In the first part of this chapter, we look at how the responsibility for meeting treatment functions and Stage 1 behavioral targets is spread among various treatment modes. As we will show, the hierarchy of Stage 1 targets shifts, depending on each mode’s function. In the latter part of the chapter, we address issues involved in setting up a DBT program for adolescents, including factors to consider both within and across treatment modes.

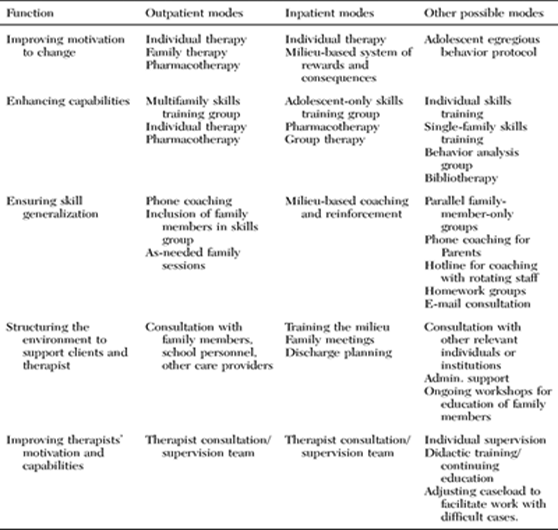

As outlined in the preceding chapter, the primary targets of DBT Stage 1 are decreasing life-threatening behaviors, decreasing therapy-interfering behaviors, decreasing quality-of-life interfering behaviors, and increasing behavioral skills. These specific treatment targets can only be met if the therapy program as a whole serves the following five functions: to motivate clients by reducing emotions, beliefs, and reinforcers conducive to dysfunctional behaviors; to increase clients’ capabilities and skills; to ensure that clients’ new behaviors generalize to the natural environment; to structure the environment to support both clients and therapists; and to improve therapists’ motivation and capability for conducting effective therapy. As we have noted in Chapter 3, it is not the mode itself that is critical, but its ability to address a particular function. An overview of each function, and examples of potential modes of treatment to address each function, are presented in Table 4.1. The arrangement of functions and modes in a DBT program determines who does what and when. In what follows, we discuss potential modes in adolescent DBT that address each function.

Individual therapy sessions constitute the primary setting in which adolescents learn to apply skills taught in the skills training group to their own lives. Thus individual therapists address not only skill capabilities, but also motivational and environmental factors that inhibit effective coping styles or reinforce dysfunctional coping behaviors. The individual therapist is the primary therapist and is responsible for (1) assessing all problem behaviors and skill deficits, all relevant antecedents and consequences of targeted behaviors, and motivational problems; (2) problem solving for these problem behaviors; and (3) organizing other modes to address problems in each area. Individual outpatient therapy sessions are usually scheduled once weekly for 50-60 minutes each, although biweekly sessions may be held during crisis periods or at the beginning of therapy.

TABLE 4.1 Functions of Comprehensive Treatment for Adolescents, and Examples of Potential Modes to Address Them

The priorities of specific targets within individual therapy are the same as the overall Stage 1 priorities of DBT discussed above. Therapeutic focus within individual therapy sessions is determined by the highest-priority treatment target relevant at the moment. This ordering does not change over the course of therapy; however, the relevance of a target does change. Relevance is determined either by a client’s most recent day-to-day behavior (since the last session) or by current behavior during the therapy session; problems not currently in evidence are not considered relevant. If satisfactory progress on one target goal has been achieved, has never been a problem, or is currently not evident, the therapist shifts attention to the immediately following treatment target.

The consequence of this priority allocation is that when high-risk suicidal behaviors or NSIB, therapy-interfering behaviors, or serious quality-of-life-interfering behaviors are occurring, at least part of the session agenda must be devoted to these topics. If these behaviors are not occurring at the moment, then the topics to be discussed are set by the client. The therapeutic focus (within any topic area discussed) depends on the hierarchy of primary targets, the skills targeted for improvement, and any secondary targets. For example, if suicidal behavior has occurred during the previous week, attention to it would take precedence over attention to therapy-interfering behavior. In turn, focusing on therapy-interfering behaviors would take precedence over working on quality-of-life-interfering behaviors. Although it is ordinarily possible to work on more than one target (including those generated by the client) in a given session, higher-priority targets always take precedence.

Determining the relevance of targeted behaviors is assisted by the use of diary cards. These cards are filled out and brought to weekly sessions. Failure to complete or bring in a card is considered a therapy-interfering behavior. Diary cards record daily instances of suicidal acts or NSIB, suicidal ideation, urges to commit suicide or NSIB, “misery,” use of substances (licit and illicit), and use of behavioral skills. Other targeted behaviors (e.g., bulimic episodes, daily productive activities, flashbacks, etc.) may also be recorded on the blank area of the card. The therapist doing DBT must develop the pattern of routinely reviewing the card at the beginning of each session. If the card indicates that a suicidal act or an NSIB has occurred, it is noted and discussed. If high suicidal ideation is recorded, it is assessed to determine whether the client is at risk for suicide. If a pattern of substance abuse or dependence appears, it is treated as a quality-of-life-interfering behavior.

Work on targeted behaviors involves a coordinated array of treatment strategies, as described in Chapter 3 (see also Figure 3.1). Essentially, each session is a balance between change and acceptance strategies. More specifically, following behavioral analysis, this is a balance between structured as well as unstructured problem solving (including simple interpretive activities by the therapist) and unstructured validation. The amount of therapist time allocated to each (problem solving or validating) depends on the urgency of the behaviors needing change or problems to be solved on the one hand, and the urgency of the client’s needs for validation, understanding, and acceptance without any intimation that change is needed on the other.

Some settings with a high patient-to-staff ratio conduct individual behavioral analysis and problem solving in a group therapy mode. Other settings—ones that have limited resources or time, or that are just beginning a DBT program for the first time and wish to start gradually—might forgo this mode entirely and provide only skills training. However, research indicates that training in DBT skills with no DBT individual therapy may be no more effective than treatment as usual (Linehan, 1993a). So if individual DBT therapy is not possible, we recommend that some provision for coaching and generalization be made. For example, skills training would be enhanced by the availability of telephone coaching (outpatient settings) or reinforcement by the milieu (inpatient/residential settings).

Increasing behavioral skills is a Stage 1 primary treatment target. However, skills acquisition within individual psychotherapy is very difficult because of the need for crisis intervention and attention to other issues. Thus a separate component of treatment directly targets the acquisition of behavioral skills. Skills training is typically addressed in a group format. If it is not feasible to get a group started in particular a setting, teaching skills individually might be considered; this can be done either by the primary therapist or by another therapist at another time. If the primary (individual) therapist teaches skills, we recommend actually scheduling a separate session each week to address only skills. If getting to the clinic is an issue for a client, then double sessions might be scheduled (in which the first half focuses on skills, a break occurs, and then the second half focuses on individual behavioral analysis and problem solving). We recommend a clear break between modes; trying to shore up capabilities while handling ongoing crises is like trying to build a shelter in the midst of a storm. One cannot address crises without skills; one cannot learn skills while responding to crises. Thus a clear break between the two modes allows for a separate and distinct focus on each important goal without interference.

As can be seen in Table 4.2, standard DBT teaches a comprehensive set of skills that are grouped within four skills modules: Mindfulness Skills, Emotion Regulation Skills, Interpersonal Effectiveness Skills, and Distress Tolerance Skills. A fifth module, Walking the Middle Path Skills, is adolescent-specific and can be taught as well. (We describe this module in more detail later in this chapter.) Because there is a great deal of material to cover, skills training in DBT follows a psychoeducational format. In contrast to individual therapy, where the agenda is determined primarily by the problem to be solved, in skills training the agenda is set by the skill to be taught. Thus the fundamental priorities here are skill acquisition and strengthening. Although stopping client behaviors that seriously threaten life (e.g., potential suicide or homicide) or continuation of therapy (e.g., not coming to skills training sessions, verbally attacking others in group sessions) is still a first priority, less severe therapy-interfering behaviors (e.g., refusing to talk in a group setting, restless pacing in the middle of sessions, attacking the therapist and/or the therapy) are not given the attention in skills training that they are given in the individual psychotherapy mode. If such behaviors were a primary focus, there would never be time for teaching behavioral skills. Generally, therapy-interfering behaviors are put on an extinction schedule while the client is “dragged” through skills training and simultaneously soothed. In DBT, all Stage 1 skills training clients are required to be in concurrent individual psychotherapy. Throughout, each client is urged to address other problematic behaviors with his or her primary therapist; if a serious risk of suicide develops, the skills training therapist (if different from the primary therapist) refers the problem to the primary therapist.

TABLE 4.2. Overview of Specific DBT Skills by Module

| Module: Core Mindfulness Skills |

“Wise mind” (state of mind) “What skills” (observe, describe, participate) “How skills” (don’t judge, focus on one thing mindfully, do what works) |

| Module: Emotion Regulation Skills |

Observing and describing emotions Reducing vulnerability to emotion mind: PLEASE MASTER (treat PhysicaL illness, balance Eating, avoid mood-Altering drugs, balance Sleep, get Exercise; build MASTERy) Increasing positive emotions Mindfulness of current emotion Acting opposite to current emotion |

| Module: Interpersonal Effectiveness Skills |

DEAR MAN (Describe, Express, Assert, Reinforce; stay Mindful, Appear confident, Negotiate) GIVE (be Gentle, act Interested, Validate, use an Easy manner) FAST (be Fair, noApologies, Stick to values, be Truthful) |

| Module: Distress Tolerance Skills |

Distracting with “Wise mind ACCEPTS” (Activities, Contributing, Comparisons, Emotions, Pushing away, Thoughts, Sensations) Self-soothing the five senses (vision, hearing, smell, taste, touch) Pros and cons IMPROVE the moment (Imagery, Meaning, Prayer, Relaxation, One thing in the moment, Vacation, Encouragement) Radical acceptance Turning the mind Willingness |

| Module: Walking the Middle Path Skills |

Employing behavioral principles: Self and other Validation: Self and other Thinking dialectically Acting dialectically |

In some settings, therapists, while not doing DBT as the primary treatment approach, nevertheless reserve a portion of each session to cover DBT skills from the skills training manual (Linehan, 1993b). This is often because a client or therapist has learned of the treatment and wishes to incorporate aspects of it into the therapy. In such cases, we recommend that the therapist coach the client and consider ways to enhance generalization, since these factors are essential in the client’s truly learning and applying the skills.

Finally, many DBT programs offer some type of maintenance or graduate group to clients who complete Stage 1 of treatment. Such groups are designed to continue addressing the treatment functions of improving capabilities, improving motivation, and promoting generalization of skills. Often such graduate groups are structured in a less intensive manner (in terms of both the adolescents’ participation and the resources of the program). These groups are discussed later in this chapter and in Chapter 11.

Telephone calls between sessions are an integral part of outpatient DBT. When DBT is conducted in other settings, such as inpatient units, other extratherapeutic contact can be arranged. Phone calls have several important purposes: (1) to provide coaching in skills and promote skill generalization; (2) to provide emergency crisis intervention; (3) to break the link between suicidal behaviors and therapist attention by inviting contact for “good news”; and (4) to provide a context for repairing the therapeutic relationship without requiring the client to wait until the next session. When a phone call is made to seek help, the focus of the phone session varies, depending on the complexity and severity of the problem to be solved and the amount of time the therapist is willing to spend on the phone. In a situation where it is reasonably easy to determine what the client should do, the focus is on helping the client use behavioral skills (rather than dysfunctional behaviors) to address the problem. With a complex problem or with a problem too severe for the client to resolve soon, the focus is on ameliorating and tolerating distress and inhibiting dysfunctional problem-solving behaviors until the next therapy session. In the latter case, resolving the problem that set off the crisis is not the target of the phone session.

With the exception of taking necessary steps to protect a client’s life when suicide is threatened, all calls for help are handled as much alike as possible. This is done to break the association between suicidal behaviors and increased phone contact. To do this, a therapist can do one of two things: refuse to accept any calls, including suicide crisis calls, or insist that a client who calls during such crises also call during other crises and problem situations. Because experts on suicidal behaviors uniformly say that therapist availability is necessary with suicidal clients (see Linehan, 1993a), DBT chooses the latter course; it encourages (and at times insists) on calls during nonsuicidal crisis periods, as well as calls to share good news. In DBT, calling the therapist too infrequently, as well as too frequently, would be considered therapy-interfering behavior.

The final priority for phone calls to individual therapists is relationship repair. Clients with BPD or borderline features often experience delayed emotional reactions to interactions that have occurred during therapy sessions. From a DBT perspective, it is not reasonable to require clients to wait up to a whole week before dealing with these emotions, and it is appropriate for clients to call for a brief “heart-to-heart.” In these situations, the role of the therapist is to soothe and reassure. In-depth analyses should wait until the next session.

In milieu settings, the function of ensuring skill generalization will need to occur through other modes, such as coaching from nursing staff and other members of the milieu, homework groups, or other means. Chapter 8 provides additional discussion on the use of telephone consultation.

In addition to telephone calls, individual therapy helps with the generalization of skills, as the therapist works with the adolescent during behavioral analyses to understand where capability deficits led to problem behaviors and to apply specific skills to those situations. Homework assignments assigned by the individual (as well as group) therapist also promote generalization, by ensuring that the adolescent takes what is learned and applies it in real-life contexts. Individual sessions can also be audiotaped, and the adolescent can listen to the tapes between sessions to further promote generalization. Finally, family therapy sessions (as well as family participation in group) also contribute to skills generalization by providing the adolescent with skills coaches at home, as well as in vivo opportunities to practice in therapeutic contexts.

One of the essential components of DBT is attention to contingencies throughout the entire treatment program. The aim is to be sure that all programmatic rules and all program staff members reinforce skillful rather than maladaptive behaviors. This is especially important with respect to suicidal behaviors. The premise is that if clients can only get help that they want or need by getting more suicidal or engaging in other maladaptive behaviors, then it is doubtful that the treatment as a whole will be effective.

Unlike most adults, however, adolescents are usually still in the original invalidating environment in which they learned dysfunctional patterns. Therefore, to be effective, DBT with adolescents needs to address any invalidating behaviors between family members. It does so by intervening with family members in three different ways: including family members in skills training groups, offering telephone consultation for family members on implementing skills, and integrating family members as needed into individual therapy sessions.

In addition, structuring the environment can be achieved through contact with providers of ancillary treatments, such as psychiatrists or school counselors. Ideally, providers of these treatments will in some way be linked with the DBT treatment team or be familiar with principles of DBT. An example would be a psychiatrist who provides pharmacotherapy at the same clinic that houses the treatment, or, better yet, who is actually a member of the treatment team. In the program at Montefiore Medical Center, we regularly include psychiatrists as part of the consultation team. Thus clients in our DBT program who require medication see one of the team psychiatrists. When it is not possible to include an ancillary treatment provider as part of the DBT team, maintaining contact between the team and the provider, while offering some education and orientation to DBT strategies, is the preferable strategy. For example, we coach the client on how to present DBT to the ancillary provider, including reviewing the skills notebook, assumptions, and rules. For teenagers, ancillary treatment modes often include treatments administered through the school. In residential and day treatment facilities, schooling might be integrated into the treatment; in this case, there should be close contact and cooperation between the treatment and the educational staff. In outpatient settings, therapists deciding to engage school personnel must put in additional effort to arrange meetings, orient these personnel to DBT, and develop treatment plans. This is easier to do when the treatment staff has a continuing relationship with school professionals through a history of referrals and working together.

DBT assumes that effective treatment of BPD must pay as much attention to a therapist’s behavior and experience in therapy as it does to a client’s. Treating clients with suicidal behaviors and/or borderline characteristics is enormously stressful, and staying within the DBT frame can be tremendously difficult. Thus an integral part of the therapy is the treatment of the therapist. All therapists are required to be in a DBT consultation team. DBT team meetings are held weekly and are attended by therapists currently utilizing DBT with clients. Note that this meeting is distinct from staff meetings, morning rounds, or similar meetings that address issues such as clients’ medication status, discharge planning, unit procedures, and the like. When settings or time constraints require incorporating administrative/client management functions into DBT team meetings, it is helpful to set an agenda and limit the time devoted to the former issues, or cover them only after therapist consultation issues have been addressed. This preserves the goal of the consultation meetings: to allow therapists to discuss their difficulties providing treatment in a nonjudgmental and supportive environment that also helps improve their motivation and capabilities. The role of consultation is to hold each therapist within the therapeutic frame and address problems that arise in the course of treatment delivery. Thus the fundamental target is increasing adherence to DBT principles for each member of the consultation team. The DBT team is viewed as an integral component of DBT; it is considered group therapy for the therapists. Each member is simultaneously a client and a therapist in the group.

The DBT consultation team is an essential and ongoing part of the DBT program. That is, the team does not end after any individual’s completion of treatment. Rather, it continues as clients come and go, serving as a sort of backbone of the entire treatment program. Depending on the setting, of course, team members may come and go as the staff turns over. However, almost any setting will ask a practitioner to commit to the team for at least the duration of his or her involvement with DBT. In training settings (e.g., graduate department clinics, teaching hospitals), student team members (i.e., psychology graduate students, residents, social work interns) often remain team members throughout the duration of their placement.

In our programs, we start each team meeting with a brief mindfulness exercise (e.g., observing thoughts, focusing all of one’s attention on one’s breathing, etc.), led by different therapists on a rotating basis, to forge a break with the previous activities of the day and cue a DBT mindset. These exercises also serve to enhance therapists’ skills in leading mindfulness exercises and coaching mindfulness skills. We then read one of the team agreements (to be described below), review the team notes from the previous week, and set an agenda for the meeting. The agenda is set by the team, and the order in which items are discussed is based on the DBT hierarchy of targets: (1) therapist needs for consultation around suicidal crises or other life-threatening behaviors; (2) therapy-interfering behaviors (including client absences and dropouts, as well as therapist therapy-interfering behaviors); (3) therapist team-interfering behaviors and burnout; (4) severe or escalating quality-of-life-interfering behaviors; (5) good news and therapists’ effective behaviors; (6) summary of the previous week’s skills group and graduate group sessions by group leaders; and (7) administrative issues (e.g., requests to miss the next team meeting or be out of town; new client contacts; changes in skills trainers or group time, format of consultation group, etc.). This agenda spans the first hour of the team meeting. Although the agenda may look impossibly long, ordinarily the time is managed by therapists’ being explicit about where they need help and consultation from the team. At the University of Washington, all therapists are asked to come to each team meeting prepared to state what help they need and the importance of their need for time on a scale from 1 to 3. The other half to full hour of the meeting is devoted to maintaining DBT training, including a review of skills corresponding to those being taught in group that week, skills practice, videotapes, or other new teaching materials/exercises. At some sites the training hour is set at a different time of the week, with therapists from all DBT teams attending.

The in-depth discussions of clients and of therapists’ difficulties in delivering competent DBT center around enhancing the therapists’ ability to deliver treatment effectively. This involves validating the therapists’ reactions while still eliciting effective treatment behaviors. Often the team helps a depleted therapist to regain a nonjudgmental, empathic stance toward a client’s behaviors by pointing out perspectives the therapist may no longer be able to generate. Furthermore, the team can help the therapist get unstuck by coaching issues such as handling difficult communications or planning effective contingency management strategies. Teams also address such issues as burnout and personal difficulties or limits that interfere with treatment. In addition, the consultation meeting is focused on therapist behaviors that interfere with team functioning, such as failure to keep agreements made in team, coming late or leaving early, taking responsibility for one’s own clients but not for other clients, talking too much or too little, annoying habits evident in team, and the differences of opinion or conflicts that inevitably arise between members of the treatment team.

DBT promotes a set of agreements for consultation team members that help facilitate interactions between colleagues within the meetings. The agreements are intended to facilitate maintaining a DBT frame. They help to create a supportive environment for managing client–therapist and therapist–therapist difficulties. These agreements apply equally to consultation groups working with adolescent clients. In addition, we have noticed that most of the agreements contain principles that facilitate work with family members as well, as explicated below.

The group agrees to accept a dialectical philosophy. Essentially, this involves adhering to the notion that there is no absolute truth, and thus searching for a synthesis of polarities when extreme viewpoints arise.

We find that extreme viewpoints often arise when therapists are working with adolescent clients. A polarity that arises is “blaming” a teen versus “blaming” a parent. When strong differences of opinion emerge among the team members, this situation is normalized according to the dialectical world view; that is, truth is neither absolute nor relative, and reality exists in opposing forces. Team members are urged to search for the grain of truth in the opposing perspective and work toward a synthesis. It can be helpful to consider whether one is aligning with one of the extreme behavior patterns described in Chapter 5, such as invalidating the client or pathologizing normal behavior.

The second agreement involves consulting to clients on how to interact effectively with others in their environment, rather than consulting with the environment on interacting effectively with clients. This provides clients with opportunities to practice skillful interactions and avoids the trap of reinforcing clients’ tendencies to elicit help from others while themselves remaining passive (see the discussion of “active passivity” in Chapter 5). The agreement implies that if a client tells the individual therapist that he or she is angry with the skills trainer for saying something upsetting in group, the individual therapist consults to the client on how to interact effectively with the skills trainer, instead of telling the skills trainer how to interact with the client.

With adolescents, in contrast to adults, there is typically a need to do more consulting with the environment. For example, minors cannot be expected to initiate contact with ancillary treatment providers (e.g., consultation with a psychiatrist), be fully responsible for getting themselves to sessions when they rely on transportation from parents, or arrange meetings with school personnel. On the other hand, within these constraints, adolescents can nevertheless be coached on how to communicate effectively and play an appropriate and active role in such situations (such as accurately describing medication side effects to a psychiatrist, asserting to parents the importance of making it to therapy and behaving in a way that facilitates this, or speaking with school staff members in a way that helps them to be taken seriously).

Consistency of therapists is not necessarily expected. Treatment team members not only “agree to disagree” with one another; they are also not necessarily expected to be consistent from client to client or over time with the same client. Clashes or mix-ups are regarded as inevitable and as presenting opportunities for clients and treatment staff alike to practice DBT skills. In work with parents of adolescents, it is useful to extend this principle to parents. Therapists and adolescents alike must understand that it is not realistic to expect parents to be perfectly consistent, due to factors such as mood, stress level, or a teen’s presentation. Thus this agreement helps team members accept variations within other members and within the family members of teens attending treatment.

Therapists agree to observe their own personal limits without judging others. They also agree not to make inferences about team members’ limits that seem narrow (e.g., seeing a therapist as withholding, rigid, or self-centered) or broad (e.g., seeing a therapist as needing to rescue a client or as having boundary problems).

This agreement stems from the observation that therapists working with suicidal, emotionally dysregulated clients tend to attribute violations of their own personal limits to clients’ problems with “boundaries.” This makes little sense, as specific therapists’ limits are idiosyncratic. For example, one therapist may be able to tolerate working with a hostile, argumentative adolescent, but not one who calls several times over each weekend. Another may openly receive weekend phone calls, but may quickly burn out with a belligerent teen. Thus notions of clients’ violating boundaries often pathologize the clients, when in fact “crossed boundaries” often say more about therapists’ sensitivities and standards than about clients’ judgment. Furthermore, part of negotiating an interpersonal relationship involves accepting feedback about the other person’s limits, and, just as importantly, developing some ability to “read” the other’s limits. Thus setting universal rules in treatment (e.g., no more than four phone calls per week) would not only be arbitrary and fail to appease every therapist, but would also hinder this potentially therapeutic aspect of the therapist’s self-disclosure. Thus DBT therapists carefully identify their own personal limits and then clarify these limits to clients, while explicitly taking responsibility for them rather than giving the clients responsibility for them. For example, a therapist might tell a client the following: “When you mimic me, insult me, and frequently compare me (unfavorably) to your last therapist, it makes it hard for me to want to keep working with you. A different therapist might not have a big problem with this, but it just crosses my personal limits.”

The team might step in, however, if it becomes apparent that a therapist has drawn limits that interfere with effective therapy. For example, if an overwhelmed therapist begins to stop accepting phone calls outside of ordinary working hours and an adolescent thus loses an opportunity for skills generalization, the team would seek to understand and validate the therapist’s experience, but would also problem-solve to help the therapist become more available to the client (e.g., delay assignment of additional cases or find some way to reduce the therapist’s workload; coach the therapist in keeping phone calls brief and focused or in otherwise handling them in a way that feels more manageable). On the other hand, the team must truly work toward being nonjudgmental about a therapist’s limits and simply accept them when they are not harmful to the therapist’s clients (even if they are narrower than the limits of other team members). For example, one therapist who was threatened with a knife by a college-age client wanted to cease working with the client altogether. Despite the client’s desire to continue working with this therapist, the team supported the therapist in ceasing contact after ensuring that appropriate care was offered to the client (switching to another therapist plus taking additional steps to protect the new therapist’s safety and ease in working with the client).

In working with parents, it is also helpful to keep in mind the principle of observing limits. Parents can often be so anxious about their child’s welfare that they make unreasonable demands on the therapist. Parents who are overwhelmed with other obligations may want the therapist to be unreasonably available to their child or may make unnecessarily frequent calls for advice or reassurance. Parents who are used to having control in their lives may try to control the process of therapy or make insistent demands that confidentiality be broken. In each case, it is the task of the team to assist the therapist in clarifying and managing his or her own limits with the parents.

All therapists agree to search for nonpejorative, phenomenologically empathic interpretations of a client’s behavior. The agreement is based on the DBT assumptions that patients are doing the best they can and want to improve. For example, when a therapist attends a consultation meeting and reports that his or her client is “a manipulative, insensitive, crazy adolescent who makes me want to quit therapy today,” the other team members try to (1) help the therapist generate nonjudgmental, phenomenologically empathic descriptors of the client’s behavior; and (2) validate the therapist’s sense of feeling overwhelmed, angry, and frustrated. To do so might require a colleague to refer to the biosocial theory of BPD. For example, the client’s childhood history of abuse and chronic invalidation may be helpful in explaining the client’s current emotion dysregulation and interpersonal deficits, which quickly alienate those close to him or her. In DBT, a client’s behavior is not considered manipulative without an assessment of the client’s actual motivation. The fact that the therapist feels manipulated does not mean that manipulation was the client’s intent. Nonpejorative descriptions include reminding therapists that clients are doing the best they can, given their limited skills repertoires; indeed, the limitations of their skills repertoires have gotten them into treatment. Moreover, it is difficult for clients to give up their current coping strategies because they are often reinforced, at least in the short term. This dialectical, empathic, nonpejorative thinking reduces the all-or-none thinking often pervasive among clients with BPD or borderline characteristics, and even among the staff members who treat them.

This stance toward empathy for the client’s experience extends to family members as well. This is often difficult; we have seen numerous therapists on our teams become angry or frustrated with parents for their invalidation, noncompliance, or outright therapy-destroying behavior. However, the best chance of forming an alliance with such parents involves maintaining a phenomenologically empathic view of their experience. Keeping in mind the transactional development of BPD, one can consider the difficulty (often spanning the adolescent’s life) of raising an adolescent who seems overly emotional, demanding, and difficult. This is only exacerbated by the pain, fear, and guilt parents often experience as a result of the teen’s suicidal and otherwise self-destructive behavior. Such behaviors place a great strain on parents, who often feel lost or “at their wits’ end.” When the team takes the time to bolster a therapist’s empathic understanding of such a parent’s experience, progress can often be made.

The group members agree that all therapists are fallible. DBT follows the assumption that therapists will make mistakes, and will even violate the present consultation group agreements. The job of the treatment team will be to balance problem solving aimed toward directing a therapist back into a DBT framework with validation of the wisdom present in the therapist’s actions or position.

Again, it is helpful to apply this principle to clients’ family members as well. Parents will inevitably make mistakes. The team can help a therapist accept this inevitability while problem-solving about how to repair the damage from a mistake or otherwise get a parent back on track toward working effectively with a teen.

DBT is the treatment of a community of clients by a community of therapists. Thus therapists agree that they are in fact the therapeutic community for all clients being seen by team members. That is, each person takes responsibility for working to ensure that each client receives the best treatment possible. Therapists agree to speak out actively, both to recognize effective therapy behaviors and to modify or eliminate ineffective therapy behaviors of team members. The suicide of one therapist’s client is the suicide of a client of all therapists.

There are various ways of dividing up responsibilities for conducting DBT teams. We have found that a team does much better when there is an active team leader who is given primary responsibility for knowing, remembering, and articulating the DBT principles when necessary, and for overseeing the fidelity of the treatment provided. This job should be given to the person on the team with the best training in DBT, or, among equally trained (or untrained) therapists, the person with the best leadership qualities. Most teams rotate responsibility for developing and managing the agenda and for writing the team notes among members on either a weekly or monthly basis. Because the team is an integral part of the therapy itself, it is of course important that team notes be taken and kept in the therapy records. At many clinics, the “observer” task of helping team members stay on track with their agreements also rotates among members. At the University of Washington, the observer has a small “mindfulness bell” and rings it whenever team members make judgmental comments (in content or tone) about themselves, each other, or a client; stay polarized without seeking synthesis; fall out of mindfulness by doing two things at once; or jump in to solve a problem before assessing the problem. An entire meeting rarely goes by without the bell’s ringing at least once. (DBT is not for the faint of heart.) We have found that over time team members almost jump over the observer to ring the bell, often catching themselves with judgmental words or thoughts. The secret, of course, is to ring the bell nonjudgmentally.

Anyone who considers starting a DBT program for adolescents needs to answer questions such as the following: How will the adolescent client population be defined? Who will constitute the treatment team? In what modes will clients be treated? Should any adaptations to standard DBT be made? We next discuss these and other issues to consider in setting up a DBT treatment program for adolescents and their families. For much of the discussion that follows, we draw on our personal experiences in DBT programs with adolescents at Montefiore Medical Center (Miller); Long Island University, C. W. Post Campus (Rathus); and the University of Washington Behavioral Research and Therapy Clinic (Linehan). We have also surveyed numerous adolescent DBT programs around the world to help inform this discussion.

Adolescent DBT programs employ varying inclusion criteria, depending on the treatment setting. For example, some DBT programs for adolescent inpatients use suicidal behavior as an inclusion criterion (Katz et al., 2004). Several residential programs employ some degree of injury directed toward self or others as the primary inclusion criterion (Miller, Rathus, et al., in press). One forensic DBT program included those teens with criminal offenses who also engaged in violence toward self or others (Trupin, Stewart, Beach, & Boesky, 2002). One high school selected “at-risk” teens for a lunchtime 22-week DBT skills training group; these youth were defined as truant, violent, self-injurious, and/or substance-abusing (Sally, Jackson, Carney, Kevelson, & Miller, 2002). Most adolescent outpatient DBT programs include teens with histories of suicidal behavior, NSIB, and current suicidal ideation plus BPD features, since these criteria most closely resemble the inclusion criteria used in Linehan’s original outcome studies with suicidal adults (see Miller, Rathus, et al., in press) Among the adolescent DBT programs we surveyed, the youngest clients were 12 and the oldest were 19 years of age, with a median age of 16 (Miller, Rathus, et al., in press).

Most adolescent DBT programs, regardless of setting, exclude teens who present with psychotic disorders, severe cognitive impairment (i.e., IQ lower than 70), or severe receptive or expressive language problems. For example, actively psychotic or actively manic adolescents are excluded from the Montefiore program’s multifamily skills training group and instead are taught skills individually or with their family members, since their psychotic or manic behaviors may become too disruptive to a group. The differential diagnosis between BPD and a bipolar disorder is sometimes difficult to make in adolescents. Also, for reasons discussed in Chapter 1, many clinicians will make Axis I diagnoses but not Axis II diagnoses in adolescents. In the Montefiore program, all clients referred receive a thorough diagnostic evaluation even if they have recently had one somewhere else. We are particularly careful to reassess clients referred with bipolar disorders to clarify the differential diagnosis, since treatments may vary accordingly.

Teens with moderate to severe learning disabilities and those with borderline IQ scores are often included in DBT treatment programs. Accommodations typically include teaching fewer skills at a slower pace, simplifying the terms used to teach, simplifying the diary card, and possibly having clients repeat the skills training curriculum. The following sections take a closer look at other factors (age, gender, diagnosis, and cultural factors) that need to be considered in setting a program’s inclusion and exclusion criteria.

Although adolescents as a group are generally defined as ranging in age from 12 to 19 (Berk, 2004) and some suggest even older, this is not a homogeneous group. Early adolescence (roughly age 11 or 12 to age 14) is characterized by recent entry into puberty; often by firsttime experimenting with things such as dating and substance use; and by attending middle school or junior high school. Those in middle to late adolescence (roughly ages 14 to 18) are typically attending high school and are sandwiched in between the childhood years and adulthood, often facing increased demands, pressures, and responsibility. For example, they may be working, learning to drive, and entering more serious romantic relationships. The oldest adolescents might be considered to range from roughly age 18 to age 20, 21, or even 25. For example, Arnett (1999) has defined a period from ages 18 to 25 called “emerging adulthood” or “transitional adulthood.” According to Arnett, this stage is primarily a middle- and upper-class phenomenon that occurs prior to early adulthood and reflects a sort of extended adolescence. Emerging adulthood is marked by continued financial dependence (and sometimes continued residence in the parents’ home), continued identity development, continued exploration rather than commitment in terms of relationships and vocation, and possible continued engagement in risky or impulsive behaviors.

Given this diversity among age subgroups, how does one define the population of adolescents in terms of age, and should a program mix these various ages or limit treatment to early, middle, or late adolescence or some combination thereof? Moreover, should practitioners base inclusion decisions solely on age, or also on level of functioning? For example, an 18-year-old living at home, attending high school, and dependent on his or her family of origin seems more adolescent-like than an 18-year-old who is working full-time and living independently with a stable partner. Advantages to limiting treatment to particular age groups within adolescence include increased homogeneity in terms of life issues (which may lead to a greater connection to peers in group settings) and the potential for development of greater specialization in a particular stage of adolescence among staff members (e.g., a setting could have its “early adolescence expert” who runs these groups or takes on many of the individual cases). However, a setting must have either enough of a referral base that it can afford to turn away adolescents outside a specific age range, or enough referrals and staff members to fill and run various groups, each limited to specific ages. Some settings might have several groups running simultaneously and might thus choose to have them divided into two (e.g., 12–15, 16–19) or three (e.g., 11–14, 14–17, 17–20) age groupings. Some settings, such as hospitals, may have institution-wide criteria for ages, in which clients ages 17 and younger are treated in a child/adolescent program and clients ages 18 and above automatically receive services in the adult outpatient, day treatment, or inpatient department. Still other settings without a large enough teen referral base may include adolescents ages 16 and older within adult programs.

Because of staff or referral limitations or other reasons, providers may prefer to run mixed-age programs for adolescents. Advantages include the ability to accept a greater range of clients to fill groups, less need to differentiate between age and level of functioning, and the potential for older participants to serve as mentors and models for younger ones. In our Montefiore program, clients are adolescents ranging in age from 12 to 19 years, mixed together in skills groups. We have found that older clients will often play a sort of “big sibling” role to younger clients, coaching them and imparting advice and wisdom. This is inspirational for younger attendees and a source of pride and motivation for older attendees. One risk is accepting an “outlier” in age for a particular group who then ends up feeling alienated—for example, a 19-year-old in a group of mostly 14- and 15-year-olds. To prevent this, the skills trainer may encourage the older teen to play a special role in the group in order to capitalize on the age discrepancy. Other alternatives are referring an outlier adolescent to another group or conducting skills training individually.

Gender is another factor to consider. Will a program include both girls and boys, and if so, will it place them together in groups? Some residential treatment settings are limited to treating one gender, or else separate the genders into different residences. But most other settings admit both boys and girls. Some advantages of limiting a skills group to a single gender are similar to those of limiting a group to a narrow age range: Doing so allows for greater homogeneity of issues brought into the group and perhaps greater comfort with self-disclosure. Furthermore, it may minimize the degree of disruption or distraction due to sexual interest, flirting, or increased social anxiety due to the presence of the opposite sex. (The issue of sexual interest would obviously remain for homosexual adolescents, regardless of group type.)

In our Montefiore and Long Island University programs, however, we combine males and females for several reasons. First, this practice allows us to treat boys in settings that get a low percentage of male referrals, There might not otherwise be enough male participants to fill a group. In our Montefiore settings, only 15–20% of our DBT referrals are male, resulting in about one male adolescent per group of five to six clients and their families. This is typical, given the much higher rates of BPD diagnoses, suicide attempts, and NSIB in females. Second, the presence of both genders allows for developing skillful opposite-sex friendships, role-playing boyfriend–girlfriend conversations with opposite-sex participants, and gaining insight on issues from the other gender’s perspective. This promotes generalization of skills. In a mixed gender group, it is very important to make it clear to members that both boys and girls will be in the group, even if at some points there are no male members. In our University of Washington program, this communication broke down at one point recently. And when a male was accepted into the group, there were extreme emotional reactions and nearpanic on the part of two members who had been previously raped. Although we did not rescind our decision, several extra individual sessions and much coaching were needed to smooth out the transition. The mixed-gender group is now doing very well, and the lone male is “radically accepted,” in the DBT sense (see Linehan, 1993b).

What will a program’s diagnostic entry criteria be? Will clients be suicidal, and if so, how will “suicidality” be defined? Will clients need to meet full criteria for BPD, exhibit subthreshold BPD features, or simply manifest emotional or behavioral dysregulation? How will these criteria be measured? Will clients with comorbid disorders be included, or will certain comorbid disorders be cause for exclusion? Will clients be combined into mixed diagnostic groups, or will they be assigned to relatively homogeneous groups?

Groups with high diagnostic homogeneity would be hard to come by in this field, since suicidal individuals with borderline features tend to be characterized by multiple problems and multiple comorbidities. However, minimal entry criteria (e.g., meeting full criteria for BPD and displaying evidence of recent suicidal behaviors and NSIB) can result in a relatively homogeneous group with the advantage of close similarity to the original group with whom DBT was validated (Linehan et al., 1991; Linehan, 1993a). This may also allow for similar problems raised in group sessions, and thus possibly a greater feeling of connection to the group. Diagnostically mixed groups, however, may also be beneficial; more evidence is emerging that DBT can be successfully adapted for a range of populations and target behaviors (see Miller & Rathus, 2000). Casting a wider net also has the potential to benefit more people, but certain cautions are warranted in combining diagnostic groups or having varied inclusion criteria. First, individuals with certain diagnoses, though appropriate for DBT, might be better served in a DBT or other program specifically tailored for those diagnoses (e.g., primary diagnoses of eating disorders or substance abuse/dependence). Second, certain diagnostic groups may not be best served in group settings. For example, recent evidence finds that youth with conduct disorder or antisocial features fare worse when treated in group formats, because of the modeling, training, and peer validation of antisocial behaviors that occurs (Dishion, McCord, & Poulin, 1999). Third, if entry criteria become too loose, individuals’ severity levels and treatment targets may differ so drastically from one another that group skills training may lose its focus: What is being treated may become unclear, the biosocial theory underlying the treatment may no longer apply, and the group may disintegrate. We thus recommend at least having an identifiable unifying theme that brings group members together.

Our Montefiore program’s entry criteria are that adolescents must both be suicidal (suicide attempt within past 16 weeks or current suicidal ideation) and exhibit borderline personality features (a full BPD diagnosis, or at least three diagnostic criteria). Exclusion criteria consist of active psychosis, severe learning disabilities, or severe cognitive impairment. In addition to BPD, the primary comorbid diagnoses have included mood, anxiety, eating, substance-related, and disruptive behavior disorders.

Will a program be homogeneous or heterogeneous in terms of SES and ethnicity? In general, we have found that the answer to this question tends to be determined by setting. For example, our Montefiore inner-city population consists of mostly lower-SES adolescents who represent ethnic minority groups (predominantly various Hispanic groups, African American youth, and youth of African descent from the Caribbean). Our suburban population consists of mostly middle- to upper-SES American teens. Thus we have no decision to make about whom to assign to groups. However, one might consider whether cultural factors are disparate enough within a given setting that there would be reason to consider assigning clients to groups on this basis. For example, one consideration might be the primary language spoken by the family; some settings have implemented skills groups taught in Spanish to allow family members’ participation when little or no English is spoken. On the other hand, definitions of culture vary widely (see the discussion of culture in Rathus & Feindler, 2004), and culturally diverse groups have the potential to enhance members’ experience.

The treatment team consists of everyone involved with the DBT program across modes—that is, skills trainers, individual therapists, and providers of additional modes within a particular setting (such as nurses in a milieu setting). At a bare minimum, it should consist of at least two mental health professionals trained in DBT and, ideally, experienced in working with adolescents. Having at least one other colleague with whom to discuss one’s own difficulties in providing DBT serves the essential DBT function of enhancing therapist capabilities and motivation, as described earlier in this chapter. And having at least a third DBT therapist can help the team achieve a synthesis when the other two are stuck highlighting opposite poles of a particular dialectic.

The ideal treatment team will depend on the nature of the particular setting, but there are some common elements. First, the more previous DBT training that team members have, the easier DBT is to implement. At a minimum, the team leader should be intensively trained in DBT. Second, experience in working with adolescents is helpful for team members because of the many developmental issues that make adolescents a unique population to work with. Third, family therapy experience is helpful. Many teen programs will include family members. Practitioners must be comfortable working with multiple family members at once. Even when family members are not included in the skills training, they will probably be involved in some way with treatment and have contact with the treatment providers, since their teens are minors. Team members experienced in group work can also make helpful contributions as group skills leaders themselves or as consultants to the skills trainers. In essence, the more experience the team members have in the related aspects of treatment, the better, since the treatment is complex and the populations treated are challenging.

If providers in a setting are inexperienced in DBT, we recommend a structured reading group for self-teaching, plus attendance at available trainings, workshops, and conferences. In-house training can be conducted by team members with expertise in the treatment, and therapist consultation meetings include didactic portions. We have held team meetings in which didactics are taught on a rotating basis; each team member does readings on a skill, strategy, or principle on his or her week to teach, and then runs the didactic portion of that week’s team meeting, teaching peers. We also recommend ongoing individual supervision by a well-trained and experienced therapist or even by outside consultants, in addition to therapist consultation team meetings, for novice DBT therapists. The bottom line is that all participating therapists agree to provide DBT and adhere to the DBT team agreements.

Depending on the setting, the disciplines of team members will vary. Some teams may be multidisciplinary, and others may be limited to one or two disciplines. In our inner-city Montefiore Medical Center setting, our treatment teams have included psychologists, psychologists in training, psychiatrists, and social workers. Representatives of other disciplines can participate as well, such as nurses, caseworkers, or mental health aides. Members of multiple disciplines can be trained to deliver this treatment, and multidisciplinary teams offer various areas of expertise in consulting on each case. For example, when possible, it is helpful to have a nurse practitioner or physician on the team to handle medication issues, rather than having a client’s pharmacotherapy handled by an outside party who is unfamiliar with DBT. In inpatient DBT settings, it is common to have direct care staff members as part of the treatment team—serving as primary therapists or skills coaches, or playing other roles. In our suburban Long Island University psychology training clinic setting, the team initially consisted of one intensively trained psychologist (Rathus) and several graduate students in clinical psychology. Such single-discipline teams are possible and allow for training of new therapists. However, such a team composition (one leader and many trainees) poses a risk of burning out the team leader. The leader in such a situation is advised either to seek outside peer consultation or to require a minimal 2-year commitment from students. That way, once trainees acquire a certain level of experience, they are more skilled and can play more of a senior role on the team (see also Chapter 12).

Whenever possible, we recommend delivering the “gold standard” comprehensive treatment as outlined in Chapter 3 and as originally developed and researched with documented efficacy (Linehan et al., 1991; Linehan, 1993a). We define “comprehensive treatment” as achieving all five of the functions discussed earlier in this chapter (i.e., increasing motivation, enhancing capabilities, generalizing skills, structuring the environment, and enhancing therapists’ capabilities). In a traditional DBT outpatient program, motivational issues are addressed in individual therapy; capabilities are primarily enhanced via a skills training group; skills generalization is achieved by having the client call his or her primary therapist for coaching when the client is in distress; structuring the environment is often achieved through family sessions and/or contacts with the school or other agencies; therapists’ capabilities are enhanced by participation in the therapist consultation meetings and continuing education. (See Table 4.1 on the functions of comprehensive treatment for adolescents.)

As described earlier (and also outlined in Table 4.1), different modalities can be effectively used to achieve these functions, depending on the treatment setting. For example, inpatient and residential units often utilize milieu therapists instead of primary therapists to achieve skills generalization, since the clients can receive in vivo coaching on the unit as soon as they become distressed. Sometimes a setting is unable to identify enough clients who meet criteria to form a skills training group, so they choose to provide individual (or family) skills training in order to address the function of enhancing the client’s capabilities. These adjustments are typically indicated for various settings, and these programs still maintain the five functions and thus the overall comprehensiveness of the DBT model.

What does it mean if an adolescent DBT program does not want to, or is unable to, deliver all five functions? First, providers have to admit to themselves and to clients and families that they are not delivering DBT as it was originally developed and studied. Second, it may be perfectly acceptable to start out on a smaller scale! Furthermore, it remains an empirical question as to which functions are required to achieve treatment efficacy, so we recommend testing the effectiveness of particular interventions in particular settings. We have encountered several situations in which programs, for various reasons, do not deliver the comprehensive treatment. We describe a few examples below.

One common obstacle among new programs is having a limited number of therapists (as few as two) on a team. Although it is entirely possible to conduct the comprehensive treatment with only two therapists, some providers like to start out more slowly. For example, some providers have begun their program with a weekly therapist consultation meeting and a weekly skills group that is led jointly by the two therapists. The goal in this situation would be to identify ways of achieving the other functions over time. Another common difficulty is that some outpatient providers are unable or unwilling to provide telephone coaching between sessions. If a provider is unwilling to provide telephone coaching, then he or she should not be providing DBT if a client does not have someone to serve as a coach to increase skills generalization. Some private practitioners have developed a two-person team model: Each therapist sees his or her own clients for individual therapy, is available by pager for telephone coaching, and conducts collateral family sessions on an as-needed basis; each therapist also conducts weekly family skills training sessions for the other therapist’s individual clients and their families. The two therapists have a weekly consultation meeting to discuss their difficulties in providing treatment. Even though it may be less than ideal, many practitioners, especially those in rural settings, opt to have weekly consultation meetings over the telephone.

It is not yet known whether these less-than-comprehensive approaches can achieve the same degree of effectiveness as the well-researched comprehensive treatment. Is applying certain elements of DBT more helpful than applying none at all? One study (Linehan, 1993a) found that clients who received comprehensive DBT did better than clients who received a DBT skills group and a non-DBT individual therapy. No one has studied this with adolescents. Anecdotally, we find that the more comprehensive the treatment, the better the outcomes. Hence we suggest that programs or outpatient therapists offer and then provide comprehensive treatment whenever possible. If they start out smaller, they should set a goal to build up the comprehensive treatment model within a reasonable amount of time. One of the biggest obstacles for clinicians starting a comprehensive DBT program is fear that they (1) do not know enough to make it work and (2) will not be able to achieve all of the functions, usually because of the resources available to them. Our opinion is that with proper supervision and consultation, even two motivated therapists can conceivably start a comprehensive program. We certainly encourage teams of two to assertively invite other potentially interested parties to join their team.

DBT as originally described and evaluated (Linehan et al., 1991; Linehan, 1993a) included older adolescents and young adults in the sample, so using the original standard treatment with adolescents is certainly an option. However, when the entire client population consists of adolescents, we and other practitioners have found that several modifications to the treatment are helpful, based on developmental and contextual considerations (Miller, Rathus, et al., in press). In making any changes, we and others have tried to maintain the essence of DBT. In a survey of DBT service providers for adolescents, Miller, Rathus, et al. (in press) found that the most common adaptation is inclusion of families in skills training. Other common adaptations included abbreviating treatment length, simplifying the skills handouts, including skills handout examples that are more relevant to teen females and males, changing the “homework” label, simplifying diary cards, including family therapy sessions, adding new skills relevant to parents or other family members, and conducting an orientation for adolescents’ support networks. Details on these and other adaptations are woven throughout the rest of this book. It is important to note, however, that some adolescent programs follow the standard model and use the standard handouts and diary cards. The central modification, regardless of setting, is to relate all topics and behavioral skills to the issues faced by adolescents while delivering the treatment. Generally we have found that the main factor in determining what adaptations to make is a therapist’s own comfort and experience with materials used.

As an example of one potential outpatient modification, we describe our Montefiore program for adolescents here. The central modifications for adolescents in this program consist of (1) the inclusion of family members with adolescents in a multifamily skills group; (2) the inclusion of family therapy sessions; (3) provision for family members to receive telephone coaching and consultation between skills group sessions; (4) the development of adolescent-family dialectical dilemmas and secondary treatment targets that are addressed in the skills group, as well as in individual and family therapy (described later in Chapter 5 and Appendix B); (5), a reduction in treatment length from standard DBT’s 1 year to 16 weeks, with an optional 16–32 additional weeks of a graduate group; (6) a slightly reduced number of standard skills to fit within the 16-week format; (7) the addition of a fifth skills module, Walking the Middle Path, developed specifically for adolescents and families, and (8) modified handouts, written to present fewer ideas per page in simplified language, and designed to be more “adolescent-friendly.” An overview of the Montefiore program is given in Table 4.3. Below we briefly discuss each of these adaptations and how they work within this program.

To enhance generalization and help structure each adolescent’s environment, we have found it helpful to include family members in skills training sessions. When skills training is conducted as a separate individual session each week, parents may attend this session regularly, for single-family skills training. Depending on the setting, family members can also attend skills training groups or participate in skills training in other ways. In our Montefiore program, we include a weekly multifamily skills training group. Family members were included to increase generalization of skills by training parents and thus allowing them to serve as models as well as potential coaches. Our further hope was to target the invalidating environment directly and enhance family members’ capacity to provide validation, support, and effective parenting. We find that this works well for several reasons—including teaching the family members the same skills at the same time as their children for coaching and reinforcement value; providing in vivo opportunity to role-play skills with the family members; improving ineffective and invalidating interactions from family members; providing interfamily support (both parent to adolescent and parent to parent); reducing the adolescents’ disruptive behaviors in group by having other adults in attendance; and (ideally) enhancing treatment compliance by having parents accompanying their teens into the group.

TABLE 4.3. Overview of Montefiore Program for Suicidal Adolescents

Orientation to mental health clinic and intake evaluation (1–2 visits)

Diagnostic interviewing, history taking, formal behavioral analysis of targeted behaviors

Pretreatment orientation and commitment stage

Teen, teen’s family, and therapist reach mutually informed decision to work together; negotiate a common set of expectancies to guide initial steps of therapy

Adolescents and their families attend orientation group

First phase of treatment—16 weeks

Individual therapy for adolescent

Multifamily skills group for adolescent and family

Phone consultation (individual therapist with adolescent)

Phone consultation (family members with skills group leaders)

Family sessions as needed (usually 4–6 over the 16 weeks)

Therapist consultation meetings (weekly, for treatment team)

Second phase of treatment: Graduate group—16-week modulesa

Graduate group for adolescent (weekly)

Phone consultation (graduate group coleader with adolescent)

Family sessions as needed (typically with group coleader)

Therapist consultation meetings

Individual therapy (in some cases that require ongoing individual work)

Ancillary treatment modes

Note. All aspects of the Montefiore program address the Stage 1 aims of achieving stability and safety, and reducing suicidal behaviors and other forms of severe behavioral dyscontrol.

aClients can contract for additional 16-week modules during the continuation phase, as long as they can identify behavioral goals.

However, some programs conduct separate groups for parents. These might take the form of parallel skills groups in which parents are seen separately but are taught the same curriculum. Alternatively, some programs run separate parent groups with overlapping but not identical content; for example, some parent training, stress management, psychoeducation, supportive, or other material might be brought in. Some of these groups bring parents and adolescents together once every third or fourth week, perhaps for 2 weeks in a row, for conjoint topic presentations. Others keep the groups completely separate and conduct them at different times and on different days. The main reasons for separating parent and adolescent groups include belief in the importance in covering some different material; belief that the inclusion of parents might inhibit adolescents’ self-disclosure (or parents’ ability to speak freely); or, in the case of severely dysfunctional families, belief that family members’ presence might increase emotional and behavioral dysregulation within the group. In one case, we conducted individual skills training for a teen’s parents, paralleling the multifamily skills group, because the parents’ interactions with their teen were so volatile that they would have been strongly disruptive to the group. Chapter 10 details the workings of a skills training group.

Finally, some programs do not include family members in skills training—particularly in settings that make such participation impractical, such as inpatient, residential, or forensic settings. In such cases, practitioners might hold family meetings to orient family members to skills.

Since much of the turmoil in the lives of suicidal adolescents involves their primary support systems (i.e., their immediate families in many cases), we have found it helpful to include family members during some of the time scheduled for individual sessions. This occurs on an as-needed basis when (1) a family member provides a central source of conflict, and the adolescent needs more intensive coaching or support in attempting to resolve this conflict; (2) a crisis erupts within the family and needs immediate attention; (3) the therapist determines that the treatment would be enhanced by orienting/educating a particular family member to a set of skills (if the family member is not attending a skills group), treatment targets, or other aspects of treatment; or (4) the contingencies at home are too powerful for the client to ignore or avoid and continue to reinforce dysfunctional behavior. Typically, a selected family member will attend 3-4 sessions out of the adolescent’s 16 weeks of individual therapy, although on occasion we have had family members attend as many as 12-14 sessions. In addition, depending on the treatment program, some individual therapists will divide their individual sessions in half in order to accommodate the family therapy portion in the latter half. Other therapists may invite the families in for a separate third session during the week (i.e., family therapy in addition to individual therapy and a skills training group). Chapter 9 and Table 9.1 summarize conditions under which it is appropriate to schedule a family session.

When family members will participate in groups, we recommend limiting the number of clients in each group, since parental involvement makes groups about two to three times as large. In Montefiore’s inner-city program, where many teens live in single-parent households, typically 5–6 adolescents per group are ideal, for a total of 10–12 members when family members are included. In our suburban graduate school clinic program at the C.W. Post Campus of Long Island University, and in our suburban private practices in which both parents often attend, we restrict the number of adolescents to 4-5, since this typically results in 10-15 participants in the group. Our rule of thumb is to make sure the skills trainers have at least 4-5 minutes per member to review homework. With a larger size, the leaders risk not having enough time to review the take-home practice exercises. In addition, the leaders are likely to have more difficulty keeping all members engaged in a larger group. A limitation to a smaller group is the periodic absence from the regular rotation of “senior members” who can help to orient new members. Ideally, those who have been there for 8 and 12 weeks tell the new members why they should participate and how the program has been helpful to them. The senior adolescents learn their role from those who precede them. When referrals slow down or clients drop out precipitously, the group develops gaps where there are no new members at a given entry point or a “senior class” is no longer present. This is far from catastrophic, but it is something to keep in mind when providers are forming a group and considering client flow and rates of dropout. In understanding the utility of working with parents or other family members, therapists should note that the inclusion of family members in treatment can actually address all five functions of treatment. By serving as models and coaches of effective behavior, parents can help increase their children’s capabilities, as well as helping with generalization of skills outside the session. When family sessions can address parents’ reinforcement of ineffective behavior and punishment of skillful behavior, clients’ motivation can improve, and gains can be maintained. And working cooperatively with helpful parents can increase the capabilities and motivation of therapists, as well as help to structure the environment to reinforce the clients’ progress.

Of course, adolescents do not always welcome the participation of family members in their treatment. Commonly, there is a background of invalidation and conflict with parents; adolescents may fear that therapy will offer yet another setting in which to be criticized, or yet another personal space that will be intruded upon. They might also wonder where a therapist’s loyalties will ultimately lie if their parents become involved. Adolescents may thus appear sullen and uncommunicative in the initial sessions that include parents. It is thus critical to privately assess the adolescents’ thoughts and concerns about including family members, orient the teens to the role parents will play in treatment, validate any accurate concerns, clarify misunderstandings about the process, clarify issues of confidentiality, and point out the benefits of including parents.

In some cases, family members will not be available to attend an individual session for a variety of reasons. These include conflicting work schedules, transportation difficulties, language barriers, or refusal for other reasons. In such cases, a therapist has several options. One is to determine whether the therapist can help parents solve practical problems in attending by problem-solving with them over the phone. Another is to try again at a later date, rather than giving up completely. Parents’ views on attending or abilities to attend may change. Another option is to solicit the participation of another family member or someone in a caregiver or close interpersonal role, if this is relevant to ongoing work in individual therapy. For example, we have occasionally brought in grandmothers, godmothers, older siblings, and even boy-friends, when we felt it would be beneficial to do so. Finally, a therapist can decide to work with a teen without parental involvement, helping the adolescent to accept this lack of involvement in treatment while at times coaching him or her on effective interactions with the parent(s). See Chapter 9 for an in-depth discussion of the inclusion of family members in individual therapy.

In running numerous multifamily skills groups, we began to observe that family members attending these groups could benefit as much as their adolescents from telephone consultation. This posed a dilemma, since parents in skills training do not have an individual therapist to call. We had no model for this, since standard DBT does not include family members as regular participants in therapy. We decided to offer parents the opportunity to call the skills group leaders, but to limit this to as-needed phone consultations for skills generalization (as opposed to other purposes, such as asking for help appropriately, repairing the relationship, or sharing good news). In cases where one of the skills group leaders is the primary therapist for their child, the parents may only call the other group leader, to avoid placing the child’s primary therapist in a potentially compromised position. In settings in which the primary therapist is also the skills trainer, allowing the parents to call the adolescent’s therapist risks hindering the client’s trust. Thus, in such situations, it may be best to have a policy of setting clear guidelines on what is to be discussed in a therapist–parent skills coaching call that the parent and adolescent agree to, and to follow each phone call with a disclosure of it in the next session. Alternatively, skills coaching for parents may need to be restricted to the context of skills training or family sessions. Even if a parent’s phone coach is someone other than the adolescent’s primary therapist, we encourage parents to tell their adolescent when such a phone contact has been made, so the adolescent remains confident that nothing about his or her treatment is occurring in a deceptive manner.