Hazel Rose Markus and Alana Conner

Hazel Rose Markus is the Davis-Brack Professor in the Behavioral Sciences at Stanford University and coauthor (with Paula M. L. Moya), Doing Race: 21 Essays for the 21st Century. Alana Conner is a science writer, social psychologist, and curator, The Tech Museum, San Jose, California.

Pundits invoke culture to explain all manner of tragedies and triumphs: why a disturbed young man opens fire on a politician; why African-American children struggle in school; why the United States can’t establish democracy in Iraq; why Asian factories build better cars. A quick click through a single morning’s media yields the following catch: gun culture, Twitter culture, ethical culture, Arizona culture, always-on culture, winner-take-all culture, culture of violence, culture of fear, culture of sustainability, culture of corporate greed.

Yet no one explains what, exactly, culture is, how it works, or how to change it for the better.

A cognitive tool that fills this gap is the culture cycle, a tool that not only describes how culture works but also prescribes how to make lasting change. The culture cycle is the iterative recursive process whereby people create cultures to which they later adapt, and cultures shape people so that they act in ways that perpetuate the cultures.

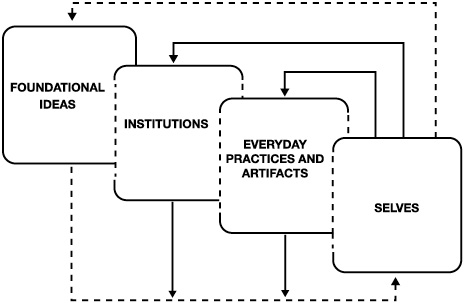

In other words, cultures and people (and some other primates) make each other up. This process involves four nested levels: individual selves (one’s thoughts, feelings, and actions); the everyday practices and artifacts that reflect and shape those selves; the institutions (education, law, media) that afford or discourage those everyday practices and artifacts; and pervasive ideas about what is good, right, and human that both influence and are influenced by all four levels. (See figure below.)

The culture cycle rolls for all types of social distinctions, from the macro (nation, race, ethnicity, region, religion, gender, social class, generation, etc.) to the micro (occupation, organization, neighborhood, hobby, genre preference, family, etc.).

One consequence of the culture cycle is that no action is caused by either individual psychological features or external influences. Both are always at work. Just as there is no such thing as a culture without agents, there are no agents without culture. Humans are culturally shaped shapers. And so, for example, in the case of a school shooting, it is overly simplistic to ask whether the perpetrator acted because of mental illness, or because of a hostile and bullying school climate, or because he had easy access to a particularly deadly cultural artifact (i.e., a gun), or because institutions encourage that climate and allow access to that artifact, or because pervasive ideas and images glorify resistance and violence. The better question and the one that the culture cycle requires is, How do these four levels of forces interact? Indeed, researchers at the vanguard of public health contend that neither social stressors nor individual vulnerabilities are enough to produce most mental illnesses. Instead, the interplay of biology and culture, of genes and environments, of nature and nurture is responsible for most psychiatric disorders.

Social scientists succumb to another form of this oppositional thinking. For example, in the face of Hurricane Katrina, thousands of poor African-American residents “chose” not to evacuate the Gulf Coast, to quote most news accounts. More charitable social scientists had their explanations ready and struggled to get their variables into the limelight. “Of course they didn’t leave,” said the psychologists, “because poor people have an external locus of control.” Or “low intrinsic motivation.” Or “low self-efficacy.” “Of course they didn’t leave,” said the sociologists and political scientists—because their cumulative lack of access to adequate income, banking, education, transportation, health care, police protection, and basic civil rights made staying put their only option. “Of course they didn’t leave,” said the anthropologists—because their kin networks, religious faith, or historical ties held them there. “Of course they didn’t leave,” said the economists—because they didn’t have the material resources, knowledge, or financial incentives to get out.

The irony in the interdisciplinary bickering is that everyone is mostly right. But they are right in the same way that the blind men touching the elephant in the Indian fable are right: the failure to integrate each field’s contributions makes everyone wrong and, worse, not very useful.

The culture cycle illustrates the relationships of these different levels of analyses to one another. Granted, our four-level-process explanation is not as zippy as the single-variable accounts that currently dominate most public discourse. But it’s far simpler and accurate than the standard “It’s complicated” and “It depends” that more thoughtful experts supply.

Moreover, built into the culture cycle are the instructions for how to reverse-engineer it: A sustainable change at one level usually requires change at all four levels. There are no silver bullets. The ongoing U.S. civil rights movement, for example, requires the opening of individual hearts and minds; the mixing of people as equals in daily life, along with media representations thereof; the reform of laws and policies; and a fundamental revision of our nation’s idea of what a good human being is.

Just because people can change their cultures, however, does not mean that they can do so easily. A major obstacle is that most people don’t even realize they have cultures. Instead, they think of themselves as standard-issue humans—they’re normal; it’s all those other people who are deviating from the natural, obvious, and right way to be.

Yet we are all part of multiple culture cycles. And we should be proud of that fact, for the culture cycle is our smart human trick. Because of it, we don’t have to wait for mutation or natural selection to allow us to range farther over the face of the Earth, to extract nutrition from a new food source, to cope with a change in climate. As modern life becomes more complex and social and environmental problems become more widespread and entrenched, people will need to understand the culture cycle and use it skillfully.