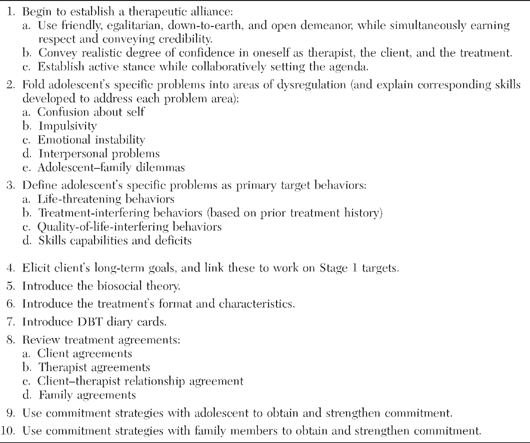

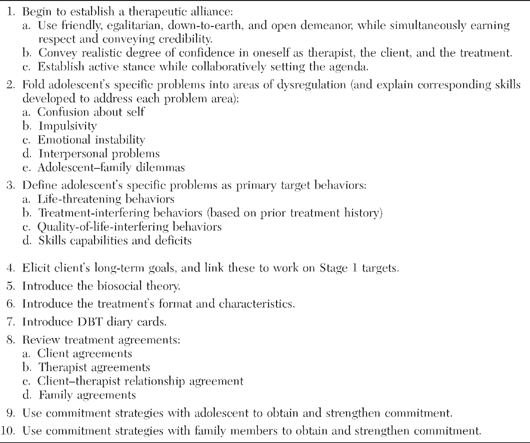

The pretreatment stage of orientation and commitment to DBT begins once suicide risk and diagnostic assessments are complete and the adolescent has been found to meet the inclusion criteria for the DBT program (see Chapter 6). As discussed in Chapter 3, the key goals of this stage are for the client and therapist to arrive at a mutually informed decision to work together and to make explicit their agreed-on expectations about that work. The process involves the primary therapist’s helping the adolescent identify his or her long-term goals, orienting him or her to the treatment, and obtaining the teen’s commitment to treatment. These therapeutic actions are considered “pretreatment targets.” This chapter presents a set of strategies to use with adolescents and families to orient them and obtain their commitment. These are outlined in Table 7.1. In outpatient adolescent programs, an additional orientation to DBT often occurs in a multifamily skills training group format. (See Chapter 10 for orientation to skills training.)

Orientation and commitment to DBT begin with the adolescent alone first. Once the process has been initiated with the adolescent, the therapist can bring in the parents and/or other participating family members and repeat some of the key elements (this can occur late in the first session or in the second session). Even in more restrictive treatment settings (e.g., inpatient, forensic, and residential), we suggest following this same format, despite the fact that the adolescent may not have any choice whether to participate in the DBT program or not. It is important to foster some sense of control over the teen’s participation. For example, the therapist might say,

“We know right now that you do not want to be here. So you can remain miserable, stay in your room, not participate in DBT group or individual sessions, and keep talking to your friend—or you can try to get to know some new people, participate in the treatment, and maybe figure out what you need to do to build a life worth living outside of this place and we’ll help you do it.”

The development and maintenance of a therapeutic alliance with the adolescent are of critical importance in this initial stage and throughout treatment. Other key orientation tasks are (1) to introduce the treatment in terms of how it fits, and can help solve, the individual teen’s problems; (2) to link work on Stage 1 treatment targets with the adolescent’s long-term goals; and (3) to present an overview of the treatment and its requirements. Orientation is not simply a description of the treatment; rather, it aims to build motivation. It is a discussion of what the particular teen can (and can’t) realistically hope to get out of the treatment, and of how the treatment works to fulfill those hopes. The process clarifies the adolescent’s specific goals and the specific DBT procedures used for reaching those goals. This becomes the basis for an explicit treatment agreement to which all parties are asked to commit themselves. Strategies for obtaining client commitment are discussed later in this chapter.

TABLE 7.1. Orientation and Commitment Strategies for Adolescents and Families

Jessica, the 15-year-old introduced in Chapter 6, is typical of adolescents in our outpatient clinic. When her assessments were complete, she met the criteria for the DBT program. She then met alone with the person who was to become her primary (individual) therapist. This began the orientation process.

The primary task at the start of DBT is beginning to develop a collaborative relationship with the adolescent. This is crucial as well as difficult. Many adolescents presenting for treatment initially believe that they do not need it. Even those who have made a recent suicide attempt often minimize it as an impulsive act and state that they “feel better now.” These adolescents often have had conflictual relationships with their parents as well as other adults. Being told that they must talk to a therapist, a stranger, because “something is wrong” makes many teenagers angry, resistant, and noncompliant. Given that up to 77% of suicidal adolescents either do not attend follow-up therapy appointments or drop out of treatment prematurely, it becomes important for therapists to equip themselves with a variety of techniques and strategies to engage such adolescents (Trautman et al., 1993).

A key strategy to working with adolescents involves conveying a down-to-earth, friendly, egalitarian, and open demeanor, while maintaining an understated degree of expertise and credibility. The challenge for therapists entails getting teens both to like and to respect them. In our experience, therapists who have had more experience with adult clients at times approach teenagers with an authoritarian, doctor-like, “one-up–one-down” stance. This approach consistently alienates adolescents. In working with an adolescent, it is also important to communicate a high level of confidence in one’s own ability as a therapist, in the client’s ability to improve, and in the efficacy of the treatment. Feigning confidence in oneself, in the client, or in the treatment will inevitably prove ineffective; a teenager will see through the act and disengage from the treatment. This may pose a challenge for a therapist who is new to the treatment and feels less competent. Thus the therapist should strive for a balance between genuinely communicating confidence in all three domains (self, client, and treatment) and not overpromoting them.

It is important to take an active stance in work with adolescents, especially early in treatment. Therapists who work within other treatment orientations often take a less active stance at the beginning of treatment and allow clients to choose freely what to discuss. In standard DBT, as well as in DBT with adolescents, the therapist uses these early sessions to get to know the client and to allow the client to get to know the therapist. This active stance is part of a dialectic, however, since one of the biggest mistakes that a novice DBT individual therapists tends to make is forcing an agenda on the client instead of letting the session unfold and skillfully weaving in the necessary components identified below. Thus taking an active stance involves the therapist’s developing a plan for the session content with the client and then guiding the client through this content, as well as adhering to DBT principles. Setting an agenda at the beginning of the session is a customary part of most forms of CBT. Although DBT does not require agendas, it can often be helpful to lay out at the beginning of a session which tasks and topics need to be covered. It also gives the adolescent a chance to say what topics he or she wants to cover. In the first or second session, which may include assessment, orientation, and commitment, the therapist will set the agenda by stating, “Jessica, I want to get some history and hear what problems you may currently be having before we decide what is the appropriate treatment for you.” Some beginning therapists feel compelled to tell clients everything they are supposed to cover in the first session, as opposed to skillfully weaving the material into the first couple of sessions.

One stylistic strategy in DBT is the use of irreverence—a style characterized by calling a spade a spade, as well as by using humor, sarcasm, or confrontation. Whereas some therapists are wary that being “too” irreverent early in therapy might alienate teens, we believe exactly the opposite. We recommend weaving irreverence into treatment immediately, since it functions to get adolescents’ attention in a manner different from most others with whom they discuss their problems. For example, when Jessica nonchalantly discussed her suicidal behaviors and her ambivalence about discontinuing them, the therapist stated, “Jessica, you realize that this treatment will not work if you are dead.” Irreverent communication strategies are discussed further in Chapters 3 and 8 as well as in Linehan’s (1993a) text.

The orientation session begins with asking for a recap of the client’s problems. Hence it is important to validate the client’s potential frustration at having to repeat his or her story to yet another mental healthcare provider. This is relevant only if the primary therapist is different from the initial evaluator. For example, the therapist might say,

“Jessica, I know you already told a lot of this information to Liz, who spent 3 hours with you last week during the diagnostic evaluation. She did share much of that information with me; however, if I am going to be your individual therapist, I want to get to know you, your strengths, and your weaknesses, and I will probably be asking at least some of the same questions. So bear with me.”

As the session proceeds, the therapist folds the client’s problems into the five major problem areas identified on Figure 7.1. These problem areas correspond directly to the areas of dysregulation associated with BPD (i.e., emotional, behavioral, cognitive, interpersonal, and self; see Chapter 3). We describe the five problem areas as follows: (1) confusion about self, (2) impulsivity, (3) emotional instability, (4) interpersonal problems, and (5) teenager-family dilemmas. For example, if a teen identifies sudden and apparently baseless anger as a problem, the therapist might say,

“Jessica, when you are feeling OK one minute and then angry for seemingly no reason, DBT therapists call that a ‘problem with regulating emotion’ or ‘emotional instability’ (Problem 3 on the handout). Since you don’t know why your emotions shift sometimes, you probably experience some confusion about yourself (Problem 1 on the handout). If you then start cutting yourself or purging without thinking about the consequences, we consider that impulsive behavior (Problem 2 on the handout).”

The therapist will review the other problem domains if the adolescent does not raise them naturally during the first session. Typically, adolescents referred to our program endorse at least four out of the five problem areas.

“Jessica, do you find that your relationships—with your boyfriend, your parents, your sister, your friends—run hot and cold? That is, even though you have friendships, do you find it hard to keep these relationships stable? Is it hard to get what you want from these relationships? If so, that would be Problem 4—interpersonal problems. And Problem 5 relates to teenagers who feel that they don’t see eye to eye with their family members. Do you feel you’re on one side of the Grand Canyon and your family members are on the other side, and it is difficult to understand one another and come to an agreement on issues, such as curfew, dating, homework, or body piercing?”

The DBT therapist then tells the teen that although having these problems may feel overwhelming, there is some good news:

“For each of these problems, the skills group will teach you specific skills that will target and reduce your specific problems. For example, in regard to impulsivity, we are going to teach you distress tolerance skills so that you will learn how to distract and soothe yourself when you have urges to kill yourself, cut yourself, overdose, drink alcohol, or purge. When you say you have interpersonal problems, we are going to teach you a set of interpersonal effectiveness skills in order to help you keep your self-respect; you’re your relationships stable; and get what you want from your boyfriend, your girlfriends, and your parents. Do those skills sound helpful?”

FIGURE 7.1. Handout on DBT for adolescents and family members.

In addition to what takes place in individual therapy, the skills trainer briefly reviews each problem area as it relates to each individual client and then describes the corresponding skills module, one by one. This review typically instills hope in the adolescent and family.

The individual therapist (who may or may not be the same clinician as the diagnostic interviewer, as noted earlier) is responsible for eliciting the information relevant to the DBT Stage 1 targets. Much of this information may have already been gathered during the diagnostic evaluation. The therapist connects the client’s specific problems with DBT’s primary target behaviors. The therapist might say, “So those overdoses are considered life-threatening behaviors, and your depression, your bingeing and purging, your school problems, and your intense conflicts with your parents are what we call ‘quality-of-life-interfering behaviors.’ Is it your belief that these problems interfere in the quality of your life?” Reframing these problems in DBT language enables the therapist to explain how DBT will be able to target these problems, while also beginning (unobtrusively) to teach the client this language.

Once the primary target behaviors are identified, the DBT therapist is then able to review the Stage 1 treatment target hierarchy and informs the client that individual sessions will be organized accordingly from that day forward. To make this point clear, the therapist may draw a pyramid and list the client’s problem behaviors from top to bottom in a fashion corresponding to the Stage 1 hierarchy (see Figure 7.2). It is explained to the adolescent that if in the past week there have been any self-injurious behaviors or increases in suicidal ideation, those behaviors will need to be analyzed first. The therapist goes on to explain that it does no one any good if the therapist and client spend the session talking about issues unrelated to the self-injury, since the client may intentionally or accidentally kill him- or herself by the next visit if they do not understand what is going on and how to deal with it differently. The remaining targets are then discussed, in hierarchical order.

In obtaining a commitment to reducing such Stage 1 target behaviors as suicide and self-injury, drug use, and truancy, as well as increasing behavioral skills, it is critical for the therapist to link them to the adolescent’s long-term goals. Thus it is always important to elicit these goals. Jessica’s goals included graduating from high school and starting college, continuing her cheerleading activities, joining a band as a singer, getting married, having kids, and finding a high-paying job. Jessica agreed not to kill herself, but was initially reluctant to reduce her self-cutting, since the behavior helped distract her from her intense anxiety and sadness. The therapist then queried Jessica as follows:

THERAPIST: You mentioned that you are self-conscious about the marks on your arms and legs. If we could figure out a way for you to reduce your anxiety and sadness without leaving cuts and scars on your body, would you choose another method?

JESSICA: I don’t know…I know this works.

THERAPIST: I get that…and if you want to continue your cheerleading next year, I imagine it may be hard to wear long sleeves and pants to cover those marks. And I also know that while you initially experience relief when you cut, you also often experience shame later. This becomes a vicious cycle for many people and makes them more vulnerable to cutting again…Does that happen to you?

JESSICA: Yes, I often feel worse. I know I have to work on this, but I am so scared to give it up.

THERAPIST: That makes perfect sense to me, given how effective this behavior has been for you in the short term at reducing certain negative emotions. I feel confident, though, that if I can teach you some new skills and we try them out, we’ll find some of them will help you in similar ways to cutting, without leaving those marks or creating the negative emotions that perpetuate the problem as well.

FIGURE 7.2. Jessica’s Stage 1 target pyramid drawn in session.

Referring back to the five problem areas listed on Figure 7.1, the therapist asks the adolescent rhetorically, “How do you think you developed these types of problems?” Typically, the adolescent is baffled and somewhat demoralized by the rhetorical question. To help answer this question, we explain that Marsha Linehan, the originator of DBT, developed a theory that helps explain why some people have these types of problems (Linehan, 1993a; see Chapter 3 for a full discussion of the biosocial theory). Using visual aids such as a handout can help adolescents better understand this abstract theory. The therapist first reviews and defines the two components of the theory: “bio” and “social.” “Bio,” derived from the word “biology,” involves the biochemistry of one’s brain. The therapist might ask, “Jessica, have you ever experienced yourself as more emotionally sensitive, quicker to react, and slower in returning to your emotional baseline once you get upset than your siblings or friends?” Indeed, most of these adolescents admit that little things seem to “get under their skin easily” and affect them more than their peers. Moreover, they acknowledge that when they get upset, their emotional reactions are more intense and reactive (e.g., not just a little sad, but feeling very depressed; not mildly anxious, but having panic attacks; not merely irritated, but experiencing angry outbursts). The third characteristic—slow return to emotional baseline—is explained by drawing a graph on a piece of paper, with a line halfway up the bell curve to represent the adolescent’s moderate to high level of emotional arousal. Instead of returning back to 0, the line remains elevated at this level for an extended period (sometimes hours or even days). Many teens endorse this characteristic as true of themselves as well. Jessica reported, “Sometimes when I get really angry, it takes me almost a whole day to chill.”

The “social” part of the theory is described as the “invalidating environment.” Once “validation” and then “invalidation” are defined, an example is provided immediately to help illustrate the concept of invalidation. The therapist attempts to use examples offered by the adolescent during the first session if possible:

“Jessica, you told me that whenever you feel depressed and you feel you have less energy to do your chores in the house, your mother calls you a crybaby and tells you to snap out of it, or you’ll get a beating. You also told me that when you travel with your father to visit your relatives in Puerto Rico, your father insists that you put on a smile even if you are not in a smiling mood. These experiences are examples of ‘invalidation’—in other words, communications indicating that your thoughts, feelings, or actions are wrong, inappropriate, and invalid.…Who’s to say how you should feel and act and what you should think? Those are your thoughts and feelings, not theirs!”

Jessica responded, “I’m so used to it, I guess I never thought of it that way.” The therapist emphasizes that invalidation occurs frequently, to varying degrees, and can often be inadvertent. The therapist also explains the transactional nature of the biosocial theory (see Chapter 3), emphasizing a nonjudgmental and nonblaming attitude. For example, a mother and child may have different temperaments, as in the case of a quiet, shy, mellow toddler unmatched temperamentally with a gregarious, high-energy, demanding mother, or a highly emotional child with an emotionally controlled parent. Some teens tend to protect their parents in response to this explanation of an invalidating environment. The therapist can suggest that parents who invalidate often learned it as children from their own parents and do not know any way to communicate more effectively. If this is applicable, the therapist might state, “It makes perfect sense that your parents invalidate you, since that is what they learned growing up.” The therapist then has an opportunity to point out the intergenerational transmission of invalidation. Aditionally, teens sometimes invalidate their family members as well.

Regardless of the intent, the therapist targets the invalidation experienced in the family, in order for the adolescent to feel better understood by the family and for the family members to feel better understood by the adolescent. (The biosocial theory review, like other aspects of orientation to treatment, typically occurs first with the adolescent alone and then is reported with the entire family.) The therapist then continues, “Here’s the good news: Now is the time for you (and your family) to learn how to validate one another properly, and to put an end to the inadvertent invalidation that occurs in your household each day. You, Jessica, and each member of your family have to take responsibility for becoming more aware of this behavior and practicing the skill of validation.”

For many adolescents, hearing the biosocial theory explained is the first time they understand why they act and feel the way they do. Some adolescents are literally moved to tears by the experience.

The therapist reviews the treatment format next, consistently checking in with the client to ensure that he or she understands what is being said. Then the therapist attempts to obtain initial commitment to the various treatment modalities (see the later discussion of commitment strategies), using a conversational yet didactic style. A therapist would introduce the 16-week Montefiore program as follows:

“Jessica, our DBT program is two sessions per week for 16 weeks.1 The treatment consists of one individual session (for 60 minutes) and one multifamily skills training group (for 2 hours) per week. So since you live with your mom, and you and she have a lot of conflicts, I think it makes sense to invite her as the family member who will attend the multifamily skills group with you. Don’t you agree? Also, the individual session is periodically divided in half, so that we can have some time to address family issues with your mom, your dad, and even your sister. How does that sound to you? The bottom line is that you and your family will be treated by a team made up of your individual therapist, two skills trainers, your prescribing psychiatrist, and other DBT therapists in our program.

“The first phase of treatment lasts 16 weeks. When you finish that, you could be eligible for the graduate group, which involves a lot of fun activities and is only for people who graduate from the first phase. Another important component of the treatment is the telephone coaching. There are three reasons I would like you to call me. First, I want you to page me before you engage in a problem behavior, like cutting, overdosing, purging, or drinking. It doesn’t help to call me afterwards, since you already decided how to handle that situation. Second, I want you to call me with good news. I love to hear good news—and you can leave a message on my machine and I will be thrilled to get it. Finally, I want you to call me if you feel that we have to repair our relationship [see Chapter 3 for further explanation]. Some teens have trouble with this pager idea…they say, ‘I didn’t want to call you and bother you on the weekend.’ Jessica, let me be crystal-clear: I wouldn’t be instructing you to call me if I thought it was a problem. If I am tied up with something else when you page me, I’ll tell you so and let you know how soon I can call you back. Does that seem reasonable? Good. So I’d like to have you practice paging me this week, at some point when you’re not in crisis, just to see how this whole thing works. Don’t worry, I won’t keep you on long—just to say hello. Can you we do a practice page on Tuesday night?”

The practice page helps the client add this new skill to his or her behavioral repertoire during an undistressed period, with the hope that he or she will be more likely to use it when actually faced with a stressor.

The therapist then says to the client enthusiastically, “If we work together as a team, I can help you solve your problems. There are several key points you need to understand as we move ahead.” The therapist describes seven characteristics of DBT to the adolescent in the first or second individual therapy session. We list them below, with sample therapist descriptions for the client:

1. DBT is not a suicide prevention program, but rather a life enhancement program. Although the therapist acknowledges the client’s misery and concedes that suicide provides one way out of suffering, he or she emphasizes that the alternative is to make life more livable. “The bottom line is that I cannot keep you from killing yourself if you are intent on doing so, but I can help you create a life worth living.”

2. DBT is supportive of clients’ attempts to improve the quality of their lives. “Jessica, I want to support you to achieve your goals in any way I can.”

3. DBT is behavioral. “In order for you to change your life and achieve your goals, you are going to have to decrease some of your old problem behaviors, and begin to increase new skillful behaviors that you’re going to learn in DBT. Given your depression and anxiety, I think you will find it interesting to know that by changing your behavior, you can actually change your emotions.”

4. DBT teaches skills. “As you know from your cheerleading and piano lessons, it will take practice to get good at these new skills.”

5. DBT is collaborative. “We’re going to work as a team to help you achieve your goals. Clearly, you haven’t been able to get there yet without help, and I know that I will not be able to help you if you don’t pull some of the weight…so I feel confident that if we work together, we can do it.”

6. DBT employs telephone consultation. In the first session, the therapist gives the client his or her phone number or pager number and explains the three reasons for phone calls in DBT (see above). To emphasize this point, the therapist can use the metaphor of a basketball player and coach. “Jessica, you’re a basketball player [the therapist identifies Jessica’s favorite player and calls her by that name]. You’re dribbling down the court, your team is down by 1 point, and there are 20 seconds left. As you dribble past half-court, the other team sets up a defense, and you feel stuck. What do you do? You call a time out and check in with your coach to figure out how to get unstuck, instead of getting trapped and turning the ball over. Similarly, in life, when faced with a very tough or unfamiliar situation, I want you to call a ‘time out’ and call your coach—that’s me—so that I can help you get out of sticky situations without making things worse.”

7. DBT is a team treatment. “Here’s more good news: I am not treating you alone. I have a team I talk to every week. The team is made up of me, your individual therapist; the skills trainers; and other DBT therapists who work in this program. Their job is to make sure I deliver the best possible treatment to you. You’ve got me to help you, and I have the team to help me.”

Introduction of the diary card (see Figure 7.3) typically occurs at the end of the first session or during the second session. (The two-page card can be photocopied and trimmed down to fit on one 8½× 11 page.) The client is told that the diary card is a crucial component of the therapy, and that he or she is expected to complete it and return it to the therapist each week. The therapist explains the rationale for the diary card by explaining its several extremely important functions.

From Dialectical Behavior Therapy with Suicidal Adolescents by Alec L. Miller, Jill H. Rathus, and Marsha M. Linehan. Copyright 2007 by The Guilford Press. Permission to photocopy this figure is granted to purchasers of this book for personal use only (see copyright page for details).

FIGURE 7.3. Adolescent diary card.

First, filling out the diary card daily requires the client to self-monitor target behaviors, emotions, and skills. In and of itself, this is an intervention that may help reduce problem behaviors while also serving as a consistent mindfulness skills practice exercise. Second, the card functions as a general overview of the client’s week, so the therapist and client have a “week at a glance.” This helps reduce the risk of overlooking any primary target behaviors. Third, the card functions as a “diary,” in that it helps keep a more accurate record of the adolescent’s daily emotions and behaviors than would the adolescent’s memory alone, especially 7 days later. Fourth, the diary card enables the client and therapist to perceive potential links between emotions and maladaptive as well as adaptive behaviors. Fifth, the diary card is the primary tool used at the beginning of every individual session to help focus the session content. The therapist states,

“I really hope we can figure out a way for you to remember to complete and return your diary card each week…because if you forget your diary card, I will have to ask you to fill out a blank one in session, and then we’ll have to figure out what interfered in your ability to complete and return it. That will take up a good portion of our session time, and I would much rather use your time to discuss other issues happening during the week. Wouldn’t you?”

In order for the adolescent to learn how to complete the diary card, the therapist asks the client in session to remember the previous day and to rate any maladaptive behaviors and emotions listed on the card, starting from left to right. The therapist clarifies the difference between “self-harm urges and actions” and “suicidal thoughts and actions” by highlighting the presence of suicidal intent as the sole criterion. Typically, the adolescent is instructed to complete only a portion of the diary card for the subsequent week. This helps the adolescent avoid feeling overwhelmed by the fairly complex card and potentially helps to build mastery. Moreover, the door-in-the-face commitment strategy (see below) is effectively used around this issue. Expecting an objection, the therapist first tells the adolescent to complete the entire card for the following week. When the teen states that it is too much work, the therapist makes a deal and says, “how about completing just half the card for this week?” Usually the adolescent sees this as a bargain. Furthermore, it constitutes a relatively easy homework assignment and thus provides the therapist with something to positively reinforce at the beginning of the next session.

In addition to standard behaviors, such as suicide attempts, NSIB, and risky sexual behaviors, the diary card for adolescents should also include age-appropriate targets and should be tailored to each individual client. Hence we have added to the adolescent diary card a “Cut class/school” column, along with some blank columns. For some teens, we track binge and purge urges and behaviors. For other teens, we track assaultive urges, dissociative behaviors, and/or invalidating statements toward self and others. When teens rate these behaviors (and emotions) on a 0–5 scale, they are instructed to rate the “most intense” urge or affect, instead of the “average.” Often, for example, the average anger on a given day might fall at about 3 on the 0–5 scale, and it becomes difficult to assess those days when anger was clearly most intense. For those clients who report high urges and emotions all day nearly every day (5’s), the therapist might encourage the client to track the “average” as well as the “most intense” rating each day, in order to differentiate one day from another.

A common mistake made by a new DBT therapist is forgetting to troubleshoot after obtaining initial commitment that the adolescent is going to fill out the diary card during the week. The therapist should say something like this:

“Jessica, now that you have agreed to complete the diary card, what might interfere with your getting it done and then bringing it back here next week? Let’s think about some potential obstacles.…For starters, what time of the day do you think you might fill it out? Where will you keep it each day and night? How will you remember to leave home with it next Wednesday, so that you can bring it to our session?”

We often suggest to teenagers who do not have an opinion that filling out the diary card before bed, and leaving it in a place near the bed or desk, is a good idea. Also, we suggest that they write a note and leave it on the refrigerator or bathroom mirror so that they cue themselves to (1) fill out the diary card each day and (2) bring the diary card to therapy.

Many teens exhibit initial noncompliance with completing their diary cards. Common reasons for this noncompliance include, but are not limited to, (1) not understanding the rationale for the diary card; (2) not understanding how to fill out the diary card properly; (3) feeling as though they do not have the time to complete the diary card; (4) feeling angry about having more “homework”; and (5) worrying about their parents’ sneaking a peek at their diary cards (which are supposed to remain confidential). Understanding what is interfering with completion of the diary card is crucial.

Because some teens have initial difficulty with completing the diary card, therapists must remember to employ the principle of shaping. Getting the teens to bring in a portion of the diary card filled out is a good start. For those who have trouble with that, sometimes simplifying the diary card is indicated. In addition, it is often necessary for a therapist to ask a client after a week or two of noncompliance, “Remind me again why I am assigning this work for you to do at home. Am I doing this to be a pain in your neck, or are there other reasons?” A more thorough behavioral analysis may be indicated at this point to assess the function of the non-compliance. Therapists must be careful not to be shaped by their clients’ noncompliance into not asking for and obtaining a diary card each and every week! It is equally important for therapists to remember that clients may feel shame when they do not complete the diary card, just as they may experience shame when they do—since completing the diary card “forces” them to acknowledge certain behaviors and emotions that they have been trying to avoid.

Orientation cumulates in a set of agreements that spell-out the responsibilities and goals for all parties involved, including families. Client, therapist, and family agreements are typically presented and discussed during the second or third session. Client agreements, which may overlap with but are not necessarily the same as addressing the specific target behaviors identified on the treatment plan, are made orally and include the following: (1) to enter and stay in therapy for a specified length of time (e.g., 16 weeks, 6 months, or 1 year, depending on the program); (2) to attend both individual therapy and group skills training (the therapist should review the attendance policy); (3) to work on reducing specific life-threatening, therapy-interfering, and quality-of-life-interfering behaviors that have been identified during the initial assessment and orientation, while increasing behavioral skills; and (4) to page the therapist for coaching as needed.

Implicitly and explicitly, the therapist agrees (1) to make every reasonable effort to be effective; (2) to act ethically; (3) to be available to the client (both for sessions and by pager); (4) to show respect for the client; (5) to maintain confidentiality, with the exceptions of (a) suicidal or homicidal ideation with plan and intent (to be reported to the clients’ legal guardian) and (b) suspected physical or sexual abuse or neglect (to be reported to child protective services as mandated by state law); and (6) to obtain consultation as needed from supervisors and colleagues attending the therapist consultation team meetings.

The client-therapist agreement with adolescents is introduced by dialectically highlighting omnipotence and impotence:

“Jessica, I know as a DBT therapist that I am pretty darn good. However, I am not perfect. I make mistakes. I am confident, therefore that I will do something during treatment that will bother you, piss you off, and maybe even cause you to question continuing in therapy. Now let’s be clear: I expect you will make mistakes, you may do things that piss me off, and so on. The point I am making here is that if you are going to get the help you need, we both need to be sure that we keep the therapeutic relationship strong. That requires both of us to be honest with the other if we feel there is a problem. If one of us upsets the other (even accidentally), we have to say to the other person, “Hey, when you said that, you pissed me off,” or “Hey, why didn’t you call me when you said you would?”

Given that suicidal adolescents typically drop out of treatment at very high rates, it is imperative for the therapist to raise these relationship issues on Day 1, and to obtain commitment from the teen and demonstrate personal commitment to attend to them as the treatment progresses.

Lastly, when families are involved in DBT, it is equally important to review agreements pertaining to them as well. We develop an oral agreement with family members that includes the following (1) to attend and actively participate in a multifamily skills training group (or family skills training); (2) to participate in family therapy sessions on an as-needed basis; (3) to facilitate transportation for the teen, either by driving him or her to scheduled appointments or by providing money for public transportation; and (4) to observe rules of confidentiality by not asking the primary therapist to provide specific information gleaned from individual sessions. Parents are told that they can feel free to leave messages on the primary therapist’s answering machine or speak to the therapist directly to give relevant information. Parents are also reminded about conditions for therapists to break confidentiality. At times, the therapist may choose to tell the client that the parents left a message and share the contents of that message, especially when there is a serious concern (such as a suicide attempt, suicidal ideation, or increasing depressive symptomatology). When less dire messages are left, the therapist uses his or her judgment concerning whether to bring that information into the session or not. We provide further discussion of handling confidentiality between teens and their parents in Chapter 9 (see especially Table 9.4).

In our experience, inadequate commitment by the client, therapist, or both leads to many therapy failures and early terminations. The client may make an insufficient or superficial commitment in the initial stages of the change process—or, more likely, events both within and outside of therapy may conspire to reduce strong commitments previously made. This last point particularly relates to working with adolescents, since they are usually residing in their invalidating environments and often feel hopeless about any improvement in their situations. Client commitment in DBT serves as both an important prerequisite for effective therapy and a goal of the therapy. Thus a therapist does not assume a client’s commitment. DBT views commitment as a behavior itself, which can be elicited, learned, and reinforced. The therapist’s task thus includes figuring out ways to help this process along. When working in a clinic in which treatment is potentially short-term, the therapist must figure this out quickly (Miller, Nathan, & Wagner, in press).

In-session behaviors that are inconsistent with an initial degree of commitment and collaboration include refusing to work in therapy, avoiding or refusing to talk about feelings and events connected with target behaviors, and rejecting all input from the therapist or attempts to generate alternative solutions. At these moments, the commitment to therapy itself should be targeted and discussed, with the goal of eliciting a recommitment. The therapist cannot proceed further without it. Remember, problems other than commitment may underlie these behaviors; thus, a behavioral analysis is indicated.

Often adolescents have not come voluntarily for treatment. They may be forced into treatment by parents or schools (which may not allow the adolescents to return if they are not in therapy), or treatment may be mandated by courts or child welfare agencies. Thus obtaining a commitment can be a particular challenge; however, without it treatment cannot begin.

Eliciting commitment necessitates a certain amount of salesmanship. The product being sold is new behavior and sometimes life itself. When treatment is mandated by the courts or by an adolscent’s parents, sometimes the therapist’s only course of action is to say, “OK, I know you don’t want to be here. Would you feel any better if we could figure out a way to get the court [or your parents] off your back? Yes? Great. So what has to happen before they get off your back? Let me help you with that.” Although we hope to obtain a full, enthusiastic commitment to any and all target behaviors, we often settle for a partial commitment to one or two target behaviors, with the hope of obtaining a deeper and broader commitment as the treatment progresses. It is useful here to remember a key DBT maxim: “DBT therapists get what they can take and take what they can get.”

To obtain commitment to DBT, the therapist needs to be flexible and creative while employing one or more of the following commitment strategies: (1) selling commitment: evaluating pros and cons; (2) playing devil’s advocate; (3) the foot-in-the-door and door-in-the-face techniques; (4) connecting present commitments to prior commitment; (5) highlighting freedom to choose and absence of alternatives; and (6) cheerleading (Linehan, 1993a).

In evaluating the pros and cons of proceeding with treatment, the therapist wants (1) to review the advantages of the decision to proceed, as well as (2) to develop counterarguments based on reservations that are likely to arise later, when the client is alone and has no help in diffusing doubts. For example, the therapist might say,

“Jessica, by making a commitment to treatment, we will work together to help you achieve your goals of reducing your suicidal and self-injurious behaviors; reducing your drinking, depression, bingeing, and purging; decreasing your problems with your boyfriend and parents; and helping you stay in school so that you can graduate. Now let’s think together about the cons of making this kind of commitment. It is going to take a huge effort to change some of your long-standing behavioral patterns. Plus the time commitment necessary for group and individual sessions, as well as therapy homework assignments and phone consultations, may be too much for you right now…so we should think about both the pros and cons before you make a final commitment. Whenever I have to make an important decision, I try to weigh the pros and cons.”

Often therapists start with the cons and then identify the pros, since many teens are already starting from the “con” side of participating in treatment. The therapist may want to highlight cons to treatment if the adolescent has forgotten some standard ones, such as having less free time, doing homework for therapy, and stirring up intense emotions. It is important for the therapist to highlight the short- and long-term nature of each pro and con, since participating in treatment often looks less compelling in the short term. Many teens have trouble considering the “long term.” Some teens are unable to visualize their lives 2 or 3 years from now; therapists may have to help such clients “stretch” their imaginations to weeks and months, and visualize the pros and cons from that vantage point.

In the devil’s advocate approach, the therapist poses arguments against making a commitment to treatment, with the intent that the client will make his or her argument for participating in treatment. The therapist might say, “Jessica, this treatment requires a huge time commitment and a good deal of work…and I am not sure that you are up to it right now” or “… wouldn’t you rather be in a treatment that wasn’t so demanding?” This technique becomes quite useful with teenagers who are more likely to offer simplistic “blanket” agreements, such as, “Oh, yeah, I definitely want to do this therapy…And, yes, I will never cut myself again.” Therapists want adolescents to argue for the therapy by building a strong case for themselves: “I do want therapy now, because my life is a wreck, my parents are going to kick me out of the house, I am already on probation at school, and my drug problem is getting really out of control. I don’t know if I’ll have another chance before it’s too late. I gotta get help and get it now.”

The foot-in-the-door and door-in-the-face techniques are well-known procedures from social psychology that enhance compliance with requests. In the foot-in-the-door technique (Freedman & Fraser, 1966), the therapist makes a request that seems easy, followed by a more difficult request. For instance, a therapist first got a client with social phobia to agree to attend group skills training. Then the therapist said, “OK, now that you are there, can you volunteer to report on your homework, or at least read something from the skills notebook when the skills trainers ask for volunteers?” Here is another example: In the first session, after the therapist gets the adolescent to commit to participate in treatment and work on all target behaviors, the therapist then says, “Oh, by the way, there’s one more little thing I would like you to do for next week…it’s called a diary card.” At that point, the therapist reviews the card.

Still another example of the foot-in-the-door technique involves maladaptive behaviors that the client does not want to address. One therapist said to a suicidal adolescent with alcohol abuse and marijuana use, “OK, I understand you do not think marijuana is a problem for you. I am not clear one way or another. So let’s not have you try to reduce it. How about if you merely track your use on the diary card like you do your alcohol use, which we agree you are trying to reduce. OK?” As previously discussed, self-monitoring is the first step to ultimately reducing any behavior.

In the door-in-the-face technique (Gialdini et al., 1975), the therapist first makes a harder request, and then solicits a more easily performed behavior. This strategy proves helpful in obtaining early commitment to treatment and to reducing suicidal behavior and NSIB. For example, with one teen who was angry about being “dragged to a shrink,” this strategy was helpful: the therapist slowly reduced the length of his commitment from 16 weeks to 2 weeks, and it was agreed that treatment would focus on “how to get your parents off your back.” Regarding a commitment to stop suicidal behavior, Jessica would not agree to stay alive for the entire length of the program (i.e., 16 weeks), but she could make a commitment not to end her life for the next week. The therapist said, “Jessica, how about if you agree to stay alive this week, and we will reevaluate next week to see if you are willing to renew your agreement?”

Another example of the door-in-the-face technique is often used with the diary card (see Figure 7.3). This strategy can also be useful in the skills training group as well. For example, one afternoon one of the group members entered the group room 2 minutes early—but he chose to sit away from the table (where everyone else sits), looking agitated, with the hood of his jacket covering his face. The skills trainer asked, “Alan, would you please come sit at the table, pull your hood off your face, and lead us in a mindfulness exercise?” Alan said, “I ain’t doing all that!” The therapist seemingly relented by saying, “How about if you just come to the table and lower your hood, then?” The client said, “All right.” In this case, the therapist never expected the client to agree to all of those requests and lead the mindfulness exercise. But making an additional, more challenging request at first led to increased compliance when the therapist then asked Alan for less.

When the therapist has a sense that the commitment is fading, or when the client’s behavior is incongruent with previous commitments, the therapist can remind the client of commitments made previously. For instance, when Jessica threatened at one point to use laxatives again, the therapist said, “But I thought you were going to try your best not to do that ever since you made that commitment 6 weeks ago? That’s one of the commitments you made upon entering therapy with us.”

The strategy of highlighting freedom to choose and absence of alternatives is particularly useful for working with all teenagers, but especially for those who are in treatment involuntarily or who are not particularly interested in treatment at this point. The idea behind this strategy is that commitment and compliance are enhanced when people, especially adolescents, believe that they have chosen freely and when they believe there are no alternatives to reach their goal. Hence the therapist should enhance the feeling of choice, while at the same time stressing the lack of effective alternatives. For example, in developing or redeveloping a client’s commitment to stop attempting suicide, the therapist may emphasize that the client is free to choose a life of coping by suicide—but that if he or she makes that choice another treatment should be found, since DBT requires reduction of suicide attempts and NSIB as a goal. When using this strategy to strengthen commitment to the treatment program, the DBT therapist attempts to list in graphic form all of the problems the teen is currently experiencing and then says,

“Jessica, you can try to manage your suicidality, depression, substance use, disordered eating behaviors, school problems, and huge conflicts with your boyfriend and parents on your own as you have been doing. The other option is to try this therapy twice per week and see if we can get these problems under control, so that you can stay alive, get your parents off your back, and remain at home and school instead of being sent to residential treatment.…Of course, it’s totally your choice, since this is your life! What do you think?”

The purpose of cheerleading is to generate hope. One of the major problems confronting suicidal adolescents with BPD or borderline features is their lack of hope that they can effect change in their lives. In cheerleading, the therapist encourages the client, reinforces even minimal progress, and consistently points out that the client has the qualities needed to handle his or her problems. For example, Jessica was raised in a family in which the primary coping and problem-solving style was to attempt suicide. This became a learned response that seemed to be passed from generation to generation. Another client was raised by an emotionally abusive, alcoholic father who continued to demean and insult her. Both of these clients needed extensive amounts of cheerleading and encouragement to help build a sense of hope that they could actually change themselves and alter (somewhat) their oppressive home environments.

Instilling hope is intimately connected to getting an initial commitment to treatment and recommitment when needed. Cheerleading may also be required when the devil’s advocate technique falls flat. With Jessica, the therapist aggressively employed the devil’s advocate technique by saying, “This does not seem to be the right time for you to work on these problems…maybe you can recontact the program when you feel more ready to work on all of your problems.” Jessica started to agree with the therapist and looked dejected. The therapist quickly responded with “You know, however, I do get the impression that when you do put your mind to something you can do extremely well, as you used to do in school, choir, and cheerleading. Is that true? If so, then if you really and truly put your mind to working at this treatment, like you do in other areas of your life, I bet you will start to feel better. What do you think?” Jessica was buoyed by these last comments and was more able to make a firm commitment to the treatment program. The devil’s advocate technique and cheerleading can be used in a dialectical fashion to build commitment.

The periodic and intense hopelessness of these clients can overwhelm a therapist. At these times, the therapist consultation meeting becomes critical in helping the therapist reestablish commitment, perspective, and balance. Many therapist teams make good use of cheer-leading to enable their weary colleagues to continue treatment effectively.

After orienting and obtaining commitment from the adolescent, the therapist invites the family members in for the latter portion of the first session (or a portion of the second section) to begin orientation and commitment with them as well. First, the therapist reviews the handout illustrating the five problem areas and corresponding skills modules (Figure 7.1), and asks the adolescent to identify which of the five problem areas applies to him or her. Then, in order to instill hope in the family members just as was done with their child, the therapist makes the connection between the problem areas and the corresponding skills modules specifically developed for those behavioral problems and taught in skills sessions (e.g., multifamily skills group, family skills training, individual skills training). Depending on the particular family issues as well as time remaining in the session, the therapist may choose to ask the parents whether they believe the skills being taught in the multifamily skills training group may be helpful to them as well (see Chapter 9 for an extended discussion), especially given the heightened stress in the household. In many cases, identifying parents’ own current and/or past problem areas occurs in the family skills training sessions.

The therapist then orients the family members to the treatment format, including the modes of treatment. Parents are strongly urged to participate in the 2-hour multifamily skills training group for the duration of treatment. Exceptions are made when certain employment and language barriers exist. If a parent is at risk of losing his or her job if time is taken off even after a medical letter is provided, we will make an exception. In addition, exceptions are made for parents who are monolingual in a language other than English, since we cannot translate the entire skills group content in a 2-hour time period. In either of these cases, parents unable to attend the skills group are expected to spend extra time in family sessions reviewing skills and having their own child teach them some of the content when appropriate. The other modes of treatment are briefly reviewed: weekly individual therapy, family therapy as needed, telephone consultation, and the therapist consultation/supervision group. Permission is obtained from the parents at this point for their adolescent to use the telephone to page the primary therapist for skills coaching as needed. Parents are told that they too can receive skills coaching when they need it by paging the multifamily group skills trainer. Also, the DBT therapist informs parents of the adolescent diary card and kindly requests that they do not ask to look at or ask their teens to share the contents of the card, since the card is intended for the therapist only. Again, the therapist attempts to preempt any intentional or inadvertent breaches of confidentiality or pressure from the parents.

Addressing issues of confidentiality is an important part of orienting the family to the DBT program. A DBT therapist typically explains the rules of confidentiality to the adolescent alone first, and then repeats them with the parents present. Although variations exist, many practitioners apply similar “rules” for breaking confidentiality: (1) if the adolescent informs DBT staff that he or she has a specific suicide plan and intent; (2) if the adolescent informs DBT staff that he or she has a specific plan and intent to harm someone else; and (3) if the adolescent suggests that any physical or sexual abuse or neglect is occurring.2 It is explained that the therapist will encourage the client to tell the parents about any of these aforementioned situations (with the possible exception of abuse/neglect if it is occurring in the household); however, the therapist will not hesitate to notify the parents if the adolescent does not.

One of the more sensitive confidentiality issues involves the issue of NSIB and whether to report that to families. Our recommendation is that DBT therapists validate parents’ concerns regarding the behavior, while at the same time saying they will not notify them of such behaviors unless they become life-threatening. The rationale for this is that adolescents may be less likely to disclose the very behaviors that bring them to treatment if they believe their parents will be notified. Many families understand this dilemma and comply with the confidentiality regarding NSIB. The exception is that if a client’s self-injury becomes increasingly dangerous and nonresponsive to DBT interventions, a therapist will break confidentiality. Other sensitive issues include substance use and sexual activity. Unless these behaviors are apparent at the outset, confidentiality about them is maintained (i.e., they are not discussed explicitly with families). Although some families probe the primary therapist for this information, we employ the same rationale for maintaining confidentiality regarding these behaviors as we do regarding NSIB. The exception also remains the same: “If I believe that your daughter [or son] is doing anything that puts her [or him] at grave risk, I will certainly let you know.”

Finally, the same commitment strategies used with the adolescent are used with the family members as needed. Typically, fewer commitment strategies are necessary to engage families in the DBT program. There are times, however, when family members exhibit insufficient commitment by suggesting that the treatment providers need to “fix” their kid without their participation, or state hopelessly that “nothing can help” the adolescents. In these cases, as well as others that are less obvious, the therapist validates the family members by suggesting how concerned and frustrated they must be to say those things. In addition, it is apparent that these problems are affecting everyone in the family. The therapist can mention recent data suggesting that those adolescents whose parents maintain a positive attitude about their treatment are more likely to have a more positive outcome (Halaby, 2004). In addition, at some point in the orientation, it behooves the therapist to mention the wealth of DBT effectiveness data for suicidal multiproblem adults and the promising pilot data with adolescents (Rathus & Miller, 2002).

When parents express their unwillingness to participate actively in the treatment, the therapist must first assess the reason. If it is not a logistical problem that needs to be solved, but rather a psychological one, the therapist may need to employ several of the commitment strategies discussed earlier. If the parents are still unwilling or unable to participate, the therapist should discuss with the consultation team how to proceed. There are times, unfortunately, despite the therapist’s and the team’s best efforts, when a family does not actively participate and an adolescent is treated alone. To date, we have no empirical data to suggest that these outcomes are necessarily any worse. Clinically, it is important for the therapist to validate the adolescent’s feelings of disappointment and rejection, while at the same time cheer-leading the teen and conveying the belief that he or she can do this treatment with the therapist’s help, even if it must be done without the family’s participation.

Anecdotally, whether a client remains in treatment beyond the first session depends largely on how effective the therapist applies the orientation and commitment strategies. Although we describe these strategies here in the early phase of treatment, most clinicians need to refer back to the majority of them, because the client’s motivation and commitment inevitably wax and wane as the treatment progresses. The next three chapters—describing individual therapy, family work, and skills training, respectively—also make use of these orientation and commitment strategies.

1The most important issue is to set a treatment time period (e.g., 16 weeks, 6 months, 1 year) for the client to commit to. The therapist and client can then either renew the agreement at the “initial” endpoint for a specified period of time, or consider referring the client to a different therapist or therapy if sufficient progress is not being made.

2Mental health professionals are mandated by state law to report any suspicion of child abuse or neglect.