Stripes of inky blue and ripe banana-yellow run across the fish in front of me; its eyes are hidden beneath a black mask, like a gem thief. Emperor Angelfish somehow manage to be flamboyant and demure at the same time, which I expect is one reason why I like them so much. It’s big for an angelfish, roughly as long as my fingertip to my elbow, and it slides under a dark ledge before spinning around to watch me from safety.

It’s a species I always hope to see, and whenever I do I feel a contented sense of them always being out there, somewhere in the world, even when I’m not looking. I’ve seen Emperor Angelfish in the Red Sea, in the Maldives, the Philippines, Australia and Fiji; the same faces in different places.

This is Rarotonga, a mountainous, forest-clad island in the South Pacific encircled by a coral reef and a clear, turquoise lagoon. At high tide, I wade out from the beach – no boat required – and plan to stay as long as the tide will let me, threading my way around coral boulders, watching fish.

The lagoon is brimming with colourful life, like a well-stocked aquarium but without glass walls. I paddle around, taking in as much as I can. At first sight coral reefs can be an overwhelming scramble of colours and shapes, so dazzling and busy it’s hard to make any sense of it all. But there are tricks for spotting fish and for working out what’s what.

Start by looking at the shapes of fish. Common families have distinct profiles that can help you distinguish a bullet-shaped wrasse from an oval damselfish, a stout, wide-tailed grouper from a slender, fork-tailed fusilier. You can learn to pick out key characters like a soldierfish’s big eyes, a goatfish’s whiskery barbels hanging from its chin and the forehead of a unicornfish. With a search pattern in mind, you’ll begin to notice groups of fish with similar shapes. They also behave and move in certain ways. Damselfish are the little ones, hanging about in flickering shoals over colonies of coral, darting between the coral’s branches and fingers when you come near. Blennies usually hide away in holes in coral boulders, and occasionally pop their heads out. Gobies look similar to blennies, but they can be bigger and often live in burrows on the seabed, together with a shrimp partner; the shrimp industriously shovels gravel out of the burrow while the goby watches out for trouble. Wrasse and parrotfish row themselves through the water with beats of their pectoral fins; triggerfish swim by undulating their large dorsal and anal fins, on their back and belly; cardinalfish hang motionless close to the reef.

Colours and patterns can then narrow things down and help you to identify particular species. Some of the easiest to pick out are butterflyfish and angelfish, which have bold colours, spots and stripes. Panda Butterflyfish are unmistakable, with their dark eye-patches, as are Raccoon Butterflyfish, with white and black bandit eye-masks like their furry namesakes. Keyhole Angelfish are deep blue all over except for an oval white patch, which you might imagine you could put your eye to and peer through.

As you get to know fish and start spotting your first few species, you’ll learn to make mental notes of things you don’t recognise to look up later. I do this in Rarotonga’s lagoon. There’s a white and yellow butterflyfish with a dark blot that’s smudged as if it got caught in the rain, and an angelfish, yellow all over, with neon blue edges to its fins and a ring around each eye like a pair of spectacles. Later, I flip through my identification guide and learn these two are Teardrop Butterflyfish and Lemonpeel Angelfish.

Sometimes there are rare locals to look out for. In Rarotonga, just in case, I keep an eye out for an angelfish with a scarlet body and five minty white stripes running across it. This is the Peppermint Angelfish, discovered here in 1992 on a deep reef and never seen anywhere else in the world. A living specimen was collected during a research expedition run by the Smithsonian Institution in Washington DC and donated to the Waikiki Aquarium in Hawaii, so researchers could study it and members of the public see it. The aquarium keepers turned down numerous offers from trophy-hunting private fish collectors of up to $30,000 for this singular little fish. But I’m kidding myself, really, that I’ll see one. Peppermint Angels have only ever been seen much deeper, far beyond the reach of my lungful of air.

The tide begins to fall and I dawdle reluctantly back towards the beach as the water drains from the lagoon. Bright fish still dart about, right in front of my mask. Many are adolescents that will change colour as they grow up. Among them I spy a rare treasure that makes me smile, sending a dribble of water into my mask and up my nose. It’s the shape and size of a large blueberry, only canary yellow with black polka dots and a pouting snout, and it’s bobbing restlessly left and right. It could be a tiny helium balloon being dragged behind a restless child, but it is in fact a young Yellow Boxfish. When it gets older, it will lose its bulbous profile, become more box-shaped and swap its bright yellow outfit first for dirty mustard, then for blue.

Picasso Triggerfish also patrol the lagoon, the size and shape of a flattened rugby ball. Airbrushed patterns adorn their flanks with subtle shades of yellows and tawny browns. It looks as if an artist then dragged his fingers through the wet paint, leaving four white stripes. Between the fish’s golden eyes run bands of ultramarine; dripping down its face are iridescent blue tear streaks, and on the upper lips a pencil moustache to match. Picasso Triggerfish hatch in this audacious birthday suit, which they’ll keep throughout their lives. Finally I stand up and walk to the beach and I see minute painted Picassos, their patterns shrunk down to a tiny size but still unmistakable, as they zip around in a finger’s depth of water.

Colourful fish don’t only live on coral reefs. When adult Coho Salmon leave cold North Pacific waters to spawn in forest-lined rivers, they transform from silver to crimson. On Britain’s south coast I’ve seen turquoise spots gleaming in a tide pool, like a pair of eyes gazing up at me, from the back of little fish called Cornish Suckers. In North America, along the coast between San Francisco and Baja California, bad-tempered fish called Sarcastic Fringeheads live inside big, empty seashells. Males charge at each other and engage in irate head-to-head contests, opening their enormous jaws like umbrellas that are yellow and red on the inside. Further east, streams and cool, clear creeks across the Mississippi Basin are home to almost 200 species of darter. Some of these finger-sized fish live only in a single stream and most are distinguished by their bright patterns. Candy Darters are iridescent jade striped with orange; Banded Darters come dressed in bright emerald stripes. A 2012 study revealed that the Speckled Darter is in fact at least five separate species with distinct colours. The newly recognised darters were named after US presidents did their bit for who environmental protection; among them, the Spangled Darter Etheostoma obama is vivid orange, with blue spots and stripes.1

Why fish are so colourful is a question many ichthyologists have pondered. And through their studies they’ve seen that fish expertly use colour as a tool – to hide and shock, warn and woo. Fish adapt to the way light and colours behave underwater, as sunlight splits apart and wavelengths shift and change. Studies of colourful fish are also revealing broader details of how the living world works. Fish colours are showing the startling pace of evolution and they offer up clues as to how the polychromatic world around us came to be.

In December 1857, naturalist and collector Alfred Russel Wallace arrived on the Indonesian island of Ambon, where he hired a boat to cross the bay and reach the island’s interior. He was part-way through an eight-year, 22,000km (14,000-mile) journey around Southeast Asia, during which he gathered tens of thousands of animal specimens, made detailed observations of people and wildlife and, independently of Charles Darwin, formulated a theory of evolution. The water in Ambon’s bay was so clear that Wallace could see all the way down to the seabed from the surface. Without even sticking his head beneath the waterline, he saw for the first time a coral reef. It was, he later wrote in his book The Malay Archipelago, ‘one of the most astonishing and beautiful sights I have ever beheld.’

The hills, valleys and chasms of what Wallace called ‘these animal forests’ made of coral and sponges were inhabited by shoals of fish, ‘blue and red and yellow … spotted and banded and striped in a most striking manner … It was a sight to gaze at for hours.’

Twenty years later Wallace wrote an essay exploring ideas of why many living things are brightly coloured. For species to daub themselves in such showy pigments would seem at first to be a dreadful idea. Eye-catching displays are surely an open invitation to passing predators to come and dine. Equally, the hunters should conceal themselves as they sneak up or swoop down on their prey. Nevertheless, dramatic colours have evolved time and again throughout the natural world, and especially among fish. In Wallace’s view, this mostly comes down to animals trying to keep themselves safe.

‘Even gay colours are very often protective,’ Wallace wrote, ‘because the earth and the sky, the leaves and the flowers, themselves glow with pure and vivid hues.’ Living in such a colourful world, it follows that animals might use bright colours to hide themselves. There are green caterpillars with pink spots that resemble the flowering heather they like to nibble. Wallace pointed out that the green feathers of many tropical birds, from parrots to white-eyes, bulbuls, barbets and bee-eaters, match the evergreen foliage they inhabit. And in polar regions white is the colour of choice, for Polar Bears and Arctic Foxes, all the better for hiding in snow and ice.

Reef fish use their colours as camouflage, Wallace proposed, to hide among bright seaweeds, anemones and corals. The examples he gave included the seahorses and their Australian relatives, with ‘curious leafy appendages’, the Leafy and Weedy Sea Dragons. Since Wallace’s time, divers and scientists have discovered many other well-camouflaged seahorses, with pink and orange pimples that match the knobbly sea fans where they perch, or yellow and purple tufts like their soft coral homes.

The Warty Frogfish is another reef species with immaculate camouflage. This dumpy fish sits, mostly unmoving, and alters its colour and texture to match its surroundings, often yellow and orange sponges. It’s the kind of fish that’s so well hidden you need two fingers pointing from different directions to show another diver where it is. In 2016, a pure white frogfish was spotted in the Maldives. This was shortly after the reefs were hit by a major coral-bleaching event, triggered by high water temperatures. Heat-stressed corals expel the tiny, pigmented algae that live in their transparent tissues, so they lose their colour and become ghostly white. The frogfish had quickly responded to this change in its world; it had even sprouted small green tufts, apparently to match the seaweeds that were beginning to grow over the dead white coral.

For slow-moving fish like seahorses and frogfish this form of colourful camouflage can work astonishingly well. But what about more active fish? The scene behind them is constantly changing and calls for more sophisticated camouflage. A 2015 study revealed how Slender Filefish from Caribbean reefs perform lightning-fast costume changes. Second by second, a filefish choses from at least 16 different outfits to coordinate with whatever it happens to be swimming past: a patch of green seaweed, a pale, lacy sea fan or a golden frond of soft coral. These little fish are always dressed for the occasion.

Some fish even dress up like their prey. In the waters around Lizard Island on the Great Barrier Reef live small, predatory fish called Dusky Dottybacks, a single species that can be either yellow or brown. They hunt for young damselfish, of either a yellow or a brown species. A research team, lead by Fabio Cortesi from the University of Basel in Switzerland, conducted a neat experiment to test how these predators use their colours. Divers stocked an experimental area of wild reef with either yellow or brown damsels, then in various combinations they added the predatory dottybacks, again either the yellow or brown colour morphs.2 After two weeks, the divers checked on the fish and saw that the predators had changed colour to match their prey. Further studies in the lab showed that the predators had more success when they were the same colour as the fish they were hunting. By matching the damsels’ colour, the predatory dottybacks can sneak in and get closer to the young fish, who are less wary and presumably mistake the dottybacks for adults of their own species. It seems the dottybacks are performing a fishy version of a wolf in sheep’s clothing.

Colours and patterns also help fish hide in plain sight, by breaking up their outline. The blue and yellow stripes of Emperor Angelfish, rather like a zebra’s stripes, could make it difficult for predators to pick out the shape and target of a fish. In shoals of stripy fish it’s tricky to see where one fish begins and another ends. Fish also use their patterns to hide particular parts of themselves. The Emperor’s dark eye-masks could reduce the chances of predators pecking at their eyes.

Butterflyfish often combine eye-stripes with large, dark spots elsewhere on their bodies, often ringed in iridescent blue. It’s thought these could be false eyes, diverting attacks away from a fish’s delicate head-end. Eye-spots may also confuse predators when their prey swims off in apparently the wrong direction.

Despite decades of research, however, these theories are proving tough to test and there’s still no consistent view for why so many different animals have evolved eye-spots, from fish to birds, butterflies and moths. In another study of damselfish living around Lizard Island, researchers didn’t find any juveniles with bite marks near the spots on their tails, suggesting the markings aren’t confusing predators into attacking the wrong end. Monica Gagliano from James Cook University in Queensland, Australia, proposed that the spots could be ‘decorative leftovers’ from some past survival advantage that no longer applies. Or maybe predators more recently got smart to eye-spots and are no longer fooled.

In his essay on protective colours, Alfred Wallace noted that nocturnal animals tend to be dusky and dark to blend in with the shadows of the night. By contrast, the common colour for underwater night-dwellers isn’t black but red. There are red squirrelfish, soldierfish and bigeyes, all of them tropical, nocturnal species. Red is also a common costume for animals living in the deep. A newly discovered species of the seahorses’ relative, the sea dragon, was recently filmed for the first time deep underwater off the coast of Western Australia. It has skin the colour of rubies. On deep underwater mountains live Orange Roughies; alive they’re brick red, fading to orange when they die. All these fish evolved their ruddy complexions because of the way sunlight behaves in water.

When light from the sun reaches the Earth, it’s composed of a blend of colours, each with a certain wavelength. Humans can generally perceive colours ranging from short-wave blues and purples to longer-wave oranges and reds. All wavelengths of light pass with equal ease, more or less, through air, and when we see them all together our brains interpret them as white. Passing through water, however, sunlight begins to separate out, as longer wavelengths, with less energy, are quickly absorbed by water molecules. It means that in clear water below 20 metres (65ft), very little red light remains. Go deeper and other colours blink out; oranges are lost, then yellows and greens. Blue light, with its energetic, short wavelength, penetrates the deepest. This is why most of the oceans are blue. It follows that lots of creatures inhabiting the open sea evolved to be blue, to match their surroundings.

Why, then, are deep and nocturnal animals red when that isn’t the colour of the sea itself? The reason lies in the way coloured pigments work. Most objects appear a certain colour because they contain pigment molecules that absorb specific wavelengths of light and reflect others – and it’s the reflected colours that we see. Hence a leaf in autumn looks red because it contains anthocyanin pigments that absorb green and blue light, and reflect red. However, if you were to take that red leaf on a deep dive it would quickly fade to inconspicuous grey then black because there’d be no more red light available to reflect. The red pigment would be unable to show its true colour. Similarly, as the sun sets, the first wavelength to ebb away underwater is red, making this a useful colour for both nocturnal and deep-water camouflage.

In shallower waters, during the day, red can be a good colour not for hiding but for being as obvious as possible. Alfred Wallace wrote about the colours and patterns that serve as a warning to other animals. Bright colours can call attention to hidden poisons or dangerous spikes and stings that attackers do well to learn to recognise and avoid, like the black and yellow stripes of bees and wasps. Wallace didn’t refer to such cautionary colours in fish, but there are plenty. Lionfish have red and white stripes, warning of their long, venom-tipped spines. Surgeonfish are named after the venomous blades at the base of their tails, which are often bright warning colours.

Some colourful fish paint themselves in warning colours when in fact they’re quite harmless. Innocuous species gain protection by wearing false warning colours and pretending to be poisonous. One such mimic is the Whiteblotch Sole which, in its young stage, masquerades as a toxic flatworm. The fish and the flatworm look remarkably alike. Both lie flat on the seabed and ripple slowly along, their black bodies fringed in orange, with large white spots. Mistaking it for a bad-tasting flatworm, predators should leave the sole well alone.

Wallace concludes his musings on animal coloration discussing what he calls ‘one of the most curious chapters in natural history.’ He considers how colours are passed on and perfected from generation to generation. Pigments and patterns vary within a population of animals and some will give individuals a ‘better chance of life’, as he puts it, by making them less conspicuous or by warning off enemies. Those most useful colours will pass from parents to offspring; the same selective process continues in each generation until camouflage or warning colours become so good that enemies give up and focus attention on other species. But it doesn’t stop there. Over time, predators may change too, and get better at seeing through the deception, so generations of prey will continue to adopt the best, most protective colours and patterns. Wallace didn’t label it as such, but this is evolution in action. It leaves us, he writes, with a satisfactory clue as to why we see such ‘varied coloration and singular markings throughout the animal kingdom, which at first sight seem to have no purpose but variety and beauty.’

Wallace’s ideas explain the bright colours of many animals, but not all use colours to be secretive or scary. There are fish that aren’t hiding or poisonous, or even pretending to be poisonous. Since he wrote his essay on protective colours other theories have emerged, including the possibility that fish are writing colourful messages on their bodies intended for other fish to read.

Fifty years ago, Austrian zoologist Konrad Lorenz came up with the idea that many coral-reef fish decorate themselves with what he called plakatfarben, or poster colours. He proposed that they use their bodies as a living billboard, adorned in brash adverts declaring their identity and gender.

Lorenz, a pioneer in studies of animal behaviour, was especially interested in aggression. He kept coral-reef fish in aquaria and watched how they got along – often not at all well. Fights frequently broke out between members of the same or similar species. They would nip, bite and eventually kill each other. To see what happened in a more natural setting, Lorenz went to the Florida Keys and Kaneohe Bay in Hawaii. Snorkelling with wild fish, he saw similar conflicts playing out, although usually not fatally; rather than hang around and get a beating, the losing fish would quickly swim away. Their bright colours and patterns, he thought, were telling fish who was who. This is similar to the team colours sports fans wear, except that fish aren’t looking for a fight with rivals but with members of their own team. Other fish of the same species can be their greatest competitors. Lorenz became convinced that fish use their bright displays to stake out territories and fend off intruders, nailing their colours to the reef.

Lorenz’s poster-colour theory has been supported but also refuted by various subsequent studies. Some fish seem to fit the model that brighter colours belong to more argumentative, aggressive species. Red-toothed Triggerfish, for example, are coloured a relatively inconspicuous deep blue all over, and they are quite a gentle species; meanwhile, Picasso Triggerfish, like the ones I saw in Rarotonga, are far more ostentatious in their colours, and more quarrelsome. There are, however, other species in which the opposite is the case: angry fish with drab colours.

A further strand of evidence in favour of poster colours comes from the fact that in many species, adults and juveniles look completely different. In their early years Emperor Angelfish are dark navy, with white and electric blue concentric rings across their bodies. Only when they’re around two years old will their yellow and blue stripes gradually seep through their skin, replacing the rings. It’s thought this costume change allows younger fish to appease the adults.

In a 1980 study of Emperor Angelfish in the Red Sea, German biologist Hans Fricke went diving and took down with him two small painted wooden fish, one with adult stripes, the other with juvenile rings. He fixed them to the reef in the territories of various emperors and watched their response. You might think the real fish wouldn’t be fooled by a non-moving, wooden replica but they did seem to react differently to the two patterns. Adult emperors were more likely to attack the model adult fish and generally left the young one alone. This simple study suggests that the young fish’s colours may placate truculent adults and win them safe passage across the reef, until such time as they’re ready to make a bid for their own territory and reveal their mature colours. Several other angelfish species wear a school uniform similar to the emperors’, and the species can be difficult to tell apart when they’re young. Again, this lends support to the idea that young fish are trying to avoid getting into fights.

This doesn’t seem to apply to all fish, though. In another study, this time of large damselfish called Garibaldi that live in Californian kelp forests, the juvenile colours seem to offer little protection. Thomas Neal from the University of California (Santa Barbara) gathered various young Garibaldi, some still peppered with the metallic blue spots of their youth and some that had recently lost them and were orange all over. He presented these similar-sized but differently coloured juveniles to adults and watched as they launched aggressive attacks on the fish with spots.

Rather than chasing off intruders, some poster colours invite them to stay. Various species of wrasse and gobies take on the role of dentists and hygienists on coral reefs. They set up cleaning stations and spend their days pecking away dead skin and scales from client fish, cleaning between their teeth and pulling blood-sucking parasites from their skin. Many of these cleaner fish have blue and yellow stripes, a common colour combination on the reef. These two colours can be seen from the furthest away in clear, blue waters. And being widely separated on the colour spectrum, blue and yellow contrast strongly underwater. Wearing these colours, cleaner fish advertise their services far and wide.

Theories that fish use colours to hide themselves away or to shout as loudly as possible rest on the assumption that they themselves can see these colours. And indeed they can. Fish have eyes with a similar basic structure to our own. Like us, they have a pair of liquid-filled orbs with a narrow pupil to let in light and a lens to focus an image on the retina, a layer of light-sensitive cells at the back. One difference between fish and human eyes, though, is the lens shape. As light passes from air into our eyes, it already begins to bend inwards and focus towards the retina, because the refractive index differs between air and liquid. Muscles then adjust the shape of our elliptical lens to fine-tune the image (except for those of us who are long or short sighted and need glasses to help). Open your eyes underwater and everything becomes blurred because you’ve instantly lost that focusing power between air and eyeball, and light passes straight in. If fish had lenses shaped like ours, they’d have to wear incredibly thick spectacles to see clearly. Instead, they have spherical lenses inside their eyes, which bend light much more strongly. Next time you cook a whole fish for dinner, dig into its eye and you’ll find the lens, neat and round like a ball bearing, and opaque once you’ve cooked it, because the proteins inside have been denatured like those in a boiled egg. When focusing on things near or far away, fish move their whole lens around inside their eyeballs, like moving a magnifying glass closer or further from your eye.

Colour vision comes courtesy of specialised light-sensitive cells in the retina known as cones. Each cone responds to a specific range of wavelengths; they absorb photons of light and fire nerve signals to the brain. By comparing signals from different cones, the brain interprets colours. Humans generally have three cone types, and our brain translates their firing as a continuous rainbow of colours between indigo and red.

To determine the colours fish can see, biologists dissect out their retinas and use machines called spectrophotometers to beam light on them and measure which wavelengths they absorb. Since the 1980s there have been micro-spectrophotometers, which shine thin needles of light onto individual cone cells. Studies like these have shown that, between them, fish have a whole range of cones. Some species have two, others have four, and some are sensitive to wavelengths that humans can’t see.

For example, various freshwater fish have evolved red-shifted vision. They can see far-red and infrared light, which we can’t. The reason for this is that as sunlight filters through freshwaters, flecks of mud and algae absorb certain wavelengths and push ambient light towards the red end of the spectrum, so there’s more red light to see by. Not only that, but some migratory species change the colours they see best as they move inland from the sea. Salmon and lampreys see blue light better while they’re swimming out in the blue oceans. Then, when they move inland, they adjust their visual pigments to see far-red and near infrared light. Lemon Sharks change their vision in the other direction. As youngsters they inhabit murky waters, among the roots of mangrove forests, and later in life move offshore, adjusting their vision from red to blue as they go.

There are fish that can see ultraviolet light. It had long been assumed that fish wouldn’t be able to see UV since it gets scattered and noisy underwater, making it of little use. But it turns out that for short-lived species, UV is the perfect wavelength to send out secret, close-range messages that other fish, mostly predators, are blind to. Studies of damselfish reveal they recognise each other and distinguish species from intricate patterns on their faces that reflect UV light. Two species of little yellow damselfish, Ambon and Lemon Damsels,3 are almost identical to the human eye except their UV facial patterns differ. These patterns seem to act as hidden poster colours that damsels can see but predatory fish generally can’t. Predators tend to be longer-lived and have UV filters in their eyeballs – their own inbuilt sunglasses – probably to protect them from years of sun exposure. The smaller, short-lived species seem to take advantage of this, and use UV decorations to communicate with each other without being spotted by their enemies.

Fish produce their dazzling, vibrant colours with specialised cells in their skin called chromatophores. Pigment granules give these star-shaped cells particular colours. Common types include black melanophores, red erythrophores and yellow xanthophores. Extremely rare are cyanophores, the cells with blue pigments. So far they’ve only been detected in two animals, both of them fish: the Picturesque Dragonet and its close relative, the Mandarinfish.4 I’ve spotted a Mandarinfish, the size of my little finger, peeping from a branching coral in a shallow lagoon in Palau, in the western Pacific. It briefly showed me its splendid green and orange body patterns, and wide fins trimmed with intense ultramarine, like powdered lapis lazuli.

Apart from these two blue fish, all the other blues in the living world are not pigments but structural colours. Instead of simply reflecting particular wavelengths, as pigments do, structural colours are produced when light bounces around inside a material and gets reflected, diffracted and scattered in different ways. There are structural colours throughout nature, from blue skies, rainbows and blue eyes to a butterfly’s wings and a Vervet Monkey’s brilliant blue scrotum. The common silvers and blues in many fish are structural colours made by another type of skin cell called iridophores. These contain guanine crystals and act like tiny mirrors, reflecting and interfering with the light that falls on them. They gleam in a similar way to the nacre (or mother-of-pearl) made by molluscs, and indeed fake pearls have often been made by covering glass beads with ground-up fish scales.

Layers of chromatophores and iridophores combine to produce all the fish’s colours and decorations. These can change, gradually or within split seconds as muscles alter the orientation of crystals and squeeze the chromatophores tight or stretch them out, hiding or revealing the pigments inside.

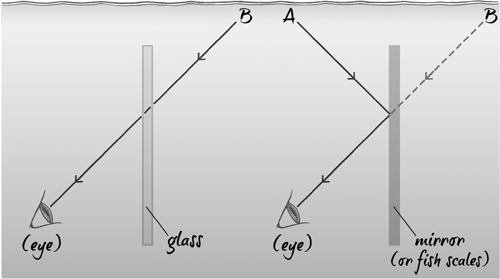

In open waters many silvery fish use layers of iridophores to disappear from sight, even though there’s nothing to hide behind. Anchovies, herring, mackerel and tuna take advantage of the unique light conditions underwater to camouflage themselves. To grasp how this works, first imagine a sheet of clear glass hanging vertically in open water. If you look up at the glass from slightly below, it’s invisible because light passes straight through and all you see is the water behind it. By contrast, out of water, you can usually see a sheet of glass because some light reflects off it and back at you, which doesn’t necessarily match the background; you might see yourself in the glass. Now, back underwater, replace the glass pane with a mirror. Unless a shoal of fish swims right past and you see their reflections, the mirror disappears just like the glass did. All you see is blue light that exactly matches the background. This happens because as daylight seeps down through water, it fades in a uniform way and is the same intensity around a horizontal plane; if you spin slowly around underwater, the brightness of water you’re looking at won’t noticeably change. The key thing is that the submerged mirror reflects the light in front of it, and this is of the same intensity as light behind it, on the other side of the mirror (in the diagram, light beam A matches light beam B). It’s impossible to know if you’re looking at a reflection in a mirror or peering through a pane of glass at the patch of water behind it – the two appear just the same. In this way, fish can also vanish underwater by covering their bodies in mirrors, so they blend in with the water around them. For this to work they have to keep their silvery bodies vertical. This is probably one reason why many species are incredibly thin and compressed from side to side. Fatter fish get around this by arranging stacks of crystals vertically within their skin, even on the rounded parts of their bodies, creating the same effect as a flat mirror. But still fish move and deviate from vertical, breaking their disappearing act, which is why silvery schooling fish glint and flash as they swim around in spirals.

How a mirror, or a silver-sided fish, behaves like a pane of glass and disappears from view underwater.

The best way to appreciate the bright pigments and gleaming shine of fish is to watch them from beneath the waterline while they swim around in front of you. As soon as they leave the water, fish’s colours and lustre quickly fade; no surprise, really, given that they evolved to be viewed underwater. Before underwater photography, the only way to capture and hold onto their brilliance was via the skilled work of artists, who ideally had seen the living fish themselves, sometimes in remarkable circumstances.

In March 1790, the British Naval ship HMS Sirius struck a coral reef next to Norfolk Island, almost 1,450km (900 miles) off the east coast of Australia. It was the flagship of the First Fleet, the ships that had come to set up a penal colony in Australia a few years earlier. When the ship foundered, the first thing Captain John Hunter did was to make sure nobody drowned. All 200 people, mostly British convicts, were taken safely ashore. Over the next few days as many provisions as possible were rescued from the hold, before the ship broke apart. Among the belongings that came to shore was a paintbox belonging to midshipman George Raper.

Since he left Britain aboard the Sirius three years previously, Raper had been painting charts and ports along the route to the southern hemisphere. Shipwrecked and facing dwindling supplies and starvation, Raper nevertheless turned his attention to painting the local wildlife.

When rescue eventually came 11 months later, Raper brought with him a collection of intricate, colour paintings including many fish from the waters around Norfolk Island. There’s a Sweetlip Emperor, with scarlet fins and yellow lips, and a Sandager’s Wrasse, with purple and green blush on its cheeks; both are easily recognisable as species that still live around the island today.

Other fish artists weren’t quite so true to life.

Earlier in the 18th century, on the island of Ambon in Indonesia where Alfred Wallace would later marvel at the coral reef, a Dutchman spent several years drawing and painting fish. Samuel Fallours served as a soldier and then a clergyman’s assistant in the Dutch East India Company. Local fishermen brought him fish that became the subject of paintings which Fallours sold to Company officials and European collectors. His elaborate artwork was reproduced in several books, including Poissons, écrevisses et crabes (Fish, crayfish and crabs), published in the Netherlands in 1719. It was the first colour book of fish and only a hundred copies were ever printed, making it one of the world’s rarest natural history books.5 The pages are filled with a stunning menagerie of strange creatures. Fallours’s drawings are highly stylised, more artwork than meticulous illustration, but still it’s possible to work out many of the species he drew. There are boxfish and triggerfish, lionfish and butterflyfish. Certainly he was more creative with his paintbox than George Raper, perhaps deliberately, to sell more pictures to his European clients who avidly collected exotic novelties. Stripes and spots are bold and exaggerated; bodies are filled in with invented geometrical patterns and ornamental twirls. If there had been an aquarium tank in Wonderland, these are the animals Alice would have watched through the glass.

On real fish species, extraordinary acts of colour often come about because females prefer the brightest mates. Males strike flamboyant displays. Choose me, choose me, they quietly shout. I am quite the best father you’ll find. You can see the signature of sex written across many animals’ bodies, usually in the differences between males and females. In general, females are sombre and inconspicuous, while males are far more splendid and eye-catching. The peacock’s plumage and the Mandrill’s blue and pink rump are prime examples. These and many other gaudy male characteristics become exaggerated over time by the mingling of two types of genes: one produces colourful attributes, the other leads to females who find those colours attractive. When a female chooses to mate with a colourful male, she’ll probably produce either male offspring that are vivid like their dad or females that share her penchant for those same bright colours. The girls don’t need to show off as much as their brothers and they’ll carry the colourful genes, but keep them hidden. Those genes for colour and colour preference are passed on together down the generations and over time produce ever brighter males, along with females who find them fetching.

Various fish originally by Samuel Fallours, possibly wrasse, pufferfish and lionfish, from Poissons, écrevisses et crabes, 1719.

All of this raises the question of why females prefer colourful mates in the first place. Far from being a whimsical choice, bright colours can in fact be a clear sign of a male in good condition and a worthy partner with top-notch genes. In fish, oranges and reds are especially good signs. These colours are carotenoid pigments that fish can’t make themselves and so come exclusively from their food, mostly from shrimp, crabs and other colourful invertebrates (it’s the same reason flamingoes are pink). To put on a colourful display, males have to eat a lot of food. It follows that the brightest males are well-fed, healthy, strong swimmers with good foraging skills, all qualities that tend to be underpinned by good genes. By choosing colourful mates, females are securing a good genetic inheritance for their offspring.

Striking male colours are associated with female choice in many fish, from multi-coloured American darters and blushing red salmon to sticklebacks with red bellies, Zebrafish that court each other with brief bright flashes, and parrotfish that begin life as subtle females, then change sex and change colour to become flamboyant males. And there’s one particular fish species that’s shown how the watchful gaze of females can be an extremely potent force, and how sex can drive evolution in certain colourful directions. These fish have been given a few different common names over the years. They’ve been known as ‘millions’ because there are so many of them, and ‘rainbowfish’ because the males are covered in colourful spots, stripes and splashes. Most commonly, though, these little, 3cm- (1in-) long fish are known as Guppies.

They were named after an Englishman, Robert Guppy.6 He came across the species 150 years ago, although he wasn’t in fact the first person to find them. A few years earlier they’d been spotted by German explorer Wilhelm Peters. But it was Mr Guppy who brought these little fish to the attention of the English-speaking world, which is why we now have Guppies and not Peters.7

Since their discovery, Guppies have become some of the most widespread and cosmopolitan fish; they’ve been introduced to freshwaters worldwide as part of attempts to control mosquito larvae and stem the spread of malaria; they’ve spent time on the International Space Station; and they live in their multitudes in aquarium tanks as much-loved pets.

Originally, before people started moving them around and off the planet, Guppies were native across the Caribbean and into South America. Mr Guppy found them in Trinidad. Across the island’s northern coast runs a mountain chain covered in lush cloud forests that are home to Howler Monkeys, Ocelots, Musk Hogs and critically endangered Golden Tree Frogs. Rivers and waterfalls tumble down from these cool, misty elevations, filling up clear pools and streams that are home to Guppies.

Throughout the last 60 years, a succession of biologists has scrambled through Trinidad’s montane forests to study Guppies in their wild habitat. Early on, wife and husband team Edna and Caryl Haskins from the US were the first to notice that not all Trinidad’s Guppies are equally colourful. In some ponds and streams they found males fluttering like rainbows, in others they looked more like females, with muted colours.

In the late 1970s, John Endler from Princeton University in New Jersey came to Trinidad and began photographing Guppies. His pictures revealed an intriguing sequence. Near the top of the mountains, when he dipped in pools, scooped out fish and took their photos, he saw the most colourful Guppies. As he worked his way downwards from pool to pool, the fish’s colours gradually faded away.

Endler also noticed that other Trinidadian fish varied from place to place. In the higher ponds he found just a single predatory species, the Leaping Guabine. This gets its name from its habit of occasionally leaping from the water to snatch beetles and ants from overhanging vegetation. On rare occasions, Leaping Guabines will eat a few small Guppies. Lower down the mountains, and in certain deep valleys, Endler found a greater variety of predatory fish, including a voracious hunter called the Millet – the Guppies’ most formidable enemy. Millets don’t venture upstream because waterfalls and rapids form barriers, which means the headwater streams and pools remain a much safer place for Guppies, out of the range of these hungry foes.

As Endler contemplated the varying fish communities from the top to the bottom of Trinidad’s mountains, a question arose in his mind. Are male Guppies treading a fine line between being seen and being eaten? On the one hand they need to be colourful enough to attract females; on the other, they can’t be so colourful that predators easily spot them.

Using thousands of photographs and fish measurements, Endler revealed a beautiful correlation. Male Guppies are at their brightest in the safest ponds with the fewest predators; there they have lots of big spots, especially in blues and shiny conspicuous hues. Where more predators prowl, the males’ colours are at their most neutral.

But, as every science student should know, correlation does not necessarily imply causation. It could be merely a coincidence that the Guppies’ vulnerability and drab colours seem to be linked. To test his idea further, Endler performed some experiments.

In July 1976, he picked a dangerous (for Guppies) stream lower down in Trinidad’s mountains, where Guppies lived alongside lots of Millets. He scooped out 200 Guppies, snapped pictures of them all, then released them in another stream not far away, one that was cut off by a waterfall. In their new home the Guppies cohabited only with Leaping Guabines, the moderate predators that pay them little attention. Essentially, Endler had switched off the predation pressure.

Two years later, Endler went back and scooped out Guppies from this translocated population and took their pictures. In the relatively short time they’d spent away from their main enemies, the Guppies’ colours had intensified. It wasn’t that the individual fish had changed colour, but that the brightest males had been the most successful in attracting females and had fathered lots of offspring, passing on their colours. Within just a few generations8 the genes for bright male colours had spread and the average colour of new male Guppies became more vivid. Compared to the parent population they came from (which Endler also checked on), the liberated males had bigger, more colourful spots.

By manipulating the Guppies’ predicaments, Endler uncovered vital clues as to how evolution works when multiple factors are at work – and unusually, he had done this in the wild and not in a laboratory. Females select for bright colours, and predators keep flamboyance in check; these two conflicting forces act on a population, shifting and changing over time. When predation is higher, males are most successful if they tone down their mating colours. And when conditions are safer, it pays for males to be as bright as possible, to impress females.

Not content with just his wild studies, Endler also took some Guppies back with him to Princeton. There he built a series of ponds to mimic Trinidad’s streams. He made some of them relatively safe, stocking them with Leaping Guabines, while others were more dangerous, and stocked with Millets. Then to each pond he introduced a mix of Guppies.

After just 14 months he saw the male Guppies in safe ponds had the brightest colours. In dangerous ponds, the males’ spots had shrunk and the blue and iridescent spots had disappeared. It was as if Endler had found the brightness button for the fish’s colours, and he could turn it up and down at will.

In the streams of Trinidad, Guppies have nowhere to hide, and predation is an invincible force. The situation is different on coral reefs where the complex, rugged habitat allows fish to slip out of sight and conceal their colours. When predators are near, fish dash under a head of coral or into a small cave to hide. When the coast is clear they emerge and flaunt their colours, even positioning themselves in sunbeams to show off to mates and warn off intruders. And some reef fish spread out the pigment granules in their chromatophores, making their poster colours even brighter when they meet competitors. At night they dim their colours to reduce the chance they’ll be spotted while they rest on the seabed.

John Endler helped to make Guppies some of the most famous fish in the world, at least among biologists. In the last few decades, they’ve become a popular species for researchers who are trying to answer big questions about evolution and ecology.

Guppies now live in colonies in research labs worldwide and biologists still venture out to study them in the forested mountains of Trinidad. Every year more details of their lives come to light, and with them come new insights into how flexible and adaptable living things can be. In 2007, researchers at the University of Toronto saw that male Guppies have uneven patches of colour on either side of their body – their patterns are not symmetrical. While dancing for a female, trying to convince her to mate with him, a male will show her only his better, more colourful side.

A 2013 study in Trinidad revealed that female Guppies prefer odd-looking males with rare colours. But like a new fashion that starts among a few, edgy individuals – like hipster beards, lumberjack shirts or thick-rimmed spectacles – it soon catches on until almost everyone looks the same. Eventually those colours that once were rare and exciting among the Guppies become too popular and fall out of favour. Females probably evolved a preference for rare colours because it helps them avoid inbreeding and mating with close relatives. As an upshot, Guppy populations cycle through colours, keeping a mix of many tints and maintaining their reputation as ‘rainbowfish’.

Many other studies, in particular by David Reznick’s research lab at the University of California (Riverside), have shown that plenty of other Guppy attributes, besides colour, can quickly shift and change in the streams of Trinidad: their body size, their lifespan, the age they reach sexual maturity and the number and size of their offspring all respond rapidly to changes in predation.

Reznick’s team has measured the rate of Guppy evolution in terms of darwins (in 1949, British scientist J. B. S. Haldane proposed the darwin as a relative unit of evolution).9 In one study, Resnick found his Guppies were evolving a rate of between 3,700 to 45,000 darwins. The fastest rates measured in the fossil record are between 0.1 and 1 darwin. Some say it’s meaningless to compare the two time scales, of Guppies changing over a matter of months and ancient species evolving over many millions of years. But Reznick and others argue that the pathways of micro-evolution have a lot to tell us about the coming and going of species throughout the history of life on Earth.

Guppies in the wild are still considered to be a single species, for now at least. In other fish, studies are showing that factors like female colour choice can quickly set up barriers to mating, splitting populations and in time leading to the evolution of new species. And when those colourful barriers break down, species can be lost.

Mix all the colours and get brown

Until 30 years ago, 500 species of cichlid lived in the waters of Lake Victoria, one of Africa’s Great Lakes. Since then, however, around 70 per cent of them have gone extinct. The blame is often pinned on Nile Perch. These enormous predatory fish were introduced to the lake in the 1950s as a source of food. They can grow up to two meters (6.5ft) and have a big appetite for cichlids – but not for all of them. The perch ignore at least 200 cichlid species, yet many of them have disappeared nonetheless. There’s an additional explanation for the cichlids’ demise, one that’s only indirectly related to the predatory perch.

Like Guppies, female cichlids tend to prefer mates of certain colours, and it’s now widely accepted that this is the only thing keeping many cichlid species from interbreeding. There is a common misconception that distinct species are incapable of mating with each other and producing fertile offspring. Actually, different species can successfully breed together quite often, it’s just that they usually don’t because other things stop them, either physical barriers like a mountain range, or behaviours, such as females only mating with males of a certain colour. Lake Victoria’s cichlids evolved so rapidly, in perhaps as little as 12,500 years, that no other barriers to interbreeding have had a chance to arise – only colour choice. And over the last few decades, that single, vulnerable barrier has been dismantled as the lake’s waters have changed.

Back in the 1920s, if you’d gone for a swim in Lake Victoria, ducked your head underwater and opened your eyes you would have been able to see around five to eight metres (16–26ft) in front of you. If you did the same thing in the 1990s you might only have seen a metre (3ft) ahead. The lake’s waters have been getting murkier because fertilisers from farmland runoff are stimulating blooms of phytoplankton in the lake. Sediments have also poured in as surrounding forests were felled and roots loosened their grip on the soil, leading to erosion. And the reason the trees were cut down? To build fires for smoking all those introduced Nile Perch.

Studies in the lab and the wild, many led by Ole Seehausen, now at the University of Bern in Switzerland, have examined the effects of Lake Victoria’s cloudy water on its cichlid species. In aquarium tanks, when female cichlids are illuminated in monochromatic light (a good approximation for what’s happening in Lake Victoria), they can no longer distinguish between blue and red males of different species. In the gloom, the males’ colours look washed out and indistinct, in a similar way that red colours are lost the deeper underwater you go. Because the females can no longer tell who is who from their colours, they mate at random and the barrier to interbreeding comes down.

The same thing seems to be happening out in the wild. The parts of Lake Victoria with clearer waters are home to the most cichlid species, whose colours remain bright and distinct. In these areas females can still see the males’ colours and pick their own species to mate with. But the murkier the water, the more drab the fish and the fewer species present.10

Cichlids are in peril not simply because they’re hunted by introduced Nile Perch but because they’re having a hard time seeing each other’s colours. Gloomy waters are interfering with cichlid mating habits. Where the lights are dimmed, species are interbreeding, losing their vivid colours and collapsing in on each other. Unwittingly, humans are stealing away species, and at the same time making the world a less colourful place.

Ireland, traditional

There was once a well with nine magic hazelnut trees growing beside it, and if you peered in you might have glimpsed a large, gleaming salmon circling in the water below. One day, each of the trees dropped a nut into the well, and when the salmon ate them it gained all the knowledge in the world. A prophecy said that the great poet, Finegas, would catch that salmon and eat it, and then he would know all there was to know.

For seven years Finegas sat beside the well with his fishing rod and tried to hook the salmon. When finally he did, he asked his apprentice, Fionn MacCool, to cook it for him. ‘But whatever you do,’ Finegas warned, ‘do not eat the salmon.’ Fionn did as he was told and carefully prepared the fish, roasting it over a peat fire. But as he reached in to turn the cooking salmon, a drop of hot oil spattered onto Fionn’s hand. With a jolt of pain, the boy stuck his burnt thumb in his mouth to soothe and cool it.

When Finegas saw Fionn, he noticed a new fire shining in his eyes. ‘Did you eat the salmon?’ he demanded. Fionn pleaded that he hadn’t, but he told him how the sizzling hot oil had landed on him. Then Finegas knew what had happened. All the salmon’s knowledge had passed to Fionn. From then on, Fionn could call upon all there was to know in the world simply by sucking his thumb, and he became a great warrior and leader of the Fianna, a famous band of roaming Irish heroes.

Notes

1 As part of Barack Obama’s legacy, he expanded the Papahānaumokuākea Marine National Monument in the central Pacific, protecting 1.5 million square kilometres (580,000 square miles) of ocean waters, including many coral reefs and the home range of the critically endangered Hawaiian Monk Seal.

2 Morphs are variations of the same species within a population that somehow appear different, in size or colour, for example. Often it’s males and females that differ from each other, with this phenomenon known as sexual dimorphism.

3 Ambon Damselfish were named in 1868 by the Dutch ichthyologist Pieter Bleeker, a decade after Alfred Wallace was in Ambon; the species ranges across the Western Pacific from Japan to Australia.

4 It’s likely that other blue pigments will eventually be found in other living things. Blue-skinned poison-arrow frogs are candidates, but no one has yet been brave enough to check.

5 In 2007, a copy sold at auction in London for £43,200.

6 Known by his middle name, Lechmere. Robert Lechmere Guppy.

7 The Guppy’s scientific name has shifted over the years, with various synonyms rejected in favour of Poecilia reticulata.

8 Female Guppies produce their first offspring at the age of 10–20 weeks; males mature after seven weeks or less. Unusually for teleosts, Guppies mate with each other: the male inserts sperm into the female with a modified anal fin, the gonopodium, and she gives birth to live young.

9 One darwin is defined as the change in a particular trait by a factor of e in one million years, where e = 2.718 (or thereabouts).

10 Researchers are also finding more hybrid fish, the results of this interbreeding.