This chapter is organized around the conduct of an individual therapy session. We cover strategies for beginning sessions, for targeting Stage 1 treatment priorities, for carrying out those treatment priorities in midsession, and for ending sessions. Later in the chapter, we also describe how individual therapists conduct telephone coaching with their clients. All DBT strategies are employed in individual therapy, making this modality the most challenging to deliver competently. Good training in DBT, individual supervision, and intermittent observation of tapes by one’s consultation team or individual supervisor all help to ensure adherence to the treatment model.

The individual therapist is the primary therapist in outpatient DBT. He or she is responsible for increasing the adolescent’s motivation, inhibiting maladaptive behaviors, increasing the adolescent’s skillful behaviors, and generalizing them outside the therapy setting. In settings where there may not be an individual therapist (such as juvenile justice), one staff person needs to be designated the primary therapist and to be responsible for conducting behavioral analyses and for making the final decisions about the treatment plan; hence all other modes of treatment (e.g., skills training, family therapy, pharmacotherapy) revolve around the primary therapist.

One of the biggest challenges for the individual therapist is that many multiproblem suicidal adolescents have emotion phobia. Thus they tend to avoid content that induces affect in session in a variety of ways, including shutting down, attacking the therapist, or not coming to sessions in the first place. These therapy-interfering behaviors can make individual therapy with an adolescent extremely challenging. Once the teen arrives, however, the individual therapist employs a variety of strategies.

Initially, many adolescents dread coming to sessions. They fear that they will get reprimanded for “bad” behavior or will be “forced” to talk about painful events; either, they believe, will inevitably make them feel worse. Moreover, they do not believe that their problems can be solved, especially by adults whom they barely know. Starting sessions in a fairly routine fashion fosters a predictable structure for an adolescent and helps reduce anxiety and fear. The following is a useful sequence of strategies for beginning a session: (1) greeting the client; (2) reviewing the client’s diary card and/or handling diary card noncompliance; (3) discussing the plan for the session; (4) recognizing and, if necessary, targeting the client’s current emotional state; (5) reviewing individual therapy homework assignments (if given); and (6) checking progress in other modes of therapy.

With any client, but particularly with an adolescent, the therapist must communicate early in the encounter a feeling of warmth and caring toward the client. Whether this is done with a genuinely warm smile and a “Hello,” a “Hey, what’s up?”, or some variation of a handshake (e.g., a high-five), the therapist must make the client feel welcomed each week—even when the therapeutic relationship has been strained by therapy-interfering behaviors. Adolescents often carry the expectation that if a problem with an adult has developed, it is unlikely to be resolved. The therapeutic relationship is no different until proven different. Even when a client has missed the last session, the therapist may want to comment on how good it is to see the client again before discussing the agenda and determining what interfered with his or her attending the last appointment.

After greeting the client, the therapist asks for and reviews the diary card (as described in Chapters 6 and 7). Frequently, after the first few weeks of the therapist’s asking, “Do you have your diary card?” the client becomes conditioned and generally hands over the diary card without being asked. A common mistake by DBT therapists is waiting too long to ask for the diary card or forgetting to ask for it altogether. When this happens, therapists inadvertently communicate that the diary card is not important. Hence they should train themselves and their clients to review the diary card immediately following the greeting. The diary card informs the remainder of the session. If a client fails to bring in the diary card or has not completed it, the therapist asks the client to fill out a blank card in session or complete the unfinished one. The therapist’s message is clear: “We cannot continue the therapy session until we have a completed diary card in hand.” Potentially serious problems arise when the therapist forgets or chooses not to attend to the diary card early in the session. For example, imagine the scenario of a therapist’s focusing on employment issues, only to discover—with 5 minutes left in the session and another patient waiting—that the client engaged in life-threatening behavior yesterday.

The first time the client fails to turn in the diary card, the therapist responds nonjudgmentally and asks, “What happened?” Regardless of the response, the therapist is likely to say, “Remember, we cannot proceed in the individual therapy session without a completed diary card. So I am going to ask you to fill out this blank one, and we’ll talk when you are done.” The therapist should then start doing some deskwork and refrain from interaction with the client as he or she fills out the card. If there is a specific question about how to fill out the card, the therapist should respond accordingly. However, if the client wants to talk through issues that are being noted on the diary card, the therapist should encourage the client to complete the diary card before the two of them engage in any further discussion. At the start of therapy, however, the therapist often helps the client fill out the card. Sometimes clients are unable to fill out the card when they are acutely suicidal or emotionally overwhelmed.

If the client fails to bring in the diary card a second time, the therapist treats this as therapy-interfering behavior, conducts a detailed behavioral chain analysis and solution analysis, and may also choose to apply a slight aversive consequence. For example, when the client acknowledges that he or she forgot the card, the therapist hands a blank card to the client, turns away from the client, gets involved in some deskwork, and says, “Let me know when you’re done.” This makes continued interaction contingent upon filling out the card. Yet, behavior analysis is a crucial step for understanding the factors that may be interfering.

Another approach is the therapist’s use of DEAR MAN interpersonal effectiveness skills (see Table 4.2 and Linehan, 1993b). Obviously, it is most effective when the client has been exposed to this skill set in group already, but it can be effective nevertheless if the therapist asks the client to turn to this skill in his or her notebook and they review it together for a moment. For example, one DBT therapist chose to use DEAR MAN skills with one of his adolescent clients whose history included dropping out of high school 2 years earlier, never doing her homework when she attended school, and (after 5 weeks of DBT) exhibiting consistent noncompliance with her diary card. He said, “T., I am not sure what else to say or do right now. I feel as though we have exhausted all problem-solving strategies to get you to bring in your diary card each week, and nothing seems to work. So I am going to use my best DEAR MAN skills and hope that I can get you to change your behavior this way.” The therapist then went through the DEAR MAN sequence as follows:

Describe: “T., for the past 5 weeks you have not been able to bring in your diary card. I know you never liked doing homework at school, and from what you have told me, in some ways the diary card feels the same to you. Unfortunately, without the diary card, I am limited in my ability to help you, and it really interferes in our ability to work on other things that you want to work on.”

Express: “I feel disappointed and frustrated, because I feel unable to convey to you the importance of completing and returning the diary card each week. I actually begin to feel less effective as a therapist, and I am worried that the treatment will not be successful.”

Assert: “So, I really want you to do everything in your power to make the diary card a top priority—not for me, but for yourself.”

Reinforce (reward): “You have told me that coming to therapy has already started to help you, and I am so glad to hear that. I can tell you are dedicated to helping yourself feel and do better, and I respect and admire you for that. T., I really have enjoyed working with you, I like you, and I truly feel like we could work so much better together if you could jump this hurdle that has begun to block your progress. I want to be able to trust you when you tell me, ‘OK, I will definitely do it this week.’”

Mindful Stay: In this step, a therapist should stay focused on the issue, repeating whatever is necessary like a broken record; if the client brings up other issues that may divert the conversation, the therapist consistently brings the conversation back to the issue at hand. This was what T.’s therapist did.

Appear confident: This step is self-explanatory.

Negotiate (if necessary): “What do you think? Does this make sense? Does it seem reasonable?” If a client says it is too difficult, a therapist should negotiate the issue appropriately. “Then what if you completed the top portion of the diary card this week, and filled it out completely the following week?”

The therapist’s effective application of DEAR MAN skills worked with T., and it has influenced other adolescents who until a certain point in treatment had not brought in their diary cards. It helped that this therapist had already known this client for 5 weeks and had already established a strong alliance. Trying DEAR MAN after only one or two sessions might have proven less effective.

In some special cases, exceptions to reviewing the diary card are made—at least in the beginning of treatment. For example, one of us conducted an entire therapy around diary cards with an 18-year-old client. The client’s “noncompliance” with the diary card was emblematic of most other aspects of her life in which she was unable to get herself to do things that were new and difficult. Thus, instead of requiring her to fill out the diary card in session, the therapist conducted behavioral analyses and addressed the emotions and skills deficits that impeded her functioning.

With an adolescent, it is critical for the therapist to discuss the agenda early in the session, albeit in a relaxed and flexible manner. This ensures that sufficient time is allotted to discuss the higher-priority issues. Many multiproblem suicidal adolescents appear relieved to have a flexible outline of topics to be discussed. This helps alleviate some anxiety as to whether specific topics will or will not be addressed and why. To help organize what could otherwise be a chaotic and disorganized session, a therapist follows the DBT Stage 1 target hierarchy. As discussed in earlier chapters, this hierarchy starts with decreasing life-threatening behaviors, followed by decreasing therapy-interfering behaviors, decreasing quality-of-life-interfering behaviors, and increasing behavioral skills (in that order). If the client refuses to cooperate with the topics’ being discussed according to the target hierarchy, this refusal is considered therapy-interfering and is addressed accordingly. Therapists who do not flexibly adhere to the DBT target hierarchy for whatever reason are not adhering to DBT and need to present this problem in the therapist consultation meeting as “therapist treatment-interfering behavior.” For both the client and therapist, the issue here is not so much the order of discussion as it is the importance of addressing certain topics during the session.

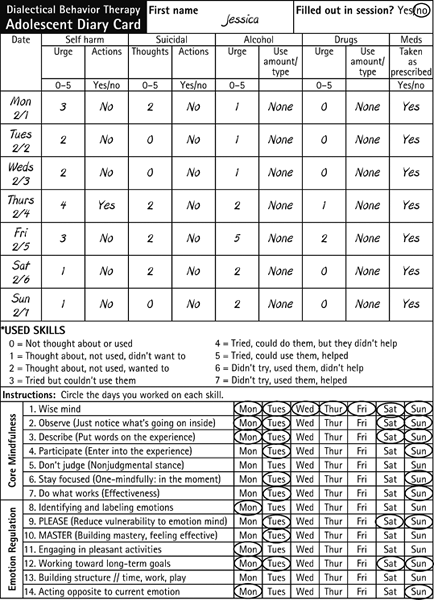

To organize the agenda, the therapist reviews the diary card aloud while mentioning which target behaviors appear to warrant discussion. If the client does not volunteer any items for the agenda, the therapist should ask in a collaborative tone whether the client has any other items to put on the agenda. This fosters a sense of openness and mutuality, in that each member’s agenda is known to the other, and therefore each one knows what will be discussed and in what order. As the therapist reviews the diary card aloud, he or she offers positive reinforcement for any target behaviors that are diminishing, while also highlighting any target behaviors that appear to have worsened and putting them on the agenda to be discussed next in hierarchical order. Jessica’s diary card, some weeks into treatment, is seen in Figure 8.1. The therapist reviewed it aloud as follows:

“Jessica, I am so glad you completed your diary card this week before coming to session. That will leave time for some other things you’ve been wanting to discuss with me, like your relationship with your boyfriend, your sister, and school stuff. So let’s take a look at your card.…I see you had low urges to use alcohol except on Friday, when you wrote down a 5. The really good news is you didn’t let your urges control your behavior, since it appears you had nothing to drink that night, right?” [Jessica: “That’s right.”] “Great! So let’s make sure we talk about those increased urges for today, and let’s also take note how you managed not to drink when your urges were that high.…I see at the bottom of your diary card that on Friday you used pros and cons, as well as the ACCEPTS skills, and rated them a 5. That is, you thought about the skills, you used them, and they helped. Were those skills used to manage your urges?” [Jessica: “Yes.”] “Great work! I also see you were compliant with your antidepressant medications. Now you also had low self-harm urges with the exception of Thursday, when you wrote down a 4, and I see you harmed yourself that night (therapist’s tone becomes neutral). What did you do?” [Jessica: “I cut myself.”] “With what?” [Jessica: “My razor blade that I keep in my room.”] “Well, this will be the first thing we discuss this evening. Let’s finish reviewing the diary card first. I see you had low suicidal urges all week. I’m glad to see there were no suicidal behaviors, though. The incident with the razor blade was not suicidal?” [Jessica: “Right, that was my usual self-harm.”] “You cut school on Wednesday, and you had risky sex that day as well. As I look at your emotions, it seems like you were not particularly angry until Wednesday. On Thursday you had a lot of sadness and anxiety. And then on Friday, you wrote 5 for shame. We will see if some of these emotions triggered some of these behaviors, or whether they were consequences of the behaviors, or both.…Is there anything else you want to put on the agenda before we start?” [Jessica: “No, that’s plenty for today.”] “OK, so let’s start by doing a behavioral analysis of your self-harm.”

FIGURE 8.1. Jessica’s diary card.

Therapists must also remember to insert into the agenda any therapy-interfering behaviors that have occurred in the past week, such as coming late to sessions (either individual therapy or skills training) or forgetting to bring in the diary card. For example, in the subsequent week’s individual session with Jessica the therapist stated while setting the agenda: “Jessica, I’m glad to see that you didn’t engage in any self-harm this week, nor did you use any alcohol. The problem is that you were 20 minutes late today, so we need to start with that so we can get you here on time. I do want to hear how you’re using these skills and coping with your problems differently. Also, since you were late, I hope we have time left to talk about your conflict with your boyfriend.”

As highlighted by the statement “since you were late, I hope we still have time left to talk about…,” the therapist makes use of an opportunity for contingency clarification. Also, by reviewing the diary card out loud, the therapist reminds the client of the target hierarchy and the customary order in which problem behaviors need to be addressed.

It is helpful to recognize the client’s current emotional state when discussing the agenda at the beginning of the session. Some adolescents report that they have nothing to add to the session agenda, but their affect indicates otherwise. The therapist may suggest to such a client, “you look upset. If there is something on your mind, it may be something to place on the agenda.” Placing items on the agenda does not mean there will always be time to address them, however. Especially in the early stages of therapy, a client’s quality-of-life-interfering behaviors (e.g., bingeing, alcohol use, interpersonal problems) inevitably get less attention than life-threatening and therapy-interfering behaviors do.

Sometimes an adolescent’s negative emotional state is related to a problem in the therapeutic relationship. As with the other relationships adolescents have, the therapeutic relationship is not exempt from challenges and strains. As a result, it is crucial that the therapist be sensitive to problems that arise within the relationship and, with few exceptions, attempt to repair the relationship early in the session before engaging in other work. Without a stable therapeutic alliance, the “therapy” is moot. Of course, relationship repair should not replace targeting high-priority behaviors within the session, which may inadvertently reinforce the client’s discussing problems in the therapeutic relationship. If the therapist is upset or having negative feelings about the client and is unsure how to broach them, sometimes it is necessary for the therapist to use the consultation group first to discuss those feelings before airing them to the client. The dialectical bottom line is this: Therapists should target the current emotional state, if necessary, and then shift back to the other target behaviors as quickly as possible.

Individual therapists sometimes assign their own homework (in addition to the diary card) beyond that assigned weekly in the multifamily skills training group. The job of the individual therapist is to drag out new behaviors, and relevant exercises function to achieve that goal. These exercises are typically assigned at the end of the prior session and must be reviewed at least briefly at some point during the next session. These questions and answers may take as little as 20 seconds and often not more than a couple of minutes. In contrast to the predetermined practice exercises assigned in the skills training group, homework in individual therapy is based on the particular client’s issues arising in a particular session. For example, when Jessica reported poor sleep hygiene during the past week, the therapist assigned her to practice her PLEASE skills during the upcoming week and report back next session. The S in PLEASE represents sleep, which implies employing good sleep hygiene (e.g., going to bed and waking at regular times, not drinking caffeinated beverages, stopping naps, and engaging in a relaxing activity before bed). For a client who may regularly engage in self-invalidation, the therapist may ask the client to track self-invalidating thoughts on his or her diary card for homework. Another therapist may assign an anxious client the task of practicing diaphragmatic breathing or engaging in specific exposure exercises, such as initiating a phone call with an acquaintance. At still other times, the assignment may involve problem solving or talking to Mom about an important issue. The point here is that an individual therapist should assign practice exercises that are relevant to a specific client at a specific moment in time in order to drag out new behaviors each week, if not each day. As in all behavior therapies, the DBT therapist must remember to ask about the previously agreed-upon homework assignments during the session. Not asking communicates that no real importance is attached to doing the homework. Thus the therapist (1) decreases the likelihood that the client will do the next homework assignment and (2) can assume more of the responsibility for the client’s noncompliance.

Because the individual therapist is the primary therapist, this therapist must oversee all other modes of therapy. In DBT, clients can only have one primary therapist, and they cannot be in other forms of treatment simultaneously (e.g., psychodynamic psychotherapy) in which they have “another” primary therapist. In each session, the individual therapist should briefly check progress in the other modes of treatment. The individual therapist often asks about the multifamily skills training group (including the homework assignments), medication appointments, and so forth. If the client is having trouble completing skills training homework, the therapist examines the problem. If it is a matter of the client’s not understanding the skills sufficiently, the therapist teaches the skill in more depth, linking the skill to the client’s current life. If the client is feeling dissatisfied with skills training and unmotivated to practice the skills outside of group, the individual therapist reviews commitment strategies and helps the client recommit to change (see Chapter 7).

The individual therapist must always consider the timing of targeting specific issues. For example, if during a behavioral analysis regarding self-cutting it comes up in an unrelated way that the client went to skills training group but did not understand the material taught, the therapist may merely highlight that there needs to be further discussion regarding skills, but that they will address it later. However, if during a behavioral analysis regarding self-cutting the client mentions she did not understand the distress tolerance skills being taught in group, the therapist might take the opportunity while weaving in the solution analysis to teach a brief lesson on a distress tolerance skill (e.g., distract with ACCEPTS; see Linehan, 1993b) and ask the client to practice that skill during the next week. In this case, the skills deficit is relevant in dealing with the life-threatening behavior being discussed. The client’s not attempting to complete her skills training group homework is considered a therapy-interfering behavior. The therapist might conduct an independent behavioral analysis of the therapy-interfering behavior once the life-threatening behavior has been analyzed.

By failing to ask about progress in other modes of treatment, the therapist communicates to the client that the other modes are not as important. If the client fails to attend or cooperate in other modes, it is the responsibility of the individual therapist to treat the behavior as therapy-interfering and analyze the problem. In particular, having an ancillary psychopharmacologist can become problematic with noncompliant teens; thus it may be helpful to construct the contingency that the attendance policy is the same for their medication visits as it is for skills training. The therapist can argue that both modalities are intended to enhance the client’s capabilities. By only adhering to the attendance policy with regard to skills training and individual therapy, the treatment program staff may inadvertently communicate to clients that their medication compliance is less important.

Setting the agenda, as described earlier, is a method to identify high-priority target behaviors and so determine the individual session’s focus. The problem is that many adolescents do not want to discuss these target behaviors, and this forces a therapist to “toe the line” against a client’s wishes. The therapist must believe in attending directly to high-priority behaviors and resist the client’s pressure to attend to other topics. This avoids the risk of inadvertently reinforcing the client’s dysfunctional behaviors (e.g., refusing to speak, attacking the therapist verbally, throwing a tantrum, etc.). We recommend that the therapist focus on long-term gain rather than short-term peace during the session. This may require the therapist to use his or her own crisis survival skills. The key is to continue moving the adolescent toward discussing the high-priority behaviors while simultaneously validating and soothing his or her discomfort as the therapist proceeds. In one case, after a client stated she would rather not discuss her recent suicide attempt during session, the therapist responded with the following:

“I know you’d rather not talk about your suicide attempt, since you mentioned that it stirs up a lot of negative emotions, and who wants to talk about such difficult things [validation at Levels 2 and 3; see Chapter 3]? You also remember, though, that any time someone has engaged in life-threatening behavior, it takes priority over other issues. How could it be otherwise? We have to figure out what happened last week that resulted in your trying to hang yourself. Any problem that leads you to want to die is a really serious problem! If you end up dead, what point would there be in our talking about any other problems you want to discuss? I’d like to be able to discuss other things as well that will help you build a life worth living. But first we have to be sure you have a life to build on.”

Over time, the client learns there is no way to avoid discussing these target behaviors, and either the resistance behaviors eventually remit or the client becomes more willing to discuss them in session.

The “meat” of the session begins as the therapist addresses the agenda item with the highest priority. For Jessica in the session described earlier, this meant addressing her self-injurious behavior identified on her diary card at the beginning of the session (see Figure 8.1). Adolescent dysfunctional behaviors, including suicide attempts and NSIB, are considered faulty solutions to problems in living (Linehan, 1981); thus problem-solving techniques are the core DBT change strategies (see Table 8.1). However, without therapist acceptance strategies such as validation of those problems in living, the adolescent will have no hope or motivation to change. To be effective, DBT requires the individual therapist to weave together acceptance and change strategies throughout all treatment sessions. With change comes acceptance, and with acceptance inevitably comes change. The therapist must also utilize dialectical, stylistic, and case management strategies with adolescents to help keep the therapy palatable and moving.

If an incident of self-injury is a faulty solution, the first challenge for the therapist is to help the adolescent clearly articulate the problem that occasioned the “solution” of self-harm. This is the first step of the problem-solving process outlined below. Behavioral chain analysis, together with validation, is used to build awareness and acceptance of the problem. The second step is for the therapist is to determine which solutions and change procedures should be applied to this specific client, at this moment, for this particular problem. That process too is outlined below.

TABLE 8.1. Midsession Problem-Solving Strategies in Individual DBT

Task: Identification and acceptance of the problem

Primary method: Behavioral chain analysis

Identify the problem.

Describe the problem in behavioral terms.

Reconstruct the sequence of environmental and behavioral events (variables) leading up to the problem, co-occurring with it, and following it:

Vulnerability factors

Precipitating event(s)

Each emotion

Each thought

Each action

Each environmental event

Pinpoint the actual prompting event(s). For suicidal behaviors, these are likely to be intense or aversive emotion states; they may also involve a lack of behavioral skills or of dialectical thinking.

Identify the environmental and behavioral consequences (contingencies). (Where are the reinforcers?)

Foster insight by highlighting recurrent patterns, and by pointing out contingencies and reinforcements.

Construct and test hypotheses about what generates and maintains the problem behavior. Where are the links that could break the chain? Where are the targets for intervention?

Provide brief didactic instruction on relevant topics as needed.

Task: Generating alternative solutions

Primary method: Solution analysis

Identify points of interventions.

Brainstorm solutions. Encourage long-term versus short-term solutions.

Evaluate solutions in terms of expected outcomes.

Choose the solution most likely to be effective.

Troubleshoot solutions.

Obtain commitment to practice new solution.

It is important to note that these problem-solving “steps” are not always done in sequence. In fact, as a clinician becomes more facile at conducting these analyses, as well as more familiar with the client’s behavioral patterns, these “steps” can be woven together. In the next section, we describe behavioral chain and solution analyses, using another example from Jessica’s treatment.

The first step in changing problematic behavior in DBT is to identify the variables that control the behavior. If more than one instance of the target behavior has occurred, then the most severe and best-remembered instance is chosen. The therapist and the client then develop a complete account of the chain of events that led to and followed the problematic behavior. As the behavioral chain analysis1 proceeds, the therapist looks for controlling antecedent and maintaining variables. He or she also tries to identify each point at which an alternative behavior could have kept the problem behavior from occurring. The detail obtained in a good chain analysis is similar to that of a movie script. In other words, the description of the chain provides enough detail that one would be able to visualize it sufficiently to replicate and reenact the sequence of events. Table 8.2 offers guidelines for a behavioral chain analysis.

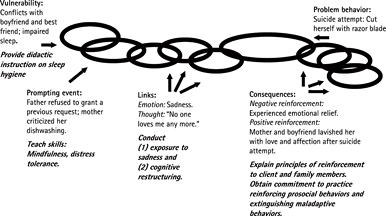

As an example of a behavioral chain analysis, we present the work done by Jessica and her therapist on an incident of self-cutting that had actual suicidal intent (not the NSIB in Figure 8.1). The therapist began by stating, “I see you made a suicide attempt on Saturday. As we have done before, let’s review what happened—including things that may have made you vulnerable, what may have precipitated this behavior, and the thoughts and feelings that are potential links in the chain that led to your suicide attempt. And, of course, we have to review the consequences of your behavior.” Jessica reported that two days before her suicide attempt, she had had a conflict with her boyfriend that resulted in a near-breakup (vulnerability factor). She reported already having sleeping problems previously and then being awake all night in a distressed state (vulnerability factor). One day later (Friday), Jessica’s best friend, Tanya, had told Jessica that she had to choose between Tanya and her boyfriend. Jessica was shocked and hurt that her so-called “best friend” was putting her in this predicament (vulnerability factor). The therapist, listening intently, responded, “Wow, what a situation! What did you say? [Level 1 validation]?” Jessica responded to Tanya with anger: “No, I wont do that!” She wanted to discuss Tanya’s actions with her boyfriend, but he “blew me off to go out with his friends instead.”

Jessica felt rejected and alone. She reported trying to indirectly obtain support from her mother and father (who had dropped by the house for a visit) by spending time with them in the kitchen. Her father reportedly told her that because of her declining academic performance, he was not going to buy her the special shoes in Puerto Rico that she had requested. While Jessica began to “contribute” (DBT distraction skill) by cleaning the dishes, her mother became extremely critical of her less-than-thorough dish cleaning. Jessica reported in a shameful posture and tone, “When my mother turned on me and started criticizing me for no reason, I wanted to kill myself because I felt upset, like no one loved me any more.” The therapist asked, “Can you define ‘upset’?” Jessica stated, “I don’t know, just upset.” The therapist paused to consider whether it made sense to pursue further questioning on clarifying her emotion, and then decided to continue: “And when did the thought ‘No one loves me any more’ occur? Before or after you felt upset?” “Before,” she said. The therapist went on, “Do you think you felt sad?” “Yes,” Jessica replied. The therapist reflected, “Sounds like after your best friend and your boyfriend blew you off, and then your mother and father became critical, you really felt sad and thought of yourself as unloved by everyone [Level 2 validation]. I can imagine most people would feel really sad, and even disappointed or angry, after a series of interactions like you had with the closest people in your life [Levels 3 and 5 validation].” The therapist then asked whether this was the first moment Jessica thought about suicide, and the client acknowledged that this was the precipitating event. Although she was unable to clearly identify her emotion in the moment, other than “upset,” the critical link (to her suicide attempt) in the chain appeared to be the thought “No one loves me any more.” Jessica reported the urge to flee the situation and to kill herself. The therapist stated, “We know from your past behavioral analyses that for you, thinking you are unloved is intolerable, and you desperately try to escape it even if it means killing yourself [Level 4 validation].”

At this point in the incident, Jessica immediately left the kitchen and chose to go to the bathroom, where she kept her razor blades. She locked the bathroom door, began to cry, and reached for the razor blade in the shower, which she then used to cut her arm several times. She immediately experienced some sense of relief (negative reinforcing consequence) after she began to cut herself. She got into her bed, where her arm left bloodstains on the sheets. In the morning, her mother went to wake her up and found her bloody sheets. Alarmed, her mother asked what had happened; Jessica replied, “No one loves me.” Jessica’s mother proceeded to tell Jessica, “I love you very much! How about after school today you and I will go shopping?” (positive reinforcing consequence for cutting and for leaving blood on the sheets). Jessica smiled and agreed to go. When she went to school and saw her boyfriend later that morning, Jessica told him what had happened. Her boyfriend expressed his love to her and asked her to go out that night, which Jessica happily agreed to do (positive reinforcing consequence). During the school day, Jessica experienced increasing amounts of shame for cutting herself; she was very ambivalent about the “love” she was receiving after the incident, but did not say or do anything about it. The therapist commented, “It sucks that you receive the most love and affection from your boyfriend and mother after you attempt to kill yourself instead of before. They have no idea that they are positively reinforcing your suicidal behavior. I’d think you’d be a lot better off if we could switch the order around, don’t you [Level 6 validation]?”

In sum, the individual therapist skillfully weaves problem-solving and validation strategies together in constructing a behavioral chain analysis. Figure 8.2 illustrates the chain analysis of Jessica’s suicide attempt.

The therapist generates and tests hypotheses about potential controlling variables as the chain analysis is conducted, and summarizes these in a problem definition that makes it clear how the behavior/event is dysfunctional with respect to the client’s long-term goals:

“Jessica, did you first think about cutting yourself when you had the thought ‘No one loves me any more?’” [Jessica: “Yes.”] “That thought—‘No one loves me any more,’—is clearly a problematic thought, don’t you think? We are going to spend some time teaching you how to challenge that thought when it pops into your head, so that it doesn’t lead you down the path to self-harm. I’d also like to work with you on ways to tolerate the intense distress set off by that remark without trying to kill yourself.”

FIGURE 8.2. Behavioral chain analysis of Jessica’s suicide attempt.

In addition, reminders of contingencies are helpful at this point. For example, the therapist might say to Jessica,

“Cutting yourself to the point that you are being hospitalized is screwing up your entire life, even though, unfortunately, cutting yourself is really effective at reducing your intense emotional pain [Level 5 validation]. Unfortunately, at the moment you can’t resist these impulses and stop this behavior, because you don’t yet have the necessary emotion regulation and distress tolerance skills to accomplish the task [Level 4 validation].”

Some strategies are used to highlight recurrent patterns across instances of targeted problem behaviors. The therapist observes and describes recurrent patterns, and comments on the implications of the client’s behavior. For example, Jessica had a general pattern of cutting when she thought she was being rejected or was “unloved.” The other problem pattern was receiving positive reinforcement from her loved ones after she cut herself. Jessica needed to receive validation and support before she harmed herself; instead, Jessica would often get the most love, attention, and affection after engaging in self-harm. This pattern was openly discussed in session. At other times, the DBT therapist may highlight a problem during session without addressing it further in the moment. For example, it became clear during the behavioral analysis that a problem with Jessica’s best friend needed to be addressed at some point. Instead of continuing in that direction at that moment. the therapist chose to highlight it briefly instead and said, “Wow, Jessica, I can see why you felt so hurt in response to Tanya’s ultimatum [Level 5 validation]. Your relationship with her has always been very intense. We’ll come back to that later. OK, keep going….”

Didactic strategies include presenting information (research findings or psychological or biological theories) to the client or her family. The purpose is to counter self-blaming morality- or mental-illness-based explanations of problem behaviors. This may happen briefly during the chain analysis or afterwards. For example, after determining that sleep disturbance was a vulnerability factor in Jessica’s chain analysis, the therapist provided a brief didactic lesson on sleep hygiene (Williams, 1993), oriented her to the potential benefits of beginning such a program, and then obtained a commitment to try it during the upcoming week. Jessica was quickly instructed to stop napping during the day, to decrease her caffeine intake, to create a soothing bedtime ritual that included reading, and to wake up and go to sleep at regular times each morning and night. She agreed to attempt her new sleep routine and wrote down the assignment.

The second phase of problem solving requires the therapist and client to generate possible solutions for the difficulties pinpointed by the behavioral analysis as described above. Together, the therapist and client must ask, “What solutions other than the target behavior could be applied to the problem at hand?” More specifically, the therapist looks for different points in the behavior chain to intervene, and there are many possible places to intervene. For example, solutions can target any potential vulnerability factors (such as the sleep factor mentioned above); the precipitating event; key links such as specific cognitions, emotions, and behaviors; and specific contingencies that may be maintaining dysfunctional behavior, as well as extinguishing or punishing adaptive behavior. The therapist helps the client generate alternative solutions, encouraging the use of long-term over short-term solutions.

Alternative solutions to the client’s problem, and the tools to implement them, can usually be found among a variety of empirically validated technologies. The most common of these change procedures fall into four categories: (1) skills training, (2) exposure, (3) cognitive modification, and (4) contingency management. When conducting a solution analysis, the therapist must consider all change procedures available. One of the many challenges for the individual therapist is to prioritize these possible strategies quickly, from most to least relevant to the target behavior. Tips for selecting change strategies are offered in Table 8.3.

Based on information obtained from Jessica’s behavioral chain analysis, the therapist selected strategies from all four main types of change procedures (see Figure 8.3). In addition, the therapist felt that a family therapy session was warranted. Jessica first felt rejected, abandoned, sad, and hurt by her best friend and her boyfriend, only to feel disappointed by her father and criticized and hurt by her mother. That precipitated the thought “No one loves me any more.” Jessica and the therapist identified the cognitive link “No one loves me any more,” and further identified the emotions of sadness as leading to her first thought of suicide. A review of the four change procedures follows below.

Skills training strategies are called for when a solution requires skills that are not currently in the client’s behavioral repertoire, or when the client has the components of a skilled response but cannot integrate and use them effectively in the moment they are needed. Skills were deemed useful in targeting one of Jessica’s vulnerability factors (lack of sleep) and the precipitating event (i.e., her reaction to her mother’s criticism) as identified in the behavioral chain analysis. It was determined that when Jessica was in distress, she had two options: (1) She could avoid her mother, given her mother’s tendency to invalidate her; or (2) she could directly express her feelings to her mother, so that her mother would know that she was in distress. The problem with the latter option was that Jessica was often unaware of what she was feeling. Thus the recommended solution for Jessica was to practice identifying and labeling emotions when she was not in distress, in order to prepare her for future episodes of emotion dysregulation: “Jessica, before you can choose a coping strategy, you need to know what you are feeling.” In addition to this emphasis on mindfully identifying and labeling emotions, Jessica and the therapist identified adaptive skills that could be used to achieve a sense of relief, such as distraction and self-soothing. For example, Jessica agreed to watch her favorite comedy video or take a soothing bubble bath when she was feeling abandoned or “like no one loves me.”

TABLE 8.3. Tips for Selecting Change Procedures for Problem Solutions

| Change procedure | Useful when: |

|

|

| Skills training | Client lacks skills needed to solve the problem or doesn’t know how to use them effectively. |

| Exposure | Client’s emotions and associated action tendencies interfere with effective use of coping skills. |

| Cognitive modification | Client’s faulty beliefs and assumptions inhibit effective coping abilities. |

| Contingency procedures | Client lacks motivation despite knowledge of skills. |

|

|

FIGURE 8.3. Solution analysis of Jessica’s suicide attempt.

Although most exposure therapies target fear as the primary emotion (e.g., in treating specific phobia, PTSD, or panic disorder), DBT expands the list of targeted emotions to include shame, guilt, anger, sadness, and other emotions that are experienced as aversive and interfere in the client’s life and/or treatment through avoidance of those emotions. In particular, shame may play a key role in suicidal behavior in women with BPD (Brown & Linehan, 1996). It is often a target for informal exposure in DBT sessions. Linehan (1993a) notes that the natural action tendency associated with shame is hiding; thus the DBT exposure procedure involves directing the client to discuss the shameful experience while not hiding (both literally and through postural expressions).

For example, with Jessica, before beginning exposure to feelings of sadness, the therapist chose to address the feeling of shame that she displayed as she recounted her suicide attempt in session. The therapist encouraged actions opposite to shame by being persistent and soothing; he also reminded Jessica as needed to look the therapist in the eye, to sit up straight, not to mumble, and not to change the topic. Often during informal exposure, a client will begin to discuss what is shameful and then interrupt him- or herself. One metaphor (dialectical strategy) Jessica’s therapist used to try to get her to stop such interruptions was that of jumping off a high diving board:

“Telling me something you’re ashamed of is like a novice diver walking slowly to the edge of the high diving board 20 feet up in the air and looking down.…What happens? The diver becomes afraid and wants to turn around and climb back down the ladder. The only way that the diver is going to feel comfortable up there is to run off the board without looking down. The same thing is true for you: Keep telling me your story without stopping and ‘without looking down.’ I will have you tell it to me again and again until you can just spit it out without stopping and without your body getting into the ‘ashamed’ body posture (briefly mimics Jessica’s body posture) it gets into when you feel that way.”

After this targeting of shame, the next intervention with Jessica was to conduct formal exposure exercises to her sadness. Jessica’s sadness often precipitated impulsive behaviors and distorted cognitions. “Jessica, it is important for you to be able to experience sadness as not dangerous and requiring escape. The better able you are to sit mindfully with your sadness, the less likely you will be to turn to your maladaptive coping strategy of suicide and self-injury.” These exposure exercises took place during significant portions of the subsequent three sessions. Exposure is a very important part of treatment used with a variety of target behaviors. For example, with a client whose eating is disordered, the therapist might bring tempting foods into session and have the client watch urges to binge or purge. For a client who is apparently unable to tolerate high anxiety and panic, the therapist teaches the client to mindfully observe and describe the anxiety until the client habituates to the emotion and no longer feels the urge to escape from it. Often in DBT sessions, the therapist asks the client, “Where in your body are you feeling an emotion? Now just observe it.”

One important distinction between DBT and cognitive therapy is DBT’s emphasis on functional, effective thinking rather than on rationally or empirically based thinking (Linehan, 1993a). If an adolescent thinks, “Nobody wants to date me,” there may be some truth to it—but the thought may lead to dysfunctional behaviors that make it self-fulfilling, such as overeating or assuming postures that convey shame. Cognitive modification may involve helping the client change her thinking to “I haven’t been dating, and many of the things I do contribute to that. I will have to start working on some of these things.”

Jessica’s automatic thought “No one loves me any more” was an example of emotional reasoning (“I feel like no one loves me; therefore it’s true”) and all-or-nothing thinking (“Either everyone loves me or no one loves me”) (Burns, 1989). The therapist helped Jessica recognize that although her parents, boyfriend, and best friend were not actively expressing love in their respective interactions in those moments, they were all known to express love at other times. And even if it were true that her boyfriend did not love her like he used to, did that mean that no one else loved her? The therapist helped Jessica generate some rational responses to these distorted cognitions, such as “Although they’re not expressing it right now, I know they love me because they’ve expressed it at other times,” and “Even though I’m not sure about my boyfriend’s feelings for me right now, I know I am loved by my family.” At the same time, Jessica learned that these thoughts contributed to certain dysfunctional behaviors that she could address. She might be better able to experience loving interactions with the people in her life if she reduced her irritability, was more overtly reinforcing and loving toward them at appropriate times, and was less avoidant when conflicts arose. After spending the remainder of the session on cognitive restructuring, the therapist oriented Jessica to the fact that they would continue to check on her work in this domain.

Typically, one of the most effective and powerful reinforcers for clients with BPD, and for adolescents in general, is the therapeutic relationship. The therapist explicitly uses the relationship as reinforcement for in-session target-relevant adaptive behaviors, by expressing appropriate warmth, attachment, approval, care, concern, and interest. With adolescents, the use of between-session phone contact is often reinforcing, but not always. It is essential to identify reinforcers for each particular client, rather than assuming that something is reinforcing. One way we address this potential problem is by inviting our adolescent clients to “practice-page” us in the first week of treatment. This allows an adolescent to have a brief, benign contact with a therapist, which helps disconfirm the notion that the call will be aversive when a problem arises. Jessica was asked to practice-page her therapist during the following week when she was not in distress:

“Jessica, as you said, your suicide attempt was an impulsive act. We need to help you slow down enough that you can identify your distress, recognize your need for help, and generate alternative solutions. If you have trouble doing that in the beginning, which you may, I want you to page me for coaching. This way we can work together as a team. Therefore, I want you to practice-page me on Tuesday night when you are not in crisis, so that calling becomes more comfortable and automatic.”

Once a client feels attached to the therapist, the therapist’s emotional responses to the client—warm or cool—can become a powerful contingency. At times, these are the only powerful contingencies a therapist has control over. It is important that the therapist respond to client behaviors strategically, remaining well aware of the potential power of his or her response. It is also critical that the therapist assess the potential impact of his or her behaviors. With one client, very slight coolness of affect may be all that is needed to punish unwanted behavior; with another client, it may be necessary to express strong disappointment; with still another, it may be necessary to take a “time out” from a session. The DBT therapist may use the therapeutic relationship as an aversive contingency (i.e., through response cost) in certain specific circumstances: when all other response options have been unsuccessful; when the reinforcing consequences of a high-priority target-relevant maladaptive behavior (such as drug use or promiscuous sexual behavior) are not under the therapist’s control; or when the mal-adaptive behavior interferes with all other adaptive behaviors.

After 6 weeks of treatment, Jessica started calling the therapist frequently and at the same time acting as though the calls were not helpful, not attempting to try the therapist’s suggestions for using skills, and sometimes not talking when the therapist attempted to end a phone call.

THERAPIST: Jessica, I have something I want to talk to you about. You’re pushing my limits on phone calls. When you call me every day, act as though none of my suggestions are helpful, and then either hang up or refuse to get off the phone, I don’t feel like talking to you on the phone [Level 6 validation]. I could make a rule such as “one phone call per week,” but instead of having a rule, let’s say we have a problem that we need to address. I am also wondering if I am missing something else that we should be addressing. What do you think? Doesn’t it seem like you are asking for more phone contact than you used to?

JESSICA: (Looking out window) Do you know that I had a 102-degree temperature yesterday [diverting]?

THERAPIST: What do you think is going on with these phone calls? What is it that you need that you are not getting right now?

JESSICA: (Silent, then:) Fine, I won’t call you.

THERAPIST: I thought that instead of having a rule, we could have a conversation and problem-solve together. Rules give me all of the control. Let’s figure out how to get your behavior under your control and help you get what you need without pushing my limits [highlighting both ends of the dialectic].

In the example above, the therapist explained that Jessica’s behavior was pushing the therapist’s personal limits. The therapist used self-involving self-disclosure (a reciprocal communication strategy) to explain how he felt when Jessica acted that way. He oriented Jessica to the problem, attempted to problem-solve, and used contingency clarification (i.e., if this behavior was not extinguished, the therapist would have to employ consequences, such as “rules” to change the behavior). The fact that a therapist has personal limits needs to be communicated ahead of time, usually during the orientation process.

Clients can apply contingency management techniques to their own lives outside of sessions. Clients are taught to reward themselves for taking small steps in the right direction. For example, one client who had stopped going to classes, and thus stopped doing any school-work, chose to buy herself a new compact disc by her favorite artist after the first week of having gone back to school and done her homework. Another contingency management technique taught to clients is to structure their environment in such a way as not to reinforce their own maladaptive behaviors. For example, one client agreed to have no contact with her boyfriend at all during the hours of multifamily skills training group sessions, whether she attended the group or not. This contingency was effectively implemented so that contact with the boyfriend could not serve as a reinforcer for her not attending group, which it had in the past.

In Jessica’s behavioral chain analysis, it became clear that Jessica’s boyfriend and parents inadvertently reinforced her suicidal behavior by lavishing her with affection and offering her gifts after such incidents rather than before. Changing these reinforcement contingencies for Jessica involved the use of DBT case management strategies—specifically, consultation to the client and environmental intervention. In the role of consultant, Jessica’s therapist encouraged and coached her to speak with her boyfriend and her parents about their inadvertent reinforcement of her suicidal behavior. Jessica had initially requested that the therapist do it for her. The coaching happened in the context of role playing with the client beforehand. If Jessica deemed it too difficult to discuss this issue outside of session, or if her parents were unresponsive to her, the therapist mentioned the possibility of having her speak to her parents in a family session.

The environmental intervention of a family session is typically used only as a last resort in DBT with adults. But, obviously, working with adolescents requires mental health professionals to intervene in the environment more often than with adult clients. If an adolescent is at high risk for suicide, the therapist must contact the client’s relatives, asking them to remove any available means of suicide from the home, and in some circumstances must admit the client to a hospital. Also, at times, the therapist is required for legal and practical reasons to become less of a consultant to the client and more of an advocate. For example, mental health professionals are mandated reporters of child abuse and neglect. Thus, for clients under the age of 18, therapists must call child protective services when there is a suspicion of abuse or neglect, even when an adolescent does not want the call to be made.

When Jessica attempted to discuss the issue of inadvertent reinforcement at home, her parents were distracted and unable to comprehend the important message she was trying to deliver. It then became necessary for her therapist to present the issue to her parents in a family session. With the therapist’s encouragement in session, Jessica acknowledged to them that her suicidal behavior also functioned as a method of escaping her emotional pain (i.e., negative reinforcement) and was effective to that end in the short term. However, she also admitted to feelings of shame that she had to resort to this extreme life-threatening behavior to achieve a sense of relief. These feelings of shame ultimately outweighed the short-term benefit of escape that the suicidal behavior provided.

We discuss general family session procedures in Chapter 9.

Once alternative solutions and change procedures have been identified, the client needs to be motivated to use them. Therefore, the orienting and commitment strategies we have discussed in Chapter 7 are also woven into problem solving as needed. For example, Jessica’s therapist assigned her four major tasks as homework, knowing she would protest: (1) Follow sleep protocol; (2) track automatic thoughts when she was feeling emotional; (3) discuss with her boyfriend and family the positive reinforcement she received from them after self-harming; and (4) practice-page the therapist. This was an example of the door-in-the-face strategy, and the therapist received the reaction he expected: Jessica said, “That’s too much. I can’t do that much homework for therapy when I am behind on my schoolwork!” The therapist replied, “OK, how about choosing the two assignments that you can commit to practicing this week? We’ll work on the others after that.” Jessica experienced this as somewhat of a bargain, and the therapist saw this as an accomplishment by getting her to practice two behavioral assignments instead of the usual one, while simultaneously strengthening her commitment by having her choose which two she was going to practice.

With every possible solution generated there is potential trouble. When the client and therapist have evaluated several possible solutions to a problem, it is imperative that the therapist help the client troubleshoot each solution. That is, the client and therapist must consider potential obstacles to these solutions and figure out how these obstacles can be overcome to ensure that the solution works. Since Jessica chose to practice her sleep hygiene protocol and talk to her boyfriend and parents about their inadvertent reinforcement of self-harm, the therapist asked, “Jessica, what might interfere in your following your sleep protocol? And what might interfere in your discussing this problem with your boyfriend and parents? Let’s take the possible difficulties one at a time.” First, Jessica revealed that she did not have an alarm clock and thus relied on her family members to wake her up each morning. She also anticipated that it might be hard to stay off the Internet at night, since she would often e-mail her friends until the early morning hours. Jessica agreed that she would purchase an alarm clock immediately after the therapy session. In addition, she estimated that she would be able to extricate herself from her computer if she designated a specific time (10:30 P.M.) and had another activity to engage her (i.e., reading a book). Finally, she agreed to call her therapist at midweek if she found herself unable to follow this plan.

Troubleshooting the second solution revealed Jessica’s fear of her parent’s reactions. She expected a critical reaction to her raising the issue of their reinforcement of her suicidal behavior. She and her therapist decided that she would only discuss this issue with her boyfriend during this week, since they had just role-played it during session and she had much less apprehension about discussing this subject with him. Once she had an opportunity to “practice” this discussion with him, and then report back in therapy, Jessica and the therapist could decide how to proceed with her parents.

The important message here for all of us as clinicians is while we encourage, push, and sometimes drag new behavior out of our multiproblem adolescents, we often get even more mileage when we can successfully troubleshoot solutions and remember the principle of shaping. New DBT therapists rarely devote enough time to troubleshooting the solutions. As a result, they often have poorer compliance with their assignments, and thus worse outcomes.

Similar to out-of-session dysfunctional behaviors, the therapist must attend to in-session dysfunctional behaviors. There are several payoffs for treating in-session behaviors. First, learning takes place “in the fire,” where it is most relevant and with the therapist present. In addition, the therapist can explicitly link in-session learning with relevant natural contexts. For example, when Jessica became ashamed while discussing her self-harm during the behavioral analysis, she began to shut down and tried to avoid discussing the problem behavior. The therapist was able to target this emotional response immediately, point out the adverse consequences of avoiding, and establish commitment to begin exposure to this emotion, which would then allow them to target the feelings of abandonment and sadness that preceded the self-harm.

Unfortunately, therapists often fail to address in-session dysfunctional behaviors because of several factors: failure to recognize behaviors as dysfunctional; removal of cues that provoke the in-session dysfunctional response (e.g., stopping the discussion of a topic that makes the adolescent angry); the therapist’s own dysfunctional cognitions (“If I bring this topic up with my client, she’ll get angry and storm out, so I better not”); the therapist’s own skills deficits (recognizing a problem behavior but not knowing how to address it, such as by orienting and then conducting exposure to shame); the therapist’s own emotional avoidance (e.g., the therapist has difficulty tolerating sadness or anger, and consequently avoids discussing topics with the client that may elicit those emotions); and contingencies operating on the therapist (e.g., the therapist receives smiles and laughs from the client when discussing nontarget behaviors, and receives verbal attacks and noncollaboration when discussing in-session dysfunctional behaviors).

Some important guidelines for treating an in-session dysfunctional behavior include staying dialectical, identifying and naming the problem behavior, trying not to remove cues, regulating one’s own emotions, linking in-session behaviors with out-of-session behaviors, and demanding and getting new behavior in session.

Several sessions into Jessica’s treatment, whenever discussion of therapy-interfering behaviors became necessary, she became increasingly sad, noncollaborative, and passive by stating, “I don’t know, I don’t care.” The therapist made use of a DBT protocol to target this in-session dysfunctional behavior (Linehan, 1995). Table 8.4 lists the essential steps for targeting such behaviors.

THERAPIST: Jessica, I notice a problem that we have here: Every time we discuss a therapy-interfering behavior, you get sad, passive, and noncollaborative [observing]. I realize that this problem comes up in your other relationships, too. When you feel like someone is critical of you or pointing out a problem in the relationship, you get sad and withdrawn. In here, when you get passive and withdraw, I feel like we’re not working as a team; I can tell you are upset [Level 3 validation]; and I feel frustrated [self-involving self-disclosure, Level 6 validation]. It’s like you feel and act “blah.” Do you know what I am talking about?

JESSICA: Yes.…I never thought of it that way before, but you’re right (sigh).

THERAPIST: This “blah” approach to solving interpersonal issues is your mortal enemy. You avoid solving the problem, and you don’t learn how to work through issues with other people—which often lead to a variety of problems, including suicidal behavior. If you have the urge to withdraw when you’re feeling sad, you have to fight it as hard as you can. What skills can you use when this happens [eliciting a skillful response or opposite action]?

JESSICA: (Hesitates) I don’t know… and I really don’t know; I am not just saying that.

THERAPIST: Listen, when this “blah” shows up, first you have to be mindful. That is, you need to observe it, describe it, and not judge it. Next you have to do your best to be effective and participate in the session as best you can. That may involve telling me what you’re feeling in words…or it may be noticing the blah feeling, letting it wash over you, and then participating in the session by the acting opposite of your current emotion without further discussion of the blah [instructing].

TABLE 8.4. Essential Steps for Targeting In-Session Dysfunctional Behaviors

|

When clients are in distress, it is not always immediately apparent to them why they should use a specific skill in a specific situation and/or how they can use it effectively. To make use of a metaphor, it can be like telling a person in a burning, smoke-filled kitchen to run through the burning living room to get outside, since that is the only way to get to the door. You may see it’s the only way out, but the person inside might not. The therapist must make it vivid and impress upon the client as highlighted above how treatment tasks and rationales clearly relate to the client’s goals, especially when the client is in intense emotional pain that the therapist and client are unable to alleviate quickly. The aforementioned metaphor is one example of a dialectical strategy used with clients in distress in order to facilitate movement (behaviorally, emotionally, and/or cognitively) when they are “stuck.”

THERAPIST: You have to try this new approach to save your life. Seriously, not only does it slow us down in here, but it dramatically affects your relationships outside of here. I think it also connects to your life-threatening behavior [orienting]. Are you willing to use your mindfulness skills (and possibly act opposite) [commitment]?

JESSICA: Yes, I’ll try it, but it’s going to be hard.

THERAPIST: Of course it will be difficult [Levels 4 and 5 validation]. If it were easy, you’d be doing it already [irreverent communication].…OK, let’s practice it. Imagine that we start discussing your lateness to session, and that the “blah” feeling comes over you again. What do you do [practice]?

JESSICA: I have to observe and describe my blahness.

THERAPIST: Good [positive reinforcement]. What else?

JESSICA: I can say, “Dr. M., I am feeling sad and I am starting to feel blah.”

THERAPIST: Perfect. Then I might say, “Jessica, try to participate fully and nonjudgmentally by throwing yourself back into the problem-solving discussion about your lateness. I am not criticizing you when we discuss this…I just want to figure out what is interfering in your getting here on time and come up with a solution, so that we have more time to discuss the other things you put on the agenda.”

JESSICA: OK. I know I was late because my boyfriend wanted to fool around after school and I lost track of time.

THERAPIST: That makes sense [Level 5 validation]. And good work, Jessica, throwing yourself back into the discussion of therapy-interfering behavior!…Now what can we count on to go wrong and interfere with your using these skills next time it comes up in session? How are we going to handle that?

Dialectical strategies permeate the entire treatment and are used heavily in individual therapy. They emphasize the tensions elicited by contradictory emotions, cognitions, and behavior patterns, both within the individual and between the individual and the environment. Within the therapeutic interaction, the therapist consciously monitors the balance of change and acceptance, flexibility and stability, challenging and nurturing, and other dialectics, in order to maintain a collaborative working relationship in the moment-to-moment interactions with the patient. The therapist also highlights for the patient the dialectical contradictions of the patient’s own behavior and thinking by opposing any term or proposition with its opposite or an alternative. The point is that either extreme of a dialectic is an unhelpful place to be, so the patient is helped to find the middle way by moving from “either-or” to “both-and.” For example, when discussing with Jessica her maladaptive telephone calling behavior that was pushing his limits, the therapist said, “Let’s figure out how to get your behavior under your control and help you get what you need without pushing my limits.”

As mentioned earlier, many suicidal multiproblem teens experience intense emotions during their therapy sessions. Some clients are worried about “opening up” because they are concerned that they will have insufficient time to get themselves “back together” if they do. Thus one of the most important aspects of ending a session is allotting enough time to wrap up. The client needs to know that the therapist is considerate and sensitive to the issue of intense emotion; this increases the likelihood that the adolescent will “open up.” The therapist does not want the client to walk out of the office in an unadulterated state of emotion mind (e.g., panic, sadness, hopelessness) and resort to self-harm. Since each client is different and may require different amounts of time to wind down, each client and therapist dyad should discuss this issue together as it becomes apparent, so that the appropriate amount of time is left for closure. Closure time may include (1) agreeing on (and troubleshooting) homework for the upcoming week; (2) summarizing the session, including (when appropriate) cheerleading, soothing, and reassuring the client; (3) troubleshooting the client’s emotional reactions; (4) giving the client a tape of the session; and (5) engaging in an ending ritual. For example, many teens find engaging in a mindfulness exercise helpful in reorienting themselves at the end of an emotionally dysregulating session.

During the session, the client and therapist have usually identified certain problem areas the client needs to work on during the upcoming week. At the end of the session, the therapist and client collaboratively review what has been discussed and determine whether any of these areas should serve as homework assignments during the upcoming week. Once the assignment is identified, the therapist should troubleshoot any potential difficulties that may arise for the client when he or she tries to use these skills later in the week. As mentioned earlier, Jessica agreed to practice her sleep hygiene and discuss the issue of inadvertent reinforcement of her self-harming behavior with her boyfriend. Before she went off to use her interpersonal DEAR MAN skills with her boyfriend, Jessica and her therapist considered all possible outcomes. These included which emotions were likely to result from the different outcomes, and which distress tolerance skills could be employed if the outcome was less than desirable. In addition, they decided that Jessica would purchase an alarm clock to help her with her sleep protocol.

It is sometimes useful to review the major points addressed in the session, especially when numerous issues have been discussed in a session. When this has been done, the therapist should give a one- or two-sentence summary in an upbeat manner, which highlights any new insights gained during the session as well as any accomplishments or progress made. For example, “Jessica, you did a wonderful job resisting the urge to use drugs this past week by using your ACCEPTS skill to distract yourself. Let’s keep that up and recommit to doing the same with your self-harm.” Most session time is spent on analyzing dysfunctional behaviors, and so it is important at the end to validate the client’s experience of the difficulty of changing these behaviors. At the same time, the therapist needs to cheerlead and encourage the client onward: “You did a great job role-playing the conversation you want to have with your boyfriend. It may be difficult to initiate it, but I think when you get rolling, you’ll do a fine job.”

Given that most adolescent clients have tremendous difficulty reaching out for help, it is important for the therapist to reassure the client that the therapist is available to call for coaching before a crisis is reached. With Jessica, the therapist reassured her by encouraging her to call for coaching if she wanted it before she spoke to her boyfriend. Letting clients know that their therapists are available to them outside of session time is extremely valuable in its capacity to soothe and reassure them that they are not alone and that help is just one phone call away. Some clients have told us that being told they could call any time had an immediate impact on lessening their suicidal ideation.

It is a good rule of thumb for therapists to anticipate that emotional reactions will linger after sessions. Even when a client reports feeling “OK” at the end of a session, it is wise for the therapist to anticipate reactions that may result, troubleshoot those reactions, and determine what distress tolerance and emotion regulation skills the client can use to avoid engaging in maladaptive behavior.

Some clients who need or want an audiotape of a session are more than welcome to take the tape home with them and listen to it during the week. This is especially useful for many of our clients, who become profoundly emotionally dysregulated during sessions and have difficulty recalling anything that happened afterward. Also, for clients who want to have more contact with the therapist, listening to the tape can sometimes achieve that goal.

For some clients and therapists, developing an ending ritual can make leaving the session easier. With one male client, the male therapist engaged in a particular “street” handshake that conveyed a level of intimacy. For other therapists and clients, a goodbye hug might be used. For some, a mindfulness exercise is employed. At a minimum, the therapist should walk the client to the door and convey the expectation that they will see each other again soon.

The individual therapist is responsible for the treatment mode of telephone consultation with the adolescent on an as-needed basis. As described in Chapter 4, telephone calls with the therapist between individual sessions enable the therapist to provide skills coaching and emergency crisis intervention, enable the client to report good news, and help both to repair ruptures in the therapeutic relationship. Our emphasis in this section of the chapter is on the first two of these functions (skills coaching and emergency crisis intervention) in the context of self-injurious behavior.

In keeping with the principle of not reinforcing suicidal behavior, an adolescent client should be emphatically encouraged to contact the therapist prior to any such behavior. Adult clients in DBT are not allowed to call their therapists for 24 hours after a self-harm act (unless the injuries are life-threatening). This rule is not appropriate for adolescents, for several reasons. Since adolescents are minors, it is unwise to entrust them with handling the aftereffects of suicidal behavior. They may not be aware of, or have access to, resources for help (e.g., emergency phone numbers). They are less able than adults to determine the level of lethality of their behavior, and their parents may not know what has occurred. Therapists should, however, explain to adolescents the futility of contacting them afterward and use commitment strategies from the outset of treatment toward this end. Here is how Jessica’s therapist oriented her to the guidelines for this type of phone call:

“Jessica, when you have an urge to harm or kill yourself, I want you first to attempt to use skills you are learning in group. However, if those do not help, I want you to page me for coaching before you harm yourself. It does no good to call me afterward, since you already decided how to solve your problem in that moment, and there is nothing I can do at that point, right?” [Jessica: “I guess so.”] “You see, if you recognize your distress early enough and call me before it gets too intense, we can work together at identifying some alternatives besides self-harm or suicide.”

In this example, the therapist did not formally employ the 24-hour rule; rather, he strongly discouraged calling afterwards by pointing out its ineffectiveness. And although we recommend that therapists should not employ a policy against contact following a suicide attempt or NSIB by adolescents, they should make every effort not to reinforce such behavior if clients do contact them afterward.

Earlier in this chapter, we have shown how a primary therapist handles an adolescent who reports during a therapy session that he or she has already engaged in suicide attempts or NSIB. On the phone, however, the main goals are more narrowly defined: to assess the medical lethality of the act, to ensure that the adolescent receives any needed medical attention, and (when possible) to inform a family member, while trying hard not to reinforce the self-injurious behavior. Issues of confidentiality with adolescents regarding suicidal behavior are discussed in Chapter 9.

One week after Jessica’s therapist instructed her to call before engaging in any self-injurious behavior, Jessica called her therapist at 1 A.M. The call followed an episode of self-cutting, and the conversation went as follows:

THERAPIST: Hello?

JESSICA: Hi, Dr. M., it’s me Jessica.

THERAPIST: Hi Jessica, what’s going on?

JESSICA: Well, Jason [boyfriend] really pissed me off because we planned to spend the weekend together, and then he came over, we had sex, and then he told me he was going to hang out with his friends tomorrow….

THERAPIST: So, Jessica, what are you calling about right now?

JESSICA: Well, I cut myself a few minutes ago.

THERAPIST: Oh, I see (withholding warmth). So where did you cut yourself, and with what?

JESSICA: I cut my ankle with a pin.

THERAPIST: Are you bleeding?

JESSICA: Yeah, but not that bad…it’s basically stopped.

THERAPIST: Well, I can tell you had a fight with Jason, which made you upset. But since you already cut yourself, there is nothing I can do at the moment. Are you having more urges to cut now?

JESSICA: No…I am just angry.