TABLE 9.2. Targets of Intervention for Family Sessions in Crisis Situations

Family work is important because the contingencies in the home environment often play an important role in an adolescent’s dysfunctional behavior. Working with the teen’s family enables the therapist to gain insight into the transactional nature of the problem behaviors and directly address the interactions among fa mily members; recognizing and highlighting these transactional relationships are crucial. The therapist also encourages parents to employ the same skills their teen is being asked to use, and ultimately to alter the ways in which they respond to their adolescent’s behaviors. Through the use of various interventions, the family members are recognized as partners rather than targets in treatment; hence the family feels more connected to and supported by the therapist, through ample amounts of validation and consistent family sessions.

Family members can participate in various modes of DBT when an adolescent child is the primary client. First, family therapy sessions provide a context for the family members and the adolescent to interact in the presence of the therapist, who can offer coaching to help address current problems and conflicts. This offers a strong opportunity for skill strengthening and generalization.

Second, the skills training mode (conducted either in the multifamily skills group format or individually with a family) allows family members to learn skills simultaneously with the adolescent. This enables them not only to serve as coaches, but to acquire skills themselves that are essential to productive interactions with their child, such as regulating emotions and communicating effectively. Note that although the multifamily skills group format is typically conducted in outpatient settings, some inpatient and residential treatment settings have begun offering skills training groups for families as well. Another means of teaching family members skills is a program that teaches family members DBT skills independently of their adolescent children. In one model of such a program, the group teaches family members DBT skills and then has graduates of the program train other family members in the skills (e.g., the Family Connections program; Hoffman, 2004). In a similar program, Porr (2004) runs the skills group with family members and coteaches with her own graduates. Similar programs exist around the United States.

Sometimes it is not possible to have family members participate in a multifamily skills training group, a parents-only skills training group, or even skills training with their own individual family members (single-family skills training). In these cases, therapists might find it useful at least to orient family members to the treatment, the biosocial theory, and the skills training, through such means as one-time orientation groups, parent workshops, or support groups for family members.

Third, telephone consultation with family members helps them further with skills generalization and provides a forum for helping them through crisis situations. Again, this mode mostly applies to DBT conducted with adolescents in outpatient settings, where ongoing parent–adolescent interactions spark conflict or crisis that needs immediate intervention.

Because the skills training mode is described in depth in Chapter 10, including ample attention to familial issues, we do not describe it here. Instead, we focus in this chapter on family therapy sessions, phone consultation with family members, and handling adolescents’ suicidal crises with family members; we also briefly address how to handle issues of confidentiality. First, however, we emphasize the importance of taking a nonpejorative stance toward both adolescents and their family members in all modes of family treatment.

It is important to assume a nonpejorative, nonblaming stance with family members as well as with adolescent clients themselves (Miller et al., 2002). Parents or caregivers of multiproblem suicidal teens often experience intense feelings of shame and failure (Miller et al., 2002). They have intense fears for the safety of their children and guilt about their role in the adolescents’ difficulties. Parents who experience strong negative emotions are more likely to communicate irritation and dysphoria if they believe they are incompetent (Clarkin et al., 1990). Reducing parental emotional vulnerability may not only increase treatment compliance, but also strengthen parental capacity for learning new behavioral skills. Therefore, it is important to remember that well-meaning family members can invalidate a teen for various reasons, and that DBT assumptions for the client also apply to the family, as we will see in Chapter 10. For example, the family members are doing the best they can, and they want to do better. Moreover, parents and other family members may not in fact constitute the only or even the primary invalidating environment; school, peer, neighborhood/community, and/or cultural contexts may all play central roles in adolescents’ lives and be a major source of invalidation (see Chapter 3). High levels of invalidation in these settings can have an impact on an emotionally vulnerable teen, especially if parents provide relatively low levels of validation and so do not offset them,

In addition, families often bring a history of prior treatment failures or experiences of being blamed by therapists for their adolescents’ problems. Using terms such as “poorness of fit in temperaments” may facilitate a family’s perception of greater acceptance. Labeling behaviors as invalidating, rather than labeling families as invalidating environments, may also reduce pejorative implications. This not only allows for a simultaneous focus on teaching adolescents to validate their families, but also may help to reduce parental perceptions of global incompetence. Observing family interactions allows the therapist to avoid blaming the parents and to develop a more synthesized and empathic view of the family behavioral patterns. Seeing the adolescent interacting within the family system fosters the therapist’s understanding of the teen’s emotional reactions, skills deficits, and capabilities, while concurrently understanding the family members’ perspectives, skills deficits, and capabilities.

Family sessions are typically scheduled on an as-needed basis. In inpatient, day treatment, or residential settings, family sessions may be scheduled at regular intervals or as deemed useful, and may be the only involvement the family members have with the adolescent’s treatment.

In such cases, the family therapy sessions are typically adjunctive to the adolescent’s individual therapy sessions and do not replace them.

In contrast, given the fact that in most outpatient contexts the adolescent is typically receiving two sessions per week already (i.e., individual therapy and skills training), it is difficult for many families to make it to treatment for a third (family) session during the week, given time and financial constraints. One solution is to schedule a 60- to 90-minute individual session, divide it in half, and conduct the family session during the latter half. This allows the adolescent and therapist to review the diary card privately and conduct brief behavioral analyses of any target behaviors before preparing for the family session. This preparation might entail identifying any relevant target behaviors that involve the family (see below), as well as anticipating some distress and then coaching the teen to use DBT skills during the family session.

Family sessions may be indicated for various reasons: orienting parents to DBT, including psychoeducation; working to facilitate communication between the adolescent and one or more family members about an important issue; conducting a behavioral analysis of a target behavior; or handling a crisis. As a general guide, Table 9.1 lists situations in which a family session is indicated.

Another factor to consider in holding family sessions is which family members should be involved. Typically, primary caregivers such as biological parents or stepparents participate in family sessions and skills training. However, other primary caregivers, such as grandparents, might be included. With an adolescent client, even siblings may at times be included in the family sessions, depending on the extent of the siblings’ involvement with the client and on the focus of the family therapy. As Santisteban, Muir, Mena, and Mitrani (2003) point out, younger siblings are at risk for similar behavior problems, and there is important preventive work to be done by improving the functioning of the family. They further point out that highlighting the urgency of altering the environment for the younger children can be a strong motivator for mobilizing disengaged parents. With other clients, older siblings may be included—perhaps in the role of guardians to the clients, perhaps to address sibling discord related to the clients’ target behaviors, or perhaps to help to expand the clients’ support network.

The Stage 1 targets for treatment of individuals can be modified for family treatment. One of the most common precipitants to suicide attempts among adolescents is interpersonal conflict (Miller & Glinski, 2000). In these situations, the primary target is to decrease family interactions that contribute to the adolescent’s life-threatening behaviors. When a DBT therapist conducts a behavioral analysis of an adolescent’s self-injurious behavior, there is often a link in the chain that relates to familial relationships, or to attitudes or beliefs within the family. This seems to be the case more often for adolescents than for adult clients.

TABLE 9.1. Indications for Scheduling a Family Session as Part of Individual Therapy with an Adolescent

|

DBT sessions also target reduction of family or parent behaviors that interfere with the treatment. To target only the adolescent’s therapy-interfering behavior without considering the parents’ therapy-interfering behavior ignores the reality that parents often have a great deal of power over the adolescent’s capacity to participate in treatment. For example, parents sometimes refuse to drive or give bus fare to their adolescent, or contribute to scheduling conflicts, preventing him or her from getting to individual sessions. It is certainly worthwhile to coach adolescents in interpersonal effectiveness skills to get what they need from their parents, but if this is not effective, a more active environmental intervention should be used (i.e., the issue should be directly discussed in the next family session).

The third target is to reduce family interactions that interfere with the family’s quality of life. The focus is on helping the family as a group function in a more effective, respectful, and loving manner. Among the most common quality-of-life targets are family communication problems. Over time, many families become chronically emotionally dysregulated. Such a family may present as continually angry or with the sense that members are continually walking on eggshells. As a result, members tend to avoid direct communication with one another for fear of aversive consequences. A DBT family therapy session must often first address skills training in validation (see below) to set the stage for future behavioral and solution analyses regarding specific family problems. Because family members are often eager to start problem solving, it is important to orient families to the rationale for teaching validation and interpersonal effectiveness skills before problem solving begins. Anecdotally, this has been one of the most important discoveries we have made in conducting DBT family sessions.

The fourth target, which is related to the first three, is to increase the family’s behavioral skills—particularly in terms of validation, direct communication, and finding a “middle path” for parent–adolescent dilemmas. For example, the standard DBT interpersonal effectiveness skills can be taught to the entire family. It might also be helpful for the parents to have training in specific parenting skills, such as how to develop house rules or use effective reinforcement and punishment. It has been our experience that teaching family members how to validate one another is the most crucial interpersonal skill for improving their relationships; thus, in addition to teaching it in the Interpersonal Effectiveness module, we highlight it in the Walking the Middle Path module. Role plays and family homework assignments help families to practice and generalize this invaluable part of the treatment. Note that if family members participate in skills training (in group or individual-family format), they will learn the DBT skills, but family sessions provide a forum for additional skill strengthening through coaching and in vivo practice.

Dialectical dilemmas (see Chapter 5) abound in work with suicidal adolescents and their families, because of the transactional nature of relationships and the resultant development of certain dysfunctional behavioral patterns. Highlighting a dialectical framework not only serves as a treatment strategy, but provides the foundation for a common language that is learned and regularly employed in sessions.

Once a dialectical dilemma or polarizing behavior pattern is identified and labeled, the challenge is often “What do we do now?” Finding a synthesis to these behavioral extremes, known to clients and families as “finding the middle path,” is the task at hand. As described in Chapter 5, each dialectical dilemma has corresponding treatment targets. For example, consider the extreme behavior pattern of excessive leniency versus authoritarian control with regard to the case of Jessica, discussed in earlier chapters. Jessica and her mother experienced conflict over Jessica’s repeated violations of her curfew. Jessica believed that the curfew times were unreasonable, and stated that they prevented her from spending time with her friends. Her mother found herself vacillating: She was sometimes overly restrictive with the curfew (e.g., having Jessica come home immediately after school), but at other times she felt guilty and wished to avoid relationship tension, and thus she allowed Jessica to break curfew with no consequence or even to abandon the curfew altogether. This vacillation gave Jessica the message that the curfew was arbitrary and not to be taken seriously.

To help the family achieve a middle path, the therapist helped the family with the targets of (1) increasing authoritative (not authoritarian) discipline while decreasing excessive leniency, and (2) increasing adolescent self-determination while decreasing authoritarian control. In Jessica’s family session, the therapist first used simple terms to clarify the dialectic (i.e., “being too loose” vs. “being too strict”) and the tension it caused. Next the therapist elicited the perspectives of both Jessica and her mother, and modeled contextualizing and validating both viewpoints and sets of feelings (i.e., “Jessica, it is perfectly understandable that you want to hang out with your friends, and it is also reasonable that your mom wants to know that you are safe”). The goal here was then to get Jessica and her mother to validate each other directly. In this case, the DBT therapist coached both Jessica and her mother in interpersonal effectiveness skills so each could clearly express her feelings and wishes, make their viewpoints understood, and then validate the other’s feelings, The ultimate goals with any polarized behavior pattern are to (1) help the parents and adolescent increase their problem-solving skills so they can find a synthesis between their opposing viewpoints, and (2) help the individual vacillating between extremes to find an effective middle ground that allows for more consistency in behaviors. So, for example, Jessica’s therapist provided psychoeducation regarding parenting skills (e.g., consistent rules and consequences), suggested the use of positive reinforcement when Jessica came home on time, and encouraged flexibility in the curfew if and when Jessica acted more responsibly.

In sum, the original targets of standard DBT can be modified for family sessions, with the first priority always being the adolescent’s life-threatening behaviors. However, the emphasis of the family targets is on the interactions between family members, rather than on individual behavior. It is important to note that while family interactions can contribute to the problem behaviors, family relationships can also be a source of strength and change that can help the adolescent cope with dysregulated affect.

As a general rule, a family behavioral analysis provides a tool for highlighting both adaptive and maladaptive patterns of family interactions and determining potentially effective change strategies. Such an analysis is conducted when a family member is directly involved in an adolescent’s life-threatening, therapy-interfering, or quality-of-life-interfering behavior (Miller et al., 2002). A behavioral analysis with a family involves eliciting the emotions, thoughts, and actions of family members that relate to an adolescent’s targeted behavior. Conducting a behavioral analysis during a family session requires input from every family member present, to help elucidate the links in the chain of the behaviors that lead to or reinforce the adolescent’s problem behavior This is not to say, however, that every family session requires a formal behavioral analysis. Sometimes a brief assessment of the interaction patterns is sufficient, and the remaining time can be spent on in vivo skills coaching.

Prior to the family session, it may be especially helpful for the therapist to prepare and coach the adolescent on being effective during the session, including anticipating what is likely to go wrong and how to handle it. The first time a behavioral analysis takes place with a family, the therapist should orient the family members to the procedure and its purpose. It can be confusing to elicit a detailed story from two or three people at once. Ground rules can be established, such as the following: Others may chime in to add a detail, but such chiming in should not cut someone off or otherwise be done in a rude manner; descriptive remarks are condoned, but derogatory or hostile remarks should be avoided; everyone will get a chance to comment and offer his or her viewpoint; offering an alternative viewpoint should be seen as a clarification and opportunity for understanding rather than a provocation. The therapist should then collaboratively establish, based on the hierarchy above, the target for the family behavioral analysis, and can ask one family member whether he or she wishes to start; often this person will be the adolescent. The process then proceeds similarly to an individual behavioral analysis (see Chapter 8), except that the family members in the room each share their perspectives or experiences of the various links. Note that observation of family interactions in session during the chain analysis can also help the therapist confirm or disconfirm contingent interactions.

For example, to begin a discussion of events antecedent to her self-harm behavior, Jessica told her father how upset she had been about an argument with her boyfriend. Her father, in an attempt to soothe her, had inadvertently said something that she experienced as invalidating (“Don’t worry, you’ll get over it”). Jessica then ruminated about how misunderstood she felt, which intensified her anger. Later in the evening when her father spoke with her, she cursed at him. In his mind, her angry response seemed to come from “out of the blue.” He screamed back at her, and so on, until Jessica cut herself in order to numb her intense feelings of anger and frustration at feeling misunderstood.

The therapist would first identify the transactional nature of family interactions in this chain. Then, among other things, the therapist might work with the father to help him realize the strong impact this type of invalidation had on his daughter. He might work with Jessica to help her modify her assumption that parents “should” always understand her. He might work with both of them to increase their validating comments to one another. He might also have family members use interpersonal effectiveness skills to communicate without resorting to screaming matches, and apply distress tolerance skills to tolerate their frustration without acting impulsively on it. Role plays are an excellent means of achieving mastery over these new approaches.

The consequences of the target behavior are equally important to highlight in a family behavioral analysis. During the course of such an analysis, one therapist discovered that an adolescent client would stomp around, scream, and hit her father—who would then grab her, go up to her room, get her Kleenex, and sit by her, holding her hand and helping her process her troubles. Similarly, another adolescent would cut herself and spill blood all over the bathroom and bedroom, and then her mother would clean it up. In both of these examples, the well-meaning parents were reinforcing strongly maladaptive behaviors.

In such a case, the therapist needs to work out a plan with the parents in which they either reduce attention to the destructive behaviors or respond with slight aversive consequences, while communicating to the adolescent that they will attend positively to adaptive behaviors (i.e., contingency clarification). Contingency management skills need to be highlighted for the family members, so that they can learn how not to reinforce problem behaviors. In general, these skills include positive and negative reinforcement, extinction, shaping, and effective punishment. Note that it is impossible for parents to completely ignore an adolescent’s suicidal threats or self-injurious behavior; nor should they completely ignore them. The dialectical balance that needs to be maintained here is responding appropriately to real danger, while not overresponding to all such behavior so that danger is increased.

In yet another case, a family behavior analysis revealed parental consequences that were problematic because the parents were repeatedly nonattentive or punitive in response to appropriate behavior, contributing to the learning history of their 18-year-old daughter. For example, the daughter had told them that her older sister, who apparently had antisocial tendencies, had physically attacked her; she even showed them the bruises, trying to elicit their help and protection. They had dismissed her, blaming her for “starting trouble” and stating that the older sister “had enough problems.”1 Her efforts to communicate distress to them were eventually extinguished by this and similar episodes of invalidation, and by the time they entered therapy, she had withdrawn from them. The behavioral analysis revealed the daughter’s feelings of hopelessness about her parents as sources of support, as well as mistrust of their motives. Present sources of distress, then, would not only affect her in their own right but also cause secondary emotions of intense hurt and anger, because she could not talk to her parents. Instead, she resorted to regularly piercing her arms and eyebrows with safety pins to regulate emotion, and to getting validation from a drug-addicted but supportive boyfriend. During the solution analysis portion of the session, the therapist worked to increase the parents’ understanding of their daughter’s mistrust, withdrawal, and distress. He also encouraged them to pay more attention to their daughter and take her seriously. He worked with the daughter as well, coaching her to use distress tolerance skills.

Developing a family crisis plan during a family session can help prevent future episodes of self-destructive or maladaptive behavior. For example, the initial part of a crisis plan for Jessica’s family might go as follows: The next time Jessica’s father saw that Jessica was becoming increasingly angry, he could first try to coach her to use distress tolerance skills. If the father himself was still unfamiliar with these skills, he might call the skills trainer for guidance on how to coach his daughter. Or he might strongly urge Jessica to page her own therapist directly for coaching. A crisis plan should also include several other options—including, in this case, taking Jessica to the emergency room if none of the other strategies worked. It is often helpful to have someone in the family write down the crisis plan and have everyone read, sign, and be familiar with it. The crisis plan often brings distressed families an immense sense of relief, because it provides them with a clear course of action during a chaotic and frightening time.

When involving family members in treatment, we have found it helpful to provide them with phone coaching as an additional mode of treatment. In phone coaching with an adolescent’s family member, it is crucial to assign the role of phone coach to someone other than the adolescent’s primary therapist—to avoid the problem of dual roles, the threat to therapeutic trust, and the potential violation of confidentiality. The skills trainer or coleader (if this person is not also the primary therapist) is an excellent choice for this role, since this person knows the family members yet does not hold a “privileged” relationship with the adolescent. In situations in which the primary therapist is also the skills trainer, and there is not a second skills trainer, we suggest caution in using the primary therapist as parental phone coach. In such a case, both the adolescent and parents must be oriented to the situation. In order to preserve trust with the adolescent, ground rules must be set. These ground rules ought to include the following: (1) The adolescent will be informed when parents have called; (2) if an adolescent and a parent call at approximately the same time, or regarding the same situation, the adolescent’s call will take precedence; and (3) no details about the adolescent’s treatment will be disclosed during a phone call with a parent. Whenever possible, however, we strongly advise having a separate therapist available for family member skills coaching. The dual role is rife with possibilities for feelings of betrayal on the adolescent’s part.

We suggest that the purposes of phone consultation with family members should be in vivo skills coaching (including coaching through crisis situations) and, if needed, relationship repair with the skills trainer. Relationship repair, in which the phone contact can be initiated by either a parent or the skills trainer, is important so that family members (much like teens in treatment), do not ruminate until the next session about perceived slights, misunderstandings, or other difficulties in the therapeutic relationship. For example, in one group skills training session, a parent felt put on the spot by the skills trainer when asked to use skills to address a conflict with her son. The skills trainer could see her distress and followed up with a phone call to repair the relationship, which the mother very much appreciated. Note that phone contact for the purpose of reporting good news is not recommended with parents, although it is used with adolescents (since with parents there is not the same need to break the pairing of increased telephone contact with suicidal crisis).

When an adolescent is in a suicidal crisis, the therapist must consider the family, as well as the primary client. In addition to having rights concerning the adolescent as a minor child, parents sometimes provide the major context in which the adolescent’s crisis behaviors occur. At the very least, parents are brought in so that their child’s disorder can be explained to them and so they can work on minimizing any invalidation. Beyond this, parents can be helpful by providing additional sets of eyes and ears to monitor the client during times of crisis. They can also help alter the eliciting and maintaining events surrounding the crisis. If parents are part of the problem related to the crisis situation or are interfering with therapy, family sessions can be helpful in addressing these problems. If parents are generally helpful, they can be brought in to find ways to maximize their helpfulness in a particular crisis situation.

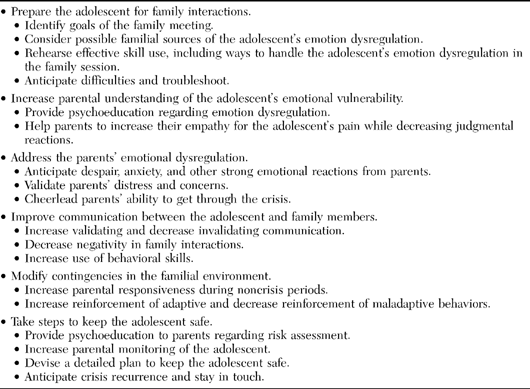

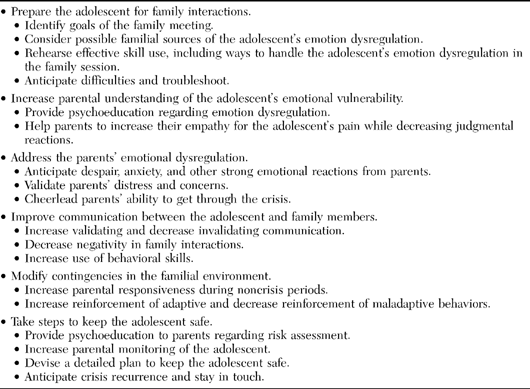

Santisteban et al. (2003) discuss general DBT family therapy strategies that lend themselves well to crisis situations, including identifying family interaction patterns that tend to create barriers to the effective use of skills; preparing the adolescent for family sessions, particularly by inoculating the adolescent against the family interactions that typically trigger emotion dysregulation; educating the parents about the adolescent’s vulnerability to emotion and behavior dysregulation; helping parents to empathize, nonjudgmentally, with the emotional pain driving the adolescent’s extreme behaviors; preparing parents to expect “ups and downs,” so that they can stay more consistently connected; reducing invalidating and increase validating communications; increasing the size of the adolescent’s support network; and modifying family interactions to reinforce adaptive and not reinforce maladaptive behaviors. Based on suggestions of Santisteban et al. (2003), standard DBT strategies, and our clinical experience with including families in treatment, Table 9.2 highlights useful crisis intervention targets with families.

Santisteban et al. (2003) also recommends steps for the therapist to take regarding family work within an inpatient setting when the adolescent has been hospitalized for suicidal behavior. These include holding meetings with the adolescent and family members within the setting; scheduling family sessions prior to discharge, both to address the transition to home and to plan for increased monitoring and safety; and reframing the hospitalization crisis as a step in the treatment process and as a potential springboard toward more adaptive functioning.

In general, the first family members to involve during a crisis are those directly involved in the adolescent’s treatment (i.e., through skills training and as-needed family sessions). These family members already share a focus on the adolescent’s treatment outcome, and are typically already versed in the nature of the teen’s disorder and the DBT approach. They also usually already have some relationship with the primary therapist. However, at times other family members might be brought in. First, if the setting is one in which parents are not routine participants in treatment, they might nevertheless be brought in when a crisis situation develops. Second, if family members are participating in treatment, but a family member who has not been participating is playing a major role in the crisis, this member might be brought in. Third, if the therapist determines that a person not routinely involved with the client’s therapy might be particularly helpful in supporting the adolescent during the crisis, this person might be brought in. In addition to parents and stepparents, who are typically the primary people involved in adolescents’ treatment, we have on occasion held conjoint sessions with grandparents, godparents, boyfriends/girlfriends, and siblings.

TABLE 9.2. Targets of Intervention for Family Sessions in Crisis Situations

Engaging family members in a crisis plan generally involves a combination of soothing, validating, cheerleading, and providing psychoeducation to the parents. In addition, the therapist can apply the standard DBT crisis strategies and treatment-planning considerations, as outlined below.

In most crisis situations, the therapist can expect the parents to be alarmed and emotionally dysregulated themselves. They may be eager to help or take charge, but may have little idea what they might do. The therapist must remember to take time to focus on the parents’ needs and reactions as well as the client’s, since the parents will be the major components of the environment to which the adolescent in crisis is exposed. Not only does the therapist want to avoid having the parents’ responses exacerbate the crisis, but the parents will be needed to cooperate with a crisis plan. At the very least, the therapist may rely on the parents to bring the adolescent in to his or her next appointment and not interfere in the adolescent’s attendance at this time. If time and circumstances permit it, the therapist should assess the parents’ concerns and beliefs regarding the crisis situation. The therapist should validate the parents’ emotional reactions and their perceptions of how difficult the situation is, while reinforcing any statements or actions on the parents’ part that will be helpful in dealing with the crisis.

Providing cheerleading to parents in such situations is important as well. For example, parents may feel overwhelmed and hopeless. Statements indicating a belief in the parents’ ability to get through this crisis, handle it (with the therapist’s help), and do what is needed can greatly encourage emotionally depleted parents.

A major step in securing the parents’ involvement in the crisis plan will involve psychoeducation. Although the focus of the psychoeducation will be particular to the circumstances, it often concerns such topics as biosocial theory, emotion dysregulation, principles of learning, and validation. In addition, the therapist can educate the parents to apply many of the standard DBT crisis strategies (Linehan, 1993a). For example, parents can pay attention to their teen’s affect rather than to the content of a situation. This can be important to teach parents, since parents may see the adolescent’s affect as a prototypical expression of adolescent moodiness or overreactivity and thus may not take the response seriously. Parents can also explore the current (not past) problem; focus on problem solving; focus on affect tolerance; get commitment to a plan of action; assess suicide potential (parents may need the therapist to provide questions for them to ask their teen, such as whether the teen intends to commit suicide and has the means to do so, whether the teen feels able to refrain from self-harm, or whether the teen needs to page the therapist; Table 8.5, which lists signs of imminent risk, may be helpful here); and anticipate a recurrence of the crisis response and therefore closely monitor their child. These strategies are further expanded upon below, and we provide an example of a therapist’s incorporating these steps into a family session.

The first DBT crisis strategy (Linehan, 1993a) concerns paying attention to affect rather than content. For example, if a highly distressed client says, “My parents grounded me again, and I want to die!”, the therapist would pay attention to the suicidal thoughts and the related emotions rather than the issue of grounding. A crisis is not the time to focus on historical factors, but rather to explore the current problem by trying to identify key precipitants of the current crisis. Not only should the adolescent not focus on distal events, but parents should be dissuaded from bringing up historical factors as well. In staying present-focused, the therapist can guide the teen and family through problem solving to address some of the precipitating factors or to tolerate the affect generated by the precipitants. Note that the therapist might have to work with family members to tolerate the intense affect experienced during times of crisis, so as not to exacerbate the situation by reacting with panic or criticism. Once problem solving has occurred, key precipitants have been identified, and strategies to tolerate painful affect have been selected, the therapist must obtain commitment to a plan of action. This plan of action must include a series of steps that will enable all parties to get through the crisis situation by coping with or tolerating it, without engaging in self-harm or doing something to make the situation worse. It should also include troubleshooting—that is, anticipating where the plan is likely to go wrong, and planning what to do then. As discussed further below, with adolescents, family members will often be involved in this plan. Assessing suicide potential (including finding out about intent and access to lethal means, and considering the client’s history) will be important in developing the plan of action. Imminent risk factors (see Table 8.5) should be considered in determining the potential for suicide. Finally, the therapist needs to anticipate a recurrence of the crisis response, and therefore to remain in contact with the client—and, ideally, involve the parents in monitoring the adolescent as well.

In addition to these crisis strategies, standard DBT includes treatment-planning considerations for suicidal behaviors (Linehan, 1993a). These considerations vary, depending on whether the suicidal behavior is respondent or operant in nature (see Table 8.6). If functional assessment indicates that the suicidal behavior is respondent, or primarily elicited by antecedents, the therapist works to change the nature of these eliciting events, teach skills for preventing such events, or teach skills for coping with the events. If assessment indicates that the suicidal behavior appears to be operant, or primarily controlled by consequences, the therapist responds by not reinforcing and by pulling improved behavior from the client before intervening. Note that the therapist often involves family members in these treatment-planning considerations as well.

An example of applying these crisis strategies and treatment-planning considerations involved an 18-year-old client in her third month of an unplanned pregnancy, whose parents had called to ask whether they could come in for a family session because of a crisis situation in which the adolescent was stating that she wanted to die, following a family argument about living arrangements. She was notably tearful and agitated. Paying attention to her affect, the therapist assessed her suicidal ideation, intention, and plans. The client then began a verbal tirade, attacking her father for years of past difficulties in their relationship. Rather than encourage the adolescent to continue this venting, the therapist redirected the conversation to focus on the current suicidal crisis and the events that led up to it. In response to the therapist’s direct questions, the client stated that she wanted to kill herself, and that she would do it with the full bottle of Tylenol and bottle of antidepressant medication she had at home in her bathroom. In addition, she had ingested large amounts of pills twice before with ambivalent intention to die; these episodes had led to hospitalization.

The main precipitant of the current suicidal intent was that her father had told her she could no longer live in the family apartment, and wanted her to move out by the end of the week. Yet she was pregnant, and she perceived that she had no place to go and could not support herself or ultimately care for her baby without help. Thus she felt abandoned and unloved, and wanted to be dead. Her parents explained that their limits had been pushed one too many times, with the last incident leading to their extreme decision to ask her to move out. The night before, when the parents were not home, their daughter and her boyfriend had engaged in a loud argument in which he was cursing and threatening her while pounding on the windows and walls—all in the presence of the two younger siblings. The boyfriend finally stormed out. When the parents returned, the siblings told them of the incident, leading the father to confront his daughter angrily and demand that she move out. They were concerned about her well-being and her future, but were also concerned that she provided a negative role model for their other daughters. They had been allowing her to live with them because they wanted to keep a close watch on her and were afraid of pushing her to become suicidal, as she had in the past. However, this argument with her boyfriend proved a “last straw” for them. They felt that she had now gone beyond making a poor decision for herself and being a negative influence on her siblings, to actually traumatizing them and posing a danger to them. From her perspective, they were abandoning her in her time of greatest need, proving their greater allegiance to her younger siblings—and she felt panicked that she would end up homeless or in a shelter with her baby. She could envision only killing herself as a means to escape her predicament and emotional distress. As the parents and their daughter were recanting the events, the daughter intermittently became tearful and enraged. Thus the therapist worked with her in session to tolerate her current affect by use of mindfulness skills.

Exploring the current problem then allowed the therapist to work on formulating and summarizing the problem situation—a crucial step before problem solving. The therapist decided to focus on the precipitating factors of the suicidality; because the suicidal behavior appeared to be largely respondent in nature, she believed that addressing these factors could mitigate the client’s distress and desperation. The therapist thus began by urging parents and teen to express themselves more effectively, using DEAR MAN and GIVE skills with a particular focus on validating each other’s positions. To begin problem solving, the therapist referred them to the dialectical dilemma of fostering dependence versus forcing autonomy (see Chapter 5), which they had learned about in skills training during the Walking the Middle Path module (see Chapter 10). The therapist asked the family members how they thought this applied to them, and the parents immediately saw that they had flipped from one extreme position to another. For some time, they had been fostering dependence on their daughter’s part by making allowances for her many maladaptive decisions and irresponsible behaviors, without demands for more responsible, adult behavior. When the consequences of this continued to mount, they reached their limit and rapidly switched to the other extreme of forcing autonomy by asking her to move out, even in her pregnant and unemployed state. Problem solving then naturally focused on finding a dialectical synthesis—a middle ground between these polarized positions. The corresponding treatment targets (see Chapter 5) of increasing individuation while decreasing excessive dependence, plus increasing effective reliance on others while decreasing autonomy, served as a guide for the therapist to help the family reach a middle path. The parents were reluctant to change their position of forcing their daughter out because of the self-destructive course they felt she was on, as well as the matter of the younger siblings’ well-being. The father stated that his limits, which could not be compromised, were ensuring the safety of his younger daughters and respecting his position that the boyfriend was no longer allowed in the house. Thus the therapist helped devise a plan that satisfied their concerns.

In a suicidal crisis involving family members, the therapist faces the challenge of enlisting the parents’ help in modifying their stance on the one hand, and not reinforcing suicidal behavior on the other. In this case, the therapist believed that the client’s suicidal behavior also had an operant component, as her parents had inadvertently reinforced her suicidal behavior in the past. The therapist thus turned to the teen and said, “So you don’t want to move out? We need to think of a way to talk to your parents about this where we take their concerns (which are realistic) into account, but where you also can get some of what you are asking for.” The burden was then on the adolescent to replace her suicidal communication with validation of and negotiation with her parents (this was an example of pulling improved behavior from the client), with the assistance of the therapist’s coaching. Also, the therapist did not encourage the parents to let her “off the hook” completely, by dropping all of their demands in response to her suicidal communication, but rather to clarify and assert their revised “middle path” demands. To clarify the contingencies operating, the therapist would then point out that the parents responded with reason and flexibility to the adolescent’s effective (i.e., nonthreatening) communication regarding the matter of conflict (thus reinforcing a reduction in suicidal communication).

The problem-solving process led to the following: The parents agreed to let the client stay temporarily in the family apartment and to provide her with partial financial support, if certain conditions were met. She would have to take a series of steps to demonstrate her commitment to becoming more autonomous, more of a contributing member of the household, and more of a role model to her siblings. These steps would include demonstrating a concerted effort to find and keep at least a part-time job, contributing to the household with income and increased responsibility for household tasks, getting appropriate health care during her pregnancy, and (most important) keeping arguments with her boyfriend out of the house. At the same time, they asked that she look into alternative living arrangements. If these conditions were not met in a month, they would not ask her to leave immediately but would give her a warning, and she would have an additional month either to meet the conditions or to move out. However, if the conditions were met, she could remain home indefinitely, with the understanding that when the baby was born, new issues would arise and would have to be negotiated. They were also willing to consult with her on finding a job and on finding other living arrangements (this was an example of the consultation-to-the-patient strategy, which helped with the treatment target of increasing effective reliance on others; see Chapters 3 and 5), rather than expecting her to accomplish these steps without help. This plan satisfied the parents, in that they felt that their daughter would either remain home under tolerable circumstances for all members, or would move out but with ample time to plan for a feasible living situation. The plan also appeased the client, because she was better able to understand her parents’ position while being relieved that they were flexible and willing to give her a chance to prove herself—which she claimed that she was motivated to do.

In addition to this broader plan, the therapist wanted to obtain commitment to a plan of action to address the adolescent’s immediate suicidal risk. Upon reassessment of the client’s suicidality, she reported no longer intending to kill herself (for now) and having more hope. It is important for therapists to err on the side of being conservative and to anticipate a recurrence of the crisis response. In this case, where family relations were likely to remain strained and where overdosing was a response that had been reinforcing for the adolescent in the past (numbing her immediate pain, arousing her parents’ sympathy and support, and relieving her of certain responsibilities), suicidal behavior seemed a likely problem-solving mechanism for this teen. Thus the therapist obtained the client’s commitment to go home and dispose of the Tylenol under her mother’s watch, and to allow her mother to keep the antidepressants locked up and administer her daily dose. In addition, she agreed to practice self-soothing and mindfulness to help her tolerate her affect if her distress should intensify, and to page the therapist prior to any self-harm behavior if suicidal urges increased. If the therapist could not be reached immediately, she agreed either to call her best friend or to skillfully approach her mother to try to enlist her support. As part of anticipating a recurrence, it can be helpful to remain in contact to monitor the teen following a crisis session. The therapist thus made a plan to check in with the adolescent by phone later that evening and the next day, and to see the family in 1 week for a follow-up session. The parents also agreed to lend additional “eyes and ears” in observing their daughter, and to prompt her to call the therapist if they observed a marked decline in her mood or behavior.

Some teens’ communications of suicidality are stated as threats (e.g., “If you don’t let me go to see Johnny, I’m gonna swallow these pills right now!”). In response to such threats, parents have often understandably given in to the teen’s demands repeatedly, fearful of the consequences. In such a case, the therapist will need to teach the parents not to reinforce the suicidal behavior, but to withhold reinforcement to work toward extinguishing it. This is difficult, especially because of “behavioral bursts” that occur (i.e., withholding reinforcement often results in an increase in behavior before a decrease begins). But a parent can be taught to use some of the very same strategies that the therapist uses in handling suicidal communications. These include dialectical strategies such as extending—in which the most extreme part of the teen’s message (the suicidal threat) is addressed, rather than the request embedded in the communication (see Chapter 3). For example, in the example of an adolescent threatening to swallow pills if she is not allowed to go see her boyfriend, she desires to see her boyfriend and wants that part of the communication attended to by the parent. In extending, the parent would attend to the more extreme part of the communication, ignoring the wish to see the boyfriend. So the parent might respond with “Oh, really? You’re planning to take those pills? Do we need to get you to the emergency room? I’ll call an ambulance.” This attention to the “wrong” part of the statement typically results in a deescalation of the extreme communication (“No, you don’t have to call an ambulance! I’m not going to take them! But you’ve got to let me go see Johnny!”)

Relatedly, there should be a matter-of-fact determination of risk by a parent, in which warmth is not increased but the parent ascertains whether there is danger. Can the adolescent commit to keep him- or herself alive? Can he or she commit to staying in contact with the parent, calling the parent or therapist before engaging in any self-harm behavior? Will the teen agree to dispose of pills or other lethal means? Does the parent’s troubleshooting indicate that the crisis plan will be followed even if the teen’s mood changes? If not, some form of closer monitoring might have to be considered. Overall, the parent must do what has to be done to keep the adolescent alive while not caving in to such threats. The parents must be reminded that temptations to “give in” in response to suicidal communications in the short run are likely to escalate suicidal behavior in the long run. Despite the fact that contact with parents during a crisis will typically occur during family sessions, some of this teaching can take place with the adolescent out of the room, if necessary. If the therapist feels a critical need to speak alone with the parents, he or she should first orient and get agreement from the adolescent: “I think at this point I can best help your parents be helpful to you if I talk to them alone for a few minutes. Are you OK with that?” A brief explanation and request to the adolescent convey respect and are likely to be met with an affirmative response. However, it may be best to avoid meeting with parents alone, to minimize risk of damaging the adolescent’s trust.

The parents and therapist face tough decisions following suicidal behavior, because the goal of keeping the client alive in the short term (and thereby intervening in a more active fashion) might appear to conflict with the goal of avoiding intensive, reinforcing attention that increases suicidal behavior in the long term (Santisteban et al., 2003) or avoiding iatrogenic treatment programs that may be administered in some inpatient settings (e.g., being coddled by staff). That is why a parent should always try to determine actual medical risk and intervene as appropriate, while resisting the urge to increase soothing and warmth or respond to the adolescent’s suicide-linked threats.

On the other hand, parents may have little idea how to determine whether a child’s talk of suicide poses a real risk. Teaching family members suicidal risk factors (Table 8.5), as well as teaching them how to listen and suggesting some follow-up questions to ask their child, can be invaluable. For example, one adolescent broke down crying in front of her mother, stating that she did not want to “be here anymore.” Her mother, anxious to find out what was going on, responded by forcefully saying, “Something must have happened! Come on, tell me what happened!” These words made the adolescent feel that she was being accused of something; they also missed the point that in her mind, no one thing had occurred, but there was an overwhelming accumulation of rejections and failures. The adolescent simply shut down, and the exchange became one more event confirming for her that she had no one she could rely on. In an ensuing family session, the therapist worked on helping the mother to see how she could have been more helpful in maintaining her daughter’s communication and finding out her actual intent. The therapist provided suggestions of more helpful responses, some of which were volunteered by her daughter. For example, her daughter wished to convey how despondent she was and wanted a sign that her mother understood her pain. The daughter stated that an initial response such as “I’m sorry to see you are in so much pain. I’m here if you want to talk,” would have made her feel that her mother cared, and she would have engaged in a conversation with her. In fact, that was the outcome the teen had been wishing for. The therapist pointed out that the mother could have then asked more about the suicidal reference and gotten a sense of whether any further steps had to be taken (e.g., obtaining commitment to a plan of action, contacting the therapist, etc.). Note that the therapist must also work with the family members to ensure that their validation and attentiveness are not primarily contingent upon suicidal communications; thus an overarching treatment goal with parents is to increase their ability to validate their teen in general. Moreover, the therapist emphasized in this case that the parent might have used mindfulness and distress tolerance skills to manage her own anxiety about her daughter’s expression of suicidal thoughts.

There may be times when parents’ interpretations of a crisis situation do not match the adolescent’s interpretations. One scenario is that the adolescent presents in crisis, but the parents minimize or negate the importance of the situation or the severity of the adolescent’s risk. This tendency can be akin to normalizing pathological behavior, as discussed in Chapter 5, and can also be part of a pattern of pervasive invalidation of the adolescent (see the discussion of the biosocial theory, Chapter 3). An example of this was an adolescent who was intensely distressed; reported suicidal ideation, clear intent, and a specific plan; would not agree to a plan to keep herself alive; and was asking to be hospitalized. Her parents brought her to the session, but asked to speak to the therapist alone for a few minutes. With the client’s assent, the therapist granted them these few minutes. They spoke of preparing the therapist for their daughter’s “dramatic behavior” and urged the therapist not to “get sucked into it.” They stated that she only wanted to be hospitalized because she missed her previous therapist, to whom she was very attached and who worked on the inpatient unit. Thus, according to the parents, the teen was inventing these symptoms because she knew “exactly how to manipulate the system” to get what she wanted. Upon assessment, the adolescent indeed expressed a wish to be hospitalized; however, she also expressed what appeared to be genuine distress, which was intensified by her perception that her parents did not take her seriously.

When a therapist encounters a disagreement between an adolescent and family members about whether something is a crisis situation or not, it is useful to remember the DBT assumption that there is no one absolute truth (see Chapter 10 for DBT assumptions). It is helpful to try to listen to both the adolescent’s and the parents’ perspectives, and at least to understand why both parties see things the way they do. The therapist should also consider the “both-and” possibility that both parties might hold a significant piece of the truth. For example, in the example above, it was true both that the adolescent missed her old therapist and wanted to see her, and that she was feeling as if she wanted to die. The therapist helped the parents to see that both positions could be true. The parents’ position made sense; even if the adolescent was honest in her denial of seeing her old therapist as her primary motive, the expectation of seeing the therapist might have nevertheless been driving her suicidal ideation and misery, since learning takes place out of awareness. However, their stance did not validate her genuine distress. As the teen’s suicidality seemed to have a large operant component, the need was to avoid reinforcing it; the solution thus would be either to hospitalize her in a different hospital, to hospitalize her in the same hospital but ensure that the old therapist would not be assigned to her, or (if possible) to develop a plan to monitor her and keep her alive as an outpatient. Note that while mental health professionals are typically trained to use hospitalization for suicidality, this choice does not necessarily best serve a suicidal client. In fact, although an inpatient stay may keep an individual alive in the short run, there is no evidence that it helps to keep one alive in the long run. Moreover, hospitalization may have iatrogenic effects, as it tends to reinforce behaviors not helpful to the client while doing little to facilitate the client’s coping with difficulties faced in the context of life outside the hospital.

In general, when searching for a dialectical synthesis between extreme perspectives, the therapist can investigate whether there is something about the way the adolescent has communicated pain that has led family members to discrepant interpretations (e.g., not asking for help when needed, asking inconsistently, appearing periodically helpless, etc.). Behavioral rehearsal with the adolescent, followed by a family session in which the teen skillfully communicates his or her experience, often helps dramatically (see Table 9.3, below). The therapist should also consider whether the discrepant view of the crisis is part of a pattern of pervasive invalidation of the adolescent. If so, stressing validation of the adolescent may help bring them together.

Another possible scenario is that parents will perceive a crisis when the adolescent does not. For example, an adolescent may appear moody, withdrawn, and uncommunicative, or may be spending excessive amounts of time with friends, and a parent may believe that a crisis situation is occurring (e.g., suicidality, a drug problem, etc.); yet the adolescent reports a lack of any particular distress or subjective change in mood or thoughts. This can also happen when a parent perceives that an environmental crisis is occurring (e.g., parental divorce) and that the adolescent must be having an extreme reaction to it. This can be akin to pathologizing normal adolescent behavior (Chapter 5) and can also be a form of invalidation, if parents reject their children’s input and do not take their statements at face value. This concern can be understandable, particularly when parents have had the experience of suicidal crises in the past and are now hypervigilant and fear missing key warning signs. But assumptions about crises can pose difficulties if the parents put excessive pressure on their child to “admit” what is going on or to behave differently, pressure the therapist to intervene in some way, or insist that the adolescent meet with the therapist (or enter therapy initially) to discuss the “problem.”

A helpful response to this scenario can be to enhance the adolescent’s empathy for the parent, in terms of both why the parent might remain concerned and how worried the parent must feel, given these concerns. The therapist can then work with the adolescent to communicate skillfully what is valid and invalid about the parent’s perceptions. For example, one mother noticed that her daughter had become moody and was spending excessive amounts of time with her friends (“I don’t know where they go. I have no idea what she’s doing out until 2 A.M., and she won’t tell me. How do I know she’s not doing drugs, or having sex, or getting into some kind of trouble?”). Meanwhile, her daughter insisted that there was “nothing wrong” and they were just “hanging out”; the more she denied problems, the more her mother challenged her. In this case, the teen was doing very well in school, was engaged in many extracurricular activities, and (according to her reports in individual sessions) was not suicidal or engaging in risk behaviors. Based on their history together, her individual therapist trusted the client’s self-report. She was, however, extremely anxious about leaving for college the following fall and felt guilty about leaving her single mom home alone. To address what the client experienced as her mother’s “constant questioning” and distrust of her, the therapist devoted individual session time to figuring out how to “get Mom off her back.” The therapist helped the client to see her mother’s perspective; given the client’s history of suicidal behavior and some ongoing family stressors, it was natural for a mother to worry about her daughter’s long absences, particularly when she was uncommunicative about anything specific she did during those times. The client resented her mother for not allowing her privacy, and so resented sharing details of her times with her friends. Yet once she understood the basis of her mother’s concerns, she was responsive to the therapist’s next question: “Now how can we get her to trust and believe you?” The client then realized that by filling in her mother to a greater extent about how she spent her time with her friends, and by admitting the primary stressors on her mind (i.e., those concerning leaving for college), her mother would feel reassured, would be able to make sense of her daughter’s behavior, and would be less apt to “nag” her. In addition, the therapist worked with the mother on observing her own limits regarding her daughter’s late nights out. By limiting her daughter’s late nights to weekends, and requesting a phone call if she were to be out past midnight, her mother felt more comfortable allowing her daughter this independent time without questioning her.

At times a therapist will find that the family members involved in a client’s treatment do not hold the same view of a crisis situation as the therapist. They may think that it is either more or less serious than the therapist considers it—or, even if all adults hold a similar view of a crisis, they may hold differing views of how to handle it. This may pose a great challenge to the therapist, particularly if it results in the family members’ not cooperating with what the therapist sees as essential recommendations. For example, parents may want to hospitalize their child immediately because of behavioral changes they observe, despite the therapist’s belief that the situation can be handled on an outpatient basis with perhaps increased contact. Or they may, in a well-meaning way, be engaging in actions that reinforce suicidal behaviors. For example, one set of parents allowed their daughter to escape from all aversive demands the moment she expressed suicidal thinking (e.g., doing homework, attending school, meeting household responsibilities). For this client, suicidal behavior became so effectively operant that it became deeply ingrained, and minicrises occurred regularly. For these parents, treatment involved pointing out the pattern and working to change the contingencies. For example, the therapist taught the parents the dialectical strategy of extending, as described earlier, so they began to respond by seriously inquiring about the suicidality their daughter expressed instead of responding to the desire to escape from a responsibility. As predicted, she then began to deescalate her communications of distress. In addition, the strategy of contingency clarification was used with the adolescent to point out this pattern to her and actually get her to begin work on reducing suicidal communications.

Conversely, parents may not see a need for any special protocol or procedures, and may adopt a “watch and wait” attitude. For example, one of our adolescent clients was voicing strong suicidal intent and evidencing emerging delusional thinking in the beginning of treatment. The client’s parents were convinced that hospitalization would cause a deterioration in functioning because of psychotropic medications (their daughter had had bad experiences with these medications in the past) and exposure to psychotic clients. The mother was actually in the medical field and held strong views based on her knowledge and experience—yet they were discrepant from the therapist’s view that hospitalization should be considered immediately. In this case, it was important that the therapist assess further to determine exactly what the parents’ concerns and the client’s past negative experiences with psychotropic medications and exposure to other clients were. Their concerns were validated, and the therapist discussed with them the compromise of communicating with the pharmacotherapist to try different medications this time. The parents were also concerned that exposure to psychotic clients would make their daughter “sicker.” Here a dialectical synthesis was sought: The therapist reassured (i.e., educated) the parents that psychotic disorders were not contagious, but validated the truth in their position—that the experience of inpatient hospitalization and forging connections with other inpatients could indeed influence their daughter’s identity, as least in the short run, as a “mental patient.” However, the experience of delusional thinking outside of the hospital setting would also be likely to make her feel like a “mental patient,” and would perhaps even be prolonged by the lack of inpatient treatment. Since the parents felt taken seriously by the therapist, they were able to engage in a continued discussion and explore options. As the parents remained reluctant to consider hospitalization, the therapist discussed alternatives with them and warned of possible consequences associated with such alternatives. For example, the therapist warned that the risk of monitoring the teen closely at home might result in a deterioration of functioning and ultimately hospitalization anyway (which could possibly be even longer, because it would begin at a more advanced point in her psychotic episode). In this case, the therapist and parents agreed to a compromise of keeping the adolescent out of the hospital for the next 24–48 hours, but going immediately for a consultation with a pharmacotherapist for possible outpatient pharmacotherapy. The plan, developed with the adolescent and the parents in the room, included moment-to-moment details on how they would monitor her and keep her from harming herself, including overnight. With the adolescent’s commitment that she would not engage in suicidal behaviors and the parents’ agreement to the plan, the therapist let them go without insisting on hospitalization. In this case, the adolescent was on a new medication 48 hours later, and the adolescent and her parents remained compliant with their monitoring plan. The delusional thinking soon remitted; the parents agreed at this point to take their daughter to an emergency room if delusional thinking reemerged.

One of the most challenging aspects of conducting DBT with adolescents is encountering such a lack of shared perspective with a client’s family members, a lack of parental cooperation, or (even worse) outright perceived parental sabotage of treatment goals or strategies. During a crisis situation, the ramifications of such mismatches can become even more serious. Just as in working with adolescents toward problem solving, the therapist may need to employ orientation, didactic, and commitment strategies with parents in responding to a crisis. There is no a priori reason to assume that parents will know just how to read an adolescent’s signals or how to respond. Thus the therapist may need to spend ample time not only on psychoeducation, but also on commitment strategies to try to understand what will interfere with the parents’ collaboration with the crisis plan (e.g., withholding certain reinforcers), as well as to shape them toward doing so.

On the other hand, unlike working with adults (where the therapist usually plays the sole expert role), working with minors necessitates considering the parents as expert consultants on their children. Although the parents may not have training as mental health professionals, and are not serving in such a capacity with their child, they certainly have expertise regarding their child and the child’s history and patterns. The therapist must thus remember not to adopt an arrogant position of “expert” with regard to his or her knowledge of the client, and instead to consider the parents’ perspective respectfully. This input from other observers in the client’s natural environment (i.e., family members) may provide invaluable information on how the client comes across to others, communicates distress ineffectively, and so on. Thus, even if the therapist does not see eye to eye with parents regarding the assessment of the situation, the therapist should pay attention to any opportunities to learn more about the client. Table 9.3 summarizes strategies for handling mismatches in perceptions of crisis situations.

In the example above regarding the adolescent with emerging delusional thinking, a careful balance of assessment, validation, taking the parents’ concerns seriously, orientation, psycho-education, and flexibility on the therapist’s part was needed to stay engaged in a productive dialogue with these parents and come up with a plan that was satisfactory to all. If the parents had not been amenable to adhering to the specific crisis plan, or in some other way could not reach an agreement with the therapist, the next step would have been for the therapist to refer them to a provider who could help them as they wanted. However, if parents insist on an intervention (or on a lack of any intervention or monitoring) that the therapist believes is absolutely a dangerous approach, given the adolescent’s presentation, the therapist may be left with no option but to report them to a child protection agency for medical neglect. Reporting for such neglect depends on state laws, and providers should be familiar with these. This is a serious step that should only be considered when it is believed that a client’s life is in jeopardy; when all other options have been exhausted; and after consultation with one’s team, individual supervisor, or other trusted colleagues.

TABLE 9.3. Strategies for Handling Mismatches in Perceptions of Crises

Finally, these issues are appropriate for bringing to the DBT consultation team, particularly to help the therapist remain reasonably balanced and empathic toward parents as well as the adolescent client. The therapist must remember that a number of factors may be operating from the parents’ vantage points that could make them either less or more likely to perceive a crisis. These include the difficulties of having an often emotionally and behaviorally dysregulated child; the pain and anxiety parents experience at believing that their child is in danger or at risk; their prior experiences of either missing real danger signs or jumping to conclusions for no reason; and the potential shame, self-blame, and fear of appearing incompetent or inadequate as parents merely because of having a child in treatment.

Confidentiality can be broken when a therapist believes that a minor client is at serious risk. Defining what level of risk is serious enough to break confidentiality, however, may not always be clear in work with adolescents and their parents. Certainly, if a therapist determines that there is a high and imminent threat of suicide, the choice to notify others (typically the adolescent’s parents) is straightforward. However, does an increase in suicidal ideation with no clear plan merit breaking confidentiality? How about increased ideation and access to lethal methods, but a denial of intent? What about the case of NSIB (e.g., self-cutting with no intent to die)? Is NSIB, no matter how minor, indicative of posing a danger to oneself when we know that individuals who engage in such behaviors are more likely to complete suicide eventually (e.g., Cooper et al., 2005)? What about other risk behaviors that have lethal potential, such as unprotected sex or drunk driving?

These are complex decisions, and must be weighed against the fact that if confidentiality is ensured, the adolescent is likely to have a higher level of disclosure to the therapist. We thus suggest a number of guidelines, which are summarized in Table 9.4. First, it is critical to explain to the adolescent and parents the limits of confidentiality (i.e., if the therapist suspects or learns that the client is at imminent risk of committing suicide or homicide, or learns of ongoing child abuse or neglect) from the outset of treatment, to avoid later feelings of betrayal. In addition, the clinician must discuss how he or she will handle confidentiality regarding sensitive issues (e.g., NSIB, risky sexual behavior, drug use). Although the therapist can stress that he or she will make a serious effort to keep sensitive material private, the therapist must emphasize that this cannot be guaranteed, because sustained intense risk behaviors or a serious escalation of behavior that puts the minor client at risk of suicide or indicates the therapy is not helping will need to be discussed with the parents (Santisteban et al., 2003). The therapist can further explain that withholding such information from parents would not only be irresponsible, but also undermine the protective function critical to parents’ roles. Having said this, however, the therapist indicates willingness to make the adolescent’s privacy a priority, and works hard both to rehearse with the adolescent how to disclose the issue him- or herself in the following session and to ensure that the family’s interaction around the material remains adaptive, if sensitive material needs to be discussed (Santisteban et al., 2003). Rather than warning a parent about an adolescent’s high-risk situation over the phone following a session with the adolescent, we might use session time to plan how and what the adolescent will communicate regarding the issue of concern, or use a family session to communicate this information (provided that essential time is not lost in doing so). In the interest of the safety of our minor adolescent clients, we err on the side of a lower threshold for determining what level of threat merits breaking confidentiality—especially in the early stages of treatment as we are getting to know the clients). But in the interest of maintaining a therapeutic alliance with each client, treating each client with respect, and following the principle of consulting to the client on handling the environment rather than consulting to the environment (see Chapter 3), we prefer to encourage clients to communicate to their caregivers about the issue of concern directly.

TABLE 9.4. Guidelines for Breaking Confidentiality

From treatment outset

Explain limits of confidentiality.

Discuss how therapist will handle confidentiality regarding sensitive issues (e.g., NSIB, risky sexual behavior).

Under these conditions, therapist does not need to break confidentiality

Legal standards for breaking confidentiality are not met (therapist must know state laws).

Therapist believes that disclosure would be likely to result in exacerbation of the crisis or place adolescent in danger.

Under these conditions, therapist might choose to break confidentiality

Even when no clear-cut case for breaking confidentiality exists (i.e., no imminent danger to self or others), therapist may elect to encourage disclosure of crisis state to a parent or other family member if:

Such a disclosure would be likely to do more good than harm.

Therapist believes that parent’s knowledge of situation would result in needed support for the adolescent.

Therapist believes that lack of disclosure would significantly interfere with client’s ability to get through the crisis.

Therapist believes that lack of disclosure is seriously undermining family work or is somehow maintaining crisis situation.

Therapist believes that holding a particular secret regarding the adolescent’s welfare is too great a violation of family trust.

Therapist sees parent as critical in monitoring and aiding the adolescent through crisis, even if therapist coaching is needed to assist the parent in being helpful.

Therapist may initiate contact with family members directly if he or she determines that shortterm gain in reporting crisis is worth potential cost of adolescent’s (1) trust and (2) learning to communicate difficulties and seek help appropriately.

Under these conditions therapist does need to break confidentiality

Behavior reaches threshold of legal mandate (i.e., suspicion) to report abuse or neglect.

Behaviors escalate significantly.

Behaviors are maintained at significant level of risk, so that:

Minor client is in danger.

Treatment does not appear to be helping.

Minor client is threatening to harm a particular person.

How to handle breaking confidentiality when adolescent agrees

Engage adolescent actively in process.

Inform adolescent about therapist’s plans.

Allow adolescent to voice concerns.

Plan with adolescent how, when, and to whom the disclosure will take place.

Use behavioral rehearsal to plan disclosure.

How to handle breaking confidentiality when adolescent does not agree

Engage adolescent actively in process.

Inform adolescent about therapist’s plans.

Explain rationale; communicate directly about intentions.

Allow adolescent to voice concerns.

Be sure to understand the adolescent’s perspective (can conduct behavioral analysis of unwillingness to disclose if becomes therapy-interfering behavior).

Discuss pros and cons of disclosing.

Discuss potential consequences of not disclosing.