6.

Personal

Going Beyond How Personal the Experience Is to How Personally You Can Deliver It

Every moment in the infinite media environment is personal, and no two moments are ever the same. Your mobile device is set to your specific preferences and displays an array of apps chosen by you. Every media channel you visit filters tens of thousands of experiences down to a handful, just for you. Your entire relationship with media is recorded in your every action—from which the environment infers your desires—allowing it to serve you increasingly personal experiences in increasingly relevant and meaningful context.

In other words, delivering your brand’s experience in a personal way, the third element of our context framework, has become the new baseline for motivating modern consumers. Personal goes far beyond superficial personalization of content (which has been around for decades—think of mass mailers addressed to you personally or mass emails that start with a personal greeting that includes your name). Rather, it builds on the other elements of the framework to meet individuals in your audience where they are—in the moment—reaching a deeper personal connection.

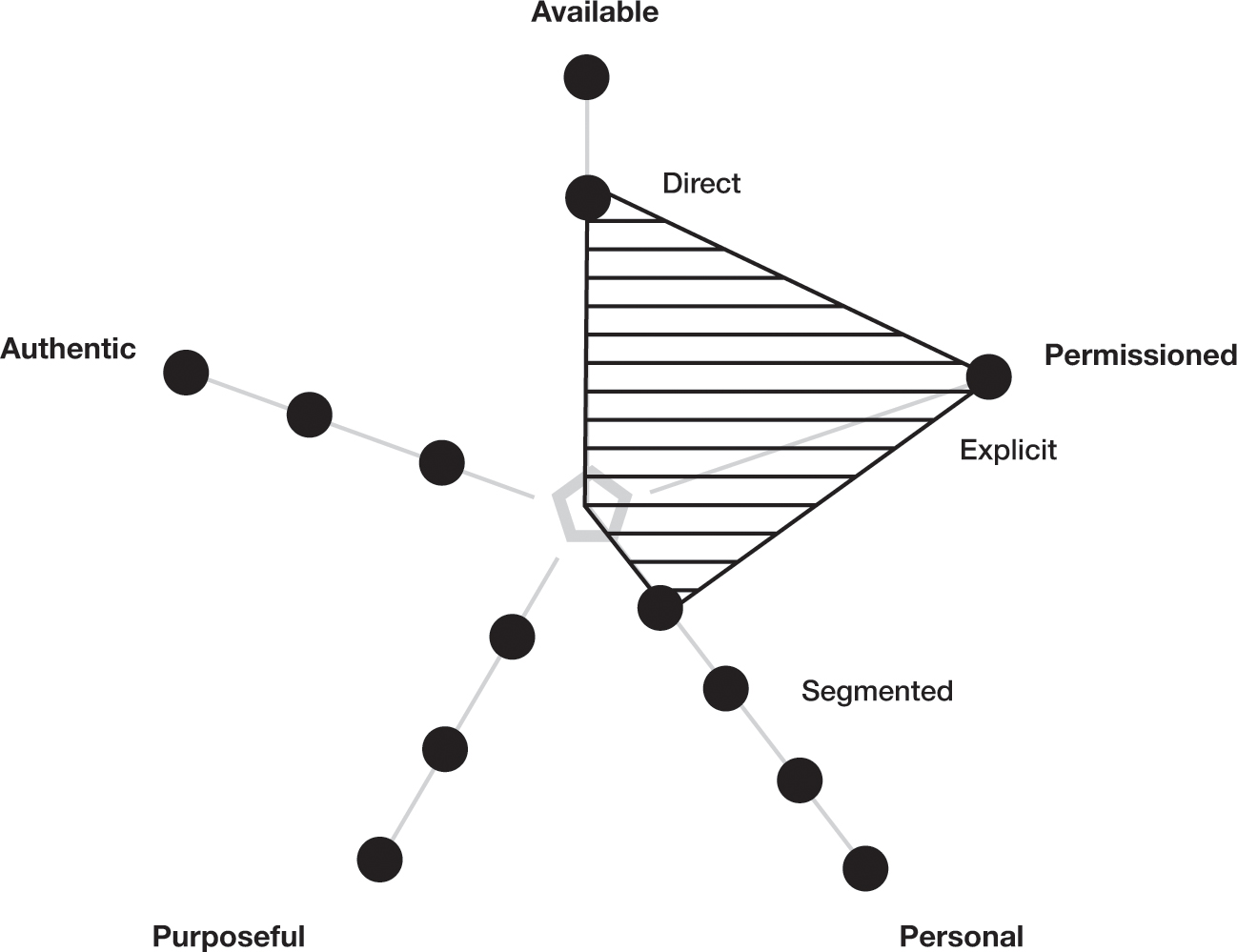

As with the other elements, there’s a continuum of how personal you can make your brand experience (see figure 6-1). Mass campaigns are the least personal/contextual because the brand experience is public and reaches everyone in the same way. A bit more personal is segmentation, in which you tailor your brand experience to a smaller group of some kind, making it more useful to those specific people.

The context framework (personal)

One-to-one efforts are more personal still, because your brand has crafted an experience for a single person, customized to match the person’s needs at a specific moment. Such experiences are very contextual, but because they’re still conducted between a brand and a person, they don’t reach the apex of what the personal element can deliver: human-to-human interaction. This most contextual level on the personal continuum involves direct contact, where the experience is not only unique but also delivered by one human to another—usually brand employees, brand advocates, or members of social or other communities, all working on a brand’s behalf. Let’s look at each of those levels more closely.

Mass Campaigns

At the lowest point on the continuum, mass campaigns are familiar to us all: making a brand experience available in a way that will reach as many people as possible with a single act. That might mean anything from a billboard ad to a TV spot on a cable channel to an email blast sent to an enormous list of names. In the golden age of advertising, during the limited media era, mass campaigns were the way—the only way—advertisers reached customers, through the media channels of that time. While outdated now, those methods were highly effective at the time. Many of the most acclaimed marketing campaigns of all time were created via mass media, such as the Think Small campaign, which launched the VW Beetle into the hearts of Americans and made it the best-selling car ever (at that time, which was 1972).1 The entire campaign was mass media.

Today mass campaigns rarely motivate consumers, for all the reasons we’ve discussed about how the infinite media era works: consumers can ask any question and receive a trusted answer in an instant, thereby killing the power of forced messages to drive consumer behavior. But even though consumers have found a better way to operate today, mass campaigns to distribute brand experiences can easily become more contextual. They just need to use a basic segmentation, the next level up the continuum of the personal element. The delivery works much the same as with mass campaigns, except the experience goes to smaller groups and uses some basic personalization in the message.

For example, you could hire an influencer on social media to message his or her entire audience a uniform communication about your brand. That would make your mass campaign at least permissioned (explicitly) and available (directly), between influencer and audience. In the context framework, that campaign would begin to look like what we see in figure 6-2.

Plotting the elements of available, permissioned, and personal

Segmentation

Moving up the continuum of the personal element from mass campaigns that marketers deliver in a segmented way, we arrive at the fullest expression of segmentation. Like mass campaigns, segmentation is also well known to marketers. We segment brand experiences by tailoring them to a smaller geography, interest, or activity. This makes the experience more useful to that group, increasing the likelihood of engagement. For example, Spartan Race, an organization that creates obstacle course–based running races, segments its email list by geography. The messaging in the emails changes based on the subscriber’s location, with an aim to increase the number of registrants at every race. I live in the southern United States, and as someone who has raced in a Spartan Race in the past, I receive information about races in cities near me. Segmenting is a great way to improve how relevant your context becomes, especially if you even slightly tailor your message to the more targeted group. It’s not wildly personal, but definitely more contextual, as shown in figure 6-3.

Increased context by expanding the available and personal elements

One-to-one

Reaching a still greater level of context are one-to-one brand experiences. These are created by the brand and delivered to a single person at a single moment. While well understood in theory, such experiences are much less common in practice because of the technical requirements to carry them off. One-to-one is a true tool of the infinite media era. Here’s how it works: marketers combine an individual’s personal data with technology that allows them to precisely customize the brand experience, content, channel, timing, and delivery. Recall the example from part one of the furniture brand Room & Board. The company designed its website to fluidly create a unique experience for each visitor, driven by his or her personal data. Room & Board also leveraged artificial intelligence to further contextualize its brand experience. The AI captures and analyzes—via implicit permission—the behavior of visitors to the site, instantly using that data to create a hyperpersonal experience for each person. Note that this level of one-to-one can only happen with advanced technology, specifically AI.

Similarly, ServiceMax, a software solution for the field service reps from GE Digital, uses predictive AI to identify the best content for each site visitor, in the moment, based on real-time data automatically gathered to optimize that person’s experience. After implementing predictive AI on its site, ServiceMax reduced bounce rates by 70 percent, increased conversions by three times, and upped total demo requests by six times.

No doubt, one-to-one is highly contextual. But because it is the faceless, amorphous brand delivering the content, it is not as contextual as the ultimate on the personal continuum: human-to-human.

Human-to-human

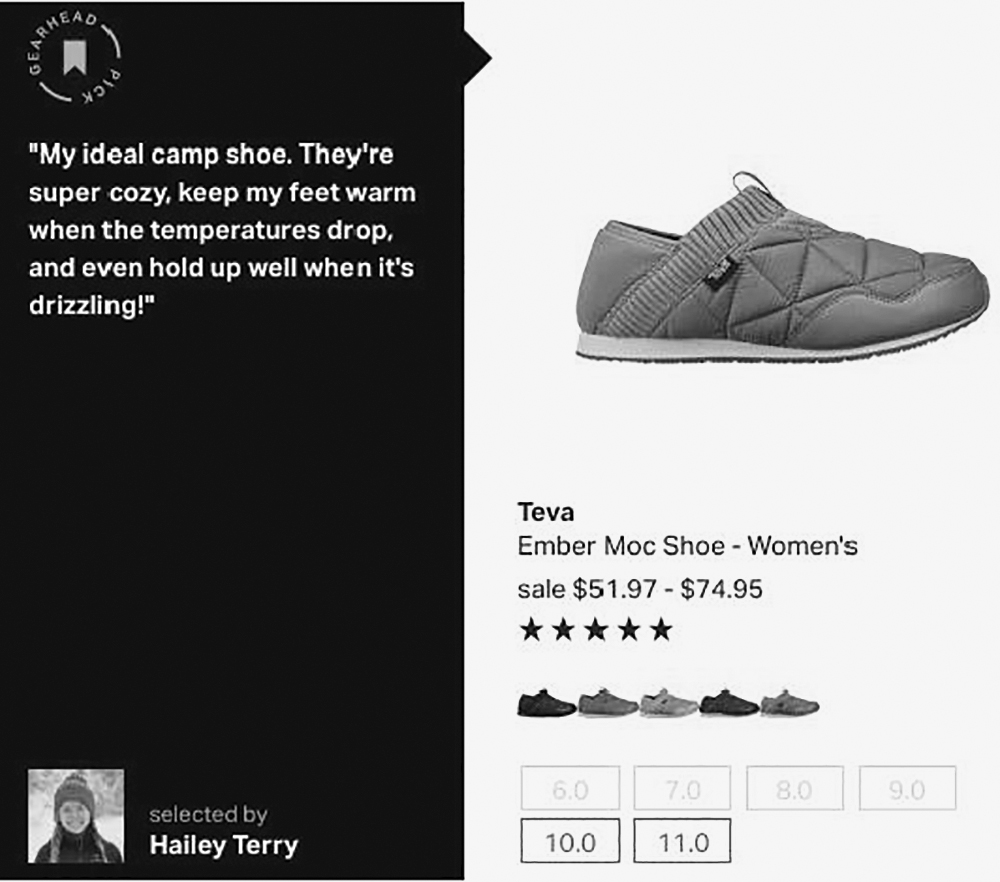

Human-to-human experiences break through not because they are personalized but because they are delivered personally. Backcountry, an online outdoor retailer, offers a great example of this most contextual personal experience. Backcountry’s website creates personal experiences through content that is dynamic and predictive. For example, if you are searching for a camp shoe, the site will include in its results some other products that people like you have “ultimately purchased” or “also viewed.” A personal note written about the product by the user community will also appear (see figure 6-4).

So the website effectively predicts the products you want based on the actions of other purchasers just like you. Moreover, there are numerous reviews of each product from the Backcountry community, and live chat is there to help customers in real time. But the personal experience doesn’t end there. Backcountry is capable of reaching every customer, human-to-human, with its Gearhead program, which I experienced myself.

A few days after I bought some snowboarding gear on the Backcountry site for an upcoming trip, I received a phone call from Wesley, a “Gearhead.” He was calling to ask if I had any questions about my new gear or if I wanted to chat about snowboarding. I told him about my upcoming trip, and I genuinely enjoyed our brief conversation. Later that day I received a personal email from Wesley as a follow-up. The sole purpose of all the communication was summed up in this one line of his email: “Whether you have issues with returns, want to place an order, or just want to call up to chat about some gear for an upcoming trip, I am available.”

To be clear, Wesley was not trying to sell me more stuff (not directly); rather, he was looking to build a personal, lasting relationship. After this amazingly effective encounter, I looked more deeply into the Gearhead program. Backcountry employs 150 Gearheads, whose responsibilities range from managing larger accounts to overseeing the online chat and, of course, direct customer engagement. What makes this program different from others I’ve researched? Gearheads are assigned to an activity in which they have genuine expertise, such as mountain biking, snowboarding, and climbing. This means that when Gearheads reach out to customers, as Wesley did with me, the conversation is engaging and substantive. Someone with only textbook knowledge of a sport like snowboarding is not going to be able to converse at the same level.

Chris Purkey, vice president of sales and customer experience at Backcountry, told the magazine Retail TouchPoints that the Gearhead program’s direct and personal approach to building customer relationships has increased the lifetime customer value of those customers 40 percent over those not engaged with the program, and it has increased ordering behavior by 105 percent. Purkey believes the program will drive $100 million of business for Backcountry within two years.2

At first glance, it might seem that involving the human hand (or voice) makes this approach unscalable, but that is not the case. Purkey believes that without automation, a Gearhead staff member is limited to managing only two hundred customers at a time. It simply is too time-consuming to know who to reach out to, what to talk about, and when. Managing even such a small set of customers would be a full-time role without technology. But with the correct technology, this personal outreach could easily scale to ten thousand customers, each in a human-to-human way because the technology can guide the Gearhead to the correct conversation to be had, at the correct moment. (More on how to apply automation in part three.)

Backcountry is one of those rare high performers that have changed their idea of marketing by aspiring to the most contextual goal on the personal continuum: human-to-human brand experiences. The result? Its marketing department has created a sales force whose explicit goal isn’t to sell more product but rather to build relationships and aid consumers. That in turn adds significantly to the bottom line.

Some brands don’t need to change their idea of marketing; they start out with contextual practices and never look back. That’s what Mark Organ, marketing visionary and cofounder of Eloqua and current CEO of Influitive, told me in a recent conversation for this book. Organ says he’s seen many newly launched brands forgo making traditional marketing hires in their early stages. Instead, they hire “community managers,” who specialize in developing individual relationships with targeted audiences and customers to jump-start results. This very personal, direct engagement gives those early-stage brands two very powerful things: direct access to key influencers in the community, and a platform they can then leverage to drive up the context of their future efforts. Later, once they have their community going, they bring on the additional experience of SEO, email marketing, and so on, leveraging their community—not force—to extend the reach of their efforts.

The role of the community manager changes, depending on the specific organization. But generally it’s someone who is actively managing and growing the community. The key is to think of community managers as coaches and the members as teammates. The coach is always recruiting, organizing, and working directly with each player to accomplish a goal. The focus isn’t on the coach but on the players. This same analogy should hold with the experiences you’re asking your community to share. The brand (coach) should be in the background, with the focus on common connection shared by the community.

This topic of a brand’s community goes deeper than your standard subscribers, fans, and followers. Community not only defines an effective part of human-to-human brand experience; it also represents one of the starkest differences between traditional and context marketing. Let’s look at it more closely.

Making Things Personal Through Your Brand Community

Ultimately, all brands need to move toward a more distributed community model. Call those communities social influencer programs, employee advocacy groups, and brand ambassadors. They all mean essentially the same thing: people, whether employees, social influencers, or brand advocates, who take actions to promote your brand by using their own personal social channels.

Why are such communities so critical to context marketing? They open exponentially more doors to human-to-human contact through each community member’s own list of friends, followers, and the like, and each member’s personal connection to their audience makes it more likely that the experience will break through, far more so than if the brand tried to break in from outside the community. Additionally, when multiple people begin to share an experience, the combination engagement signals the AI, increasing the total reach. The combined audience of such advocates and influencers is likely far bigger than your brand’s, making your brand experience infinitely more contextual. Even more important: the deeply developed relationships that these community members have with their followers allows your brand to immediately benefit from the trust those people have built with their audiences over time. That’s the power of brand advocates.

Brand Advocates and Their Superpowers

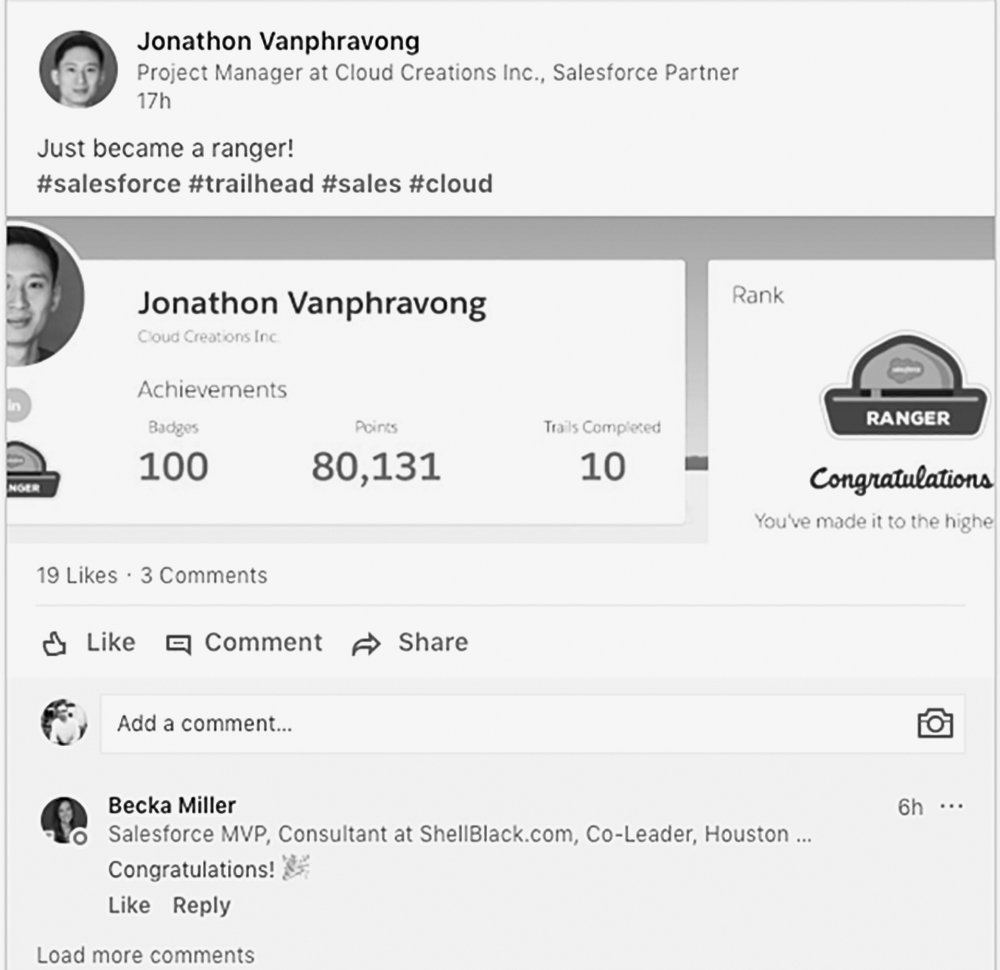

Brand advocates are a very powerful tool that marketers now have at their disposal. Remember, in the infinite era, everyone can create media, so rather than compete with that content, brands need to find ways to leverage it. At Salesforce, we have created a team of Salesforce customer MVPs who love the brand so much, they have become brand advocates. They help Salesforce create greater community and strengthen the bond between our brand and our customers. MVPs support the Salesforce Trailhead program, an education platform where individuals (not just customers but anyone who wants the training) can join, learn, and improve their careers by posting better results using our technology. Participants earn “badges” for completing courses on a wide range of topics, from how to begin using the Salesforce technology to best practices in sales, service, and marketing.

When Jonathon gained a new badge as part of Salesforce’s Trailhead community, he shared the news on LinkedIn (see figure 6-5). Salesforce liked his post, and so did Becka, a Salesforce MVP. Because her comment on his post is human-to-human, it carries more weight and also reflects well on the Salesforce brand. That’s how brand advocates like the MVPs at Salesforce take actions on a brand’s behalf to strengthen relationships with customers and extend the brand, human-to-human, in highly contextual ways.

Source: Author’s LinkedIn feed.

Here’s another example. SocialChorus, a social marketing technology company, found that a firm’s employees have on average ten times more social connections than does the brand itself. Tesla, for example, has a little more than two million followers, while Elon Musk, its CEO, has more than twenty-two million followers. Many companies have a number of high-level staff with a strong following on a variety of social media platforms, but even the smaller followings of regular employees can be very powerful brand extenders, allowing your human-to-human efforts to scale. The math works out that leveraging 135 employees’ social handles to share brand experiences creates the same impact as a single brand audience 1,000,000 people strong.3 Considering the average B2B brand has a social following of only 50,000, using the same math, it would take only six people to reach an audience of the same size.

Many companies will enlist associates from several departments to promote relevant brand experiences (for example, your IT people would promote technology-related experiences and conferences). But at a minimum, all marketing and sales people should be using some of their time to share and engage with posts on behalf of your brand, as well as comment on and share content posted by related brands, industry leaders, and members of your brand audience. That is the kind of activity that increases your brand’s human-to-human interactions—and the overall context of your brand experiences.

Sales teams can take enormous leaps forward by becoming brand advocates and using human-to-human brand experiences to create the connections that move leads along the customer journey. This is commonly referred to as social selling. In fact, AT&T used human-to-human experiences as its primary method for breaking into new accounts, reaching key prospects through a combination of targeted social media conversations and content sharing. The AT&T sales team began by researching the social media presence of key prospects as well as the industry professionals those prospects would be interested in following, specifically on Twitter and LinkedIn. The team used the “follow first” method described in an earlier chapter and joined the same groups as these people, multiplying their potential ways to connect by commenting on similar threads and, perhaps, joining the same conversations about the issues that matter to their prospects.

Again, keeping the brand in the background is absolutely crucial to the success of human-to-human contextual marketing. So when AT&T salespeople interacted with prospects and industry leaders, they were not at all “salesy” in their comments or questions. Communicating from their own (permissioned) social handles, they engaged in social media messaging, mentioned key prospects in the threads of relevant posts, shared content directly or with entire groups, and congratulated prospects on business awards—staying focused on the conversations that matter to their prospects and the industry, not necessarily to AT&T. The cumulative effect of this activity was the creation of multiple human-to-human relationships that are very difficult to create through phone calls and email. Why? Because cold calls have no context. Phone calls are valuable, as Wesley proved earlier, but only work when there is sufficient context. Cold calls are devoid of context, but a follow-up from a purchase isn’t. Moreover, people are not interested in giving their time and attention to “a brand,” but they might to a person—as I did to the Gearhead who contacted me. That distinction is important: the AT&T engagements that occurred were not with AT&T the brand but rather with a person who happens to work there.

Referring to this contextual effort, an AT&T employee reports: “By asking specific questions related to the content and by mentioning specific customers and people of interest on Twitter, we received engagement from customers, who began to ask questions or agree or challenge points we made in the blogs … They told us our approach was ‘refreshing’ because we were building relationships without bombarding them with sales calls, emails, and meetings” (as the competition was doing). This tactic of identifying a community first, and actively becoming a part of it through human-to-human experiences, is the apex of the personal element repertoire—and it landed AT&T a total of more than $40 million in new business, directly from this effort.4

Once your brand experience breaks through, because you’ve made it personal as well as available and permissioned, the final two elements of context—authentic and purposeful—will determine how your brand is received and whether your audience will interact with it. In other words, the final two elements of the context framework are the ones that determine its success in the end. Much more than mere final touches, they are the heart and soul of the context revolution. The next chapter explores the element of authentic.