Some have said that the master (shaykh) must be able to eat the disciple (murid) and that a master who is not like this has not reached mastery. This ‘eating the disciple’ means the master must be able to work on the interior (batin) of the disciple. He must be able to eat up his blameworthy habits—meaning annihilate them—and establish praiseworthy habits in their place. He must be capable of taking him to the level of [God’s] presence (huzur) and awareness (agahi).

—SAFI, RASHAHAT

Observed externally, Sufism may fairly be compared to a game of hide-and-seek. To the extent that such a generalization is possible, the history of Sufism represents a particular, longstanding evolution of thought and practice around the idea that the world has apparent or exterior (

zahir), and hidden or interior (

batin) aspects. In Sufi discourse the interior world is valorized above the exterior, and seeking experiences in the interior is the overarching object of Sufi discussions and the ultimate goal of Sufi practice. There is, however, no way to get to the interior save through external surfaces: knowledge of the interior is predicated on the ability to understand and interpret the exterior correctly. Consequently, what we see in Sufi literature is not a world divided neatly between the interior and the exterior, but the record of transactions across the line that separates these foundational categories. Powerful masters can reach into disciples’ nonmaterial interiors to “eat up” the latter’s habits, which pertain to behaviors in the material world. And disciples wishing to reach stations of knowledge and experience within the interior need masters available in the flesh to intrude on fundamental aspects of their beings. The working of these processes intertwines the interiors and exteriors of masters and disciples in multiple ways. The rich social worlds inhabited by Sufi actors we see narrated in Sufi texts are products of this intertwining that is rooted in particular ways of imagining the place of human beings within the cosmos.

1

In the Sufi context it is useful to consider human bodies as doorways that connect the exterior and interior aspects of reality. In material terms, bodies are objects like any other, subject to generation and corruption and enmeshed in relationships with other material forms of the apparent realm. But bodies are also the instruments that enable human beings to attempt the critical work of excavating through materiality to the interior. Sufi attention to the structure of the human body as a form reflects particular cognizance of the body’s double meaning: on one side, the body is seen as the ultimate source of most problems since its instinctive appetites restrict human beings from thinking beyond their immediate desires; on the other side, the body is a vital venue for theorization and investigation because it enables human beings to transcend materiality. The contrast between the two functions endows the body with a thoroughgoing ambiguity that makes corporeality an advantageous lens through which to appraise Sufi ideas and social patterns.

My reading of the extensive collection of sources on which this book is based indicates that Sufi thought and practice in the Persianate context are too heterogeneous to yield a coherent theory of corporeality. Consequently, we must think of the body in this context as an entity suspended in a kind of matrix consisting of varying but interrelated meanings that can be substantiated by surveying the material. My aim in this chapter is to provide an overall skeletal map of this matrix through strategic soundings of literature produced during the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries. I deliberately juxtapose opposing viewpoints in order to keep the heterogeneity of the material in the foreground. The topics I highlight are meant to provide a sense for the intellectual conditioning of the authors whose works are my sources for the book. Presenting this material at the outset offers background information for understanding Sufis’ corporeal performances in the socioreligious sphere in Persianate societies. Although the sources I discuss in this chapter pertain to the specific time period that is my focus, the overall tenor of the discussion here is ahistorical since my aim is to lay out the intellectual groundwork for understanding Sufi performances rather than to get into historical specifics.

The chapter has three main sections, each of which highlights a different signification of the apparent-hidden dichotomy in considering Sufi views on corporeality. The first section addresses Sufi understanding of the formation of the human body within the womb as an embryo. The emergence of one body from the interior of another implicates the interior and exterior worlds in multiple ways. The event is seen, simultaneously, as the birth of an animal and the coming into being of a microcosm formed in the image of cosmos.

The second section concentrates on the connection between the body and ruh or spirit, the entity seen as the body’s animating force. Ideas regarding the two entities show them to be thoroughly interdependent, including notions of spiritual bodies that can experience the internal world through the intermediacy of a place designated the realm of images (ʿalam-i misal). While most Persianate Sufis regarded each body to have one spirit attached to it, some allowed the possibility of multiple spirits pouring into bodies of extraordinary human beings such as prophets and Sufi adepts. This section also includes a discussion of the self (nafs), considered the representation of the human will that was thought to be driven by material desires under most circumstances.

The third section considers, first, the heart (Persian dil, Arabic qalb, used interchangeably), the highest organ within the body that enables human beings to sense and experience realities pertaining to the interior world. This is followed by Sufi understanding of the science of physiognomy that indicated that human beings are predetermined to behave in certain ways based on characteristics involving the shapes, sizes, and colors of their bodies’ observable parts. But the Sufi view of physiognomy also affirms the idea that individuals can overcome the characteristics inherent in their bodies through expending effort under the guidance of those whose bodies are already endowed with higher and more praiseworthy capacities.

As seen in the cases I discuss, the Sufi imagination of the body portrays it as the primary conjoiner of physical and metaphysical aspects of existence. Similarly, even in theoretical discussions, the body also consistently engages social aspects, showing that Sufis’ investment in the idea of the interior did not free them from paying careful attention to the construction of the material world in all its various dimensions. The Sufi social world was predicated on dividing both persons and the cosmos at large into exteriors and interiors, with all different components overlapping and interpenetrating in a plethora of ways.

BODY WITHIN A BODY: THE HUMAN EMBRYO

It is reported that the famous Sufi master and poet Shah Qasim-i Anvar (d. 1433), whom I will mention a number of times in this book, was once asked whether the source of humanity’s nobility was the physical form of Adam, the first human being, or his internal nature. He replied that it was the combination of the two, “neither solely the form nor the [internal] meaning by itself. His composite being is the locus of manifestation of the whole cosmos and the place where all divine qualities can arise. Whoever can be described in such a way is noble. If we say that the nobility of the human species is because of its internal meaning, it is only because this meaning refers to his sacred spirit (

ruh), which is the closest thing to God, the great, the most exalted. And whatever is closest to God is the most honorable and noble among all that God has created.”

2 This statement specifies the significance of the body within the understanding of the composite human being that can be substantiated further by considering understandings of the human embryo.

Sufi discussions of the generation and maturation of the human embryo in the womb derive from hints found in the Quran as well as understandings of human life absorbed into Islamic thought from Hellenistic metaphysical and medical discourses that went into the formation of the medieval Islamic intellectual tradition. The Quran provides a rudimentary vocabulary for the generation of the human body by talking about phases in which male and female fluids intermix inside the womb to produce an object that passes through the stages of being sperm (

nutfa), blood clot (

ʿalaqa), and morsel (

mudgha).

3 Most Muslim religious scholars and physicians in the medieval period adhered to the idea that human generation involved equal participation from the male and the female, a theory that was ratified also by the Galenic medical system inherited from late antiquity.

4 The fetus’s development through the three stages was pegged at forty days each on the basis of both hadith and medical reports; a survey of Islamic works suggests that medieval Muslims were generally able to correlate prophetic statements with Galenic medical concepts remarkably successfully on the question of human generation.

5Persianate understandings of the embryo from the period that concerns me follow from earlier medical traditions, as exemplified in the popular work

Tashrih-i Mansuri, composed around 1396. This work survives in numerous manuscripts that are notable for including four or five detailed diagrams of the body, one of which illustrates a pregnant woman. The work begins its presentation of the body by citing the Sufi maxim “whoever knows himself knows his lord” to justify its subject, indicating the wide circulation of Sufi ideas in this period.

6 Beyond these references, this work is a standard medical text not of direct interest for the present study. Sufi authors who discuss the embryo repeat the developmental program found in standard Islamic medical works but with added metaphysical elements related to Sufi cosmology. A detailed example for this is to be found in the Mafatih al-i

Mafatih al-iʿ jaz fi sharh-i Gulshan-i raz (

Miraculous Keys for Explaining The Secret Garden) by Shams ad-Din Lahiji (d. 1506–1507) written circa 1477. This work—an extended commentary on Mahmud Shabistari’s (d. 1317) narrative poem

The Secret Garden (

Gulshan-i raz)—was a widely popular text for teaching Sufi basics to new disciples.

7Lahiji writes that when the sperm settles in the womb it produces a spherical entity filled with a creamy liquid. The natural force that generates form acts within this liquid, first turning it foamy and then causing the appearance of three dots that are the places where the heart, the liver, and the brain will eventually come to be situated. Then appears the place for the navel, and the whole organism becomes enveloped in a thin membrane. Some of the liquid within the membrane turns to blood, the navel takes shape, and the whole organism turns into a blood clot. This blood clot then turns into a morsel (

mudgha), within which the major organs of the body acquire their specific shapes. This is followed by the appearance of bones, the separation of various organs from each other, and the establishment of powers particular to various parts of the body. Each of these processes spans a set number of days within the gestational period. The embryo is completed and ready for the spirit (

ruh) at 120 days, which now enters and quickens the body. At this point, the fetus becomes fully human and is distinguishable from other animals. Fetal development then continues with the hardening of the bones, the accumulation of flesh on joints, and the formation of facial features and the organs that contain the senses.

8

1.1 Anatomical diagram of a pregnant woman from a copy of Mansur b. Muhammad’s Tashrih-i badan-i insan. Isfahan, Iran, 894 AH/1488 CE. National Library of Medicine, Bethesda, Maryland, MS. P 18, fol. 39b.

Sufis such as Lahiji utilized medical texts for their understanding of the formation of the physical body, but they also went beyond this to delineate the relationship between the formation of the fetus and the cosmos. Doing this underscored the point that the generation of each human being was not merely the coming into being of an animal but the production anew of all the possibilities of the cosmos. Lahiji writes that in each of the first seven months of fetal development the new being is under the influence of a different heavenly sphere. During conception and the first month, the fetus takes effect from Saturn, and so it continues every month with the successive ascendancy of Jupiter, Mars, the sun, Venus, Mercury, and the moon. The child has a good chance of survival if it is delivered in the seventh month because the moon is “hot” and “wet” in terms of the humors that govern the material cosmos. This is so because heat and wetness indicate life. The chance of survival goes down in the eighth month because the cycle starts again with Saturn, which is cold and dry and is antithetical to life. The fetus is under the influence of Jupiter in the ninth month and has the best chance of survival because this planet is also hot and wet and supports life.

9 The correlations Lahiji draws between the development of the fetus and the heavenly spheres reflect the significance of astrology in the medieval Islamic world. The spheres are constantly acting upon the world, most particularly by influencing human affairs on both the individual as well as the social levels. Their connection to the development of the embryo underscores the link between human life and the structure of the cosmos.

A sustained description of the development of the embryo as the replication of cosmogony is provided in the thought of the Sufi-inspired Hurufi sect founded on the ideas of Fazlallah Astarabadi (d. 1394). Hurufi views cannot be taken as the standard for all Persianate Sufis but they are instructive inasmuch as they represent the radicalization of common notions.

10 The author of a short anonymous Hurufi treatise states that the two ultimate created entities in the cosmos are the Quran and the human body, both of which have seven levels. For the textual Quran, this means that seven different internal meanings can be ascribed to each verse. And for the body, the seven levels can be seen in the way the embryo is generated and matures in seven steps.

The first step in the process is the transfer of the male sperm into the female womb, which this author portrays, on the basis of Arabic morphology, as a transaction between the exterior and interior worlds. The man’s sperm is said to reside in his back (

zahr) and its receptor is the woman’s stomach (

batn). The word

zahr is from the same root as

zahir, the exterior world, while

batn is connected to

batin, the interior world. Following inception, the fetus matures, hidden from direct observation, in the mother’s womb by going through more stages: it becomes 2. a blood clot, then turns into 3. a lump of flesh, then successively acquires 4. bones and 5. flesh, and eventually becomes imprinted with the 6. seven facial lines that the Hurufis thought were the hallmark of the human species. The seven lines, which represent the presence of a sevenfold cycle within the overarching embryonic cycle, are the hairline on the forehead, the two eyebrows, and the set of four eyelashes. The seventh and last step in the completion of the human being occurs when God blows his spirit into the completed body. The overall cycle is directly comparable to the production of the cosmos when God created Adam on the seventh day after creating the rest of the world.

11The Hurufis were particularly invested in rationalizing all aspects of existence into systems that could be put adjacent to each other to show the mathematically consistent nature of the cosmos. Their understanding of human generation is a direct reflection of this approach, and one of its most interesting features is the idea that the generation of the human body is a transaction between the exterior and interior aspects of existence. In their view of the embryo, the possibility of crossing the interior-exterior boundary is inherent in the very process through which human bodies acquire their material shape. Accessing interior knowledge as a fully functioning human being in later life is a kind of recovery of the body’s own preexistence and past. To do so requires “reading” the body from its skin inward, much the same way as one may begin with the literal sense of Quranic verses and then probe deeper to get to higher, interior meanings.

12The understandings of the embryo I have presented show human physiology to be a matter intertwined with the social realm as well as the cosmos as a whole. The birth of a new human being requires the relationship between a man and woman, and the product of their union reenacts the cosmogonic drama. It is no surprise, then, that the human body is not comparable to ordinary material objects or even the bodies of other animals. From its moment of inception to full maturation, the physical body is enmeshed in social and cosmological relations that stick to it like strings attached to a puppet. To understand Sufi views of the full body requires scrutinizing matters beyond mere flesh and bone.

13EMBODIED SPIRITS AND SPIRITUAL BODIES

We have already been introduced to the “spirit” (ruh), the animating principle that becomes attached to the embryonic body at a particular point during its development. The spirit is an essential concomitant of the living human body, although the combining of the two raises a number of questions on which we can find varying views. These include: how do the two bond to each other? Do both have the capacity to influence each other and, if so, how? And what happens to the spirit when the relationship is severed? These issues find mention in Persianate Sufi theoretical speculation as well as in descriptions of religious experiences.

Khwaja Muhammad Parsa’s work Fasl al-khitab (The Decisive Speech), whose title refers to a Quranic verse (38:20), is an extensive compendium of discussions on Sufi topics presented with copious citations from classical Sufi works. For many centuries this work was a staple of educational curricula, particularly in Central Asia. On the issue of the spirit, Parsa writes:

The togetherness between the spirit (

ruh) and the body (

jasad) is akin to the togetherness between the Truth—may He be praised—and the whole created universe. … In the words of some people of knowledge (

ʿurafaʾ)—may God have mercy on them—the human body is composed of four opposing elements: earth, wind, water, and fire. These four exist in a truly combined state in the body. The place of the earth in the body is obvious and evident; water has a place within earth, subtle and appropriate for the subtlety of water; wind has a place within water, more subtle than the place of water; and fire has a place within wind that is more subtle than that of wind. The spirit is truly present in every atom of the body but without being contained in a particular place. Containment and transfer are accidentals related to bodies, none of which can be applied to the spirit.

14

This description attributes distinctive properties to material and nonmaterial elements on the question of the formation of mixtures. The four material elements are nested into each other on the basis of a perceived hierarchy, while the nonmaterial spirit is capable of impregnating everything without being subordinated to anything else. Moreover, the spirit is shown to retain a separate identity despite being present in all atoms of the material entity. These ideas emphasize the spirit’s quality as an “essence” not subject to any notion of confinement in space or accretion of accidental qualities. The spirit is, nevertheless, portrayed as an entity, which requires further consideration of the type of relationship it maintains with the body.

15Some Persianate Sufi authors portray the spirit as a being incarcerated in the prison of the body as a part of God’s larger plan behind the creation of the human species. An illustration for such an understanding comes from the hagiography of Amin ad-Din Balyani (d. 1334), a Sufi master who spent most of his life in Shiraz in southern Iran. The hagiographer purports to convey the master’s own words when describing the body as a prison necessary for the spirit’s self-realization:

The wisdom behind imprisoning the spirit (

ruh) within existence (

wujud) is this: When the spirit came forth in the original world (

ʿalam-i asli), it had no veil. It had come forth within the blessing of union [with God] (

visal) and did not know the value of this blessing. It flew around in the desert of nonexistence, free of pain and sorrow, peaceable and uninhibited. It was unacquainted with tasting and desire, affection and love, and all the stations and degrees. It had no sense for witnessing itself. It needed a mirror in which to witness its own beauty and a secluded place where it could do spiritual exercises and acquire perfection. The heart was made its mirror and the body was made its seclusionary chamber. Then it was turned from the world of union to that of separation so that pain and sorrow, and love and desire, come forth in it. … Then [the expectation was that] it would shun this world, have no regard for anyone, become a seeker after its point of return and true end, and enter the state of servanthood. Then whenever it would reach a new station among the stations of this path it would reach a fresh light and [eventually] attain perfection through this journey.

16

This description emphasizes that the spirit must endeavor to overcome its bodily prison. However, Balyani’s views are not so much a condemnation of the body as a plea for it to be seen in appropriate perspective. In a different place in the same work, Balyani is made to say that the reason human beings are fearful of death is that they think of themselves as bodies and nothing else. They see that, when bodies die, those who are still living find them detestable and worthy of avoidance, which is why they bury them in the earth. Such people fail to recognize that death actually pertains to the jail cell that is the body and not to their life’s principle. The spirit, while it is attached to the body, should be seen as being half-dead; when the body dies, it is released and acquires a new life upon its return to God, as envisioned in God’s plan from the beginning.

17 In ideas attributed to Balyani, the body has a kind of passive agency, rooted in its material nature, which the spirit has to overcome. Its qualities are like an impartial examination that the spirit has to sit for in order to reach salvation. It is not that the body is evil or incites to anything by itself, but that it is the essential obstruction that provides the spirit the opportunity to redeem itself through effort.

Another perspective on the spirit’s existence together with the body uses food as a metaphor to differentiate between the two entities. In a treatise devoted to the Sufi path, the master ʿAli Hamadani writes:

Know that the Truth—may He be praised and exalted—has created the human being from two different essences: a subtle, light-filled essence that is called the spirit, and a dense, dark essence that is called the body. Each one of these essences has a diet and its own types of health, illness, and medicine for the illness. The body’s food are delicacies and water, and that of the spirit and heart are recollection, love, and knowledge of the Truth. The indication of illness in both essences is that, contrary to their natures, their diets become abhorrent to them.

18

He then goes on to explain that, in the case of the body, the lack of appetite must be cured through medicines appropriate for particular cases that rebalance the elements within and expel corrupting materials. Similarly, diseased spirit are in such states that they have either stopped responding to their purpose of inclining toward God or are doing so only in name for the sake of externalities. Different spiritual illnesses have different causes and remedies in the form of “penances and various species of remembrances and worshipful acts whose realities are known only to religious doctors such as prophets, God’s friends, masters of the path, and religious scholars.”

19 This understanding takes us to the social realm so that the fate of both the body and the spirit appear connected to relationships between human beings along with those between humans and God.

The words of the Naqshbandi master Khwaja Ahrar as reported in a hagiography further crystallize how one might see the connection between the spirit and the body as a critical intermediary link connecting a chain of entities spread in the cosmos. Ahrar is shown to say: “The tongue is the mirror of the heart, the heart that of the spirit, the spirit that of the true reality of humanity (

haqiqat-i insani), and this reality that of Truth, may he be praised. Hidden truths travel a long distance from the absolutely hidden essence [i.e., God] to arrive at the tongue. Here they acquire verbal forms and then reach the true ears of those who are prepared.”

20 This description makes elements of the human body such as heart and tongue into critical filters for the conduction of divine truths into the material realm. The spirit is, then, the entity that both endows the body with life and makes it into a divine agent active in the material sphere. Although attached to a particular body, each spirit connects to God via the interior realm on one side and to other human beings through what it can induce into the heart and tongue in the exterior realm on the other. The possible connection between one person’s tongue and another’s ears constitutes the grounds on which multiple bodies and spirits can communicate across their own boundaries.

Spiritual Bodies

I have so far provided examples of how Persianate Sufis considered the question of the spirit’s impact on the material body. The articulation of the relationship between the two entities provides evidence for my suggestion that Sufis saw the body as a critical doorway between the interior and exterior realms. In this context, one can ask if the spirit could be colored by the body as much as the other way around.

The answer to this question leads to the Sufi notion of a special realm termed the imaginal world (

ʿalam-i misal) that is perceived to be situated in between the world of bodies and spirits. As we will see extensively in this book, much of Persianate Sufi literature that describes the inner states of Sufi adepts who follow the prescribed path to become subjects of extraordinary experiences does so in distinctively corporeal terms. Such descriptions are most often a function of alternative states of consciousness, like dreams and visions, in which the subject is presumed to travel inside this imaginal world that is distinguished by the fact that it has no material existence but contains forms in the images of material bodies. The imaginal world is, therefore,

corporeous rather than

corporeal since it can be described in the language of everyday experience, but without the kind of limitations that impinge on action in the material sphere.

21 In Persianate Sufi descriptions, experience in the imaginal world is predicated on the presumed existence of an imaginal or corporeous body that is formed in the image of the physical body. Such a body is necessitated by the fact that describing experience requires the implicit presence of an experiencing body, although the actual physical body cannot have any access to the imaginal sphere. This idea is best understood through examples.

Amin ad-Din Balyani’s hagiographer relates that a man came to the master one day to ask the following:

“I have heard two different things from different elders. One says that the spirit has a form like that of the body, meaning that it has hands, feet, eyes, and ears, and that it has a food and a drink. The other says that the spirit has no form, and it is free from eating and drinking. What do you say about these two opinions?” The master—may God preserve his secret—said: “The first statement is believable in that the spirit has a form, but this is a spiritual one (

ruhani) and its food and drink are also spiritual.” When that man had left, he said, “Once I saw in a vision that I had reached the end of time and my spirit had become detached from my body, which was lying there dead, and I was standing on my feet in the same form that I have now. I observed this body to note that it had hands, feet, eyes, ears, and all the other organs. But these were all spiritual so that when I lifted a hand to grasp one of the other organs, it could grasp nothing and was itself made of spirit.”

22

The type of spiritual body Balyani is describing is presumed in Persianate Sufi literature without extended theorization. To see how it could be understood in theoretical terms, we can consider briefly the writings of Ibn al-

ʿArabi, the prominent Sufi philosopher and theoretician whose ideas greatly influenced Persianate Sufi thought. Ibn al-

ʿArabi presents the corporeous body as an exact nonmaterial counterpart tethered to the physical body. This body cannot be apprehended by the five physical human senses; however, it does have definite reality to it, which is felt during dreams and visions. These experiences are not mere mental projections but real encounters with other corporeous rather than corporeal bodies. The corporeous body is tethered to the physical body as long as the latter is alive, although it is liable to drift away when a person is unconscious as during sleep or in a trance. The tether is severed when the corporeal body dies, and all that is left is the corporeous body attached to the spirit. These two entities continue to exist together until the promised resurrection from death at the end of time. Then God provides another corporeal body for the spirit so that the afterlife is experienced physically. Human beings are resurrected in material bodies, though these are not the same as their original bodies. However, a kind of impression of the original physical body in the form of the corporeous body sticks with the spirit throughout its existence.

23Not all Persianate Sufis may have agreed with the details of the perspectives of Balyani and Ibn al-ʿArabi that I have cited, but the general principle at the base of these views appears to have been common coin in Sufi thought and practice. Dreams and visions were major venues for encountering heavenly beings as well as judging one’s progress on the Sufi path, and the corporeous body (or an idea akin to it) allowed Sufis to express their experiences in concrete rather than abstract terms. The corporeous body had its own set of senses that enabled it to see, hear, touch, taste, and smell other corporeous bodies in the imaginal world. Just as the physical body and its senses made it possible to apprehend the material cosmos, the corporeous body and its senses made the imaginal world an existent reality that could be experienced and described in language.

In most descriptions of Sufi experiences, the material and imaginal worlds, and the respective bodies that can sense these, remain separate. This is exemplified in views of the author of a hagiographic narrative dedicated to

ʿAli Hamadani who states that the transition between the two types of senses—corporeal and imaginal—is what causes one to have an odd bodily feeling upon waking up. In this liminal moment some impulses from the alternative corporeous senses coexist together with physical sensations generated by the ordinary senses, although the feeling passes when one is fully awake or asleep.

24 We have an instance that shows interaction between the two bodies of a single person in the hagiography of the rural Central Asian master Shaykh Sayyid Ahmad Bashiri (d. ca. 1461–62). The author of this work relates from the master himself that one day, when he was traveling in the early morning, he saw a bodily form that looked like himself standing at a distance. As he approached this being he felt that he was getting away from himself and, by the time he reached it, he had completely lost all sense of his physical body and had become one with this body, which felt as if it was made of light. This event was a memorable experience for Shaykh Bashiri, and every time he related it he pondered over it and was filled with the joy he had felt at the original occasion. The hagiographer states that the body Shaykh Bashiri experienced was what Sufis call the acquired body (

badan-i muktasab) or a type of being that is a gift from God (

vujud-i mawhub-i haqqani). The acquisition of this body was to be understood as a second birth, which provides one the ability to experience the higher, nonmaterial world that is hidden from the senses of the material body.

25This understanding of the second body is different than what is suggested in works by Ibn al-ʿArabi’s and others since it comes into existence as a result of spiritual endeavor instead of being present with the corporeal body by definition. But the eventual import of the formulation is the same in both cases since the purpose of the second body is to make the imaginal world available to humans. What Farghanaʾi calls the acquisition of the second body amounts, in others’ terms, to an acquisition of the realization that one has such a body attached to the physical body. However one understands its origin, the corporeous body helps one to escape the limitations of the material world and allows one to describe the nonmaterial world in ways that are understandable in the vocabulary of normal human existence. In the end, human beings’ religious status is indexed to their ability to experience the unseen world through their corporeous bodies and to relate these experiences to others through exercising the powers of the organs of their corporeal bodies. In light of these views, at least those human beings who are capable of fulfilling humanity’s ultimate potential possess corporeal as well corporeous bodies.

Bodies and Spirits Intermingled

Most Persianate Sufis would have agreed with the formulation that human bodies need to be harnessed to reach salvation and that spirits reach their destiny by becoming capable of experiencing the unseen world through the intermediacy of corporeous or acquired bodies. However, in a minority of cases, the privileging of the spirit over the earthly body could be inverted. That is, some Sufis exalted direct action in the physical world above that which could be experienced in the imaginal world. As can be expected, this was the case with individuals invested in salvation through history that unfolded in front of one’s eyes rather than through an escape from ordinary time and space. We find the most elaborate formulations of this view in arguments put forth by Sufi masters who led messianic movements in the fifteenth century.

The most cogent example for this view of the body is presented in the work of Muhammad Nurbakhsh (d. 1464) who proclaimed himself the messiah in 1423 and wrote a messianic confession explaining his views. He argued that the bodies of the elect among prophets and saints can contain multiple spirits simultaneously since the earthly activity that issues from them represents God’s direct action upon the world. Nurbakhsh saw himself as humanity’s savior at the end of time, whose actions were the fulfillment of Islamic messianic prophecies. This claim was difficult to justify in the face of the fact that most Muslims in Nurbakhsh’s time believed that the messiah was an identifiable historical person named Muhammad al-Mahdi who had gone into heavenly hiding in the year 874 in Samarra and was expected to descend to the earth as an adult at the end of time. Nurbakhsh’s solution to this problem was a concept that he called projection (

buruz), according to which the messiah was not a long-lived heavenly figure but someone like himself whose body had came into the world through a normal birth. But, with spiritual maturation, his body had become host to the spirits of Jesus, Muhammad, the expected messiah, and many great Sufi masters of the past. The actions performed by the messiah’s body were thus to be identified with the wishes of the spirits of all great religious leaders from the past. Since he saw himself as the messiah, Nurbakhsh thought that his physical work in the world was an exteriorization of all the spiritual work carried out in the imaginal sphere in previous times. In his view, God had decreed this transfer of salvation from the interior to the exterior world as the mark of the end of time. By this token, Nurbakhsh’s body was the ultimate instrument through which God intended to fulfill the destiny of the cosmos.

26Nurbakhsh’s views are echoed in a different form in the work of Muhammad b. Falah Musha

ʿsha

ʿ (d. 1462) who also declared himself a messianic redeemer based on his claims of being the greatest Sufi master of his age. Instead of the idea of multiple spirits in a single body, Musha

ʿsha

ʿ made a distinction between the essences of particular beings and the material “veils” that made these essences present in the world. He maintained that the earthly bodies of prophets and Shi

ʿi imams—the last of whom was the hidden messiah living in the heavens—had been veils for the presence of God’s essence. He saw his own body as a veil over the veil of the messiah and thought that this last great deliverer can be present in the material world only in the form of such a veil. All that Musha

ʿsha

ʿ did using his own body was to be seen as the activity of the messiah that originated directly in God as the essence situated behind two corporeal veils.

27 As in Nurbakhsh’s case, Musha

ʿsha

ʿ’s formulation subsumed the spirits of others, and even God’s essence, into the activities of his corporeal body. This was the ultimate inversion of the normative pattern since divinity and spiritual entities of the higher spheres were seen to descend into the material sphere rather than spirits imprisoned in material bodies using corporeous bodies to ascend the cosmic hierarchy to reach higher levels.

28

The Self (Nafs)

In addition to the spirit, Sufis and other Muslim authors also employ the term

nafs, which I translate as “self,” to designate a nonmaterial aspect of the human person. The self is sometimes used as a synonym of the spirit, although in the Sufi context it usually comes quite close to what is meant by the term

self in modern psychological understandings.

29 While spirit is thought to be an uncorruptible and indivisible essence that attaches to the body, the self is not an entity but the sum total of a person’s attitude toward the world. The self is, therefore, quite changeable and can even be reduced to nonexistence. Indeed, the major Sufi goal known under the term

fanaʾ, or annihilation, refers to the total decimation of egotistical and concupiscent aspects of a person’s self in favor of an orientation toward God alone.

30The standard medieval Sufi understanding of the self ’s capabilities divides it into three parts as can be seen in the following description by ʿAbd ar-Razzaq Kashani (d. 1330), author of major treatises on the definition of Sufi concepts:

The inciting self: This is the one that commands toward wrong acts; it deceives one into thinking that benefit lies in performing these acts rather than in shunning them.

The censuring self: This is the one that knows, when it nears a sin or an injustice, that benefit lies in shunning [such an act]. It censures itself with respect to such an act but finds arguments against itself rising from within.

Peaceful self: This is the one that finds itself peaceful because it perseveres in acts of obedience—finding no inclination within itself toward abandoning them—and has no desire for sinful acts. This is what is referred to in His saying: “Self at peace, return to your lord; well-pleasing and well-pleased; and enter among my servants and enter my garden (Quran, 89:27–30).” Its entry among the servants—those attached to the [divine] presence—is entry into the group of noble spirits who have been granted intimacy and who “do not disobey God in what he commands them and do what they are commanded” (66:6). This equips the peaceful self with the qualities of those who are cloistered in prayer in the sanctified presence. It [also] endows it with their behavior, which includes remaining untouched by earthly, corporeal enjoyments as well as deviant qualities that characterize the created, materialized world. It separates it from habits that bring to ruin and establishes it in many types of worship that lead to deliverance. With this, it enters the interior (

batin) of the garden, meaning that it breaches the obstruction that obscures [God’s] hidden essence behind the veils of the forms of [his] attributes—as you know. Doing this delivers it from the dress of createdness and affirms it in the quality of true singleness.

31

Kashani’s division of the self into three parts is in fact a categorization of three types of actions the human being is capable of undertaking in the light of religious injunctions. The self at peace in this description appears synonymous with what I have described regarding the Sufi understanding of the spirit. The extended description of the third self implies that the self in general inclines to these functions in inverse proportion to its subservience to the material body, within which it or the spirit are located during a human being’s existence on earth. Here, as elsewhere in Sufi thought, discussion of the self and the spirit presumes a concomitant body whose propensities determine how the self measures up with respect to what it has been commanded to do in religious terms. The self ’s incitement to evil, censuring, or peacefulness are modulated fundamentally by its relationship with the body that is the actual interface between an individual being and the negatively marked material world. Peace in the presence of God’s essence, the Sufi’s ultimate aim, is achieved when the self draws aside the veil that separates the material world from hidden truths. From the perspective of human experience, the most significant manifestation of this veil is the human body itself since this entity instantiates a person as an aspect of the material world. In this understanding, which formed the basis of much of medieval Sufi thought, to become peaceful requires the self to firmly regulate its connection to the body. I will discuss the practical implications of this perspective in the course of analyzing Sufi religious actions in

chapters 2 and

3.

THE BODY’S ORGANS, INSIDE AND OUT

The previous discussion indicates that, for Persianate Sufis, the relationship between the spirit and the body was not simply that between a privileged noble element and a troublesome dense object. During its living condition, the body’s atoms were seen to be permeated with the noble spirit and, conversely, the spirit could be imagined to be corporeous, imprinted with the form of the body due to the association of the two elements. The mutual interpenetration of the spirit and body reflects the intermixing of the interior and exterior elements of reality in Sufi thought; when we scrutinize Sufi literature carefully, the purportedly clear distinction looks more like a scene of shifting sands than a dichotomy.

In this section of

chapter 1 I focus on Persianate Sufi understandings of specific elements of the body that determine its relationships to the interior and exterior worlds. These include the heart, which sits inside the body and is regarded as the noble organ able to experience the interior world. The obverse of that is the external form that constitutes the object of the science of physiognomy. The outer form interfaces with the physical world and is understood as a signifying palette that can be read by others to evaluate the being who inhabits the body. The ensuing discussion further substantiates my suggestion that bodies in Persianate Sufism come across as doorways between the exterior and interior realms.

32

The Perceiving Heart

In Sufi literature the heart is usually discussed not as a physical object but as the organ whose powers and attributes define humans as living, apprehending, and acting beings in the world. In the words of Qasim-i Anvar, the heart within the human being (microcosm) is like the human being within the universe (macrocosm). In both cases the entities inside reflect the most highly valued aspects of the larger beings in question, The human heart can then be said to be the most valued element in the cosmos as a whole.

33We can get a sense for the functions attributed to the heart from an extended taxonomy presented in a widely influential work by Najm ad-Din Razi Daya (d. 1257–58). This work is worth considering for understanding Sufi thought and practice in subsequent centuries since it was widely used as a manual for training and is cited often by later authors. Daya writes, reflecting associations found in prior works, that the “relation of the heart to the microcosm is the same as that of the throne [of God] to the macrocosm. The heart, however, has a property and a nobility that the throne does not possess, for the heart is aware of receiving the effusion of the grace of the spirit, while the throne has no such awareness.”

34 A later author who likens the heart to the throne perceives the issue differently, stating that the sympathy between the two means that they are constantly emitting things toward each other. If one side is stronger, it absorbs the other, which is not desirable. But, if they possess the same intensity, this results in love’s perfection between the two, the ultimate goal.

35 The heart therefore acts as the conduit between God and the human being and is the seat of human life and intellect.

One particularly interesting aspect of Daya’s understanding of the heart (which is repeated verbatim in a significant fourteenth-century Naqshbandi work, among other places) is the idea that the heart is itself a shadow body within the body.

36 It has its own five senses, which mirror the body’s senses, and its correct functioning depends on the health of these senses. Just as the physical senses make the material world available to human consciousness, the heart’s senses bring sensations of the interior world into the heart’s purview: its eyes see the sights of the unseen, its ears hear God’s speech, its nose smells the perfumes of the heavenly realm, its tongue tastes divine love and interior knowledge, and the sense of touch, which is spread all over its exterior, gives a comprehensive experience of the unseen world. Just as the physical senses aggregate together to create a feeling for the body’s presence in the physical realm, so do the heart’s internal senses provide spiritual intelligence. And, just as the correct working of the physical senses makes a person physically capable, the heart’s senses make it possible for the person to travel in the metaphysical realm.

37Daya’s taxonomy of the heart divides it into seven parts: breast (

sadr), heart (

qalb), pericardium (

shaghaf), inner heart (

fuʾad), grain of the heart (

hubbat al-qalb), the black dot (

suvaydaʾ), and the blood of the heart (

muhjat al-qalb). The heart’s sevenfold structure is to be seen as parallel to the seven spheres of heaven so that a descent to the core of the heart is the microcosmic equivalent of an ascent in the macrocosm, both journeys leading eventually to God.

38 Daya’s description of the heart as a body with senses that parallel the senses of the physical body should be reminiscent of the notion of the corporeous or acquired body discussed earlier in this chapter. Both the heart and the corporeous body are shadow images of the physical body, one perceived to be buried inside the chest and the other shown tethered to the outside. The similarity between the two is not coincidental: the conceptualization of these entities reflects the imperative that human experience can be represented only through corporeal metaphors even when it is understood to take place in the metaphysical realm. These Sufi speculations on the heart and the corporeous body constitute fundamental presumptions that make it possible for Sufis to imagine crossing the exterior-interior boundary to experience nonmaterial realms.

Standing outside Sufi metaphysics, we can say that the heart and the corporeous body are nonmaterial images of the physical body that enabled Sufi theorists to expand the body beyond its limits. Getting to the heart did this by diving into the body, to discover that the whole cosmos was within it. This represented a case of exploring the macrocosm through the microcosm. And the corporeous body accomplished the same by equipping the person to fly away from the physical body and roam through the macrocosm. This, then, was a case of making available senses that allowed access to worlds and knowledge that were beyond perception under ordinary circumstances. The centrality of the heart and the corporeous body in Sufi thought underscores the point that for Sufis the imagination of the body far exceeds what can be seen, heard, smelled, tasted, and touched through the body’s physical senses. To concentrate on the Sufi understanding of the body is not simply to explore a physical object but to see how human beings have imagined the cosmos as a reflection of their own beings.

The Readable Body

I have already mentioned the notion that the body can be read from the outside in the context of describing Hurufi views on the development of the human embryo. The principle involved in this instance finds wide application in Persianate Sufi literature, although full-fledged metaphorical interpretations of the body’s various parts as could be observed externally are quite rare.

39 Hurufis are an exception here since they were particularly keen to show the correspondence between text in the Arabic script and the body. One instance of such mapping of the body is the argument that each bodily organ corresponds with a letter of the alphabet on the basis of its shape. Thus, the head is likened to the letter

hay, the ear to

fay, the eye to

zad, the nose to

ta, and the mouth to the

hay again. The body as a whole resembles the combination of two letters

lam-alif, which the Hurufis regarded as a single letter in the Arabic alphabet put there as a stand in for the four letters (

p-

ch-

zh-

g) that have to be added to this alphabet to write Persian.

40 The overall effect of this mapping between the alphabet and the body is, once again, to compel people to think of the form of the body as a kind of text that could be read.

41In medieval Islamic societies, a more mainstream and quite widespread form of “reading” the body than the Hurufi system was the science of physiognomy, known in Persian under the term

firasat. Concerned with divining the moral and other qualities of particular human beings on the basis of physical properties of their external body parts, this science had precedents going back to both pre-Islamic Arabia and Hellenistic traditions of late antiquity. Authors concerned with the science in Persianate societies divide it into two branches based upon what were thought to be the sources of the knowledge. The first branch, which the prominent polymath Fakhr ad-Din Razi (d. 1209) likens to medicine, was predicated on the idea that the optimal human body holds all the elements and humors of nature in perfect equilibrium within itself. All the organs of such a body are exactly proportional to each other, conveying an overwhelmingly pleasant effect on anyone who senses it. Most bodies do not have this perfection and have organs disproportionately large, small, fat, thin, long, or short. The expert in physiognomy knows, on the basis of normal study, how to correlate particular complexions and shapes and sizes of body organs to a person’s natural instincts and habits. For example, such an expert’s knowledge of the literature on physiognomy would indicate the following about eyebrows: “(a) Overly bushy eyebrows indicate that the person is inclined toward sadness and brooding. This is so because hair is formed of a smoky matter, and the abundance of hair on the eyebrows indicates an excess of such matter in the cranium. This, in turn, points to the predominance of black bile from among the natural humors, which produces sorrow and anxiety. (b) If the eyebrows are long, extending toward the temples, then the person is arrogant and pompous. (c) Someone whose eyebrows incline downward on the nose side and upward near the temples is arrogant and foolish.”

42In addition to this kind of straightforward observation of corporeal features that led to knowledge of a person, Razi mentions that great prophets and friends of God have the ability to read bodies and bodily behavior since they possess intuitive knowledge.

43 The basis for such intuitive physiognomy is described in a work by the prominent Naqshbandi shaykh and prolific author Khwaja Muhammad Parsa. He writes that perfected friends of God are able to see the light of the true, interior world, which is the underlying nature of all human beings but is, among ordinary humans, hidden from view because of the denseness of natural elements and human nature. Friends’ complete access to this light means that they can, through physiognomic interpretation, know the “inner states, abilities, thoughts, intentions, and hidden acts and situations of all people. They apprehend these hidden matters through studying their physical states and bodily organs. With this same light of true life—which is the light of God—they enliven the hearts of disciples who are prepared.”

44 This type of physiognomy could not be learned from books and resulted from the physiognomist’s access to the interior world. As we will see in many discussions later in this book, visual inspection is represented as being a major tool in the hands of masters to decipher the spiritual states of their disciples and indicate the correct path they need to follow.

In literature produced during the fifteenth century, Muhammad Nurbakhsh’s popular treatise on physiognomy repeats the arguments found in earlier works, but also ties the science directly to Sufi religious aims. Nurbakhsh represents physiognomy as a highly useful science, even though it ranks lower than the knowledge gained from revelation and mystical unveiling (

mukashafa), which is limited to prophets and God’s friends, and the sciences of astrology and numerology practiced by philosophers (

hukamaʾ).

45 His justifications for its validity include statements from Muhammad as well as the observation that if the characteristics of various species of animals can be understood from observing them externally the same should be possible for humans who represent the aggregation of all possibilities of living beings into a single species.

46As in the case of Razi’s treatise, Nurbakhsh provides specific interpretations of the sizes, colors, and shapes of different bodily organs, placing particular emphasis on the eyes. More interestingly, he then goes on to acknowledge that it is quite possible to have a composite body whose various organs signify opposite characteristics. In such cases the interpreter must follow the rules of basic mathematics. For example, if two organs suggest intelligence and one stupidity, the person ought to be considered intelligent.

47 Moreover, properties associated with bodily organs can be overcome through deliberate effort and the company of the religious elect. He exemplifies this principle through a story about Plato, who purportedly sent some students to India to visit a philosopher. The Indian philosopher asked the students to describe Plato to him, and, when they did, he proceeded to list all the negative attributes obvious from his appearance. When the students got back to Plato, they declared the Indian philosopher to have been an ignoramus. However, when they told Plato what he had said, the Greek philosopher said that he had been right in identifying those negative characteristics as part of his nature. However, Plato argued, the philosopher had failed to realize that he had overcome these physical attributes through hard work.

48The story about Plato shows that physiology need not be regarded as a prison for human beings, even though it acknowledges that all bodies are born with particular propensities inherent in their physical constitutions. Sufi intellectual and social programs covered in detail in later chapters take this view for granted. They recognize the body’s agency as an actor by itself, but they also insist that Sufi prescriptions are aimed at maximizing its positive characteristics and suppressing the negatives on an individual basis.

Overlapping Bodies

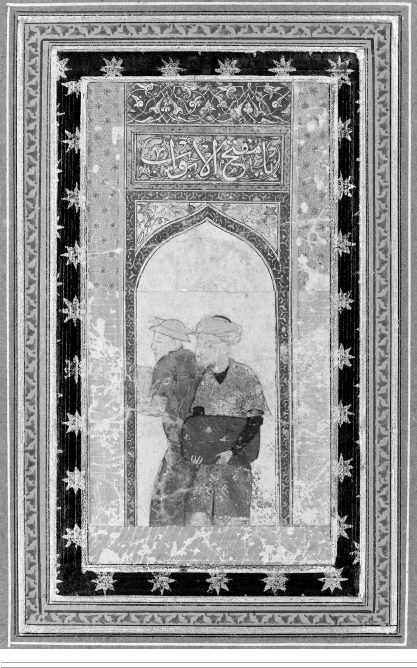

A miniature painting dating to the early sixteenth century shows the figures of two Sufi men framed by a doorway with the inscription “O you who opens doors.”

49 The doorway—pictorial as well as textual—can be read as referring to the point of access between the interior and the exterior realms. The verbal invocation seems to address two beings: God, who may allow one to access higher truths, and the Sufi master, whose teaching and training enables one to see and walk through the doorway. The two men’s heads are drawn as separate, and are distinguished from each other on the basis of facial hair and headdress. Their postures suggest that one is entering the doorway while the other hesitates before following him or leaving the scene. The bodies overlap; whether they would continue to do so beyond the pictured instant depends on the moment of decision encapsulated in the scene.

This is an admittedly speculative reading of the image, one that reflects our lack of information about the painter’s intentions. But it is useful to think of this image in conjunction with what I have argued regarding Sufi representations of the body in this chapter. If the human body can be regarded as a doorway between the interior and the exterior, the decorated portal looming over the human forms adds to the body’s status as an object that encapsulates liminality and transition. Critically, the scene in the painting presents two overlapping bodies rather than a solitary figure negotiating the doorway.

1.2 The entry into the grave. Persian, Safavid period, early sixteenth century, Iran. Opaque watercolor and ink on paper, possibly a manuscript page, 7.4 × 3.6 cm. Photograph copyright © 2010 Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. Francis Bartlett Donation of 1912 and Picture Fund 14.572.

The togetherness of the two bodies as depicted in this painting is a significant feature of the theoretical discourses I have presented in this chapter. Although each particular human being is thought to have a body and spirit, the pair never exists in strict isolation. The body and spirit of each person are connected to other bodies and spirits, across all boundaries that define the person as a discrete entity. Similarly, the multitiered heart requires the guidance of a master to realize its functions, and particular bodies’ physiognomic handicaps can also be overcome through one’s affiliation with a master. The bodies of such masters are open doorways to the interior world, a status they acquire through instruction under their own masters. For a Sufi novice, the aim is to transform one’s body from a closed to an open doorway that connects the interior and exterior worlds. As indicated in the quotation from Khwaja Ahrar with which I began the chapter, masters can eat up disciples by allowing the bodies of seekers to enter their own. The theoretical perspectives on corporeality I have discussed in this chapter provide a map for the stage on which dramas of interactions between masters and disciples get played out in Sufi hagiographic works. The remainder of this book is dedicated to discussing the narratives of the dramas themselves.