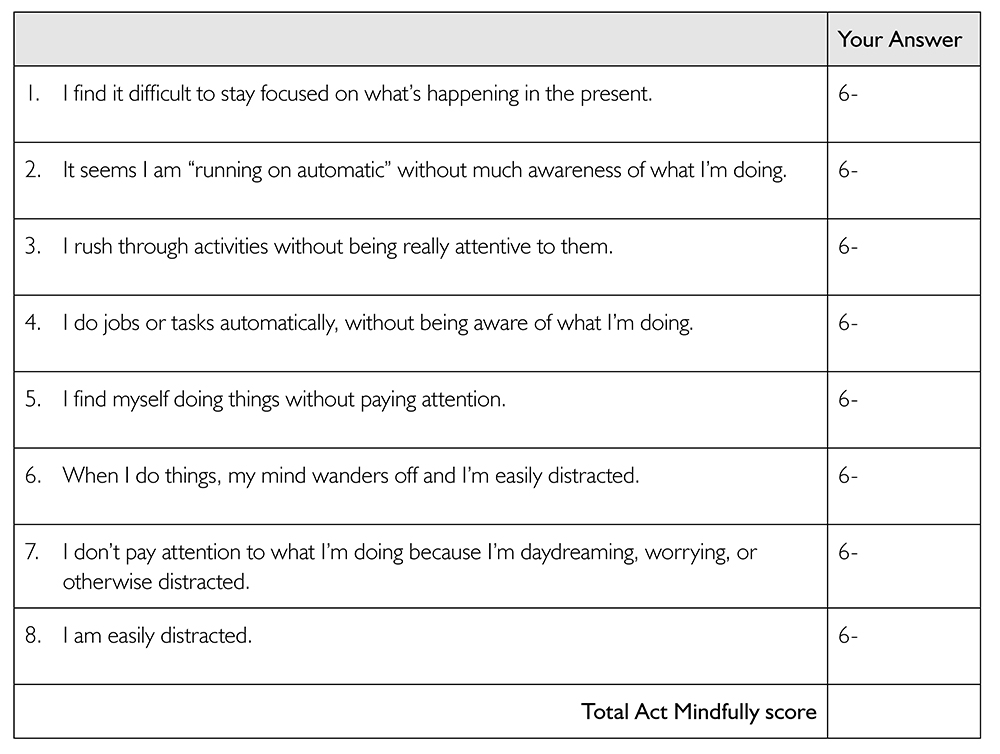

The following items of the FFMQ represent the Act Mindfully facet. Using the 1–5 rating scale, please indicate in the box to the right of each statement how frequently or infrequently you have had each experience in the last month. When done, add your answers to get your total Act Mindfully score.

Note that you will subtract the number associated with your answer from 6 to obtain the adjusted score for all items. For example, if your answer to statement 1 is 2 (not often true), your adjusted score for item 1 will be 4.

Further Exploration. Take a few minutes to carefully review your answers to each item of this facet. Do you tend to go on autopilot for some activities but not others? Which activities are most likely to lull you into an automatic mode of living? Are there situations in which you are much more aware and intentional? Of all the facets of mindfulness, being intentional is where the rubber meets the road and, because of that, it is the most demanding of the five mindfulness skills. Think about ways that you could deliberately increase your daily level of intentional action.

Putting It All Together: How Mindful Are You?

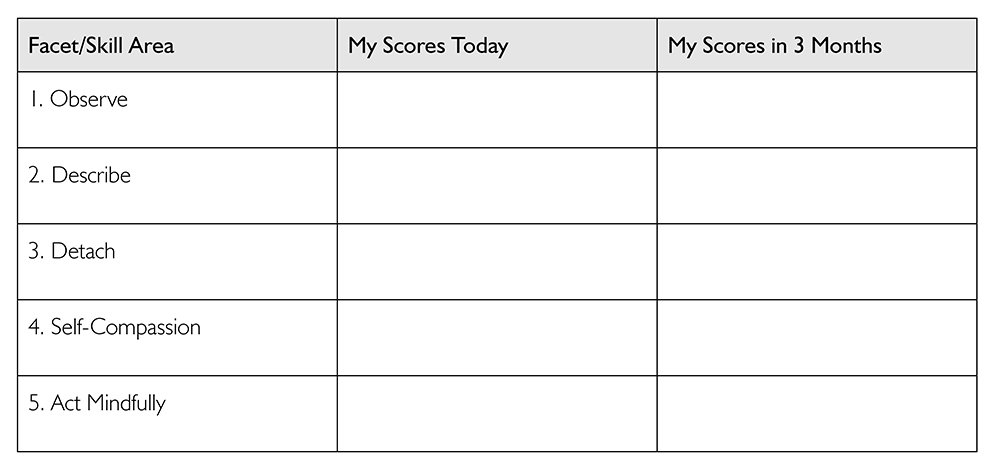

Now it’s time to summarize your assessment results to create a profile of your five-facet mindfulness skills. Record your scores for each facet in the table that follows. Notice that we include a column for your scores three months from now, because we would like you to complete this survey again to help gauge the impact of additional exercises we introduce later in this book.

Five-Facet Mindfulness Questionnaire Summary Sheet

Targets for Mindfulness Practice

Reflect on your scores for each of the five facets now and develop a mental image of what it would be like if your skills were even stronger than they are today. For example, you might have a decent score on the Observe facet; imagine what it would be like to have a superhigh score, meaning you were able to practice observing even in the highest depression-risk situations. What would life be like if you got really good at loving yourself and practicing self-compassion in a moment of suffering? What if you beefed up your detachment skills such that you could pull yourself out of a spiral of rumination and worry, even in a high-conflict situation? Would life be better if you could do even one of these things a little better? We think so!

A Formula For Radical Change

The way to transcend depression is for you to be open, receptive, and curious about your inner landscape; to be more mindful and intentional in your daily living; and to focus positive energy on the things that matter to you in life. The mindfulness skills that promote psychological flexibility don’t operate in a vacuum; instead, they tend to be interrelated and to support each other. For example, the more open you are to distressing, unwanted internal experiences, the easier it is for you to be present, and to be intentional in your actions. The more mindfully you approach your daily life, the more likely you are to treat yourself and others with compassion. The more you approach and try to solve problems in spite of being in emotional pain, the more you learn that being free from emotional pain is not necessary to feel alive and full of purpose.

This leads us to the three principles of living that will let you transcend depression and radically change your life:

- Spend as much time as you can each day trying to be present. Practice waking up your senses so that you are exquisitely tuned in to what is going inside you and all around you. This is where the joy of living is!

- Be open, curious, and nonjudgmental about your inner experiences, even the hard ones. They can’t harm you unless you get into a struggle with them. You can learn from all of your inner experiences, not just the ones that you like.

- Set up your daily routines to reflect your values. This will give you an active sense that you are living intentionally and behaving with purpose. Even tough life situations can produce growth in you when you respond according to what you believe in.

When you live out these principles on a daily basis, you will begin to notice that your life outlook has improved, that you have more positive emotional experiences, and that you have a distinct sense that it is just easier to be you. In part 2, we are going to teach you nine specific ways you can practice and apply mindfulness skills to create the type of life you have always dreamed of living. If you are intrigued with this prospect—and we would be surprised if you aren’t—then read on!

Ideas to Cultivate

- The mind is a product of the operating system of language and thought. It is not a thing but rather a dynamic, unfolding process that you can observe without getting caught up in it (with training and practice).

- Reactive mind is a built-in rule follower. It can be helpful in some situations, but not in all. Developing a new relationship to your reactive mind is an important step in overcoming depression.

- Wise mind is the ultimate sanctuary from reactive mind. It is a source of peace, tranquility, and compassion for yourself and others.

- Psychological flexibility involves being open, receptive, and observant of distressing emotions (and the thoughts, memories, or sensations that trigger them); being present in the here and now; and engaging in intentional, valued action at the same time. Your goal is to develop greater psychological flexibility in painful moments rather than chase after the holy grail of “happiness.”

- Five unique and interrelated skills contribute to mindfulness, at any given moment. You can strengthen all of these skills with practice.