2.

New Consumer, New Consumer Journey

Marketers have argued for more than a decade about how to bridge the gap between digital natives (people born after 1995) and digital immigrants (older generations forced to migrate to digital from an analog world). Those terms, coined by Mark Prensky in 2001,1 have mostly been replaced with millennials versus Gen-Xers and boomers, but the marketing debates continue just the same.

In the infinite media era, however, those distinctions aren’t relevant, not when it comes to how we motivate consumers. Similarly, the difference between B2B and B2C marketing has completely dropped away. Why? Because “the medium is the message,” as Marshall McLuhan put it.2 His idea, published decades before the dawn of digital, has been interpreted in a variety of ways. But to use McLuhan’s own words, it is the environment that changes people, not the technology.3

In other words, environments are so powerful, they affect all aspects of life, society as well as individuals. McLuhan went so far as to say that the idea we have of romantic love is nothing more than a by-product of the print media. So it isn’t such a reach to think that our idea of marketing is simply a by-product of the limited media era environment. And the rules that applied in that environment—such as distinctions among generations or between types of buyers—no longer hold water today. Our environment changed and so did all of us.

This chapter explores the consumer’s new decision-making process and illuminates how we as brands must respond: with modern methods of reaching and motivating consumers.

The New Consumer Transcends Labels

In 2018 new research revealed that virtually all consumers discover products, evaluate them, purchase them, and want them serviced in similar ways, regardless of the individual’s age, demographic, or business vertical.4 This is a new reality that we marketers must adapt to, all while meeting the expectations of a changed consumer whose decision-making process is radically altered because of the infinite environment (as McLuhan foretold).

Old Dogs, New Tricks

Many people misinterpreted Mark Prensky’s distinction between digital natives and immigrants as “you can’t teach an old dog new tricks.” But that wasn’t his point at all. His goal was to help educational institutions better understand their pupils, whose brains had developed differently because of early exposure to the digital world.

But today we know that the human brain, even older brains, adapts quite quickly to the digital environment. Gary Small, a professor of psychiatry at UCLA and director of its Memory and Aging Center, studied the brain functions of a group of “digital savvy” and “digital naive” subjects as they engaged with modern media, and he discovered just how rapidly this adaptation takes place. Small ran two tests, one to set a baseline for each group and one to test the effect of environment exposure on the digitally naive. He asked the naive group to spend one hour a day online for five days, then return to do the test again. After the second test, Small found that “the exact same neural circuitry in the front part of the brain became active in the internet-naïve subjects.5 Five hours on the internet, and the naïve subjects had already rewired their brain,” in line with the digitally savvy.

So as marketers, we must account for the effects of the media environment on all individuals, because individuals all operate similarly within the infinite environment. Segmenting by age or any other demographic will not help you break through to the modern buyer. This is true whether they are millennials or boomers, even the elderly. My grandfather isn’t shopping on Amazon, but he’s aware of the power of the new environment, so he asks me to check prices for him and make purchases. He has essentially adapted to the infinite media era, and he’s never been on the internet—yet.

A more helpful distinction than a person’s age comes from researchers David S. White and Alison Le Cornu. Their paper “Visitors and Residents: A New Typology for Online Engagement” offers a more behavior-oriented definition of consumers that isn’t tied to generation. Rather than binary opposition, they see consumer behavior as a continuum. At one end are “Visitors,” people who hop on and off the internet, using it primarily as a toolbox. At the other end are “Residents,” who view the internet as a “place” where they interact with clusters of other people “whom they can approach and with whom they can share information about their life and work.”6

Today’s consumers lie somewhere on this continuum, and people formerly viewed as digital immigrants, or boomers, are engaging with the infinite media environment specifically to change their behavior, because they see the benefits it provides. According to our 2017 Salesforce study (State of the Connected Customer) looking at 7,037 global consumers, 72 percent of baby boomers strongly agree that new technology keeps them better informed about product choices than ever before.7 The study also confirms that while there are differences between millennials and other demographic groups regarding expectations, actions, and other factors, the delta between groups is much smaller than traditionally thought. Only a 12 percent gap separated the responses between millennials and baby boomers across the one hundred questions we asked, such as: How willing are you to share personal data for better experiences? How does branded communications in the form of rewards affect your brand loyalty? How important is it to be able to do a price comparison from your mobile device? In short, across the board, our data suggests that if 100 percent of millennials act in a particular way, it’s a good bet that 88 percent of baby boomers do too.

Such rapid adoption by all consumers makes sense when you consider the timeline of past media. The written word took millennia to spread; the printing press took centuries. But by the time we reached the introduction of television, it took only sixty-six years for TV sets to saturate 74 percent of US homes.10 The next major technological advance, the internet, grew to mass adoption (75%) in thirty years, roughly half the time it took television to reach that point. Finally, social media arrived and was adopted by 74 percent of the population in fourteen years. Messaging applications like Facebook Messenger, WhatsApp, WeChat, and LinkedIn Messenger have already overtaken social media in terms of total use, rising to mass adoption in less than seven years. So what’s next? Chatbots have now entered the scene, and 80 percent of US businesses expect to use them by 2020.11 Augmented reality (AR) was added to iPhone and Android operating systems in 2018,12 so following the same trajectory, we should expect highly immersive AR experiences to be mainstream with all consumers by the mid-2020s. Not only is new media technology adopted in half the time of whatever its predecessor happened to be, but with the shorter intervals between the introduction of new media, the halving is accelerating too. (For more on what all of this implies, see sidebar, “The Post-AI Consumer.”)

The Post-AI Consumer

With infinite media come infinite web pages, emails, answers, and content. Managing that expanse is far past human cognition, however, and so all media channels will soon, if they haven’t already, employ AI to help consumers. This even applies to print media since AI allows for personal publications to be printed and sent, based on a number of factors. Lowe’s home improvement stores already use AI to create printed mailers that leverage personal in-store purchasing data, website behavior, and weather patterns to produce and send a unique mailer for each person. Today, every interaction a consumer has with the infinite media is first filtered through a layer of AI, which surfaces the most contextual experience to the moment. That new reality is the heuristics of modern consumer behavior. In fact, experts project that by 2025, 95 percent of all interactions between a brand and a consumer will happen via AI.8 Looking specifically at the five most common media experiences—search, websites, social, email, and voice—we can see how AI is reshaping consumer behaviors, laying the groundwork for how we must respond.

Every search engine, whether it’s Yahoo, Bing, or Amazon, is powered by some of the largest and most powerful AI on the planet, which returns to consumers a list of perfect answers in a fraction of a second. This power has already changed consumer behavior in significant ways, again eroding many of our long-standing ideas of consumer behavior and how we respond.

The first major change AI has had on consumers is how they find content: they now understand that search engines are more powerful than brand websites. This is why the average number of consumer page views per session on a website has dropped below two pages. Consumers realize that AI will answer their questions far better than the individuals will themselves by fumbling around on your site. And if they don’t instantly arrive at what they’re seeking, they simply bounce back to their search.

Responding to this new consumer behavior means rethinking how we design experiences. Experiences like websites are often designed for “flow”—the brand expects a consumer to move from page to page because the individual likes the site’s button location or size, its offers, copy, or color. But the data is clear: there is no flow. Post-AI consumers don’t go to a second page, because they know that a better experience awaits them elsewhere. This is why marketers in 2019 increased their use of AI on websites by 275 percent,9 leveraging the AI to create a personal web experience for each person in real time. The AI knows what to create by tracking each person’s personal behavior, as well as total audience behavior, combining the two data sets to know not just what the person is looking for but also what others looking for that same thing have already engaged with. All of this allows the AI to create the most engaging experience in any moment. There is no need for the consumer to dive deeper into the site to find what he or she is looking for; the AI surfaces it for the consumer.

Email is another great example of how AI is helping to surface the best possible experience. AI already manages your email by filtering out spam and malicious emails, or placing promotional emails in a different folder. Next there is your actual inbox, which does this same thing again. Only emails from businesses and individuals you’ve previously engaged with make it into your primary inbox folder. If the tool, email program, or messaging application you are using doesn’t already do this, it is only a matter of time before it does. The simple reason is AI makes these experiences better for the consumer by helping people filter through the noise, whose levels are ever rising.

Even after AI has filtered an inbox, there’s still so much content that people are learning ways to manage the glut on their own. Usually they do this by scanning the subject lines, deleting the nonessentials. That means consumers rely on fewer than one hundred characters of text to determine the email’s value. This is a learned behavior of the new world. Marketers must respond by learning new ways of engaging via instant messaging. Rather than crafting mass emails, we should shift to sending communication based on the person’s exact place on the journey, a personal experience made just for that moment.

A second significant piece of the post-AI world is social media. In 2015 Facebook stated that each time a person logged on, more than one thousand posts awaited him or her—yet the user may see only a few dozen while scrolling. Again it’s AI that determines which ones we see, and some posts have been published minutes, days, months, even years before. So social media feeds are not chronological accounts but rather contextual feeds. Again, consumers are being exposed to the most contextual experience, creating new experiences along their journey. To respond, brands must consider context when crafting social content. A simple meme taking ten seconds to create is just as likely to break through as an infographic you spend three weeks working on. The context is the determining factor of its effectiveness, not the content.

The post-AI consumer isn’t just enabled by the technology but changed by it. Now that consumers are being fed only context-based experiences, their desire for those experiences is rising. The new world has changed buyers so fast that they now consider experiences just as important as the product or service you sell. That’s why marketing must become the owners and sustainers of all experiences.

B2C and B2B Don’t Matter—Risk Does

Assuming a generation gap in consumer behavior isn’t the only broad misconception fooling businesses and marketers. Many also believe that B2C buyers are far more affected by the changed media environment than B2B customers. But the same 2017 Salesforce global survey referenced earlier found the opposite: compared with 75 percent of B2C buyers, a full 83 percent of B2B buyers feel more informed than ever before because of technology.13 In fact, across every category B2B buyers are more affected by the new environment than are their B2C counterparts (see table 2-1).

|

B2B vs. B2C attitudes |

||||

|

B2B |

B2C |

|||

|

Technology has made it easier than ever to take my business elsewherea |

82% |

70% |

||

|

Technology is redefining my behavior as a consumerb |

76% |

61% |

||

|

Technology has significantly changed my expectations of how companies should interact with mec |

77% |

58% |

||

|

I expect the brands I purchase to respond and interact with me in real timed |

80% |

64% |

||

|

a. Salesforce, Customer Experience in the Retail Renaissance, 2018, https://www.salesforce.com/form/conf/consumer-experience-report/?leadcreated=true&redirect=true&chapter=&DriverCampaignId=70130000000sUVq&player=&FormCampaignId=7010M000000j0XaQAI&videoId=&playlistId=&mcloudHandlingInstructions=&landing_page=. b. Salesforce, State of the Connected Customer, 2019, https://www.salesforce.com/company/news-press/stories/2019/06/061219-g/. c. Salesforce, State of Marketing, 2016, https://www.salesforce.com/blog/2016/03/state-of-marketing-2016.html. d. Salesforce, State of Marketing. |

||||

The same sensitivity holds true around servicing products postpurchase. Our data shows that 60 percent of B2B buyers say it is very important to receive in-app support, compared with only 43 percent of B2C consumers. Furthermore, 82 percent of B2B buyers say personalized care affects their loyalty, compared with 69 percent of B2C consumers. B2B buyers also hold higher expectations for the digital future. Sixty-three percent of B2B buyers expect their vendors to provide customer service via augmented reality by 2020.

The New Experience Is Multimodal

In 2019, Google proclaimed it had more than one billion virtual-assistant devices in the global market.14 Each assistant is a new interface to our world, changing the way all consumers communicate and what they desire. Why type a search if you can speak your request? Why click if you can just tell the assistant to buy? The rapid rise of voice recognition, along with drastically improved technical capabilities, is creating newly fluid multimodal conversations. Just as we’ve become familiar with working through multiple channels—to be where the customers are—now we must go further to ensure those moments are also multimodal: not just communicating in new formats, but also learning to craft entirely new experiences as a result.

Today most of our digital experiences are graphical, meaning that a person engages with images to navigate and accomplish tasks. Think of a website, or your computer desktop. Before the graphical interface, digital experiences were command based. DOS-based commands were required to access programs and run them. Bill Gates changed this with graphical user interface (GUI), and the creation of Windows taught us the power of the click. In the infinite media era, the rise in voice recognition and conversational interfaces means that clicking on websites and navigating through graphical interfaces are going away. Why? Just as GUI was faster than DOS, in many cases a conversation is faster still and better suited to accomplishing the task at hand than, say, pointing and clicking.

For example, it takes me seven clicks to make a payment through my bank’s online website. Banks like Ally, with its Assist bot, now allow a consumer to simply tell the bot who to pay and how much. The goal is accomplished with zero clicks, with a fraction of the effort. Conversational interfaces are much faster at accomplishing tasks than GUI in many cases, but not all.

As voice begins to change consumer behavior, we must keep in mind the need for speed. Sometimes it is faster for a consumer to read than to listen. Think of product options as an example. If I asked, “Alexa, what are the latest designs in men’s shoes?” I still want to see them because I’m able to make a better determination between products visually than audibly. As marketers, we need to think of how to account for such situational differences. This is where multimodal really comes into play. We must be prepared to create experiences that match consumers’ desires, meaning they may ask a question using voice recognition but want the answer displayed on a screen. Conversations today combine all mediums.

Beyond voice, consumers are using new imaging formats to communicate. In her 2019 Internet Trends Report, Mary Meeker cites Instagram cofounder Kevin Systrom, who believes that “writing was a hack” invented by humans when visual images became more difficult to use for communication.15 We have always been visual communicators, he wrote; we just stopped for a while until images became easier to create again, as they are today. In the same report, Meeker also shows that in 2017, people created more than one trillion images. And every day we have new formats of imaging “language” to work with, such as emojis, graphic interchange formats (GIFs), and memes.

The point is that consumers are using visuals to communicate more and more, and marketers must adapt, not only by using them ourselves but also by learning how images can open doors for nontraditional communication. For example, if a customer shares an image of your product, the desired reaction from you is likely just a simple “like” (thumbs-up) of the image or emoji. Consumers view such brand actions as a validation that communicates “I hear you” or “Thank you.” And again, it isn’t just millennials who are engaging in such communication; this is behavior that we have all learned simply by operating in the infinite expanse.

As media channels expand and bifurcate (e.g., Reddit, Quora, TikTok, WeChat, Fortnite), and input methods (voice, images, typing) continue to increase, we marketers will need to keep our focus on what consumers desire to ensure we deliver the experience they want.

If the differences between B2B and B2C behavior no longer matter in the infinite environment, what does matter? The perceived risk associated with a purchase. The riskier the purchase, the greater the consideration consumers will give it and the longer the sales cycle will be. So we should look to classify buyer behavior based on the level of consideration involved in the purchase, rather than the vertical of business or any other factor. Generally, this means traditional B2C purchases are mostly low consideration (less risk), while traditional B2B purchases are high consideration (more risk)—but the exceptions call even this broad stroke into question.

For example, consumers booking an African safari will act much more like traditional B2B buyers because of the risk associated with their decision. There is much less risk in booking a $600 weekend at a hotel three hours from home, compared with $10,000 per week on another continent. Thus, the consumer will give the safari purchase much more consideration and exhibit very different buying behavior. Moreover, even buyers for the same safari product will exhibit different consumer behaviors, based on the risk they perceive. Buyers familiar with the safari market perceive lower risk, and their decision-making process is often shorter.

To work synchronously with the infinite era, business leaders and we marketers must lose our preconceived bias about various categories of consumers and embrace the new consumer decision-making journey, which is based on perceived risk. We must also account for the fact that nearly all decisions are now considered decisions, and that consumers undertake that consideration in a very personal context. (For more perspective on new consumers and their needs, see the sidebar “The New Experience Is Multimodal.”)

The New Customer Journey

Every marketer is aware that the modern decision-making process has changed because of longer sales cycles and the demand for more content (to name only two of many factors). We’re all trying to make the new demands fit into a nice, clean customer journey. And it isn’t just marketers. Consulting firms have put serious research and effort into helping brands understand this shift by publishing their versions of “the new buyer’s journey.” Frameworks like the Sirius Decision Demand Waterfall break the process into these steps: inquiry (inbound/outbound), marketing qualification, sales qualification, close, and advocacy. Other models use the terms awareness, consideration, purchase, and advocacy.

But given today’s environment, those models all make a common error: they see the customer journey as starting with brand awareness, embodied in this description from McKinsey & Company: “The consumer considers an initial set of brands, based on brand perceptions and exposure to recent touch points.”16 For consumers today, however, the decision-making process begins long before they have an awareness of any particular brand—and then they progress on a whole different path from the one they moved along during the limited era. In the infinite era, marketers need to understand that the customer’s decision-making process (which for our purposes is the customer journey) actually begins with a trigger: a moment when the individual comes up with an idea to change something.

The Trigger

A trigger could be your boss telling you to find a new tool or a social post from a friend showing you a stunning new pair of eyeglasses. Triggers also might be something emotional, like a fight with your spouse, or physical, like feeling a hunger pang. Regardless of the specifics, the point is that all consumer journeys start with such a trigger.

For marketers, that’s a major change in perspective. Instead of trying to force change as we once did, by trying to get people’s attention and make them want something, context marketing harnesses and guides an existing desire, one that springs from the trigger.

Think of the trigger as an umbrella-like starting point, from which the consumer then can move to any point along the customer journey, depending on how much information the individual already has about the decision to be made. In other words, triggers jump-start a customer journey or they can restart or continue a journey somewhere along a path already taken.

Batching: Consumer Behavior in the Infinite Era

Batching is a very human response to infinite media, and it refers to two kinds of behaviors. The first is when a consumer is searching for answers to a question and then gathers that set of answers into one place. The second behavior refers to the way consumers often batch many questions together in short succession. These two behaviors are a big key to motivating the modern consumer. Here is why.

Within each stage of the customer journey the individual has a goal, and that goal changes, depending on the stage. For example, in the ideation stage, the goal might be to test an idea and see where the path goes. But in the awareness stage, the goal might be to find possible solutions, to be better informed, or to find solution providers—or it could be all three.

The key to motivating customers is to understand how goals are accomplished via batching, and how brands can take advantage of batching behavior in a way that moves a person onto the next question, goal, or stage. For example, if a consumer is in the awareness stage and the goal is to find out “What is the best look in computer bags,” the person will look at four different websites for answers and spend a total of just over a minute.17 So if your brand can be on as many of those sites as possible, it will more likely break through, build the trust, control the narrative, and then be able to guide the consumer to the next stop on the journey.

Batching also refers to the fact that consumers often ask lots of questions in quick succession. Each batch spawns another, then another, going as long as the consumer wishes. So returning to “What is the best look in computer bags,” an article about the latest tech gear may pop up, and the consumer learns that the look this year combines recycled materials with leather. She then scans three more articles and sees that the most popular color is a two-toned black and tan. The consumer now changes her goal to finding the best-quality two-toned bag, which begins another round of batching and finally leads to a purchase. The entire journey might have taken just a few minutes or could have been stopped and restarted over an entire year or more.

By understanding the modern consumer behavior of batching, we marketers can begin to design our content, programs, and experiences to be easily “batchable,” which allows us to efficiently and repeatedly meet consumers in the context of their moment and motivate them in a new way.

Batching also suggests we should rethink the role of our public relations departments and any attempts to use mass media to create narrative control over our brands. Also referred to as share of voice, narrative control looks at all forms of media occurring at any one point in time and then measures the prominence of a brand’s name. But in the era of infinite media, the only narrative control that motivates the customer journey—and drives demand—emerges from within the batches the consumer gathers by taking an extremely intricate and personal path to find answers. Consumers do this not only because they can but also because they trust their own research and experiences over the messaging of a brand. That’s a critical aspect of today’s environment that none of us can afford to miss. We’ll explore batching in more detail in part three of this book.

For example, if someone rear-ends your car and takes off your back fender, you’ll likely begin looking for an attorney or at the least a body shop. You weren’t thinking about auto repair before the wreck. After the wreck it is front and center. That’s a trigger that jump-starts a customer journey, taking you all the way to purchasing at least one service. But what if the damage to your car was very minor, a tiny dent and no harm really done? You’re not consumed with finding a repair service or lawyer, but you do a few Google searches, ask friends for recommendations, and contact one or two body shops, figuring you’ll eventually get the ding fixed—but essentially you’ve put the process on hold. A few days later, however, one of the body shops sends you an email with an estimate for the repair. That’s a trigger that plunges you back to reengaging with the journey but starting at a different point (further into it) from where you began.

So triggers can occur anywhere along the journey and are different for each person. It’s also important to note that some triggers are much more powerful than others, and that generally triggers fall into one of two categories: natural triggers, which are those that happen to people (like a car wreck) or that they otherwise come upon naturally during the course of their day; and targeted triggers, which brands push out directly, such as an email from sales or a chatbot deployed upon a consumer’s web visit, or by engaging directly via social media. One of the major roles of modern marketers will be to identify natural triggers along their customers’ journeys and work to ensure their brand is part of the journey that the trigger tips off.

Next we’ll look at what happens after a consumer experiences a trigger (of either kind), meaning the individual embarks on the six stages of the new customer journey. As I’ve formulated it, the stages are ideation, awareness, consideration, purchase, customer, and then advocacy. First, however, note that there’s another key aspect of today’s consumer behavior that most discussions and models of the customer-journey process miss: I call it batching. Read about it in the sidebar, “Batching: Consumer Behavior in the Infinite Era.”

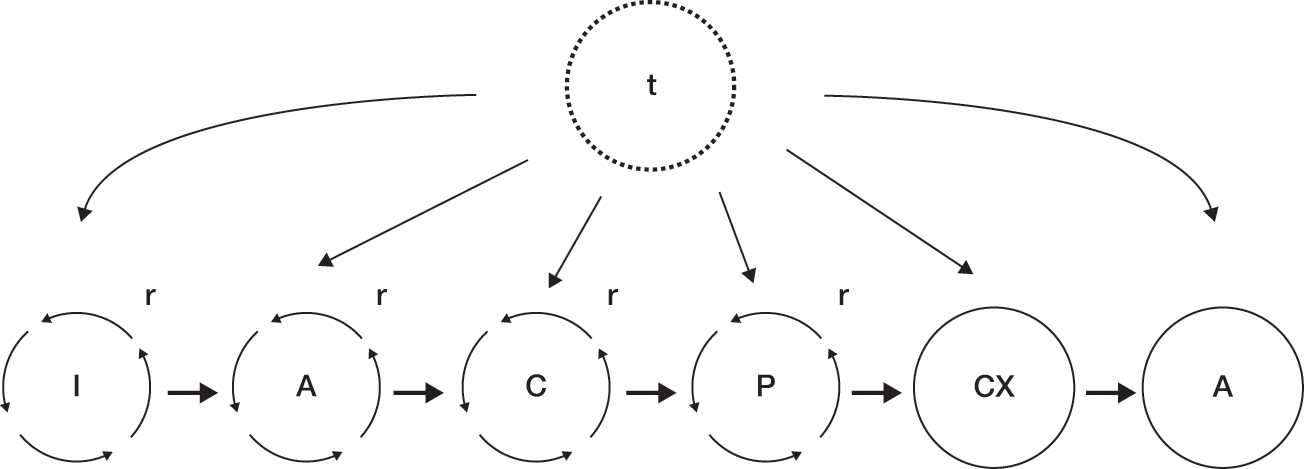

After the Trigger: Six Points along the New Consumer Journey

Once a trigger has kick-started (or restarted) a buyer’s decision-making process, the individual journeys through the six stages, as shown in figure 2-1. Note that “t” stands for the triggers that can come into play at any stage; the letters below the “t” represent the six stages of the customer journey, beginning with ideation and ending with advocacy. (Note that although advocacy is also listed as a final stage in the other marketing models I mentioned in this chapter, the way marketers must carry out advocacy in the infinite media era is quite different, as you will see later in this book.) Finally, note that in the figure the letter “r” signifies the risk involved in the decision, and the arrows surrounding each stage denote batches. (Recall how the number of batches increases according to how risky the consumer perceives the purchase decision.)

The new customer journey

Now let’s look briefly at just the first four stages of the journey: ideation, awareness, consideration, and purchase. Later, in part three, we’ll explore each of these stages in detail, along with the fifth and sixth stages (customer and advocacy).

The Ideation Stage

Think about it: because consumers have access to so much information, their search for a solution does not start by assembling a group of vendors, as McKinsey and others imply. Rather, today’s context-based journey starts with a trigger and then moves to ideation: the consumer has a goal in mind and begins to solve it. The trigger might be a new driving regulation or a demand from your spouse to tidy up. That kicks off clusters of questions and answers that help consumers first clarify their thinking—“How to buy curtains” or “Ways to comply.” This goal is accomplished via the batches that I describe in the sidebar “Batching: Consumer Behavior in the Infinite Era.” All of which brings up an important point: even though businesses usually treat all website visitors as people already interested in their product, the opposite is true. A full 96 percent of the people who visit a website are not ready to buy the product; they’re simply conducting research.18

Where old marketing models stood on the belief that advertising could both spark the idea and drive product demand, today’s marketing task is very different: we must do everything possible to uncover the voluminous questions that consumers pose every day, and be in those moments helping them to achieve their goal. Brands that can’t do that won’t survive. The many, many questions become the batches that naturally construct the modern buyer’s journey (with the number of batches determined by the level of risk).

In addition to queries made through various search engines, many people use apps such as Pinterest, Evernote, and Houzz, which are all what I think of as “ideation apps” that help them form and manage their visions and plans. People using those apps along their journey may be in the early stages, but those people have a higher propensity to buy. A recent study showed that 93 percent of Pinners (people who use Pinterest) use the app because they either plan to purchase or are in the process of making a purchase.19

As your customers distill their ideas, they discover on their own what they need, and they assemble their own buying criteria. That’s when they encounter vendors, as well as the customers of those vendors, through their brand content, and copious reviews. In ideation, customers fully experience several different brands, and the brands that are best able to help their consumers achieve their goal are given the ability to guide them toward the next stop on the journey, and motivation begins.

That’s why recognizing and accounting for the ideation phase is so critical to context marketing. Even McKinsey recognizes its importance, although unaccountably it doesn’t articulate this stage in its own model. But McKinsey research concludes that brands encountered in the initial stages of a buyer’s journey have up to a three times greater chance of generating a purchase than brands that aren’t part of those stages.20 The earlier you are able to establish trust, the greater the effect downstream.

What does all of this mean? That brands should be spending a significant amount of their time and energy preparing and positioning themselves to support ideation by the consumer.

They need to be everywhere buyers are looking, and they need to provide the kinds of answers that meet or exceed consumer expectations, with the tactical focus of guiding them forward.

For example, let’s say that a thirtysomething man, Bill, decides to update his wardrobe. That’s his trigger. Most likely, Bill will hop online to seek out the best ways to refresh his look, and what he finds will set the criteria for his journey. Bill searches for “best fall fashions” and first finds an article on Elle.com talking about the hot new fashions for women. Bill hops back to Google and appends his search with “for men” and tries again. Then he scans the results page and clicks on a few articles he’d like to read. He looks at the first two and notices most of the suggestions require him to buy a full wardrobe. Then he reads the third, an article suggesting that new shoes are an easy way to get the “fall look,” and his number-one criterion now becomes a new pair of shoes. His idea solidified, Bill now enters the awareness stage as he begins his journey to find a pair of shoes.

Note, however, that just as easily as Bill was drawn to buying new shoes, his journey could have led him to achieve a new look in a different way—by buying a linen shirt, getting an expensive haircut, or buying houndstooth pants. We will return to this topic of ideation in part three, but for now understand that it is absolutely critical to be as early as you can in your customers’ journey. The earlier you can help them achieve a goal, the earlier you can build trust and drive greater demand for your brand.

The Awareness Stage

Once Bill is clear on the idea of shoes as the way to refresh his wardrobe, he has a new goal: to find out what shoes will work best. To accomplish this goal, he has to become aware of the options, thereby entering the awareness stage to further refine his search to shoe styles and materials.

Again, and likely even in the same browser session, Bill does another search, “best shoes for fall, men.” But once again he’s faced with lots of content options, and he decides to scroll through the image results, hopping back and forth between sites, each time noticing a shoe, clicking the image, and visiting the site. Finally he realizes the shoe style he wants is called “monk strap.” He goes back to Google and searches “best monk strap shoe, men,” and he goes directly to the image search. At last he sees the perfect pair, but his journey is far from over.

The Consideration Stage

Bill is now sure he wants this monk strap look, and he has a specific shoe in mind. But because Bill has narrow feet, he has a few more questions before he can buy the shoes online. For example, do they run wide or narrow and how well made are they. Bill quickly batches these actions together as he checks the shoes’ quality by reading three reviews. He is comfortable with this brand from the reviews so he proceeds to check the fit, using the True Fit application he finds on the brand’s own site.

Additionally, Bill might search for different colors and options in this stage. If these questions are easily asked on the site, he will stay there—if not, he will return to Google to gather another batch of answers. Finally, Bill has narrowed down his desire and is ready to take the next step: fulfilling that desire.

The Purchase Stage

During the purchase stage, consumers focus on final details of the transaction: price, delivery method, and so forth. To be sure he’s getting the best price, Bill does a search using the specific details of the shoes he seeks: “blue suede monk strap shoes 10M Johnston Murphy under $200.” Again Bill is given a list of highly contextual results in a fraction of a second. He sees that all the prices are the same. But Bill is a serious discount shopper and does one more thing. He searches for a “coupon” for the shoe company and finds a 10 percent off deal posted on a couponing site. Finally, Bill navigates to his shopping cart and buys the $200 shoes. When they arrive, he’s thrilled to feel that he truly has completed a new look for himself.

Bill’s entire journey consisted of multiple batches of answers and lasted a short period of time—likely minutes, not hours. His level of consideration (midlevel, not high or low) for a consumer product is the result of his ability to ask the questions, and his motivation to purchase the shoes was a direct result of the experience he found on his journey. Now Bill’s customer journey moves into the brand’s court; it’s up to that shoe brand to create an amazing customer experience, with the hope of creating an advocate out of Bill. But we’ll get to that in part three. The point here is to show how many different brand experiences Bill encountered in quick succession. Batching within each stage of the consumer journey is a heuristic behavior (taught to us by our media environment—that’s right, McLuhan again) that increasingly all buyers exhibit. Why? Because this is how consumers choose to use the considerable power they wield in the infinite era.

The idea of the customer journey is not new; what’s new is the way we must approach it, manage it, and use it. Brands must embrace consumers’ freedom and realize that they feel most motivated when they’re guided along their own journey. The full expression of that journey happens over time. It’s the by-product of brand experiences that somehow break through and deeply touch the individual, because that person has been met in his or her personal context of the moment and has been moved to take the next step in the context-based revolution.

Next, part two will examine the five elements of context, so we’ll know what each moment must entail.