CHAPTER 3

A World of Mines and Mills

Precious-Metals Mining, Industrialization, and the Nature of the Colorado Front Range

GEORGE VRTIS

One of the more striking and difficult things about seeing a mine—or studying the environmental history of mining—is trying to grasp the sheer environmental tumult involved. In the largest precious-metals mines operating today, vast open pits can reach more than a mile in width and a half mile in depth. Along the edge of the open pits are waste-rock piles that can tower thousands of feet above the surrounding landscape and can grow by hundreds of thousands of tons a day. These are the newest mountain chains to be found anywhere on earth. Depending on the mineral reduction and concentration processes used, settling ponds (or tailing dams) are also often found nearby. These water bodies can take on the dimensions of small lakes, but beyond that superficial likeness, they bear little resemblance to their naturally occurring cousins. They are routinely filled with the toxic by-products generated during mineral processing, making their water so polluted that they have been known to poison the unlucky waterfowl that land on them. Less obvious but perhaps even more complicated to discern is the wind- and water-driven dispersal of pollutants, which can carry the effects of mining far beyond any mining district. Whether we turn to images, figures, or analytical assessments, the environmental repercussions involved in contemporary precious-metals mining are not easily comprehended.1

Nor were they easily grasped when industrial mining first began sinking its roots into the mountainsides of the American West in the middle of the nineteenth century. Though historical western mining districts were different in many ways from contemporary mines, numerous visitors from the 1840s onward struggled to come to terms with what they saw. One of those visitors was James Meline. In 1866, the former New York City journalist and Union Army colonel wandered his way westward from Fort Leavenworth to Colorado and then on to New Mexico, writing thirty-six letters along the way. Six of those letters focused on Colorado, and nothing captured Meline’s imagination more than the high-country mining districts lying just west of Denver in the Front Range of the Rocky Mountains. There Meline gazed upon the ecological remnants of placer mining, noting the seemingly endless number of prospector’s holes, trenches, and mounds of debris that marked every stream. “[N]ot one stone left upon another,” Meline wrote, “not one where Nature put it.” Scanning up the surrounding mountainsides where lode mining was now the center of attention, Meline described the mountains as being “in a shockingly bad state of affairs.” “Trees and vegetation,” Meline observed, “have long since disappeared. Holes, shafts, and excavations almost obliterate the original surface.” A few days later, Meline seemed to try to sum up his views on what he had seen all across the Front Range: “Mining, from prospecting to smelting, is here, directly or indirectly, the ‘all in all’ of everyone’s existence.”2

Like Meline, environmental historians have been struggling to understand the world that mining created in Colorado and many other corners of North America and the world. As the essays in this volume and earlier work in the emerging field of mining environmental history reveal, scholars have begun unearthing the complicated stories that weave together human societies, our growing commitment to mineral-dependent cultural formats, and the way these developments interface with the natural world. From these works, we have a growing sense of the interaction among some of the key scientific and technological developments, political and economic forces, and the cultural and ecological dynamics that have been shaping our extraordinary relationship with minerals and mines since the advent of the industrial age.3

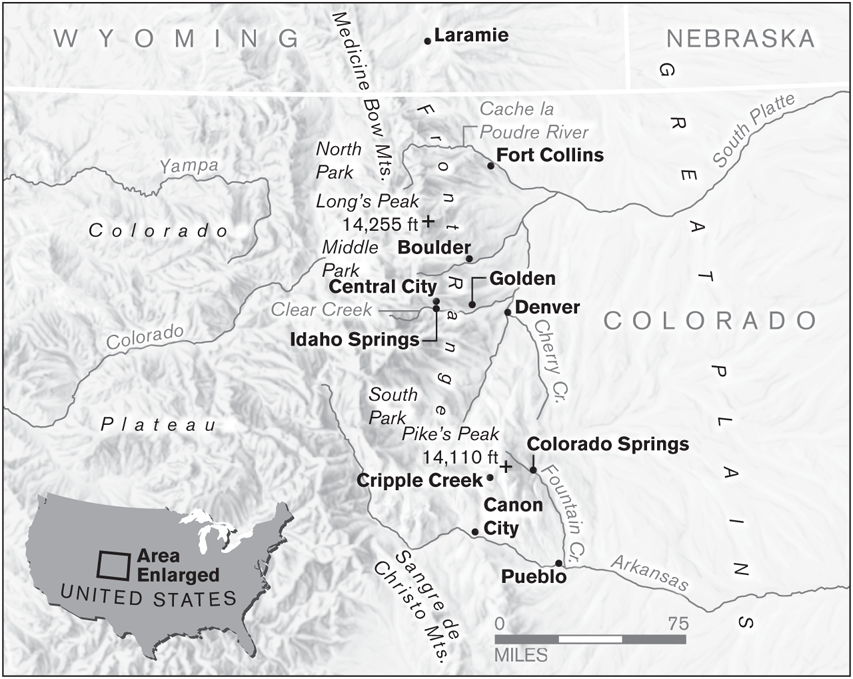

In the essay that follows, I draw on and extend aspects of the enviro-technical perspective that some scholars have recently used to analyze one of the largest and most valuable precious-metals mining regions in nineteenth-century North America, the Colorado Front Range (see figure 3.1).4 Between the mid-1860s and the end of the century, the Front Range was transformed from a peripheral frontier outpost into a modern industrial mining region in ways that dramatically recast the natural world. The often degrading environmental results, I argue, were manifestations of interlocking scientific, technological, economic, and cultural processes that were just then coming together in the form of industrialization and reshaping mining landscapes all across North America. But to see only environmental change and ruin is to miss a critical feature of this story. These same dynamics, I further suggest, began to seep into social and political consciousness in Colorado and at the national level, giving rise to an emerging eco-cultural pensiveness, to legislative and cultural developments, and to new concerns about the superabundance of the earth and scarcity that can further deepen our understanding of the American conservation movement.5

FIGURE 3.1. The Colorado Front Range, 1860–1900. Map by Jerome Cookson.

To pursue this argument, I begin with a brief assessment of Front Range precious-metals mining as it grew increasingly industrialized following the gold rush years from 1858 to 1864. Then, I turn to a detailed assessment of the enormous environmental transformations these developments set loose, using both traditional historical and scientific sources. In the chapter’s final section, I examine the way these environmental changes stirred sociopolitical concerns and reactions during the American conservation movement.

THE SHAPE OF INDUSTRIAL MINING

Beginning in 1868, mining entered a new, more complex phase of development across the Front Range as the region was pulled into the orbit of the industrializing world. Among the clearest signs of the new era were smelters, improved stamp mills, and railroads. They stood as both the symbols and the agents of the industrial world, and together signaled an important and complex break with the past. During the three decades following their nearly simultaneous introduction into the Front Range in the late 1860s and early 1870s, the spread of these and other scientific and technological developments—and the ways they interlocked with market dynamics, cultural changes, and the shift toward a new coal-powered energy regime—helped miners intensify production and environmental change on a scale never before seen in the region nor in much of North America at the time. Although the conventional view of America’s nineteenth-century industrialization is often linked to eastern factory life, workplace conflict, new technologies, and the well-worn path from New England’s textile mills to Andrew Carnegie’s sprawling Pittsburgh steelworks, industrial activity also exerted a powerful influence on the natural world, especially in the resource-rich American West.6 As smelters, stamp mills, and railroads led the Front Range down the industrial path, they helped miners fashion a radically different environment for all who followed.

The first decade of Front Range mining activity followed a pattern typical of frontier mining regions in North America. During the early boom years, from 1858 to about 1864, the easily worked surface deposits were exhausted, and the region gradually slipped into a depression as the world of the small-scale, largely independent gold seekers gave way to the much larger, more heavily capitalized corporate interests that began to control the industry after the mid-1860s. Although the passage between these two eras was marked by a massive influx of eastern and British capital, a consolidation of properties, new labor relations, the discovery of silver lodes, and a multitude of economic and social problems unleashed by both the Civil War and Great Plains Indian wars, its most important and difficult hurdle lay hidden deep within the ground.7 Often less than ninety feet below the surface of the ground, miners began encountering the Front Range’s so-called “rebellious ores.” As existing stamp-milling and other reduction processes failed to recover an economically viable percentage of the gold and silver contained in these ores, production plummeted, mines and mills sat idle, and miners began a desperate search for new reduction methods that eventually led to one of the great watersheds in the region’s nineteenth-century mining and environmental history.

In his 1870 report to Congress on the condition of the western mining industry, U.S. commissioner of mining statistics Rossiter Raymond characterized the years from 1864 to 1867 as dominated by a sort of “process-mania.” “Upon the first failure of the stamp-mills,” Raymond wrote, “people came to the conclusion that the ores must be roasted before the gold could be amalgamated. One invention for this purpose followed another; desulphurization became the Abracadabra of the new alchemists; and millions of dollars were wasted in speculations, based on the sweeping claims of perfect success put forward by deluded or deluding proprietors of patents.”8 Raymond then assessed twelve of the more familiar processes that had been or were currently being used in the Front Range. Most of them, he thought, were essentially useless and one—the Bartola process—was deemed so impracticable that he found it “difficult to reconcile the history of this invention with honesty on the part of the inventor.” The last two on the list, however, were Nathaniel Hill’s Boston and Colorado smelter and a more advanced version of the common stamp mill, both of which, Raymond observed, had already achieved some success and were busy revitalizing the industry.9

A former professor of chemistry at Brown University, Hill established the Front Range’s first successful smelter at Black Hawk—the Boston and Colorado Smelting Company—based on the best scientific knowledge available in Europe. After examining the ores around Central City and making two trips to consult with metallurgists and mining engineers at the world-renowned metallurgy centers at Swansea, Wales, and Freiburg, Germany, in the mid-1860s, Hill returned to Colorado in 1867 and began constructing a small smelting operation modeled on the famous Swansea process he observed in Wales. At the center of the process were a series of reverberatory furnaces where Hill melted the ore in order to separate the precious metals from the worthless country rock that encased it. Although the process was too expensive for treating anything but the mines’ first-class ore (the richest part of any vein), Hill’s operations were extremely effective. Estimates suggest that from the time he began operations in 1868, Hill was able to save at least 95 percent of the assay value of the ore, an extraordinary accomplishment for the day since yields prior to Hill’s smelter had dropped to as little as 10 percent of the ore’s gold content.10 As the editor of Denver’s Rocky Mountain News reflected just four years after Hill had begun operations, the Boston and Colorado Smelting Company had “done more, probably, than any one thing to re-establish confidence and build up our yield of the precious metals.”11

At the same time that Hill was organizing his smelting operations, changes in stamp-milling technologies provided a more effective and economical method for treating the great bulk of the gold ore mined: the second-class ore. After several years of experimenting with California and Nevada prototypes—each “hailed,” as Raymond put it, “as another Moses to lead us out of the wilderness”12—Front Range mill men turned sharply away from the advice of miners in other western regions and developed their own unique milling processes. In addition to lining the amalgamation tables surrounding the stamp batteries with quicksilver-coated copper plates, the real innovations of Front Range mill men focused on the production of a much more finely crushed ore. To this effect, they increased the depth of mortars, decreased the size of discharge screens, and slowed down the entire milling process. For example, compared to California stamp mills, which ran at about 90 to 105 drops per minute and crushed between 2.5 and 3 tons of ore a day, Front Range mills averaged just 30 drops per minute and crushed only about 1 ton of ore per day. The result of all these changes was promising. As the more finely crushed ore passed more slowly over the amalgamated copper plates, the loss of gold dropped substantially. From the estimated 75 to 90 percent thought lost by stamp mills in 1863, Raymond determined, the loss had been reduced to somewhere between 30 and 70 percent by 1869, while another government mining authority narrowed his estimate of the loss to between 40 and 50 percent.13

Though crucial developments, it is important to keep in mind that Hill’s Boston and Colorado Smelting Company and the improved stamp mill were only the tip of a huge industrial mining technology iceberg that took shape after 1867. Rival smelters were soon erected in nearly every mining district, and each employed increasingly well trained European and American metallurgists and mining engineers who calibrated their processes to the region’s various geological complexities. For instance, while Hill’s Swansea process worked well on the copper and iron pyrites found across much of Gilpin and lower Clear Creek Counties, it was inadequate for reducing the rich silver-bearing lead deposits found near Georgetown and Empire in upper Clear Creek County in the mid-1860s. To process these ores, miners turned to blast furnaces and still other technologies. And after 1874, miners and mill men also began relying on the scientific and technological advances developed at the Colorado School of Mines in Golden. Innovation was almost continuous. Pneumatic drills, electricity, more powerful steam engines, a better understanding of ores—over and over again, as a number of mining historians and historians of science have emphasized, advances in mining technology, metallurgy, and engineering allowed miners to overcome some difficult barrier and push the industry forward.14

Stitching together these new reduction processes and underpinning their long-term success was the nearly concurrent development of railroads. Between 1867 and 1874, six important railways began to serve the greater Front Range region. The first three created links to the East, effectively shrinking the 690 miles separating the Front Range from the nearest Missouri River valley settlements, thereby making an arduous monthlong journey into a relatively comfortable two-day train ride. In 1867, the Union Pacific reached Cheyenne, Wyoming, 106 miles north of Denver. That advent was soon followed by the completion of two other lines in 1870: the Denver Pacific, which connected Denver to the Union Pacific at Cheyenne; and the Kansas Pacific, which negotiated the Smoky Hill River valley from Kansas City to Denver. Taken together, these three lines linked the Front Range directly to the East and to national markets by rail for the first time.15

The other three railways were all principally local, narrow-gauge lines that originated in Denver and penetrated the mountains at various points. Constructed during the early 1870s, the Colorado Central, the Denver and Rio Grande, and the Denver, South Park and Pacific were engineering marvels that knitted the region together like modern highways. In addition to making transportation more feasible and reliable year-round, all of these railways combined to slash the cost of all commodities (from labor to machinery, food, and fuel) and reduced the price of moving ore around, thereby recasting the economics of mining and stimulating a reopening of shuttered mines.16

ENVIRONMENTAL UPHEAVAL: MOUNTAINS INTO MINES

As smelters, more advanced stamp mills, and railroads combined to lift the region out of the depression that had gripped it since 1864, they mediated an even more complex relationship between miners and Front Range ecosystems than the one that had emerged during the gold rush era.17 To the earlier worlds of rather simplistic placer and lode mining were added these more powerful engines of change, which accelerated the scale and rate of some environmental changes while initiating and modifying the course of others. As in the gold rush era, miners, mill men, and their supporting casts refashioned vast stretches of the mountains in their search for precious metals. Although placer mining would never again achieve a fraction of the importance it had between 1858 and 1863, small-scale operations continued to emerge from time to time and replumb waterways and destroy riparian habitat.18 Far more significant, however, was lode mining. From 1868 to the end of the century, it contributed more than 99 percent of the total value of precious-metals production, and numerous contemporary observers wrote lucid descriptions detailing its far-reaching impact on the mountains, including this succinct assessment by a visitor to the Central City region in 1873: “Everything betokens the industry of the district. The mountains are spotted with dump piles and prospect holes [. . .] The people are a mining people, earning their worldly wealth, for the most part, by delving in the bowels of the earth.”19

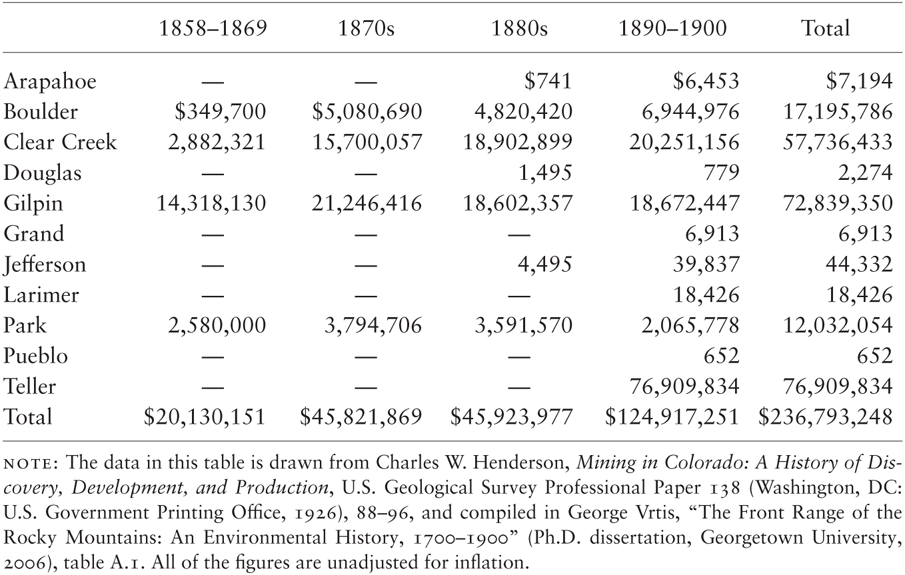

Much the same could have been written about any of the Front Range’s other major mining districts in the later nineteenth century. As the newspaperman and traveler Robert Strahorn observed in the mid-1870s, more than 60,000 mines had already been opened in the region and “the din of the quartz mill, the drill and the blast echo night and day from a thousand mountainsides and mountain depths.”20 One way of gaining a general, though clearly imperfect, sense of the mining-related environmental changes that Strahorn and others observed during the post–gold rush era is by examining the production of precious metals. Although few nineteenth-century miners would have conceived of production statements in these terms, they can be used as a basic index of environmental change. With each bar of gold or silver added to a mining company’s financial statements came a rearranging of local ecosystems, the effects radiating outward from the centers of production. In general, these changes became most pronounced around the oldest and most productive mining districts located in Gilpin, Clear Creek, and Boulder Counties; and after 1891, when a rich gold deposit was discovered in the throat of an extinct volcano in Teller County’s Cripple Creek District, that region too was transformed (see table 3.1).

TABLE 3.1 PRODUCTION OF PRECIOUS METALS (GOLD AND SILVER), COLORADO FRONT RANGE MINERAL-PRODUCING COUNTIES, BY DECADE, 1858–1900

Next to the countless mine shafts, prospect holes, and mill buildings that littered every mining district, perhaps the most readily apparent environmental change that took shape during the industrial mining era was the proliferation of increasingly vast tailing piles and debris dumps (see figure 3.2). As new mines were opened and others were pushed to greater and greater depths, the amount of material removed from subsurface shafts and tunnels and piled onto slopes and valleys increased enormously. Although the scarcity of finely detailed mining records makes it impossible to determine with precision the total amount of rock excavated, we can at least work backward and make a rough estimate. In 1875, for instance, as many of the Front Range’s most productive mines were pushing beyond 500 feet in depth,21 the region’s lode mines produced a total of $1,641,402 (about 83,109 ounces) in gold, $2,506,841 (2,021,646 ounces) in silver, and $63,745 (280,815 pounds) in copper.22 Since one-half to two-thirds of the total amount of rock excavated was gangue (the waste rock surrounding enriched veins and fissures) and even the richest first-class ores seldom assayed over 40 ounces of gold and silver and 60 pounds of copper per ton, that meant somewhere on the order of 1,968 pounds of waste rock (or 98 percent of every ton) were added to tailing piles for every ton excavated and subsequently treated by smelters, stamp mills, or other reduction processes.23 In terms of the total production figures for 1875, then, the amount of waste rock amounted to at least some 104,000 tons for just one average year in the 1870s and 1880s.24 From the 1860s onward, the shear mass of all of this material being redistributed around mountainsides and valleys destabilized numerous slopes, increasing the number of mass movements around mining districts and adding yet more sediment and debris to stream channels and aquatic habitats that had already been choked with waste rock during the gold rush era.25

FIGURE 3.2. The Silver Plume mining region, Clear Creek County, Colorado, 1870s. The discolored areas above the town are tailing piles and waste-rock dumps. Courtesy of William Henry Jackson Collection (Scan 10025699), History Colorado.

The tons of ore that were piled onto slopes and precipitated landslides had their counterpart in the warren of shafts, drifts, and tunnels that took shape beneath the mountains’ surface. In this underground world, miners altered the region’s geology and hydrology in a number of significant ways. Digging subterranean caverns removed support from the overlying strata, sometimes causing them to sag or, in extreme cases, collapse into the underlying void. Though much more common in coal-mining operations, due both to the extraction methods used and the sedimentary geology involved, ground subsidence also occurred in hard-rock mining areas.26 Mining also rearranged groundwater flows and even shifted flows between watersheds. The impressive four-mile-long Argo Tunnel (completed between 1893 and 1904) dug between Idaho Springs and the more elevated Central City, for instance, reconnected hydrological zones that had been separated for millions of years. And much as with surface water diversions, the Argo Tunnel reconfigured downstream ecological communities and habitats dependent on earlier flow regimes. Scores of other tunnels presumably produced comparable, if less well documented, hydrological and geographical changes.27

As miners constructed new geographies above and below ground, they also extended the process of deforestation begun during the gold rush era. Deeper mines meant more and heavier mine props, strengthened headframes and shafts, improved mill buildings, and an even larger consumption of wood for fuel. Below about 200 feet in depth, miners turned to wood-powered steam engines to power hoisting works, ventilation systems, and the huge pumps necessary to keep deep mines from filling up with groundwater. As the part-time historian and editor of the Central City Herald, Frank Fossett, observed, “No heavy mining work can be carried on without steam-power.”28 And, under the egalitarian prescriptions of local mining district codes and the 1872 federal mining law, each of these timber demands was multiplied thousands of times over.29 Although some miners managed to consolidate their claims into larger companies and gain economies of scale by sinking a single shaft, most sunk and timbered their own shafts and outfitted their own mines, further accelerating local deforestation. In 1872, for instance, six companies owned and operated claims on the original 800-foot-long Bobtail lode in Gilpin County, the smallest being just 33 feet, 4 inches long. The well-known Burroughs lode was similarly crowded. Its 2,347 feet were divided into seventeen distinct claims, each unleashing a seemingly insatiable demand for timber.30

Smelting operations also propelled regional deforestation. For instance, an 1876 study of the Boston and Colorado Smelting Company shows that it consumed an estimated 37.8 cords of wood in its furnaces and other reduction processes every working day. Allowing a month of downtime for repairs or weather-related problems, that amounts to an annual consumption rate of about 12,660 cords, which can be visualized as a stack of wood four feet high and four feet wide, extending the nineteen miles from Black Hawk all the way down twisting Clear Creek Canyon to the piedmont city of Golden. Obtaining that much cordwood meant clear-cutting some 160 to 210 acres of forested mountainside.31 When the timber consumption rates of all the other Front Range smelters, blast furnaces, and steam engines are considered, it is likely that miners consumed more wood for fuel during the last three decades of the nineteenth century than for any other reason.32

To these demands on the forest, however, must still be added those required by the construction of railroads. Beginning in the late 1860s, the construction of the region’s railroads required massive amounts of timber for trestles, station buildings, and most of all, for the crossties that supported iron rails. On average, every mile of standard-gauge track required around 2,400 crossties, each measuring eight feet long, seven inches on the face, and at least seven inches in depth. The narrow-gauge railways that ran into the mountains used slightly smaller crossties, but more of them, sometimes laying as many as 3,000 per mile. Constructing the 106-mile-long Denver Pacific Railway between Denver and Cheyenne, for example, required 254,000 to 260,000 crossties. On a more comprehensive scale, one study of the crosstie industry estimates that Front Range forests supplied approximately 7 million ties in its first ten years alone. Considering that hundreds of miles of track were laid in the greater Front Range region between 1868 and 1900, that ties had to be replaced every four to seven years, and that the region’s forests were also tapped to construct and maintain distant lines, it is clear that tie-cutting operations required vast numbers of mature trees.33

Not surprisingly, such enormous demands for timber leveled vast tracts of forested mountainside, creating islands of deforestation around mining districts, along waterways, and in other areas where small armies of lumbermen turned trees into crossties. In the early 1870s, for instance, a correspondent from the New York Tribune described the widespread deforestation from atop a summit overlooking Central City: “All the slopes and mountain tops were once covered with a heavy growth of pine timber, but for several miles around they have been cut away for the smelting of ores in Black Hawk and Central.”34 On his way north toward Boulder, he added a rare description of the relentless march of the lumbermen: “After five miles of travel we passed thousands of cords of wood by the roadside, which had been hauled from the mountain slopes on either hand, and we could see vast blocks taken out of the solid forest. Not many years can pass before all the timber within ten or fifteen miles of Central will be gone, and then ores must be taken to the coal at the foot of the mountains.”35 The correspondent’s prophecy was soon proven true but not without some important variations. Although the forests surrounding Central City and other major mining districts were rapidly cleared during the mid-nineteenth century, more distant forests continued to thrive, and some even managed to survive the miners’ onslaught altogether.

In the southern and central portions of the range, deforestation reached its greatest extent in the mixed ponderosa pine–Douglas fir forests that dominated the montane forest region (6,000–9,300 feet), where most mines, smelters, lumber mills, and crosstie-cutting camps were located. Since hauling wood up and down steep mountain slopes was an expensive and difficult proposition, lumbermen naturally focused their efforts on either the nearest or most easily transported sources. For the crosstie cutters, this meant harvesting stands as close as possible to the region’s major waterways. The eight-foot-long crossties weighed about 100 pounds each, making river transport the most economical method for moving them downstream to the piedmont, where oxen teams hauled them to rail lines. Until railroads reached well into the mountains in the 1870s, most crossties were moved by water and oxen teams. In some areas, such as along Clear Creek or practically anywhere below about 8,000 feet, the combined effects of the lumbermen and crosstie cutters cleared nearly all of the timber. At higher elevations, however, the dense stands of Engelmann spruce and subalpine fir that stretched across the subalpine forest region (9,300–11,400 feet) attracted far less attention. Except for those near major mining districts, these vast forests largely escaped widespread logging and today contain stands characterized by three-hundred- and four-hundred-year-old trees.36

Further north, beyond Boulder County, the pattern changed significantly. Since the northern portion of the Front Range lies outside the Colorado mineral belt and far from major mining districts, most of the logging in this region was associated with the production of crossties and thus concentrated along waterways. The heaviest logging occurred along St. Vrain Creek and the Big Thompson and Cache la Poudre Rivers, waterways that had high enough spring flows to float crossties downstream with the annual snowmelt. The crosstie drives were often immense operations that choked waterways with tens of thousands of ties. During the winter of 1868–69, for instance, more than 200,000 crossties were cut and floated down the Cache la Poudre alone. The drives continued in the Cache la Poudre and other northern watersheds until the mid-1880s, when most of the desirable trees had been cut and the industry migrated across the Continental Divide to plunder the vast forests that clothed Colorado’s western slope.37

As local deforestation ensued and railroads began to crisscross the mountains in the 1870s, Hill and other smelter men began to look more and more to relocating their operations down along the eastern piedmont where they could take advantage of railroad connections and distant ore markets, expand operations, slash labor and transportation costs, and make the long-desired switch in fuel from wood to coal. In Hill’s case, the decision to relocate finally came to a head in 1877 when Secretary of the Interior Carl Schurz persuaded the U.S. Justice Department to file suit against the Boston and Colorado Smelting Company for allegedly possessing 50,000 cords of timber illegally harvested from the public domain. Supported by a jury that upheld the public’s right to the productive resources of the public domain, Hill prevailed in the trial. Still, he must have recognized that the lawsuit was a harbinger of changing times, and it likely helped him decide to move his operations downslope to the piedmont. In 1878, after a decade of plundering the forests around Black Hawk, Hill established the sprawling new Argo plant alongside the Colorado Central’s tracks just north of Denver and turned to coal.38

Located along much of the Front Range’s eastern edge and western parks were vast coal deposits that smelter men had eyed since they first established operations in the high country. Since the cost of oxen- or horse-drawn wagon freight was generally too high to haul large amounts of coal to mountain smelters in the late 1860s, the earliest coal mines were generally small, seasonal operations that supplied local household markets in Denver, Golden, and Boulder. Beginning in the 1870s, the development of the region’s railroads and the relocation of mountain smelters changed all this. Every Colorado railway ran a line to a Front Range coalfield, and energy-intensive industries, such as smelting and iron production, increasingly began to cluster along the sides of their tracks. By the mid-1880s, the symbiotic relationship between railroads, coal, mining, and other industrial developments had led to the opening of major coal mines near Cañon City, Colorado Springs, and Boulder, as well as the establishment of some of the nineteenth-century West’s largest smelting operations in Denver and Pueblo, including the Boston and Colorado Smelting Company’s Argo plant, the Holden Smelting Company, and the Pueblo Smelting and Refining Company.39

The combined effects of the development of railways, the shift from a predominantly wood-powered to a coal-powered energy regime, and the various ways these intermingled with economic activity were part of a larger pattern then engulfing the industrializing world, and they contributed to environmental change in ways that few fully appreciated. Before the advent of the railroad and the use of fossil fuels, Front Range miners were beholden to the small network of heavily traveled dirt and plank roads and renewable energy sources (essentially muscle, biomass, and flowing water) that, like all transportation systems and energy regimes, set boundaries on resource strategies and economic development. This meant, for instance, locating stamp mills and smelters as close to mines and fuel sources as possible, since moving ore and fuel around was difficult and expensive. The railroad and coal broke these constraints, much as the wheel, horse, and sail had done for earlier human societies. Although the first locomotives burned wood, railways had begun the gradual shift toward coal in the 1830s as high-pressure, coal-burning boilers became available. By harnessing the stored photosynthesis of millions of years ago and feeding it to locomotives and smelters, Front Range miners were able to free themselves from the confines of earlier transportation and energy regimes, create ever more effective and elaborate economic linkages with the wider world, and send mining—as well as the whole process of industrialization—hurtling forward at an even more furious pace.40

The environmental ramifications of all of these developments were profound. At the most basic level, the shift from wood to coal merely transferred some of the local fuel demand from the mountain forests to the piedmont coal deposits. This had the twin effects of reducing the pressure on Front Range forests and narrowing the immediate ecological degradation caused by fuel extraction, since coal mines were much more concentrated operations than logging concerns.41 At a more complex level, the network of rails and the commitment to coal can also be seen as crucial factors in transforming the Front Range from a peripheral frontier mining society into a modern industrial one, with all the attendant and far-flung ecological consequences. In the increasingly integrated and diversified economy that emerged after the 1870s, mining entrepreneurs were able to expand their tributary spheres and tap distant ore markets from Montana to northern Mexico, while blast furnace operators working with silver-bearing lead ores could rely on high-grade coke produced in southern and western Colorado, southern Wyoming, and northern Mexico. Similarly, Front Range ores were shipped to smelters in Omaha, Chicago, and Pittsburgh, and its coal was used to power mines, smelters, and other industrial activities in Kansas City, Butte, and Salt Lake City.42 As the century wore on, the effects of mining became ever more diffused across far-distant landscapes.

While the coal mines and passing railcars signaled extensive environmental consequences, other less clearly visible ecological changes were also taking place. Throughout the nineteenth century, precious-metals mining relied on one of the most toxic heavy metals, mercury (quicksilver), to help amalgamate gold in virtually all placer- and early lode-mining devices. It was added to the riffle bars of rockers and sluices, as well as to the stamp mortars and amalgamation tables of stamp mills. Though present throughout the biosphere and in all living organisms, mercury is normally found in tiny amounts counted in parts per million (PPM) or parts per billion (PPB). For example, soils usually contain between 0.01 and 0.5 PPB; food crops may hold as much as 1.0 PPM; and human body tissue normally has between 0.2 and 0.7 PPM. In terms of aggregate amounts, the total amount of mercury commonly found in an average adult human body is just six milligrams, and the amount absorbed—through the digestive tract, skin and lungs—on a daily basis is about three micrograms.43

While the toxicity of mercury varies across species and environmental conditions, the liquid form used by nineteenth-century miners was particularly lethal since it could be volatilized and absorbed by the lungs. To cite just one well-documented example that highlights its poisonous effects, a single flask containing some 76 pounds of mercury broke open aboard the British sloop Triumph in 1810. The accident affected the entire crew, killing three, as well as all the cattle and birds aboard.44 Exactly how high mercury concentrations rose in Front Range mining districts in the nineteenth century is unknown, but they likely exceeded modern safety standards many thousandfold. According to an 1870 engineering analysis of thirty-five Gilpin County stamp mills, between 423 and 438 pounds of mercury were lost during normal operations every month. One mill alone, the Black Hawk, was reportedly losing 60 pounds a month.45 The losses, as Rossiter Raymond explained, occurred during nearly every step of the reduction process: “Every piece of wood that has come in contact with quicksilver, the canvas straining-sacks, the worn-out pan-shoes and dies, even after careful washing and breaking, the thoroughly washed and shaken quicksilver-flasks, the used up kettles and dippers, the floors, & c., all have quicksilver sticking to them; the men carry quicksilver on their boots and clothes, and it is found scattered in very small quantities outside of the mill. It goes everywhere.”46 And, Raymond might have continued, it often stayed there too. Like the sites of countless other nineteenth-century gold mines in the American West, mercury concentrations still remain highly elevated around many former Front Range mines.47

In addition to mercury, many other toxic heavy metals and hazardous substances contaminated the environment around mining districts. Stamp mill operators customarily disposed of the various concoctions of cyanide of potassium, ammonia, lime, lye, and nitric acid that they used to clean their amalgamated copper plates by dumping the leftover solution into the nearest gulch or creek.48 Smelter men pumped countless tons of sulfur dioxide, lead, arsenic, and other volatile elements into the atmosphere, coating the surrounding mountainsides with hazardous substances and, likely, sulfuric acid rain.49 In places such as Black Hawk, where Hill’s Boston and Colorado Smelting Company was located until 1877, the billowing fumes became hemmed in by Clear Creek Canyon’s high walls and gave the town a well-deserved reputation, as one visitor put it in 1873, for its “sulphurous vapors.”50 Another visitor, a correspondent for the Engineering and Mining Journal, described the smoke emanating from Hill’s smelters as filling “the atmosphere with coal dust and darkness [. . .] volumes of blackness from seventeen huge smoke stacks.”51 Although similar problems accompanied smelting operations wherever they located, they were particularly severe in places like Black Hawk that were located on the floor of a narrow canyon (see figure 3.3).

FIGURE 3.3. The Boston and Colorado Smelting Company, Gilpin County, Colorado, 1870s. Courtesy Subject File Collection, Hill Smelter (Scan 10052994), History Colorado.

Similarly pernicious and lingering environmental problems stemmed from chemical reactions taking place within the massive tailing piles and numerous shafts and tunnels that marked every mining district. Since most Front Range gold and silver deposits were locked within complex sulfides, the ongoing oxidation and weathering of these ores released varying concentrations of acidic water and toxic trace elements into surrounding watersheds. For example, as mining exposed the abundant pyrite and country rock found near Central City to water and dissolved oxygen, chemical reactions took place that left behind elevated concentrations of many hazardous metals, including arsenic, copper, cadmium, iron, lead, manganese, and zinc. Even today, nearly a century after precious-metal mining collapsed along the Front Range, the soils, groundwater, and surface water around many mining districts remain heavily polluted. Among the most seriously contaminated areas is the Clear Creek basin. The concentration of heavy metals at a number of old mining sites in the basin remains so high that they have been designated federal Superfund sites, and the cleanup continues.52

Polluted streams, soils and air, the widespread decline in forestland, and the ongoing transformation of valleys and mountainsides into mining districts further reduced wildlife populations dependent on those habitats. Already pushed to the edges of the region’s expanding mining districts and towns during the gold rush era, deer, elk, buffalo, antelope, bighorn sheep, bear, and wild turkey all but disappeared from the vast cutover regions that had been rapidly expanding since the gold rush years. Below the streams that flowed through mining districts, bottom-dwelling invertebrate communities, mollusks, crustaceans, and fish populations were also decimated and had begun to shift toward more metal- and pollution-tolerant species. By 1872, the decline in wildlife had become so great that the Colorado Territorial Assembly passed its first comprehensive wildlife protection act to establish hunting seasons and levy fines to protect many species of birds and animals. Fifteen years later, the numbers of bighorn sheep and buffalo, in particular, had plunged so sharply that the state closed the season on bighorn for eight years and on buffalo for an entire decade. For the once-numerous buffalo, the act was more of an early epitaph than anything else. The last wild buffalo in the Front Range was believed shot in South Park in 1897, leaving only place-names, such as Buffalo Peak and Buffalo Pass in North Park, to mark their former gathering places.53

Just as mining was tough on land and wild creatures, it also took a brutal toll on miners and all who lived and labored in its shadow. Mining was a dangerous occupation, and miners faced a plethora of perils in their poorly lit underground chambers. Falling rocks, collapsing shafts, earth-rattling explosions, noninsulated electrical wires, whirling machinery, pockets of groundwater, unseen holes, diseases—each of these and others disabled, debilitated, or killed countless miners.54 “The mining section,” as one Colorado resident recalled after touring the region, “is full of men with but one or no eye, and with fingers missing, while hundreds are cut down in their prime, by twos and threes, every decade.”55 If miners somehow managed to avoid all these hazards, they still had to contend with the most insidious danger of them all. The millions of microscopic silica particles produced by blasting and drilling through quartz lodes gradually accumulated in the lungs, creating tiny incisions that formed scar tissue and slowly impaired their ability to function properly. Known as silicosis or “miner’s consumption,” it frequently suffocated its victims or led to other occasionally fatal pulmonary illnesses, such as pneumonia or tuberculosis. In the early twentieth century, silicosis was eventually recognized as the leading cause of death among nineteenth-century hard-rock miners.56

Once miners left work and returned home, they, like all those who resided near mining districts, still had to contend with the smelter smoke, layers of soot, poisoned water, landslides, avalanches, floods, and other dangers peculiar to mining environments. Even a simple walk down a street, as one woman found out in Central City, could turn hazardous. According to the Daily Central City Register, a woman was seriously injured after falling ten to fifteen feet into an abandoned shaft that had been covered over and used as a cross street.57 Others were less fortunate. Patrick Ryan broke his neck and died after falling into a shaft near Central City, and a small child died after tumbling into another shaft filled with water.58 The direct effects of mining created a seemingly endless number of hazards for all who worked in or lived near the mines. As the influential editor of the Springfield (Mass.) Republican, Samuel Bowles, explained after touring the Central City mining district in 1868, the gulch is “torn with floods, and dirty with the debris of mills and mines that spread themselves over everything.”59

Writing early on in the Front Range’s industrial development, Bowles was more perceptive than he probably realized. Hill’s Boston and Colorado Smelting Company had just begun operations; new and retrofitted stamp mills were only then starting to demonstrate their worth; and the railroad era still lay two years in the future. Each of these, and the various ways they combined with other scientific, technological, and cultural developments to stimulate precious-metals production and integration into the emerging national and international marketplace, further deepened the environmental transformations that Bowles seemed to lament. In removing millions of dollars’ worth of gold and silver, miners created new landscapes and altered primary ecological processes, leaving behind a new world of gutted mountainsides, poisoned watersheds, denuded forests, and decimated wildlife populations that affected all life in the region. These two accounts are, in reality, opposite sides of the same coin and together reveal the essence of precious-metals mining in the early industrial age. Scientific, technological, capital-intensive, economically integrated, environmentally rapacious—industrial precious-metals mining was a wonder of productivity and environmental change. As Front Range mines passed from the periphery toward the core of the industrial age, the region and its creatures were profoundly transformed.

CONSERVATION-MINDED STIRRINGS

Those environmental changes were never idle developments. Over time, as Bowles and others noted, the environmental effects of precious-metals mining gave rise to anxieties and misgivings over the course of the industry’s relationship with the natural world. Many of these concerns are well known, and the powerful responses they generated in the Front Range and elsewhere in the United States have effectively made them pillars of the American conservation movement that emerged during the Progressive era. But precious-metals mining also raised important questions that do not fit neatly into the existing contours of conservationist thought in the nineteenth century and that have received too little attention from environmental historians. Minerals are fundamentally different from trees and other living things, and when miners dug into the earth in search of them, they also uncovered pathways toward a deeper and perhaps more worrisome engagement with the idea of conservation and Americans’ relationship with the natural world than has been traditionally recognized.

The historiography on the American conservation movement has some very well established grooves. Although scholars have recently pushed the chronology back into the eighteenth century and expanded the scope beyond its traditional figures and concerns, the movement’s major benchmarks continue to revolve around a series of environmental threats that gathered national attention between about 1890 and 1920: dwindling forests and wildlife, polluted cities and unhealthy workplaces, wasteful extraction methods and production practices, and the decline of wilderness and the general cornering-up of nature. In response to these developments, early conservationists—such as the diplomat and philologist George Perkins Marsh; the first chief of the U.S. Forest Service, Gifford Pinchot; President Theodore Roosevelt; and the preservationist and founder of the Sierra Club, John Muir—pushed for the creation of the nation’s first national forests, first wildlife refuges, and first national parks, as well as new game protection laws, new sanitation regulations, and new and expansive public health initiatives. As scholars have shown, many of these foundational features of the American conservation movement were influenced by western precious-metals mining and the social and political responses that followed.60

In the Front Range, for instance, the decline in forests led concerned members of Colorado’s state constitutional convention in 1876 to push successfully for Article 18, which pledged the General Assembly to “enact laws in order to prevent the destruction of, and to keep in good preservation, the forests upon the lands of the state.” This was followed in the mid-1880s by the establishment of the Colorado State Forestry Association (1884) and the Office of the State Forest Commissioner (1885), which sought to prevent forest fires, preserve forests, and encourage silviculture. These initiatives eventually mingled with the concerns of others across the country and helped propel passage of the 1891 Forest Reserve Act at the national level, creating the National Forest Reserve system. Within two years of its passage, President Benjamin Harrison had established fifteen forest reserves, including three in the Front Range that amounted to just over 1 million acres.61

Similarly, the billowing fumes, airborne silica particles, diseases, and other hazardous environmental effects of precious-metals mining in the Front Range led to the formation of local benevolent associations and fraternal lodges to care for miners and their families who had been injured, fallen sick, or been killed. Miners also formed labor unions to carry forward the work of the benevolent associations and fraternal lodges, and to press mine owners and the Colorado legislature for mine safety and mine inspection laws, the eight-hour workday, a workmen’s compensation system, and other initiatives. The first hard-rock mining union formed anywhere in the American West was organized in the Front Range at Central City in 1863. From these beginnings, miners’ unions became a regular feature of Colorado’s mining industry for the rest of the century. By 1900, at least half of Colorado’s miners are thought to have joined the Western Federation of Miners, arguably the most powerful miners’ union in the United States at the time.62

The environmental transformation of the Front Range also played a role in the establishment of the region’s first national park, Rocky Mountain National Park. In 1915, Congress set aside 231,000 acres of land along the western edge of the Front Range, extending from Estes Park west to the Continental Divide. As with other national parks, the campaign for Rocky Mountain reflected concerns about the beauty and wonder of nature that have long been associated nationally with John Muir, and in Colorado with one of Muir’s chief disciples, the naturalist Enos Mills. In 1909, when Mills was just beginning the campaign that would lead to the establishment of Rocky Mountain, he worried aloud about what was being lost: “Extensive areas of primeval forest have been misused and ruined; the once numerous big game has been hunted almost out of existence, the birds are falling, the wild flowers vanishing, and the picturesque beaver, except where protected, are almost gone.” In 1915, those imperiled landscapes were set aside by congress “for recreation purposes by the public and for the preservation of the natural conditions and scenic beauty thereof.”63

Each of these responses to the Front Range’s changing environment—the creation of forest reserves, the establishment of benevolent associations and unions, the push for mine safety laws, and the establishment of Rocky Mountain National Park—ties neatly into the historiography of the American conservation movement. But there is also evidence to suggest that some public officials carried their concerns about mining and the environmental changes it precipitated beyond the conservation movement’s well-known focal points. In 1868, for instance, the nation’s first U.S. commissioner of mines and mining statistics, J. Ross Browne, included the following passage in his report to Congress on the condition of the western mining industry:

No country in the world can show such wasteful systems of mining as prevail in ours. At a moderate calculation, there has been an unnecessary loss of precious metals since the discovery of our mines of more than $300,000,000, scarcely a fraction of which can ever be recovered. This is a serious consideration. The question arises whether it is not the duty of government to prevent, as far as may be consistent with individual rights, this waste of a common heritage, in which not only ourselves but our posterity are interested. The miner has a right to the product of his labor, but has he a right to deprive others of the benefits to be derived from the treasures of the earth, placed there for the common good?64

Although the thrust of Browne’s comments was clearly directed at increasing mining and metallurgical efficiencies in order to reduce mineral losses, his views are unmistakably tinged with notions of restraint, equity, or what we might today call sustainability. While Browne did not try to answer the far-reaching questions he posed, they stand like signposts to the age, pointing the way toward a deeper engagement with the heart of a conservation ideology that was just beginning to be pieced together in various corners of the country.

Like Browne, his successor as U.S. commissioner of mines and mining statistics and one of the nation’s leading authorities on mining, Rossiter Raymond, also grappled with weighty questions not customarily seen as part of the conservation movement. In 1885, for instance, Raymond published an ambitious article on the history of mining law. Reaching from the Phoenicians, Greeks, and Romans to modern European states, Mexico, Canada, and the United States, Raymond discussed mining rights, patents, and royalty systems. But the concern that seems to animate Raymond’s inquiry is what he called “the unique character of the industry itself.” As he explained, “The deterioration of the soils through ignorant or reckless agriculture may be cured in time by wiser methods; forests wantonly destroyed may be replanted; fishing grounds left to themselves or restocked artificially may recover their prolific abundance of supply, but coal, iron, copper, lead, petroleum, gold, and silver will not come again within the history of the human race into the places from which they have been extracted. A waste of them is a waste forever.” Within the same paragraph, Raymond underscored these ideas, characterizing the mining of minerals “as constantly tending towards a permanent exhaustion of the natural resources of the land.”65

Raymond’s and Browne’s concerns about mineral exhaustion and a sense of environmental limits were unusual for the age. Throughout much of the nineteenth century, American attitudes toward mineral stocks were far more ebullient, far closer to the one expressed in 1869 by the geologist Ferdinand Hayden, whose famous surveys of the American West included the Front Range. Hayden described the mines around South Clear Creek as “very rich and practically inexhaustible.”66 His sense of the region’s seemingly endless mineral abundance drew on a particular view of mineral veins that was ubiquitous across many levels of society in the 1860s and well into the later nineteenth century. It was evident in the views of geologists and miners, as well as in those of boosters and speculators. As a professor of geology at Brown University, George Chase, put it:

The universal experience in Colorado is that the lodes increase in richness as they are followed downwards. In this respect they are remarkably distinguished from those of Australia and most other gold districts, where the richest ore is found in the first hundred feet from the surface. The deeper workings are less productive; and at length become unprofitable, and are abandoned. The apparent exception to the general law governing gold-bearing lodes—an exception in favor of those in Colorado—adds greatly to their desirableness and value.67

Others echoed Chase’s position. Writing for an unspecified mining committee report in 1864, the mining attorney William Rockwell described Colorado’s “true fissure veins [as] having no termination downwards attainable by human ingenuity.” In fact, Rockwell summed up, “no well-developed and defined vein has ever been found entirely terminating in depth.”68 Another mining attorney, J. Weatherbee Jr., characterized Colorado’s mineral veins similarly, noting in an 1863 brief on the Colorado Territory that “if the vein pays at the blossom, it will pay better as you descend.” And, as if to ward off unease, Weatherbee went on to state that even if a vein reached a cap, “it is sure to open again, and the richer for it, if your courage holds.”69

And yet, even as such hopeful views of Colorado’s veins were carrying forward an older cornucopian vision of nature, experiences in the Front Range and elsewhere in the American West were beginning to tilt opinion in Raymond’s and Browne’s direction. As vein after vein pinched out into cap, and as mine after mine exhausted its paying ore and shuttered its tunnels, anxieties like Raymond’s and Browne’s were being levered into new conceptual, social, and political consciousness.70 We see this most clearly in 1908, when President Theodore Roosevelt invited all of the state governors to the White House to discuss the idea of conservation. The proceedings of that conference and the Report of the National Conservation Commission that followed are filled with warnings about limited and declining stocks of minerals, and about how wasteful mining and production practices threaten America’s industrial prosperity.71 Although Congress failed to maintain the National Conservation Commission and its work on coordinating and assessing resource exploitation for the country, the commission—and particularly its focus on minerals—raised striking new concerns about the earth’s superabundance and the depths that mining pushed those concerns during the Progressive era.72

CONCLUSION

When James Meline wandered into the Front Range in 1866, he found himself in the midst of multiple revolutions. The industrialization of mining, the dramatic evolution of science and technology, the rise of new energy sources, the expansion and integration of economic markets—all of these and other developments were just then becoming entangled in the Front Range and beginning to recast the world around him in fundamental ways. As these processes unfolded, they also gave rise to an emerging eco-cultural pensiveness and to new understandings about mineral deposits, which expressed themselves in the form of environmental and cultural misgivings, anxieties, and eventually, legislative and cultural measures that looked to counter some of the most destructive trends. From this viewpoint, the history of the American conservation movement takes on new meaning. Not only did western precious-metals mining contribute to well-known features of the conservation movement such as deforestation and the creation of national parks, but it also seeded larger questions—stubborn, difficult questions that merit further research—about mineral exhaustion, scarcity, progress, and the superabundance of the earth in ways that forests and other renewable resources never did, or perhaps could. As we think our way through this past, widening our understanding of the scope of the conservation movement and blurring the sharp lines that once separated earlier ideas about conservation from our own today, we might just find some fresh new insights and a historical forum for thinking about our current environmental circumstances and the challenges they pose.

NOTES

1. For two recent articles on how environmental concerns tie up with contemporary gold mining, see Edwin Dobb, “Alaska’s Choice: Salmon or Gold,” National Geographic 218:6 (December 2010): 100–125; and Brook Larmer, “The Real Price of Gold,” National Geographic 215:1 (January 2009): 34–61.

2. James F. Meline, Two Thousand Miles on Horseback, Santa Fe and Back: A Summer Tour through Kansas, Nebraska, Colorado, and New Mexico in the Year 1866 (New York: Hurd and Houghton, 1867), 63–65.

3. Foundational works in this area include Thomas G. Andrews, Killing for Coal: America’s Deadliest Labor War (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2008); Andrew C. Isenberg, Mining California: An Ecological History (New York: Hill and Wang, 2005); Kathryn Morse, The Nature of Gold: An Environmental History of the Klondike Gold Rush (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2003); and Duane Smith, Mining America: The Industry and the Environment, 1800–1980 (Niwot: University Press of Colorado, 1993).

4. On the use of enviro-technical perspectives in environmental history, see the pathbreaking work done by Timothy J. LeCain, in Mass Destruction: The Men and Giant Mines That Wired America and Scarred the Planet (New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, 2009), and the collected essays in Susan R. Schrepfer and Philip Scranton, eds., Industrializing Organisms: Introducing Evolutionary History (New York: Routledge, 2004). Though not consciously framed as enviro-technical, also very useful is Paul R. Josephson, Industrialized Nature: Brute Force Technology and the Transformation of the Natural World (Washington, DC: Island Press/Shearwater Books, 2002). In addition, for deeper theoretical considerations, see Rosalind Williams, Notes on the Underground: An Essay on Technology, Society, and the Imagination, new ed. (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2008); Bruno Latour, Science in Action: How to Follow Scientists and Engineers through Society (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1988); and the now-classic work of Lewis Mumford, Technics and Civilization (1934; reprint, New York: Harcourt Brace, 1963).

5. For recent scholarship that focuses on the early history of the American conservation movement, see Richard W. Judd, The Untilled Garden: Natural History and the Spirit of Conservation, 1740–1840 (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2009); Aaron Sachs, The Humboldt Current: Nineteenth-Century Exploration and the Roots of American Environmentalism (New York: Penguin Books, 2006); and Richard W. Judd, Common Lands, Common People: The Origins of Conservation in Northern New England (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1997). On the relationship between developments in the nineteenth-century American West and the conservation movement, see, for instance, Stephen Fox, The American Conservation Movement: John Muir and His Legacy (Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1981); Samuel P. Hays, Conservation and the Gospel of Efficiency: The Progressive Conservation Movement, 1890–1920 (1959; reprint, Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press, 1999); G. Michael McCarthy, Hour of Trial: The Conservation Conflict in Colorado and the West, 1891–1907 (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1977); and Ronald C. Brown, Hard-Rock Miners: The Intermountain West, 1860–1920 (College Station: Texas A&M University Press, 1979).

6. For recent works that look at industrialization and environmental change within the confines of the nineteenth-century American West, see David Igler, “Engineering the Elephant: Industrialism and the Environment in the Greater West,” in A Companion to the American West, ed. William Deverell (Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell, 2004), 93–111; David Igler, Industrial Cowboys: Miller & Lux and the Transformation of the Far West, 1850–1920 (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2001); David Igler, “The Industrial Far West: Region and Nation in the Late Nineteenth Century,” Pacific Historical Review 69 (May 2000): 159–92; and Steven Stoll, The Fruits of Natural Advantage: Making the Industrial Countryside in California (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1998).

7. For a comparative examination of western mining regions, see Rodman Wilson Paul and Elliott West, Mining Frontiers of the Far West, 1848–1880, revised and expanded ed. (Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 2001). For the relationship among eastern and British financiers, economic conditions, and Front Range mining developments in the nineteenth century, see Joseph E. King, A Mine to Make a Mine: Financing the Colorado Mining Industry, 1859–1902 (College Station: Texas A&M University Press, 1977), and Clark C. Spence, British Investments and the American Mining Frontier, 1860–1901 (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1958).

8. Rossiter W. Raymond, Statistics of Mines and Mining in the States and Territories West of the Rocky Mountains, U.S. Department of the Treasury (Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1870), 347–48. Though imprecisely labeled, these annual reports to Congress also cover developments in the Rockies. Raymond issued eight annual reports in this series (1869–1877); all but the first share the same title and are hereafter cited by annual report year.

9. Raymond, Statistics of Mines and Mining in the States and Territories West of the Rocky Mountains (1870), 356–65. See also James W. Taylor, Report of James W. Taylor on the Mineral Resources of the United States East of the Rocky Mountains, U.S. Department of the Treasury (Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1868), 21.

10. James D. Hague and Clarence King, Mining Industry, by James D. Hague, with Geological Contributions by Clarence King; Submitted to the Chief of Engineers and Published by Order of the Secretary of War Under Authority of Congress, in Report of the Geological Exploration of the Fortieth Parallel (Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1870), 3:577–88; Ovando J. Hollister, The Mines of Colorado (Springfield, MA: Samuel Bowles and Co., 1867), 134; Frank Fossett, Colorado: Its Gold and Silver Mines, Farms and Stock Ranges, and Health and Pleasure Resorts (1879; reprint, New York: Arno Press, 1973), 143, 226; Henry Dudley Teetor, “Refining and Smelting in Colorado: Prof. Richard Pearce, F.G.S., Manager of the Boston and Colorado Smelting Works,” Magazine of Western History 11:3 (January 1890): 278–82. For secondary works that treat the significance of Nathaniel Hill and the Boston and Colorado Smelting Company, see James E. Fell, Ores to Metals: The Rocky Mountain Smelting Industry (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1979), 11–38; Jesse D. Hale, “The First Successful Smelter in Colorado,” Colorado Magazine 13:5 (September 1936): 161–67; C.H. Hanington, “Smelting in Colorado,” Colorado Magazine 23:2 (March 1946): 80–84; and Charles W. Henderson, Mining in Colorado: A History of Discovery, Development, and Production, U.S. Geological Survey Professional Paper 138 (Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1926), 9, 27–32, 36–40.

11. Rocky Mountain News, 27 November 1872.

12. Raymond, Statistics of Mines and Mining in the States and Territories West of the Rocky Mountains (1870), 365.

13. Ibid., 364–65; Raymond, Statistics of Mines and Mining in the States and Territories West of the Rocky Mountains (1872), 339–73; Hague and King, Mining Industry, 3:548–73; A.N. Rogers, “The Mines and Mills of Gilpin County,” Transactions of the American Institute of Mining Engineers 11 (1883): 29–55; T.A. Rickard, “Limitations of the Gold Stamp Mill,” Transactions of the American Institute of Mining Engineers 23 (1893): 137–47; Edson S. Bastin and James M. Hill, Economic Geology of Gilpin County and Adjacent Parts of Clear Creek and Boulder Counties, Colorado, U.S. Geological Survey Professional Paper 94 (Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1917), 154–56; Samuel Cushman and J.P. Waterman, The Gold Mines of Gilpin County, Colorado: Historical, Descriptive and Statistical (Central City, CO: Register Steam Printing House, 1876), 99–102.

14. The evolution and spread of the science and technology of mining and mineral reduction processes are nicely covered in Paul and West, Mining Frontiers of the Far West, 123–34, 270–77; Fell, Ores to Metals; Crane, Gold and Silver, 496–552; Thomas Tonge, “Smelting Gold and Silver Ores in Colorado: The Development of the Industry and Its Effects on the Mining Business,” Mines and Minerals 19:3 (October 1898): 97–100; and Clark C. Spence, Mining Engineers and the American West: The Lace-Boot Brigade, 1849–1933 (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1970). On developments at the Colorado School of Mines, see Kathleen H. Ochs, “The Rise of American Mining Engineers: A Case Study of the Colorado School of Mines,” Technology and Culture 33:2 (April 1992): 278–301. Firsthand observations and illustrations of many of these processes (including Brückner’s revolving cylinders and the Washoe pan process), as well as the intellectual advances that propelled them, can be found in Raymond, Statistics of Mines and Mining in the States and Territories West of the Rocky Mountains (1870), parts 4–5; Raymond, Statistics of Mines and Mining in the States and Territories West of the Rocky Mountains (1874), 407–98; Hague and King, Mining Industry, 3:547–88, 606–16; and Richard Pearce, “Progress of Metallurgical Science in the West,” Transactions of the American Institute of Mining Engineers 18 (1889): 55–72. On Front Range ore types, see Bastin and Hill, Economic Geology of Gilpin County and Adjacent Parts of Clear Creek and Boulder Counties; T.S. Lovering and E.N. Goddard, Geology and Ore Deposits of the Front Range, Colorado, U.S. Geological Survey Professional Paper 223 (Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1950); and Waldemar Lindgren and Frederick Leslie Ransome, Geology and Gold Deposits of the Cripple Creek District, Colorado, U.S. Geological Survey Professional Paper 54 (Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1906).

15. On the importance of railroads in shaping western development, see Richard White, Railroaded: The Transcontinentals and the Making of Modern America (New York: W.W. Norton, 2011); Carlos A. Schwantes and James P. Ronda, The West the Railroads Made (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2008); William Cronon, Nature’s Metropolis: Chicago and the Great West (New York: W.W. Norton, 1991), 63–81; and Duane A. Smith, Rocky Mountain West: Colorado, Wyoming, and Montana, 1859–1915 (Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 1992), 54, 98–120.

16. The development of Colorado’s early railway networks is covered in E.O. Davis, The First Five Years of the Railroad Era in Colorado (Golden, CO: Sage Books, 1948); Tivis E. Wilkens, Colorado Railroads: Chronological Development (Boulder, CO: Pruett, 1974); R.A. LeMassena, Colorado’s Mountain Railroads (Golden, CO: Smoking Stack Press, 1968); Kenneth Jessen, Railroads of Northern Colorado (Boulder, CO: Pruett, 1982); and Robert G. Athearn, Rebel of the Rockies: A History of the Denver and Rio Grande Western Railroad (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1962). For the precise routes traveled by these lines in Colorado, see Kenneth A. Erickson and Albert W. Smith, Atlas of Colorado (Boulder: Colorado Associated University Press, 1985), 28–29.

17. On the environmental history of Colorado during the gold rush years, see George Vrtis, “Gold Rush Ecology: The Colorado Experience,” Journal of the West 49:2 (Spring 2010): 23–31.

18. For instance, see F.V. Hayden, Third Annual Report of the United States Geological Survey of the Territories, Embracing Colorado and New Mexico (Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1869), 225; F.V. Hayden, Ninth Annual Report of the United States Geological and Geographical Survey of the Territories, Embracing Colorado and Parts of Adjacent Territories; Being a Report of Progress of the Exploration for the Year 1875 (Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1877), 425; Raymond, Statistics of Mines and Mining in the States and Territories West of the Rocky Mountains (1873), 296; and Raymond, Statistics of Mines and Mining in the States and Territories West of the Rocky Mountains (1874), 298–99.

19. On the relative contributions of placer and lode mining, see the detailed calculations in George Vrtis, “The Front Range of the Rocky Mountains: An Environmental History, 1700–1900” (Ph.D. dissertation, Georgetown University, 2006), table A.1. For the visitor quotation, see Charles Harrington, Summering in Colorado (Denver: Richards and Co., 1874), 31–32.

20. Robert E. Strahorn, To the Rockies and Beyond; or, A Summer on the Union Pacific Railroad and Branches: Saunterings in the Popular Health, Pleasure, and Hunting Resorts of Nebraska, Dakota, Wyoming, Colorado, Utah, Idaho, Oregon, Washington and Montana, 2nd ed. (Omaha: New West Publishing Co., 1879), 34. See also Fossett, Colorado, 58, 62, 386.

21. Cushman and Waterman, The Gold Mines of Gilpin County, Colorado, 43–98; Raymond, Statistics of Mines and Mining in the States and Territories West of the Rocky Mountains (1877), 290–321, esp. 291.

22. For 1875 production figures, see Vrtis, “The Front Range of the Rocky Mountains,” table A.1. For the conversion of the total value of gold into ounces, I have used $19.75 per ounce (the official price of gold paid by the U.S. Mint throughout the later nineteenth century).

23. Raymond, Statistics of Mines and Mining in the States and Territories West of the Rocky Mountains (1872), 347; and Bastin and Hill, Economic Geology of Gilpin County, 109–20.

24. This is a conservative estimate of the amount of waste rock produced by milling processes since (1) it uses the minimum value of one-half for the amount of waste rock produced from initial sorting operations, and (2) it assumes that all of the precious metals were recovered from a single type of ore, which occurred, but was certainly not the norm for the region.

25. Ellen E. Wohl, Virtual Rivers: Lessons from the Mountain Rivers of the Colorado Front Range (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2001), 78–81; Raymond, Statistics of Mines and Mining in the States and Territories West of the Rocky Mountains (1877), 291–92.

26. Vicki Cowart, “When the Ground Lets You Down: Ground Subsidence and Settlement Hazards in Colorado,” Rock Talk (Colorado Geological Survey) 4:4 (October 2001): 1–12; Jeffrey L. Hynes, ed., Proceedings of the 1985 Conference on Coal Mine Subsidence in the Rocky Mountain Region, Colorado Geological Society Special Publication 31 (Denver: Colorado Geological Society, 1986).

27. The Argo and other tunnels are discussed in Bastin and Hill, Economic Geology of Gilpin County, 303–6 (Argo), 177–367 (other tunnels). On the downstream effects of water diversion projects, see Wohl, Virtual Rivers, 72, 117–25.

28. Fossett, Colorado, 205, quote on 290.

29. On the Mining Law of 1872, see Gordon Morris Bakken, The Mining Law of 1872: Past, Present, and Prospects (Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 2008).

30. Raymond, Statistics of Mines and Mining in the States and Territories West of the Rocky Mountains (1873), 288.

31. The details used in determining these timber consumption rates are drawn from Thomas Egleston, “Boston and Colorado Smelting Works,” Transactions of the American Institute of Mining Engineers 4 (1876): 276–98. The cords per acre of forested mountainside conversion factor of 60 to 80 used here is based on Raymond, Statistics of Mines and Mining in the States and Territories West of the Rocky Mountains (1877), 330.

32. For instance, according to Raymond’s 1874 annual report, the number of smelters and blast furnaces operating in the Front Range amounted to fifteen. He does not provide a listing for stamp mills, but unlike smelting enterprises, which tended to be organized as independent companies, most of the hundreds of mines also had their own stamp-milling operations. See Raymond, Statistics of Mines and Mining in the States and Territories West of the Rocky Mountains (1875), 388. For an analysis of the timber consumption rates of steam engines operating in Gilpin County in 1871, see “Report on the Committee on Statistics,” Daily Central City Register, 7 May 1871. Based on this report, the total number of steam engines then in use required 170 cords of wood per day to operate, an amount four times greater than the daily amount used by the Boston and Colorado Smelter.

33. William H. Wroten Jr., “The Railroad Tie Industry in the Central Rocky Mountain Region, 1867–1900” (Ph.D. dissertation, University of Colorado at Boulder, 1956), 4, 65–156, esp. 124.

34. New York Tribune correspondent quoted in Raymond, Statistics of Mines and Mining in the States and Territories West of the Rocky Mountains (1872), 325. For similar observations, see F.V. Hayden, Annual Report of the United States Geological and Geographical Survey of the Territories, Embracing Colorado; Being a Report of Progress of the Exploration for the Year 1873 (Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1874), 280; Daily Central City Register, 10 August 1874; and George A. Crofutt, Crofutt’s Grip-Sack Guide of Colorado: A Complete Encyclopedia of the State (Omaha: Overland Publishing Co., 1881), 42.

35. New York Tribune correspondent quoted in Raymond, Statistics of Mines and Mining in the States and Territories West of the Rocky Mountains (1872), 325.

36. Some of the best comprehensive data on the extent of nineteenth-century deforestation comes from modern scientific studies. The following studies of Front Range forest dynamics include quantitative and repeat photographic data on stand characteristics, which can, by working backward, provide an indication of the composition of earlier time periods: John W. Marr, Ecosystems of the East Slope of the Front Range in Colorado, University of Colorado Studies Series in Biology No. 8 (Boulder: University of Colorado Press, 1967), esp. 25–75; Robert K. Peet, “Forest Vegetation of the Colorado Front Range: Composition and Dynamics,” Vegetation 45 (1981): 8–9, 37–75; Thomas T. Veblen and Diane C. Lorenz, The Colorado Front Range: A Century of Ecological Change (Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press, 1991), esp. 18–9, 173–76; and Thomas T. Veblen and Diane C. Lorenz, “Anthropogenic Disturbance and Recovery Patterns in Montane Forests, Colorado Front Range,” Physical Geography 7:1 (1986): 1–22. On tie-cutting operations, see Wroten, “The Railroad Tie Industry in the Central Rocky Mountain Region,” 65–156, 264–87. For firsthand observations on the extent of the regional deforestation, see Fossett, Colorado, 240, 284; Strahorn, To the Rockies and Beyond, 58; John G. Jack, Pikes Peak, Plum Creek and South Platte Forest Reserves, Showing Density of Forests, U.S. Geological Survey Twentieth Annual Report, part 5 (Washington, DC: U.S. Geological Survey, 1898), plate 8; and, more generally, Enos A. Mills and W.G.M. Stone, The Forests and Exotic Trees of Colorado (Denver: Colorado State Forestry Association, 1905), 5–17.