CHAPTER 11

Iron Mines, Toxicity, and Indigenous Communities in the Lake Superior Basin

NANCY LANGSTON

This chapter explores toxics mobilized by iron mining in the Lake Superior basin, a region shared between the United States and Canada that is currently witnessing a major mining boom (figure 11.1). Toxics from iron mines have moved from their sites of production and consumption into much broader and dispersed spaces. As they flow into water, they bioaccumulate in fish and eventually make their way into the people who eat those fish. These contaminants have permeated global ecosystems, crossing international boundaries to contaminate people far from initial sources of production and consumption. Their toxic residues not only complicate political boundaries but also confuse temporal distinctions, for their legacies persist long after they have been banned. Moreover, the risks of exposure to these chemicals is rarely distributed in a human population equitably.

FIGURE 11.1. Extent of mining exploration and activity around Lake Superior, 2016. Map by Bill Nelson, modified from a base map created by Great Lakes Indian Fish and Wildlife Commission.

In 2011, the iron ore–mining company Gogebic Taconite (GTAC) proposed the world’s largest open-pit mine in the world just upstream from the reservation of the Bad River Band of the Lake Superior Tribe of Chippewa. While the mine would have been sited on one side of a legal boundary, the waters would have flowed across those boundaries to contaminate water, fish, and indigenous communities downstream (figure 11.2).1

FIGURE 11.2. Location of the proposed Gogebic Taconite mine in relation to the Bad River Reservation, Lake Superior watershed. Map by Bill Nelson.

If permits had been approved, the GTAC mine would have been located within ceded territories where the tribes retained hunting, fishing, gathering, and co-management rights when they signed treaties in the nineteenth century enabling white settlement (figure 11.3). Bad River Band members point out that it is no accident that the proposed mine site was within their watershed. As environmental justice scholars argue, environmental exposures vary in their spatial distribution, and social inequalities influence vulnerability. Tribal members have often borne the greatest burden from the toxic wastes fostered by past mining projects, but they have rarely had much decision-making power in the planning process.2

FIGURE 11.3. Map of the ceded territories of the Lake Superior Ojibwe. Map by Bill Nelson, modified from a base map created by Great Lakes Indian Fish and Wildlife Commission.

The Bad River runs through the potential mine site before entering the 16,000-acre Kakagon–Bad River Sloughs—the largest undeveloped wetland complex in the upper Great Lakes. In 2012, this was designated as a Ramsar Site, recognizing it as a wetland of international importance. The Ramsar Convention on Wetlands noted that “as the only remaining extensive coastal wild rice bed in the Great Lakes region, it is critical to ensuring the genetic diversity of Lake Superior wild rice.”3 The sloughs make up 40 percent of the remaining wetlands on Lake Superior’s coast, and they contain the largest natural wild rice beds in the entire world (figure 11.4).

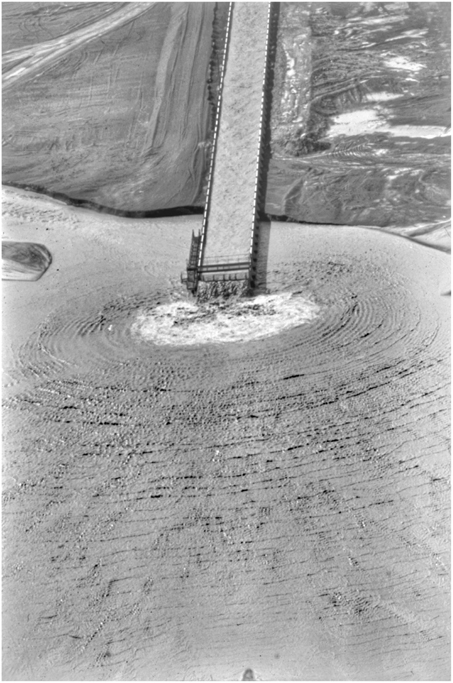

FIGURE 11.4. Taconite launder. The conveyor discharges taconite tailing residue into Lake Superior at Reserve Mining Company’s taconite plant in Silver Bay, Minnesota, June 1973. Photograph by Donald Emmerich, U.S. National Archives and Records Administration (Record 3045077).

For members of the Bad River Band, these wild rice beds are central to their identity and important to their economy. When the Anishinaabe migrated westward from the St. Lawrence River valley, the ancestors of the Bad River Band chose to make their homes along the Kakagon Sloughs because the wild rice beds they found there had figured significantly in their visions. In the sloughs, they found wild rice, or manoomin, “the food that grows on water,” which they continue to see as a “sacred gift from the Creator.”4 The wild rice became a major portion of their subsistence, and fisheries supported by the sloughs became equally important for subsistence and for economic development. Wild rice is extremely sensitive to sulfates in the watershed that may become mobilized by taconite mines. Band members argued that stopping the mine was essential for their survival, not just to ensure thriving wild rice beds and fisheries but also to sustain the connection with the past that is at the core of their cultural identity.

In contrast, many Euro-American residents of nearby communities such as Hurley, Wisconsin, argued that the proposed mine was the only thing that could rescue them from the economic devastation that followed the closure of local hematite iron mines in the 1960s. Hurley lies just outside the subwatershed that would have been affected by the proposed mine, so the town would not have been directly influenced by any water quality issues presented by the mine. Denying permits for the proposed mine, Hurley residents argued, would have amounted to a form of economic suicide.

As John Sandlos and Arn Keeling have argued for Pine Point Canada, “Complex and contested meanings or place and community” are common at mining sites. “While regarded by ‘outsiders’ as brutal, degraded or even toxic,” the authors observe, “former mining landscapes may be touchstones of community identity and memory and provide both material and cultural resources for economic recovery or even political resistance.”5 This is certainly true for iron mines in the Lake Superior basin. Different communities within the basin have quite different interpretations of that mining past, and these views about the past help to shape their perspectives on current mining proposals.

IRON-MINING HISTORIES IN THE BASIN

While many Euro-American locals see iron mining as part of their past, the differences between types of iron ore are typically obscured in the retellings of history. Yet these differences are critical for both environmental and social consequences. Briefly, iron ore in the Lake Superior basin falls into two broad types: direct-shipping ore (generally hematite) that contains quite high concentrations of iron, and low-grade ore (generally taconite) that needs to be concentrated or processed before shipping. Historically, hematite, at 60–70 percent iron, needed little processing before shipping, required much labor to produce, and in Wisconsin was mined underground. Taconite, in contrast, was more abundant in the Lake Superior basin but much less concentrated (typically about 25% iron in an ore body). Mining taconite requires enormous open pits, extensive technological and financial investments, vast quantities of water, and minimal human labor.

The Penokee Range lies in what is now northern Wisconsin; across the border in the Upper Peninsula of Michigan, the same range is named the Gogebic Range; when referring to the entire range, this essay uses the term Penokee-Gogebic Range. Once the center of a thriving—but short-lived—hematite-mining economy followed by clear-cutting, the region’s forests have now grown back, enough so that one environmental group can write that the Penokees “form the heart of one of the most isolated, pristine and scenic portions of the state.” The first phase of the proposed GTAC taconite mine would have created a pit 5 miles long and 1,000 feet deep. Eventually, plans called for 22 miles along the ridge of the Penokees to be carved off. The proposed techniques bore little resemblance to the deep-shaft mining for hematite that was the basis of the region’s mining history. Rather, this would have become the first “mountaintop removal” mine in the upper Great Lakes region. As one anti-mining activist writes: “Gogebic Taconite (GTac) has grandiose plans for the Penokee mountains: To blow them to smithereens with a series of 5.5 million–pound explosives—each similar to the impact of the bomb dropped on Hiroshima—in order to extract low-grade iron known as taconite. Waste rock with the potential to leech billions of gallons of sulfuric acid from what would be the largest open pit iron mine in the world could be dumped.”6 While the rhetoric here may seem exaggerated, the details are not.

The proposed mine would have targeted a band of iron-rich ore in the Penokee-Gogebic Range known as the Ironwood Formation that is a significant ore deposit in the national and indeed global context. Best estimates suggest that the Ironwood Formation contains at least 3.7 billion tons of taconite ore that could be mined economically, or 20 percent of known iron ore deposits in the United States. This translates into 1 billion tons of steel, or sixty-six years of domestic supply.7

This is such an enormous deposit, GTAC argued, that mining it was inevitable. The language of inevitability figured heavily in the pro-mining discussions. But, as U.S. Steel decided three decades earlier when it did bulk sampling and then decided not to mine taconite within the Ironwood Formation, its geological context made it an extremely difficult ore deposit to exploit without losing money.8 The rock is extremely hard (meaning one needs enormous blasting capabilities), and the deposit is tilted at a 65 degree angle, overlaid with 200–300 meters of overburden, and banded with quartzite and shale—all details that require extensive energy and infrastructure for extracting ore economically.

Environmental regulations for mines were much looser in the 1980s, and GTAC has never mined taconite. How, then, could GTAC propose to mine such a deposit, when U.S. Steel had decided it was impossible three decades before?9 The simplest way to mine taconite cheaply is to reduce labor and environmental costs. And that is what GTAC began to do in 2011, when rising steel prices in Asia made formerly uneconomic ore bodies seem plausible again. New, enormous mining machines have now been developed that can extract up to 200 tons of rock out of the mine in a single load, thus lowering labor costs.10 Reducing environmental costs would be possible if the industry could block the implementation of new federal standards that limit mercury emissions from the facilities needed to process taconite ore. And, if a company could persuade a state to exempt the industry from water quality regulations, tailings could be dumped cheaply into streams and wetlands.

Some environmental groups opposed to the GTAC mine argued that the Lake Superior basin and the Penokee-Gogebic Range in particular are essentially pristine and should never be mined. Residents of former iron-mining communities argued just the opposite: they said this has long been an iron-mining area, so it should continue to be one. Why did different groups have such different interpretations of the past, and how did these contested stories affect policy disputes?

Mining in the Lake Superior basin is not new, but the technologies for extensive extraction are recent. The first records of ore extraction date from thousands of years ago, with indigenous mining of copper ores on the Keweenaw Peninsula. Indians had exploited the mineral resources of the Keweenaw Peninsula on Lake Superior for at least 7,000 years, soon after the last glacier retreated. In the 1840s, word of copper deposits on the Keweenaw Peninsula spread to the East Coast and Europe.

Thousands of miners poured into the basin from Cornwall (where mines were laying off workers), eastern Europe, Italy, Finland, and elsewhere in the Americas. The federal government negotiated the Treaty of La Pointe in 1842 with the Anishinaabe nations, which required them to cede northern Wisconsin and the western half of the Upper Peninsula to the United States. Mining companies immediately moved into the area, exploiting first copper and then the rich iron ore deposits.

An 1848 report by A. Randall described the presence in the Penokee-Gogebic range of hematite iron ore, and extraction began in 1886. To the west in Minnesota, on the Mesabi Range, iron mining began with discovery of hematite iron ore in 1865; production followed in 1885 and rapidly expanded through the 1890s. In both places, mining efforts targeted the high-grade hematite ores that were concentrated and did not require extensive processing before being shipped across the Great Lakes to steel mills.11

By the early twentieth century, fully “85% of domestic ore production” came from soft, high-grade hematite ore mines on the U.S. side of the Lake Superior basin, in Michigan, Minnesota, and Wisconsin. Forty underground mines worked Wisconsin’s Ironwood Formation between 1877 and 1967, extracting 325 million tons that were shipped to blast furnaces in the lower Great Lakes.12 Mining towns such as Hurley, Ironwood, Iron River, and Montreal boomed briefly during the hematite era.

To reach the high-grade hematite deposits in the Penokee-Gogebic Range, miners dug deep shaft mines propped up with timbers from local forests. Waste rock was dumped near the mines, and some of these piles remain visible today. These mines did have environmental consequences: the shafts had to be dewatered to keep them from filling up with groundwater, and pumping the water from shafts into local streams presumably had some effect on watershed ecology. Some heavy metals were exposed to air, oxidizing and increasing the mobility of toxic metals into ecosystems and human bodies. Yet these consequences were much less extensive than open-pit taconite mining. As soon as the boom collapsed, first alder, then maple trees grew back, hiding the shaft holes and cloaking some of the slag piles, allowing people to imagine the forests as pristine and untouched.

The nineteenth-century mining boom had significant effects on Native communities. When the Anishinaabe were forced onto reservations in 1842 to make the rest of the region available to miners, disease, poverty, and despair often resulted. Yet the Anishinaabe successfully defended their right to remain on their homeland and its waters. They retained usufruct rights to the ceded territories, making certain that their members could continue to hunt, fish, and gather in perpetuity. These treaty rights have become central to the governance of mining conflicts in recent decades.

DEPLETION AND THE SHIFT TO TACONITE

As Jeffrey Manuel argues in this volume (see chapter 7), the shift to mining lower-grade taconite ore in the Lake Superior basin led to significant changes in environmental and political relationships. As early as the 1890s, mining engineers had argued that while surface deposits of the concentrated hematite appeared limited, beneath them lay extensive deposits of taconite. Hematite, in fact, is closely related to taconite, for it represents “the oxidized and purified surface weathering product of the much more extensive but lower grade taconite ore beneath.”13 Taconite was much more extensive, but because it lay buried under deep rock, and because it was such a low-grade ore, most engineers in the nineteenth century assumed it would be difficult to mine cost-effectively.

By the end of World War II, fears of iron ore depletion were becoming common. The war effort had demanded significant quantities of iron, and during the war, the range had supplied two-thirds of the ore for the U.S. military. After the war, a chorus of journalistic and engineering voices warned that the United States would soon run out of vital natural resources. Resource depletion, of course, is a cultural construct mediated by technology, rather than an absolute measure of a quantity of a resource. If all one has is a spoon, an ore body will be depleted for you as soon as the loose surface ore is scooped up. But if one has the 5.5 million–pound explosives that taconite operations now use, one can access entire ore bodies that were essentially invisible in earlier accounts of minerals because they were deemed impossible to mine.

As Manuel argues, depletion concerns in the Lake Superior basin were embedded in specific political contexts intended to generate pressure for government funds and new tax policies that would benefit taconite mines over hematite ore mines.14 While most iron production within the Lake Superior basin was sited on U.S. land, the waste from mining made its way into waters that were co-managed by the United States and Canada through the International Joint Commission. In other words, transnational contaminants complicated national boundaries. The pressures to develop new mines also reflecting growing global political interconnections. Depletion fears were framed within Cold War political concerns that helped mobilize state power to promote the shift to taconite mining. During the war, U.S. iron and steel companies had developed extensive networks of international iron sources.15 The economist Peter Kakela approvingly noted in 1978: “Rich ores were discovered on Canada’s Labrador-Quebec border and exploited by the Iron Ore Company of Canada, created in 1949 by Hanna Mining Company of Cleveland, Ohio. With the subsequent opening of the St. Lawrence Seaway in 1959, Canadian ore could be shipped more economically to steel mills bordering the Great Lakes.”16

By 1950, engineers were insisting that hematite depletion on the iron range demanded new funds, new tax policies, and relaxed environmental standards in order to ensure U.S. national security. For example, in a 1950 issue of the Science Newsletter, journalist Ann Ewing reminded readers that two world wars had depleted American hematite ore and, therefore, it was essential that taconite be developed, lest the nation become vulnerable to foreign manipulation.17 Ewing admitted that taconite development had significant environmental costs—particularly given that 48 tons of water would be needed for every ton of iron produced. Moreover, “the disposal of tailings presents a problem. They could be dumped on the ground, but it would take vast areas to accommodate them.”18 Recognizing that fishermen might object to dumping tailings in the lake that sustained the fisheries they relied upon, Ewing suggested that tailings in water might not seem ideal, but perhaps “the sand thus added to the lake will be helpful for the spawning of fish.”19

As Manuel argues, the most important mining engineer on Minnesota’s Iron Range, Edward Davis, was a longtime booster of taconite. He worked for decades to persuade a skeptical public that taconite ores could be processed cost-effectively, thus replacing hematite supplies. Davis initially borrowed processes that had been developed to work the low-grade copper deposits of Utah, recognizing that taconite was more like the western low-grade copper ores than eastern U.S. iron ore deposits.20

With taconite, mining for iron ore was to become less a simple matter of extracting some valuable ore from the ground (dangerous for miners, certainly, but less traumatic for the environment) than a matter of manufacturing production. As historian Timothy LeCain argues, the development of open-pit mining involved an increasingly mechanized system for extracting and refining large quantities of ore, often resulting in significant environmental destruction. Mining for copper ore—and eventually for taconite—became dominated by large corporations using enormous machines to extract low-grade deposits from open pits. LeCain describes the very visible environmental deterioration that accompanied open-pit copper mines in the U.S. West, including sulfur killing trees and clouds of poisonous gases contributing to lung diseases. In contrast, the toxicities from taconite were much subtler than those from copper, making them hard to unravel from more ordinary and easily detected forms of environmental degradation.21

TACONITE TOXICITIES: MERCURY AND ACID DRAINAGE

In the past three years, GTAC has done its best to present taconite as a safe ore to mine with minimal toxicity concerns. It is so safe and so pure, GTAC insisted before the Wisconsin legislature, that the state should quickly pass a new law exempting taconite mining from Wisconsin’s environmental regulations. The argument had two parts: first, because taconite itself rarely contains iron sulfides or pyrites—which can produce acid mine drainage—it’s pure. Second, the extraction process uses magnets and clean water, not hydrosulfuric acid.22

Technically, both of these details may be correct, but the conclusion that follows (therefore taconite mining has no toxicity concerns) ignores the larger geological and biological contexts of taconite within a watershed. First, taconite is a low-concentration iron ore, and to extract the valuable part, the rest of the rock (the tailings) must be crushed to a fine dust, mixed with water, then dewatered and stacked in piles or dumped into a body of water. These tailings particles are quite easily eroded by wind and water, and in this way they become mobilized into the watershed. At least 70 percent of the volume of the Ironwood Formation would be turned into waste and fine tailings, and the waste for the initial four-mile stage of mining alone would create a pile “600 million cubic yards” in size, stretching one mile square, 600 feet high.23

Second, there’s the problem of the 200–300 meters of so-called “overburden”; that is, the rock on top of the taconite itself, and the world on top of that rock. The very term overburden suggests that a living ecosystem—forests, forbs, birds, habitat, streams, the many different biological communities within the soil, the layers of rock that lie under the soil—is nothing but a burden that blocks the true resource, taconite. Anishinaabe peoples have increasingly resisted the terminology of mining, arguing that it renders invisible the biological, geological, and hydrological connections that sustain them.

While taconite may contain no pyrites or iron sulfide, the rock on top of it contains quite a bit of both. And there’s no way to get to that taconite without transforming the landscape into something that can cause acid mine drainage. GTAC denies the presence of pyritic ores in the formation (and the company has refused to allow the state, the tribes, or local citizens to view the samples that GTAC obtained from U.S. Steel). As long ago as 1929, however, the Wisconsin Geological Survey reported that pyrite is associated with local ore and waste rock, and a USGS report concluded the same thing in 2009. When ground to a fine dust (as required for taconite extraction), then exposed to oxygen and water, pyrites create sulfuric acid, which leaches harmful metals such as lead, arsenic, and mercury that make their way into groundwater and surface water.

Acid mine drainage represents an interesting mixture of natural and constructed toxicities. Many rock formations contain heavy metals that would be toxic if they were mobilized into biological systems. Typically, they’re bound in stable formations, where they don’t move into the atmosphere or the water supply on time scales that matter for biological life. (Over millions of years, of course, they do mobilize, so we’re talking about a matter of scale—spatial and temporal.) But when acid conditions are present, those chemicals and heavy metals do become mobilized into biological systems.

Wild rice is particularly sensitive to even extremely low levels of acidic drainage, creating enormous concerns for the tribes. Older taconite mines in Minnesota have continued to leach sulfates into wild rice beds decades after closure. Ecological history studies have shown that wild rice was abundant in the upper St. Louis River watershed (upstream from Duluth) before the 1950s, when taconite mining boomed. Currently, sulfate levels are high in the St. Louis River, and wild rice stands are few and stunted. The tailings basin once owned by LTV Taconite still leaches sulfates and other contaminates into the St. Louis River, and from there into Lake Superior. Elsewhere on the north shore, the Minntac taconite tailings basin is leaching 3 million gallons per day of sulfates and related pollutants into two watersheds. For decades, regulations in Minnesota have required very low sulfate levels to protect wild rice (10 milligrams per liter), yet not a single taconite mine is in compliance. Why has the Minnesota Pollution Control Agency (MPCA) been reluctant to enforce its own standards? Preliminary research suggests that because those standards are based on historical data, they have been vulnerable to criticism by legislators. One legislator in Minnesota has proposed to increase the state’s sulfate limit to 250 milligrams per liter, the level that models suggest is safe for adult drinking water. An unwillingness to interpret the evidence of historical change suggests that the boundaries between regulation, ecological history, and the mining industry remain contested.

What can these histories of mine problems tell communities that are trying to decide about new mine proposals? Christopher Dundas, chair of Duluth Metals Limited, argues that historical problems have no bearing on or relevance to the future proposed mines. “This is a completely different era than what happened in the ’60s,” Dundas has said. “Our operation will be state of the art and will be totally planned and designed to absolutely minimize every environmental issue.” History is irrelevant, in other words. But to advocates for the Boundary Waters, history matters. One opponent fears that problems with the Dunka taconite mine, near Babbitt, Minnesota, are “an indicator of problems to come” from proposed mines. Bruce Johnson, a former employee of a state agency that regulated Dunka and other local mining issues, told reporters that “he fears that state agencies will shortcut environmental rules because of the intense political pressure to approve mines and put people to work. ‘I want to have good jobs, too, but I want to do it right,’ Johnson said. ‘These guys are going to make multi-millions of dollars. We don’t want to be left with a bunch of mining pits full of polluted water that even ducks won’t land on.’”24

The Dunka mine was covered with sulfide rock similar to the overburden present in the Penokees. Its history suggests some of the difficulties of containing pyritic materials. LTV Steel operated the Dunka mine from 1964 to 1994, piling up more than 20 million tons of waste rock 80 to 100 feet high for almost a mile in length. Almost immediately, these waste piles began leaching copper, nickel, and other metals into wetlands and streams. Decades later, an average of 300,000–500,000 gallons continues to run off the piles every month, according to MPCA documents. Between 2005 and 2010, the runoff violated state water standards on nearly three hundred occasions. Rather than force LTV to spend the money to stop the toxic runoff, the MPCA fined the company that now owns the site (Duluth Metals Limited) $58,000—a cost of doing business that is far cheaper for the company than cleaning up the tailings. Yet this tainted water flows into the Boundary Waters Canoe Area, a federally designated wilderness area supposed to be protected from toxic discharges.

Mercury offers an excellent example of the complex relationships between ecological change, industrial development, and contamination data. In 2009, the U.S. Geological Survey reported that mercury contamination was found in every fish tested in nearly three hundred streams across the country.25 The highest levels of mercury were detected in some of the places most remote from industrial activity. Remoteness offers no protection, and the very richness of the remote wetlands increases their vulnerability to toxic conversions. Methylmercury finds its way into fish and eventually into the people eating that fish. Eating fish is of great cultural significance, particularly for indigenous communities in the basin. But its potential contamination forces communities to make trade-offs between their beliefs and possible harm to themselves. How much fish do you eat when it’s culturally important? How much do you eat when you’re pregnant? These are difficult dilemmas posed by changes in watershed health. Contaminants transform more than the health of lakes, fish, and forests; they also transform cultural identities. Interpreting the historic evidence of fish and human contamination has become a politically and culturally complex exercise.

Taconite processing is now the primary source of mercury produced within the Lake Superior basin, surpassing production from coal power plants. Minnesota’s taconite plants add 800 pounds per year of mercury to the basin, and a recent study found that 10 percent of newborn babies in the Lake Superior basin have mercury levels exceeding EPA standards.26 However, much of the mercury that actually accumulates within the basin comes not from local sources of production, but from global sources such as coal burning that have been transported via the atmosphere into the basin. This creates a tension: will controls on mercury emitted from local taconite processing actually reduce exposure to contaminants? Or will those controls indirectly increase exposures, if they shut down the local taconite industry, displacing production to China, which might then release greater levels of mercury emissions that return to Lake Superior waters, fish, and people? Unraveling local versus global sources and exposures presents enormous challenges for regulatory communities.

Mining, microbial ecology, and mercury interrelate in complex ways in the watershed. When mining exposes natural metal sulfides in ore bodies to air and water, oxidation results, leading to acid drainage. Microbes exist in many rocks, but usually in low numbers because lack of water and oxygen keeps them from reproducing. However, during the disturbance from mining, those microbes are exposed to water and oxygen, so their numbers multiply and they form colonies that can greatly accelerate the acidification processes. These sulfates also encourage conversion of elemental mercury (not particularly toxic) to methylmercury (extremely lethal), which then bioaccumulates in fish tissue and, from there, makes its way into wildlife and people.

ASBESTOS AND THE RESERVE MINING COMPANY

Between 1896 and 1900, the U.S. steel industry experienced a radical transformation. Small companies gave way to large, vertically integrated steel corporations that controlled not just steel mills but also the iron mines that supplied those mills.27 Nearly three-quarters of all Lake Superior iron ore in 1900 came from mines that were “either owned by or under long-term lease” to the largest American steel companies: Carnegie Steel, Federal Steel, National Steel, and several others—all to be absorbed into U.S. Steel in 1905.28 In 1947, the Reserve Mining Company—under the ownership of Armco Steel Corporation and Republic Steel Corporation—applied for permits to process taconite on the shores of Lake Superior near the small community of Silver Bay. Lake Superior would supply both the abundant water needed for taconite processing and a convenient location for tailings disposal. The company initially requested permits to deposit about 67,000 tons of tailings each day into the lake—eventually totaling 400 million tons of tailings before the permits expired. Once the mine reached full capacity, it produced 11 percent of the country’s total iron production and revitalized the faltering mining economy of the Lake Superior district.

Two decades later, conflicts over the toxic by-products of Reserve’s taconite mine—particularly asbestos fibers that made their way into Duluth’s drinking water and citizens—would lead to the most inflammatory environmental lawsuit in American history.29 Before granting permits, planners and regulators held a series of hearings to decide whether the tailings would be safe. The meanings of safety, however, were contested among the various stakeholders. Fishermen from communities along Minnesota’s north shore expressed concerns that tailings and water withdrawals might devastate fish habitat and ruin their economic base, while other citizens testified about their fears that silica in the tailings might lead to silicosis. Nevertheless, the state granted permits for the mine to dispose tailings directly into Lake Superior.

In 1947, Reserve Mining’s tailings disposal permits were made subject to three key conditions: first, that the tailings would not discolor the water outside narrowly defined areas; second, that the tailings would not harm fish in the lake; and third, that Reserve would be liable for any harm to water quality. The state reserved the right to revoke the permits if Reserve violated any of its conditions, including an important condition that discharge was not to include “material amounts of wastes other than taconite.”30 By the late 1950s, local environmental organizations, commercial fishermen, and sport-fishing groups were complaining to the MPCA that taconite tailings were killing fish and clouding the waters. The state refused to use its powers to intervene despite the conditions clearly written into the permits in 1947.31

Only after evidence emerged that asbestos had been mobilized from taconite disposal into the drinking water and bodies of urban residents distant from the disposal site did the federal and state governments officially begin to question risks from taconite. The plant’s exhaust stacks were also emitting asbestos-form fibers into the air. On behalf of the federal Environmental Protection Agency, the Department of Justice filed a lawsuit against Reserve in 1973, beginning a trial and appeals processes that would last for a decade. In early June 1973, Judge Miles Lord heard testimony from a specialist in asbestos exposure, Dr. Irving Seikoff, who confirmed that the city’s drinking water contained asbestos from the tailings. The concentration was surprisingly high: 100 billion fibers per liter of water, which was at least “‘1000 times higher’ than any asbestos level previously found in any water sample.”32

Reserve Mining Company disputed evidence about toxic mobilization, arguing in complex ways that asbestos could not possibly move from tailings into Lake Superior, from Lake Superior into drinking water, and from drinking water into lungs. Moreover, data suggesting toxicity did not always make it out of industry labs into regulatory spaces. In evidence presented at the trial on the ecological disruption caused by the tailings, Dr. Donald Mount of the EPA showed that Reserve was distorting the scientific process. The company designed studies with false controls in order to contaminate any possible findings, and it took measurements of tailings in places that it knew could not possibly show significant difference from controls.33

Discussions of new taconite mines continue to occur in the shadow of Reserve Mining Company’s release of tailings into Lake Superior and the resultant concern about asbestos exposure. When GTAC argues that taconite is perfectly safe, it interprets the Reserve Mining history as an example of what happens when environmentalists and regulators overreach and shut down a region’s economy for an unproven threat. For many environmentalists in the basin, in contrast, the Reserve Mining history suggests how treacherous taconite mining can be to water quality. Mine proponents counter by arguing that because new mines will stack tailings on land rather than dumping them into Lake Superior, one cannot draw a connection between an historical episode and a technologically advanced future. People who want the mines back point to a time when miners had good jobs, rarely mentioning the lung diseases that haunted the Iron Range or the collapse of economies when the companies pulled out. Mining opponents argue, in contrast, that historical economic benefits were outweighed by the costs of past toxic exposures. For these stakeholders, while the economic benefits did not remain, the health costs have lingered.

THE ANISHINAABE AND MINING ON CEDED TERRITORIES

The Reserve Mining Company historical precedent suggests how easy it is for scientific and legal discourses to miss what for the Anishinaabe community is the real point: clean water has values that go beyond what can be measured scientifically. And on ceded territories, members argue, the tribes have rights to comanagement of land and water resources, which means that their values must play as significant a role in policy making as other communities’ values. The federal government made three major land cession treaties with the Anishinaabe in the Lake Superior basin that established reservations to be under the exclusive control of the tribes (figure 11.3). Equally important, the tribes were careful to retain the right to hunt, fish, and gather on ceded territories, which also meant the right to participate in management of natural resources.34

State governments rarely recognized these ceded territory rights, until a series of brutal assaults took place in the late twentieth century. For decades, Wisconsin had arrested Anishinaabe who fished and hunted on ceded territories without state licenses, which the tribes insisted were unnecessary. In 1974, two members of the Lac Courte Oreilles Band were arrested for spearing fish on ceded territories. The Lac Courte Oreilles sued the state for treaty rights violation, and in 1983, the federal district court upheld off-reservation treaty rights in a landmark judgment called the Voight Decision. The state of Wisconsin appealed (and eventually lost). Meanwhile, white supremacist vigilantes (including members of the Hurley chapter of the Ku Klux Klan) attacked Anishinaabe spear fishers who were exercising their treaty rights, and a series of violent protests at fish landings marked the late 1980s. For all the violence, as geographer Zoltán Grossman argues, in the process of fighting each other, the tribes and the whites created a series of connections that the tribes were able to build upon a few years later, when Exxon proposed to build a copper and zinc mine (named Crandon) in sulfide-containing ore bodies within the watershed of the Wolf River (a National Wild and Scenic River). Like the GTAC mine, the Exxon mine would also have been located just upstream from an Anishinaabe reservation (the Mole Lake Sokaogon Band Reservation), within ceded territories.35 The state of Wisconsin had pushed for the mine, believing it would bring jobs to the north and money to the state. The Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources (DNR) decided to set standards for water leaving the mine at industrial water quality levels, allowing for 40 million tons of tailings and acidic mining waste that would have destroyed wild rice beds on the reservation. To stop the Crandon mine, the Mole Lake Sokaogon worked with the EPA to win the right to set its clean water standards.

Tribal lawyer Glenn Reynolds wrote regarding the case:

Wisconsin challenged the tribe’s authority to enact tribal water quality standards on the grounds that the federal government had already given Wisconsin primary authority over the state’s water resources and could not rescind that authority and pass it on to tribal governments. Ironically, Wisconsin argued that the Public Trust Doctrine granted the state the exclusive right to regulate, and potentially degrade, the water quality of Rice Lake on behalf of Wisconsin citizens. Unsurprisingly, the mining company supported Wisconsin’s stance. Three downstream towns and a village, however, filed a brief in support of the Sokaogon standards. After six years of litigation, the U.S. Supreme Court declined to review a federal appeals court decision that upheld the authority of the Sokaogon to set water standards necessary to protect reservation waters.36

Tribal efforts resulted in Wisconsin Act 171, passed in 1997, which became known as the “mining moratorium.” It required a moratorium on issuance of permits for mining of sulfide ore bodies until companies provided historical information proving that they had successfully controlled mining waste from their other mines for at least ten years.37

The other key issue that motivated mining activism among the Wisconsin tribes was the Bad River Band’s 1996 blockage of railroad tracks that would have brought sulfuric acid to a copper mine in White Pine, Michigan. On July 22, 1996, tribal members blockaded the railroad tracks that crossed their reservation, stopping a train headed for the White Pine copper mine in Upper Michigan. The train was carrying sulfuric acid that the mining company planned to experiment with in “solution-mining,” which would involve injecting 550 million U.S. gallons (2.1 million cubic meters) of acid into the mine to bring out the remaining copper ore. Environmentalists and tribal members raised concerns that the acid would contaminate groundwater and Lake Superior, but the EPA granted permission without first requiring a hearing or environmental impact statement. Anishinaabe activists insisted that the project was illegal because the EPA had failed to consult with affected Indian tribes, as required by law. In the face of legal battles over treaty rights, the company withdrew its mining permit application, and the White Pine copper mine and smelter shut down.38

After January 2011, when news of the GTAC’s proposed taconite mine in the Penokee Range first spread, the issue became extremely polarized. Because the proposed mine lay in ceded territories, the Anishinaabe tribes in the basin vowed to bring the fight against the mine out of a purely local and state discussion to a federal level, claiming violation of their tribal sovereignty. Local residents responded with death threats against tribal members, and a swirl of local, state, and federal lawsuits, hearings, and threats of violence marked the next four years. Debates over the mine became intense enough to swing a key election in Wisconsin. After the legislature defeated a pro-mining bill by one vote in March 2012, pro-mining groups donated $15.6 million dollars in campaign contributions and lobbying fees to candidates who might support a mine.39 The result was a change in control of the Wisconsin Senate (by one vote) after the November 2012 elections, giving the far right the power to rewrite Wisconsin laws.

In February 2013, a new mining bill, written with the help of GTAC lobbyists and the American Legislative Executive Council, was passed in Wisconsin that exempts taconite mining from many of the state’s water quality and wetlands standards.40 It formally establishes that the expansion of the iron-mining industry is a policy of the state. This means that if there is a conflict between a provision of the iron-mining laws and a provision in another state environmental law, the iron-mining law overrides other state laws.41

With enactment of the new law, the voice of the state became the only voice allowed in negotiations about permits. Local communities and the public lost the right to challenge state scientific findings and state permits. Contested case hearings—where the state had to face expert witnesses who could challenge their versions of the evidence—were outlawed. Citizen suits against a corporate or state employee alleged to be in violation of the metallic mining laws were also outlawed, even if the mine operator or state staff knowingly violated the law. In other words, the democratic processes by which outside voices could be heard to challenge state or corporate versions of scientific claims were outlawed, so that now an echo chamber exists. Senator Fred Risser (D-Madison), the longest-serving state legislator in U.S. history, expressed the anger of many when he thundered in the senate, “This bill is the biggest giveaway of resources since the days of the railroad barons.”42

The state of Wisconsin, however, cannot outlaw legal challenges from the Anishinaabe. The battle over the Mole Lake mine led to a U.S. Supreme Court decision in 2002 affirming the right of Indian nations to set and enforce their own clean air and water standards (working with the federal EPA). In other words, the state cannot set more relaxed standards.43 Even though a series of treaties between the U.S. government and sovereign Indian nations makes it clear that formal consultation is required before environmental permits are issued, the Wisconsin governor and legislature decided to ignore those requirements when drafting the new law. Senate majority leader Scott Fitzgerald (R-Juneau) said that he had no plans to consult with the Bad River Band during the drafting process. “It’s going to [be] difficult to ever get them on board,” he added.44

CONCLUSION

Contested interpretations of the past continue to shape current conflicts. People who want the mines back point to a time when miners had good jobs, rarely mentioning the lung diseases that haunted Iron Range miners, the bitter battles to win the few rights they had during the brief boom, or the collapse of economies when the companies pulled out. Pro-mining individuals in Hurley stated in interviews that they feel that they can trust the mining companies, so there’s no need for regulation or oversight. They remember a time when local-impact funds created good schools, decent hospitals, and well-maintained roads. But they forget that these benefits weren’t just handed to them by the company. They were won, bitterly, by political fights led by unions that have since lost much of their power. Companies left to themselves never gave us anything, one resident of Minnesota’s iron range said, concerned that new laws removed the protections that once marked the range.45

Events across scales shape the most local processes within the basin. When the Asian building boom in 2011 forced global steel prices to new highs, what had been just a pile of useless rock to U.S. Steel became reframed as the nation’s most important source of iron ore. Mining advocates insist the GTAC mine is inevitable in a global economy. “Only a primitive, backward people would stand in the way of our prosperity,” one white woman in Hurley said, complaining bitterly about the Bad River Band.46 But from the band’s perspective, how can we destroy the water, the wild rice, the rivers, the slough, for a few jobs and a billionaire’s profit? Water isn’t a resource to be commodified; it’s the blood at the heart of band members’ place and life.

Advocates point out that forbidding taconite mines in the Lake Superior basin will only shift more mining to other places, where environmental and labor protections may be even weaker than in today’s Wisconsin. And it’s true that the proportion of the world’s iron ore mined in Canada and the United States has dropped to only 1.3 percent of global production in 2010. (China, in contrast, mined 41.6% in 2015 and was still the world’s largest importer.)47 Yet who gets to decide which places, if any, are unsuitable for a mine? Who decides how to measure benefit versus harm? Are there going to be places where communities decide that the local, particular harms far outweigh the benefits on the regional or national scale? In a talk at Yale in March 2012, western historian Richard White spoke of “incommensurate measures.”48 What is gained in resource development by one group cannot simply be measured against what is lost by another group, he warned. At one mining hearing, Richard White’s incommensurate measures were in full force when pregnant women from the band spoke of their fears when they had to drink water poisoned by taconite mining.

There is nothing natural or inevitable about resource development. Resources are contingent and they change over time. Calling something a resource pulls it out of its intricate social and ecological relationships, isolates it in our gaze. Yet those isolations are illusions. We still live in intimate relationships with those elements, even if we think we don’t. The language of inevitability masks the fact that government actions promote one vision of resources over another. So treaty rights and environmental quality must bend to the march of progress. What’s hidden is the texture of the wild rice beds, the lake trout that swim through the waters of Lake Superior, the children of women poisoned by mercury, the asbestos released into the watershed by the processing of certain kinds of taconite deposits.

Selenium, mercury, arsenic—perfectly natural chemicals—lie bound and buried in rocks until miners release them while digging for something else that has become defined as a resource. Then as waters move through mining sites, these chemicals move the chemicals into fish bodies, and from there into human bodies. When minerals are dug from the ground, when trees are cut in the forest, when floodwaters are diverted, when rivers are dammed, when animals are changed from fellow creatures to livestock resources, we set into motion subtle processes of toxic transformation that have legacies far into the future.

Decisions about mine permitting are not purely scientific or technical decisions; they are also social decisions based, in part, on conflicting interpretations of historical and spatial dimensions of toxicity. Some, but not all, iron mines release sulfides into the water, which create acidic drainage that mobilizes toxics into the watershed. Some, but not all, iron mines include processing facilities that release mercury into the atmosphere, where it then mobilizes into the larger environment as methylmercury and bioaccumulates in fish. Some, but not all, iron mines release sulfates that mobilize heavy metals that can harm local wetlands and aquatic habitat. Whether or not a particular iron mine has toxic consequences depends partly on the geologic context, in particular the composition of the overburden (the rocks that cover the ore deposit). However, it is rarely the geology alone that leads to toxic exposures; social and political decisions about how to deploy contested scientific knowledge in the regulatory process ultimately shape toxic outcomes. Given that Lake Superior is the world’s largest lake (by surface area), the quality of its water has significance for the entire globe, particularly given the stresses that climate change is likely to place on freshwater.

NOTES

1. While this essay was in process, on February 27, 2015, the mining company announced that it was suspending operations at the site, citing concerns that the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency might have tried to block construction of the mine under provisions of the federal Clean Water Act. Susan Hedman, regional EPA administrator, denied any such intention.

2. The literature on Native American communities and environmental justice includes Jamie Donatuto and Darren Ranco, “Environmental Justice, American Indians, and the Cultural Dilemma: Developing Environmental Management for Tribal Health and Well-Being,” Environmental Justice 4:4 (December 2011): 221–30; James M. Grijalva, “Self-Determining Environmental Justice for Native America,” Environmental Justice 4:4 (December 2011): 187–92; Barbara Harper and Stuart Harris, “Tribal Environmental Justice: Vulnerability, Trusteeship, and Equity under NEPA,” Environmental Justice 4:4 (December 2011): 193–97; Jamie Vickery and Lori M. Hunter, Native Americans: Where in Environmental Justice Theory and Research? Institute of Behavior Science Population Program Working Paper (Boulder: University of Colorado, 2014); Kyle Powys Whyte, “Environmental Justice in Native America,” Environmental Justice 4:4 (December 2011): 185–86.

3. The Ramsar Convention on Wetlands, “USA Names Lake Superior Bog Complex,” September 3, 2012, http://www.ramsar.org/news/usa-names-lake-superior-bog-complex (last accessed February 7, 2017).

4. Glenn C. Reynolds, “A Native American Water Ethic,” Transactions of the Wisconsin Academy of Sciences, Arts and Letters 90 (2003): 146.

5. John Sandlos and Arn Keeling, “Claiming the New North: Development and Colonialism at the Pine Point Mine, Northwest Territories, Canada,” Environment and History 18:1 (2012): 5–34.

6. Rebecca Kemble, “The Walker Regime Pushes for Controversial Mining Law,” The Progressive, October 21, 2011.

7. Tom Fitz, “The Ironwood Iron Formation of the Penokee Range,” Wisconsin People and Ideas (Spring 2012): 33–39.

8. U.S. Steel had negotiated with The Nature Conservancy (TNC) to sell the company the mineral rights under the condition that the land be maintained for logging but that mining would not be allowed (thus reducing potential competition for U.S. Steel if steel prices rose enough to make mining the deposit profitable). But in the final stages of negotiation, for reasons that the TNC negotiator doesn’t understand, U.S. Steel pulled out and sold the mineral rights instead to RGGS Land and Minerals, Ltd., of Houston, Texas, and LaPointe Mining Co. in Minnesota. Matt Dallman, Director of Conservation, The Nature Conservancy, interview with the author, Wisconsin, May 2011.

9. The CEO of GTAC is Chris Cline, who has promoted longwall coal mining in Illinois, where his operations were cited fifty-three times over three years for violating water quality standards. Mary Annette Pember, “Chris Cline, the New King Coal, Likes to Swing His Big Iron Fist,” Indian Country Today, August 22, 2013. For a discussion of Clean Water Act violations, see Al Gedicks, “The Fight against Wisconsin’s Iron Mine,” Wisconsin Resources Protection Council, April 16, 2013, http://www.wrpc.net/articles/the-fight-against-wisconsins-iron-mine/ (accessed January 15, 2017).

10. Gedicks, “The Fight against Wisconsin’s Iron Mine.”

11. Fred W. Kohlmeyer, “Pioneering with Taconite,” Minnesota History 39:4 (1964): 163–64.

12. H.S. Harrison, “Where Is the Iron Ore Coming from?” Analysts’ Journal 9:33 (June 1953): 98–101.

13. Fitz, “The Ironwood Iron Formation of the Penokee Range.”

14. Jeffrey T. Manuel, “Mr. Taconite: Edward W. Davis and the Promotion of Low-Grade Iron Ore, 1913–1955,” Technology and Culture 54:2 (2013): 317–45.

15. John Thistle and Nancy Langston, “Entangled histories: Iron Ore Mining in Canada and the United States,” The Extractive Industries and Society, 2015, 14 July 2015, ISSN 2214–790X, http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.exis.2015.06.003. Bethlehem Steel Iron Company, for example, imported ore from Chile, and when the war ended, the company began developing large, high-grade concessions in Venezuela. U.S. Steel also began mining a hematite deposit in Venezuela, while Republic Steel Company developed hematite mines in Liberia.

16. Peter Kakela, “Iron Ore: From Depletion to Abundance,” Science 212:4491 (April 10, 1981): 132–36.

17. “The Venezuela iron ore deposits are rich and extensive,” Ewing admitted, but she then noted that “shipment of these or other high-grade foreign ores to the blast furnaces and steel mills in this country during an emergency might leave the ore-laden boats open to submarine attack.” Ann Ewing, “Low-Grade Ore Yields Iron,” Science News-Letter 57:20 (1950): 315.

18. Ibid., 314.

19. Ibid., 315.

20. Manuel, “Mr. Taconite.”

21. Timothy LeCain, Mass Destruction: The Men and Giant Mines That Wired America and Scarred the Planet (New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 2009).

22. Al Gedicks and Dave Blouin, “Science and Facts Show a Need for Tight Regulation of Taconite Mining,” Duluth News Tribune, February 13, 2013.

23. Ibid.

24. Dundas and Johnson quoted in Tom Meersman, “Runoff from Old Mines Raises Fears,” Minneapolis Star Tribune, October 1, 2010.

25. U.S. Geological Survey, Press release: “Mercury in Fish Widespread,” 2009, reported in Cornelia Dean, “Mercury Found in Every Fish Tested, Scientists Say,” New York Times, August 19, 2009, A19, http://www.nytimes.com/2009/08/20/science/earth/20brfs-MERCURYFOUND_BRF.html?_r=1&em.

26. Minnesota Department of Health Fish Consumption Advisory Program and MDH Public Health Laboratory, “Final Report to EPA: Mercury in Newborns in the Lake Superior Basin,” GLNPO ID 2007–942, November 30, 2011.

27. Terry S. Reynolds and Virginia P. Dawson. Iron Will: Cleveland-Cliffs and the Mining of Iron Ore, 1847–2006 (Detroit, MI: Wayne State University Press, 2011.

28. Richard B. Mancke, “Iron Ore and Steel: A Case Study of the Economic Causes and Consequences of Vertical Integration,” Journal of Industrial Economics 20:3 (1972): 222.

29. Michael E. Berndt and William C Brice, “The Origins of Public Concern with Taconite and Human Health: Reserve Mining and the Asbestos Case,” Regulatory Toxicology and Pharmacology 52:1, supplement (October 2008): S31.

30. Ibid., 33.

31. Ibid.

32. Thomas R. Huffman, “Enemies of the People: Asbestos and the Reserve Mining Trial,” Minnesota History 59:7 (2005): 296.

33. Office of Enforcement and General Counsel, Studies Regarding the Effect of the Reserve Mining Company Discharge on Lake Superior EPA, Washington, DC: U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, 1973). “The Reserve Mining Company performed [. . . an] in-situ study during 1972, to test algal stimulation by tailings. Unfortunately, they used as their control, water taken from a point very close to the discharge and the probabilities of contamination by tailings of this control water negates what might have been a useful study” (p. 14). In another section of the report, Mount described research by a federal scientist that gave the “first indication that tailings, through some mechanism, stimulate growth or prolong life of bacteria in Lake water. Reserve Mining Company has frequently said that such an effect could be due just to a ‘platform’ effect and not due to chemical stimulation. Their implication has been that the possible physical nature of this effect makes it unimportant. This is nonsense” (p. 10). Elsewhere, the testimony states: “A significant breakthrough was achieved in 1969 when cummingtonite, a mineral composing about 40% of the tailings, was recognized as a tracer for the discharge. [. . .] This method was unjustifiably challenged by Reserve Mining Company, because they measured stream sediment just downstream from bridges on highways on which they knew tailings had been used for ice control and construction, and then contended there was much more cummingtonite in the tributaries” (pp. 4–5).

34. Patty Loew, Indian Nations of Wisconsin: Histories of Endurance and Renewal, 2nd edition (Madison: Wisconsin Historical Society Press, 2013).

35. Zoltán Grossman, “Unlikely Alliances: Treaty Conflicts and Environmental Cooperation between Native American and Rural White Communities” (PhD dissertation, Department of Geography, University of Wisconsin–Madison, 2002).

36. Reynolds, “A Native American Water Ethic,” 154.

37. State of Wisconsin, 1997 Senate Bill 3, 1997 Wisconsin Act 171, enacted April 22, 1998, http://docs.legis.wisconsin.gov/1997/related/acts/171.pdf (accessed January 15, 2017).

38. Zoltán Grossman, “Chippewa Block Acid Shipments,” The Progressive, October 1, 1996.

39. “Mine Backers Drill with Big Cash to Ease Regulations,” Wisconsin Democracy Campaign, January 28, 2013, http://www.wisdc.org/pr012813.php (accessed August 24, 2014).

40. Senate Bill 1, Wisconsin Legislature, 2013–14, http://docs.legis.wisconsin.gov/2013/proposals/sb1 (accessed January 15, 2017). According to The Progressive, at least $1 million was donated to mining committee members’ campaign funds, and $15.6 million was given by “pro-mining interests to Governor Walker and other state legislators, outspending groups opposed to the measure 610 to 1.” R. Kemble, “Bad River Chippewa Take a Stand against Walker and Mining,” The Progressive, January 28, 2013. In August 2014, when evidence emerged that GTAC had secretly donated $700,000 to a political group helping Governor Scott Walker win election, the New York Times argued that Governor Walker had likely violated campaign finance laws. “How to Buy a Mine in Wisconsin: Did Gov. Scott Walker Violate Campaign Laws?” New York Times, August 31, 2014. Evidence of the donation is on p. 10 of the court document “Defendant Francis Schmitz’s Supplemental Opposition to Plaintiffs’ Motion for Preliminary Injunction,” Eric O’Keefe and Wisconsin Club for Growth, Inc. v. Francis Schmitz et al. (U.S. District Court for the Eastern District of Wisconsin, Milwaukee Division), Case No. 2:14-cv-00139-RTR, Case 14–2585, Document 44–6, http://www.jsonline.com/news/statepolitics/documents-governor-scott-walker-encouraged-donations-to-wisconsin-club-for-growth-john-doe-272369371.html (accessed January 15, 2017).

41. The new law diminishes water quality regulations, removing protections for streams and lake beds. Previously, the DNR was required to deny a mining permit if “irreparable damage to the environment” could not be prevented. Activities expected to cause substantial deposition in stream or lake beds, or the destruction or filling in of a lake bed, constituted grounds for denial. The 2013 law has removed these as bases for permit denial. It eliminates many of the state’s existing wetlands and watershed protections, reclassifying them as sacrifice zones. It includes a legislative finding that “because of the fixed location of ferrous mineral deposits in the state, it is probable that mining those deposits will result in adverse impacts to areas of special natural resource interest and to wetlands, including wetlands located within areas of special natural resource interest and that, therefore, the use of wetlands for bulk sampling and mining activities, including the disposal or storage of mining wastes or materials, or the use of other lands for mining activities that would have a significant adverse impact on wetlands, is presumed to be necessary.” State of Wisconsin, 2011–2012 Legislature, 2011 Bill Legislative Reference Bureau, 3520/1, “Analysis by the Legislative Reference Bureau,” p. 41, http://www.co.iron.wi.gov/docview.asp?docid=10246&locid=180 (accessed January 15, 2017).

42. Rebecca Kemble, “Walker’s Colossal Giveaway,” The Progressive, March 5, 2013.

43. Lee Bergquist, “Decision Puts Water Quality in Tribe’s Hands: Sokaogon Can Set Standard near Mine,” Milwaukee Journal Sentinel, June 4, 2002, 1A.

44. “Walker Pushes Mining Co.’s Bill, Despite Tribe’s Objections, The Progressive, January 8, 2013.

45. Hurley residents, interviews with author, December 31, 2011.

46. Ibid.

47. Wikipedia, s.v. “List of Countries by Iron Ore Production,” last modified November 30, 2016, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_countries_by_iron_ore_production.

48. Richard White, “Incommensurate Measures: Nature, History, and Economics,” Keynote Lecture, Yale University conference “Resources: Endowment or Curse, Better or Worse?” New Haven, CT, February 24, 2012.