A view from the deep – introducing the fish

A year after Charles Darwin returned from his voyage on HMS Beagle, in July 1837, he picked up a notebook and sketched a small stick-tree. He labelled the divided branches around the crown A, B, C and D, and next to it wrote the words ‘I think’.

It would be another 22 years before he published On the Origin of Species and yet that twiggy sketch seems to have been Darwin’s first attempt at visualising the pathway of evolution. The notion of a tree of life had been around for a long time, but Darwin was the first to propose a clear idea of how it all came about.

Fast forward to 2016, and a paper in the journal Nature Microbiology announced a ‘New view of the tree of life’. It’s based on gene sequences, and brings into play dozens of groups of bacteria and other microbes whose existence until recently went completely undetected. It’s a far cry from Darwin’s modest twigs, and doesn’t look like a tree so much as a splayed frond of seaweed. Nevertheless, both trees are based on the same essential idea: that life gave rise to other life, and all living things are related.

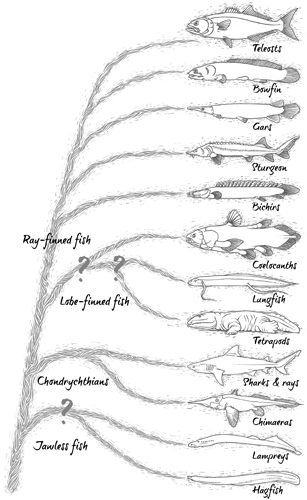

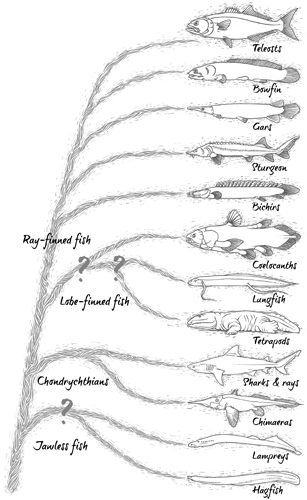

When reading an evolutionary tree, the main points to remember are that the most ancient life forms are located at the bottom and give rise via natural selection to other lineages that split off and occupy their own branches. Also, the points where branches join the main trunk represent a common ancestor shared by the two lineages that split apart. On a human family tree, this is the equivalent of an uncle or a grandparent shared by cousins. In evolutionary studies, we rarely know what those ancestors looked like, or precisely when they existed. Nor indeed were the ancestors single organisms, but a population that split and gradually evolved into separate species.

Fish evolutionary tree depicting likely relationships between 12 living groups.

If we zero in on part of the tree of life where fish are stationed, there’s a thicket of branches. An ultimate version of the fish evolutionary tree would include all 30,000 species. Even the tree in Nelson’s Fishes of the World spreads over several pages, depicting seven superclasses and 62 orders of fish. But fear not. To lead us through the immense diversity of fish life we don’t need such a complex tree. We’ll do just fine with a no-frills version with 12 branches and branchlets. That may seem like a drastic prune, but these 12 groups represent the essential divisions among the fish, and they’ll make sure we don’t miss anything significant.

We’ll browse this tree not as if we were climbing an actual tree, starting from the ground and working our way upwards and outwards, towards the ends of dividing branches, but as if we’ve already reached the outermost boughs and are now clambering back towards terra firma. The species we’ll meet in these 12 groups are by and large still alive today (evolutionary trees can include extinct members, too, but we’ll get to those later) and, as we go, we’ll pass junctions that represent increasingly ancient ancestors, shared by the branches above. In this way our exploration of the fish tree becomes a journey back through time. It means that as we move down the tree we’ll encounter living fish groups with a direct lineage tracing back to ancestors that lived further and further in the past. And it means that we begin our journey with the latest fish group to split off from the others, one that also happens to be the most important today.

Think of a fish – any fish – and the chances are that swimming around in your mind is a teleost. This is the first group we encounter on the fish’s evolutionary tree, and it’s overwhelmingly the biggest. Teleosts account for roughly 96 per cent of all known fish species,1 so it’s no surprise that in this group we see the greatest diversity in the ways fish look, the things they do and the places they live.

Wherever there’s water, there you can spot teleosts: Goldfish swim in garden ponds; gobies climb Hawaiian waterfalls, clinging to rocks with their lips; high in the Himalayan mountains are giant catfish that grow to the size of an adult human, and may occasionally eat one; silver shoals of anchovies, sardines and herring spiral through open seas, chased by master hunters, the swordfish, sailfish, tuna and Wahoo.2

There are teleosts living in glacial waters that swirl around Antarctica, the coldest ocean on the planet. Icefish survive in sub-zero temperatures and for years biologists guessed they must have some strategy to stop themselves freezing. The ocean itself doesn’t freeze here because it’s very salty, but living tissues can’t tolerate such high salt levels. The fish had some other secret for staying supple. In the 1960s, Arthur DeVries, then at Stanford University in California, found molecules circulating in the icefish’s bloodstream, called glycoproteins, which halt the growth of ice crystals. He had uncovered a fish version of antifreeze. Similar molecules have since been isolated from many other teleosts. Sculpins and flounders, herring and cod all have genes for making their own antifreezes, which they can switch on when the temperature drops.

Teleosts are also the deepest-living of all the fish. Down in the abyss, miles beneath the waves, are tripod spiderfish that perch on the seabed with three long fins and wait for prey to drift by. Further down still, cusk eels and snailfish vie to be not only the deepest fish but the deepest vertebrates of all. Exactly which group wins is frankly splitting hairs, since both have been spotted around eight kilometres (five miles) down, not quite at the bottom of the Marianas Trench, the oceans’ deepest point. Both types of fish have soft, transparent skin and small, deep-set eyes that probably don’t work especially well. Some cusk eels have such tiny eyes they’ve been named ‘faceless fish’.

Even where there’s very little water, teleosts still find a way to survive. In the middle of America’s Death Valley, one of the hottest deserts on the planet, Devil’s Hole Pupfish occupy a single underground lake, in a limestone cave. Since scientists started doing head counts in the 1970s, the number of these little blue fish has ranged from 35 to just over 500. At the latest count there were 115, giving the Devil’s Hole Pupfish the dubious honour of being the rarest fish in the world. In April 2016, a group of drunken men broke into the pupfish’s fenced-off cave, splashed about in the water, vomited and trod on several fish, killing at least one. To add insult to injury, they left behind a pair of underpants.

Teleosts can survive a lack of water by being mobile. When Walking Catfish from Southeast Asia find themselves trapped in a shrinking pond they simply trot off, hauling themselves overland on their fins, to find somewhere wetter. Mangrove killifish survive for months with no water at all, absorbing oxygen through their skin, and hiding in tree holes, empty crab burrows and coconut shells. When they get too hot, they leap into the air to cool down.

The biggest teleosts of all are sunfish, their bodies flattened discs up to three metres (10ft) across and weighing more than two tonnes (5,000lb).3 They’ve been nicknamed ‘swimming heads’; they have no tails, and swim by flicking a tall dorsal and anal fin from side to side. Their common name, sunfish, comes from their habit of sunbathing on their sides at the sea surface. This added to their reputation as sedate, loafing animals, but in 2015 Itsumi Nakamura and colleagues at the University of Tokyo fixed temperature probes, accelerometers and little cameras to sunfish and discovered they make energetic dives into deep, cold waters chasing jellyfish, then they lie in the sun afterwards to warm up.

The name teleost refers to the fact that they perch on this outermost branch of the fish evolutionary tree. They’re the ones with ‘perfect bones’ (from Ancient Greek words teleios meaning perfect or full grown, and osteon meaning bone), although there’s nothing inherently perfect about them; they just happen to occupy the branch that split off most recently.

All of these various fish are collected together because they share a set of characteristics. Their ‘perfect’ bones are less dense than their ancestors’, with internal cross-struts that make them strong but light. Their backbone runs all along the body and comes to an end at a region just before the tail called the caudal peduncle. Here the arrangement of bones is such that their tails are stiffened compared to their more distant ancestors.4 This generally makes teleosts good swimmers; they propel themselves with powerful beats of their tail without needing to swing their whole body from side to side.

Teleosts are generally covered in ultra-thin, lightweight scales, comprised of a composite of collagen and hydroxyapatite, the calcium-based mineral that makes up much of human bones. Scales grow in overlapping rows from head to tail, like roof tiles, giving teleosts tough, flexible suits of armour.

There’s also a certain arrangement of bones in teleost jaws that allows them to fling their mouths forwards to suck in prey. This has helped them diversify their diet and means they can eat just about anything; they’ll nibble on plankton, graze on seaweed, eat each other (dead or alive), munch leaves, slurp dirt and chew seeds. The rest of the fish we’ll meet are much fussier – most of them are strict carnivores.

Within the teleosts are dozens of sub-groups. There are some 1,600 species of piranhas, tetras, characins and pencilfish, more than 3,000 carp, minnows and loaches, and a similar number of catfish, including mountain, velvet and bumblebee catfish. There are over 550 cod, 700 flatfish and another 800 eels.

Two of the biggest teleost sub-groups bring together many of the cast of animals that feature in this book. One rambling group (the Percoidea) is home to ponyfish that glow in the dark, archerfish that shoot water, leaf-fish that pretend not to be fish and croakers that make a racket. Many coral-reef fish are here too: groupers, butterflyfish, angelfish, goatfish, snappers and dottybacks.

Wrasse and damselfish, parrotfish and rabbitfish – named respectively for their beaky and bucktoothed dentitions – join together in another large group (the Labroidei) along with cichlids, which inhabit freshwaters worldwide but most famously as a flock of species in the Great Lakes of Africa. Some time between two and 10 million years ago a new split opened up in the Earth’s crust, along Africa’s Rift Valley, and filled with water to form Lakes Malawi, Victoria and Tanganyika. Cichlids were among the first fish to move in, and subsequently they’ve evolved into some 1,700 endemic species found nowhere else on the planet. Some of them evolved fast and furiously. It’s thought Lake Victoria was completely dry 12,500 years ago, which means around 500 endemic species must have arisen since then.

With so many perfect-boned fish, it’s perhaps easier to point out which animals you might spot that are something other than teleosts. To meet them we need to move on to the next branch down the fish evolutionary tree.

Take a look in a quiet backwater of a river in the eastern United States, perhaps the St Lawrence or the Mississippi, and you might catch sight of a lone evolutionary survivor. You’ll probably need to peer closely among plant roots or under logs to find one. It is cylindrical in shape, dappled olive brown in colour and usually around 50cm (20in) long when fully grown. If there’s a spot on its tail, with an orange ring around it, then you have a young male. It can swim forwards and backwards with equal ease, undulating the dorsal fin that runs all along its back.

This is a Bowfin, the teleosts’ closet living relative. Around 200 million years ago, in the late Triassic, bowfins shared a common ancestor with the teleosts. They went on to flourish in marine and freshwaters from America to Europe, Asia to Africa. Now, though, you’ll only see a single Bowfin species in the margins of rivers, lakes and swamps in North America.

A mix of body parts places the Bowfin in its own separate group (the Amiiformes). They share some characteristics with teleosts, such as gills for extracting oxygen from water; a gas-filled balloon known as the swim bladder, which acts like an internal flotation device; and a series of fluid-filled pores and canals called the lateral line, which detect movements and vibrations in the water (more on those later). Bowfins also have a handful of other, more unusual features, including the way they use their swim bladder not just to float around but to breathe dry air. This is more reminiscent of fish further down the evolutionary tree, including the gars, which lie on the next branch down.

In the shallow, weedy rivers and lakes of North America, as well as Bowfins, you might spot a member of another group of fish survivors that once lived worldwide. There are seven species of gar, which share a common ancestor with Bowfins that lived roughly 260 million years ago. Gars are covered in interlocking, glassy scales, which Native Americans traditionally used to cover breastplates and to make tips for their arrows. The most notorious gar, and the biggest, is the Alligator Gar. With a long snout and two nostrils at the end, this two-metre (6.5ft) fish looks distinctly reptilian. The double rows of teeth inside its mouth are an instant giveaway that it’s not a real alligator, but from a distance it can still have people easily fooled. In 2010, dozens of Alligator Gars were spotted swimming in a lake in Hong Kong, a long way from their original American homes. Locals panicked, assuming they were true crocodilians, and officials quickly came to take them away. It’s assumed the wandering gars had been set free by aquarium-keepers who weren’t prepared for the enormous size their pets would reach.

Eggs are the most celebrated parts of the fish we encounter next on our journey down the fish evolutionary tree. On the fourth branch down are 27 living species of sturgeon. Most of them haven’t changed a whole lot in appearance since their ancestors shared Jurassic seas with ichthyosaurs and plesiosaurs, and maybe sensed the footfall of dinosaurs tromping the edges of brackish lagoons. Instead of scales sturgeons have rows of spiky plates, called scutes; they have fleshy, upturned snouts, speckled in electro-sensitive pores, with four whiskers hanging down.

Sturgeon are northern-hemisphere residents. If you’re lucky you might spot them in the same American waters as Bowfin and gars; they also live across Europe and Asia, in rivers and lakes from the Atlantic to the Pacific. Throughout their range, sturgeons haven’t been doing so well, ever since people developed a taste for their eggs, known as caviar. Favoured species include Kalugas from the Amur River, which rises in the mountains of northeast China and flows to the Sea of Okhotsk in the north Pacific. Sevruga Sturgeons, from rivers draining into the Caspian, Azov and Black Seas in eastern Europe and Asia, are also prized for their eggs. In the same waters swim Beluga Sturgeon, whose eggs are considered the finest caviar, commanding the highest prices. An individual female can grow up to eight metres (26ft) long, bigger than her mammalian namesake the Beluga Whale; her ovaries can account for a quarter of her body weight, and she’ll lay millions of eggs in a single clutch. A record-breaking Beluga was killed in Russia in 1924, weighing more than 1.2 tonnes and with 245kg (540lb) caviar inside her; try buying that much caviar on the open market today and it would set you back at least a million pounds, perhaps two.

The demand for caviar is one reason why, in 2010, sturgeon were declared the most threatened group of animals in the world, with 23 out of 27 species at risk of extinction.5 Syr Darya Shovelnose Sturgeons, with long whip-like tails, haven’t been seen alive since the 1960s. Beluga Sturgeon are considered to be critically endangered. The only species you stand a good chance of encountering is the White Sturgeon from the US Pacific coast. At up to six metres (20ft) long, they’re the biggest freshwater fish in North America, although they more usually reach only half that size and actually spend more of their time at sea, close to shore, before swimming inland to spawn.

Dams blocking the sturgeons’ paths as they try to migrate to their spawning grounds add to their modern-day troubles, as do the increasingly polluted waters they swim through. And in general, sturgeon are poorly equipped for dealing with any of these problems. They can take decades to reach maturity, and even then females only spawn once every five years or so. Compared to faster-growing species, sturgeon populations don’t recover quickly. On the plus side, sturgeon can live for a century or more, which means that if a few remaining individuals are wandering around in the wild, there’s a chance they might eventually find each other and successfully spawn.

In even worse shape are two close relatives of sturgeons, also found on this same evolutionary branch (the Acipenseriformes). One lives in America, the other in China – or at least it did. Scientists fear that the Chinese Paddlefish is now extinct. It was last seen alive in 2003. That’s despite a team of biologists spending three years, up to 2009, looking for it along the Yangtze River, from high in the Tibetan plateau all the way to Shanghai. All they came back with were two sonar readings that detected lumps in the water of around the right size that could, maybe, have been paddlefish.

American Paddlefish, also known as Spoonbill Catfish, are doing a little better across their range in the lakes and braided channels of the Mississippi basin. A third of their two-metre (6.5ft) long body consists of a broad, flattened snout (which looks a bit like a paddle, hence their name), supported by a lacy network of star-shaped bones that lie beneath their scaleless skin. It was only recently that scientists worked out the purpose of this odd protuberance. The paddle is covered in dimples equipped with sensory receptors that detect weak electric fields. As a paddlefish sweeps its snout through the water, it homes in on pulses from wriggling water fleas close by and swoops in, its mouth wide open like a trapdoor.

Efforts are underway in North America to restore paddlefish to their former glory. They used to have a much wider range, throughout the Great Lakes and in at least four states where they’re no longer found. Many reservoirs are stocked with farm-reared paddlefish, partly so anglers can catch them, but these are located in spots where there’s nowhere for these fish to spawn. For that they need fast-flowing water and clean gravel. Many of America’s paddlefish are just old fish, getting older.

Search for a missing link

Taking a step further down the fish evolutionary tree, we meet the first in a series of fish that for a long time had taxonomists baffled. Bichirs6 look like small snakes with smiles. There are 12 species, known as dragonfish in the pet trade, and to see one in the wild you’ll have to go and look in rivers and swamps in Africa. They’re covered in shiny scales and have a long dorsal fin snipped into sections, known as finlets; they swim by fluttering their wide, fan-like pectoral fins. Bichirs mainly breathe air through a pair of lungs, inhaling through their mouth and exhaling through holes called spiracles on the top of their head. They have rudimentary gills but in stagnant water, if they don’t have access to the surface to breathe air, they drown.

When they were first discovered in the River Nile in 1802, anatomists had never seen such an odd mixture of features and they sparked an important question: are bichirs a link between fish and amphibians?

The lack of intermediate stages between different animal groups was something Charles Darwin contemplated at great length. Finding these apparently ‘missing links’, whether in fossils or living creatures, would support his theory of species giving rise to other species, and help map out the shape of the tree of life. Of particular interest were the links between vertebrates that live in water and those on land, the tetrapods, and the question of how exactly our ancestors adapted to a terrestrial way of life.

Towards the end of the 19th century, it became popular to study animal embryos to gain clues about the pathways of evolution. The idea was that animal groups look distinct at a microscopic level during the first steps of life, as fertilised eggs divide into a bundles of cells. To work out whether bichirs were fish or amphibians, or somewhere in between the two, scientists were convinced they needed a bichir embryo – something that wasn’t easy to come by. These animals live in places like the Congo and Nile basins, which can still be difficult and dangerous to get to today. But that didn’t put off two men who, more than a century ago, were determined to fill in this zoological gap.

One was an Englishman, John Budgett. As a young boy, he was already a keen zoologist. He kept all sorts of pets at home and built a small museum, filled with stuffed animals and skeletons he prepared himself, including a cow, a deer and his family’s Shetland pony. He frequently visited his local zoo to check on the health of any sick animals, hoping for new specimens.

In 1894, Budgett went to Cambridge University to study zoology, but he was soon lured further afield. His first taste of exploration came in 1896 when he accompanied John Graham Kerr, another Cambridge student, on a year-long expedition to Paraguay to collect lungfish (a fish group which we’ll meet shortly), in swampy, insect-infested conditions that Budgett would become familiar with. Kerr and Budgett found their first lungfish without effort, when locals served some up for their first dinner. Kerr later wrote that the lungfish had been ‘most tasty’. Returning from Paraguay, Budgett scraped through his final year exams in Cambridge and made plans for his own expedition, this time to find bichirs.

Meanwhile, apparently unbeknown to Budgett, another bichir hunter set out to find embryos of this possible missing link. In 1898, Nathan Harrington from Columbia University in New York spent four months in Egypt, scouring the Nile for bichirs. He found mature adults and tried many times to artificially fertilise their eggs – taking eggs from a female and bathing them in a male’s sperm – but without success. On a return trip to Egypt, Harrington was overcome by fever and in 1899, aged 29, he died.

John Budgett had thought of going to the Nile but on a friend’s recommendation went instead in October 1898 to the other side of the African continent, to the small nation of The Gambia, at the time a British colony. He spent eight months far inland along the River Gambia, much of it in pouring rain, undertaking the same fruitless research as Harrington. At least Budgett learned much about catching these unusual, nocturnal animals, and he pinpointed their breeding season. Now he knew exactly when to return to Africa.

At the end of that first trip, Budgett brought two living bichirs back to England and they lived on for another three years, carefully tended by his brother, Herbert. The captive bichirs put on courtship displays, but never produced any young.

In 1900, undeterred by repeated bouts of malaria picked up during his travels, Budgett went back to The Gambia, this time at the height of the rainy season in June when he was sure the bichirs should be mating. Yet again, despite three months of searching, he didn’t find any embryos. He tried again, in 1902, this time in eastern Africa, in Uganda and Kenya, but once again he came home empty handed.

Then, the following year, Budgett’s luck finally began to change. He sailed back to West Africa and travelled by paddle steamer up the River Niger. The going was hard. ‘It rains almost continuously, everything is mildew and rust,’ Budgett wrote in his diary. ‘The depression of this vapour-bath is almost unbearable.’

Finally, after four gruelling expeditions, Budgett found what he had been searching for, but it came at great cost. In Nigeria, on 26 August 1903, he successfully fertilised bichir eggs and watched down his microscope as the transparent spheres began to split and cleave into living balls of cells. Two days later he sent a letter to his old friend, Graham Kerr, telling him that the resulting embryos were ‘astoundingly frog-like’. They were complete (meaning the whole eggs divides and not just part of it) and equal (the egg splits into cells of equal size) and the bundle began to fold in a way seen in frog embryos. But by the time Budgett prepared to head home with his prized preserved embryos, he was again suffering from malaria.

Back in Cambridge, on 9 January 1904, having just finished a series of intricate bichir embryo drawings, Budgett showed the first signs of blackwater fever, a deadly complication of malaria in which red blood cells burst in the bloodstream. Ten days later, on the day he was due to present his findings to the Zoological Society of London, John Budgett died.

A collection of preserved eggs and embryos and some detailed drawings were all that Budgett left behind to mark his ultimately fatal quest. There was no manuscript or notes. Four years later it was another scientist, Edwin Stephen Goodrich from Oxford University, who gathered together everything then known about bichirs and announced that they are not the direct ancestors of frogs – just very strange fish. Many of their peculiar features evolved separately along their own branch of the fish evolutionary tree, including their frog-like early development and their ability to regrow a severed limb.

Much later, in 1996, DNA sequencing confirmed that bichirs are not a missing link between fish and frogs, but they are the earliest division of the ray-finned fish, fish that have fins made up of spines sticking up from the base with skin stretched between them.7 Interest in bichirs and their embryos faded but ichthyologists remained preoccupied for much longer with another enigmatic group that is situated on the next branch down the fish evolutionary tree.

Lungfish have long been mistaken for other things. A fossilised lungfish tooth was described in 1811 as a piece of tortoise shell. In 1833, Swiss scientist Louis Agassiz, probably the greatest ever authority on ancient fish, identified another lungfish fossil as a type of shark (he later changed his mind). When the first living lungfish showed up in 1836, at the mouth of the Amazon River, experts back in Europe thought it was a reptile, due to the snippet of lung tissue still hanging to the gutted specimen. The following year a different variety was discovered in Africa and, based on the structure of its heart, it was declared amphibian.

For another three decades, the lungfish debate rumbled on, with experts picking and choosing sides. Richard Owen, famous for founding London’s Natural History Museum and coining the word ‘dinosaur’, was utterly convinced of the fishy nature of lungfish, pushing them away from reptiles. ‘Not by its gills, not by its air bladders … nor its extremities nor its skin nor its eyes nor its ears,’ he wrote, ‘but simply by its nose.’ He was sure that a reptile’s nose has two openings, while a fish merely has a blind-ended sac, something he thought he saw in lungfish.8

Today all six known lungfish species are confined to slow-moving rivers, swamps and freshwater pools in Africa, South America and Australia. They all have elongated, eely bodies, some up to two metres (6.5ft) long, and some have pelvic and pectoral fins like strings of spaghetti. Only the Australian Lungfish has gills that still work, while all the others rely entirely on their paired lungs for oxygen. So, like bichirs, it’s quite possible for these fish to drown. It does mean, however, that they can survive without water. In Africa and South America, lungfish can tough out long dry seasons by chewing themselves a burrow in the mud, filling it with mucus, and curling up inside; they can survive this way for up to four years. When finally the rains return, the lungfish emerge from the mud and eat whatever they come across, often another sleepy lungfish who has also just woken up. And they can live for a long time – at least in captivity. A lungfish called Granddad was taken from the wild in Australia in 1933 and kept in the Chicago Aquarium, where he died in 2017.

For a while it was thought that there might be a seventh lungfish. A few years after the first Australian species was found, another came to light in northern Queensland in 1872 when Karl Staiger, director of the Brisbane Museum, ate one for breakfast. The lungfish was 45cm (17in) long, covered in large scales, and had a flattened snout, curiously similar to that of the platypus. Staiger paused, fork in hand, just long enough for someone to sketch the strange fish and write a few notes, before he tucked in. The notes and drawing went to French naturalist Francis de Castelnau, who named the new species Ompax spatuloides and likened it to the Alligator Gar of North America but decided it was a new type of lungfish. A second specimen was never found, but the strange creature did emerge one more time, in a letter sent to a Sydney newspaper almost 60 years later. The truth was revealed that Staiger’s meal had in fact been a hoax, stitched together from a mullet’s body, an eel’s tail, a platypus’s bill and the head of an Australian lungfish.

Up to the present day, lungfish have remained caught in the cross-winds of research trends, batted from place to place in fossil and evolutionary studies, embryology, molecular sequencing and more. Still there are matters undecided. One question lungfish pose is whether fish first evolved lungs or swim bladders. Did they evolve lungs first, organs rich with blood vessels and permeable to gases, then later co-opt them as airtight flotation devices? Are lungs modified swim bladders, or did the two organs arise independently?

In embryos, swim bladders and lungs both develop from a pocket in the gut. No fish have both organs so, like Clark Kent and Superman, it seems likely that one is a version of the other.

You may already be thinking of swim bladders as a distinctly fishy characteristic, a feature of all the fish we’ve met so far. However, lungfish don’t have them, suggesting that lungs could in fact have been around for the longest.

Research from a few years ago backed up this idea, when Sarah Longo from Cornell University in New York took a lungfish, a paddlefish, a sturgeon, a Bowfin, a gar and a bichir and put them one by one inside a CT scanner.9 This let her scrutinise the detailed arrangement of their blood vessels, revealing key similarities between the fish with lungs (the lungfish, Bowfin and bichir) and those with swim bladders (the sturgeon, gar and paddlefish).10 Longo found that all these organs are hooked up to a pair of pulmonary arteries, the same vessel that transports blood from your heart to your lungs. In sturgeon and gars these vessels are vestigial and hadn’t been detected before. Discovering that their swim bladders are in fact connected to the same blood vessels as lungs in more ancient fish provides another strand of evidence that lungs did indeed evolve first and were later adapted to form the swim bladder.

Lungfish share this branch of the fish evolutionary tree with two close living relatives. This trio are together known as lobe-finned fish (or sarcopterygians) and they differ from ray-finned fish chiefly in that they have fleshy fins that join via a bony connection to the backbone at the hip and shoulder. As we’ll see, it’s not exactly clear which group split off on the first twig along this branch, but all of them are without doubt important in the history of fish.

Coelacanths11 are perhaps most famous today as fish that were thought to have been extinct for millions of years. That was until 1938, when a South African biologist, Marjorie Courtenay-Latimer, was paying one of her regular visits to the local docks to see what fishermen had trawled up, when she spotted something strange. It was a huge, mauve fish with iridescent silver markings, a tail with three lobes and four large, fleshy fins. She carted off the two-metre (6.5ft) fish in a wheelbarrow to find somewhere to get its remains preserved. Her finding was as unexpected and dramatic as a living Velociraptor ambling out of a far-flung desert. Eventually, South African ichthyologist J. L. B. Smith created an entire new genus for the fish and named it after her – Latimeria.

It’s well established now that at least two coelacanth species inhabit deep, sunken volcanic slopes pocked with caves. Marjorie’s species lives around the Comoros Islands, off the coasts of Madagascar, Mozambique and South Africa, while a second species was spotted in 1998 by another biologist, Mark Erdman, in another fish market, this time in Indonesia. These are the only known descendants of at least 80 coelacanth species that once roamed oceans and freshwaters around the world.12

Since their rediscovery, more details of coelacanth’s lives have come to light. Females produce enormous eggs, bigger than baseballs, which hatch and develop inside them for up to three years before being born (a process known as ovoviviparity). Adult coelacanths spend their days huddled together in caves down at 250m (820 ft); it’s no wonder they stayed hidden from scientists for so long. At night, they venture deeper, to 500m (1,640ft), to hunt for fish and squid. Initially it was thought they might stalk the seabed on their fleshy fins, but film footage shot from mini submarines has shown them drifting along, sculling with their four paired fins in a diagonal pattern, the same way a lizard moves its legs. But coelacanths were not the direct ancestors of amphibians, or reptiles, or anything else with four legs. For that we need to look at another group of lobe-finned fish and another of the lungfish’s close relatives.

Back in the Devonian, around 380 million years ago, coelacanths and lungfish shared the seas with another group of lobe-finned fish, a renegade troupe called the tetrapodomorphs.13 Some looked similar to lungfish and paddled around open water. Others looked more like huge salamanders; in place of fins they had legs and arms, hands and feet. They clambered about boggy, marshy plants and could have lifted up their heads, looked over their shoulders and waved eight little fingers.

All these animals, now long gone, began to show themselves to palaeontologists through a series of remarkable fossil finds. The most recent was Tiktaalik, found in 2004 in Ellesmere Island in far northern Canada. It looked like a cross between a lungfish and a small crocodile and probably hung about in shallow waters, dashing out to avoid the jaws of huge predatory fish and to snap up insects that were beginning to crawl and scuttle about on land.

Tiktaalik and its Devonian siblings present an elegant sequence of creatures that shifted from a water-based lifestyle to a land-based one. Charles Darwin would have had a field day with them. The arrangement of their bones shows that tetrapod ancestors didn’t evolve all at once but gradually, in stages, as these lobe-finned fish became increasingly adapted to life at watery margins and beyond. Here is the fish-frog, water-land transition that palaeontologists had been searching for.

It’s not known exactly how these transitional fish clambered out of water all those years ago, but recent studies of living fish are providing enticing new clues, including from bichirs, those strange fish that John Budgett devoted his life to finding. While bichirs don’t represent the direct ancestors of tetrapods, they are helping to reveal how extinct fish may have learned to walk.

When water levels recede, bichirs scramble around using their pectoral fins. In 2014, Emily Standen at McGill University in Montreal discovered they can quite quickly improve their walking abilities. She reared some bichirs in a regular, water-filled aquarium tank, and others in a tank with only a thin film of water not deep enough to swim in. After a year, the ones from the drier tank had modified their walking movements compared to the swimmers; they lifted their heads higher, planted their fins more firmly and slipped less often. Not only that, but their bones and muscles changed as they adapted to a perambulatory lifestyle. Similar anatomical reshaping shows up in the fossilised bones of Tiktaalik and its close relatives as they adjusted to life on land. This plasticity in the way fish move hasn’t been demonstrated before; it shows just how flexible they can be, and how fast they can adapt to a changing world.

Whether coelacanths or lungfish are the closest living relatives to tetrapods remains a matter that’s firmly undecided. For decades, taxonomists have been constantly reshuffling these twigs on the tree of life and the wrangling continues today, even with the latest genetic studies. In 2013 the coelacanth genome was sequenced, providing all the pieces of the puzzle, but still the picture remains unclear. Part of the problem lies in the choice of another animal group that’s used for comparison, the so-called outgroup. Using elasmobranchs (sharks and rays) as the outgroup, two separate research teams pushed lungfish into prime position as the sister group to tetrapods. That all seemed well and good until 2016, when another analysis switched things around. A team from Japan swapped in teleosts as the outgroup and consequently put coelacanths back next to the tetrapods. However, in 2017 the same Japanese team had another go, using gars and Bowfins as the outgroup, and this time reinstated the lungfish-tetrapod alliance. This could change once again but, as it stands, those mud-chewing, air-breathing lungfish are the human’s nearest living fish relatives. The ancestors we share with them lived roughly 400 million years ago.

Picking up where we left off and continuing on down the fish evolutionary tree, we reach branch nine out of 12, which split off from the tree at least 450 million years ago. This is the only fish group besides teleosts that contains more than a smattering of living species, and so far they’ve all been waiting patiently in the wings. It’s time to formally welcome the elasmobranchs. The name comes from Greek words meaning ‘beaten metal gills’, but perhaps in the sense of beaten metal being somewhat bendy and elastic, a nod to this group’s soft, cartilaginous skeletons.

There are around a thousand species of elasmobranchs to spot, as they cruise through and sit in the oceans today. Roughly half of them are sharks, the rounded, upright ones with gills on the sides of their bodies. There are familiar sharks, like Great Whites, Salmon Sharks and makos (all types of mackerel shark), Blue Sharks, Oceanic Whitetips and various reef sharks (all requiem sharks). And there are plenty of obscure and little-known species: there are Nervous Sharks, Graceful Sharks, Shy Sharks and Blind Sharks (so-called not because they’re blind, but because they shut their tiny eyes when brought up from the depths into bright light); there are Zebra Sharks and Crocodile Sharks, Grinning and Crying Catsharks, Cow Sharks and Frog Sharks.

The other half of the elasmobranch group are the rays and skates, all of them flattened top to bottom, with gills and mouth on their underside and spiracles on the top to breathe through. There are stingrays, maskrays, electric rays and numbfish, Sapphire Skates and Munchkin Skates, Fanskates and Slime Skates. Some are kite-shaped, others form a perfect circle. Many lie flat on the sea- or riverbed,14 covering most of themselves in sediment except for a pair of eyes sticking up. Some swim through open water, like devil rays and eagle rays, flapping wide pectoral fins like wings.

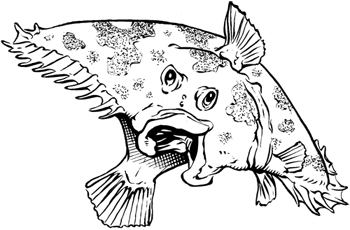

Some sharks are flat and lie on their bellies, like rays. Wobbegongs have dappled skin and mossy beards that blend into reefs, where they sit and wait for prey to wander by. Sawsharks have long snouts fringed in teeth, which they use to root for prey hidden in the seabed. They look a lot like sawfish, but you can tell them apart by locating their gills: sawfish are rays with gills underneath; sawsharks are sharks with gills on the side.

Ever since I started scuba-diving I’d been dying to see a shark. The idea of them never scared me. There’s the thrill of seeing large, wild animals which I rarely come across at home in Britain, except for the occasional deer. I was also determined to prove people wrong, including a few friends and family, who have been led to believe that all sharks are dangerous beasts with voracious appetites for human flesh.

When I went to Belize on a two-month diving expedition I was sure I would finally spot a shark. But after diving two or three times every day on the offshore reefs, I was beginning to lose hope. Then, just a few days before I left, I was finally in the right place at the right time. The wait had made it all the more satisfying, but also at the back of my mind I knew this uncommon encounter was a sure sign of decades of overfishing.

My first shark experience took place while I was on a drift dive, riding a fast current and flying along much faster than normal swimming speed. Ahead I spotted a huge stingray and next to it, snoozing peacefully on the sand, was a Nurse Shark (proof that at least some sharks don’t suffocate when they stop swimming). As I drifted past I had just long enough to see that the shark was bigger than me, it had smooth grey skin, little eyes and a trim moustache dangling from its blunt-ended snout. It lifted its head and, with slow beats of its tail, swam into the current and out of sight.

Nurse Sharks are mostly nocturnal, spending the night rummaging around reefs, hunting for crabs and molluscs hiding in the seabed. Like all elasmobranchs, Nurse Sharks have sensory pores that can detect the weak electric fields generated by living bodies. When they’re not hunting, Nurse Sharks spend a lot of time just sitting. Their inactivity minimises their energy requirements and they can survive when there’s not much food around. Sharks have very low metabolic rates compared to teleosts; they use up less oxygen, burn less fuel and get away with eating a lot less. After a Great White Shark has chewed on the floating carcass of a dead whale it probably won’t have to eat again for another six weeks. A Salmon needs to eat at least four times more than a similar-sized shark. And Nurse Sharks are among the most energy efficient of all the sharks, with the lowest metabolic rate measured so far. A 2016 study revealed that they use about 80 per cent less oxygen per hour, per kilo of body weight, than a fast-paced shark like a Mako.

This bid to save energy is a theme that runs throughout elasmobranch biology, and it’s a key to their great success. They’ve lightened their skeletons, replacing heavy bone with lightweight cartilage, the same rubbery tissue that your nose and ears are made of. Sharks also boost their swimming efficiency with their enormous, oily livers that slow their rate of sinking and help keep them afloat, in a similar way to the teleosts’ swim bladders. A Basking Shark that weighs a tonne in dry air only weighs 3.3kg (7lb) when it’s underwater because of its buoyant liver. In the 20th century, Basking Sharks were hunted for their liver oil, as a source of vitamin A and as a high-grade lubricant for the aviation industry.15 Even today, various species of deep sea sharks are targeted for their oil, which is rich in squalene, a molecule that’s used to make cosmetics and haemorrhoid cream.16

Elasmobranchs gain further efficiency from their skin. Rather than teleost scales, they’re covered in tiny, sculpted denticles – highly modified teeth – that reduce drag and help them slip through the water. This makes them not only more streamlined but also more silent, so they can sneak up on their prey.

The super-efficient lives of elasmobranchs can go on for a long time. Sawfish live for 40 years, dogfish for a century, and in 2016, Greenland Sharks were recognised as the longest-lived vertebrates. These fish live in deep Arctic waters where, at up to seven metres (23ft) long with mottled grey skin and only a very small dorsal fin, they look more like giant seals than sharks. And they’ve revealed their immense age in their eyes. Atmospheric tests of thermonuclear weapons in the 1960s sprayed a bomb pulse into the oceans, which has since trickled through marine ecosystems. This radioactive time stamp laid down in the lenses inside the Greenland Sharks’ eyes helped researchers work out that they can live for at least 270, and perhaps closer to 400 years, given a chance. And in these long, slow lives, many sharks take their time to get going. Great Whites only become sexually mature when they’re teenagers, and Greenland Sharks may mate for the first time when they’re 150 years old.

When they finally get around to making more of themselves, elasmobranchs usually meet up, form couples and mate, something that most other fish, such as teleosts, don’t do.17 Occasionally, divers find themselves in the right place at the right time to watch this happening, and catch glimpses of courtship rituals. Reef Manta Rays parade around, with a receptive female at the front being trailed by dozens of eager males. She will twist and turn and even leap from the sea, perhaps testing her potential mates to see which is the strongest. Eventually, she chooses a mate and lets him slide his mouth onto one of her pectoral fins; he bites down with his tiny teeth (which he doesn’t use for eating). Another male might come along and try to knock him off, but if he keeps a firm grip he’ll flip his body underneath and hold his belly close to hers.

Like all male elasmobranchs, mantas have a pair of modified pelvic fins, known as claspers, that dangle underneath. They look like stretched-out testicles but they act like a penis, transferring sperm into the female’s body. Like coelacanths, manta rays are ovoviviparous, with the fertilised eggs hatching inside the female and staying there. After a year of gestation, the fully-formed manta pups are born, either as singletons or occasionally twins, wrapped up in their wide fins like a baby in a blanket.18

Hammerhead sharks, Blue Sharks and various others are viviparous, meaning the females provide unborn young with food and oxygen from a placenta via an umbilical cord, in a similar way to mammals. They too give birth to a small number of fully-formed young. A third breeding option for elasmobranchs is to lay egg cases on the seabed (rather than ovoviviparity, this is known as oviparity – egg-laying). Also known as ‘mermaid’s purses’, the leathery egg cases look like giant ravioli pasta shapes, and they often wash up empty on beaches after the pups have climbed out. From the shape and size of the egg case you can work out which species it came from. Catshark egg cases have long curling tendrils at each end, which anchor them to strands of seaweed. Around the coasts of Australia, Port Jackson Sharks lay spiral-shaped egg cases, then pick them up in their mouths and wedge them between rocks. Ten months later, the pups hatch at around 20cm (7in), big enough to reach from top to bottom on this page.

For a handful of elasmobranchs there’s a fourth option: to go it alone. Female Bonnethead Sharks, Zebra Sharks, Swellsharks, bamboo sharks and sawfish are all known to have given birth with no male contribution. Their unfertilised eggs have, occasionally, developed directly into embryos, giving rise to genetically identical offspring, a useful tactic to switch to when mates are hard to come by. Insects often employ this trick, as do a few reptiles, birds and amphibians (as far as we know, mammals can’t to this without a lot of help from modern cloning techniques).

No matter how they’re born, an important aspect in the lives of elasmobranchs – which may seem rather obvious – is being big. Most stingrays are at least the size of a dustbin lid and they can be much bigger. In 2015, a Freshwater Whipray was captured in a river in Thailand that was more than 2.4m (7.9ft) in diameter and 4m (13ft) from nose to tail. It looked like an elephant that had been melted down, scooped up into a ball and then trodden on. The sting at the end of its tail was 38cm (15in) long, loaded with venom, and made from a hugely enlarged and modified denticle, the tooth-like structure normally seen in elasmobranch skin. Contrary to popular belief, stingrays only use their stings in defence, not attack.

As for the sharks, Dwarf Lantern Sharks are small enough that you could easily put one in your pocket, but most fully-grown sharks are much bigger. They include the three biggest fish alive today, the Whale, Basking and Megamouth Sharks (which range between roughly seven and twenty metres, or 22–65ft). Meanwhile, more than half of all newborn sharks arrive in the sea longer than the average human toddler.

Elasmobranchs aren’t alone on this branch of the fish evolutionary tree. Roaming the deep oceans are fish with rabbit-like heads, small mouths and nibbling teeth, and their bodies taper to a point, with a tail trailing behind like a ribbon. They’re sometimes known as rat tails, or rabbit fish, but are more commonly called chimaeras.19 Around 420 million years ago, during the Silurian period, this sister group broke away from the elasmobranchs. Many chimaeras have bizarre head adornments, including noses that look like someone grabbed them and gave them a good tweak. Male chimaeras generally have a retractable organ on their head, which they use during sex; it has an opposable tip which slots into a notch on the female’s head, stopping her from swimming off just when things start to get interesting.

Along America’s Pacific Northwest coast, divers venturing out at night might glimpse a chimaera commonly known as the Angel Fish. They have big viridescent eyes, shimmering bronze skin covered in white spots, and they swim through open water in slow, corkscrew turns with flicks of their triangular pectoral fins. A few years ago in Puget Sound off Washington State, researchers found a pure white, albino chimaera, a very rare un-pigmented find for any fish – a real angel.

As we approach the base of our fish evolutionary tree there are just two groups left, but it’s not a simple case of arranging them one after the other. This remains, in fact, one of the most controversial parts of the tree, with implications for the whole of vertebrate life.

These last fish groups look similar to eels (although all the way down here on the tree they’re only distant relatives to those slender teleosts). They have a round mouth at one end and a flattened, paddle-like tail at the other, and both have something of a nasty reputation. Lampreys start out life harmlessly enough. All 38 species are born in rivers as larvae that spend several years buried in mud, filtering the water for morsels of food floating by. Then they grow into metre-long (3ft) parasites. Migrating out to sea, most lampreys hitch onto the skin of their host, often teleosts of some kind, and stick themselves firmly in place. They then set about scraping a hole in the host’s skin with their sharp tongue before sucking blood or biting mouthfuls of flesh. The lamprey eventually unhitches itself and goes off to find its next victim; the host is depleted and may even die from its wounds.

Hagfish, the other group at the base of the fish evolutionary tree, have loose, scaleless pink skin that makes them look like they’ve crawled into a stocking. Compared to lampreys they’re hardly any more genteel, and have the unappealing habit of eating a carcass from the inside out. You’re likely to find one of the 70 or so species buried deep inside the decomposing body of a fish or a dead whale that’s fallen to the seabed. They make an entry where they can, either through an existing orifice or by ripping a hole, then settle in for a feast, leaving behind nothing but skin and bones.

Two odd habits set hagfish apart from other animals. First is their legendary ability to make extravagant amounts of gooey slime. Put a hagfish in a bucket and soon you will have a bucket full of transparent ooze, squeezed from a series of pores along its body. In 2017, a truck transporting 3.4 tonnes (7,500lb) of live hagfish overturned in Oregon, smothering the highway in stringy, white slime. It took emergency services hours to clear up, with high-pressure hoses and a bulldozer, while thousands of hagfish were still slithering around. The intended destination for them was Korea, where hagfish are eaten and their slime used as a cooking ingredient, as an alternative to egg white. Researchers are also busy studying hagfish slime with the idea of making new materials and fabrics from the stretchy, thread-like proteins.

The slime is thought to deter hagfish-hunting predators by clogging their gills. In fact, if they’re not careful, hagfish can quite easily suffocate themselves. To avoid this they tie themselves in knots – their second clever trick – and slide the knot along their bodies to rid themselves of their own goop. They’ll do the same thing if you grab hold of one, using a knot to push against your hand and release your grip.

Traditionally, lampreys and hagfish have been distinguished from the rest of the fish based on the features they don’t have. None of them have jaws. They’re the only surviving jawless fish (many other jawless fish are known, as we’ll see later, but they’re long extinct). They also don’t have complete backbones. But they do have a skull made of cartilage, and a stiffened nerve cord running along their back, the notochord. Consequently, they’re considered to be the two most ancient groups of fish. Which of them evolved first, lampreys or hagfish, may not seem especially important, but this question lies at the heart of a great evolutionary debate.

It had been widely thought that hagfish kick-started the entire vertebrate lineage, some time around 500 million years ago. Recent genetic studies, though, support an alternative view that hagfish aren’t the most ancient fish but are sisters to the lampreys. This view places the tight-knit duo together on their own branch of the vertebrate evolutionary tree.

This leaves us with a distinct gap between vertebrates and invertebrates, the animals with no backbones. The vertebrates’ closest spineless kin are tunicates, also known as sea squirts. As adults, they sit about in the sea, stuck to reefs and rocks, quietly filtering water. It’s in their younger stage, as larvae, that sea squirts reveal their vertebrate affinities, in the form of tadpole-like wrigglers, swimming around with a stiff notochord along their backs. This makes sea squirts firm members of the chordates – the major division of the animal kingdom within which the vertebrates sit – and they’re what we would find if we carried on our journey along the fish evolutionary tree to the next branch down.

The search is on for the animals that came between the sea squirts and vertebrates. What did those first vertebrates look like, the common ancestors of hagfish, lampreys and all the other fish? These are the real missing links in the vertebrate evolutionary tree, right here at the base. We can look up into the branches swaying above us, laden with so many thousands of species: fish with skeletons made of bone or bendy cartilage; fish that live in mountain streams and at the bottom of the deepest seas; fish with lungs and fish with legs. This tree is also occupied by every other vertebrate, from whales and dolphins that went back to the sea, to the people who do their best to be amphibious, scuba tanks fixed to their backs. For now, though, it’s still not clear how exactly this great lineage began.

How the flounder lost its smile

Isle of Man, traditional

A long time ago, in the sea near the enchanted Isle of Manannán, all the fish came together to decide who should be king. Each one hoped it might be them, so they all smartened themselves up and came looking their very best.

There was the Red Gurnard, Captain Jiarg, dressed in his fine crimson coat. Grey Horse the shark was there, big and fierce as always, with his skin polished to a shine. The Haddock known as Athag was there too, still trying to rub away the black spots that the devil had burnt on his skin.

Brae Gorm the mackerel swaggered about, certain that he would be king. He dressed himself in fine stripes of all the colours of the sea and sky, looking like a coat of diamonds. But the other fish didn’t like his bragging and his gaudy costume, and they turned their backs on him.

Instead of the mackerel, it was Skeddan the herring who became king of the sea. While all the fish celebrated, another arrived who had also hoped to be king, but he was much too late. It was the flounder, known as Fluke. ‘You’ve missed the tide,’ all the fish shouted. ‘Skeddan is now king!’ The flounder had taken too long getting ready, decorating himself in red spots. ‘Then what am I to be?’ he cried. Scarrag the skate replied, ‘Take that!’, and with his tail slapped the flounder, knocking his mouth into a crooked frown on one side of his face – and so it has been ever since.

Notes

1 Teleosts have been shunted between various different taxonomic ranks; nowadays they’re generally considered to lie somewhere between a sub-class and an order.

2 Throughout this book, I capitalise formal common names, mainly to distinguish them from descriptions. So, there’s a single species of Wahoo (Acanthocybium solandri) and many species of tuna.

3 Until recently, it was thought there were four sunfish species, the best known being the Ocean Sunfish (Mola mola). In 2017, a fifth species was tracked down after a four-year hunt by Marianne Nyegaard at Murdoch University in Australia. This one is Mola tecta (from the Latin for ‘hidden’), the Hoodwinker Sunfish.

4 This is why, should you want to slap someone with a dead fish, I would recommend you use a teleost.

5 This is according to the International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red List of Threatened Species. Most caviar-hunters don’t wait for the females to lay their eggs, but cut them out. There are a few initiatives to produce sustainable caviar.

6 Pronounced ‘bi-shears’.

7 Also known as actinopterygians, a broader grouping including all the fish we’ve met so far, higher up on the evolutionary tree.

8 Lungfish in fact have paired nostrils that connect through to the mouth and draw water over a layer of skin with receptors that bind to odour molecules in the water. Most teleost noses are blind-ended sacs, with two nostrils to draw water in and out again.

9 These machines are used in medical imaging to produce high-resolution slices through intact living tissue; these can be combined into 3D images.

10 The Bowfins’ ‘lungs’ are in fact thought to be a modified swim bladder.

11 Pronounced ‘sea-la-canths’.

12 There’s a risk that coelacanths could yet go extinct after all. The two species are listed by the International Union for the Conservation of Nature as Critically Endangered and Vulnerable to extinction, mainly from incidental capture in small-scale fisheries. There’s also been growing demand from idiots who think that eating coelacanths will make them live for longer.

13 The tetrapodomorphs are now all extinct; they included such beasts as the Eusthenopteron, Panderichthys, Ichthyostega and Acanthostega.

14 Unlike sharks, which almost all live in the sea, there are lots of freshwater stingrays.

15 Basking Sharks are now protected under EU law.

16 Squalene is also sold by health companies in capsule form, despite scanty evidence of any known health benefits.

17 With a few exceptions, the usual way of things for fish is for a female to lay eggs in the water and a male to add a squirt of sperm to externally fertilise them.

18 The name ‘manta’ comes from the Spanish word for blanket.

19 They are the sole surviving order of the Holocephali, a sub-class with dozens of fossil species. Together with the elasmobranchs, they form a class called the Chondrichthyes.