Musée du Louvre

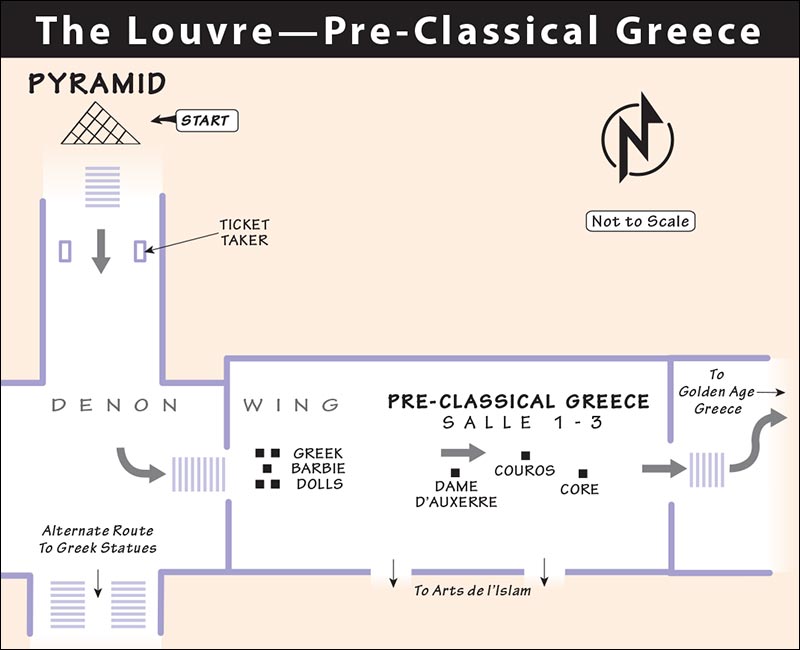

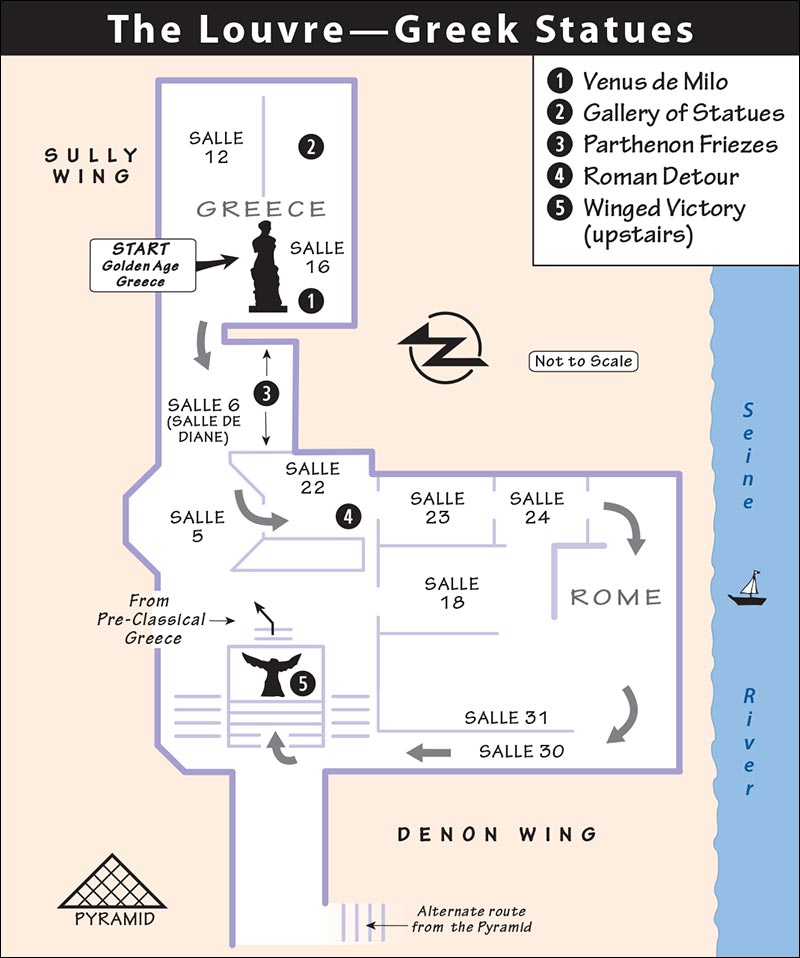

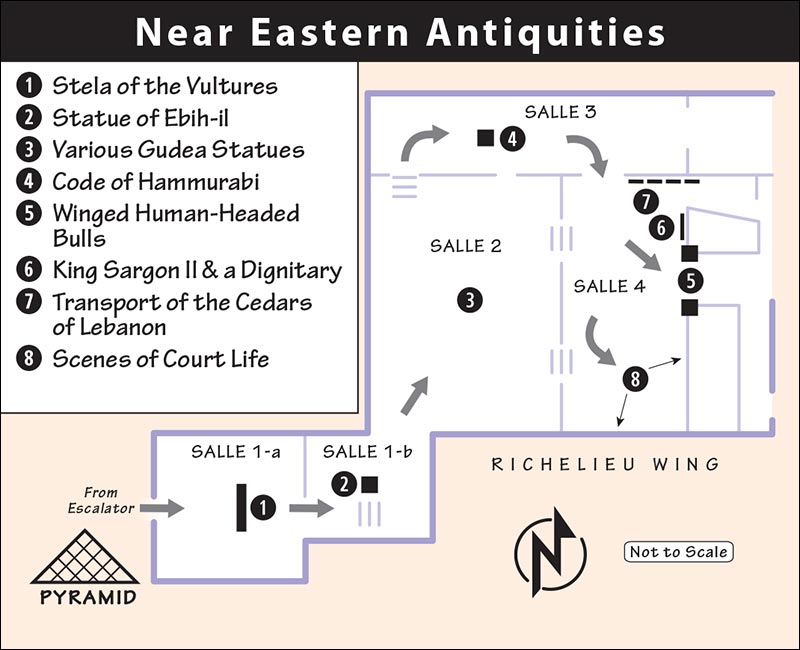

Map: The Louvre—Pre-Classical Greece

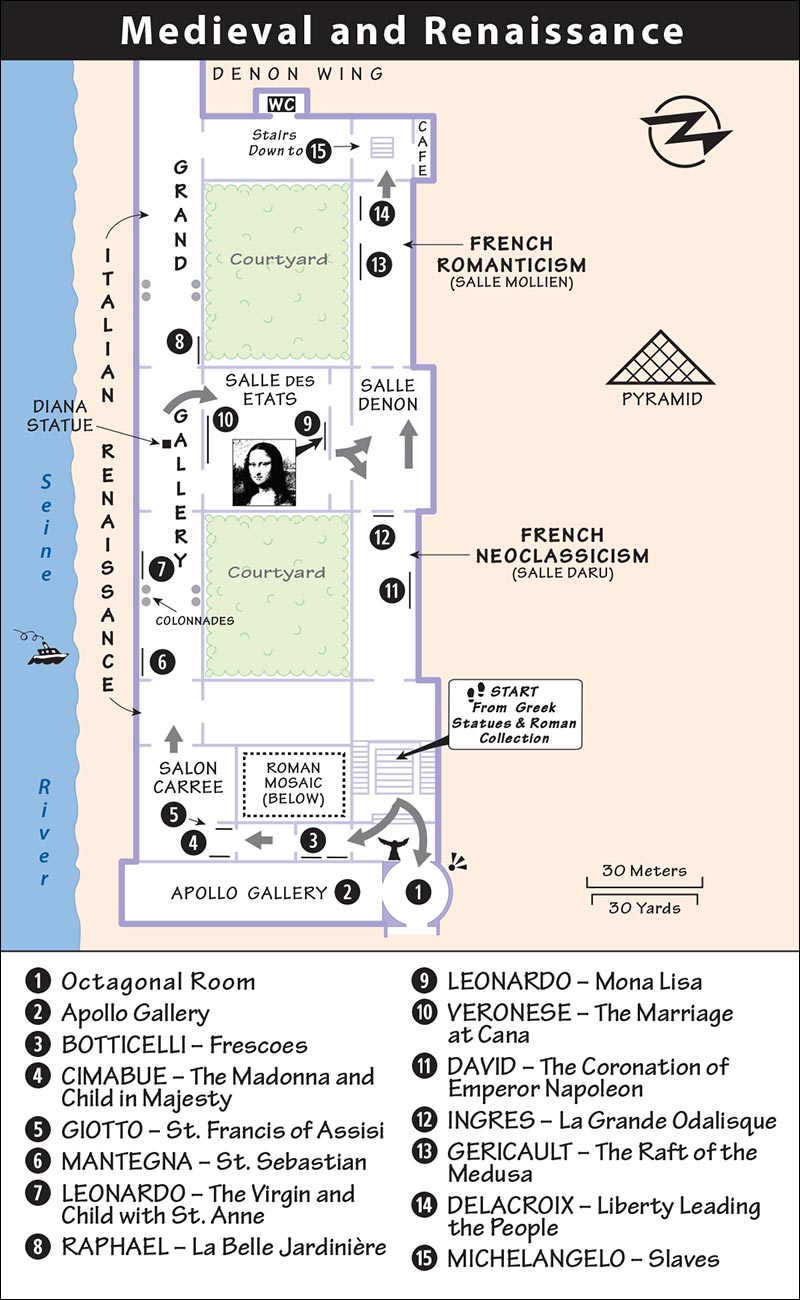

THE MEDIEVAL WORLD (1200-1500)

ITALIAN RENAISSANCE (1400-1600)

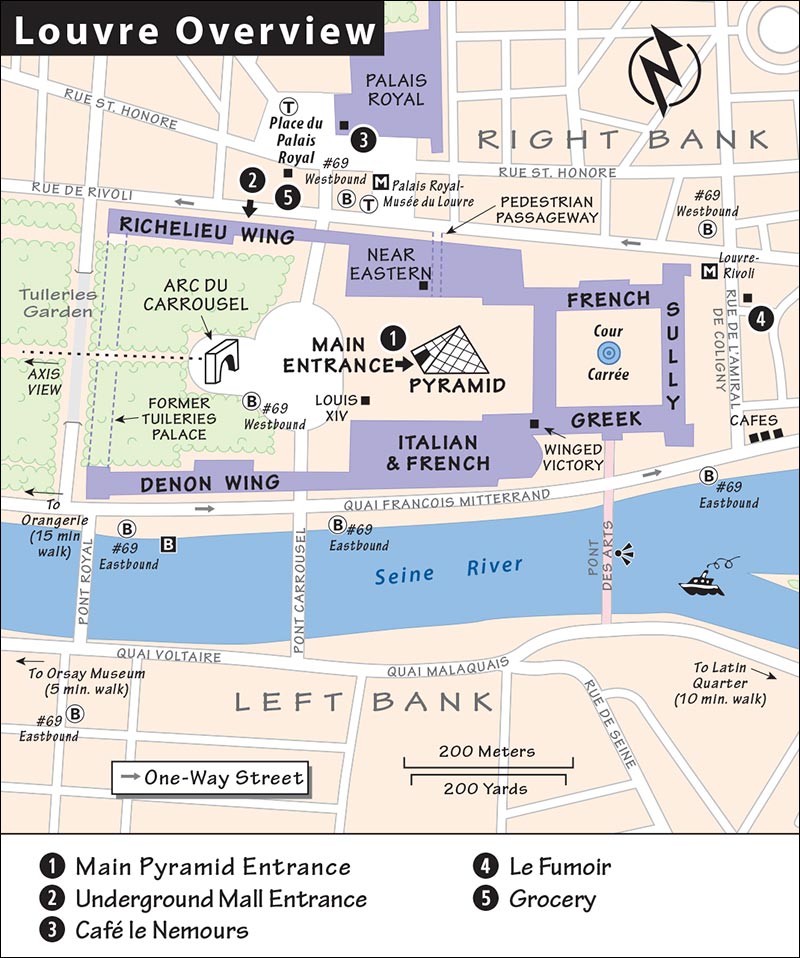

Paris walks you through world history in three world-class museums—the Louvre (ancient world to 1850), the Orsay (1848-1914, including Impressionism), and the Pompidou (20th century to today). Start your “art-yssey” at the Louvre. With more than 30,000 works of art, the Louvre is a full inventory of Western civilization. To cover it all in one visit is impossible. Let’s focus on the Louvre’s specialties—Greek sculpture, Italian painting, and French painting.

We’ll see “Venuses” through history, from prehistoric stick figures to the curvy Venus de Milo to the wind-blown Winged Victory of Samothrace, and from placid medieval Madonnas to the Mona Lisa to the symbol of modern democracy. Those with a little more time can visit some impressive chunks of stone from Mesopotamia—the “Cradle of Civilization” (modern-day Iraq). As we traverse the centuries, we’ll see how each generation defined beauty differently, and gain insight into long-ago civilizations by admiring what they found beautiful.

(See “Louvre Overview” map, here.)

Cost: €15, includes special exhibits, free on first Sun of month Oct-March only, covered by Museum Pass. Tickets good all day; reentry allowed.

Hours: Wed-Mon 9:00-18:00, open Wed and Fri nights until 21:45 (except on holidays), closed Tue. Galleries start shutting down 30 minutes before closing. Last entry is 45 minutes before closing.

Information: Tel. 01 40 20 53 17, recorded info tel. 01 40 20 51 51, www.louvre.fr.

When to Go: Crowds can be miserable on Sun, Mon (the worst day), Wed, and in the morning (arrive 30 minutes before opening to secure a good place in line). Evening visits are quieter, and the glass pyramid glows after dark.

The Smart Game Plan: For the popular and crowded Louvre you have two lines: security and ticket. Security lines are long but move pretty fast. (If security lines are very long and you already have a ticket or a Museum Pass, try the priority VIP security line outside at the pyramid—it’s your best option.) The ticket line is the avoidable one. If you already have a ticket or pass, once you pass security simply flash them at the wing of your choice (Denon for most) and you’re in. If you need a ticket upon arrival, you have three options: stand at the regular ticket office line under the pyramid (worst); use the self-serve machines (smarter, see next); or drop by the La Civette du Carrousel shop (smarter, see next).

Buying Tickets at the Louvre: Self-serve ticket machines located under the pyramid may be faster to use than the ticket windows (machines accept euro bills, coins, and chip-and-PIN Visa cards).

La Civette du Carrousel is a handy shop in the underground mall that sells tickets to the Louvre, Orsay, and Versailles, plus Museum Passes, for no extra charge (cash only). To find it from the Carrousel du Louvre entrance off Rue de Rivoli (described later), turn right after the last escalator down onto Allée de France, and follow Museum Pass signs.

Other Ticket-Buying Options: Timed-entry tickets are available online—see the Louvre website for details. Skip-the-line tickets (extra fee) are sold at FNAC stores and by Paris tour companies; see here.

Getting There: Métro stop Palais Royal-Musée du Louvre is the closest. From the station, you can stay underground to enter the museum, or exit above ground if you want to go in through the pyramid (more details later). The eastbound bus #69 stops along the Seine River; the best stop is labeled Quai François Mitterrand. The westbound #69 stops in front of the pyramid (see map on here for stop locations). You’ll find a taxi stand on Rue de Rivoli, next to the Palais Royal-Musée du Louvre Métro station.

Getting In: Enter through the pyramid, or opt for shorter lines elsewhere. Everyone must go through security checkpoints.

Main Pyramid Entrance: There is no grander entry than through the main entrance at the pyramid in the central courtyard. But the security line here can be very long. (If you have a ticket or a pass, go to the front and use the VIP line.)

Underground Mall Entrance: Anyone can enter the Louvre from its less crowded underground entrance, accessed through the Carrousel du Louvre shopping mall. Enter the mall at 99 Rue de Rivoli (the door with the red awning) or directly from the Métro stop Palais Royal-Musée du Louvre (stepping off the train, take the exit to Musée du Louvre-Le Carrousel du Louvre). Once inside the underground mall, continue toward the inverted pyramid next to the Louvre’s security entrance. Museum Pass holders can sometimes skip to the head of the security line, but if that special line is not obvious, don’t bother following signs pointing you to the Pyramid Passholders entrance (which is a long detour away).

Tours: Ninety-minute English-language guided tours leave twice daily (except the first Sun of the month Oct-March) from the Accueil des Groupes area, under the pyramid (normally at 11:00 and 14:00, possibly more often in summer; €12 plus admission, tour tel. 01 40 20 52 63). Videoguides (€5) provide commentary on about 700 masterpieces.

Download my free Louvre Museum audio tour, which complements the text in this chapter.

Download my free Louvre Museum audio tour, which complements the text in this chapter.

Length of This Tour: Allow at least two hours. With less time, string together the Venus de Milo, Winged Victory, Mona Lisa, and Coronation of Emperor Napoleon...and sightsee whatever else you can along the way.

Baggage Check: You can store bags for free in the Louvre’s slick self-service lockers (look for the Vestiaires sign). While bigger bags must be checked, you’ll be more comfortable in this exhausting place by checking whatever you don’t need—even if it’s just a small bag.

Services: WCs are located under the pyramid, behind the escalators to the Denon and Richelieu wings. Once you’re in the galleries, WCs are scarce.

Starring: Venus de Milo, Winged Victory, Mona Lisa, Leonardo da Vinci, Raphael, Michelangelo, the French painters, and many of the most iconic images of Western civilization.

Start by picking up the free map (Plan/Information) at the information desk beneath the glass pyramid as you enter, and take a moment to orient yourself.

The Louvre, the largest museum in the Western world, fills three wings of this immense, U-shaped palace. The Richelieu wing (north side) houses Near Eastern antiquities (covered in the last part of this tour), decorative arts, and French, German, and Northern European art. The Sully wing (east side) has extensive French painting and collections of ancient Egyptian and Greek art. The Denon wing (south side) houses Greek and Roman antiquities, as well as Italian, French, and Spanish paintings—plus an Islamic art exhibit.

We’ll concentrate on the Denon and Sully wings, which hold many of the superstars, including ancient Greek sculpture, Italian Renaissance painting, and French Neoclassical and Romantic painting.

The Louvre’s Map: The Louvre’s free map is detailed but confusing. To get oriented, find the Mona Lisa: She’s on level 1 (first floor), in Room 6 of the Denon wing. Our tour starts on level -1, under the pyramid; then we enter the Denon wing and turn left into Room 1.

Expect Changes: The sprawling Louvre is constantly shuffling its deck. Rooms close, and pieces can be on loan or in restoration. If you can’t find the artwork you’re looking for, ask the nearest guard for its new location. Point to the photo in your book and ask, “Où est, s’il vous plaît?” (oo ay, see voo play).

The Bottom Line: You could spend a lifetime here. Zero in on the biggies, and try to finish the tour with enough energy left to browse.

(See “Louvre Overview” map, here.)

• From inside the big glass pyramid, head for the Denon wing. Ride the escalator up one floor. After showing your ticket, continue ahead 25 paces, take the first left, follow the Antiquités Grecques signs, and climb a set of stairs to the brick-ceilinged Salle (Room) 1: Grèce Préclassique. Enter prehistory.

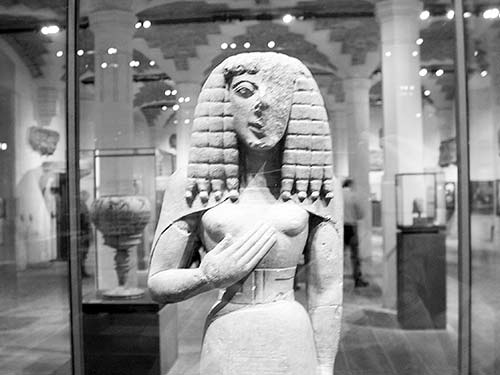

These statues are noble but crude. In the first glass cases, find Greek Barbie dolls (3000 B.C.) that are older than the pyramids—as old as writing itself. These prerational voodoo dolls whittle women down to their life-giving traits. Halfway down the hall, a miniature woman (Dame d’Auxerre) pledges allegiance to stability. Nearby, another woman (Core) is essentially a column with breasts. These statues stand like they have a gun to their backs—hands at sides, facing front, with sketchy muscles and mask-like faces. “Don’t move.”

The early Greeks, who admired statues like these, found stability more attractive than movement. Like their legendary hero Odysseus, the Greek people spent generations wandering, war-weary and longing for the comforts of a secure home. The strength and sturdiness of these works looked beautiful.

• Before moving on, note that the Islamic rooms are to the right. But we’ll continue on with ancient Greece.

Exit at the far end of the pre-Classical Greece galleries, and climb the stairs one flight. At the top, veer left (toward 11 o’clock), and continue into the Sully wing. After about 50 yards, turn right into Salle 16, where you’ll find Venus de Milo floating above a sea of worshipping tourists. It’s been said that among the warlike Greeks, this was the first statue to unilaterally disarm.

The great Greek cultural explosion that changed the course of history unfolded over 50 years (starting around 450 B.C.) in Athens, a town smaller than Muncie, Indiana. Having united Greece to repel a Persian invasion, Athens rebuilt, with the Parthenon as the centerpiece of the city. The Greeks dominated the ancient world using brains, not brawn, and their art shows their love of rationality, order, and balance. The ideal Greek was well-rounded—an athlete and a bookworm, a lover and a philosopher, a carpenter who played the lyre, a warrior and a poet. In art, the balance between timeless stability and fleeting movement made beauty.

In a sense, we’re all Greek: Democracy, mathematics, theater, philosophy, literature, and science were practically invented in ancient Greece. Most of the art that we’ll see in the Louvre either came from or was inspired by Greece.

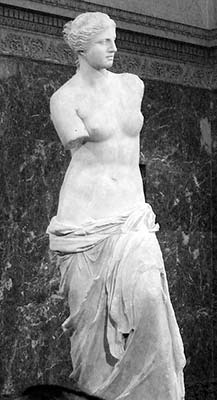

This goddess of love created a sensation when she was discovered in 1820 on the Greek island of Melos. Europe was already in the grip of a classical fad, and this statue seemed to sum up all that ancient Greece stood for. The Greeks pictured their gods in human form (meaning humans are godlike), telling us they had an optimistic view of the human race. Venus’ well-proportioned body captures the balance and orderliness of the Greek universe.

Split Venus down the middle from nose to toes and see how the two halves balance each other. Venus rests on her right foot (a position called contrapposto, or “counterpoise”), then lifts her left leg, setting her whole body in motion. As the left leg rises, her right shoulder droops down. And as her knee points one way, her head turns the other. Venus is a harmonious balance of opposites, orbiting slowly around a vertical axis. The twisting pose gives a balanced S-curve to her body (especially noticeable from the back view) that Golden Age Greeks and succeeding generations found beautiful.

Other opposites balance as well, like the smooth skin of her upper half that sets off the rough-cut texture of her dress (size 14). She’s actually made from two different pieces of stone plugged together at the hips (the seam is visible). The face is realistic and anatomically accurate, but it’s also idealized, a goddess, too generic and too perfect. This isn’t any particular woman, but Everywoman—all the idealized features that appealed to the Greeks.

Most “Greek” statues are actually later Roman copies. This is a rare Greek original. This “epitome of the Golden Age” was sculpted three centuries after the Golden Age, though in a retro style.

What were her missing arms doing? Some say her right arm held her dress, while her left arm was raised. Others say she was hugging a male statue or leaning on a column. I say she was picking her navel.

• Orbit Venus. This statue is interesting and different from every angle. Remember the view from the back—we’ll see it again later. Now make your reentry to earth. Follow Venus’ gaze and browse around the adjoining rooms (15, 14, and 13) of this long hall.

Greek statues feature the human body in all its splendor. The anatomy is accurate, and the poses are relaxed and natural. Around the fifth century B.C., Greek sculptors learned to capture people in motion and to show them from different angles, not just face-forward. The undoubted master was Praxiteles, whose lifelike statues set the tone for later sculptors. He pioneered the classic contrapposto pose—with the weight resting on one leg—capturing a balance between timeless stability and fleeting motion. The stance is not only more lifelike, but also intrinsically beautiful. If the statue has clothes, the robes drape down naturally, following the body’s curves. The intricate folds become part of the art.

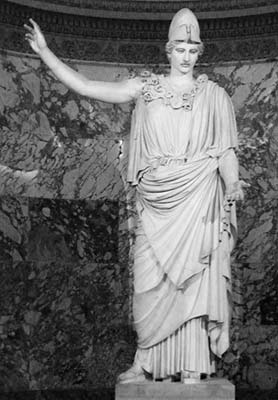

In this gallery, you’ll see statues of gods, satyrs, soldiers, athletes, and everyday people engaged in ordinary activities. For Athenians, the most popular goddess was their patron, Athena. She’s usually shown as a warrior, wearing a helmet and carrying a (missing) spear, ready to fight for her city. A monumental version of Athena stands at one end of the hall—the goddess of wisdom facing the goddess of love (Venus de Milo). Whatever the statue, Golden Age artists sought the perfect balance between down-to-earth humans (with human flaws and quirks) and the idealized perfection of Greek gods.

• Head to Salle 6 (also known as Salle de Diane), located behind the Venus de Milo. (Facing Venus, find Salle 6 to your right, back the way you came.) You’ll find two carved panels on opposite walls.

These stone fragments once decorated the exterior of the greatest Athenian temple, the Parthenon (see the scale model). Built at the peak of the Greek Golden Age, the temple glorified the city’s divine protector, Athena, and the superiority of the Athenians, who were feeling especially cocky, having just crushed their archrivals, the Persians. A model of the Parthenon shows where the panels might have hung. The centaur panel would have gone above the entrance. The panel of young women was placed under the covered colonnade, but above the doorway (to see it in the model, you’ll have to crouch way down and look up).

The panel on the right side of the room shows a centaur (half-human/half-horse) sexually harassing a woman, telling the story of how these rude creatures crashed a party of regular people. But the humans fought back and threw the brutes out, just as Athens had defeated its Persian invaders.

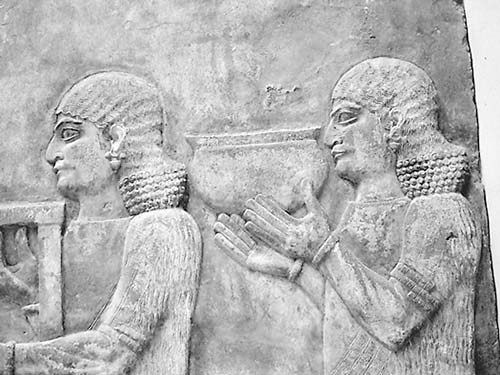

The other relief shows the sacred procession of young women who marched up the temple hill every four years with an embroidered shawl for the 40-foot-high statue of Athena, the goddess of wisdom (relief pictured at bottom of previous page). Though headless, the maidens speak volumes about Greek craftsmanship. Carved in only a couple of inches of stone, they’re amazingly realistic—more so than anything seen in the pre-Classical period. They glide along horizontally (their belts and shoulders all in a line), while the folds of their dresses drape down vertically. The man in the center is relaxed, realistic, and contrapposto. Notice the veins in his arm. The maidens’ pleated dresses make them look as stable as fluted columns, but their arms and legs step out naturally—their human forms emerging gracefully from the stone.

• Keep backtracking another 20 paces, turning left into Salle 22, the Roman Antiquities room (Antiquités Romaines), for a...

Stroll among the Caesars and try to see the person behind the public persona. Besides the many faces of the ubiquitous Emperor Inconnu (“unknown”), you might spot Augustus (Auguste), the first emperor, and his wily wife, Livia (Livie). Their son Tiberius (Tibère) was the Caesar that Jesus Christ “rendered unto.” Caligula was notoriously depraved, curly-haired Domitia murdered her husband, Hadrian popularized the beard, Trajan ruled the Empire at its peak, and Marcus Aurelius (Marc Aurèle) presided stoically over Rome’s slow fall.

The pragmatic Romans (500 B.C.-A.D. 500) were great conquerors but bad artists. One area in which they excelled was realistic portrait busts, especially of their emperors, who were worshipped as gods on earth. Fortunately for us, the Romans also had a huge appetite for Greek statues and made countless copies. They took the Greek style and wrote it in capital letters, adding a veneer of sophistication to their homes, temples, baths, and government buildings.

You’ll wander past several impressive sarcophagi while looping around a massive courtyard (Salle 31) with an impressive mosaic floor and beautiful wall-mounted mosaics from the ancient city of Antioch.

• To reach the Winged Victory continue clockwise through the Roman collection, which eventually spills out at the base of the stairs leading up to the first floor and the dramatic...

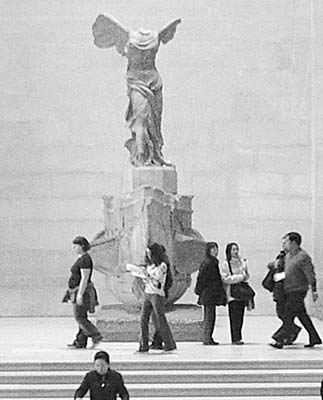

This woman with wings, poised on the prow of a ship, once stood on an island hilltop to commemorate a naval victory. Her clothes are windblown and sea-sprayed, clinging close enough to her body to win a wet T-shirt contest. (Look at the detail in the folds of her dress around the navel, curving down to her hips.) Originally, her right arm was stretched high, celebrating the victory like a Super Bowl champion, waving a “we’re number one” finger.

This is the Venus de Milo gone Hellenistic, from the time after the culture of Athens was spread around the Mediterranean by Alexander the Great (c. 325 B.C.). As Victory strides forward, the wind blows her and her wings back. Her feet are firmly on the ground, but her wings (and missing arms) stretch upward. She is a pillar of vertical strength, while the clothes curve and whip around her. These opposing forces create a feeling of great energy, making her the lightest two-ton piece of rock in captivity.

The earlier Golden Age Greeks might have considered this statue ugly. Her rippling excitement is a far cry from the dainty Parthenon maidens and the soft-focus beauty of Venus. And the statue’s off-balance pose, like an unfinished melody, leaves you hanging. But Hellenistic Greeks loved these cliff-hanging scenes of real-life humans struggling to make their mark.

In the glass case nearby is Victory’s open right hand with an outstretched finger, found in 1950, a century after the statue itself was unearthed. When the French learned the hand was in Turkey, they negotiated with the Turkish government for the rights to it. Considering all the other ancient treasures that France had looted from Turkey in the past, the Turks thought it only appropriate to give the French the finger.

• Enter the octagonal room to the left as you face the Winged Victory, with Icarus bungee-jumping from the ceiling. Find a friendly window and look out toward the pyramid.

Formerly a royal palace, the Louvre was built in stages over eight centuries. On your right (the Sully wing) was the original medieval fortress. About 500 yards to the west, in the now-open area past the pyramid and the triumphal arch, is where the Tuileries Palace used to stand. Succeeding kings tried to connect these two palaces, each monarch adding another section onto the long, skinny north and south wings. Finally, in 1852, after three centuries of building, the two palaces were connected, creating a rectangular Louvre. Nineteen years later, the Tuileries Palace burned down during a riot, leaving the U-shaped Louvre we see today.

The glass pyramid was designed by the Chinese-born American architect I. M. Pei (1989). Many Parisians initially hated the pyramid, just as they hated another new and controversial structure 100 years earlier—the Eiffel Tower.

In the octagonal room, find the plaque at the base of the dome. The inscription reads: “Le Musée du Louvre, fondé le 16 Septembre, 1792.” The museum was founded by France’s Revolutionary National Assembly—the same people who brought you the guillotine. What could be more logical? You behead the king, inherit his palace and art collection, open the doors to the masses, and voilà! You have Europe’s first public museum.

• From the octagonal room, enter the Apollo Gallery (Galerie d’Apollon).

This gallery gives us a feel for the Louvre as the glorious home of French kings (before Versailles). Imagine a chandelier-lit party in this room, drenched in stucco and gold leaf, with tapestries of leading Frenchmen and paintings featuring mythological and symbolic themes. The crystal vases, the inlaid tables made from marble and semiprecious stones, and many other art objects show the wealth of France, Europe’s number-one power for two centuries. Portraits on the walls depict great French kings: Henry IV, who built the Pont Neuf; Louis XIV, the Sun King; and François I, who brought Leonardo da Vinci (and the Italian Renaissance) to France.

Stroll past glass cases of royal dinnerware to the far end of the room. In a glass case are the crown jewels. The display varies, but you may see the jewel-studded crowns of Louis XV and the less flashy Crown of Charlemagne (the only crowns to escape destruction in the Revolution), along with the 140-carat Regent Diamond, which once graced crowns worn by Louis XV, Louis XVI, and Napoleon.

• A rare WC is a half-dozen rooms away, near Salle 38 in the Sully wing. The Italian collection (Peintures Italiennes) is on the other side of Winged Victory. Cross back in front of Winged Victory and enter the Denon wing and Salle 1, where you’ll find...

Look at the paintings on the wall to the left. These pure maidens, like colorized versions of the Parthenon frieze, give us a preview of how ancient Greece would be “reborn” in the Renaissance.

• But first, the Medieval World. Continue into the large Salle 3.

During the Age of Faith (1200s), almost every church in Europe had a painting like this one. Mary was a cult figure—even bigger than the late-20th-century Madonna—adored and prayed to by the faithful for bringing Baby Jesus into the world. After the collapse of the Roman Empire (c. A.D. 500), medieval Europe was a poor and violent place, with the Christian Church as the only constant in troubled times.

Altarpieces tended to follow the same formula: somber iconic faces, stiff poses, elegant folds in the robes, and generic angels. Violating the laws of perspective, the angels at the “back” of Mary’s throne are the same size as those holding the front. These holy figures are laid flat on a gold background like cardboard cutouts, existing in a golden never-never land, as though the faithful couldn’t imagine them as flesh-and-blood humans inhabiting our dark and sinful earth.

• Do a 180 and find...

Francis of Assisi (c. 1181-1226), a wandering Italian monk of renowned goodness, kneels on a rocky Italian hillside, pondering the pain of Christ’s torture and execution. Suddenly, he looks up, startled, to see Christ himself, with six wings, hovering above. Christ shoots lasers from his wounds to the hands, feet, and side of the empathetic monk, marking him with the stigmata. Francis went on to breathe the spirit of the Renaissance into medieval Europe. His humble love of man and nature inspired artists like Giotto to portray real human beings with real emotions, living in a physical world of beauty.

Like a good filmmaker, Giotto (c. 1266-1337) doesn’t just tell us what happened, he shows us in the present tense, freezing the scene at its most dramatic moment. Though the perspective is crude—Francis’ hut is smaller than he is, and Christ is somehow shooting at Francis while facing us—Giotto creates the illusion of three dimensions, with a foreground (Francis), middle ground (his hut), and background (the hillside). Painting a 3-D world on a 2-D surface is tough, and after a millennium of Dark Ages, artists were rusty.

In the predella (the panel of paintings beneath the altarpiece), birds gather at Francis’ feet to hear him talk about God. Giotto catches the late arrivals in midflight, an astonishing technical feat for an artist working more than a century before the Renaissance. The simple gesture of Francis’ companion speaks volumes about his amazement. Breaking the stiff, iconic mold for saints, Francis bends forward at the waist to talk to his fellow creatures. The diversity of the birds—“red and yellow, black and white”—symbolizes how all humankind is equally precious in God’s sight. Meanwhile, the tree bends down symmetrically to catch a few words from the beloved hippie of Assisi.

• The long Grand Gallery displays Italian Renaissance painting—some masterpieces, some not.

Built in the late 1500s to connect the old palace with the Tuileries Palace, the Grand Gallery displays much of the Louvre’s Italian Renaissance art. From the doorway, look to the far end and consider this challenge: I hold the world record for the Grand Gallery Heel-Toe-Fun-Walk-Tourist-Slalom, going end to end in 1 minute, 58 seconds (only two injured). Time yourself. Along the way, notice some of the features of Italian Renaissance painting:

• Religious: Lots of Madonnas, children, martyrs, and saints.

• Symmetrical: The Madonnas are flanked by saints—two to the left, two to the right, and so on.

• Realistic: Real-life human features are especially obvious in the occasional portrait.

• Three-Dimensional: Every scene gets a spacious setting with a distant horizon.

• Classical: You’ll see some Greek gods and classical nudes, but even Christian saints pose like Greek statues, and Mary is a Venus whose face and gestures embody all that was good in the Christian world.

Not the patron saint of acupuncture, St. Sebastian was a Christian martyr, although here he looks more like a classical Greek statue. Notice the contrapposto stance (all his weight resting on one leg) and the Greek ruins scattered around him. His executioners look like ignorant medieval brutes bewildered by this enlightened Renaissance Man. Italian artists were beginning to learn how to create human realism and earthly beauty on the canvas. Let the Renaissance begin.

• Look for the following masterpieces by Leonardo 50 yards down the Grand Gallery, on the left.

Three generations—grandmother, mother, and child—are arranged in a pyramid, with Anne’s face as the peak and the lamb as the lower right corner. Within this balanced structure, Leonardo sets the figures in motion. Anne’s legs are pointed to our left. (Is Anne Mona? Hmm.) Her daughter Mary, sitting on her lap, reaches to the right. Jesus looks at her playfully while turning away. The lamb pulls away from him. But even with all the twisting and turning, this is still a placid scene. It’s as orderly as the geometrically perfect universe created by the Renaissance god.

There’s a psychological kidney punch in this happy painting. Jesus, the picture of childish joy, is innocently playing with a lamb—the symbol of his inevitable sacrificial death.

The Louvre has the greatest collection of Leonardos in the world—five of them. Look for the neighboring Virgin of the Rocks and John the Baptist. Leonardo was the consummate Renaissance Man; a musician, sculptor, engineer, scientist, and sometime painter, he combined knowledge from all these areas to create beauty. If he were alive today, he’d create a Unified Field Theory in physics—and set it to music.

• You’ll likely find Raphael’s art on the right side of the Grand Gallery, just past the statue of Diana the Huntress.

Raphael perfected the style Leonardo pioneered. This configuration of Madonna, Child, and John the Baptist is also a balanced pyramid with hazy grace and beauty. Mary is a mountain of maternal tenderness (the title translates as “The Beautiful Gardener”) as she eyes her son with a knowing look and holds his hand in a gesture of union. Jesus looks up innocently, standing contrapposto like a chubby Greek statue. Baby John the Baptist kneels lovingly at Jesus’ feet, holding a cross that hints at his playmate’s sacrificial death. The interplay of gestures and gazes gives the masterpiece both intimacy and cohesiveness, while Raphael’s blended brushstrokes varnish the work with an iridescent smoothness.

With Raphael, the Greek ideal of beauty—reborn in the Renaissance—reached its peak. His work spawned so many imitators who cranked out sickly sweet, generic Madonnas that we often take him for granted. Don’t. This is the real thing.

• The Mona Lisa (La Joconde) is a few steps away from the black statue of Diana, in Salle 6. Mona is alone behind glass on her own false wall. Six million heavy-breathing people crowd in each year to glimpse the most ogled painting in the world. (You can’t miss her. Just follow the signs and the people...it’s the only painting you can hear. With all the groveling crowds, you can even smell it.)

Leonardo was already an old man when François I invited him to France. Determined to pack light, he took only a few paintings with him. One was a portrait of Lisa del Giocondo, the wife of a wealthy Florentine merchant. When Leonardo arrived, François immediately fell in love with the painting, making it the centerpiece of the small collection of Italian masterpieces that would, in three centuries, become the Louvre museum. He called it La Gioconda (La Joconde in French)—a play on both her last name and the Italian word for “happiness.” We know it as the Mona Lisa—a contraction of the Italian for “my lady Lisa.”

Mona may disappoint you. She’s smaller than you’d expect, darker, engulfed in a huge room, and hidden behind a glaring pane of glass. So, you ask, “Why all the hubbub?” Let’s take a closer look. As you would with any lover, you’ve got to take her for what she is, not what you’d like her to be.

The famous smile attracts you first. Leonardo used a hazy technique called sfumato, blurring the edges of her mysterious smile. Try as you might, you can never quite see the corners of her mouth. Is she happy? Sad? Tender? Or is it a cynical supermodel’s smirk? All visitors read it differently, projecting their own moods onto her enigmatic face. Mona is a Rorschach inkblot...so, how are you feeling?

Now look past the smile and the eyes that really do follow you (most eyes in portraits do) to some of the subtle Renaissance elements that make this painting work. The body is surprisingly massive and statue-like, a perfectly balanced pyramid turned at an angle, so we can see its mass. Her arm rests lightly on the armrest of a chair, almost on the level of the frame itself, as if she’s sitting in a window looking out at us. The folds of her sleeves and her gently folded hands are remarkably realistic and relaxed. The typical Leonardo landscape shows distance by getting hazier and hazier.

Though the portrait is generally accepted as a likeness of Lisa del Giocondo, other hypotheses about the sitter’s identity have been suggested, including the idea that it’s Leonardo himself. Or she might be the Mama Lisa. A recent infrared scan revealed that she has a barely visible veil over her dress, which may mean (in the custom of the day) that she had just had a baby.

The overall mood is one of balance and serenity, but there’s also an element of mystery. Mona’s smile and long-distance beauty are subtle and elusive, tempting but always just out of reach, like strands of a street singer’s melody drifting through the Métro tunnel. Mona doesn’t knock your socks off, but she winks at the patient viewer.

• Before leaving Mona, step back and just observe the paparazzi scene. The huge canvas opposite Mona is...

Stand 10 steps away from this enormous canvas to where it just fills your field of vision, and suddenly...you’re in a party! Help yourself to a glass of wine. This is the Renaissance love of beautiful things gone hog-wild. Venetian artists like Veronese painted the good life of rich, happy-go-lucky Venetian merchants.

In a spacious setting of Renaissance architecture, colorful lords and ladies, decked out in their fanciest duds, feast on a great spread of food and drink, while the musicians fuel the fires of good fun. Servants prepare and serve the food, jesters play, and animals roam. In the upper left, a dog and his master look on. A sturdy linebacker in yellow pours wine out of a jug (right foreground). The man in white samples some and thinks, “Hmm, not bad,” while nearby a ferocious cat battles a lion. The wedding couple at the far left is almost forgotten.

Believe it or not, this is a religious work showing the wedding celebration in which Jesus turned water into wine. And there’s Jesus in the dead center of 130 frolicking figures, wondering if maybe wine coolers might not have been a better choice. With true Renaissance optimism, Venetians pictured Christ as a party animal, someone who loved the created world as much as they did.

Now, let’s hear it for the band! On bass—the bad cat with the funny hat—Titian the Venetian! And joining him on viola—Crazy Veronese!

• Exit behind Mona into the Salle Denon (Room 76). The dramatic Romantic room is to your left, and the grand Neoclassical room is to your right. These two rooms feature the most exciting French canvases in the Louvre. Turn right into the Neoclassical room (Salle Daru) and kneel before the largest canvas in the Louvre.

Napoleon holds aloft an imperial crown. This common-born son of immigrants is about to be crowned emperor of a “New Rome.” He has just made his wife, Josephine, the empress, and she kneels at his feet. Seated behind Napoleon is the pope, who journeyed from Rome to place the imperial crown on his head. But Napoleon feels that no one is worthy of the task. At the last moment, he shrugs the pope aside, grabs the crown, holds it up for all to see...and crowns himself. The pope looks p.o.’d.

After the French people decapitated their king during the Revolution (1793), their fledgling democracy floundered in chaos. France was united by a charismatic, brilliant, temperamental, upstart general who kept his feet on the ground, his eyes on the horizon, and his hand in his coat—Napoleon Bonaparte. Napoleon quickly conquered most of Europe and insisted on being made emperor (not merely king). The painter David (dah-VEED) recorded the coronation for posterity.

The radiant woman in the gallery in the background center wasn’t actually there. Napoleon’s mother couldn’t make it to see her boy become the most powerful man in Europe, but he had David paint her in anyway. (There’s a key on the frame telling who’s who in the picture.)

The traditional setting for French coronations was the ultra-Gothic Notre-Dame cathedral. But Napoleon wanted a location that would reflect the glories of Greece and the grandeur of Rome. So, interior decorators erected stage sets of Greek columns and Roman arches to give the cathedral the architectural political correctness you see in this painting. (The pietà statue on the right edge of the painting is still in Notre-Dame today.)

David was the new emperor’s official painter and propagandist, in charge of color-coordinating the costumes and flags for public ceremonies and spectacles. (Find his self-portrait with curly gray hair in the Coronation, way up in the second balcony, peeking around the tassel directly above Napoleon’s crown.) His “Neoclassical” style influenced French fashion. Take a look at his Madame Juliet Récamier portrait on the opposite wall, showing a modern Parisian woman in ancient garb and Pompeii hairstyle reclining on a Roman couch. Nearby paintings, such as The Oath of the Horatii (Le Serment des Horaces), are fine examples of Neoclassicism, with Greek subjects, patriotic sentiment, and a clean, simple style.

• As you double back toward the Romantic room, stop at...

Take Venus de Milo, turn her around, lay her down, and stick a hash pipe next to her, and you have the Grande Odalisque. OK, maybe you’d have to add a vertebra or two.

Using clean, polished, sculptural lines, Ingres (ang-gruh) exaggerates the S-curve of a standing Greek nude. As in the Venus de Milo, rough folds of cloth set off her smooth skin. Ingres gave the face, too, a touch of Venus’ idealized features, taking nature and improving on it. Contrast the cool colors of this statue-like nude with Titian’s golden girls. Ingres preserves Venus’ backside for posterior—I mean, posterity.

• Cross back through the Salle Denon and into Room 77, gushing with French Romanticism.

In the artistic war between hearts and minds, the heart style was known as Romanticism. Stressing motion and emotion, it was the flip side of cool, balanced Neoclassicism, though they both flourished in the early 1800s.

What better setting for an emotional work than a shipwreck? Clinging to a raft is a tangle of bodies and lunatics sprawled over each other. The scene writhes with agitated, ominous motion—the ripple of muscles, churning clouds, and choppy seas. On the right is a deathly green corpse dangling overboard. The face of the man at left, cradling a dead body, says it all—the despair of spending weeks stranded in the middle of nowhere.

This painting was based on the actual sinking of the ship Medusa off the coast of Africa in 1816. About 150 people packed onto the raft. After floating in the open seas for 12 days—suffering hardship and hunger, even resorting to cannibalism—only 15 survived. The story was made to order for a painter determined to shock the public and arouse its emotions. That painter was young Géricault (ZHAIR-ee-ko). He interviewed survivors and honed his craft, sketching dead bodies in the morgue and the twisted faces of lunatics in asylums, capturing the moment when all hope is lost.

But wait. There’s a stir in the crowd. Someone has spotted something. The bodies rise up in a pyramid of hope, culminating in a flag wave. They signal frantically, trying to catch the attention of the tiny ship on the horizon, their last desperate hope...which did finally save them. Géricault uses rippling movement and powerful colors to catch us up in the excitement. If art controls your heartbeat, this is a masterpiece.

The year is 1830. King Charles has just issued the 19th-century equivalent of the Patriot Act, and his subjects are angry. Parisians take to the streets once again, Les Miz-style, to fight royalist oppressors. The people triumph—replacing the king with Louis-Philippe, who is happy to rule within the constraints of a modern constitution. There’s a hard-bitten proletarian with a sword (far left), an intellectual with a top hat and a sawed-off shotgun, and even a little boy brandishing pistols.

Leading them on through the smoke and over the dead and dying is the figure of Liberty, a strong woman waving the French flag. Does this symbol of victory look familiar? It’s the Winged Victory, wingless and topless.

To stir our emotions, Delacroix (del-ah-kwah) uses only three major colors—the red, white, and blue of the French flag. France is the symbol of modern democracy, and this painting has long stirred its citizens’ passion for liberty. The French weren’t the first to adopt democracy in its modern form (Americans were), nor are they the best working example of it, but they’ve had to try harder to achieve it than any other country. No sooner would they throw one king or dictator out than they’d get another. They’re now working on their fifth republic.

This symbol of freedom is a fitting tribute to the Louvre, the first museum ever opened to the common rabble of humanity. The good things in life don’t belong only to a small, wealthy part of society, but to everyone. The motto of France is Liberté, Egalité, Fraternité—liberty, equality, and brotherhood for all.

• Exit the room at the far end (past the Café Mollien) and go downstairs, where you’ll bump into the bum of a large, twisting male nude looking like he’s just waking up after a thousand-year nap.

These two statues by the earth’s greatest sculptor are a bridge between the ancient and modern worlds. Michelangelo, like his fellow Renaissance artists, learned from the Greeks. The perfect anatomy, twisting poses, and idealized faces appear as if they could have been created 2,000 years earlier.

The so-called Dying Slave (also called the Sleeping Slave, looking like he should be stretched out on a sofa) twists listlessly against his T-shirt-like bonds, revealing his smooth skin. Compare the polished detail of the rippling, bulging left arm with the sketchy details of the face and neck. With Michelangelo, the body does the talking. This is probably the most sensual nude that Michelangelo, the master of the male body, ever created.

The Rebellious Slave fights against his bondage. His shoulders rotate one way, his head and leg turn the other. He looks upward, straining to get free. He even seems to be trying to release himself from the rock he’s made of. Michelangelo said that his purpose was to carve away the marble to reveal the figures God put inside. This slave shows the agony of that process and the ecstasy of the result.

• Tour over! These two may be slaves of the museum, but you are free to go. You’ve seen the essential Louvre. But no Louvre visit is complete without first taking a photo alongside the statue located 20 paces away, which I believe is titled “Apollo Taking Selfie.” Or, for romantics, continue to the far corner of the room (on the right), and swoon at Antonio Canova’s sculpture Psyche Revived by Cupid’s Kiss.

To leave the museum, continue out this hall, take four steps down, notice the iconic pyramid outside the windows on the left (where you’re heading), and turn right, following signs down the stairs to the Sortie.

But, of course, there’s so much more. After a break (or on a second visit), consider a stroll through a few rooms of the Richelieu wing, which contain some of the Louvre’s most ancient pieces. Bible students, amateur archaeologists, and Iraq War vets may find the collection especially interesting.

Saddam Hussein was only the latest iron-fisted, palace-building conqueror to fall in the long history of the region that roughly corresponds with modern Iraq. Its origins stretch back to the dawn of time. Civilization began 6,000 years ago between the Tigris and Euphrates rivers, in the area called the Fertile Crescent.

In the Richelieu wing, you can quickly sweep through 2,000 years of this area’s ancient history, enjoying some of the Louvre’s biggest and oldest artifacts. See how each new civilization toppled the previous one—pulling down its statues, destroying its palaces, looting its cultural heritage, and replacing it with victory monuments of its own...only to be toppled again by the next wave of history.

The iconoclasm continues to this day, as Islamist militants vandalized ancient artifacts at Nineveh and elsewhere—making the Louvre’s collection all that much more priceless. It’s interesting to note that while Westerners make pilgrimages to the Greek and Renaissance sections of the Louvre, visitors from the Middle East are drawn to this part of the museum’s collection.

• From under the pyramid, enter the Richelieu wing. Show your ticket, then take the first right. Go up one flight of stairs and one escalator to the ground floor (rez-de-chaussée), where you’ll find the Near Eastern antiquities. Walk straight off the escalator, enter Salle 1-a (Mesopotamie Archaïque), and come face-to-face with fragments of the broken...

As old as the pyramids, this Sumerian stela (ceremonial stone pillar) is thought to be the world’s oldest surviving historical document. Its images and words record the battle between the city of Lagash (100 miles north of modern Basra) and its neighboring archrival, Umma.

Circle around the partition to the other side of the stela. “Read” the stela from top to bottom. Top level: Behind a wall of shields, a phalanx of helmeted soldiers advances, trampling the enemy underfoot. They pile the corpses (right), and vultures swoop down from above to pluck the remains. Middle level: Bearded King Eannatum waves to the crowd from his chariot in the victory parade. Bottom level: They dig a mass grave—one of 20 for the 36,000 enemies dead—while a priest (top of the fragment, in a skirt) gives thanks to the gods. A tethered ox (see his big head tied to a stake) is about to become a burnt sacrifice.

The inscription on the stela is in cuneiform, the world’s first written language, invented by the Sumerians.

• Continue into Salle 1-b, with the blissful...

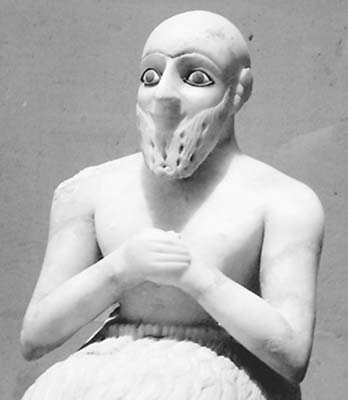

Bald, bearded, blue-eyed Ebih-il (his name is inscribed on his shoulder) sits in his fleece skirt, folds his hands reverently across his chest, and gazes rapturously into space, dreaming of...Ishtar. A high-ranking dignitary, Ebih-il placed this statue of himself in the goddess Ishtar’s temple to declare his perpetual devotion to her.

Ishtar was the chief goddess of many Middle Eastern peoples. As goddess of both love and war, she was a favorite of horny soldiers. She was a giver of life (this statue is dedicated “to Ishtar the virile”), yet also miraculously a virgin. She was also a great hunter with bow and arrow, and a great lover (“Her lips are sweet...her figure is beautiful, her eyes are brilliant...women and men adore her,” sang the Hymn to Ishtar, c. 1600 B.C.).

Ebih-il adores her eternally with his eyes made of seashells and lapis lazuli. The smile on his face reflects the pleasure the goddess has just given him, perhaps through one of the sacred prostitutes who resided in Ishtar’s temple.

• Go up the five steps behind Ebih-il, and turn left into Salle 2, containing a dozen statues of the same man.

Gudea (r. 2141-2122 B.C.), in his wool stocking cap (actually a royal turban), folds his hands and prays to the gods to save his people from invading barbarians. One of Sumeria’s last great rulers, the peaceful and pious Gudea (his name means “the destined”) rebuilt temples (where these statues once stood) to thank the gods for their help.

• Exit Salle 2 at the far end and enter Salle 3, with the large black stela of Hammurabi.

King Hammurabi (r. c. 1792-1750 B.C.) extended the reach of the great Babylonian empire, which joined Sumer and Akkad (stretching from modern-day Baghdad to the Persian Gulf). He proclaimed 282 laws, all inscribed on this eight-foot black basalt stela—one of the first formal legal documents, four centuries before the Ten Commandments. Stelas such as this likely dotted Hammurabi’s empire, and this one may have stood in Babylon before being moved to Susa, Iran.

At the top of the stela, Hammurabi (standing and wearing Gudea’s hat of kingship) receives the scepter of judgment from the god of justice and the sun, who radiates flames from his shoulders. The inscription begins, “When Anu the Sublime...called me, Hammurabi, by name...I did right, and brought about the well-being of the oppressed.”

Next come the laws, scratched in cuneiform down the length of the stela, some 3,500 lines reading right to left. The laws cover very specific situations, everything from lying, theft, and trade to marriage and medical malpractice. The legal innovation was the immediate retribution for wrongdoing, often with poetic justice.

#1: If any man ensnares another falsely, he shall be put to death.

#57: If your sheep graze another man’s land, you must repay 20 gur of grain.

#129: If a couple is caught in adultery, they shall both be tied up and thrown in the water.

#137: If you divorce your wife, you must pay alimony and child support.

#218: A surgeon who bungles an operation shall have his hands cut off.

#282: If a slave shall say, “You are not my master,” the master can cut off the slave’s ear.

The most quoted laws—summing up the spirit of ancient Near Eastern justice—are #196 (“If a man put out the eye of another man, his eye shall be put out”) and #200 (“a tooth for a tooth”).

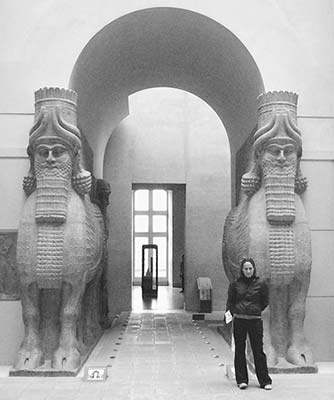

• Facing the stela, veer ahead to the left and enter the large Salle 4, dominated by colossal winged bulls with human heads. These sculptures—including five winged bulls and many relief panels along the walls—are from the...

Sargon II, the Assyrian king (r. 721-705 B.C.), spared no expense on his palace (see various reconstructions of the palace on plaques around the room). In Assyrian society, the palace of the king—not the temple of the gods—was the focus of life, and each ruler demonstrated his authority with large residences.

Sargon II actually built a whole new city for his palace, just north of the traditional capital of Nineveh (modern-day Mosul). He called it Dur Sharrukin (“Sargonburg”), and the city’s vast dimensions were 4,000 cubits by—oh, excuse me—it covered about 150 football fields pieced together. The whole city was built on a raised, artificial mound, and the 25-acre palace itself sat even higher, surrounded by walls, with courtyards, temples, the king’s residence, and a wedding cake-shaped temple (called a ziggurat) dedicated to the god Sin.

• Start with the two big bulls supporting a (reconstructed) arch.

These 30-ton, 14-foot alabaster bulls with human faces once guarded the entrance to the throne room of Sargon II. A visitor to the palace back then could have looked over the bulls’ heads and seen a 15-story ziggurat (stepped-pyramid temple) towering overhead. The winged bulls were guardian spirits, warding off demons and intimidating liberals.

Between their legs are cuneiform inscriptions such as: “I, Sargon, King of the Universe, built palaces for my royal residence...I had winged bulls with human heads carved from great blocks of mountain stone, and I placed them at the doors facing the four winds as powerful divine guardians...My creation amazed all who gazed upon it.”

• We’ll see a few relief panels from the palace, working counterclockwise around the room. Start with the panel just to the left of the two big bulls (as you face them). Find the bearded, earringed man in whose image the bulls were made.

Sargon II, wearing a fez-like crown with a cone on the top and straps down the back, cradles his scepter and raises his staff to receive a foreign ambassador who has come to pay tribute. Sargon II controlled a vast empire, consisting of modern-day Iraq and extending westward to the Mediterranean and Egypt.

Before becoming emperor, Sargon II was a conquering general who invaded Israel (2 Kings 17:1-6). After a three-year siege, he took Jerusalem and deported much of the population, inspiring the legends of the “Lost” Ten Tribes. The prophet Isaiah saw him as God’s tool to punish the sinful Israelites, “to seize loot and snatch plunder, and to trample them down like mud in the streets” (Isaiah 10:6).

• On the wall to the left of Sargon are four panels depicting the...

Boats carry the finest quality logs for Sargon II’s palace, crossing a wavy sea populated with fish, turtles, crabs, and mermen. The transport process is described in the Bible (1 Kings 5:9): “My men will haul them down from Lebanon to the sea, and I will float them in rafts to the place you specify.”

• Continue counterclockwise around the room—past more big, winged animals, past the huge hero, Gilgamesh, crushing a lion—until you reach more relief panels. These depict...

The brown, eroded gypsum panels we see here were originally painted and varnished. Placed side by side, they would have stretched over a mile. The panels read like a comic strip, showing the king’s men parading in to serve him.

First, soldiers sheathe their swords and fold their hands reverently. A winged spirit prepares them to enter the king’s presence by shaking a pinecone to anoint them with holy perfume. Next, servants hurry to the throne room with the king’s dinner, carrying his table, chair, and bowl. Other servants ready the king’s horses and chariots. They all proceed forward, ready to serve their master—the all-powerful ruler of the civilized world.

Sargon II’s palace remained unfinished and was later burned and buried. Sargon’s great Assyrian empire dissolved over the next few generations. When the Babylonians revolted and conquered their northern neighbors (612 B.C.), the whole Middle East applauded. As the Bible put it: “Nineveh is in ruins—who will mourn for her?... Everyone who hears the news claps his hands at your fall, for who has not felt your endless cruelty?” (Nahum 3:7, 19).

The new capital was Babylon (50 miles south of modern Baghdad), ruled by King Nebuchadnezzar, who conquered Judea (586 B.C., the Bible’s “Babylonian Captivity”) and built a palace with the Hanging Gardens, one of the Seven Wonders of the World.

Over the succeeding centuries, Babylon/Baghdad fell to Persians (539 B.C.), Greeks (Alexander the Great, 331 B.C.), Persians again (second century B.C.), Arab Muslims (A.D. 634), Mongol hordes (Genghis Khan’s grandson, 1258), Iranians (1502), Ottoman Turks (1535), British-controlled kings (1921), and military regimes (1958), the most recent headed by Saddam Hussein (1979).

After toppling Saddam Hussein in 2003, President George W. Bush declared, “Mission accomplished!” After five thousand years of invasions, violence, and regime change, Iraq was finally...well, maybe not.